southwestern washington

North Head Lighthouse at Cape Disappointment State Park

southwestern washington

North Head Lighthouse at Cape Disappointment State Park

Columbia River

Entering Washington’s northeast corner and exiting through its southwest corner, the mighty Columbia River snakes across the Evergreen State and threads two-thirds of its land mass into one massive watershed. A sustaining life force to the region’s First Peoples, the Columbia also allowed explorers and exploiters, settlers, and sailors access to the Pacific Northwest.

A transportation corridor, provider of power, and irrigation source for thousands of acres, the Columbia has changed much since its most famous visitors, Lewis and Clark and their Corps of Discovery, plied it two hundred years ago. And while much of the countryside that clings to the river’s shorelines has been radically altered since Boston merchant Robert Gray named the river after his vessel in 1792, wild stretches do still exist.

No dams or large settlements mar the waterway near the Columbia’s mouth on the Pacific. And while the legendary salmon runs have sadly yielded to “progress,” another kind of progress is being made in restoring some of the area’s rich estuaries and bottomland forests. Much of the hilly riverbanks are owned by private timber firms, but a few public and protected parcels grace the Lower Columbia.

On your hikes to these places, prepare to be projected back into the past. Native peoples, explorers, and hardscrabble farmers and fishermen have all left their signatures on this land. An abundant array of wildlife continues to tell the story of this fascinating corner of Washington State.

|

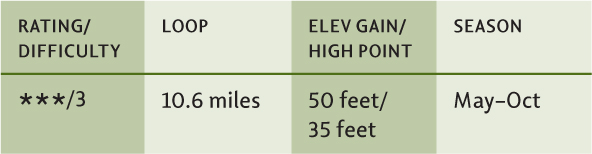

Julia Butler Hansen National Wildlife Refuge |

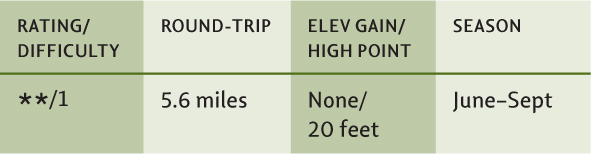

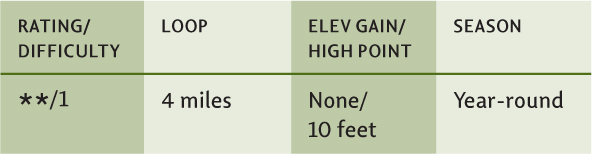

Maps: USGS Skamokawa, refuge brochure and map available at refuge headquarters; Contact: Julia Butler Hansen National Wildlife Refuge, (360) 795-3915, www.fws.gov/willapa/JuliaButlerHansen; Notes: Dogs prohibited. Wildlife closure Oct 1–May 31; GPS: N 46 15.392, W 123 26.181

|

A flat and easy hike through a rich Columbia River bottomland: explore snaking sloughs and observe a slew of bird and wildlife, including the federally endangered Columbian white-tailed deer. |

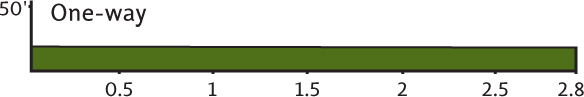

A hiker on the “Center Road” in the Julia Butler Hansen National Wildlife Refuge

GETTING THERE

From Kelso travel west on State Route 4 for 26 miles to Cathlamet. Proceed for 2 more miles, crossing the Elochoman River and then turning left onto Steamboat Slough Road (signed for the national wildlife refuge). The refuge headquarters is in 0.25 mile—stop and get a map. Continue on Steamboat Slough Road for 3.3 miles. The trailhead for Center Road is on the right, marked by a gate and hiker sign.

ON THE TRAIL

The Julia Butler Hansen Refuge for the Columbian White-Tailed Deer may be a tongue-twister of a name, but at least no ankles will be twisted on this gentle hike. Established in 1972 to protect habitat for the endangered Columbian white-tailed deer, the refuge includes bottomland forests, open pastures, river islands, and lazy sloughs that evoke the American South rather than the Pacific Northwest.

In 1988 the refuge’s name was changed to honor Julia Butler Hansen from nearby Cathlamet. Ms. Hansen served twenty-two years in the state legislature and fourteen years in Congress. She was instrumental in establishing the 5600-acre refuge.

Center Road is a gated and grassy “service road.” It marches right through the middle of the refuge, offering plenty of opportunities for spotting a few of the three hundred shy deer residing here. Elk, coyotes, otters, herons, eagles, kingfishers, and osprey are all frequently sighted if you come up short in the deer department.

The trail is only open in the summer months, and your best bet for seeing deer is early in the morning or late in the day. Center Road traverses the refuge through mostly open pasture surrounded by wetlands. Take your time to identify birds and scope out camouflaged critters in the grasses.

Center Road ends in 2.8 miles at Steamboat Slough Road near the refuge headquarters. Either retrace your steps or return via the very lightly traveled Steamboat Slough Road for a loop, adding 0.5 mile. Views along the way include wide sweeping Columbia River vistas that enticed Captain William Clark (of Lewis and Clark fame) to exclaim, “Ocian in view!” He was a little premature, but not that far off.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

The nearby Skamokawa Vista Park (a county park) makes for an excellent car-camping base, with access to a sandy river beach.

|

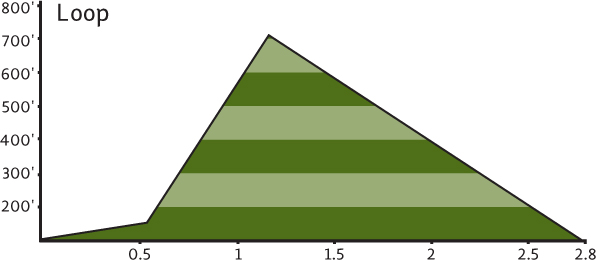

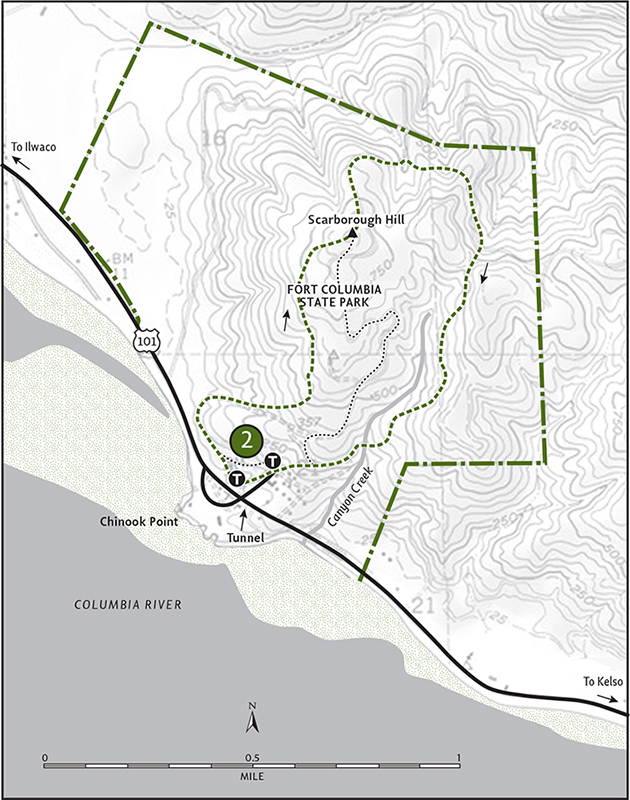

Scarborough Hill |

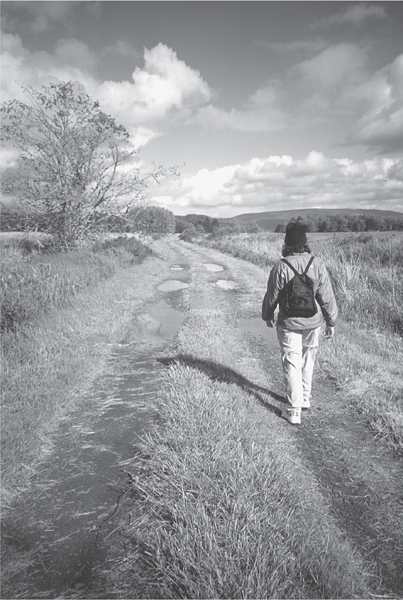

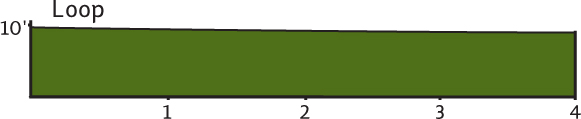

Map: USGS Chinook; Contact: Fort Columbia State Park, (360) 642-3078, infocent@parks.wa.gov, www.parks.wa.gov; Notes: Dogs must be leashed; Discover Pass required; GPS: N 46 15.251, W 123 55.261

|

Hike through a rare coastal old-growth Sitka spruce forest. Enjoy sweeping views of the mouth of the Columbia River. After your grunt up Scarborough Hill, snoop around the meticulously preserved early twentieth-century historic structures of this former military reservation. |

GETTING THERE

From Kelso follow State Route 4 west for 56 miles to Naselle. Turn left (south) onto SR 401, proceeding 12 miles to US 101 at the Astoria-Megler Bridge. Follow US 101 for 3 miles. After emerging from a small tunnel, turn left into Fort Columbia State Park and continue 0.25 mile to the large parking area west of the interpretive center. (From Ilwaco follow US 101 south for 8 miles to the Fort Columbia turnoff.) The Scarborough Trail begins at the far west end of the parking area.

ON THE TRAIL

Fort Columbia State Park sits on a scenic bluff at the mouth of the Columbia River. Established in 1899, the fort was one of several defense installations designed to protect the Columbia from enemy attack.

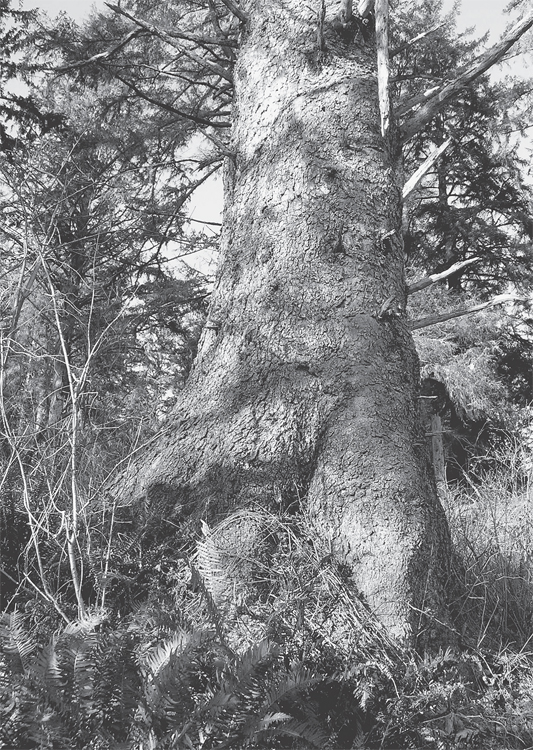

Never fired upon, Fort Columbia preserves a piece of our history and a good chunk of old-growth forest. While the area never came under enemy attack, the surrounding forests were heavily slain. But within this park’s six hunderd acres, stately giant Sitka spruce trees still stand—trees that were old when Lewis and Clark paddled by two hundred years ago.

Three hiking trails lead through these centuries-old sentinels. They wind their way up and above the tidy historic military base to 767-foot Scarborough Hill. And while the arboreal giants are the main attraction, occasional gaps in the forest canopy provide satisfying views of the massive mouth of the Columbia—its horizon-spanning jetties, lost-in-time Astoria, Oregon, and lumpy Saddle and Neahkahnie Mountains rising behind it.

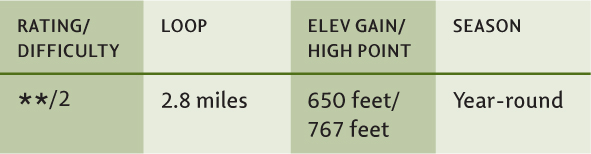

Giant Sitka spruce along the Scarborough Hill Trail

All three trails climb steeply, helping to slow you down in this timeless forest. Start your hike on the Scarborough Trail, winding around some batteries overlooking the Columbia. Then begin climbing. Pass a couple of side trails that veer to the right—they offer short-cut loop options if you’re inclined to skip the summit.

Continue through rows of spruce and alder. Admire the glaucous sheen of the alders’ smooth trunks contrasted against the spruces’ scaly purple bark. After 1.2 miles of twisting and turning through these trees, reach Scarborough Hill’s forested summit. For the longer loop back down, take a left, following the Canyon Creek Trail for 1.6 miles back to the base. Expect a good river view among yet more impressive trees. The Military Road Trail departs right, is 0.6 mile shorter, and is much easier on the knees.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Whichever way you decide to return, save some time to explore the historic grounds of the fort before heading home.

Long Beach Peninsula

Extending over 20 miles from the mouth of the Columbia River to the mouth of Willapa Bay is the Long Beach Peninsula, a jutting finger along the Pacific, lined with fine sandy beaches against a backdrop of silver dunes. Ever since Captain William Clark wandered these beaches in November 1805, tourists have been flocking here. In the late nineteenth century, well-heeled Portlanders boarded paddle ships destined downriver to this peninsula. Tidy cottages sprung up in new beach towns: Seaview, Long Beach, and Ocean Park. Oystermen settled the peninsula’s northern reaches in Nahcotta and Oysterville, once one of the richest communities in Washington.

“OCEAN IN VIEW!”

Any hiker taking to the trails and beaches of southwestern Washington will be bombarded not only with beautiful scenery, but also with history. In essence, the state’s “modern” history began here. In the late 1700s, Vancouver, Meares, Gray, Cook, and others sailed up and down the coastline, mapping, exploring, and trading with Native peoples.

It was Captain John Meares, a British sea merchant, who in 1788 named Cape Disappointment. He was disappointed at not finding the “River of the West.” He thought that the mouth of the Columbia was merely a bay. Today, hikers who take to the rugged headlands of Cape Disappointment certainly won’t be.

Lewis and Clark spent several wet November days in the region in 1805. Captain William Clark thought he sighted the Pacific near present-day Skamokawa, exclaiming “Ocian in view!” The river mouth that Meares mistook for a bay, Clark mistook for the ocean. Clark was one of the area’s first recorded hikers, climbing over North Head at Cape Disappointment and on to Long Beach. Today you can trace his journey on the paved and gravel Discovery Trail that leads from Ilwaco to Long Beach.

Willapa Bay, once known as Shoalwater Bay, helped feed the forty-niners of San Francisco (the gold rushers, not the football players) with succulent oysters. But while Europeans and Americans of European and Asian descent were settling and shaping what would become Pacific, Wahkiakum and Grays Harbor Counties, Native peoples had little to say about this change. On July 1, 1855, at the mouth of the Chehalis River near Grays Harbor, Washington’s first territorial governor, Isaac Stevens, brought together coastal tribes to sign a treaty stipulating that they relinquish their land. The tribes didn’t capitulate—it wouldn’t, however, be Stevens’s last attempt.

You can reflect on our state’s fascinating and sobering human history while hiking the beaches and trails of southwestern Washington.

Today, beachcombers still enjoy the Long Beach Peninsula, and oyster harvesting is still a viable part of the local economy. For day hikers, the peninsula offers two prime destinations, one on each end of the elongated land form. Cape Disappointment to the south, with its rugged headlands and old-growth forests, is one of Washington’s most popular state parks. Leadbetter Point, on the north end, consists of the state’s wildest coastline south of Olympic National Park and is a bird watcher’s version of heaven.

And while the state still allows vehicles to maraud the peninsula’s beautiful beaches (note to legislators: the beaches are no longer needed for mail and goods delivery, State Route 103 does just fine), at Leadbetter Point and Cape Disappointment you and the resident wildlife are free to wander free from exhaust.

|

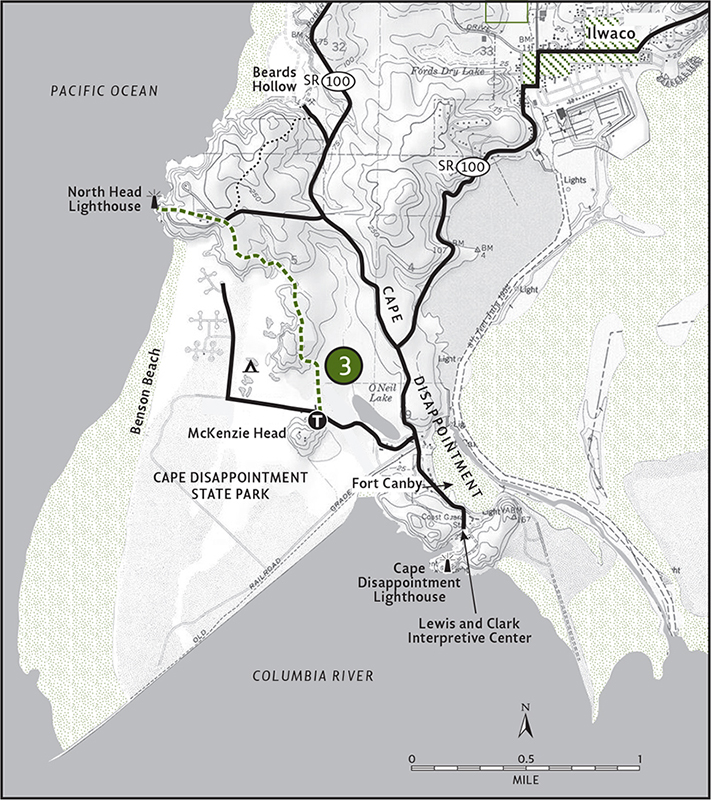

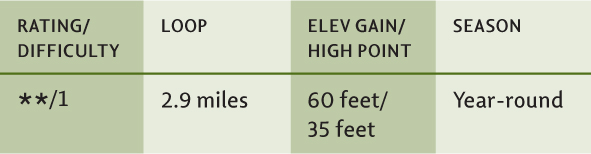

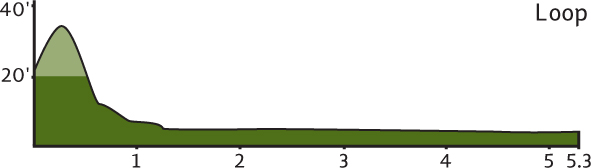

Cape Disappointment State Park |

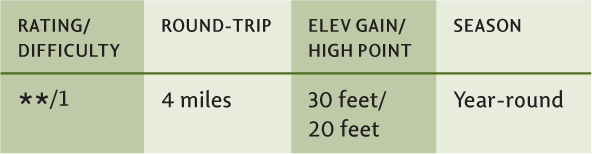

Map: USGS Cape Disappointment; Contact: Cape Disappointment State Park, (360) 642-3078, infocent@parks.wa.gov, www.parks.wa.gov; Notes: Dogs must be leashed; Discover Pass required; GPS: N 46 17.136, W 124 03.796

|

Take the long and scenic way to Cape Disappointment’s North Head Lighthouse. Through a salt-sprayed maritime forest, trace part of Captain Clark’s hike on the Long Beach Peninsula. From the high headland that houses the 1898 lighthouse, take in breathtaking views that include thundering waves, windswept dunes, and scores of shorebirds skimming the crashing surf. |

GETTING THERE

From Kelso follow State Route 4 west for 56 miles to Naselle. Turn left (south) on SR 401, proceeding 12 miles to US 101 at the Astoria-Megler Bridge. Continue on US 101 for 11 miles to Ilwaco and the junction of SR 100. Follow SR 100 (it’s a loop, bear left) to Cape Disappointment State Park, and in 2 miles turn left into the park. Drive 0.5 mile to a four-way stop and turn right. Pass the entrance station, and in 0.25 mile turn right again. In 0.4 mile come to the McKenzie Head trailhead and park here.

ON THE TRAIL

There are over 6.5 miles of hiking trails in 1884-acre Cape Disappointment State Park. Once home to Fort Canby, a military reservation established in 1852 (before Washington statehood), the state park was created in the 1950s. Most of its trails are short. All are scenic. The 1.8-mile North Head Trail is the longest, traversing a moisture-dripping old-growth Sitka spruce forest and offering spectacular ocean views along the way. It ties into several other trails, allowing for extended explorations.

The trail to North Head starts through a flat marshy area before heading up onto a small rugged ridge. When Lewis and Clark visited this area, the ridge was a headland protruding into the Pacific. After the North Jetty was built in 1917, this marshy forested area formed through accretion (trapped sand and silt accumulation). The land mass and beaches of Cape Disappointment are growing (and they say land doesn’t grow!).

On what can be a muddy trail, climb above the old coastline on this former headland. Giant Sitka spruces keep you well-shaded, while gaps in the forest canopy offer splendid views down to the “new” beach. In 1.8 miles from the trailhead, come to a parking lot. (Yes, you could have driven to this point—but why? Exercise and nature are good for your body and soul!)

Now hike the 0.3-mile trail down to the North Head Lighthouse for one of the finest maritime settings in all of Washington. Return the way you came.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Continue from the upper parking lot on the Westwind Trail for a 1-mile journey down to Beards Hollow on the beach. After you’ve returned to your car (or before you head out), consider making the quick 1-mile round trip up McKenzie Head. From this old World War II battery, admire the mouth of the Columbia River and the Cape Disappointment Lighthouse—completed in 1856, it’s the state’s oldest. The park also offers great car camping, including yurts, if you feel like sticking around to sample a few more of its wonderful trails.

Rugged headlands are one of the highlights in Cape Disappointment State Park.

|

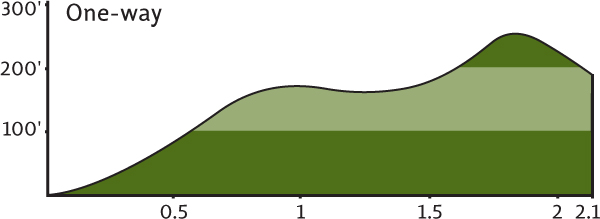

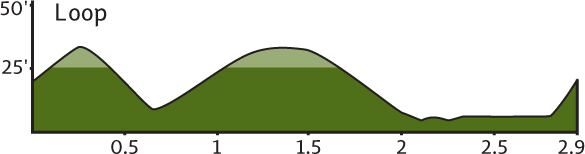

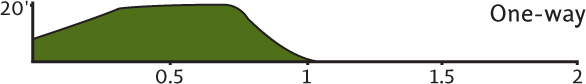

Leadbetter Point State Park: Dune Forest Loop |

Map: USGS Oysterville; Contact: Leadbetter Point State Park, (360) 642-3078, infocent@parks.wa.gov, www.parks.wa.gov; Notes: Dogs must be leashed; Discover Pass required; GPS: N 46 36.421, W 124 02.629

|

A great loop any time of year: explore quiet maritime forest and the bird-saturated Willapa Bay shoreline on the wild northern tip of the Long Beach Peninsula. Chances are good that you’ll sight bear, deer, or otter along the way. |

GETTING THERE

From Kelso follow State Route 4 west for 60 miles to US 101. Head south on US 101 for 15 miles, and just before entering Long Beach turn right (north) onto Sandridge Road (signed “Leadbetter Point 20 miles”). In 11.5 miles come to a junction with SR 103. Continue north on SR 103. In 7.3 miles enter Leadbetter Point State Park. Continue another 1.5 miles to the road end and trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

Leadbetter Point consists of Washington’s wildest coastal lands outside of Olympic National Park. Undeveloped and untrammeled, over 3000 acres of dunes, salt marshes, and maritime forest and more than 8 miles of vehicle-free ocean and bay beaches are protected within a state park and a national wildlife refuge.

Pacific Tree Frog-a common resident around Willapa Bay

Over 6 miles of trail traverse 1200-acre Leadbetter Point State Park and offer access to both the Pacific and the adjacent Willapa National Wildlife Refuge. While most hikers may be enticed to head directly to Leadbetter Point’s wide, sandy ocean beach, the area’s real charms lie within its diverse bay and forest ecosystems. The Dune Forest Loop is a great introduction to these wildlife-rich habitats. And if you’re looking for a good winter hike in the region, this loop isn’t subject to the flooding that keeps the coastal trails under water for half the year.

Start your loop by heading left (west) on the Red Trail, also known as the Dune Forest Loop. Solid tread soon yields to loose sand, slowing your momentum. In 0.5 mile come to a junction with the Blue Trail, which leads 0.8 mile to the Pacific. Continue left, hiking along a sand ridge—an old dune that has since been colonized by shore pine, wax myrtle, salal, and bearberry (kinnikinnick). After another 0.5 mile the trail turns inland (east). As the sound of the surf fades into the distance, Sitka spruce begins to dominate the forest.

In 2.1 miles from the trailhead come to the park access road (and an alternate trailhead). Cross the road, making your way to Willapa Bay. The trail now turns north for 0.8 mile, hugging the shoreline of the bay. Enjoy views of the expansive bay set against a backdrop of rolling, cloud-hugging hills. Birdlife is profuse. Pelicans, marbled godwits, loons, grebes, mergansers—over a hundred species in all ply these waters and saltflats. Eagles can often be spotted on overhanging snags. Mammals are abundant too. If hiking during low tide, scan the mudflats for raccoon, bear, and elk tracks. In 2.9 miles close the loop.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

A 1.1-mile interpretive loop, the Bay Trail makes for a nice mileage boost.

|

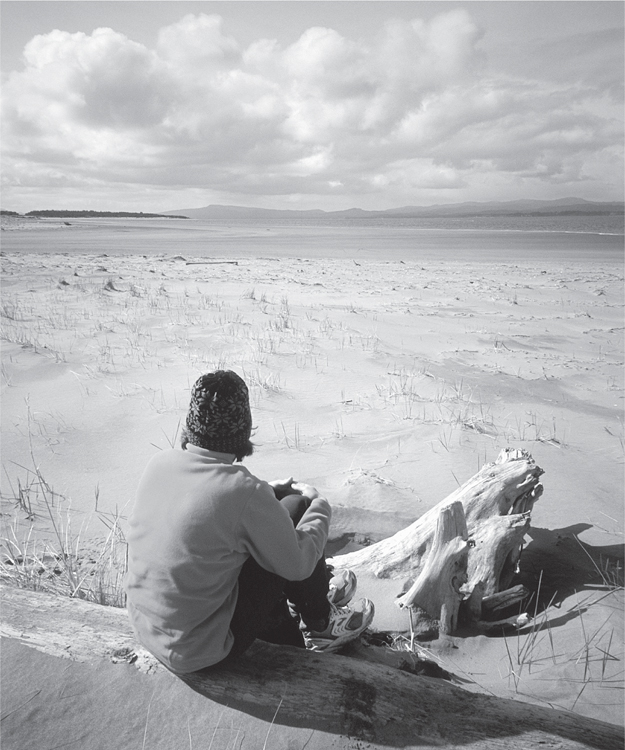

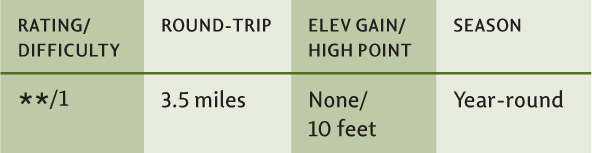

Leadbetter Point State Park: Leadbetter Point |

Maps: USGS Oysterville, USGS North Cove, refuge map available at headquarters on US 101 near milepost 24; Contact: Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, (360) 484-3482, www.fws.gov/willapa/WillapaNWR; Notes: Dogs prohibited. Discover Pass required; Removal of plants or animals from refuge is prohibited. GPS: N 46 36.421, W 124 02.629

|

Hike to the loneliest stretch of beach south of the Olympic Peninsula. Traverse thick maritime forest cloaked in bearberry and salal before emerging on a windswept beach guarded by phalanxes of high dunes. Feeling energetic? Hike all the way to the wild tip of Leadbetter Point for an all-day 10.6-mile journey. |

GETTING THERE

From Kelso follow State Route 4 west for 60 miles to US 101. Head south on US 101 for 15 miles, and just before entering Long Beach turn right (north) onto Sandridge Road (signed “Leadbetter Point 20 miles”). In 11.5 miles come to a junction with SR 103. Continue north on SR 103. In 7.3 miles enter Leadbetter State Park. Continue another 1.5 miles to the road end and trailhead. Privy available.

A hiker takes a break from a winter hike at Leadbetter Point

ON THE TRAIL

Leadbetter Point’s forests, salt marshes, its Willapa Bay shoreline, and its mudflats are prime scoping grounds for bird-watchers. This wild northern tip of the Long Beach Peninsula contains some of the best breeding and staging grounds on the entire West Coast for a myriad of species, from snowy owls to snowy plovers. Hikers intent on adding to their bird life lists should take to the area’s trails. But if you’re intent on stretching your legs, set your sights on Leadbetter’s beaches, among the finest in the Pacific Northwest.

Before beginning, take note. Both the ocean and bay beach trails are subject to flooding from November through April. We’re talking knee-to thigh-deep of cold tannic water inundating a half-plus mile of each trail. Now, on several occasions, I’ve donned sport sandals and plodded through the limb-numbing waters. It’s sort of fun—like exploring a southern swamp but without the snapping turtles, leeches, and alligators. But unless you have a high tolerance for cold water, wait until the trail dries out sometime in late spring.

From the trailhead head west on the Red Trail (a.k.a. Dune Forest Loop) for 0.5 mile to a junction and take the Blue Trail right. Follow this good path for 0.8 mile through low-lying shrubs and thick maritime forest before breaking out into high dunes adorned with swaying sedges. Reach the beach and behold a wide sandy strand void of people. Head north for 0.5 mile, entering the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge (dogs prohibited beyond this point). Locate the trail sign for the “Yellow Trail (a.k.a. Bear Berry Trail). This is your return route to the trailhead.

You can return from this point for a 3.6-mile loop, or continue trekking on the beach all the way to Leadbetter Point. It’s a 3.5-mile journey to the constantly shifting northern terminus of the peninsula. Along the way admire one of the largest undisturbed dune complexes in the state (stay out of them though: endangered snowy plovers nest here). Reach the tip of the peninsula and admire the wild and treacherous mouth of Willapa Bay. After snooping around or taking a quiet beachside nap, retrace your steps back to the Yellow Trail.

This good trail makes a 1.8-mile return via fine stands of shore pine crowded in thickets of bearberry. A short stint along a sandy Willapa Bay beach caps off the hike before delivering you to your point of origin.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

During low tide you can continue beyond Leadbetter Point for 1.5 miles on good sandy bayside beach. But don’t think about returning to the trailhead via the bay side. Salt marshes, mudflats, and snaking sloughs make travel extremely difficult.

Willapa Bay

Willapa Bay is the second-largest estuary on the Pacific Coast—only San Francisco Bay is larger. But unlike that California estuary, which is home to over seven million people, Willapa Bay is practically deserted. Pacific County, which contains Willapa Bay, has a population of just over twenty thousand. And though settlements along Willapa’s shores are among the oldest in the state (Oysterville was founded in 1854), much of the 260-square-mile estuary looks as it did when British captain John Meares first sighted and named it Shoalwater Bay in 1788.

Early settlers were attracted to the region’s abundant oyster beds and adjacent timbered hills. They diked the salt marshes for dairy farming. But despite all of this bounty and activity, no big population centers developed and no jetties were ever constructed at Willapa’s mouth—dunes and sand bars continue to shift as nature intended.

In 1937 President Franklin D. Roosevelt established the Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, ensuring that a large portion of this prime and productive estuary would remain a healthy ecosystem. The refuge consists of three main parcels (management units), and each one is unique. Leadbetter Point (Hikes 4 and 5) has wild beaches and high dunes. The Lewis and Riekkola Units (Hike 6) consist of reclaimed farmland, extensive mudflats, and the mouth of the Bear River. The Long Island Unit (Hike 7) protects the largest estuarine island on the West Coast and a cedar grove nearly one thousand years old.

Willapa Bay can be hiked all year, but take note: the refuge is managed for hunting and is popular with elk and bird hunters. Plan your hikes accordingly and respect these users—they help fund public-land acquisition and most of them have high conservation ethics. Visit the refuge headquarters along US 101 near milepost 24 for a map and information on the area’s wildlife.

|

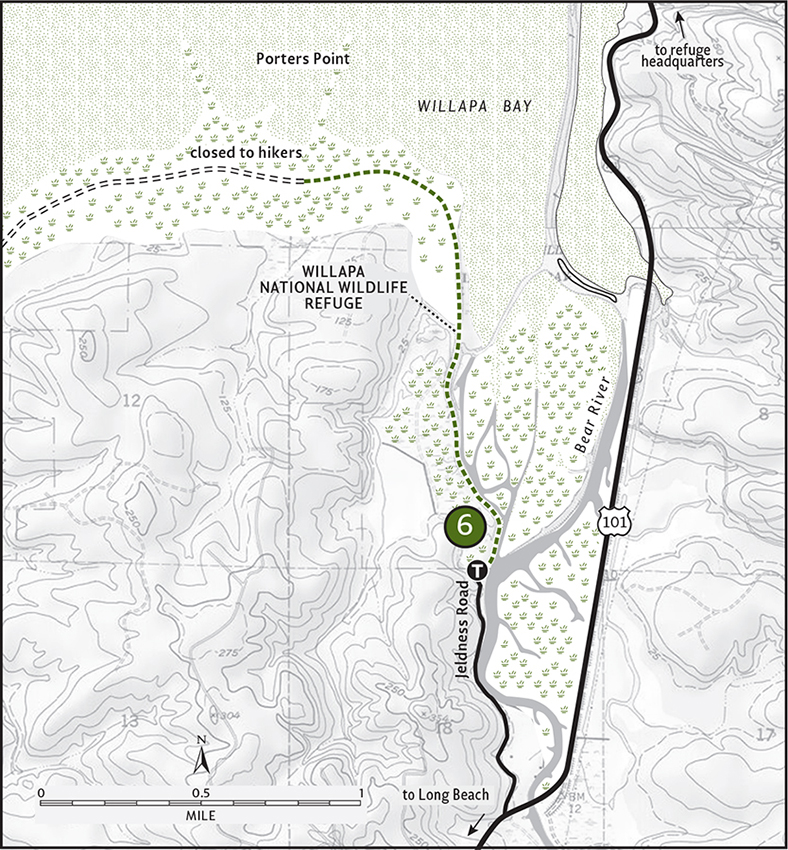

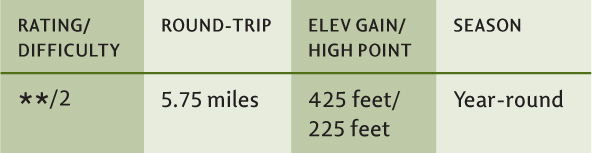

Willapa National Wildlife Refuge: Bear River |

Maps: USGS Chinook, refuge map available at headquarters on US 101 near milepost 24; Contact: Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, (360) 484-3482, www.fws.gov/willapa/WillapaNWR; Notes: Dogs prohibited; GPS: N 46 21.551, W 123 57.691

Warning: This hike is now CLOSED due to dike breaching and access issues on Jeldness Lane, the road to the former trailhead. Jeldness Lane and lands abutting it are private property and are NOT open to public use.

|

Follow the lazy and snaking Bear River to the sprawling mud and salt flats of Willapa Bay. During low tide look out over a landscape that glistens. Listen to it belch and gurgle. Watch herons spear fry, osprey drop from the sky, and otters playfully slide. Observe critters large and small, from grazing elk on the forest edge to singing frogs in trailside pools. On an old dike elevated just a few feet above the flats, dry feet are guaranteed as you hike through this saturated landscape. |

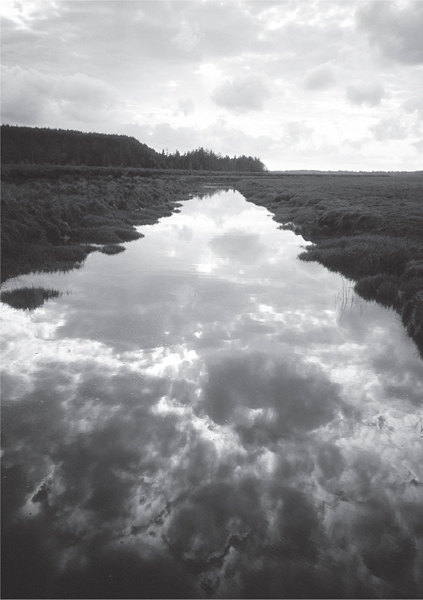

Evening clouds reflecting on Bear River

GETTING THERE

From Kelso follow State Route 4 west for 60 miles to US 101. Head 10 miles south on US 101. Immediately after crossing the bridge over the Bear River, turn right (north) onto Jeldness Road (signed “Willapa NWR Lewis Unit”). Proceed 1 mile to the road end and trailhead.

ON THE TRAIL

Start your hike on the dike/trail by passing through a gate and immediately entering a world surrounded by water. With the Bear River on your right and freshwater lagoons on your left, abundant and varied birdlife constantly vie for your attention. But the views are good too. The Bear River Range rises over the eastern flats. To the north, the golden bluffs of Long Island’s High Point adds relief to the bay’s seemingly featureless horizon.

But as you hike farther along the dike, patterns emerge in the immediate landscape. The river channels into slithering sloughs that slice through swales of swaying grasses and across mounds of mud. Geese, cormorants, blackbirds, ducks, kingfishers, sparrows—the flats and sloughs are alive with avian activity.

In 0.75 mile a spur trail branches between lagoons, heading for higher ground. In another 0.25 mile a bridge spans a channel, allowing access to the mudflats. Come to yet another bridge in another 0.5 mile. Explore the mud and salt flats—but be sure you’re wearing good waterproof boots. The dike/trail continues for another mile, but is open to hikers for only another 0.25 mile. Enjoy good bayside views of the Long Beach Peninsula from the turnaround point.

|

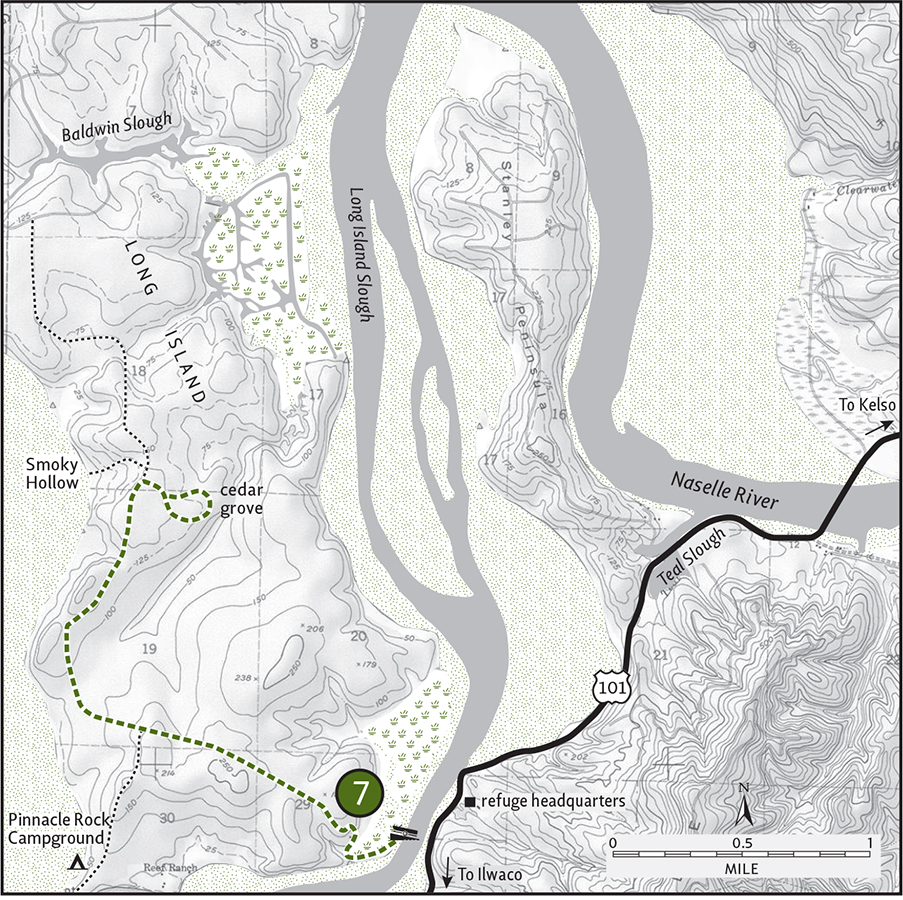

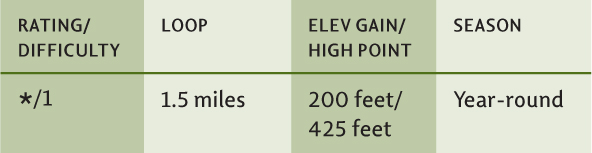

Willapa National Wildlife Refuge: Long Island |

Maps: USGS Long Island, refuge map available at headquarters on US 101 near milepost 24; Contact: Willapa National Wildlife Refuge, (360) 484-3482, www.fws.gov/willapa/WillapaNWR; Notes: Dogs prohibited. Boat needed to access trailhead; heavy hunting activity Sept–Nov. GPS: N 46 24.739, W 123 56.385

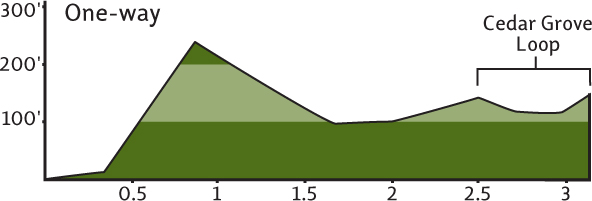

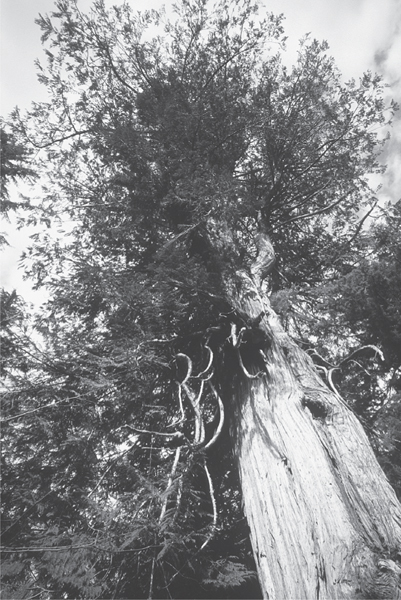

The largest estuarine island on the entire Pacific Coast, Willapa Bay’s Long Island is indeed a special place to hike. Miles of trails and old woods roads traverse this 5460-acre land mass, allowing access to quiet tidal flats, scenic bluffs, hidden sloughs, and old townsites. But the biggest attraction on Long Island is its biggest attraction—a grove of giant cedars almost one thousand years old!

Giant ancient cedar on Long Island

GETTING THERE

From Kelso follow State Route 4 west for 60 miles to US 101. Head south on US 101 for 4.75 miles to Willapa National Wildlife Refuge headquarters. (From Ilwaco follow US 101 north for 13 miles.) Park at the headquarters and launch your watercraft to reach the trailhead on Long Island.

ON THE TRAIL

The hike to Long Island’s ancient cedars isn’t overly difficult—it’s getting to the trail that may cause some problems. There’s no bridge to the island. You’ll need your own canoe, kayak, or other kind of boat to make the short channel crossing to the trailhead. Be sure to check in at refuge headquarters (located across from the boat launch) for bay conditions. Mudflats and weather can make the crossing tricky at times.

Once on the island, secure your watercraft and get hiking! Home to settlements and sawmills during the past century, most of Long Island has been logged. Amazingly, however, a 274-acre tract of old-growth western red cedar was spared from the chainsaw. In 1986 this primeval patch—the last large coastal old-growth forest grove left in Washington—was protected and added to the wildlife refuge. In 2005 the grove was named in honor of Don Bonker, a former congressman from Vancouver who played a major role in preserving these majestic trees.

The road/trail starts off on a beautiful point with nice views south of Willapa Bay’s extensive mudflats. Through second-and third-growth forest the trail winds its way inland, climbing a couple of hundred feet in the process. Woodland birds—kinglets, juncos, flycatchers, and chickadees—flit in the regenerating forest. Long Island is full of life. Bear, elk, deer, and cougar all take residence here.

In 1 mile come to a junction. The trail left leads approximately 0.5 mile to Pinnacle Point, a good place for observing elk. Continue on the main trail, and at 2.5 miles come to another junction. Take the trail right—a cedar sign indicates this way to the Don Bonker Ancient Grove. A few big stumps greet you first—then bang! Complete trees! Giant trees! Ancient trees! An old-growth cathedral of trees and you’re the sole parishioner. The trail makes a 0.75-mile loop, touching just the periphery of this special grove so as not to disturb this endangered ecosystem. Walk quietly, walk slowly—enjoy and embrace this forest that has defied the centuries. When you’re ready to be projected back into the present, retrace your steps.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Inquire at the refuge headquarters about how to get to nearby Teal Slough. There you’ll find another ancient cedar grove. It’s smaller, but the trees are grander—some of the largest specimens I have seen in the coastal Northwest. Hike the Salmon Art Trail while at the headquarters. Created by art students from the University of Washington, this unique 0.75-mile interpretive trail is lined with sculptures and images reflecting the area’s wildlife.

|

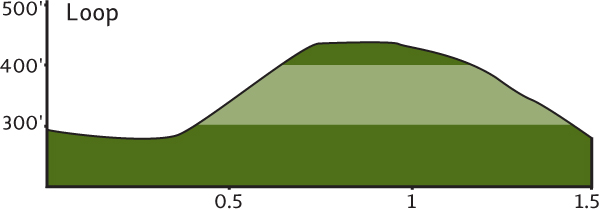

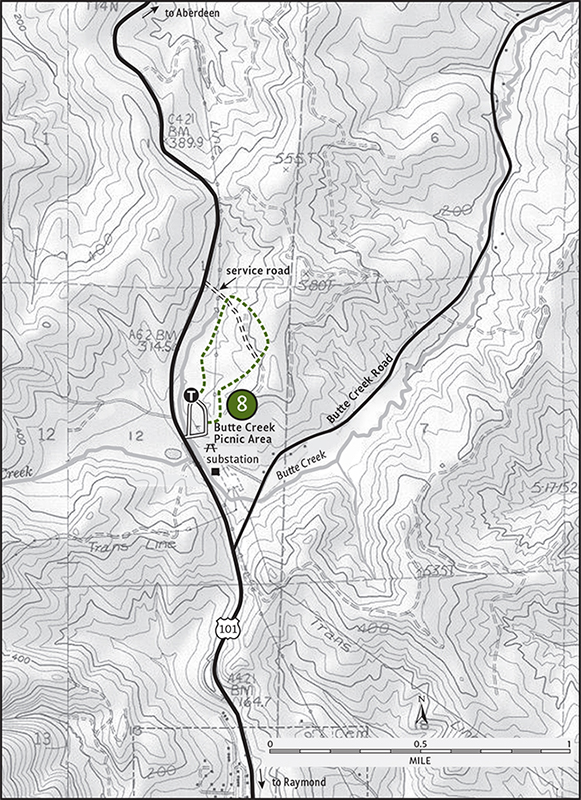

Butte Creek Sitka Spruce Grove |

Map: USGS Raymond; Contact: Department of Natural Resources, Pacific Cascade Region, (360) 577-2025, pacific-cascade-region@wadnr.gov, www.dnr.wa.gov; Warning: Trail has endured storm damage and is difficult to follow due to toppled trees and subsequent logging; Notes: Dogs must be leashed. Discover Pass required; Picnic area open May 1–Nov 1. Park at gate when picnic area closed; GPS: N 46 42.965, W 123 44.557

Old-growth Sitka spruce are the star attraction at Butte Creek

|

Hike through an old-growth Sitka spruce forest just minutes from the mill town of Raymond. Butte Creek’s magnificent ancient grove of trees is a small remnant of the grand forests that once covered the surrounding Willapa Hills. |

GETTING THERE

From Raymond travel north 2.5 miles on US 101. (From Aberdeen follow US 101 south for 23 miles.) Butte Creek Picnic Area is on the right (east) just beyond milepost 61.

ON THE TRAIL

All along US 101 as it winds around Willapa Bay, timber-company signs announce when the surrounding forest was cut, replanted, and when it will be cut again. Almost the entire Willapa watershed has been logged over at least twice. Green gold, these trees fueled local economies and helped build this nation. But sadly, very little remains of the original forest that once lined the salty marshes and covered the scrappy hills surrounding Willapa Bay.

At Butte Creek, a small but beautiful grove of old-growth Sitka spruce still stands. Here you can hike among stately trees and revel in their majesty. Be thankful that this grove exists, but also lament that we didn’t set aside a few others in the area as well.

Start your hike by a sign that says “Unimproved Trail.” Don’t let that fool you—the trail is very improved, built well and well-cared for but “unimproved” because it can’t accommodate wheel chairs. The Butte Creek Trail makes a loop about 1.5 miles long, returning back to the picnic area just to the south of where you began. Various side trails lead off the main path, allowing for shorter loops and variations. The main trail winds its way through a dark forest dominated by spruce with a sprinkling of Douglas-fir and hemlock. Moss carpets everything within this lush environment.

A small stream runs through the parcel, and the main trail crosses it several times on good bridges. The trail runs along Butte Creek for a short distance before crossing a service road, climbing a little, and then looping through a younger forest. The trail then recrosses the service road to remerge in the ancient grove. Cross a creek, come to an “overlook,” and then close the loop on an “improved” trail.

This area was once part of an old homestead. Now, with the cooperation of the Washington State Department of Natural Resources, students from nearby Raymond High School have staked a claim here. They help maintain the trails and facilities of Butte Creek—and hopefully, like you upon hiking this area, they have gained a better understanding and appreciation for our dwindling old-growth forests.

Chehalis River Valley

The Chehalis River forms a big horseshoe in southwestern Washington. Oxbowing and flowing gently through a wide and low valley, it’s a lazy river for much of its 100-plus-mile course. From its beginning in the cloud-cloaked Willapa Hills, the Chehalis flows northeast through rural countryside to the small cities of Centralia and Chehalis. Here, surrounded by lush pastures, the river bends westward, cutting a low divide between the Willapa and Black Hills. As the Chehalis gets closer to its outlet, Grays Harbor, it takes on the characteristics of a southern low-country river; a waterway lined with moss-draped trees fanning out into a labyrinth of sloughs.

Very little wild country remains along the Chehalis. Logging, farming, and creeping urbanization have taken a toll on the natural communities of this large watershed. Old growth remains only in a few small pockets. Very little remains, too, of the biologically diverse prairies and oak savannas that once graced this river’s lower reaches.

Most of the Chehalis River valley remains in private ownership. It’s a good river to paddle but a difficult one to discover on foot. Fortunately, there are a few natural gems along this waterway in public ownership. They help preserve some of the rich natural history of this region as well as introduce hikers to this oft-overlooked part of the state.

And while the Chehalis Valley lacks pristine natural areas, it’s rich in history. Hopefully someday the area’s history will include a chapter on how its forests, prairies, and hills were restored to healthy and vibrant ecosystems.

|

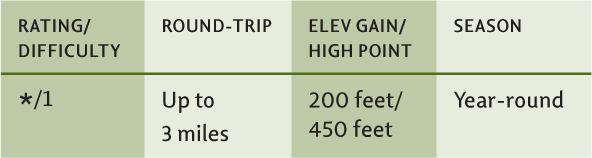

Rainbow Falls State Park |

Map: USGS Rainbow Falls; Contact: Rainbow Falls State Park, (360) 291-3767, infocent@parks.wa.gov, www.parks.wa.gov; Notes: Dogs must be leashed. Discover Pass required; Park sustained serious flood damage in December 2007; consult ranger for current status; GPS: N 46 37.812, W 123 13.911

|

Hike through some of the last standing old-growth trees in the Chehalis Valley. Admire trails, bridges, and structures built by the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Once finished hiking, sit by a small cascade and let it lull you to rest. |

GETTING THERE

From Chehalis (exit 77 on I-5) follow State Route 6 west for 16 miles to Rainbow Falls State Park. Park on south side of the highway or in the day-use area 0.3 mile from the park entrance.

ON THE TRAIL

This little state park on the upper reaches of the Chehalis River has been attracting visitors since the early twentieth century when it was a community park. Once surrounded by thousands of acres of old-growth forest, the only ancient trees left standing in this region are within the 139 acres of the park. While it’s the small cascade, Rainbow Falls, that lures people here, it’s the remnant old growth that’s the real big attraction.

About 3 miles of interconnecting trail wind through the lush tract of big cedars, hemlock, Douglas-fir, and the occasional Sitka spruce. Beneath the lofty canopy, alders are draped in moss and the forest floor is carpeted in oxalis. It’s a fairy-tale forest where chickarees and chickadees frolic and flit like gregarious elves in a magical kingdom.

From the trailhead you can set out in several directions and blaze your own course. Trails are signed and you really can’t get lost; all trails loop back to the trailhead. The Oxalis Loop passes by some of the larger trees in the park, while the Woodpecker Trail descends into a small lush ravine complete with a bubbling brook. Hike these trails as a journey—not toward a destination—and enjoy this special tract of remnant wild country.

Old-growth cedar at Rainbow Falls State Park

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

After your hike, take time to see the rest of the park, including the CCC-built structures and Rainbow Falls, a small cascade tumbling over basalt ledges. If you’d like more hiking, head to the Willapa Hills trailhead located near the campground. This former railroad right-of-way is now a multiuse trail administered by Washington State Parks. Much of the 56-mile trail is still pretty rough, but the 7-mile section from the park to the old Pe Ell Depot is graded with crushed gravel. It makes for a good hike with lots of Chehalis River and Willapa Hills views.

|

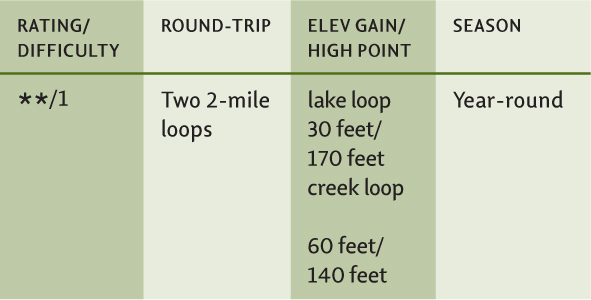

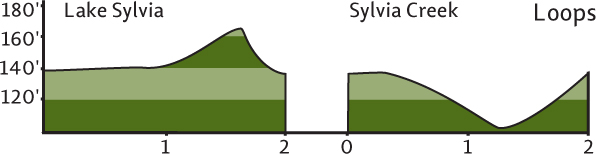

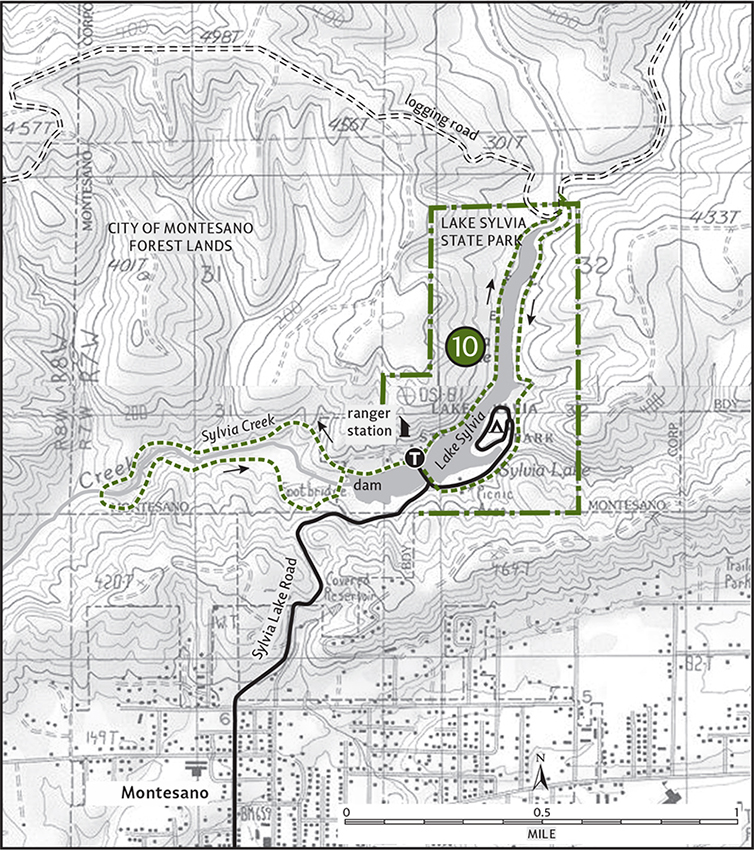

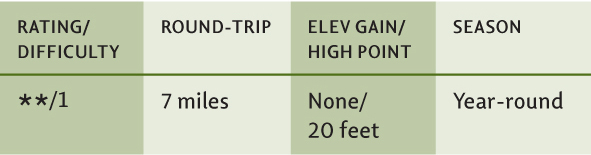

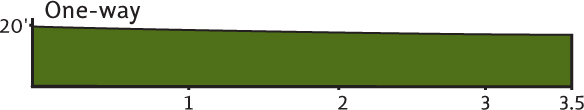

Lake Sylvia State Park |

Map: USGS Montesano; Contact: Lake Sylvia State Park, (360) 249-3621, infocent@parks.wa.gov, www.parks.wa.gov; Notes: Dogs must be leashed; Discover Pass required; GPS: N 46 59.841, W 123 35.643

|

Two 2-mile loops in a 237-acre state park not too far from downtown Montesano. Enjoy an easy hike through mature forest along a sliver of a lake teeming with fish and birdlife. Then amble alongside a babbling creek to appreciate engineers past (those who conducted trains) and engineers present (furry ones who build dams). |

GETTING THERE

Exit US 12 in Montesano and head north on Main Street past a traffic light and the scenic county courthouse. Turn left on Spruce Avenue, proceeding three blocks. Turn right on 3rd Street, which eventually becomes Sylvia Lake Road, and drive 1.2 miles to Lake Sylvia State Park. At the park entrance booth turn left, then cross the bridge and park at the day-use area near the ranger residence.

ON THE TRAIL

Lake Sylvia State Park packs a lot of history, natural beauty, and recreation within its tight borders. Once an old logging camp, the area was converted into a park in 1936. The narrow lake was created by damming Sylvia Creek, first for rounding logs and then for providing Montesano’s electricity. Plenty of artifacts and evidence remain in the park from its early days. But hikers will be pleasantly surprised to see how well the area’s forests have recovered. Mature trees hover above the lake and creek, providing not only a pretty backdrop, but also some great wildlife habitat.

This hike consists of two loops originating from the same origin. Start out near the boat launch, hiking north along Lake Sylvia’s west shore on a perfectly level path that once housed tracks for a logging railroad. No gasoline motors are allowed on the lake, providing paddlers and hikers a peaceful environment. Mature evergreens shade the trail while large alders drape over the tranquil waters. The northern end of the lake is marshy, providing good cover for ducks, geese, and herons.

In 1 mile you’ll hit an old logging road. Turn right, cross Sylvia’s inlet stream, and then turn right again to hike back along the lake’s eastern shore. The return trail is wilder, climbing over bluffs and darting in and out of cool side ravines. You’ll emerge in the park’s attractive campground (a great weekend base). Walk the campground access road a short distance back to the entrance booth, cross the bridge, and return to your start.

Refill water bottles and head south along the lake for the second loop. Cross a cove on an old railroad bridge (now a beloved fishing spot) and head to the start of the Sylvia Creek Forestry Trail. Follow this 2-mile loop through adjacent City of Montesano City Forest. Along the creek and through cool forests of maple and cedar, keep an eye out for more evidence of past human activity (such as old springboard cuts and railroad trestles). Look, too, for signs of animal activity. Beaver are active along this stretch of the creek. Close the loop by crossing the old human-built dam that created Lake Sylvia. Enjoy the view before returning to your vehicle.

An old rail bridge across Lake Sylvia is now a hiker’s favorite spot.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Nearby Vance Creek County Park in Elma (east along US 12) contains a lovely 0.75-mile paved path around a small pond.

|

Chehalis River Sloughs |

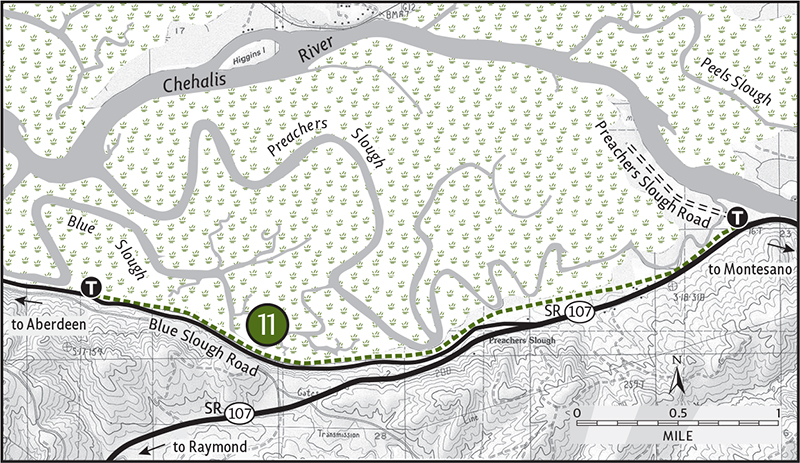

Map: USGS Central Park; Contact: Department of Natural Resources, Pacific Cascade Region, (360) 577-2025, pacific-cascade-region@wadnr.gov, www.dnr.wa.gov; Notes: Dogs prohibited; Discover Pass required; GPS: N 46 56.692, W 123 39.028

|

A “slough” of surprises awaits you on this wonderful interpretive trail developed by the Washington State Department of Natural Resources. Journey through the wildlife-and history-rich Chehalis River Surge Plain Natural Area Preserve via an old logging rail bed. Along snaking sloughs and through a tunnel of greenery, you may think you’re hiking in Louisiana instead of Washington. |

GETTING THERE

From Montesano follow State Route 107 west for 4 miles. Turn right on Preachers Slough Road (signed for hiking) and proceed 0.1 mile to the eastern trailhead. (From Aberdeen travel south on US 101 for 3 miles to Cosmopolis. Just beyond the Weyerhaeuser mill, turn left onto the Blue Slough Road and drive 5 miles to SR 107, passing the western trailhead. Turn left and continue for 1.2 miles to the Preachers Slough Road turnoff.) Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

From 1910 until 1985, trains rumbled through this saturated bottomland of scaly-barked spruce and speckled-bark alder. A few years back, trail crews from the Cedar Creek Correctional Camp helped transform the abandoned line into a great little trail. Hikers can now get onboard for a trip back in time and into the deep recesses of this productive ecosystem. While chugging along, plan for plenty of stops at the numerous viewing platforms and interpretive plaques along the way.

From the eastern trailhead, start by crossing a swampy pool on a firm bridge and then, with all due respect to the late great Johnny Cash, walk the line. Through a lush understory of vegetation the trail brushes up against Preachers Slough. Winter’s lack of greenery allows for better viewing and the guarantee of a mosquito-free journey. In 0.5 mile reach a viewing platform that juts out over the lazy waterway. Just a few miles from the Chehalis River’s outlet in Grays Harbor, this area is influenced by tidewaters. As the tide comes in, the heavy saltwater sinks, lifting freshwater to the top and forcing it to flood the surrounding bottomlands—hence the name “surge plain.”

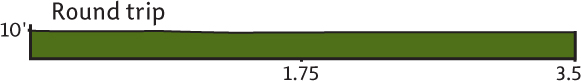

Continuing, you’ll soon pass a plant restoration area. Lined with a hedgerow of willows and alders, the trail skirts an active farm. At 1.75 miles you’ll arrive at a bench and slough overlook. Beyond this point the trail gets less use and may be a bit grassy. Carry on, traversing a marshy area, where copious birds—flycatchers, wrens, and warblers—will serenade you. At 3.5 miles you’ll come to the trail’s western end at a small parking area and a great overlook of the larger Blue Slough. Entertain thoughts about kayaking this inviting waterway before returning to your car.

Old pilings in Blue Slough at the end of the Chehalis Surge Plain Trail

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

On the north bank of the Chehalis River, not far from where you’ve hiked, is Friends Landing. This Trout Unlimited property includes a 1.7-mile wheelchair-accessible trail along the river, leading to a pond and through old growth.

Grays Harbor

Grays Harbor is Washington’s other great coastal estuary. With a surface area of 60,000 acres it rivals Willapa Bay in both size and ecological importance. But unlike its counterpart to the south, Grays Harbor has been heavily developed. While Willapa Bay sports very little human intrusion, no jetties, and contains thousands of acres of protected shoreline and tideflats, Grays Harbor is a study in contrast.

The eastern reaches of this estuary are highly industrialized. Three cities, Aberdeen, Hoquiam and Cosmopolis, sprawl where the Chehalis River drains into the estuary. These mill cities were once among the largest providers of forest products in the country. Past, sometimes unsustainable logging practices, coupled with rising globalization that favors cheaper imports, left these once-proud cities economically depressed. A century-plus of intense industrialization has also left Grays Harbor’s natural communities in a diminished state.

On the estuary’s western end, where it meets the Pacific Ocean, resort development has also compromised this great ecosystem. Fortunately, however, for hikers and nature lovers all is not lost. In recent years conservationists have been giving this great waterway some much-needed attention. The Grays Harbor Audubon Society has been protecting shoreline along North Bay near the mouth of the Humptulips River, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service established a 1500-acre national wildlife refuge at Bowerman Basin in 1990.

Grays Harbor is one of the most important staging areas on the entire Pacific Coast for shorebirds. One of the largest concentrations of western sandpipers, dunlins, and dowitchers south of Alaska can be observed here. Grays Harbor offers hikers a handful of other great wildlife-observing locales as well.

Hopefully this region will someday sport more protected areas, providing this important estuary with not only ecological recovery but perhaps economic recovery in the form of sustainable ecotourism.

|

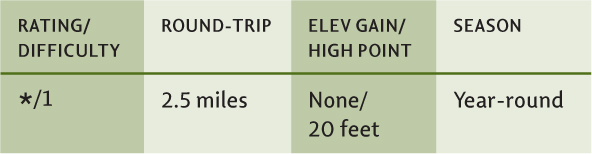

Johns River State Wildlife Area |

Map: USGS Hoquiam; Contact: Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Region 6 Office, Montesano, (360) 249-4628, http://wdfw.wa.gov/reg/region6.htm; Notes: Dogs must be leashed. Discover Pass required; Popular elk and bird hunting area; GPS: N 46 53.986, W 123 59.731

|

Hike on an old dike along the Johns River into an estuary teeming with birds and elk. The first half of the trail is wheelchair-accessible, offering an easy hike for all. |

GETTING THERE

From Aberdeen head west on State Route 105 for 12 miles. Pass the Markham Ocean Spray Plant. Immediately after crossing the Johns River Bridge, turn left onto Johns River Road. In 0.1 mile turn left onto Game Farm Road (signed “Public Fishing”), and in another 0.1 mile turn right into the trailhead parking area. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

Developed by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, this popular trail grants hikers and bird-watchers easy access to the 1500-acre Johns River State Wildlife Area. The first 0.6 mile is paved, providing wheelchair-bound hikers the opportunity to enjoy this wildlife-rich area. The pavement also guarantees that the trail won’t be muddy during the rainy season, which in Grays Harbor can sometimes be all year.

Hugging this main river of the Grays Harbor basin, the trail traverses an area nearly void of trees. A few lone Sitka spruce and hawthorns punctuate the grasses and reeds of the surrounding estuary. At pavement’s end is a blind, but quiet hikers shouldn’t need it to observe resident birds. Herons, grebes, terns, geese, and sandpipers are usually easily spotted along the way.

Continue on the now-grassy trail to reach the forest’s edge at 1 mile. Scan the reclaimed marshland on your right (west) for members of the resident elk herd. If the big beasties themselves aren’t present, plenty of evidence of their passing most certainly will be. Continue another 0.25 mile into the forest to where the trail begins to climb from the floodplain. You can go farther another 0.25 mile to the trail’s end on Johns River Road, but in scrappy forest it’s hardly worth it. Instead, retrace your steps and explore the diked pasture near the bird blind.

Tide is in on the Johns River—Johns River Wildlife Refuge

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

About 2 miles of wooded roads within the wildlife area can be walked on the opposite side of the river. Nearby Westport Lighthouse State Park contains a 1.3-mile paved trail along the Pacific.

|

Damon Point State Park |

Maps: USGS Point Brown, USGS Westport; Contact: Ocean City State Park, (360) 289-3553, infocent@parks.wa.gov, www.parks.wa.gov; Notes: Dogs must be leashed. Discover Pass required; Snowy plover closure of Damon Point interior Mar 15–Aug 31. Park sustained serious flood damage in December 2007; consult ranger for current status. GPS: N 46 56.774, W 124 07.895

|

Once an island, now a spit, Damon Point keeps growing thanks to sand accretion (the opposite of erosion). Hike around this protruding land mass for sweeping views that include Mount Rainier and the snowy Olympic Mountains. Observe scores of shorebirds (including endangered snowy plovers), harbor seals, and the remains of a notorious ocean liner. Best of all, enjoy 4 miles of vehicle-free beaches. |

A hiker reads about the endangered snowy plover before setting out for a hike on Damon Point.

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam head west for 16 miles on State Route 109 to its junction with SR 115. Continue south 2.5 miles on SR 115 to the resort town of Ocean Shores. Proceed south on Point Brown Avenue. In 0.75 mile come to a four-way junction, and continue straight. In 4.5 miles the road bends right, becoming Discovery Avenue. In another 0.25 mile it becomes Marine View Drive. Locate a sign for Damon Point State Park, directing you to turn left onto Protection Island Road. Drive 0.1 mile to the park entrance and trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

Some parks are designed by humans, but nature seems to have had a hand in Damon Point’s fate. Named for A. O. Damon, who settled here in 1861, the point has grown to connect with Protection Island, creating a spit 1 mile long and 0.5 mile wide. Washington State Parks then built a road up the middle of the spit. Then nature stepped in, sending a storm to sever the road, providing an outlet for a newly formed pond. Will an island reemerge? Maybe. In the meantime you better get hiking, or you might need a kayak for future visits.

Best hiked at low tide, the trail starts by heading to the bayside beach (to left of closed peninsula road). Turn east for your 4-mile journey around the 61-acre spit. In 0.5 mile you’ll come to a creek. In winter, plan on getting your feet wet crossing it. Several winters ago storms washed away the dunes here to reveal a ship hull. It was the S.S. Catala, shipwrecked in 1965. The Catala had a colorful history, from transporting loggers and miners, to housing world’s fair visitors, to onboard offerings of entertaining vices. Hikers were able to explore it until state officials removed it because it was leaking toxins into the beach.

Round the first point and come to a nice beach area. On your right is the former picnic area being reclaimed by vegetation, both endemic and invasive. At 2.5 miles you’ll round the second point, where you’ll be greeted by the fury of coastal winds. Enjoy good views of Westport across the way. Make your way back to the trailhead along a wide beach framed with high rolling dunes. Bald eagles frequently perch on big beached logs lining this stretch of beach. At 4 miles a small trail cuts back to the parking lot.

|

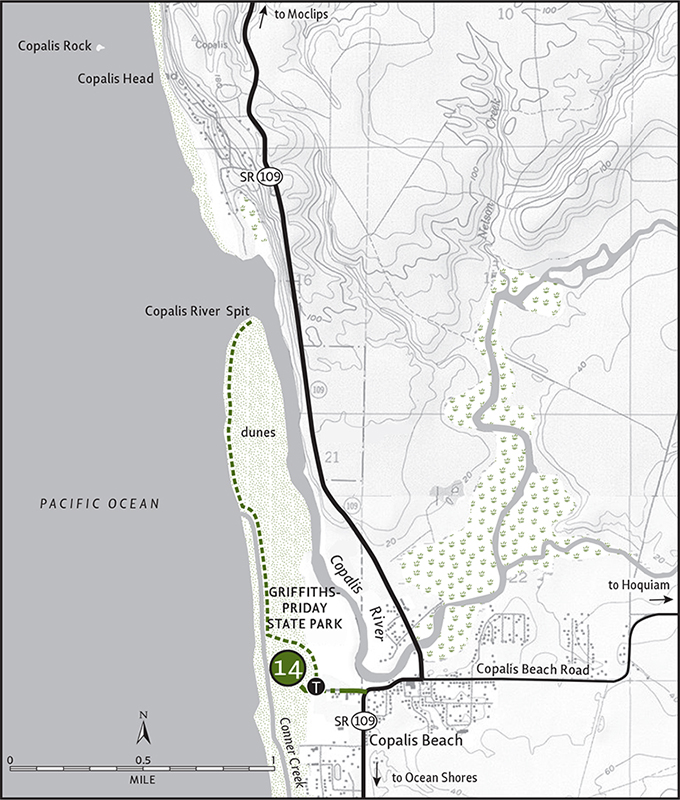

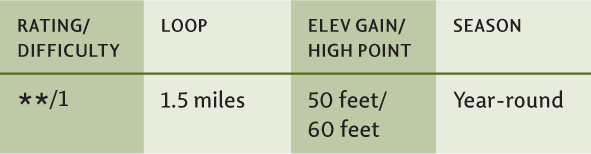

Copalis River Spit |

Maps: USGS Copalis Beach, USGS Moclips; Contact: Griffiths-Priday State Park, (360) 289-3553, infocent@parks.wa.gov, www.parks.wa.gov; Notes: Dogs must be leashed; Discover Pass required; GPS: N 47 06.882, W 124 10.670

|

Enjoy vehicle-free beach hiking on a quiet spit teeming with birdlife. Located just a few miles from bustling Ocean Shores, the beaches of Griffiths-Priday State Park are often deserted. |

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam head west on State Route 109 for 21 miles to the community of Copalis Beach. At the Green Lantern Tavern turn left onto Benner Road, proceeding 0.2 mile to the park entrance and trailhead. Water and restrooms available.

ON THE TRAIL

One of the quietest stretches of beach south of the Quinault Indian Reservation, the Copalis River Spit makes for a good hike any time of year. Within this 365-acre state park, roads, condos, and other human intrusions are absent.

It used to be a 0.25-mile hike to the beach, but in the late 1990s Conner Creek changed course, extending its route to the sea by nearly 0.5 mile. Now a 0.75-mile hike is required to get to the surf. But what a three quarters of a mile it is! The trail goes through one of the largest dune complexes in the state. Admire the dunes from the trail, though, so as not to disturb the myriad of birds that nest here. Perhaps some day snowy plovers will return.

Follow the wide path through the dunes, eventually coming to a point above Conner Creek. Continue northward to where the creek turns to empty into the Pacific, and you too are free to reach the sea. On a wide, hard-packed sandy beach, hike 1.25 miles north to the tip of the spit. Copalis Rock, a large sea stack and part of the Copalis National Wildlife Refuge, is visible in the distance.

A pair of hikers fight the wind in hiking across dunes on their way to Copalis Spit.

The spit is often littered with sand dollars, half sand dollars, and quarter sand dollars when the tide is out. Scan overhanging trees along the north bank for eagles and osprey. At low tide it’s possible to hike along the ocean side of the river for a short ways. Deep mud will let you know when it’s time to turn around.

Black Hills: Capitol State Forest

Rising to the southwest of Olympia are the heavily forested Black Hills. Like the Willapa Hills in the state’s southwestern corner, the Black Hills are composed of rolling and gentle peaks. The highest summits are just over 2600 feet. But the relief is prominent due to close proximity to the Puget Sound Basin and the Chehalis River valley. Shrouded in green and stroked with smooth contours, these hills look like they belong in Virginia or Pennsylvania.

But they’re a unique part of the Washington landscape. Consisting of underlying basalt, the Black Hills actually take their name from a Native American term, klahle, describing the dark shadows cast by the ever-changing cloud patterns blown in from the coast. Fires and widespread logging swept through the area in the early part of the twentieth century. During the Great Depression, the state authorized repurchase of the cutover lands.

Today, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources manages over 90,000 acres of the Black Hills as the Capitol State Forest. Primarily a working forest providing a steady stream of timber (converted to income for the state’s schools), since 1955 the forest has also been managed for recreation. Over 100 miles of trails traverse the Capitol State Forest. And while many of these are multiuse, the forest provides plenty of motor-free miles for hiking. Actually, all trails are motor-free (and horse-free) from November 1 to March 31.

As the Olympia–South Sound area continues to grow, the Capitol Forest’s importance as a backyard wilderness providing clean water, wildlife habitat, and easily accessible recreation also grows. While this forest may lack the ruggedness of other areas in this book, it offers plenty of surprises—from sweeping views to quiet valleys, plenty of history, and a very well-maintained and cared-for trail system.

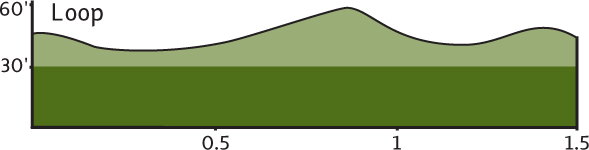

|

McLane Creek |

Maps: USGS Little Rock, Capitol State Forest DNR map; Contact: Department of Natural Resources, Pacific Cascade Region, (360) 577-2025, pacific-cascade-region@wadnr.gov, www.dnr.wa.gov; Notes: Dogs must be leashed. Discover Pass required; Trail closed at dusk; GPS: N 47 00.046, W 123 00.252

|

Hikers of all ages, especially children, will love this easy loop, one of the finest nature trails in Western Washington. On good tread and boardwalk this trail takes you on an up-front and personal journey along McLane Creek and an adjacent beaver pond. Plenty of birds and critters will captivate you along the way. |

GETTING THERE

From Olympia head west on US 101 for 2 miles, taking the Black Lake Boulevard exit. Proceed left (south) on Black Lake Boulevard. In 3.5 miles the road turns right (west), becoming 62nd Avenue. Continue another 0.7 mile to a stop sign. Turn right on Delphi Road. In 0.5 mile turn left into the McLane Creek Demonstration Forest. Reach the trailhead in 0.4 mile. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

The Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) should be commended on this trail. It was clearly developed with environmental sensitivities and with the intent of making it easy for people to connect with nature. If the DNR can only bring some of this same care to other parts of the Capitol State Forest, the possibilities are great.

McClane Creek’s Beaver Pond is a good place for observing birds.

The McLane Creek Nature Trail consists of a 1.1-mile outer loop and a 0.3-mile connector trail. My recommendation: do a figure-eight and take your sweet time. With interpretive plaques and observation decks along the way, McLane Creek is meant to be savored. Time of day and season will dictate which critters you might observe. Keep your senses keen and you should see plenty anytime you visit.

The trail starts off by skirting a large beaver pond. In springtime the wetland is transformed into a musical marsh thanks to a chorus of blackbirds and an ensemble of tree frogs performing regularly. Cattails and pond lilies punctuate the nutrient-rich wetland. Soon you’ll encounter the shortcut trail. Once part of the Mud Bay Logging Company’s rail line, this trail offers more good views of the beaver pond and perhaps a peek of the beavers themselves.

The main trail darts into a dark and gloomy forest of cedar, hemlock, giant maples and over-your-head devil’s club. Heading along McLane Creek and twice over it, look for spawning salmon come fall. The trail passes through a hemlock tunnel that children will want to pass through again and again. Next, traverse a skunk cabbage patch before returning to the beaver pond. Take the shortcut trail right or head left to loop around the willow-, alder-, and cascara-lined wetland, returning to the trailhead.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

An upper parking lot 0.25 mile from the trailhead provides access to a short loop trail in the Centennial Demonstration Forest.

|

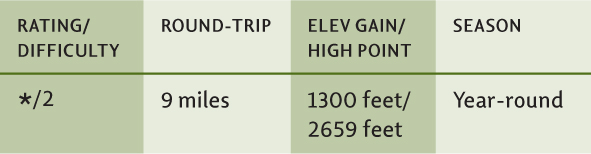

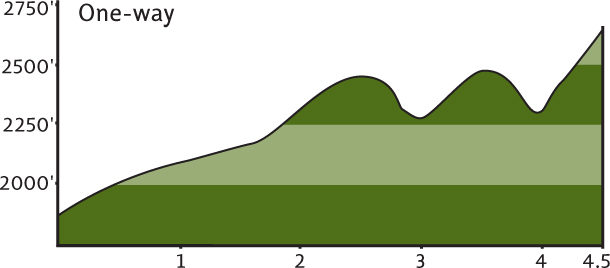

Capitol Peak |

Maps: USGS Capitol Peak, Capitol State Forest DNR map; Contact: Department of Natural Resources, Pacific Cascade Region, (360) 577-2025, pacific-cascade-region@wadnr.gov, www.dnr.wa.gov; Notes: Discover Pass required; Roads are poorly marked, forest map essential; GPS: N 46. 56.909, W 123 11.641

Come for the views: they’re quite extensive, from Rainier to the Pacific. Come for the trail: it’s well built, not heavily used, and it runs a high ridge for miles. Clad in communication towers, however, the peak may be the highest point on this hike, but it’s certainly not the highlight.

GETTING THERE

From Olympia head west on US 101 for 2 miles, taking the Black Lake Boulevard exit. Proceed south on Black Lake Boulevard. In 3.5 miles the road turns west, becoming 62nd Avenue. Continue another 0.7 mile to a stop sign. Turn left on Delphi Road, continuing for 2.2 miles. Turn right on Waddell Creek Road and in 2.7 miles enter the Capitol State Forest. Bear right onto Sherman Valley Road, and in 1.5 miles turn left onto the C Line. Follow this mostly gravel, sometimes paved road for 7 miles to a major junction (just beyond a quarry). Turn left, continuing on the C Line for 1.5 miles to the seriously neglected Wedekind Picnic Area. Park here. The trail starts on the west side of the C Line.

ON THE TRAIL

Hike this trail and dream of the possibilities for the Capitol State Forest. There’s no reason that this 90,000-acre piece of the public domain can’t be Olympia’s Tiger Mountain. But the area has been long plagued by illegal dumping, shooting, and other problems, causing hikers to shy away. Motorized groups have adopted trails on their half of the forest, and equestrian groups work on nonmotorized trails, but where are the hiking groups? If hikers begin taking more of a vested interest in this forest—volunteering on trail crews, cleanups, and watches—the problems will dissipate. Capitol Forest is getting better, but it’s going to take a lot of work from dedicated citizens and some better funding and management from the state to transform this parcel into what it should be—a prime hiking destination.

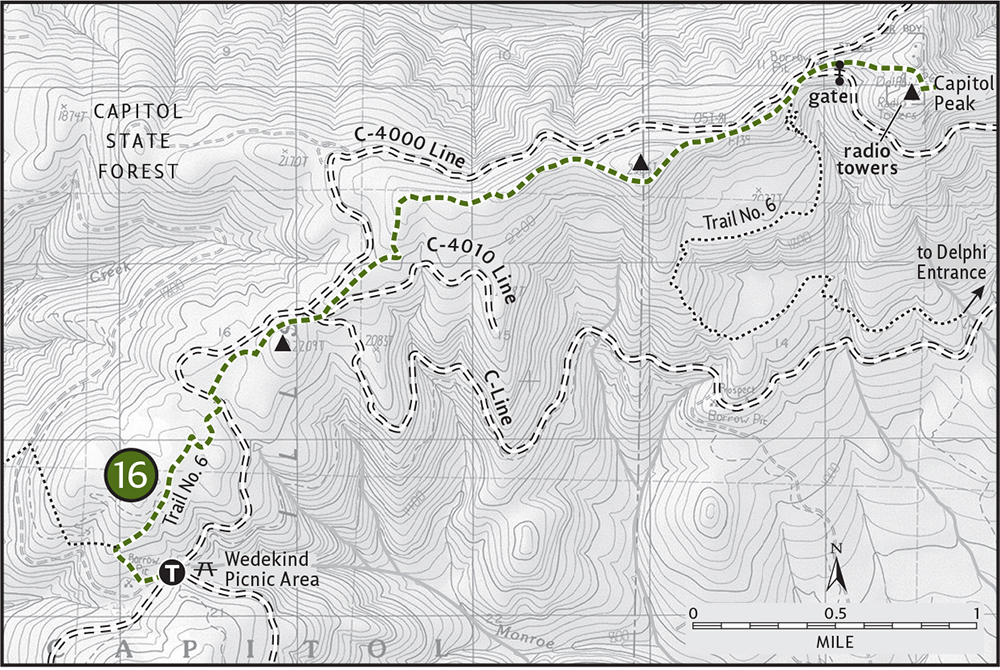

Contemplate this vision as you hike along the Capitol Crest, the rooftop of the Black Hills. From your high start (1880 feet) hike Trail No. 30 for about 0.3 mile to a junction. Turn right onto Trail No. 6, the Green Line. On very good tread begin a rolling ridgetop romp to Capitol Peak. After about 1.3 miles, cross the C Line that you drove in on. Alternating between fir forests lined with oxalis (pretty white blooms in late spring) and raspberry-cloaked “balds” reminiscent of the southern Appalachians, the trail is a pure delight to travel. Teaser views of the Cascades, Olympics, and Willapa Hills are had along the way.

At 2 miles you’ll cross the C Line again, this time at its junction with the C-4000 Line on the left and the C-4010 Line on the right. The trail resumes a few hundred feet up the C-4010. Continue through more fir forests and shrubby openings. After 3 miles pass an old hitching point and then climb a little and drop a little through open forest with more peek-a-boo views. At 3.5 miles, cross another road. The trail, now paralleling two roads, climbs a small knoll above them only to descend where they meet up. Here, at 4 miles from your start, Trail No. 6 heads east, rapidly descending off the ridge.

Nice signing along the trail heading to Capitol Peak

This is the end of your trail hike. To access Capitol Peak, walk the road north a few hundred feet to a three-way junction. Take the gated middle road and climb steeply to the 2659-foot peak, second-highest summit in the Black Hills. Under a skyline of communication towers, reach out to sweeping views. To the east are the Cascades, from Mounts Baker to Adams. Rainier is directly in front of you, rising above the Bald Hills. Extending to the north are the finger peninsulas and inlets of the South Sound. To the west, the Satsop Towers rise above the Chehalis Valley, while the Olympics and Pacific Ocean can be seen in the distance. Soak it all in and retrace your steps.

|

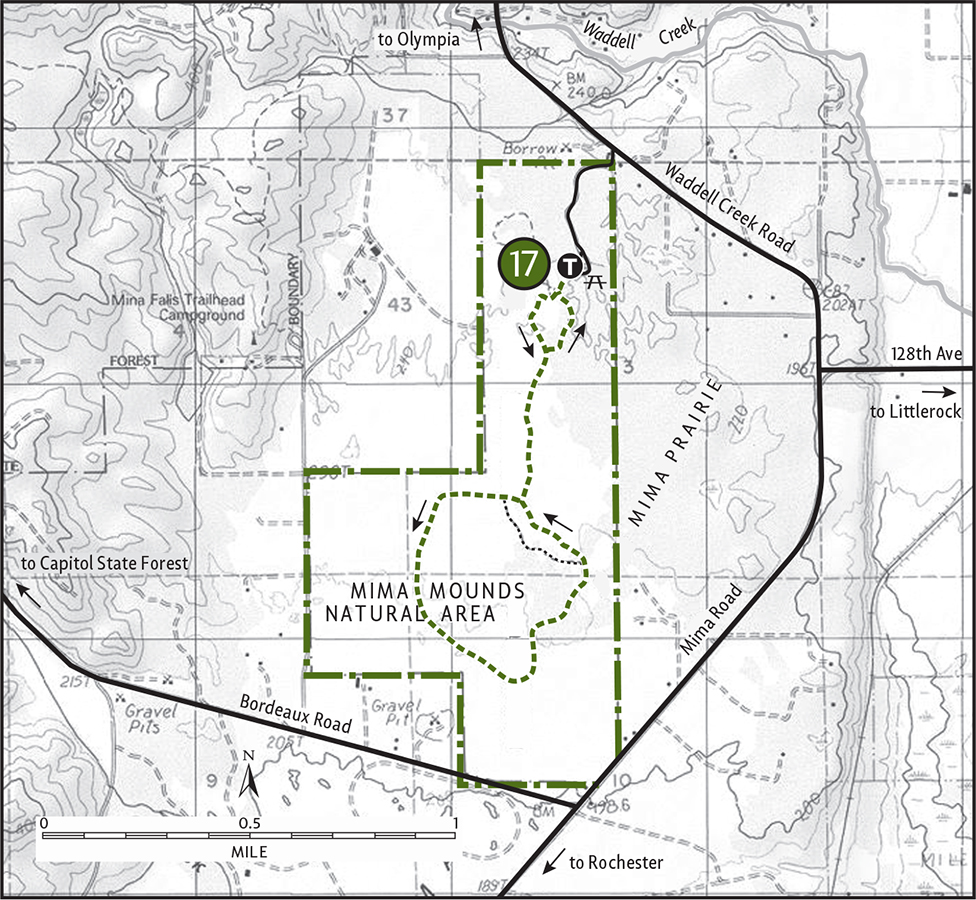

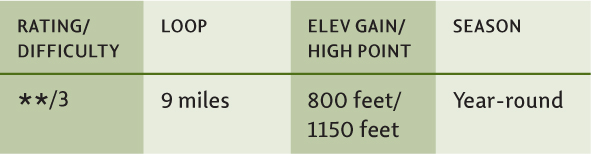

Mima Mounds |

Maps: USGS Little Rock, Capitol State Forest DNR map; Contact: Department of Natural Resources, Pacific Cascade Region, (360) 577-2025, pacific-cascade-region@wadnr.gov, www.dnr.wa.gov; Notes: Dogs prohibited. Discover Pass required; Trail closed at dusk; GPS: N 46 54.307, W 123 02.879

|

Hike through a landscape that almost appears lunar (except for the vegetation of course). Weave in and out and even over a few of the hundreds of 4-to 6-foot mounds scattered across this Thurston County prairie. How did they get here? Who or what made them? You’ll most certainly be pondering these thoughts while hiking through this geologically intriguing landscape. |

Wide open spaces in the prairie that houses the Mima Mounds

GETTING THERE

From Olympia take I-5 south to exit 95. Follow Maytown Road west for 3 miles to Littlerock. At a stop sign proceed forward (west) on Littlerock Road, which soon turns left (south). Bear right here onto 128th Avenue (signed for the Capitol State Forest). In 0.7 mile come to a T intersection. Turn right onto Waddell Creek Road and drive 0.8 mile. At a sign announcing “Mima Mounds Natural Area,” turn left and reach the trailhead in 0.4 mile. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

Most visitors to this National Natural Landmark just visit the observation deck and maybe walk the 0.5-mile paved nature loop. But to really appreciate the mysterious nature of the Mima Mounds, take to the trail that loops around this 445-acre preserve. By all means head for the observation deck first to get a look at this bizarre arrangement of “earthen hay bales.” Scientists continue to debate the mounds’ origins. Was it the thawing and freezing during the last ice age that caused the land to buckle? Or perhaps pocket gophers were at work, having since moved on to haunt golf courses?

Walk the paved path for 0.3 mile to find the trailhead for the prairie loop trail. Once on a soft-surface path, head into the heart of the mounds. The surrounding forest has encroached on the prairie—invasive plants too, like the dreaded Scotch broom. The Washington State Department of Natural Resources and volunteers are trying to restore the prairie to the way it appeared when Native peoples periodically set fires to them, keeping the vegetation in check.

At 0.65 mile pass an old fence line, a remnant of early farming on the mounds. At 0.75 mile come to a junction, and turn right for the loop. Soon pass another junction, a shorter loop option. Continue right, hiking the periphery of the preserve. Enjoy views of Mounts Rainier and St. Helens towering in the distance. At 2.1 miles close the loop and retrace your steps back to the trailhead. The Mima Mounds are exceptionally beautiful in April and May, when prairie flowers such as blue violet, buttercup, and camas paint them in dazzling colors.

|

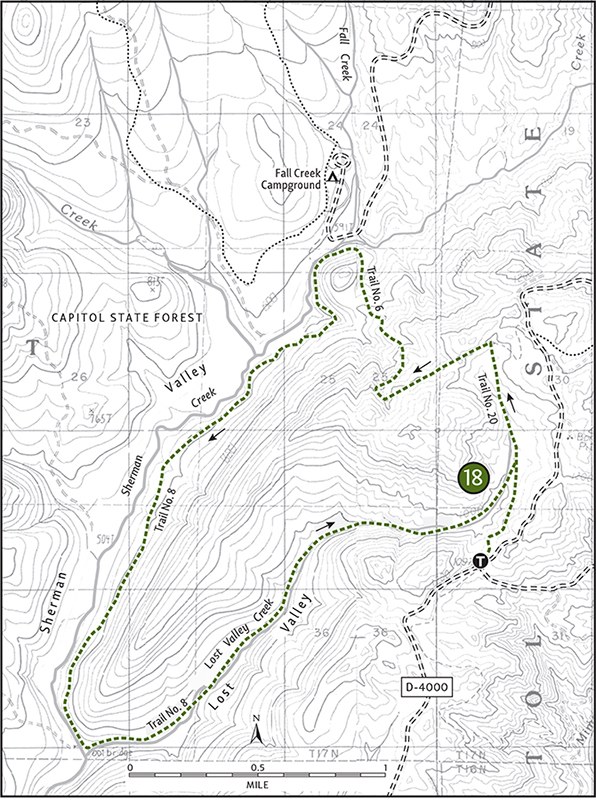

Sherman Creek |

Maps: USGS Little Rock, Capitol State Forest DNR map; Contact: Department of Natural Resources, Pacific Cascade Region, (360) 577-2025, pacific-cascade-region@wadnr.gov, www.dnr.wa.gov; Notes: Discover Pass required; GPS: N 46 55.550, W 123 06.752

|

One of the best hiking options in the 90,000-acre Capitol State Forest, the Sherman Creek Loop travels up and down two visually appealing valleys. No grand views or grand forest here—just miles of tranquil woods and creekside walking and some historic relics from the golden age of logging. Equestrians and mountain bikers share these trails, but crowding isn’t an issue. Come during the week and have this place to yourself. |

GETTING THERE

From Olympia take I-5 south to exit 95. Follow Maytown Road west for 3 miles to the community of Littlerock. At a stop sign proceed forward (west) on Littlerock Road, which soon turns left (south). Bear right here onto 128th Avenue (signed for the Capitol State Forest). In 0.7 mile come to a T intersection. Turn left on Mima Road and after 1.5 miles turn right (west) onto Bordeaux Road. Follow this good paved road for 3.5 miles to a Y intersection. Bear right, following the D Line for 0.6 mile to a four-way intersection on a hill crest. Turn right onto the D-4000 Line and follow this good gravel road for 2 miles to its junction with the D-4400 Line, where you’ll find the trailhead. Park on the wide shoulder near the junction.

ON THE TRAIL

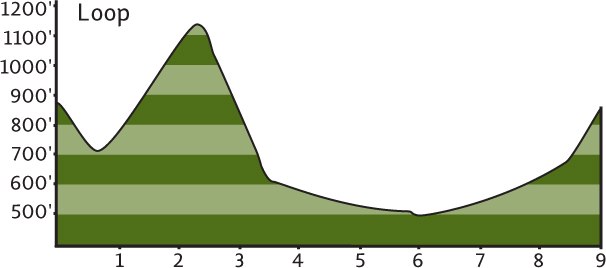

This loop begins by following the Mima Porter Trail (Trail No. 8) for 0.4 mile down to a junction in the Lost Valley Creek. The trail on your left is your return route. These trails are in excellent shape thanks to the volunteer work of the Backcountry Horsemen (and women) of Washington.

Lush fern growth along tranquil Sherman Creek

Head right on Trail No. 20. Climbing gradually, pass a few big firs, a lot of skunk cabbage, and an active beaver pond. In 1.4 miles come to a junction with Trail No. 6, the Green Line. Turn left and follow this good trail. Climb a bit more, and after crossing a logging road enter a mature second-growth forest. Begin a long descent into the Sherman Creek valley. At 2.6 miles emerge from the forest to cross a recent cut. Notice the temperature change. Notice Capitol Peak and Larch Mountain in front of you. Notice, too, that there are no larches on Larch Mountain. Hmm.

At 3.25 miles reach the lovely Sherman Creek valley, where you’ll come to another trail junction. The trail right crosses the creek (bridge out as of summer 2006) and heads to the Fall Creek trailhead and onward to the Capitol Crest. You’ll want to continue left on Trail No. 8 for an enjoyable journey down the valley. Plenty of lunch spots along the way will entice you to take a break.

After about 3 miles of hiking along the creek you’ll come to an old trail junction. There used to be a trailhead on the other side of the creek, but it and the road no longer exist. This decommissioning has helped return a little solitude to this region. The trail now leaves Sherman Creek to follow Lost Valley Creek upstream. This is the best part of the loop. Under a canopy of moss-draped alders and big cedars, the trail uses an old logging railroad bed. After 1 mile of heading up Lost Valley Creek, look for trestle remnants. Look, too, along the creek for relics from the old logging days. Broken bricks and porcelain plates litter the area. Be sure to leave these artifacts for others to enjoy.

Hike about 1.5 more miles upstream back to the junction with Trail No. 20. Turn right and follow Trail No. 8 for 0.4 mile back to your vehicle.

BUILDING A DIFFERENT CAPITOL IN OLYMPIA

The Capitol State Forest has long been a place where Olympia hikers come to hike. But soon they’ll be able to hike to the Capitol State Forest. A so-called Capitol-to-Capitol trail is being developed to link the city with the forest. Starting at the state capitol campus, the new trail will thread together local schools, including the Evergreen State College, and city parks to reach the sprawling state forest.

Overseen by the Washington State Department of Transportation, the trail has long been advocated by various community groups. School groups, local volunteers, and inmates from the Cedar Creek Corrections Center (located within the state forest) have already developed sections of the trail. And while it will be years before this project is complete, it is a major step in the right direction—providing greenbelts in the Olympia region.

As suburbia continues to sprawl across the countryside and the average American’s waistline continues to sprawl as well, greenbelt trails like the Capitol-to-Capitol are all the more important for the health of our communities and their residents. These trails connect parks and preserves and provide people places to exercise close to where they live. As fuel prices continue to soar and open space continues to dwindle, places like the Capitol State Forest will only grow in importance. Making them more accessible should be a priority for both government and community leaders.