Fig. 1

Tactics before Shaka

Traditional giya formation

It remains true today that the origins of the Bantu tribe, from the ancient abaNtu, are unknown, but reasoned supposition suggests that they entered Africa from the Middle East as long ago as 8,000 BC. As their lives were always centred on cattle, they led a nomadic life and in due course spread south and then laterally across central Africa, eventually reaching the west coast. They then retraced their route and progressed south-east around the wastes of the Kalahari Desert; one Bantu tribe, the Nguni, settled extensively in the area known today as Natal, probably between 1500 and 1700 AD. This left the bulk of the Bantu, the predominately Xhosa tribe, steadily moving south while, unknowingly and only 500 miles away, the Boers were busy founding their first colony in the area known today as Cape Town. It is ironic that a migration of such magnitude should have failed to reach the Cape and that Europeans should fill that vacuum at exactly the same point in time.

By the end of the seventeenth century the Nguni tribe probably amounted to no more than three or four thousand people living under the vague and aged chieftaincy of Jobe. An insignificant and little known fringe group of between one and two hundred people lived near the coast on the banks of the White Mfolozi River. Their chief, Malandela, had a son named Zulu, meaning ‘of heaven’, who eventually succeeded him and under whose chieftaincy the small group thrived. Two brothers followed him, Mageba and Punga, who then gave way to Senzangakona at the time the Xhosa first came into conflict with the Boers at the Great Fish River. During this embryonic stage of their development, the group adopted the title ‘Zulu’ and had grown in size to well over one thousand. Senzangakona had many wives but, not being satisfied with them, secretly dallied with the daughter of a neighbouring eLangeni chief. Marriage to the unfortunate pregnant girl, Nandi, was impossible because she was not a Zulu.

After Nandi gave birth to a son, the eLangeni banished the disgraced Nandi and her child, which morally forced Senzangakona to appoint Nandi as his unofficial third wife, and she was readmitted to her tribe. Senzangakona refused to recognise his son so, in defiance, Nandi named him Shaka after a common intestinal beetle.

By 1802, the eLangeni could no longer tolerate Nandi and her family and banished them into destitution at a time when the whole land was suffering widespread famine. Nandi fled to the Qwabe clan, where she had once given birth to a son by a Qwabe warrior named Gendeyana. Under Gendeyana's guidance, Shaka developed into such an excellent warrior that Senzangakona sought the return of this fine young combatant – whether to develop his skills or to murder him is unclear. Nandi's suspicions led her to move her family to yet another clan in order to protect Shaka from his father. Shaka's reputation increased, and legend records both his fearlessness when hunting wild animals and his great prowess with the spear. At the age of twenty-four, Shaka was called to join King Dingiswayo's regiment of ‘national service’ warriors. During the next five years he closely studied the king's strategy of establishing control over other tribes by the use of brutal and aggressive tactics, a policy frequently but incorrectly attributed first to Shaka.

Under Dingiswayo, Shaka rose through the ranks until he led the IziCwa regiment, and it was here that he taught his warriors the close combat for which they became famous. As proof of his stamina and fitness Shaka always went barefoot, considering sandals to be an impediment. He ordered the ineffective throwing spears to be melted down and recast as the long, sharp, flat-bladed assegai or ikwa – the onomatopoeic term taken from the sucking sound of the blade being withdrawn from a body. Shaka was frustrated with conventional spears which when thrown were lost to the enemy, or when used during close combat tended to snap at the shaft. He ordered his regiment's traditional weighty shields to be cut down and made stronger, so that in close combat the new shield could be hooked under that of an opponent and when twisted sideways would expose the opponent's body to the deadly ikwa thrust.

Shaka was in his early thirties when his ruthless reign began. Opponents and dissenters were mercilessly executed, as were warriors who did not reach the exacting physical standards required for a Zulu impi, the fighting unit, usually of regimental strength. Shaka embraced all the techniques he had learnt during his years with the IziCwa: he perfected the ikwa stabbing spear and developed the impondo zankhomo (see Fig. 2 on p. 23), the feared encircling technique known as the‘horns of the buffalo’, whereby an enemy was encircled by the fast running flanks of each horn until completely surrounded. The main Zulu body would then engage and slaughter the surrounded enemy, using the close-combat techniques of shield and stabbing assegai. Shaka drilled his Zulus remorselessly until he had a highly trained impi numbering no more than three hundred warriors. The first major test of this small regiment was a confrontation with his neighbours, the belligerent Buthelezi clan. Shaka ordered his regiment to advance with their shields ‘edge on’ to give the illusion of minimal numbers. His ‘horns’ rapidly encircled the Buthelezi, whose vocal dependants were watching from a nearby hillside. Shaka then gave the order for shields to be turned to face the deceived Buthelezi, revealing the true numbers of his men. His disciplined regiment drove into the terrified Buthelezi warriors, quickly slaughtering them before the distraught onlookers.

By 1818 Shaka's impi had grown to more than two thousand warriors, and his sphere of influence was steadily increasing while other Bantu tribes engaged in totally destructive warfare against each other.

In early 1824 an event occurred which was to bring radical change to the Zulus. Shaka had heard of the handful of white men living at Port Natal, and to satisfy his curiosity sent them an invitation to visit his kraal at kwaBulawayo (the place of he who kills). The visiting party consisted of Lieutenant Francis Farewell RN, Henry Fynn, the British resident in Zululand, four hardy pioneers, John Cane, Henry Ogle, Joseph Powell and Thomas Halstead, and they carried a large number of gifts. The party arrived in July and was awed by the size of the royal homestead. It measured at least three miles in circumference and housed the royal huts, the royal cattle pen containing seven thousand pure white cattle, and two thousand domestic huts. Shaka, who was protected by twelve thousand of his best warriors, greeted the party. After various displays and feasts, Farewell and Fynn finally met Shaka, and during one of their meetings they sought and were granted trading rights for the Farewell Trading Company. The party returned to Port Natal, but without Fynn who remained at Shaka's request – not as a hostage, but to enable Shaka to learn more of the white men. Fynn was residing at the royal kraal when an attempt was made on Shaka's life. He was stabbed through the left arm and ribs by an unknown assailant and lay at death's door for a week. During this time, Fynn cleaned and bandaged the wound and generally watched over Shaka, who quickly recovered. Shaka believed that members of the distant Qwabe tribe had made the attempt; accordingly, two impis were dispatched which captured the Qwabe cattle and destroyed their kraals. The settlers' position was assured, and Shaka allegedly signed an agreement granting Farewell nearly four thousand square miles of land around Port Natal.

During 1826 Farewell and Fynn accompanied Shaka's army of over forty thousand warriors on an expedition against the Ndwandwe clan. The result was a total slaughter of the Ndwandwe; an event that distressed even Farewell and Fynn, though Shaka was delighted with the sixty thousand captured cattle. Shaka's disregard for human life was difficult for the Europeans to comprehend; a dozen executions a day was normal. When Shaka suspected that some of his younger warriors were visiting the girls of the isiGodlo he had two hundred youngsters summarily executed. The young women of the isiGodlo have often been misrepresented as forming a chief's harem; they were certainly a ready source of wives and concubines but were principally young women presented to a chief or king as a tribute – for him to dispose of in marriage in return for a high lobola or bride price.

Shaka's rule was total until 1827 when his mother Nandi suddenly died. Shaka's grief was so intense that he required every Zulu to experience his loss. At a gathering of some twenty thousand souls within the kraal, enforced wailing and summary executions commenced and continued for more than a day, until well over one thousand of the multitude lay dead. Shaka then decreed that during the next twelve months no crops could be grown, children were not to be conceived, or milk drunk – all on pain of death. These proscriptions continued for three months until Shaka tired of mourning, whereupon some normality returned. Shaka's wanton brutality has invariably been attributed to his allegedly repressed sexuality. This is another myth; too many contemporary Zulu accounts refer to newborn babies among Shaka's isiGodlo being put to death or smuggled away. Contrary Zulu legends, perhaps dubious, suggest Shaka had a long and faithful relationship with his sister's friend, Pampata, who supported Shaka until his death. (1)

The damage and carnage of the mourning period was such that Shaka's half brothers, Dingane and Mhlangana, agreed that Shaka must die. They waited until the army was away on campaign, then stabbed Shaka to death during a meeting with his senior indunas, the sub-chiefs. His body was unceremoniously buried in a pit, weighted down with stones. Many years later, the site was purchased by a farmer, and today Shaka's grave lies somewhere under Cooper Street in the small town of Stanger, north of Durban.

Dingane seized control but lacked Shaka's reputation, and almost immediately stirrings of rebellion began emanating from tribes who had suffered the excesses of the late king. Dingane was in dire peril, as the Zulu army was still absent on campaign against the Shangane tribe and the only regiment remaining at the royal kraal had previously been loyal to Shaka. Dingane and Mhlangana surrounded themselves with trusted warriors and awaited the return of the army. Several weeks went by, and the hitherto close relationship between the two brothers deteriorated. Dingane received a warning from a trusted spy that Mhlangana was plotting his death. That night Dingane was injured by a spear thrown under cover of darkness; and though wounded he immediately retaliated by having Mhlangana murdered. Within days the exhausted and anxious army returned in expectation of Shaka's wrath, only to be relieved when Dingane welcomed them back, fed them and then authorised their leave. Dingane thus ensured their loyalty and, being unchallenged, assumed the mantle of king. Curiously, the title ‘king’ appears to have evolved from a spontaneous gesture by Lieutenant Farewell during an early meeting with Shaka. In awe of the Zulu, Farewell took a smear of grease from the wheel hub of one of his cannons and ceremonially anointed Shaka on the forehead – after which ceremony he was referred to as‘the king'. Dingane, at no more than thirty years of age, settled into a life of luxury and security. He enjoyed singing and dancing and clearly had artistic inclinations. Unlike Shaka, Dingane was gluttonous and spent most of his time in his harem or reviewing parades of warriors and cattle. He reduced the size of the Zulu army, and Shaka's previous policy of random butchery ceased, though miscreants were still summarily executed.

In the spring of 1834 a relatively unknown incident occurred which helps explain Dingane's subsequent suspicion and treatment of white settlers. A Zulu impi returning from a minor campaign came across a small party of half-caste hunters from the Cape. Thinking the impi was about to attack them, the hunters fired several shots and within minutes were annihilated by the Zulus for their mistake. News trickled back to the settlement at Port Natal, where the Boer settlers incorrectly presumed that the impi had attacked their own hunting party who were, by sheer coincidence, in the same area but had not been involved and were unaware of the incident. The settlers retaliated by mounting a small expedition which ambushed the impi, taking the Zulus by surprise and killing scores.

The settlers returned to Port Natal fully expecting a major Zulu attack; curiously, Dingane did not retaliate. It was during this period of heightened tension that Piet Retief, leader of the trekking Boers who sought to escape British rule in the Cape, visited Port Natal while on his way to Dingane to seek settlement rights for his followers. His small party easily doubled the port's population, and it is evident that the residents welcomed the possibility of a Boer settlement in the same vicinity. To Dingane it was becoming evident that white settlement now posed a serious threat to his rule. Piet Retief was certainly unaware of the incident and of its consequences for his visit to Dingane, both for the Boers and subsequently for the Zulu nation. Retief set out to visit Dingane to seek permission to settle, but Dingane had Retief and his party killed. Shortly afterwards, Dingane was killed by his own people, and his younger halfbrother Mpande succeeded.

In 1845 Britain seized the opportunity to annex the whole of Natal into Cape Colony, including Boer-held territory. Reluctantly, the BoerVolksraad (parliament) acquiesced. The Boers had overreached themselves and in provoking the British lost sovereignty over lands won by great sacrifice. Settlers continued arriving from Europe, but the biggest change since the Boers' crossing of the Drakensberg came with the dredging and channelling of the mouth of Durban harbour. As a result of this single engineering undertaking Durban rapidly prospered as the influence of Pietermaritzburg declined. During the European upheaval in Natal, the Zulus under their new king Mpande had withdrawn to the north of the Buffalo and Tugela rivers. By now, the Zulus were under political and territorial pressure from Europeans based at Portuguese-controlled Delagoa Bay, from British-dominated Natal and by voortrekkers (Boer pioneers) north of the Tugela and Mzinyathi rivers.

Mpande ruled the Zulu nation fairly but firmly according to Zulu custom during the relatively peaceful years that followed. It was a period of consolidation after the internecine wars of 1838 and 1840, and the Zulus were also recovering from the economic impoverishment caused by white settlers' encroachment. Mpande turned his attention to the isiGodlo and feasting, until he became too obese to walk. His activities in the isiGodlo produced nearly thirty sons. The firstborn was named Cetshwayo, who was followed shortly by a brother named Mbulazi. Under Zulu custom, the heir to the throne was the firstborn male of the head wife, but Mpande never nominated such a wife. Mpande was fully aware that the question of succession would be complex; he postponed the matter by sending the two sons and their mothers to villages separated by some fifty miles. As Mpande aged, schisms developed within the Zulu nation, and gradually the subservient chiefs and clans graduated to either Cetshwayo or Mbulazi. The two brother princes were now in their early twenties and led the uThulwana and amaShishi regiments respectively, though neither had any actual combat experience. Cetshwayo was a traditionalist and hankered after the regal days of Shaka, whereas Mbulazi was more inclined to intellectual matters, though equally devious and powerful; in the year 1856 both sought to become king.

As usual, resolution came through bloody conflict, perhaps the worst seen or recorded in African history. Near Ndondakusuka hill, Cetshwayo mustered twenty thousand warriors, the uSuthu, and pitted them against Mbulazi's army of thirty thousand, the iziGqoza, which included many women and old men. The confrontation took place on the banks of an insignificant stream, the Thambo, which fed into the Tugela River. The battle lasted no more than an hour, and Mbulazi's army was heavily defeated. In customary Zulu fashion, Cetshwayo gave orders for their total slaughter, and only a handful of survivors escaped. Cetshwayo was later praised in song for his victory, as being the victor who “Caused people to swim against their will, for he made men swim when they were old”. (2)

Following the battle, Cetshwayo ordered the murder of several of his own brothers and half-brothers who could have challenged him for the kingship. Within weeks he was pronounced heir to Mpande and immediately took over the rule of the Zulu nation, leaving Mpande as a mere figurehead. Cetshwayo had observed the underlying tension between the British in Natal and the Transvaal Boers and knew this placed him in a position of considerable strength. He now had full control of Zululand, and in order to strengthen his grip further he courted the friendship of the British, whereupon Theophilus Shepstone, Secretary for Native Affairs, went to Mpande and suggested that, in the name of Queen Victoria, Cetshwayo be appointed heir apparent. Mpande accepted on behalf of the Zulus, though Cetshwayo was aware that his future now depended, to a degree, on British support. Mpande died in 1872 after thirty relatively peaceful years on the Zulu throne, a reign marred only by his two sons' recent battle by the Tugela. Mpande was the only Zulu king to die of natural causes.

Cetshwayo thus became king while in his mid-forties and immediately sought British confirmation of his position. Shepstone readily agreed, and in a sham ceremony on 1 September 1873, Cetshwayo was crowned king of the Zulu nation – in the name of Queen Victoria. He established his royal homestead at Ondini near the present-day Ulundi. Cetshwayo, perhaps the most intelligent of all the Zulu kings, now ruled a united nation. His army was at its strongest and the Zulus had a most powerful friend, Queen Victoria – and no apparent enemies.

With his military position secure, Cetshwayo began to strengthen his economic and political control. Since Shaka, young men had been obliged to serve in the army as a means of binding the nation together. The units or amabutho were the king's active service troops and in peacetime gave service at the king's command as tax officials or by undertaking policing duties. Apart from drawing young men into an amabutho for military and work purposes, this also served to accustom warriors to identifying the Zulu king as their leader, regardless of their origins. However, where young men came from an outlying area or one which had only recently been absorbed into the Zulu nation, they were allocated menial work and were known as amalala (menials), amanhlwenga (destitutes) or iziendane (unusual hairstyles).

These warriors remained in their regimental amabutho until the king authorised their ‘marriage’; this was another misunderstood concept that has often led to confusion. Zulu marriage has invariably been interpreted through European eyes with Freudian overtones of repressed sexuality, and confused with European values. To a Zulu, marriage was the most significant event of his life: it gave him the right to take a number of wives; he was free to establish his personal kraal; and he could own land for his cattle and crops. The king controlled marriage as a means of keeping his young men under arms and out of the economic structure of Zululand. Had every warrior been permitted to establish his own kraal at will, the effect on Zulu society, including both production and reproduction, would have produced economic instability. Concomitantly, by delaying the time when Zulu women could marry, the pressure of population growth could be strictly controlled and the Zulu birthrate maintained in line with economic capability.

Meanwhile, the British became occupied with minor conflicts elsewhere in southern Africa, mostly brought about by native resistance over land occupied by white settlers. Land became scarce and, in time, there was little available to offer those still en route to Natal. Severe drought throughout 1876 and 1877 made matters worse, and Britain, through its High Commissioner Sir Bartle Frere, encouraged the solution of ‘Confederation’. By combining all the territories in South Africa, Britain could control both resources and policy through a system of central and regional government. To this end, Shepstone had already annexed the Transvaal on the pretext of saving the Boers from their own bankrupt economy and to discourage the Zulus from raiding Boer farms in disputed areas of Zululand.

The British knew full well that Zululand must be included in any Confederation, principally because Zululand still possessed sufficient available land for settlement and an untapped source of labour. There remained one problem: the Zulus' autocratic king and his army of forty thousand warriors would never agree to an effective surrender and dissolution of Zululand merely to facilitate British economic development. Government officials in Natal initiated rumours of a bloodthirsty and defiant Zulu army plotting to invade Natal, and hysteria among the white settlers was fanned until conversation and newspaper reports spoke of little else. Occasional Zulu incursions against isolated Boer farmers increased, as did numbers of Bantu migrants illicitly settling in Zululand – simply because cattle were the single currency applicable to all races, and as the settlers' wealth increased, so they sought additional grazing land. Retaliatory raids encouraged European speculation that war against the Zulus was inevitable, though Cetshwayo appeared to be unaware of this subversive undercurrent. But for the Zulus the writing was clearly on the wall.

By the time the Anglo-Zulu War commenced, successive Zulu kings had efficiently controlled the development of Zulu social organisation and ensured a comparatively healthy and prosperous population. Anthony Trollope travelled through southern Africa and parts of Zululand during 1877 just as European hysteria was mounting, yet he viewed the Zulus as perceptive and living in sympathy with their time and environment. He wrote, ‘I have no fears myself that Natal will be overrun by hostile Zulus, but much fear that Zululand should be overrun by hostile Britons’. (3)

Zulu tactics

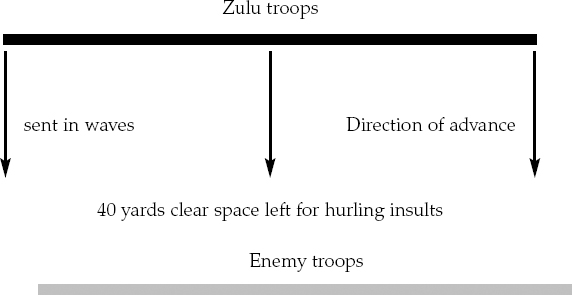

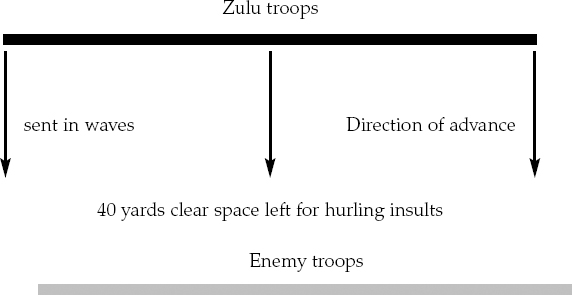

Prior to Shaka, inter-tribal warfare was not very destructive – defeated tribes lived to fight again. Shaka's new battle tactics were totally different and completely ruthless. This was demonstrated when Shaka mobilised his highly trained and efficient force against the neighbouring Buthelezi tribe. Both sides adopted the traditional abuse-hurling confrontation known as giya that usually took the form of a shouting match between the two sides separated by a gap of about forty yards. Giya usually lasted about two hours, before the two sides separated and returned to their respective home areas.

Fig. 1

Tactics before Shaka

Traditional giya formation

The Zulus thereafter used the invincible impondo zankhomo not only for inter-tribal warfare but also when hunting. These tactics had stood the test of time since Shaka; the British invading force was about to experience them for the first time.

Zulu weapons

The Zulus' tough leather shields were the most visible part of their warriors' armoury. Shields were always made by specialist shield-makers who would begin the construction by cutting a large oval from a cowhide, leaving the hair on the outer face. The colour of the hide was important. In the time of Shaka, the combination of colour and patches was carefully monitored, the differences between each regiment's colour being detailed and specific; the whiter the shield, the more senior its owner. By the 1870s the practice was less strictly observed, although married regiments carried predominantly white or red shields, while those of unmarried regiments were black, or black with white markings. The full war shield was the isiHlangu, which was intended to cover the warrior from his eyes to his ankles, and thus varied in size from one warrior to another. The largest shields of this type were as much as five feet long and two feet six inches wide. During the civil war of the 1850s Cetshwayo introduced a smaller variant called the umbhumbhulosu. Three feet six inches long and two feet wide, it was considered lighter and easier to use. In the 1870s both shields were carried, even within the same regiment, although the umbhumbhulosu may have been more popular with younger and more adventurous warriors. The shields were strengthened by a single vertical stick fastened to the back by a double row of hide strips threaded through slits carefully cut in the shield; it was held by a small handle. The bottom and top of the stick both protruded, the former sharpened to a point and the latter decorated with a strip of fur. All shields were the property of the king rather than the individual; they were kept in special raised stores, out of the way of ants and rodents.

Zulu weapons of aggression consisted of both traditional Zulu spears and obsolete European rifles. Shaka had introduced the famous Zulu stabbing spear or assegai into his army at the start of his career; this short spear had a blade some eighteen inches long and two and a half inches wide at its widest point, set into a wooden shaft two feet six inches long. He drilled his soldiers in shock tactics that involved a mass charge and close-quarter fighting, thrusting the stabbing spear underarm into the belly of the opponent. There were also a number of different types of throwing spear common in 1879, most of which had a blade of about five or six inches, with the iron shank visible for several inches before being set into a long shaft made of various easily-worked but strong woods, for example iPahla (Brachylaena discolor), iLalanyati (Grewia occidentalis), iMindza (Halleria lucida) and unHlwakele (Cyclostemon argustus).

The manufacture of assegai stabbing spears was a highly skilled craft, entrusted to particular clans such as the Mbonambi and the Cube. The iron ore was collected at surface deposits and smelted in a clay forge with the aid of goatskin bellows. The blade was hammered into shape, tempered with fat and sharpened on a stone, before being set into a short wooden shaft. It was glued with strong vegetable glues and bound with wet cane fibre. A tube of hide, cut from a calf's tail, was rolled over the join and allowed to shrink. At its best, such a weapon was tough, sharp and well designed for its purpose. However, there is a suggestion that by 1879 the importation of iron implements from white traders had led to a decline in the indigenous iron industry. Certainly there are a number of stories of blades bending or buckling in use.

Warriors were responsible for their own weapons, but the King initially received the spears in bulk from those clans that made them, distributing them to warriors who had distinguished themselves. Most warriors carried clubs or knobkerries, the iWisa, which were simple polished sticks with a heavy bulbous head. Zulu boys carried them for everyday protection, and their possession at all times became second nature. A number of axes were used; these were often ornamental and were imported from tribes to the north.

By the time of the British invasion, the Zulu army possessed firearms in large numbers. A trusted English trader, John Dunn, had imported them in quantity for Cetshwayo. During the 1870s as many as 20,000 guns entered southern Africa through Mozambique alone, most of them intended for the Zulu market. The majority of these firearms were obsolete military muskets, dumped on the unsophisticated ‘native market’. More modern types were available, particularly the percussion Enfield, and a number of chiefs had collections of quality sporting guns. Individuals like Prince Dabulamanzi and Chief Sihayo of Rorke's Drift were recognised as good shots, but most Zulus were untrained and highly inaccurate; numerous accounts of Anglo-Zulu War battles note both the indiscriminate use of their firepower and its general inaccuracy. After Isandlwana, large numbers of Martini-Henry rifles fell into Zulu hands. King Cetshwayo attempted to collect these at Ulundi to distribute them more evenly, but most warriors retained their own booty, claiming they had personally killed the man from whom they took it. Cetshwayo pragmatically allowed warriors to keep the rifles; many would shortly be used against the British.