Chapter 2

POP ICONS

Tribute to Dick Clark

Dick Clark inspired widespread nostalgia and cultural interaction in our culture. Those of us who have known and worked with him will never forget his humor, his sense of fairness, his encouraging ways, the optimistic disposition, the gut instinct and the lasting impacts that he made on our later successes.

I started out my career by aspiring to be like Dick Clark. Thanks to great mentors, I learned to be my own best self, a visionary thinker and a repository of great case studies. I appeared on radio and TV with him, as well as on conference stages. It was he who encouraged your own leadership qualities, because your success ultimately honored him.

Dick Clark grew up working in a radio station in Utica, NY, perfecting the talk and the interest in music. He realized that music styles changed rapidly and that their cultural impact affected. When opportunity came calling, he was ready, willing and able. He replaced other DJ’s as host of a local bandstand show at WFILTV in Philadelphia, PA, switching his musical emphasis from big bands and easy listening music to the emerging rock n’ roll. His bandstand show was a runaway hit and quickly was picked up by the ABC-TV network as a daily after-school show aimed at teens.

The success of “American Bandstand” spawned a weekly TV music variety series from New York, “The Dick Clark Beechnut Show,” which in turn inspired concert tours, “The Dick Clark Caravan of Stars.” He appeared in movies, as a teacher in “Because They’re Young” and a doctor in “The Young Doctors.” He was clean cut, respectful and mannerly, thus bringing legitimacy to rock n’ roll. With the celebrity, he was hired to guest-star as an actor in TV shows such as “Stoney Burke,” “Adam-12,” “Honey West,” “Branded,” “Ben Casey,” “Coronet Blue” and “Burke’s Law.” He played the last villain on the last episode of the “Perry Mason” weekly TV series.

The 1963 move from Philadelphia to Hollywood, CA, launched Dick Clark Productions. Though “American Bandstand” was owned by the network, he mounted what became a 50-year span of programs that he owned, produced and nurtured, including “The People’s Choice Awards,” “Where the Action Is,” “Live Wednesday,” “American Dreams,” “The Happening,” “New Year’s Rocking Eve,” “Academy of Country Music Awards,” “Super Bloopers and Practical Jokes,” “American Music Awards,” specials, TV movies, game shows and more.

To go to his office and have meetings was like being in a museum. You sat at his desk in antique barber chairs, wrote on roll-top desks and enjoyed furnishings from nostalgic shops. Big band music played from a Wurlitzer juke box, and classic cars adorned the parking lot.

These are some of the principles that I developed myself but credit being inspired by Dick Clark. I’ve taught them to others and shared with him as well:

Dick Clark liked to celebrate the successes of others. I’ve found that reciting precedents of successful strategy tends to inspire others to re-examine their own. Here are some other lessons that he taught us:

I’ll close this tribute to Dick Clark with some of the songs from American Bandstand that have applicability to business strategy:

Nourishing a Definitive Body of Work Through the Burt Bacharach Songbook.

Just as companies have books of business and corporate cultures, so do individuals, who in turn populate and influence organizations. This section looks through the prism of music and salutes the famed composer Burt Bacharach as the analogy for a fine, rich and definitive Body of Work.

At the beginning of my career, I was a radio DJ. I started in 1958, a golden period for music. Because Payola was looming as an issue in our industry, we were required to keep logs of the songs that were played, containing the labels on which they appeared, the names of the composers and other information. In today’s industry, that would all be on spreadsheets. However, the manual writing of spreadsheets gave us the chance to digest and learn from the information, developing the skills to better program for our audience. To this day, I can look at the label of a record and, judging by the serial number, can tell you its date of release.

A bunch of records were in the Top 40 at that time: “Magic Moments” by Perry Como, “Story of My Life” by Marty Robbins, “The Blob” by the Five Blobs, “Another Time Another Place” by Patti Page and “Hot Spell” by Margaret Whiting. I zeroed into the fact that the music composer of all these diverse hits was Burt Bacharach, though the lyricists were different names.

It occurred to me that this was a talent to watch, as I was already familiar with established composers such as George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin and others. I sensed early-on that Bacharach would belong in that upper echelon on Tin Pan Alley icons. Concurrently, I became familiar with the work of other young emerging music composers, such as Carole King, Buddy Holly, Paul Anka, Barry Mann, Neil Sedaka, John Lennon and Paul McCartney.

Throughout the 1960s, the music of Burt Bacharach and lyricist Hal David was everywhere. In the rock era, there were still hits and radio airplay for easy listening music, ballads, movie title songs and the like. The playlists were balanced and gave the public a full array of musical styles.

One could spot a Bacharach tune because it had a definable style. Bacharach himself played piano on and conducted many of the important hits. His arrangements fit the performers and needs of each piece. Yet, the hits had identifiable traits of a Bacharach production. Many talented artists wanted to record his songs, with his arrangements. The public sought out recordings with his hits. All of that represents Body of Work for a composer. Through the 1960s and 1970s, Bacharach broadened and experimented in creative directions. There was a Broadway show, a TV musical revue, movie soundtracks and movie tie-in tunes. He hosted TV specials and performed concerts of his music.

In the decades of the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s, newer fans and younger generations kept discovering Burt Bacharach. His old songs spoke to them, were updated and re-recorded. He collaborated with other musical talents (Elvis Costello, Carole Bayer Sager and James Ingram). Every decade, he kept getting rediscovered and re-recorded. There were tribute concerts and retrospectives. The Body of Work stood the test of time and appealed to wider audiences.

With the renewed interest in Burt Bacharach came the reissues of recordings. With the popularity of CDs came the retrospectives of his early work. Being a Bacharach fan, I acquired the compilations and fell in love with a whole new earlier Body of Work.

There were songs that I had played on the radio but had not realized that they were by Burt Bacharach. These included “You’re Following Me” by Perry Como, “Be True to Yourself” by Bobby Vee, “Keep Me in Mind” by Patti Page, “Heavenly” by Johnny Mathis, “Take Me to Your Ladder” by Buddy Clinton, “Along Came Joe” by Merv Griffin, “Mexican Divorce” by The Drifters, “The Night That Heaven Fell” by Tony Bennett, “Blue on Blue” by Bobby Vinton and “Don’t You Believe It” by Andy Williams.

I started discovering all those songs from Bacharach’s early Body of Work that I had never heard before. As a Bacharach fan since 1958, I found myself in the same company as the younger music fans who have discovered his work and found relevance to their contemporary lives. My own personal favorites from these compilations (highly recommended that you hear, buy and download) include:

What I found in these musical gems was magical. Many of those songs stood on their own merits, serving the needs of the performers at the time. They served as building blocks for what became the definitive Bacharach sound.

That is the way that I am with business wisdom. I continually dust off old chestnuts and reapply them for clients, in my books, through my speeches and in sharing with mentees. The case studies become the substance of what we provide future clients. We benefit from going back and learning from our own early Body of Work, assuming that we strategized our career to be a long-term thing, as Burt Bacharach did. Everything we are in business stems from what we’ve been taught or not taught to date. A career is all about devoting resources to amplifying talents and abilities, with relevancy toward a viable end result. Failure to prepare for the future spells certain death for businesses and industries in which they function.

I’ll close by adding business analogies to some Burt Bacharach song hits:

A rich and sustaining Body of Work results from a greater business commitment and heightened self-awareness. None of us can escape those pervasive influences that have affected our lives, including music and the messages contained in songs. Like sponges, we absorbed the information, giving us views of life that have helped mold our business and personal relationships.

Lessons from The Monkees Apply to Success

It was the night of February 9, 1964. Davy Jones stood backstage at the Ed Sullivan Theatre in New York City. As a teenage actor and singer, he was in the cast of the Broadway hit “Oliver,” starring British singer Georgia Brown. That was the night that The Beatles invaded America, starring on CBS-TV’s “Ed Sullivan Show.” There were other acts on the bill that night, including comedian Frank Gorshin, singer Tessie O’Shea, the comedy team of Charlie Brill & Mitzi McCall and the “Oliver” cast to perform scenes from the show for the TV audience.

Jones watched the Beatles perform in their American television debut and mused that he would like to get a gig like that one day. He in fact did two and a half years later, as a cast member in a TV sitcom that was inspired by The Beatles’ movie “Hard Day’s Night.”

Hollywood responded to Beatlemania by putting together a group of actors to play a Beatles type teenage pop group. “The Monkees” was primarily a TV sitcom, and it was produced by Columbia-Screen Gems, whose other hits included “Bewitched,” “I Dream of Jeannie,” “Gidget” and “The Flying Nun.” Stars Michael Nesmith and Davy Jones had music in their repertoire. Mickey Dolenz and Peter Tork were actors who portrayed pop musicians.

The songs were written by Tommy Boyce, Bobby Hart, Neil Diamond, Carole King, John Stewart and other top talents. The recordings featured studio musicians. The Monkees tended to the sitcom and lip-synced two songs per episode, one of them done in a new, original format: as a music video.

Once The Monkees debuted on NBC-TV, they were an instant hit. They primed the pre-teen market for such later luminaries as Herman’s Hermits, Paul Revere & the Raiders, The Cowsills and The Partridge Family. The TV show spawned concert tours, and The Monkees had to learn to play instruments. There were guest shots, product tie-in’s, merchandising and Monkees fan clubs. All this activity jelled with The Monkees, and it became the prototype for other pop acts packaged as big business.

Arguably, music videos were invented as theatrical shorts. Staging pop hits was popularized in the 1950s by NBC-TV’s “Your Hit Parade.” Variety shows such as Sullivan’s brought the top recording acts to TV audiences. But it was The Monkees who set the prototype for music videos, which MTV later patterned its format.

Monkee Michael Nesmith not only was the creative juice behind music videos, but his mother was another trailblazer in the business world. As a secretary in Dallas, Texas, she invented the office product Liquid Paper.

Critics said that The Monkees were cute mop-tops (with Davy Jones being the cutest). They were lambasted for not playing their own music. As the group took control of their instruments on stage, they began receiving respect as legitimate musicians. Their success helped to fund charitable causes.

The Monkees lasted only two seasons on NBC-TV. There was “Head,” the Monkees movie. There were recordings and concert tours that outlasted the series. Monkee members Nesmith and Jones had solo careers. Periodically, The Monkees would reunite for nostalgia tours.

There are four basic kinds of companies:

Collaborations, Partnering and Joint Venturing (discussed in Chapter 8 of my book, The Business Tree™). The Monkees led to “Michael Nesmith’s Elephant Parts,” which led to MTV music videos. Many TV shows (comedies and dramas) have since incorporated music video inserts. Monkees money helped bankroll Woodstock and music videos by other artists.

The Monkees were that rare business enterprise that applied to all four categories of business. Then there is the dynamic of casting the right actors to play the right parts. Most musical groups came together by happenstance, many playing good music but not possessing charm and charisma. Alas, The Monkees as a study on better ways to conduct business.

I end with words of wisdom from the masters:

And some other golden oldies lyrics, for good measure:

Remembering Great Mentors

One never forgets their first mentor. I have had several great ones, who in turn taught me the value of passing it on to others. That’s why I advise businesses, write books, speak at conferences and more.

That first great mentor sticks with you always. Mine was legendary humorist and media figure Cactus Pryor. I started working for him in 1958, at KTBC Radio in Austin, TX. Cactus was the program director and morning radio personality. His show, filled with humor, humanity and music, was the natural lead-in to “Arthur Godfrey Time,” which we carried from the CBS Radio Network.

Cactus was 34 at the time that he began mentoring me. He had grown up around show business. His father, Skinny Pryor, owned a movie theatre and entertained audiences with comedy routines during intermissions. Cactus was inspired by all that he saw. He joined KTBC as a disc jockey in 1945, becoming program director. When the station signed on its TV station on Thanksgiving Day, 1952, Cactus was the first personality on the screen. He welcomed viewers and introduced the first two programs, the University of Texas vs. Texas A&M football game, followed by the “Howdy Doody Show” from the NBC-TV Network.

Cactus had been doing his morning show from his home, with his kids as regulars, with the repartee being similar to Art Linkletter interviewing children. Early in 1958, he was doing his morning show back in the studio. I started as his regular on Saturday mornings, and he gave me segments to do. From him, I learned valuable lessons. You cannot be a carbon copy of everyone else. He wanted me to like and respect Dick Clark but not become a clone of him. Being one of a kind is a long quest. He wanted me to set my own tone and not be labeled by others.

From Cactus Pryor and a 24-year old newscaster named Bill Moyers, I learned that if you take the dirtiest job and do it better than everyone else, you will become a solid expert. In the good old days of regulated broadcasting, stations had to keep logs of the music, to avoid the hint of Payola (a growing controversy at the time). I kept the logs and learned about the music, the record companies, the composers and much more.

Stations also had to perform Community Ascertainment by going into the community, inquiring about issues, and assuring that broadcasting addressed those issues. That’s where I learned to file license renewals. That’s where I learned the value of public service announcements and public affairs program, which deregulation precluded broadcasting from doing. From that mentoring, I fell in love with the non-profit culture, the organizations and the client bases affected by them. Community Ascertainment inspired me to the lifelong championing of not-forprofit groups and their fine works. From that experience, I still advise corporations to set up non-profit foundations and do good deeds.

The early days of television were creative. Cactus hosted a local variety show on Channel 7. He interviewed interesting locals, showcased local talent and did comedy material. One of his advertisers was an appliance store and, while showing the latest TV sets, Cactus kicked their screens to demonstrate their rugged qualities. When the station left its first temporary home at the transmitter atop Mount Larson, Cactus was carried out in the chair in which he was sitting, a symbol that the variety show would move to the new studio at the corner of 6th and Brazos.

Cactus began developing special characters, with unique personas. That first year in which I worked with him, he created a puppet, Theopolous P. Duck. It was inspired by Edgar Bergen’s characters. Mr. Duck delivered jokes with a cultured accent. He appeared in comedy spoof segments on local KTBC-TV shows, such as “Now Dig This” (hosted by Ricci Ware), “Woman’s World” (hosted by Jean Covert Boone) and the “Uncle Jay Show” (hosted by Jay Hodgson).

During that time, he developed a famous sign-off phrase. Network stars had their own, such Garry Moore’s “Be very kind to each other.” Cactus used the phrase: “Thanks a lot. Lots of luck. And thermostrockamortimer.” He joked that his made-up term meant “go to hell.” But really, he wanted to tantalize people into thinking bigger thoughts and being their best.

Cactus loved to play on words, giving twists to keep the listeners alert. He used turns of phrases such as “capital entertainment for the capitol city” and “that solid sound in Austin town.” In talking breaks for our sister station (KRGV), he said “that solid sound in the valley round.”

He taught me how to deliver live commercials and to ad-lib. In those days, we would do live remotes for advertisers, inviting people to come out, get prizes and meet us at the external location. Doing such remotes got us appearance fees, and they really drew for the advertisers.

Through the remotes, I learned how to feed lines and develop the talent to speak in sound bites, as I do for business media interviews to this day. I was with Cactus at a remote for Armstrong-Johnson Ford. The out-cue was to describe the 1959 Ford model. Cactus said, “It’s sleek and dazzling, from its car-front to its car-rear.” That was a cue for the studio DJ to play a commercial for the Career Shop, a clothing retailer. Today, when I use nouns as verbs and place business terms out of context to make people think creatively, I’m thinking back to Cactus Pryor.

One remote on which I joined Cactus was for the fourth KFC franchise in the United States. We got to interview Colonel Harland Sanders on his new business venture. Little did I know that, 20 years later, KFC would be a corporate client of mine, and I would be advising them how to vision forward, following the Colonel’s death.

Music programming was important to Cactus Pryor and, thus, to me. Mentees of his understood and advocated broad musical playlists, with the variety to appeal broadly. Under a “service radio” format, different day-parts showcased different musical genres. He believed that virtually any record could be played, within context. One of the programming tricks that I taught him was to commemorate Bing Crosby’s birthday each May by playing “White Christmas” and other holiday hits out of season, which got the listeners fascinated.

In those days, you could play rock n’ roll hits from the KTBC Pop Poll, a list that was circulated to local record stars as a cross-promotion. There were also positions in the “clock” devoted to easy listening artists, instrumentals, country cross-overs and what Cactus called “another KTBC golden disc, time tested for your pleasure.”

Cactus liked rock n’ roll but wanted to see that easy listening records got proper attention. He would indicate his interest in notes on the green shucks that encased the records. As a write this section, I’m holding “Many a Time,” a 1958 release by Steve Lawrence, an easy-listening star who was beginning to also be considered a teen idol. Here’s the dialog from this record jacket: “Plug hard as hell. Experiment to see if we can get it on the Pop Poll. Cactus.” One of the DJ’s wrote, “How hard is hell?” Cactus wrote a reply, “Hard, ain’t it hard.” Steve Lawrence would subsequently have many teen hits (“Pretty Blue Eyes,” “Portrait of My Love,” “Go Away Little Girl,” “Walking Proud.” etc.).

Humor was the beacon over everything that he did. Cactus began recording comedy records, such as “Point of Order” on the Four Star Label and still others for Austin-based Trinity Records. He began writing a humorous newspaper column, “Cacti’s Comments.”

Besides his radio work, Cactus Pryor got bookings as an after-dinner speaker. In the early years, he gave comedy monologues and historical narratives. Always lively and entertaining, he inspired audiences to think the bigger ideas and look beyond the obvious. I follow his tenets in delivering business keynotes and facilitating think tanks and corporate retreats.

His gigs got more humorous. Cactus created different personas, replete with costume and makeup. His first was a European diplomat who had the same voice and inflection as Theopolous P. Duck. He would deliver funny zingers, often touching upon political sacred cows. Then, he would peel off the mustache and ask, “Ain’t it tacky?” He would then divulge that he actually was humorist Cactus Pryor from Austin, Texas. The act was well accepted and perfected during the era when our boss, Lyndon B. Johnson, was President of the United States.

Cactus did national TV variety shows. He was the “other Richard Pryor.” He continued developing characters and entertaining audiences up through the 1990’s, when his son Paul had begun doing the circuit as well. Paul is a funny satirist as well, something that I had known back when he was a school buddy of my sister Julie.

John Wayne called Cactus “one of the funniest guys around” and invited him to appear in two classic Wayne movies, “The Green Berets” and “The Hellfighters.” I recall visiting Cactus on the set of “The Green Berets” in Benning, Georgia, and seeing him keep stars John Wayne, David Janssen, Jim Hutton and Bruce Cabot in stitches in between shots and poker games.

Though national fame beckoned, he kept his roots in Austin, claiming, “There is no way to follow laughs onstage but with pancakes at City Park.” He stayed in his beloved Centex community. He did write books on Texana and history. There were contributions to the news-talk stations.

These are some lasting things that I learned from my first mentor (Cactus Pryor), and I’ve shared them with corporations and audiences all over this world:

And these are some of the insights that I have developed, inspired by his early mentoring:

I met Steven Spielberg in 1970 at the beginning of his film directing career. I was at Universal Studios, interviewing Robert Young on his TV series “Marcus Welby, M.D.” Young felt that his young TV episode director (Spielberg) would be one of the superstars of Hollywood, and he was right. Spielberg had this distinguished five-year career, directing three made-for-TV movies and episodes of shows like “Columbo,” “The Bold Ones,” Rod Serling’s Night Gallery” and “Name of the Game.” This prepared him for a dynamic movie career. What we do in our salad days sets the tone for magnificent career achievements.

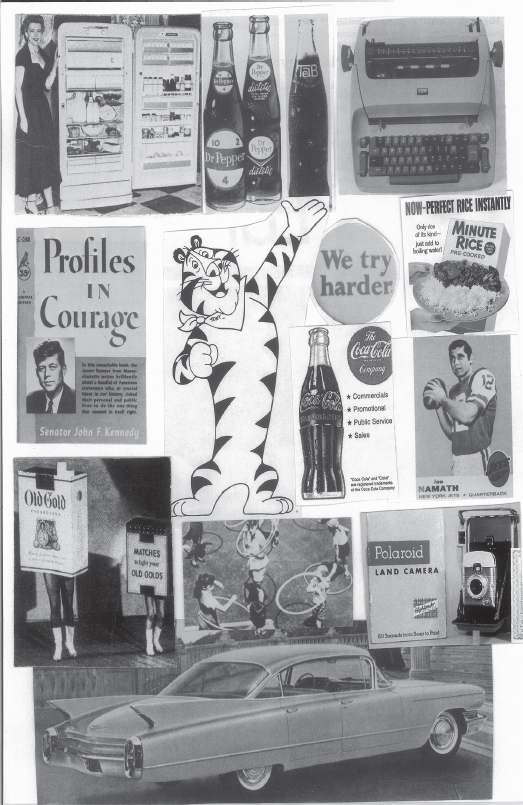

Pop Icons Collage.

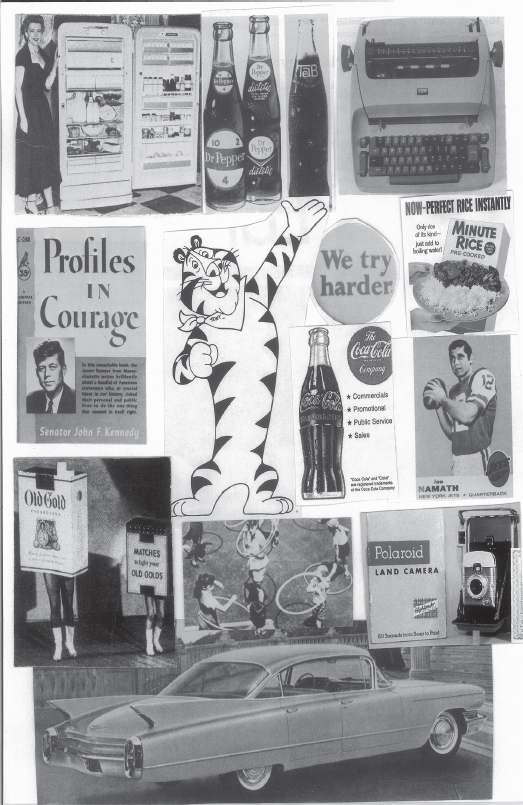

Author Hank Moore is pictured with Dick Clark. Photo taken in 1976.

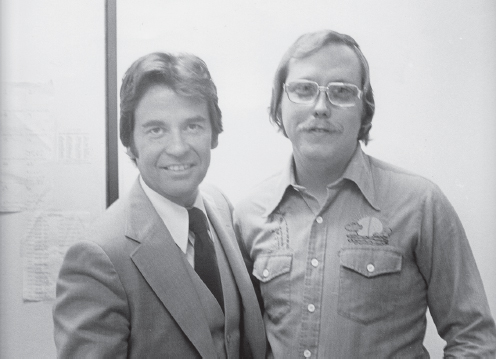

Author Hank Moore is pictured with Sonny and Cher. Photo taken in 1967.