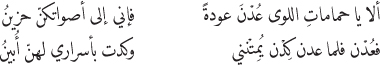

’alā yā ḥamāmāti l-liwā ‘udna ‘awdatan |

fa-’innī ’ilā ’aṣwātikunna ḥazīnū |

fa-‘udna fa-lammā ‘udna kidna yumitnanī |

wa-kidtu bi-’asrārī lahunna ’ubīnū117 |

Meter (al-ṭawīl): SLX SLLL SLX SLSL / SLX SLLL SLS SLL; rhyme: -ī/ūnū.

The poet is unknown, but versions or lines of the poem are attributed to the semi-legendary Majnūn Laylā (see below), to Jamīl (d. 82/701), and to Ibn al-Dumaynah (second/eighth century).

These lines served as a song text (indicated by the heading ṣawt, literally “voice”) for at least two famous early Abbasid singers, and may be considered an independent poem even though these lines can be found as part of longer pieces too. About the music we know virtually nothing (Muḥammad ibn al-Ḥārith sang these lyrics in khafīf al-ramal rhythm, a kind of triple measure, “with the middle finger,” referring to a particular scale or mode on the lute). The general term for “love poetry” is ghazal; in later times, in Persian, it comes to mean “short love poem.” It is distinguished (but not always too clearly) from the elegiac nasīb that serves as introduction to qaṣīdahs.

The large work from which this song text is taken, Kitāb al-Aghānī (The Book of Songs) is an extremely important source for our knowledge of Arabic poetry, poets, and singers. Its author, Abū l-Faraj al-Iṣfahānī (d. ca. 363/972), took as his starting point a collection of famous song lyrics. They are almost always very short, a handful of lines: it is sometimes incorrectly assumed that long poems were regularly sung.118

Like countless other Arabic poems, this piece is about lost love and memory and clearly part of the ‘Udhrite tradition (after the tribe of ‘Udhrah, who had a reputation for their chaste and self-effacing love for an unattainable woman; see the story of Qays and Lubnā in this volume, translated from al-Aghānī). Al-Liwā is either a place name or a description of a place (“the twisted sand dune”) where the poet-lover presumably once met his absent beloved. Doves, in Arabic poetry and lore, are supposed to be perpetually lamenting the loss of a young pigeon who was killed after leaving Noah’s ark (this dove chick was called al-Hadīl; hadīl, mentioned in a variant, also means the cooing sound of pigeons). When the poet says in the last line that he cries for them, he means that he cries for their loss as well as his own. The basic structure: line 1: apostrophe (the quotation marks in the translation are the equivalent of the implicit “I said:”; lines 2–4: “narrative” sequence describing the result of the apostrophe, with line 4 serving as general statement by way of conclusion, which seems to look back on the events described in 2–3. There are therefore three temporal levels implied in this otherwise not very remarkable poem—but note the level of sounds, such as the repetition of n and m: a suitable text for singing.

“O doves of al-Liwā, turn back again!

I sadly long to hear your voices.”

So they turned back, but when they did I nearly died

and I almost revealed my hidden feelings.

They called, repeating their sounds as if

they had been given wine to drink, or were possessed.

Whenever my eyes saw doves like them,

crying, these eyes would shed tears for them.