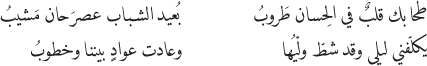

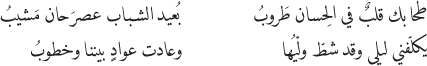

ṭaḥā bika qalbun fī l-ḥisāni ṭarūbū |

bu‘ayda sh-shabābi ‘aṣra ḥāna mashībū |

yukallifunī laylā wa-qad shaṭṭa walyuhā |

wa-‘ādat ‘awādin baynanā wa-khuṭūbū8 |

Meter (al-ṭawīl): SLX SLLL SLX SLSL / SLX SLLL SLS SLL; the second/sixth foot is occasionally SLSL (e.g. in line 1b), which only occurs in older poetry. Ṭawīl is the most common meter in all periods of classical Arabic verse. The rhyme is -ī/ūbū (in rhyme, ī and ū are interchangeable immediately before the rhyme consonant, but not following it).

This and the next two poems from the mid-sixth century are taken from an ancient and highly valued anthology of 126 pre-Islamic and early Islamic poems, called al-Mufaḍḍaliyyāt after the compiler, the philologist al-Mufaḍḍal al-Ḍabbī of Kufa (d. after 163/780). It is said that the anthology was composed at the request of the Abbasid caliph al-Manṣūr, the founder of Baghdad, for his son, the future caliph al-Mahdī. ‘Alqamah’s famous poem was composed on the occasion of the Battle of ‘Ayn Ubāgh which took place in AD 554 pitting the Ghassānid king, al-Ḥārith al-A‘raj, against the Lakhmid king, al-Mundhir ibn Mā’ al-Samā’ of al-Ḥīrah.

The poem opens with nasīb, or amatory introduction (1–10). Whatever the real origins of the nasīb, Arab critics explained that its function in an ode addressed to a patron was to put him in a favorable mood. As Shakespeare writes, in Love’s Labour Lost (IV, iii): “Never durst poet touch a pen to write / Until his ink were tempered with Love’s sighs; / O! then his lines would ravish savage ears, / And plant in tyrants mild humility.”9

Then the poem turns to a description of the camel (11–21) that brings the poet to the court of al-Ḥārith; this is followed by a depiction of the battle (24–35), and closes with an appeal to al-Ḥārith to free the poet’s brother, taken prisoner at the battle (36–38). The petition was successful.

A heart by pretty girls enraptured carries you away;

long gone, though, is your youth; gray hairs appear.10

Laylā is on my mind, though she be far from me,

and obstacles, grave matters, are between us two.

She lives a life of luxury; one cannot speak to her:

a guard stands at the door to bar all visitors.

Her spouse’s secrets she does not divulge, when he’s away;

she makes his homecoming a pleasure for her spouse.

Do not equate me then, girl, with a callow youth—

5

may rain-filled clouds pour down their loads on you!

May southern, towering, low-lying clouds rain down

for you, borne by an evening south wind!

—But why should you be thinking of her, that Rabī‘ah girl,

for whom a well is being dug in Tharmadā’?11

You ask me about women? I’m a specialist,

an expert, knowing women’s ailments all!12

When a man’s hair turns gray, or when his wealth is scarce,

he has no share of tenderness from them.

What women want is wealth, wherever they know it is;

10

to them the bloom of youth is wonderful.

So leave her, and dispel your worries with a sturdy mount,13

like your desires and aims, which with two riders14 trots apace.

Toward al-Ḥārith the Munificent I made

my camel walk; her chest and end-ribs throbbing.

She’s fast; her flanks’ and shoulders’ flesh has been

consumed by midday heat and tireless pressing on.

I brought her to a well of brackish water, with

the taste of henna and ṣabīb.15

At dawn, after the nighttime journey, she looks like

15

a strong, young oryx with striped legs, fearing the hunter’s pack;16

(Amidst the arṭā trees men lurked, lying in wait for her;17

she dodged their arrows, and their dogs)

That she might take me to a man’s abode who once was far,

but now my nearing brought me near to your munificence.18

To you—may you be safe from curses19—was her course,

through frightful, fearsome lands that looked alike.

The lodestars20 led me, and a pathway plain to see,

with stones as marks upon the rocky ground.

20

There, corpses lie, abandoned beasts, their bones

bleached, and their hides dried hard.

She’s left to drink the cisterns’ dung-fouled dregs;

loathe it she may, but pasture fresh is a distant ride away.

Do not withhold favor from me, a foreigner:

I am a man who is a stranger in pavilions like yours.

You are a man in whom I put my trust.

Before you, lords have lorded over me and I was lost.

The Banū Ka‘b ibn ‘Awf brought home their lord;

another lord was left amidst his legions there.

25

By God! But for that knight of theirs on the black horse

they would have reached their homes—sweet home!—in shame.21

You drive him on until his fetlocks’ white turns red with blood;

you smite the helmets of the chainmailed men;

Wearing two hauberks over one another, carrying

two noble swords, “Clean Cutter,” “Sinker-in.”22

You fought them till they sought protection by their champion;

the sun was ready then to set.

The chainmail on their bodies rustled like

the rustling of dry cornfields when the wind is southerly.

30

Ghassān’s defenders battled there,

while Hinb and Qās stood firm, together with Shabīb.23

The man of Aws, and those that had been mustered by

‘Atīb and Jall, stood ready at his horse’s breast.

The camel calf above them in the sky roared loud.24

Some, dying, twitched their legs, still armored; some were stripped.

It was as if a cloud had hit them with its thunderbolts,

that made the birds crawl on the ground.

No one escaped, except a tall mare with its bridle, or a

lively stallion, a thoroughbred, slim like a lance,

Or else a warrior who guards his own, dyed red

35

by what had dripped from his sword’s edge.

You are the one who left his mark upon his foe,

the scars of a bad beating but of bounty too.

On every tribe you have conferred a benefit:

so Sha’s, too, is entitled to a bucketful of boon.

Al-Ḥārith has no peer among the people, none comes near,

except his prisoner; not even a kinsman comes as close.