olympic peninsula: northeast

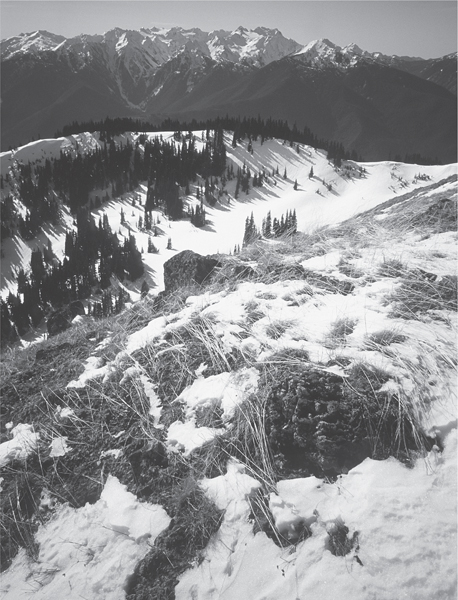

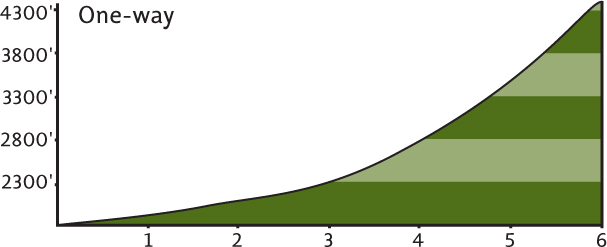

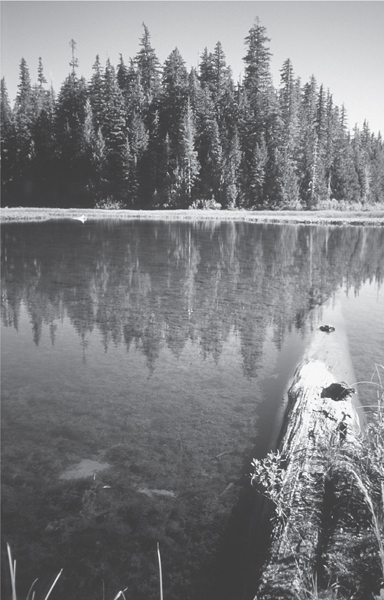

Placid Deer Lake above the Sol Duc Valley

olympic peninsula: northeast

Placid Deer Lake above the Sol Duc Valley

Strait of Juan de Fuca

The portal to Puget Sound, the 100-mile-long Strait of Juan de Fuca acts as a transition zone between the Pacific Ocean and Washington’s great inland waterway. And like all transition zones, diversity is legion. From dry Doug-fir forests in the rain shadow to dew-dripping salty spruce groves at its mouth, Juan de Fuca’s landscapes change radically and dramatically moving from east to west. And while the mood is always maritime, alpine scenery adorns the backdrop. The snowcapped Cascade peaks or Vancouver Island’s rugged ranges are always in view across this long arm of the Pacific.

Though the strait is populated along its more gentle eastern fringes, its western reaches are wild and sparsely settled. But this waterway is a busy place, a super highway for thousands of tankers and vessels plying their way to ports in Victoria, Vancouver, Seattle, Tacoma, and a handful of other destinations.

On the trails and beaches of Juan de Fuca, however, it is possible to seek out quieter waters. The western reaches are lightly visited, while winter casts a quiet shadow upon the entire region. And year-round, the hiking is always rewarding.

|

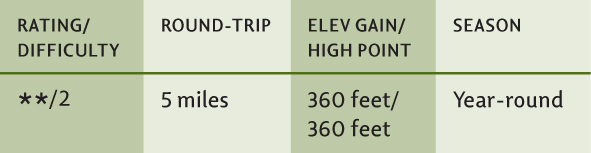

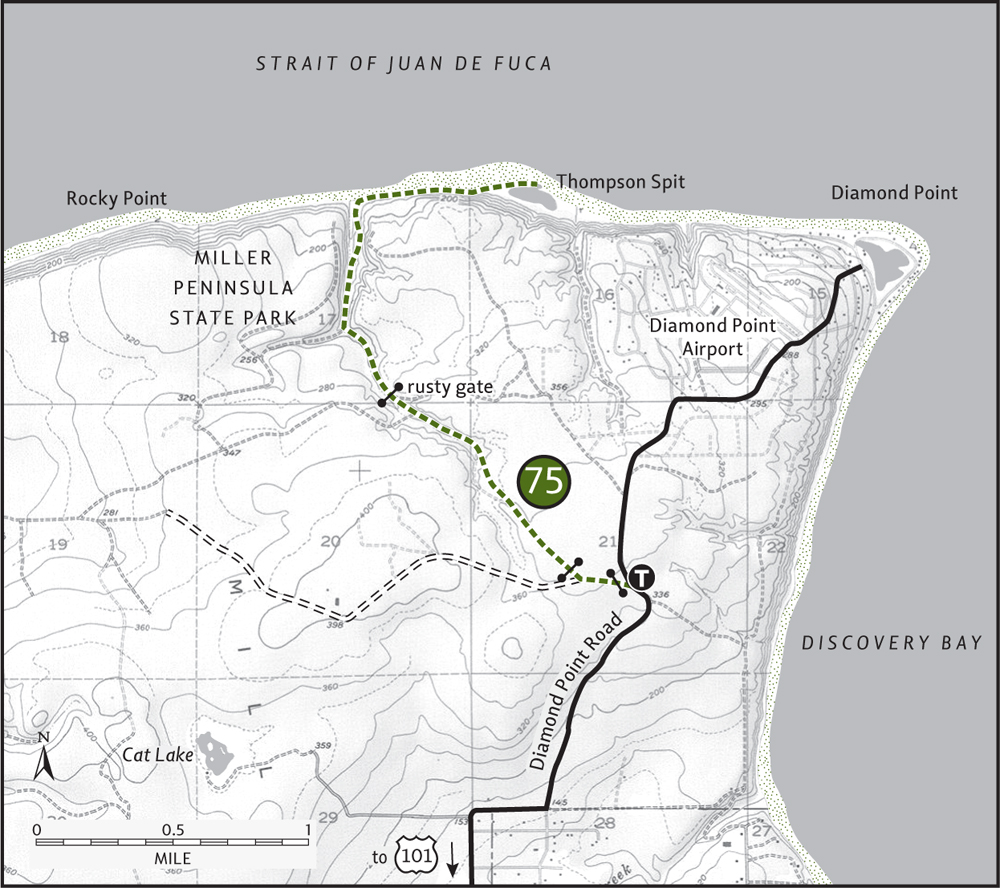

Miller Peninsula and Thompson Spit |

Map: USGS Gardiner; Contact: Sequim Bay State Park, (360) 683-4235, infocent@parks.wa.gov, www.parks.wa.gov; Notes: Restricted parking, don’t block Northwest Technical Industries access road. State park development underway, hiking routes may change; GPS:N 48 04.659, W 122 56.542

|

Explore a cool lush ravine that leads to a remote beach on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Walk along the shore under towering bluffs to a spit littered with drift logs and watched over by a battalion of eagles. Take in clear views of Protection Island, a bird sanctuary at the mouth of Puget Sound, difficult to see from most other shoreline points. Welcome to the Miller Peninsula, destined to become Washington’s next grand state park. |

GETTING THERE

From the west end of the Hood Canal Bridge, drive State Route 104 to its end and veer north onto US 101. Continue on US 101 for 11 miles to the Clallam–Jefferson County line near milepost 275. (From Sequim head east 10 miles on US 101.) Turn right (north) on Diamond Point Road (signed “Airport”), proceeding 2.2 miles. Where the road makes a sharp left turn, park in a small pullout on the right. The hike begins on a gated road on the opposite side of the road—use caution crossing.

ON THE TRAIL

Once considered for a nuclear power plant, and once almost sold to a Japanese company for development into a golf resort, this former Washington State Department of Natural Resources timberland and magnificent piece of coastal property has not always been revered by state officials. But Washington’s citizens have, and the property was transferred to the state parks division. After sitting idle for 15 years the state planned to have the park’s facilities developed in time for the agency’s centennial in 2013. Meanwhile, the Washington Trails Association has helped clear a trail through the property so you can start exploring and get a preview of just what this 2800-acre prime piece of public land has to offer.

Start your sneak peek by walking up the Northwest Technical Industries access road for 0.2 mile to an old gated road on your right. Follow this nice woodlands byway through a thick stand of second growth. After 1 mile come to a junction with another old road and head right. Immediately come to another road junction and go left.

Shortly afterward approach an old rusty gate (at 1.3 miles). Pass it, descending into a rhododendron-lined gully. Soon you’ll notice a sign indicating the way to the beach. Head right on a refurbished trail compliments of the WTA.

Wind your way 0.4 mile through a lush narrow ravine graced with remnant old-growth fir and cedar. Rays of light begin penetrating the forest, and the sound of the surf grows louder. At 1.75 miles from the trailhead, reach a long and deserted but wildly beautiful beach. If the tide is high, plop your bum on a driftwood log and let the surf serenade you. If the tide is out, walk the cobbled beach right (east) under a fortress of high bluffs capped in thick forest.

Protection Island’s chalky bluffs shine across choppy waters. Mount Baker’s snowy cone rises above the San Juan Islands. After 0.75 mile of beach strolling, come to log-littered Thompson Spit and its bird-rich lagoon. Eagles, buffleheads, geese, herons, and blackbirds go about their business in the brackish waters, while oystercatchers and harlequin ducks ply the shoreline. Stay for a while, but give yourself enough time to return before the tide does. Contemplate and rejoice in the new trails and camping facilities this emerging state park will soon provide.

A WTA work crew constructs a new trail at Miller Peninsula State Park.

|

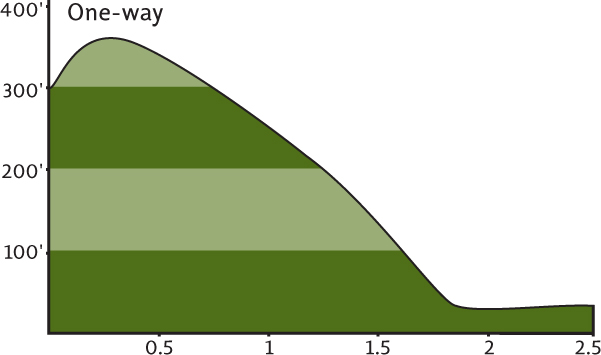

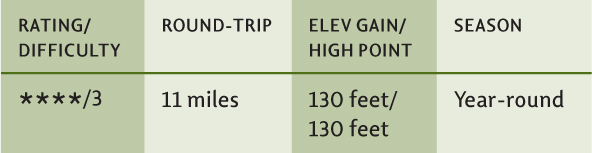

Dungeness Spit |

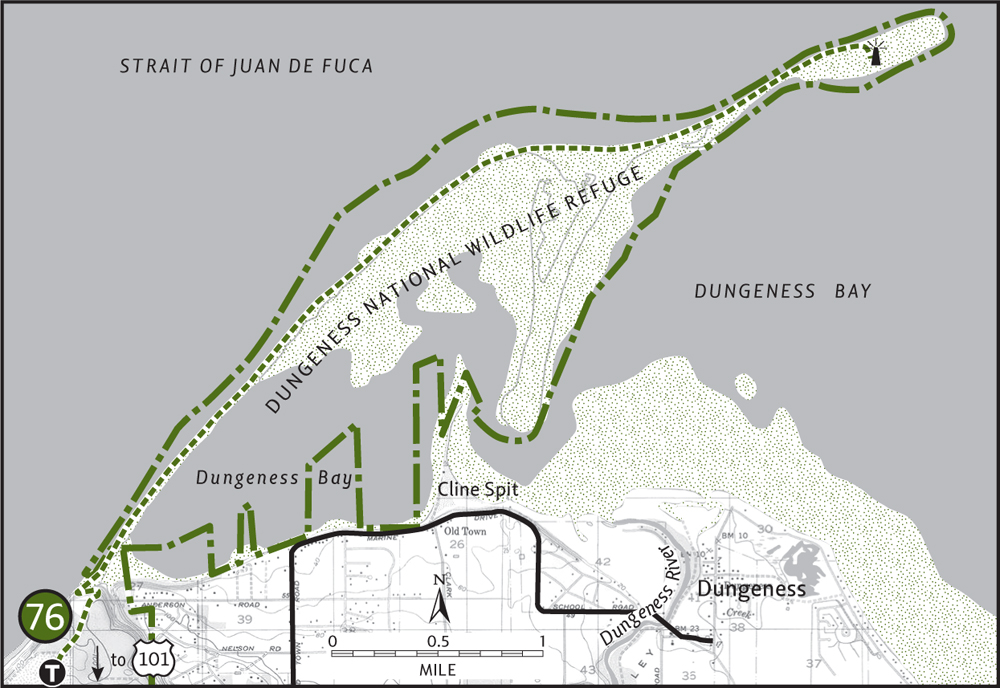

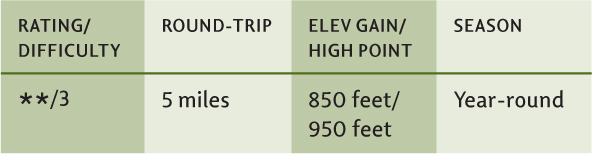

Maps: USGS Dungeness, refuge maps available at trailhead; Contact: Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge, (360) 457-8451, www.fws.gov/pacific/refuges/field/wa_dungeness.htm; Notes: $3 per family entry fee (Golden Eagle Pass accepted). Closed at sunset. Dogs prohibited. Hike may be difficult in highest tides; GPS: N 48 08.480, W 123 11.395

|

No need to head all the way to the Pacific if it’s a good beach hike you seek. One of Washington’s best saltwater strolls is along its “north coast,” the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Actually, this hike heads directly into the strait on the longest coastal spit in the continental United States. A narrow strip of sand, dune, and beached logs, the Dungeness Spit protrudes over 5 miles straight into the strait. Prone to breaching during storms, the spit is also resilient and well-established—and well-hiked and loved by those who explore it. |

GETTING THERE

From Sequim head west on US 101 for 5 miles. (From Port Angeles drive east for 12 miles.) Turn right (north) at milepost 260 onto oddly named Kitchen-Dick Road. At 3.3 miles, Kitchen-Dick sharply turns right, becoming Lotzgesell Road. In another 0.25 mile, turn left on Voice of America Road (signed “Dungeness National Wildlife Refuge, Dungeness Recreation Area”). Proceed through the Clallam County park and campground, and in 1 mile come to the trailhead. Water and restrooms available.

ON THE TRAIL

The Dungeness Spit was formed by wind and water currents that forced river silt and glacial till to arch into the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Over the centuries the spit has grown to over 5 miles. You can hike all the way to the tip, where a lighthouse has been keeping guard since 1857. The extreme tip, however, like the Dungeness Bay side of the spit, is closed to public entry to protect important wildlife habitat. Because the spit is protected and managed as a wildlife refuge, many recreational activities are restricted. Please respect areas closed to public visitation.

Try to do this hike during low tide for easier walking. Lying within the Olympic rain shadow, the spit receives less than 20 inches of rainfall annually, making it a great winter destination when surrounding areas are socked in. Pack your binoculars too, as the bird-watching is supreme. Over 250 species have been recorded on the spit and in Dungeness Bay, including many that are endangered or threatened. Marbled murrelets, harlequin ducks, and snowy plovers frequent the area.

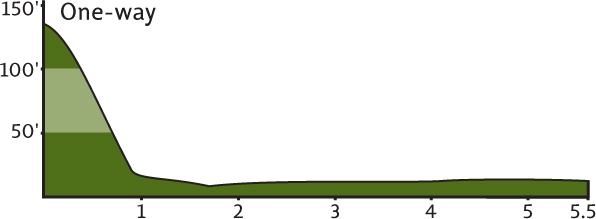

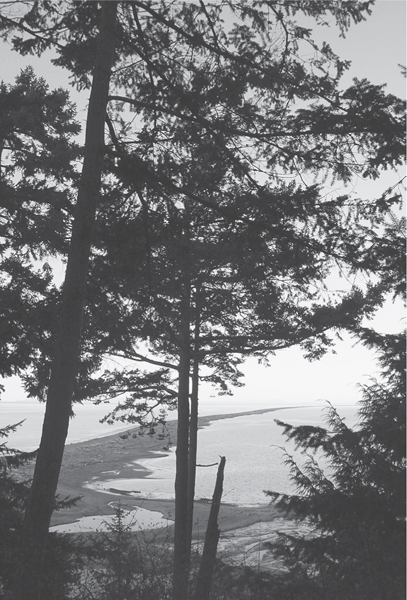

Follow the refuge trail 0.5 mile through cool maritime forest. Before descending to the beach, take in sweeping views of the spit from an overlook. Now drop 100 feet, emerging at the base of tall bluffs and at the start of the spit. It’s a straightforward hike to the lighthouse. Pack plenty of water and sunscreen. If the 11-mile round trip seems daunting, any distance hiked along the spit will be rewarding.

If you head south from the trail, you can wander for over a mile on oft-deserted beaches under golden bluffs. Mount Angeles hovering in the distance may very well lure you this way. No matter which way you venture, expect some of the best beach hiking around.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

The 630-acre wildlife refuge borders a 216-acre Clallam County park that contains developed campsites with awesome views. A 1-mile trail along a high bluff weaves through the park and makes for a great sunset hike.

Approaching Dungeness Spit from bluff above

|

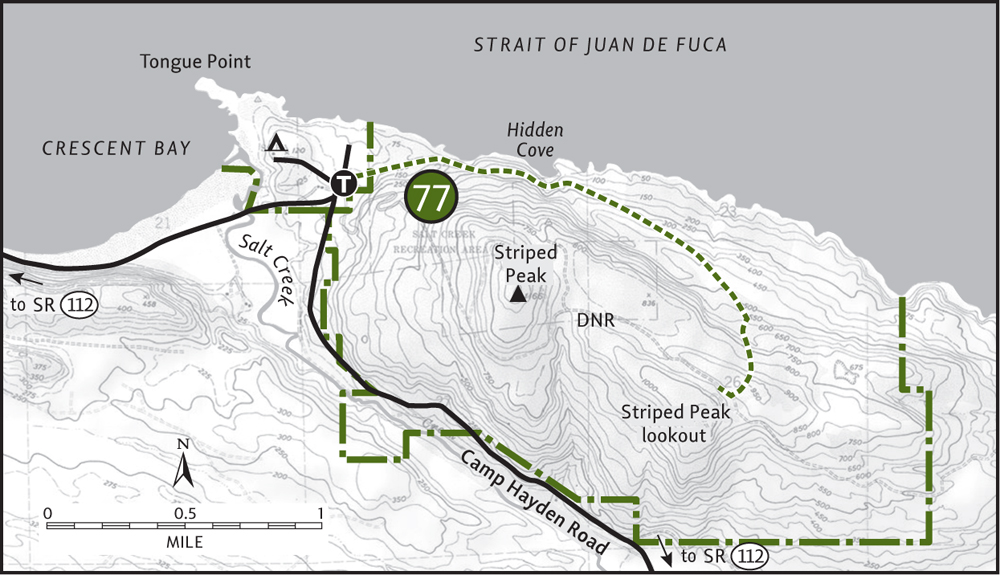

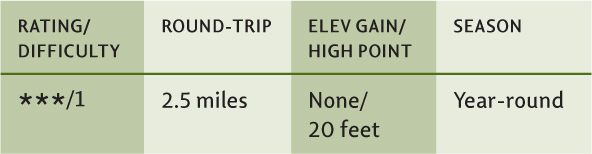

Striped Peak |

Map: Green Trails Joyce No. 102; Contact: Salt Creek County Park, (360) 928-3441, ccpsc@olypen.com, www.clallam.net/CountyParks/html/parks_saltcreek.htm; GPS: N 48 09.731, W 123 41.914

|

Two adventures in one await you at Striped Peak. First, hike to a 1000-foot peak rising above the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Watch liners and vessels ply this passageway connecting Puget Sound to the Pacific against a backdrop of craggy peaks on Canada’s Vancouver Island. Then head directly to the strait to explore a series of tide pools up close. Hike a steep trail down to a remote cliff-enclosed cove, or leisurely wander across a sandy beach on a picturesque bay. |

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles follow US 101 west for 5 miles to State Route 112. Turn right on SR 112, heading west for just over 7 miles. Turn right (north) onto Camp Hayden Road, following it 3.5 miles to Salt Creek County Park. Enter the park, pass the entrance booth, and immediately turn right for trailhead parking.

ON THE TRAIL

Port Angeles residents have long known that some of the finest coastal scenery around can be found at nearby Salt Creek County Park. A one-time army post known as Camp Hayden, Clallam County Parks now manages the property complete with campground and trails. A 1500-acre Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) tract encompassing 1166-foot Striped Peak abuts the park to the east. Although heavily logged, the steep northern slopes of the mountain were spared, allowing you to hike amid huge Douglas-firs hundreds of years old.

The well-built trail takes off though a stand of big firs just to the northeast of the parking area. Soon bear right and begin hugging the hillside not far from the coastline, winding through forested flats while listening to waves splash up against ledge and bluff. Continue deeper into the forest, climbing a bench high above the crashing surf. Enter a primeval grove of towering hemlocks, firs, and cedars. If access weren’t so prohibitively difficult, these ancient giants surely would have been logged.

After twisting beneath one big tree after another, the trail climbs to a small dizzying viewpoint of an isolated cove 200 feet below. Be careful while admiring this vista! If you continue, keep skittish dogs and children nearby as the trail rounds the cove high above, coming to a side trail at 1 mile. The trail left drops rapidly to the remote cove. It’s worth the effort, but other beaches in the park can be more easily accessed.

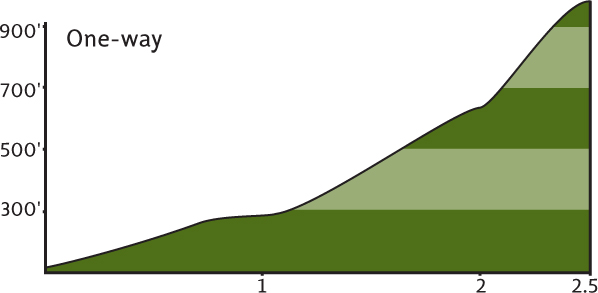

The main trail continues up a damp ravine—a dense fern alley—and uniform second growth replaces the big trees. Cross numerous side creeks that flow down the dark slope. Turning south, the trail climbs steeply, skirting an old cut to emerge on a dirt road at 2.4 miles (elev. 900 ft). Follow the road right a short distance to a viewpoint over a vast expanse of saltwater and Canadian soil. Mount Baker, the San Juans, and Port Angeles can all be seen to the east. Unfortunately, past visitors arriving by motor have not left the summit too appealing, leaving scads of trash behind. (Put the litterers on a chain gang to pick up after themselves!)

It’s possible to return to the trailhead via a series of DNR roads, but it’s a confusing route and often not very scenic, so best to return the way you came.

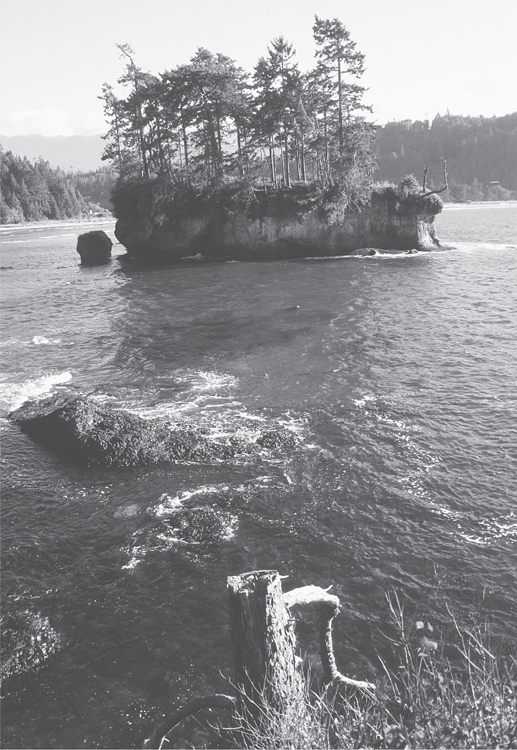

Tongue Point is worth exploring after hiking adjacent Striped Peak.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Back within the park, be sure to sample the short trails leading to the Tongue Point Marine Sanctuary and the flowerpot sea stacks of Crescent Bay. Consider spending the night and letting the surf sing you to sleep.

|

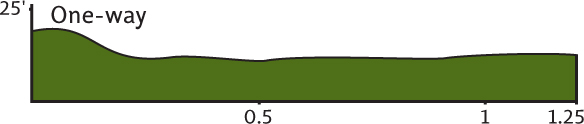

Clallam Bay Spit |

Map: USGS Clallam Bay; Contact: Clallam County Parks, (360) 417-2291; Notes: Dogs must be leashed; GPS: N 48 15.269, W 124 15.635

|

A wild and deserted ocean beach on the Strait of Juan de Fuca? With big waves and lots of marine and bird life, Clallam Bay Spit feels like it should be on the Pacific. But when you look across its rough waters and see a sea of mountains on the horizon, your geographic inclinations are set “strait”! Clallam Bay Spit is a breathtakingly beautiful place to catch a sunset or just to wander aimlessly. Best of all, this “north coast” beach is never crowded. Your fellow hikers are too busy heading to nearby Ozette. |

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles follow US 101 west for 5 miles to the junction with State Route 112. Turn right (west) on SR 112, continuing 44 miles to the community of Clallam Bay. (Alternatively, take US 101 to Sappho and drive SR 113 north to SR 112 and then on to Clallam Bay. This way is longer, but not as curvy.) In Clallam Bay look for a sign indicating “Clallam Bay Community Beach.” Located on your right, the turnoff is near an auto center and across the street from a closed grocery. The trailhead is located at a large parking area. Water and restrooms available.

Beautiful beaches on Clallam Spit—Slip Point in background.

ON THE TRAIL

When Washington State Parks acquired this 33-acre property, the state cooperated with Clallam County Parks to make sure that you, the intrepid hiker, would have easy access to this magnificent parcel. They constructed a wonderful little 0.25-mile trail and a picturesque wooden arch bridge over the Clallam River, enabling access to a 1-mile-long sandy spit.

In the winter of 2003, Mother Nature had a few things to say about beach access, throwing a storm that caused the river to shift and breach the spit. The bridge was also rendered useless, as it was now surrounded by water. And just when the parks department was about to construct a new bridge, the river shifted again. So, before you head this way, contact Clallam County Parks about the status of the spit. There are public access points both east and west of the main entrance, so this wonderful beach is not going to keep you away that easily.

Assuming the bridge is back in place, amble down the short trail, span the fickle Clallam River, and behold one of the finest stretches of beach in the Evergreen State. Wander west for 0.5 mile toward rocky Middle Point (you may have to wade the Clallam River en route—easy in summer, dangerous in winter) . Turn around and kick sand for a mile all the way to the headland at Slip Point, home of a coast guard station and lighthouse. When the tide is low you can comb the pools left behind.

You can spend hours on Clallam Bay Spit just walking back and forth and staring into the surf. But make sure you stay for a sunset on one of your visits. It’s simply radiant.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Over 7 miles of public tidelands can be wandered near the Sekiu River and Shipwreck Point a few miles west of Clallam Bay. Washington State Parks has also acquired property along the Hoko River, about 3 miles west of Sekiu, which has 0.5 mile of nice sandy beach at its mouth.

KLAHOWYA TILLICUM

Many place names on the Olympic Peninsula, like much of the Pacific Northwest, come from the Chinook Jargon. Not an actual language, Chinook is a collection of several hundred words drawn from various Native American tribal languages as well as from English and French. It was used as a trade language among Native peoples, Europeans, and European Americans in the Pacific Northwest throughout the nineteenth century. A unique part of our Northwest cultural heritage, Chinook names are sprinkled throughout the landscape. Below are some Chinook words you will encounter on the Olympic Peninsula.

| chuck | water, river, stream |

| cultus | bad or worthless |

| elip | first, in front of |

| hyas | big, powerful, mighty |

| illahee | the land, country, earth, soil |

| kimtah | following after, behind |

| klahanie | outdoors |

| klahowya | greeting, “how are you?” or welcome |

| klootchman | woman |

| kloshe nanitch | take care, stand guard |

| la push | the mouth (of a river) |

| ollalie | berries |

| potlatch | give, gift |

| sitkum | half of something, part of something |

| skookum | big, strong, mighty |

| tenas | small, weak, children |

| tillicum | friend, people |

| tupso | pasture, grass |

Hurricane Ridge

For many, the Hurricane Ridge region represents the créme de la créme when it comes to day hiking on the Olympic Peninsula. Nowhere else in these rugged mountains can you access alpine meadows and lakes with such ease. Nowhere else on the peninsula are you granted almost nonstop, stunning horizon-spanning views. Many of the area’s hikes start at high elevations and remain high, weaving along lofty ridges as panorama-providing pathways.

But with such notoriety come masses of view-seekers. Many of the trails in this area can get downright crowded, especially on nice weekends (both summer and winter). The Hurricane Ridge Road (Heart o’ the Hills Parkway), which enables such easy access to this high country, is a double-edged sword. On one side, it allows perhaps far too many people for the fragile alpine environment to absorb. But on the other side, it provides access to almost anyone. Indeed, more than a few got their first taste of the Olympics because of this popular parkway, gaining a love and respect for this special place. That’s what happened to me a quarter of a century ago.

|

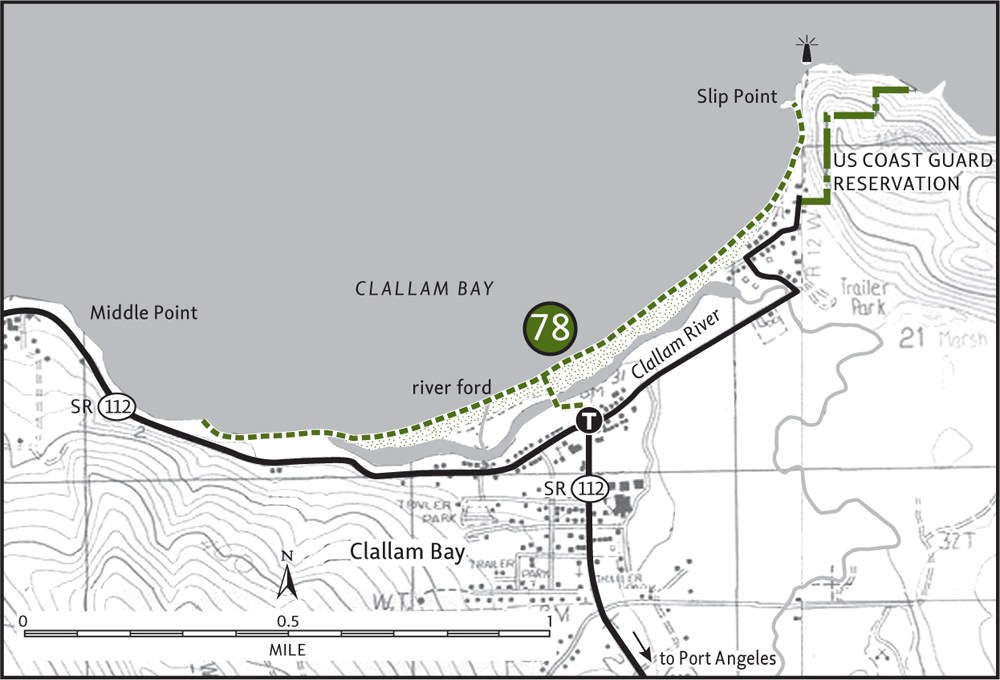

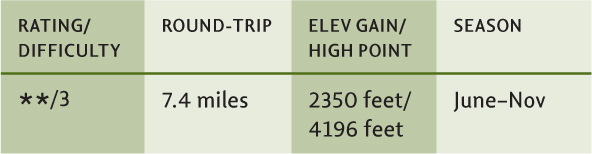

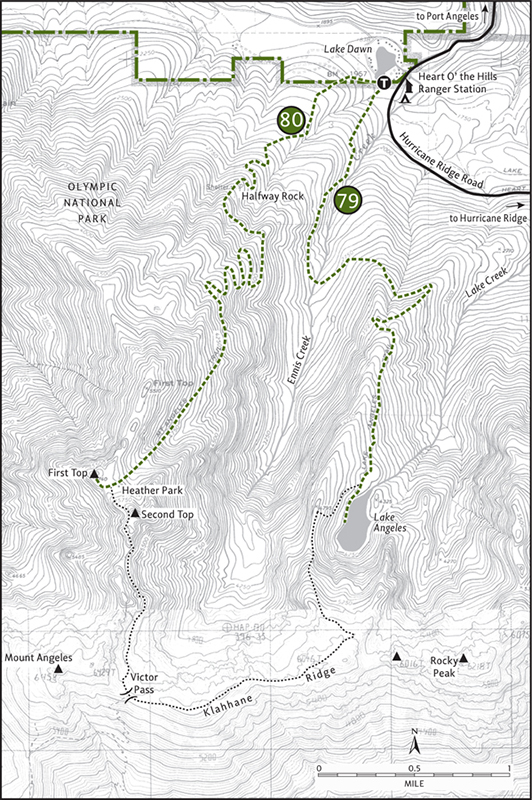

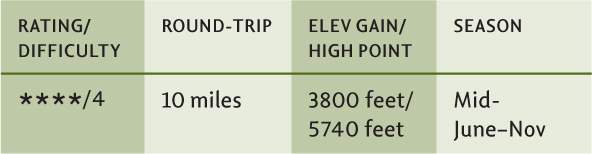

Lake Angeles |

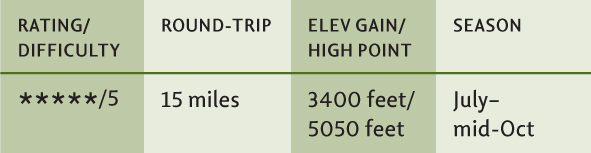

Maps: Green Trails Port Angeles No. 103, Custom Correct Hurricane Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited; GPS: N 48 02.345, W 123 25.916

|

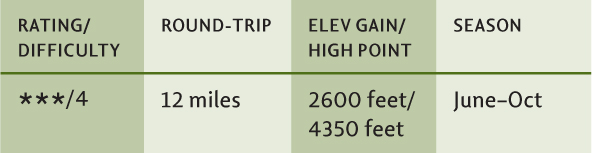

Known for its craggy peaks, wilder-ness coast, and deep lush forests, Olympic National Park contains quite an array of spectacular natural features. But when it comes to alpine lakes, the park seems lacking. Sure, scores of aquatic gems sparkle in the backcountry, but compared to the Cascades, the Olympics come up short. Lake-loving day hikers need not shy away, however, for there are a handful of attainable alpine gems. Lake Angeles is one of them. It’s also one of the largest lakes in the Olympics, and the most popular. |

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles leave US 101 near milepost 249, following Race Street south 1.2 miles to Hurricane Ridge Road (Heart o’ the Hills Parkway) and passing the Olympic National Park Visitors Center and Wilderness Information Center. Proceed on Hurricane Ridge Road for 5 miles. Just before the park entrance booth, turn right (west) to reach a large trailhead parking area.

ON THE TRAIL

From high above on Klahhane Ridge, 20-acre Lake Angeles looks like a teardrop. Occupying a glacial cirque, the lake is ringed on three sides by steep rocky walls. Through most of the summer, tumbling creeks of snowmelt feed the isolated body of water. A small island formed by rockfall and adorned with subalpine firs sits in the middle of the emerald lake.

Beautifully set, Lake Angeles is well-loved by hikers from near and far. The boot-beaten path to its shores attests to this. But this is not an easy hike—the trail gains over 2300 feet in 3.5 miles. Well-shaded, however, you shouldn’t have any trouble overheating while grunting to your objective.

The well-worn path immediately sets out climbing, paralleling Ennis Creek, before making a sharp turn east and heading over to another creek drainage. The trail then makes a sharp turn back west, crosses the creek, and begins to climb straight up a rib, the divide between Ennis and Lake Creeks. Never easing up, the trail works its way into the deep cirque housing the lake.

At 3.7 miles a sign indicates the lake is near. Turn left down a short spur and behold, Lake Angeles. Cool air rushes down the bare slopes above, rippling the lake surface. Sunlight twinkles off of the small waves. It’s a soothing scene, but you won’t be alone here. You’ve earned the right to find a nice spot, however, to enjoy this Olympic aquatic gem.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

If the rugged surroundings intrigue you and you’re full of energy, continue climbing 2000 more feet in 2 more miles to the open slopes of Klahhane Ridge (Hike 81). You can peer right down on the twinkling lake and out beyond to the “big lake,” the ocean waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. A grueling 12.5-mile loop can also be made by following the ridge to the Heather Park Trail (Hike 80) and then back to your vehicle. Snowfields can linger along the ridge into midsummer, so check conditions before striking out.

Lake Angeles as seen from high above on Klahhane Ridge

|

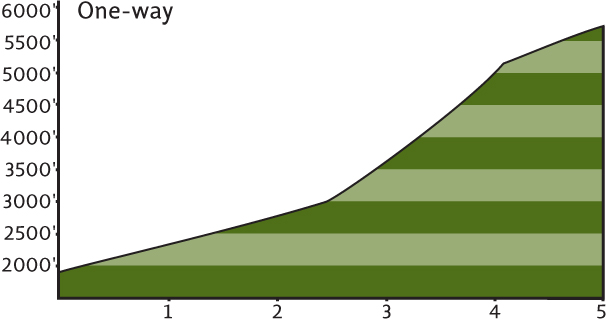

Heather Park |

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge No. 134S, Custom Correct Hurricane Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited; GPS: N 48 02.345, W 123 25.916

Climb a steep ridge high on the shoulder of Mount Angeles to a prominent pinnacle with panoramic views of the Olympic Peninsula. From this point, known as First Top, enjoy first-rate views that encompass snowy Mount Olympus all the way to salty Pillar Point on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. And gracing this heavenly haven on the mountain of angels are delightful rock gardens and fields of blooming heather. Divine, yes, but it’s a devil of a climb!

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles leave US 101 near milepost 249, following Race Street south 1.2 miles to Hurricane Ridge Road (Heart o’ the Hills Parkway) and passing the Olympic National Park Visitors Center and Wilderness Information Center. Proceed on Hurricane Ridge Road for 5 miles. Just before the park entrance booth, turn right (west) and proceed to the large trailhead parking area.

ON THE TRAIL

The trail starts from the west end of the parking lot. If any cars are parked here, chances are the occupants are on the adjacent Lake Angeles Trail. It’s a tough hike to Heather Park, but the trail is in good shape. You will be too after tackling this hike.

Start through a uniform forest of second-growth Doug-fir. The original forest burned in the early twentieth century thanks to homesteaders who didn’t heed Smokey’s sound advice. Through a thick understory, the trail steadily climbs, at times steeply. At 2 miles pass Halfway Rock, a glacial erratic marking the not-quite-midway point to Heather Park. The trail eases somewhat before launching into more switchbacks.

Now skirting along the northeast slope of First Top, a thinning forest reveals glimpses of the amazing views that await you at the summit. Craggy Second Top hovers ahead. The trail soon breaks out into the open, snaking steeply around basalt ledges bursting with blossoming wildflowers.

At 4.2 miles the way levels out, entering a small basin (elev. 5300 ft) tucked between First and Second Tops. This is the beginning of Heather Park, a subalpine bowl of flowers, boulders, heather, and stunted evergreens. Come upon a small creek before making a final climb to wind-blasted and sun-baked Heather Pass. Piper’s bluebell, cinquefoil, and Olympic onion add colorful touches to the drab shale and scree littering the pass.

The view is amazing. But it’s better from First Top, 100 feet higher and reached by following a small way path just to the right. From this basaltic shoulder of Mount Angeles, gaze out in every direction for supreme viewing. Port Angeles and the Strait of Juan de Fuca lie to the north 1 vertical mile below. To the east, follow the strait to islands flanked by snowcapped peaks. To the west, follow the strait as it parts the peninsula from Vancouver Island and leads to the Pacific. And to the south, take in Mount Angeles, Hurricane Hill, the Bailey Range, Mount Appleton, and Snider Ridge—all under Mount Olympus’s watchful eye.

Olympic-endemic Piper’s bellflower grows on the ledges around Heather Park.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Strong hikers can continue 1.5 miles beyond Heather Pass, dropping below Second Top’s cliffs before climbing a high shoulder separating it from Mount Angeles. From there the trail drops into a high open basin and then climbs to Klahhane Ridge (Hike 81). A loop of 12.5 miles can be made by following the Lake Angeles Trail (Hike 79) back to the trailhead. It’s a tough hike over loose scree and past some steep, semi-exposed areas. Snowfields often linger along the ridges beyond Heather Pass well into summer. But if conditions are good and you’re up for the challenge, it’s one of the most scenic hikes in the park.

|

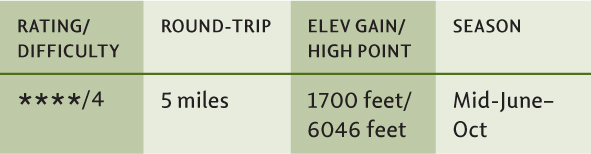

Klahhane Ridge |

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge No. 134S, Custom Correct Hurricane Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 47 59.225, W 123 27.652

Of the four ways to reach the rugged, rocky, and wide-open Klahhane Ridge, the Switchback Trail is the shortest. Ascending 1500 feet in 1.5 miles, this direct approach wastes no time ruthlessly reaching the high ridge crest. You, however, may need to take your time. The south-facing ascent guarantees an early-season entry into the high country, but also exposes you to plenty of direct sunlight. Pack extra water, sunscreen, and your camera for this memorable hike.

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles leave US 101 near milepost 249, following Race Street south 1.2 miles to Hurricane Ridge Road (Heart o’ the Hills Parkway) and passing the Olympic National Park Visitors Center and Wilderness Information Center. Proceed on the Hurricane Ridge Road for 14.8 miles to a small parking lot for the Switchback trailhead on the north side of the road.

ON THE TRAIL

Get an early start, not only to avert overheating, but also to witness a myriad of critters scurrying about. They, too, prefer to avoid the midday heat. Once you reach the barren basalt ledges of Klahhane Ridge, however, chances are good that you’ll be greeted with a refreshing breeze. Far-reaching views from Vancouver Island’s endless summits to the jumbled wall of peaks in the Olympic interior also await you.

Immediately begin climbing. After 700 feet of vertical ascent in just 0.6 mile, come to the junction with the Mount Angeles Trail. To the left this trail leads 3.1 miles to Hurricane Ridge via Sunrise Ridge (Hike 82), a delightful high-country romp through rolling alpine meadows.

Your eyes are set on Klahhane Ridge, so proceed right for some more grueling climbing. At 1.4 miles and 1400 feet of elevation gain, come to Victor Pass and a second junction. The trail left, often snow-covered until midsummer, leads to Heather Park. Take the trail right, the Lake Angeles Trail, to begin a cloud-probing stroll over the exposed ledges and precipitous cliffs of Klahhane Ridge. In a few spots, the trail has been blasted right into the rock, assuring safe passage, though hikers prone to vertigo may want to opt for Sunrise Ridge (Hike 82).

Venture east along Klahhane, dipping a little and climbing a little for 1.25 miles to a 6046-foot knoll, a logical turnaround point for day hikers. Beyond, the trail drops mercilessly 2000 feet to tear-shaped Lake Angeles (Hike 79). If you continue a little ways from the knoll, you’ll be able to see it, one of the largest lakes in the Olympics, way, way down below.

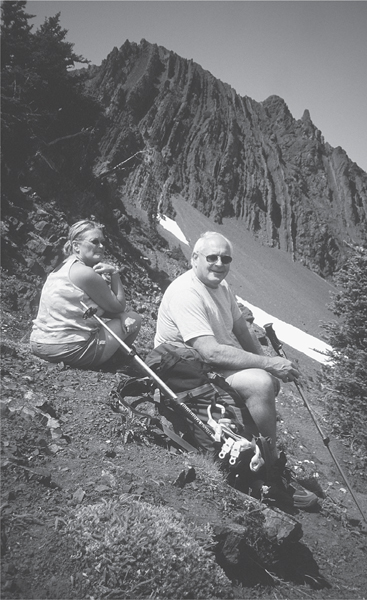

Rick and Marti take a break at Victor Pass along Klahhane Ridge.

Common sense tells you to save Lake Angeles for another day and enjoy the views instead. To the south, Elk Mountain and the Grand Ridge dominate the skyline. Craggy, glacier-covered Mount Cameron peeks out behind. The deep green Cox Valley lies directly below in the foreground. To the north are the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Vancouver Island, and British Columbia’s Coast Ranges. Mount Baker rises abruptly in the east. Directly below are Port Angeles and Ediz Hook jutting into the strait.

Klahhane is a Chinook word meaning “outdoors.” Upon completing this hike, you’ll probably add “great” when describing this prominent ridge.

|

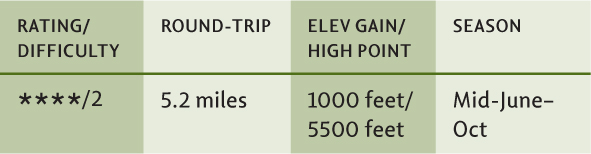

Sunrise Ridge |

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge, No 134S, Custom Correct Hurricane Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 47 58.203, W 123 29.702

|

Sunrise Ridge delivers the same jaw-slacking views as Hurricane Hill, but without the asphalt and crowds. Chances are also good that on Sunrise Ridge you’ll encounter some resident wildlife, especially in the morning. Deer, bear, coyote, and the ubiquitous chipmunk all make themselves at home along this delightful trail. And wildflowers—they grow in profusion, from magenta paintbrush, to spreading phlox, penstemon, lupine, bistort, and larkspur. When your nose isn’t glued to the ground admiring a myriad of blossoms, your eyes will be strained from scanning the horizons. |

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles leave US 101 near milepost 249, following Race Street south 1.2 miles to Hurricane Ridge Road (Heart o’ the Hills Parkway) and passing the Olympic National Park Visitors Center and Wilderness Information Center. Proceed on the Hurricane Ridge Road for 17.5 miles to the Hurricane Ridge Visitors Center. The trail begins on the north side of the large parking area.

ON THE TRAIL

From the parking lot, head north on the Mount Angeles Trail, the first 0.3 mile following the paved High Ridge Nature Trail. Real tread begins after cresting a small knoll. Just beyond, in a small saddle, come to a junction. The trail left leads 0.1 mile to Sunrise Point, a 5500-foot viewpoint on the ridge. It’s a nice spot, but it gets better down the trail. Carry on, dropping 250 feet from the saddle, leaving the hubbub of Hurricane Ridge behind.

Undulating between groves of subalpine fir and resplendent alpine meadows, the trail works its way over and around a handful of knolls. Gaze north, out across the Strait of Juan de Fuca to massive Vancouver Island and its scads of mountains. Scan the strait eastward to snowy Mount Baker rising above a myriad of islands and inlets. Turn your attention south to the Olympic interior, to an emerald sea punctuated by craggy summits adorned in ice and snow. Mount Olympus, the centerpiece of this magnificent wilderness setting, dominates the southwestern horizon.

Of course, it’s impossible to ignore the imposing peak in front of you—the one growing taller with each step—6454-foot Mount Angeles. At 2.6 miles the trail delivers you right to the base of this locally prominent peak. A climbers path takes off to the left, while the Mount Angeles Trail continues right, skirting the southern slopes of the rocky mountain. Feel free to venture a ways up the steep climbers path through more meadows and subalpine forest. Stop when the trail reaches scree, unless you’re trained and prepared to make a class 3 scramble. In any case, the views along Sunrise Ridge are as good as any from Mount Angeles.

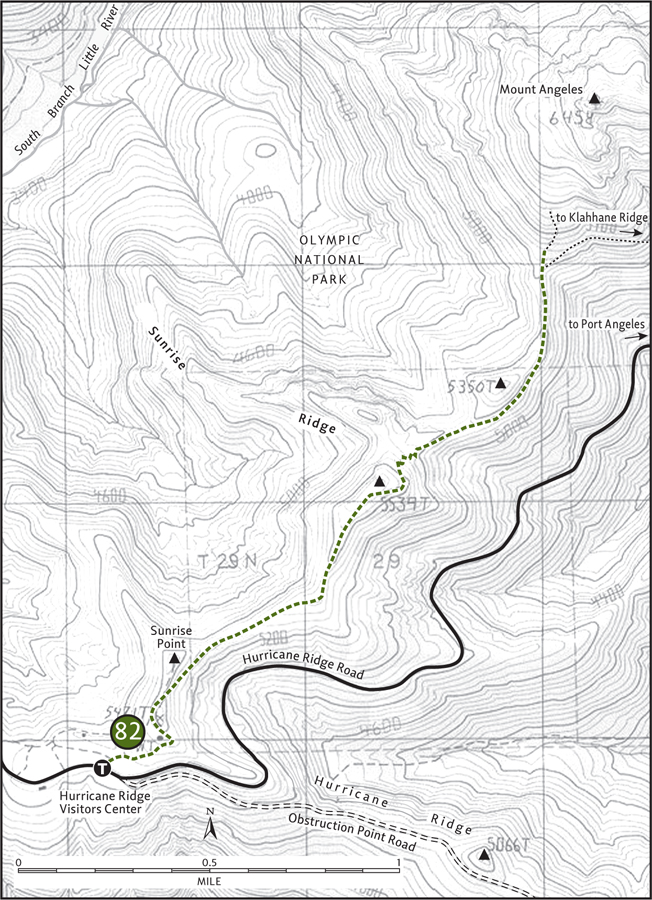

The Sunrise Ridge Trail marches off towards Mount Angeles.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

A half mile beyond the climbers path junction, the trail intersects the Switchback Trail (Hike 81). If you can arrange for it, make your hike one-way by hiking down it. Of course, you can always continue on the Mount Angeles Trail, climbing 800 feet to the rugged aerie of Klahhane Ridge.

|

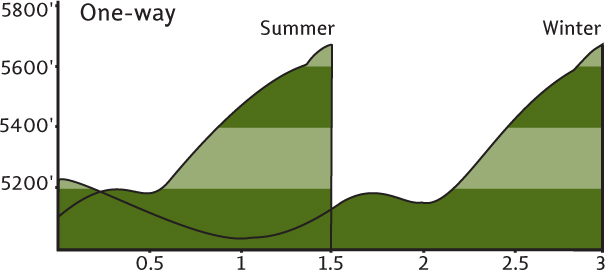

Hurricane Hill |

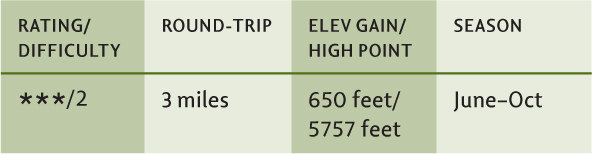

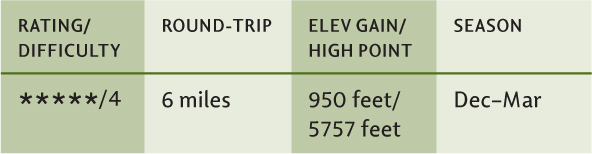

Summer

Winter

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge No. 134S, Custom Correct Hurricane Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym. Winter Hurricane Ridge Road conditions, (360) 565-3131; Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required. Dec–Mar the road is open Fri–Sun weather permitting; GPS: N 47 58.594, W 123 31.069

|

A paved path to an emerald knoll with horizon-spanning views from snowy Olympus and Mount Baker to the azure waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Choked in the sunny summer months with sauntering tourists, Hurricane Hill has helped introduce young and old, local and foreign, to the wonders and delights of the Olympic high country. This hike is perfect for kids in the summer, and even hard-core hikers need not shun it. And when winter spreads its white coat upon the open slopes, it’s a whole different adventure. |

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles leave US 101 near milepost 249, following Race Street south 1.2 miles to Hurricane Ridge Road (Heart o’ the Hills Parkway) and passing the Olympic National Park Visitors Center and Wilderness Information Center. In the summer, drive 17.5 miles to the Hurricane Ridge Visitors Center and continue 1.5 miles farther on the narrow Hurricane Hill Road to trailhead parking. In the winter, stop at the visitors center. Water and restrooms available at the visitors center.

ON THE TRAIL

Summer: For summertime visits, the way is quite simple and straightforward. Follow the procession of people in front of you on the paved path 1.5 miles to the 5757-foot pinnacle, where views abound. Take in the mountains, from Mount Baker in the Cascades, to Mount Garibaldi in British Columbia’s Coast Ranges to the interior Olympic peaks. Enjoy views of the green cirque below that forms the ridge between Hurricane Hill and Sunrise Point. Wildlife, including bears, are often seen feeding below. People-friendly deer will probably be loitering on the summit. Don’t feed them—they need to fend for themselves if they are to survive the winter.

Winter: For winter visitors, Hurricane Hill offers one of the most-accessible snowshoe routes in the Olympics. Although not overly difficult, windy and icy conditions can make the route treacherous. Hurricane Hill is subject to blinding snowstorms and howling, frostbite-inducing winds. Snow along the ridge forms cornices and the steep slopes are subject to avalanches. But when conditions are optimal—stable snow and stable weather—the trek to Hurricane Hill is incredibly rewarding. Always check with the park about conditions before setting out. The park also offers guided snowshoe hikes along the ridge on winter weekends, perfect for introducing novices to snowshoeing.

No crowds in winter on Hurricane Hill—looking west towards Mount Appleton

Along the way enjoy a winter wonderland landscape, with Mount Olympus and the Bailey Range forming a great white wall to the southwest. Venture out on the broad western shoulder of Hurricane Hill for breathtaking views down into the Elwha Valley. In winter, Hurricane Hill is a whole different world.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Summertime hikers can head down off of Hurricane Hill on three different one-way adventures to the valleys below. For the best of the three, veer off the trail just below the summit on the trail leading down to the Elwha Valley. Long before the Hurricane Ridge Road was built, this was one of the ways to access Hurricane Hill. Roam for 1.5 miles on this path through glorious alpine meadows teeming with deer, grouse, and views to a 5000-foot knoll. Beyond, the trail plummets 4500 feet in 4.6 miles to the valley—a good one-way trip with a car shuttle, or a round trip for masochists. The 8-mile Wolf Creek Trail is the easiest additional hiking option, while the 8.5-mile Little River Trail is the most difficult and loneliest.

|

PJ Lake |

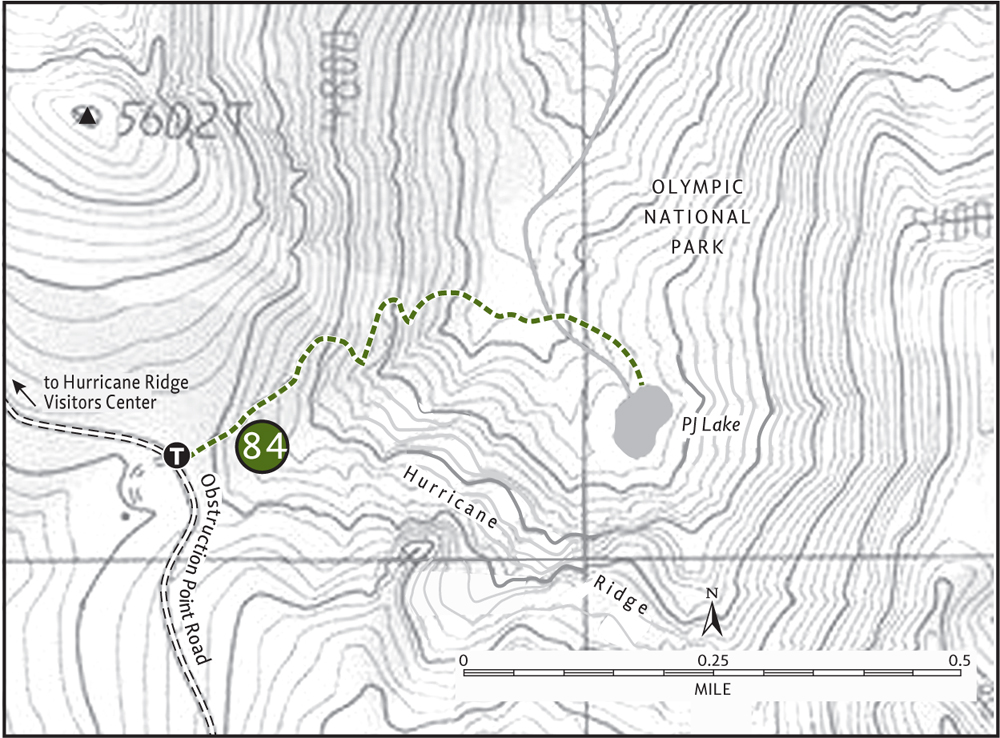

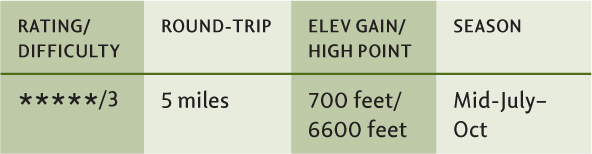

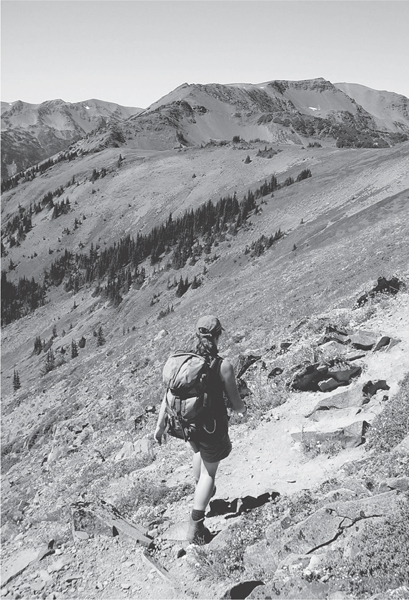

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge No. 134S, Custom Correct Hurricane Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required. Heavy winter snowfall can delay opening of Obstruction Point Road; GPS: N 47 56.750, W 123 25.528

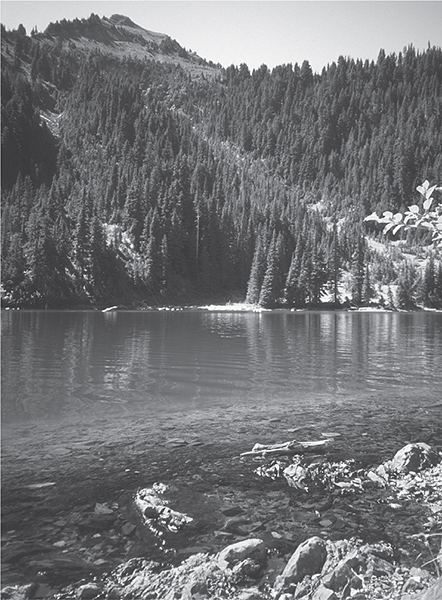

A tiny lake tucked in a hidden bowl on Hurricane Ridge, PJ Lake entertains few hikers due to its rough-and-tumble approach. On a trail pockmarked with deer tracks, drop steeply for 600 feet before climbing 350 feet to reach this emerald pool—all in less than a mile! Is it worth it? If you cherish solitude and the opportunity to spot wildlife up close, yes. Wildflowers and a pretty cascade offer a little incentive too.

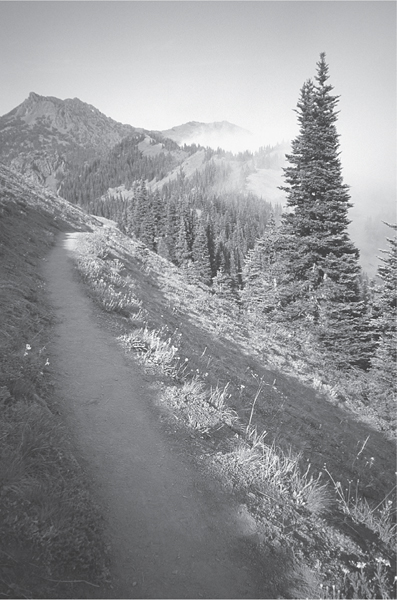

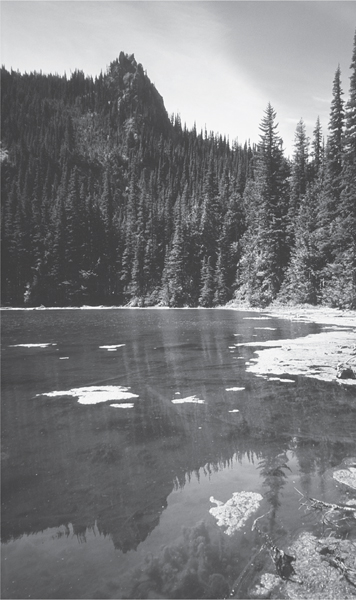

Secluded PJ Lake

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles leave US 101 near milepost 249, following Race Street south 1.2 miles to Hurricane Ridge Road (Heart o’ the Hills Parkway) and passing the Olympic National Park Visitors Center and Wilderness Information Center. Proceed on the Hurricane Ridge Road for almost 17.5 miles. Just before the large parking lot at Hurricane Ridge, make a sharp left turn on Obstruction Point Road. Follow this very narrow (and harrowing to some) gravel road for 3.8 miles to the Waterhole, a former picnic area. The trail begins on the left side of the road.

ON THE TRAIL

Start in a stand of subalpine fir before rapidly dropping through open forest, huckleberry patches, and meadow clumps. Watch your footing—critter burrows blemish the tread. When not looking down, gaze out to a window view of the Dungeness Spit. The steep hillside often teems with browsing deer. Remind them to stop cutting the switchbacks.

After dropping 600 feet in 0.6 mile, angle east in a cool glen, crossing two streams. The second one cascades 30 feet over a mossy ledge. Now climb 350 feet, reaching pretty little PJ Lake at 0.9 mile from the trailhead, and find yourself in a semi-open bowl flanked with Alaska yellow cedars, big silver firs, and brushy avalanche chutes. The lakeshore is graced with purple asters and columbine, and jumping trout and frogs break the silence of the basin. A grassy bench near the lake’s outlet invites picnicking.

If you’ve hiked in during late summer, allow time for harvesting huckleberries on your way out. It’ll make the return more manageable, not to mention delicious.

|

Grand Ridge |

Maps: Green Trails Mt Angeles No. 135, Custom Correct Hurricane Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 47 55.105, W 123 22.927

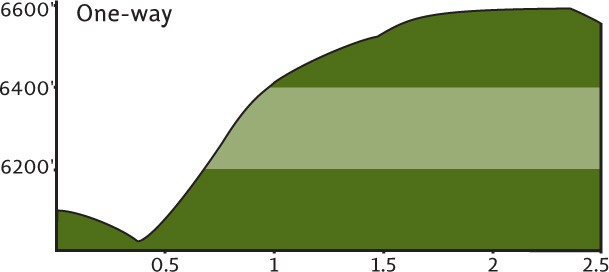

Grand Ridge is appropriately named. The views are grand, the wildflowers are grand, and trekking across its wide open slopes is a grand experience. But it gets grander. Reaching an altitude of 6600 feet, this trail is among the highest in the Olympics and one of the most scenic, with nonstop views of jagged glacier-covered peaks, deep valleys of unbroken old growth, and miles upon miles of wildflower-saturated meadows and tundra.

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles leave US 101 near milepost 249, following Race Street south 1.2 miles to Hurricane Ridge Road (Heart o’ the Hills Parkway) and passing the Olympic National Park Visitors Center and Wilderness Information Center. Proceed on the Hurricane Ridge Road for almost 17.5 miles. Just before the large parking lot at Hurricane Ridge, make a sharp left turn on the gravel Obstruction Point Road. Follow this narrow (and harrowing to some) gravel road 7.7 miles to its end at the trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

The complete trek across Grand Ridge from Obstruction Point to Deer Park is 7.5 miles, with a whole lot of up and down. It ranks as one of the all-time great ridge traverses in the Olympics. But unless you can arrange for a pick-up at the other end, it’s a tough 15-mile round trip that only a few hardy souls are willing to make. The 5-mile out and back traversing the slopes of Elk Mountain, the highest point on the ridge, should do the trick for most. You’ll be able to take in Grand Ridge’s finest views, with plenty of time to stop and smell the copious flowers along the way.

A hiker heads across Grand Ridge.

In wide-open country, start off by descending slightly toward the Badger Valley. In 0.2 mile the Badger Valley Trail takes off right (see Hike 86), dropping steeply below into emerald oblivion. Your trail angles left, rounding Obstruction Peak before traversing the barren, wind-battered, and sun-dried south face of Elk Mountain. Some years, snows linger in the shadows of Obstruction Peak, making travel dangerous. If the steep gullies haven’t melted out, consider hiking to Grand Valley instead (Hike 86).

Once the snow is gone, however, it’s high and dry on the ridge. Pack plenty of water. After 1 mile of huffing and puffing the grade eases, allowing you to concentrate on the fascinating alpine tundra cloaking Elk Mountain. Put your nose to the ground to admire floral arrangements of lupine, columbine, tiger lily, paintbrush, cow parsley, rosehip, penstemon, larkspur, gentian, cinquefoil, and a handful of other showy blossoms. Watch the meadows for movement too. You may spot one of the horned larks that calls Grand Ridge home.

At 2 miles and an elevation of 6600 feet—the highest maintained tread in the park—come to a junction with the Badger Valley cutoff, an option for an interesting, albeit difficult return. Continue on relatively flat terrain for another 0.5 mile, basking in mountain breezes and soaking up views. From the sparkling waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca to the snowy summits of Mounts Olympus, Cameron, Carrie, and Deception, grand views emanate.

At 2.5 miles the trail makes a steep plunge down a rocky slope on its way to Maiden Peak. This is a good place to start retracing your steps, savoring this alpine beauty a little bit longer.

|

Grand Valley |

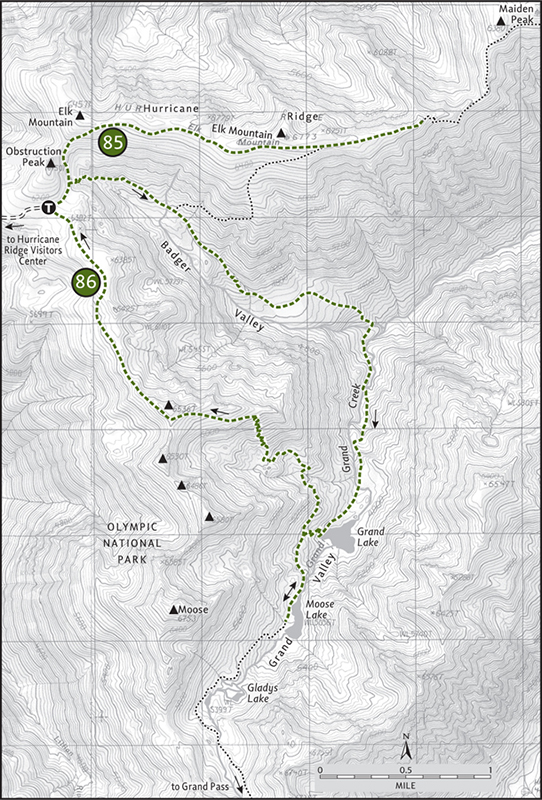

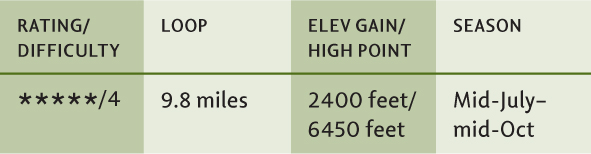

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge No. 134S, Custom Correct Hurricane Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 47 56.750, W 123 25.528

In a park where more than a few valleys can vie for the name “grand”, this one is the grand contender. A necklace of sparkling alpine lakes adorning bold mountain faces spans this mile-high valley. Wildflowers, old growth, alpine tundra, deer, marmots, bear—they’re all here in this outdoor cathedral. Your ticket into this wild kingdom comes at minimal cost—the trail is mostly downhill on a good grade, though you do pay the piper on the way out on a grueling ascent. But it’s all worth it.

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles leave US 101 near milepost 249, following Race Street south 1.2 miles to Hurricane Ridge Road (Heart o’ the Hills Parkway) and passing the Olympic National Park Visitors Center and Wilderness Information Center. Proceed on the Hurricane Ridge Road for almost 17.5 miles. Just before the large parking lot at Hurricane Ridge, make a sharp turn on Obstruction Point Road. Follow this narrow (and harrowing to some) gravel road 7.7 miles to its end at the trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

The quickest way into Grand Valley is via the Grand Pass Trail, climbing along Obstruction Ridge and then brutally descending to Grand Lake. Consider this loop as an alternative. Sure, it’s longer and, sure, there’s more overall climbing involved, but the gentle descent will save your knees and you’ll get to traverse the quiet Badger Valley en route. Bursting with flowered meadows and fluttering with animal activity, this valley is neglected by those in a hurry to get to Grand Valley. Don’t expect any badgers, though—it was named after a ranger’s horse. There are lots of Olympic marmots, however—close enough.

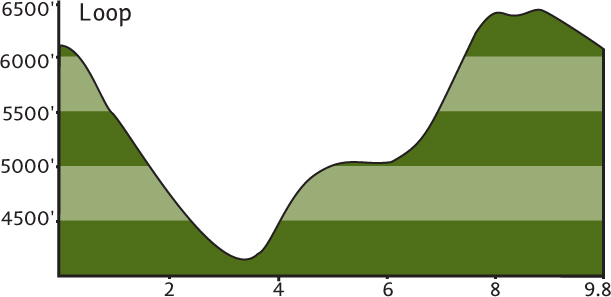

Moose Lake in the Grand Valley

ONLY IN THE OLYMPICS

Because the Olympic Peninsula is in essence a biological island—isolated by eons of glacial ice followed by the “moats” of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Puget Sound—many of its life forms are found nowhere else on the planet. The peninsula is home to eight plant endemics and fifteen animal endemics.

Among the region’s unique fauna are the Olympic marmot, Olympic yellow-pine chipmunk, Olympic snow mole, Olympic Mazama pocket gopher, Olympic ermine, Olympic torrent salamander, Olympic mudminnow, Olympic grasshopper, arionid jumping slug, and the Quileute gazelle beetle.

Among the peninsula’s unique flora are the Olympic mountain milk vetch (a plant endangered because of introduced mountain goats), Piper’s bellflower, Olympic mountain groundsel, and Flett’s violet.

Among original (but not endemic) inhabitants that are missing today from this biologically diverse landscape is the gray wolf. Extirpated by early settlers and the Park Service itself (talk about a misguided predator policy), the majestic howl of Canis lupis hasn’t been heard in the Olympic backcountry since the 1920s. Conservationists hope that this noble creature and important component of the Olympic ecosystem can someday be reintroduced.

Start by heading toward Grand Ridge (Hike 85), making a right turn after 0.2 mile onto the Badger Valley Trail. Descend in the wide U-shaped valley, hopping over rivulets and brushing against clumps of fragrant greenery. Try not to fall into a marmot burrow.

After passing the Elk Mountain cutoff at 1.1 miles, enter subalpine forest. Undulating between meadow and forest, cross Badger Creek at 2.8 miles (elev. approx. 4000 ft). Then, with Grand Creek at your side, begin the gradual climb to Grand Lake. The forest thins as you ascend and cross brushy avalanche chutes and march over glacial moraine. After gaining 800 feet in just under 2 miles, come to a marshy area that announces that Grand Lake is nearby.

It’s a pretty big lake in a pretty big bowl. Cascading waters from above echo over the placid lake waters. Grand Lake is appealing, but the next lake is much grander. Proceed on stones steps and tight switchbacks through a flower-studded meadow of swaying golden grasses to a junction. Your return is via the trail right. Head left. After an easy 0.5 mile, emerge on an open ledge above the sparkling waters of Moose Lake (elev. 5075 ft)—like Badger Valley, a misnomer. There are no moose here; the lake was named for Frank Moose, whoever he was.

With easily one of the most spectacular backdrops of any Olympic alpine lake, Moose is surrounded by black-shale pinnacles garlanded with verdant forest. Roam the lakeshore—the open ledge yields to grassy shoreline. Share the crystal waters with fly-snapping trout.

When you must relinquish this grand kingdom to the deer and marmots, prepare yourself for the excruciating exodus. The trail back climbs 1400 steep feet in 2.4 miles. Look back over your shoulder while catching your breath. Grand Valley’s aquatic jewels twinkle in the late afternoon sunlight.

Once you crest Obstruction Ridge, enjoy nearly 2 miles of alpine tundra with sweeping views over the Lillian River valley all the way to Olympus. Grunt up one last speed bump, and then enjoy a downhill glide to close the loop.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

One mile beyond Moose Lake is little Gladys Lake, set in a high grassy and moraine-filled bowl. Continue another 1.4 miles to 6400-foot Grand Pass and take a 0.3-mile trail to 6701-foot Grandview Mountain for an awesome view of glacier-covered Mount Cameron, wild and lonely Cameron Creek Valley, and gorgeous Lillian Lake.

Elwha River Valley

Comprising nearly 20 percent of Olympic National Park’s landmass, the Elwha River is the largest watershed in the park. Cutting a deep green valley in a sea of rugged peaks capped with ice and snow and adorned in alpine meadows, the Elwha consists of some of the finest hiking country anywhere.

While backpackers retrace the historic Press Expedition’s 1889–90 traverse across the Olympics, or access routes to remote Hayden Pass or the astonishing Bailey Range traverse, there is plenty of spectacular country attainable to day hikers in the Elwha too. All along the river’s northern reaches, wildlife-rich meadows, forests that have stood for centuries, and miles of stunning landscapes can be explored in a day or less.

Strong day hikers can push themselves farther—into the surrounding high country to remote alpine lakes and meadows. They can gaze out from above to a landscape nearly void of human interferences, witnessing just how grand and wild the Elwha country remains.

|

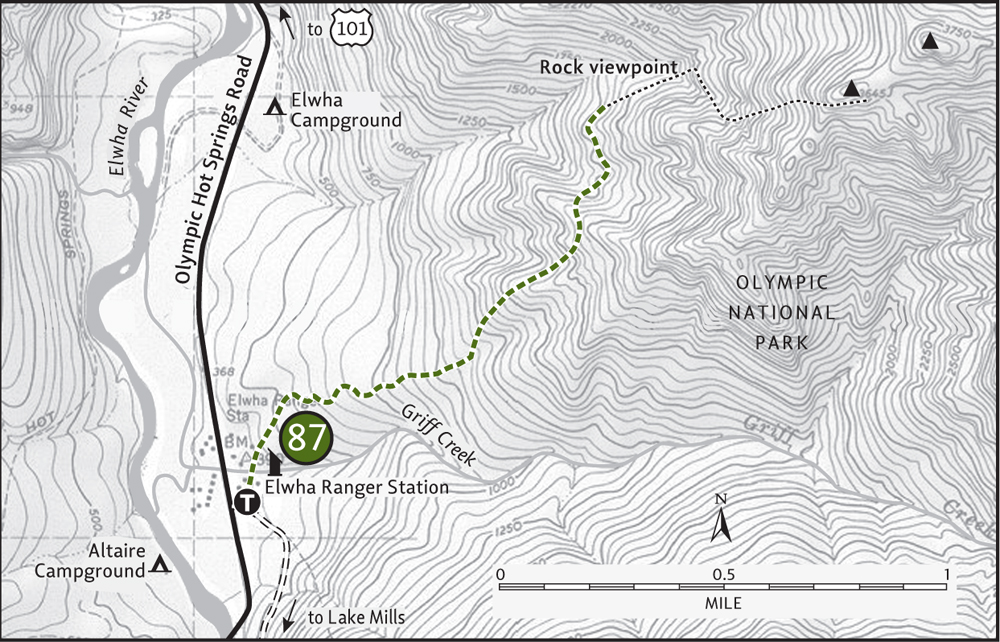

Griff Creek |

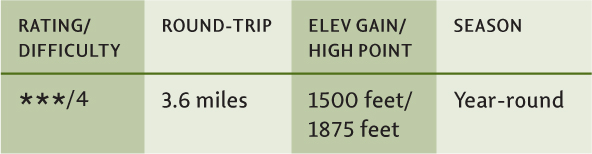

Maps: Green Trails Joyce No. 102, Custom Correct Elwha Valley; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 48 00.994, W 123 35.407

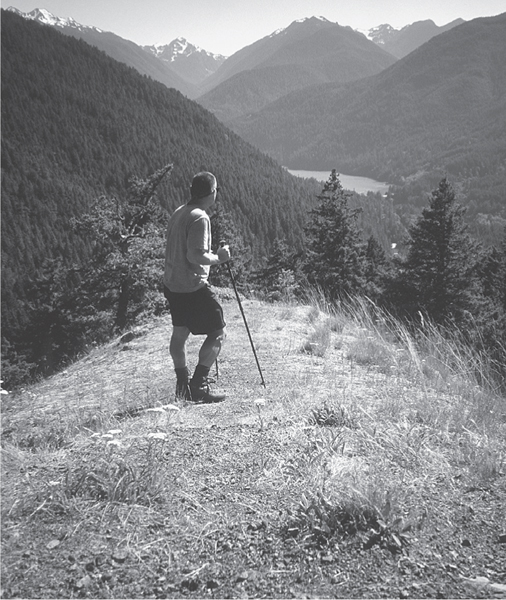

Ascend a steep and arduous hillside to a sun-kissed ledge that grants panoramic perspectives of the wide and wild Elwha River valley, from snow- and ice-covered Mount Carrie down to the twinkling turquoise waters of Lake Mills. One of the Olympic National Park’s least hiked trails, Griff Creek guarantees plenty of solitude—even when the Elwha Valley is hopping with activity.

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles follow US 101 west for 9 miles. At milepost 240, before the Elwha River Bridge, turn left onto Olympic Hot Springs Road (signed “Elwha Valley”). Follow this good paved road, and in 2 miles enter Olympic National Park. In 2 more miles reach the Elwha Ranger Station. Park here. The trail begins behind the building. Water and restrooms available.

ON THE TRAIL

Don’t let the distance fool you. This is not an easy hike. The trail climbs 1500 feet in a little over 1.5 miles. But here’s the payoff: though you’re likely to run into deer, hare, and other critters, chances of encountering a fellow human are slim to none. Despite being named after Griff Creek, the trail travels along a dry ridge nowhere near the waterway. Pack lots of water.

Begin in a daisy-dotted meadow just to the rear of the Elwha Ranger Station. Traverse a park compound, entering a cool and mature forest of fir and cedar. Griff Creek can be heard roaring in the distance, but that sound soon becomes a memory. Despite being lightly traveled, the tread is good and the trail is regularly maintained.

At 0.5 mile cross a seasonal creek bed. The way now wastes no time rising from the moist valley floor to a dry south-facing slope. As you ascend via a series of tight, steep switchbacks the forest canopy thins, revealing teaser views of what lies ahead. At 1.6 miles emerge on a dry ledge. Manzanita and madrona frame a view east to the prominent Elwha River range pinnacle, Unicorn Peak.

Next, hike one sweeping switchback that delivers you to the top of that ledge. A sign indicates “Rock viewpoint el. 1875 feet.” Drop your pack, grab your water bottle, and stake a claim to this picture-perfect promontory. Lake Mills and the Elwha River lie directly below. Mount Carrie towers above. Directly across the wide valley admire the imposing and inhospitable wall of Baldy and the Happy Lake Ridge guarding the Hughes Creek drainage.

The author enjoys the view of Lake Mills from the Griff Creek Trail.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Most day hikers will be content, calling it quits at this first viewpoint. But another fine lookout is reached at 2.3 miles (elev. 2400 ft). Beyond that, the trail climbs an insane 800 feet in 0.5 mile on rough and rocky tread to a ledgy terminus with an impressive view of Hurricane Hill, Griff Peak, and the Unicorn. There are also some other nice, lightly traveled trails in the Elwha Valley to consider. Cascade Rock is reached in 2 miles after climbing 1500 feet. The West Elwha Trail takes off from the Altaire Campground on a 3-mile up-and-down course along the river. There’s good car camping at both Altaire and Elwha Campgrounds.

|

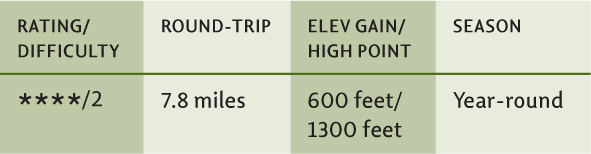

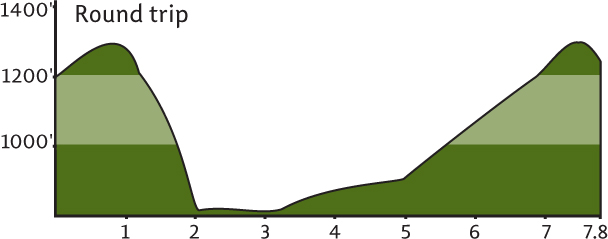

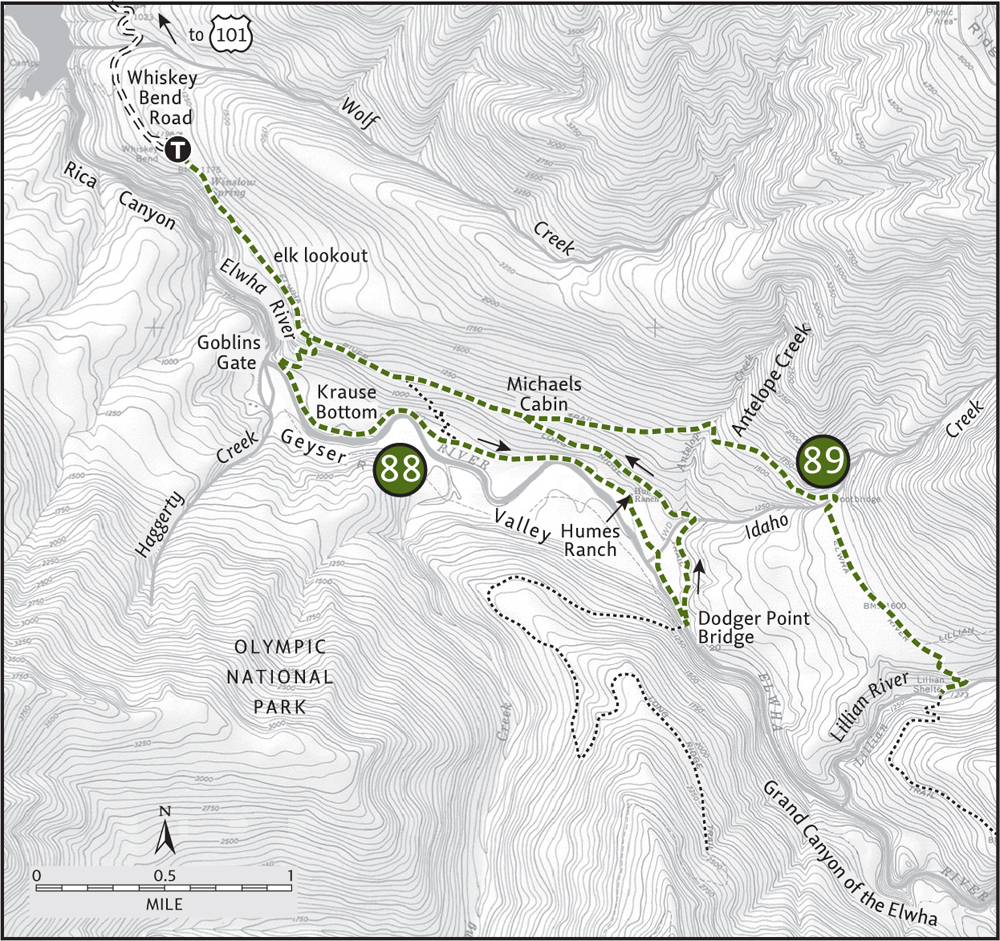

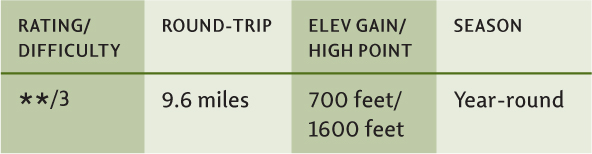

Geyser Valley |

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge No. 134S, Custom Correct Elwha Valley; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required. Trail near Krause Bottom received considerable storm damage in December 2007; check with ranger on current status; GPS: N 47 58.055, W 123 34.941

|

Geyser Valley is a misnomer: there aren’t any geysers in this valley. The Press Expedition of 1889–90—that group of intrepid souls intent on exploring the Olympic interior—either mistook thumping grouse or swirling low clouds when they bestowed their geothermic moniker on this valley. But geyser or no, you won’t be steaming after hiking this beautiful region of the Elwha Valley. Stroll alongside the Elwha River’s churning waters and lounge on its grassy and rocky banks. Snoop around pioneer homesteads, and scope for elk and bear feeding in surrounding pastures. Wildlife and history spout from the Geyser Valley. |

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles follow US 101 west for 9 miles. At milepost 240, before the Elwha River Bridge, turn left onto Olympic Hot Springs Road (signed “Elwha Valley”). Follow this good paved road, and in 2 miles enter Olympic National Park. In a hair over 2 more miles, just past the Elwha Ranger Station, turn left onto Whiskey Bend Road. Follow this narrow gravel road 4.5 miles to its end at the trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

Start by heading down the Elwha River, a super-highway trail. This well-trodden path has been delivering visitors into the Olympic wilds ever since James Christie and company blazed a route across these parts well over a century ago. Begin by gently climbing thorough mature forest and then younger timber (thanks to a series of early twentieth-century fires).

At 0.8 mile a small spur leads right to the Elk Overlook. Here scan the mighty river flowing 500 feet below. The large grassy bend was once part of the Anderson Ranch homestead and is now a favorite grazing ground for resident elk. Continue through open forest, coming to a junction at 1.2 miles with the Rica Canyon Trail. Head right on it, dropping 500 feet in 0.5 mile through a 1970s fire-damaged forest to the river bottom. Take the short spur to Goblins Gate, a rocky narrow chasm funneling the Elwha’s swiftly moving waters.

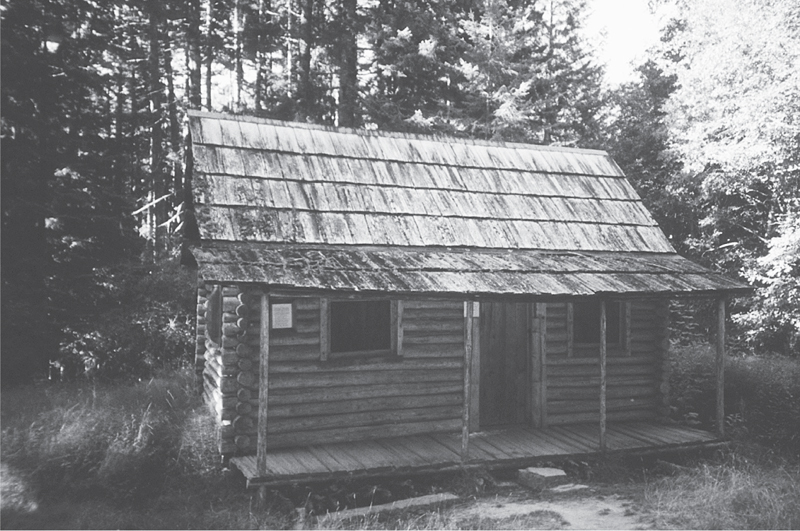

Now work your way upstream on the Geyser Valley Trail. Traverse meadows and fir groves. Rub shoulders with the churning river at wide bends and rocky ledges. At 2.7 miles come to the Krause Bottom Trail. The trail left climbs 0.5 mile back to the Elwha River Trail. Head right for more delightful riverside walking. At 3.4 miles arrive at Humes Ranch on a grassy bluff. Inhabited until 1934, a small cabin remains, restored by the Park Service.

A trail leads left back to the Elwha, but you have more valley to see. Continue right, dropping off of the bluff. Pass a campsite by a sprawling meadow, and then climb onto a high river bank that grants sweeping views of the river. Work your way across Antelope Creek, which may be tricky during rainy periods, and come to a junction with the Long Ridge Trail at 4 miles.

Before turning left to head back to your vehicle, consider a 0.7-mile side trip on the Long Ridge Trail. Follow rebuilt tread climbing around a big slide before dropping to the Dodger Point Bridge at the mouth of the Grand Canyon of the Elwha. This deep, dark gorge is an impressive sight to behold.

To close the loop climb gently 1.3 miles along the Long Ridge Trail back to the Elwha River Trail at Michaels Cabin, a 1906 homestead. Continue left on the Elwha River Trail, ignoring all side trails to return to your vehicle in 2.3 miles.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Just past the Dodger Point Bridge, an old but discernible trail drops to the river’s shoreline. Hikers with good routefinding skills might be able to follow this trail for 2 miles to the old Anderson Ranch site.

This trail hugs the mighty Elwha in the Geyser Valley.

|

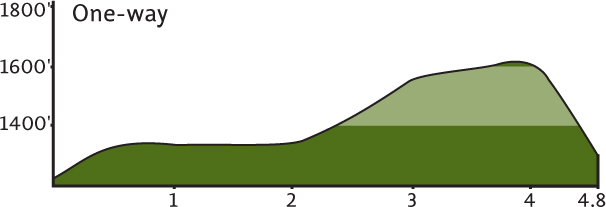

Elwha Valley and Lillian River |

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge No. 134S, Custom Correct Elwha Valley; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 47 58.055, W 123 34.941

|

A hike along the mighty Elwha River is a trip into the very heart of the Olympic Peninsula. From its remote point of origin on the rugged southern slopes of Mount Barnes, practically at the exact center of the national park, the Elwha flows 45 miles to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, draining over 300 square miles of surrounding wilderness and passing through one of the largest tracts of old growth left in America. But you don’t need to travel far to experience this historic and wildlife-rich river valley. The hike to Lillian River, one of the Elwha’s major tributaries, will suffice. |

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles follow US 101 west for 9 miles. At milepost 240, before the Elwha River Bridge, turn left onto Olympic Hot Springs Road (signed “Elwha Valley”). Follow this good paved road, and in 2 miles enter Olympic National Park. In a hair over 2 more miles, just past the Elwha Ranger Station, turn left onto Whiskey Bend Road. Follow this narrow gravel road 4.5 miles to its end at the trailhead. Privy available.

Michaels Cabin on the Elwha River Trail

ON THE TRAIL

If you’re itching for a small taste of the Olympic interior, or looking for a good long winter hike, the Elwha River Trail should satisfy your restlessness. Following the route of the famed 1889–90 Press Expedition, this well-maintained trail will deliver you with ease to the same points that the Press Party struggled to get to.

From the trailhead, the trail bypasses the narrow gorge known as the Grand Canyon of the Elwha, traversing slopes high above it. At 1.2 miles you’ll come to a junction with the Rica Canyon Trail, which drops steeply to Geyser Valley (Hike 88). After another 0.5 mile reach the Krause Bottom Trail, which also drops to Geyser Valley. Continue on the main trail, and after another 0.6 mile arrive at Michaels Cabin, a 1906 homestead once occupied by predator hunter “Cougar Mike.” The resident wildcats have rebounded nicely since Michael’s departure.

The Long Ridge Trail veers right at the cabin, but continue left on the Elwha River Trail. Climb a little, leaving the sound of the Elwha well in the distance. Between Antelope and Idaho Creeks, look for a handful of old trees bearing original ax blazes from the Press Expedition. Through stands of second-growth forest teeming with an understory of salal (fires swept the region in the early 1900s), the trail reaches an elevation of 1600 feet.

At 4.3 miles reach a junction with the Lillian River Trail. Stay on the Elwha River Trail and come to Lillian River in another 0.5 mile and after the trail steeply drops 300 feet. Here, amid good campsites, find yourself a nice picnic site by the pristine tributary. Contemplate how long it took the Press Expedition to get to this spot (two months), and then, avoiding smugness, pat yourself on the back for your rapid passage.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Head up the lonely Lillian River Trail for 2.8 miles. Chance of encountering fellow hikers: low. Bears, elk, and deer: high.

|

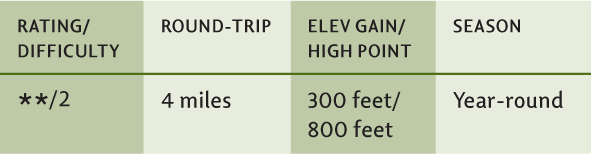

Lake Mills |

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge No. 134S, Custom Correct Elwha Valley; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Warning: Trail is closed due to the removal of Glines Canyon Dam. Contact the park for current status. Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 48 00.115, W 123 36.266

|

A quiet trail to a small backcountry campground on Lake Mills, this hike makes for a good leg stretcher on a rainy afternoon. It’s also the perfect place to watch the transformation of the Elwha River back to a wild and free-flowing waterway. The removal of the Glines Canyon Dam has begun, and soon Lake Mills will become a distant memory. Hike this trail to celebrate the restoration of a great river. |

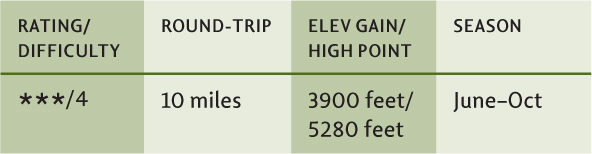

Dam to be removed on Lake Mills

NO DAM. GOOD!

For millennia the Elwha River ran wild and free. From its origins deep within the Olympic Mountains, the mighty waterway tumbled and flowed 45 miles to its outlet on the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Its legendary salmon runs fed the Klallam people. Hundreds of thousands of the anadromous fish, some weighing 100 pounds, made their way up the Elwha each year. But all that changed in 1911 when a dam was constructed just 5 miles up the river.

The Elwha Dam, the lower of two dams, was built without a fish ladder. Then in 1926 an upper dam was built at Glines Canyon. It, too, was constructed without a fish ladder. After thousands of years, the salmon runs of the Elwha ceased—a blow to a culture, an ecosystem, and a nation. The power generated from the dams is small, and in modern times used only by a local paper mill. To many citizens, conservationists, and anglers, the destruction of one of the greatest salmon runs in the state was not at all justified.

By the 1980s the country’s love affair with hydropower projects had begun to change. Many Americans realized that there were real costs involved with this so-called clean energy source. Those costs were degradations to our environment. A movement mounted to remove the two dams, and a wide consortium of the public protested the dams’ reauthorizations. Congress got involved in this contentious issue, resulting in the Elwha River Ecosystem and Fisheries Restoration Act of 1992, which authorizes the dams’ removal.

The act was a major victory for the river, salmon, the greater Olympic ecosystem, the Klallam people, and the country. It marked a major shift in policy. Now, after a decade of planning, public commenting, and review, the dams are coming down. Removal has begun and will continue for a few years. One hundred years after the mighty river was harnessed, it will once again run free.

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles follow US 101 west for 9 miles. At milepost 240, before the Elwha River Bridge, turn left onto Olympic Hot Springs Road (signed “Elwha Valley”). Follow this good paved road for 5.5 miles (entering Olympic National Park at 2 miles). At a sharp turn above the Glines Canyon Dam, turn left (use caution on this blind corner) onto a dirt road (signed “boat launch”). Proceed 0.2 mile to the trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

The Lake Mills Trail begins by the boat launch on this man-made body of water. As far as lakes go, Mills isn’t anything special. Still, many people have come to love it since its inception in 1927. They’ve paddled, fished, and admired snow-capped mountains reflecting in its dark waters. While many hikers eagerly anticipate the dam’s removal, a few will be lamenting the lake’s demise.

The real charm of this trail, however, is the forest it traverses. Mossy alder groves, a handful of madronas, and plenty of big old firs will greet you along the way. There are lots of creeks to cross too. After periods of heavy rainfall you may find that one or two test the waterproofing of your boots.

After a pleasant start along the lakeshore, the trail climbs almost a couple hundred feet above it. Enjoy some good lake views and then plunge back to the shoreline. Hop across a few more creeks, and at 1.9 miles come to a backcountry campsite. Proceed for another 0.1 mile to the trail’s end at a small bluff above crashing Boulder Creek. Retrace your steps, visualizing the trail running along a free-flowing river like Boulder Creek.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Across Lake Mills on the Whiskey Bend Road is the trailhead for the Upper Lake Mills Trail. Hike a short, steep 0.4 mile, losing 350 feet of elevation, to the lake’s inlet. Here, marvel at the delta that has formed due to the impounded river. A hidden waterfall on Wolf Creek near the trail’s terminus is worth snooping around for.

|

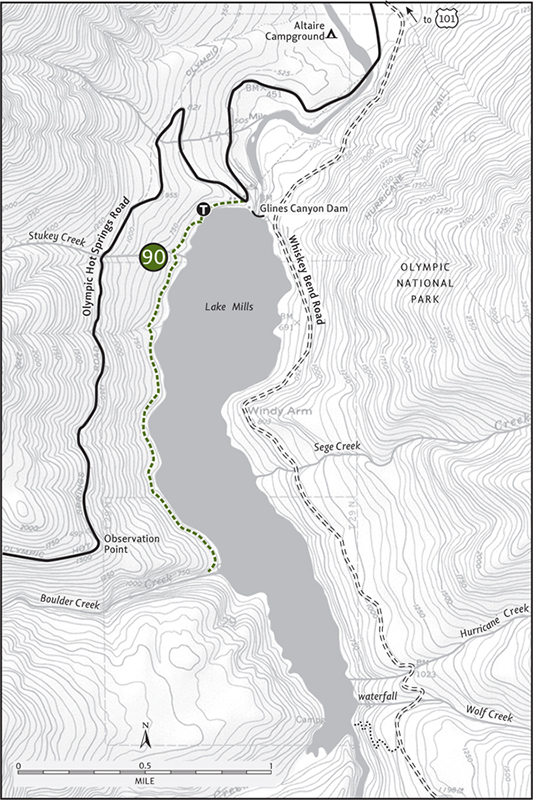

Happy Lake |

Maps: Green Trails Seven Lakes Basin–Mt Olympus No. 133S, Custom Correct Lake Crescent–Happy Lake Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Warning: Trail is now inaccessible due to road closure above Altaire Campground while Glines Canyon Dam is removed. Contact the park for latest road status. Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 47 59.005, W 123 37.540

You may have a hard time staying jovial on your way to Happy Lake. Reaching this subalpine lake requires a stiff climb up a high dry ridge. But once you crest Happy Lake Ridge, a smile is sure to come to your sweaty face. Open forest, quiet meadows, and heather parklands grace the way. Enjoy breathtaking views, too, of the sweeping Elwha Valley and the impressive snow and rock wall known as the Bailey Range.

View along Happy Lake Ridge

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles follow US 101 west for 9 miles. At milepost 240, before the Elwha River Bridge, turn left onto Olympic Hot Springs Road (signed “Elwha Valley”). Follow this good paved road for 8.7 miles (entering Olympic National Park at 2 miles) to the trailhead, located on the right.

ON THE TRAIL

Happy Lake was named by three pioneering bachelors extolling their emotional state in their femaleless society. The fishing must have been pretty darn good! The happy three are long gone, and many women have since graced the shores of this lovely little backcountry lake. But don’t expect much company of any kind on your trek. While the nearby Boulder Creek valley teems with hikers, Happy Lake remains quiet. You’ll probably have the whole place to yourself—happy?

Waste no time gaining elevation. Come near a small creek in 0.25 mile, the last reliable water until the lake. Cutting through thick carpets of salal, the trail next winds its way up Happy Lake Ridge. At 1.5 miles a small spring may be flowing; big trees and a brushy slope indicate its past irrigations. The climb then stiffens, huckleberry bushes and bear grass now lining the way. A small clearing is passed, providing a good view of Mount Carrie to the south.

After almost 3 miles of unrelenting climbing, the trail reaches the ridge crest (elev. 4500 ft). Now heading west along the ridge, enjoy much easier going, the trail ascending a small knoll before leveling out. At 3.5 miles come upon a stunning view spanning from Appleton Pass all the way to Obstruction Point. Hurricane Hill and Mount Angeles can clearly be seen in the east across the deep cut of the Elwha Valley.

Continue along a narrowing crest, taking in views both north and south. The ridge broadens again as its highest point is neared. Traversing subalpine forest and heather parkland, the way makes one final climb, topping out at 5280 feet after 4.5 miles. Consider walking up one of the adjacent knolls for excellent views; otherwise, head down the Happy Lake Trail, which takes off right.

Descending 400 feet through lovely subalpine country, the jovial tarn is reached in 0.5 mile. Situated in a small cirque, the grassy-shored lake is a happy sight. And hungry mosquitoes may be happy to see you. Consider visiting in fall, when the bloodsuckers are gone and the hillside is carpeted in crimson. As far as the fishing goes, it’s still pretty good.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

The Happy Lake Ridge Trail continues from its junction with the Happy Lake Trail for 5.2 miles to Boulder Lake (Hike 92). Amble just a little ways beyond the junction for some excellent views north into the Barnes Creek basin.

|

Boulder Lake |

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge No. 133S, Custom Correct Lake Crescent–Happy Lake Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Warning: Trail is now inaccessible due to road closure above Altaire Campground while Glines Canyon Dam is removed. Contact the park for latest road status. Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 47 59.210, W 123 39.115

Hike to an emerald lake in a subalpine setting. The trip is long, but the terrain is welcoming and the surroundings peaceful. Miles of magnificent old growth shade the way. Come in midsummer and enjoy a swim. Visit in late summer and reap a bounty of succulent huckleberries. Make the trip on a chilly autumn day and look forward to a hot-springs soak on the way out.

Aquamarine Boulder Lake—Boulder Peak in the background.

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles follow US 101 west for 9 miles. At milepost 240, before the Elwha River Bridge, turn left onto Olympic Hot Springs Road (signed “Elwha Valley”). Follow this good paved road for 10 miles (entering Olympic National Park at 2 miles) to its end and the trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

The first 2.3 miles of this hike are a drag, utilizing a paved road long-closed by the Park Service. It was a prudent move to cut down on crowding and problems at the popular Olympic Hot Springs, but it makes for a boring approach. Bicycles aren’t allowed (even if they were, three washouts would prove difficult to negotiate), so you’ll just have to suck it up. I usually hike this section in running shoes and change into boots when the real trail starts, ditching my shoes for the return.

After plodding the pavement, arrive at a junction at a former car campground, now a popular backcountry camping area, Boulder Creek Camp. The trail left goes a short distance to a series of hot-spring pools tucked on ledges above crashing Boulder Creek. Avoid them in the summer—they’re crowded and probably won’t get the health inspector’s thumbs-up. Besides, it’s hot in the summer—what’s the point? In the off-season, however, these pools, the only natural soaking area in the Olympics, are really inviting.

For Boulder Lake, continue right, climbing to well-used campsites and the start of real trail. Walk a gentle short mile through cool and inspiring ancient forest to another junction, and take the trail to the right (the left-hand trail heads to Appleton Pass, Hike 93). Angling along a slope crowded by coniferous giants, the trail climbs at a moderate grade, allowing you to absorb the beauty and tranquility of your surroundings. Boulder Creek’s crashing and thrashing fades into the distance. Silence.

At about 4.5 miles the trail approaches North Fork Boulder Creek and steepens, making a final push to the lake. At 5.9 miles a junction is reached. Boulder Creek is a pebble’s throw away to the left (the right-hand trail heads to Happy Lake Ridge; see Hike 91).

Cross marshy meadows and reach the lake, which is perched in a semi-open bowl at the base of 5600-foot Boulder Peak. Inviting shoreline ledges that harness the sun’s warmth, perfect for a nap or lunch break, can be found just a short distance to the south. Enjoy the green hue of the lake’s waters, and enjoy the silence of the surrounding environment. Well, not quite silent. Chattering chickarees, busy nuthatches, flittering dragonflies, and surface-breaking fish add some commotion. But it’s peaceful just the same.

|

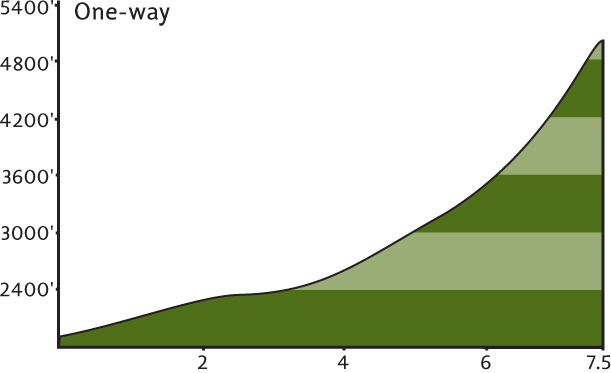

Appleton Pass |

Maps: Green Trails Elwha North–Hurricane Ridge No. 133S, Custom Correct Seven Lakes Basin–Hoh; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Warning: Trail is now inaccessible due to road closure above Altaire Campground while Glines Canyon Dam is removed. Contact the park for latest road status. Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 47 59.210, W 123 39.115

An arduous hike to one of the most spectacular mountain passes in the Olympics—Appleton Pass sits a mile high on the Elwha–Sol Duc divide. Offering glimpses of peaks, forested valleys, and thousands of acres of wilderness in both watersheds, Appleton Pass is a remote outpost in the heart of the Olympics. On the demanding journey there, encounter resplendent meadows, primeval forest, and captivating cascades. But even if you’re not up for this laborious trip, just a few miles along this trail still has its rewards.

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles follow US 101 west for 9 miles. At milepost 240, before the Elwha River Bridge, turn left onto Olympic Hot Springs Road (signed “Elwha Valley”). Follow this good paved road for 10 miles (entering Olympic National Park at 2 miles) to its end and the trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

Start off on a long-abandoned section of the Olympic Hot Springs Road. The paved but rapidly crumbling road travels 2.3 miles to a junction at Boulder Creek Camp. The Olympic Hot Springs are just a short distance to the left, and you may want to consider soaking in them after your return. But skip the idea in the summer—you won’t find space, and your aching body doesn’t need to fight off a viral attack while it’s recovering.

Continue right, through campsites to the start of bona fide trail. At 0.8 mile come to a junction for Boulder Lake (Hike 92). Continue left through imposing ancient firs, cedars, and hemlocks. The forest has a dry feel, as Mount Appleton and the Bailey Range create a bit of a rainshadow effect here on their eastern sides.

About 0.75 mile beyond the junction, the trail crosses North Fork Boulder Creek, which is prone to jumping its channel. You may have to negotiate a few washed-out areas before actually crossing the creek.

Picturesque Oyster Lake at Appleton Pass—Mount Appleton in the background

A PRESSING TRIP

In February 1890, having made camp at several spots along the lower Elwha River since December, James H. Christie led a group of five rough and ready men, a couple of dogs, and a pack of mules on an arduous three-month journey across the Olympic Mountains. Christie’s ambition to explore the last of the uncharted mountain ranges in the continental United States was met with much interest and enthusiasm in the new state of Washington.

Funded by the Seattle Press newspaper, Christie’s voyage was named the Press Expedition, and upon the party’s emergence at Lake Quinault in May 1890, it became the first successful European American north-south crossing of the Olympics.

Many of the place names that dot the Olympics today were bestowed by Christie and company: Mount Ferry (for Washington’s first governor), Mount Seattle (after the city), Mount Barnes (for an expedition member), the Bailey Range (for the publisher of the Seattle Press), and Mount Christie (for Christie himself, no less).

An objective of many modern-day Washington backpackers is to hike a route that roughly follows the Press Expedition’s original course: a 45-mile journey from Whiskey Bend up the Elwha over the Low Divide and out the North Fork Quinault River. What took the intrepid Press Party over three months to complete is now—thanks to manicured trails—easily covered in three to five days.

In another 0.5 mile two short side trails lead left to pretty little Boulder Falls, a series of cascades set in a mossy ravine. This is a good destination for hikers not intent on going all the way to Appleton Pass. A handful of swimming holes beneath the lower falls may be tempting, but remember, they ain’t no hot springs!

Beyond the falls, the trail crosses the creek and climbs more steeply. Traversing a deep rugged valley, forest cover thins, allowing previews of what lies ahead. Bubbling springs and copious huckleberry bushes may entice you to abandon your strenuous march.

After about 5.5 miles the trail enters an open basin, getting rougher while the views get better. Look back at Lizard Head Peak; Mount Appleton looms above. Dazzling wildflowers paint the basin in reds, purples, and yellows, and numerous creeks tumble down the rugged encircling slopes.

The trail makes a few steep and sweeping switchbacks through clumps of mountain hemlock and sprawling meadows, finally arriving at the 5050-foot pass after 7.5 grueling miles.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Oyster Lake lies a short distance to the left and 100 feet higher, reached by a well-defined way path. If time and energy permit, wander beyond the lake to some of the most amazing views in the Olympics.

Lake Crescent

With over 5000 surface acres, Lake Crescent is the largest lake within the Olympic Mountains and is among the largest natural bodies of freshwater in western Washington. Arched like a crescent, the 9-mile-long lake is known for its crystal clear waters and stunning mountain reflections. A couple of pockets of private cabins (grandfathered in after the park’s creation) line the lake, but the majority of shoreline acreage is undeveloped and managed by Olympic National Park.

Hiking options in the Lake Crescent area range from easy lakeshore wanderings to steep grunts up surrounding ridges and peaks. Unfortunately, while the lake may evoke a feeling of tranquility, the constant hum of vehicles on US 101 disrupts the peace. Still, it’s possible to escape this noisy intrusion by hiking along a babbling creek—or along the lakeshore or an adjacent ridge top when strong winds whistle a more harmonious hymn.

Lake Crescent is a great place to set up a base camp for exploring adjacent trails and those located in the nearby Sol Duc Valley. A fine national park campground complete with beach and boat launch can be found at Fairholm on the lake’s western end, while the Lake Crescent Lodge and Log Cabin Resort offer cushier alternatives. And watch out: the lake’s alluring waters may just have you packing your kayak along with your trekking poles.

|

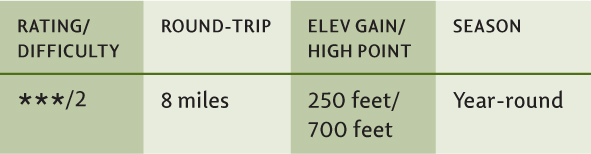

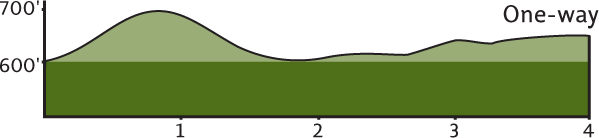

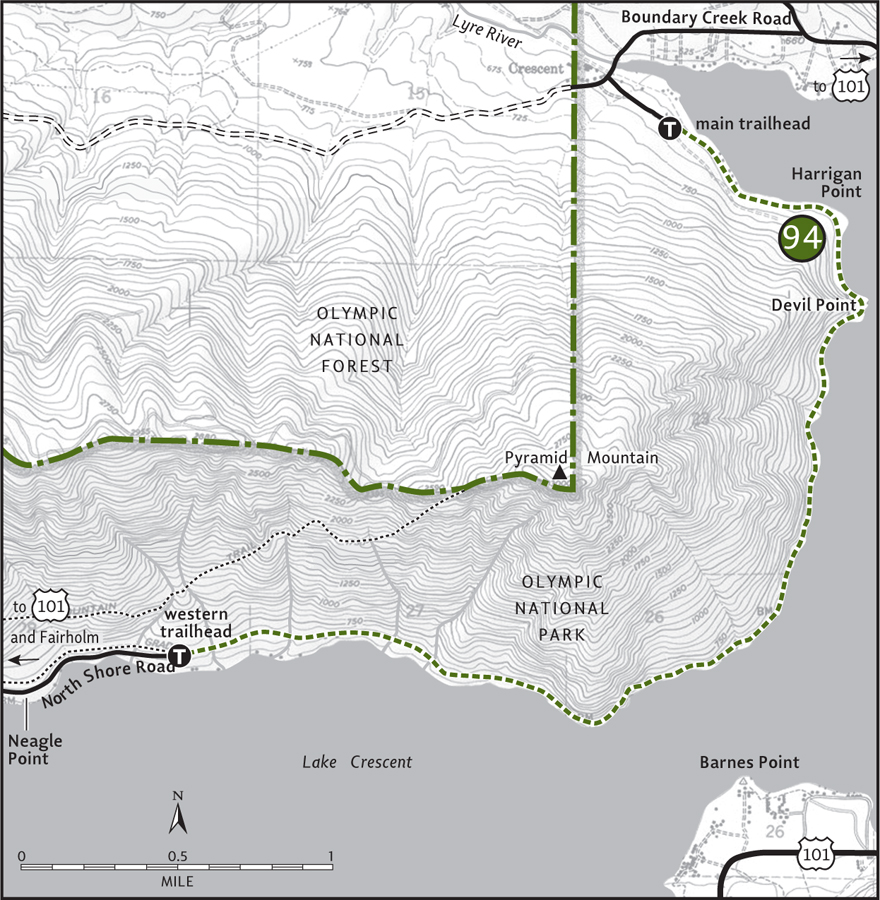

Spruce Railroad Trail |

Maps: Green Trails Lake Crescent No. 101, Custom Correct Lake Crescent–Happy Lake Ridge; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs permitted on leash; GPS: east trailhead N 48 05.597, W 123 48.151, west trailhead N 48 04.062, W 123 49.534

|

Hop aboard the Spruce Railroad Trail for a scenic and historic hike along the sparkling shores of massive Lake Crescent. For 4 nearly flat miles you’ll saunter along one of Olympic National Park’s most alluring natural features. Nine miles long, over 600 feet deep, and surrounded by steep ridges and peaks, Lake Crescent seems more like a fjord. With a microclimate of warmer and drier conditions than areas just a few miles away, this trail is a good hiking choice on an overcast afternoon. |

GETTING THERE

From Port Angeles follow US 101 west for 17 miles to the Olympic National Park boundary. Turn right onto East Beach Road (signed “Log Cabin Resort, East Beach”). Follow this narrow paved road for 3.2 miles. Just beyond the Log Cabin Resort, turn left onto Boundary Creek Road (signed “Spruce Railroad Trail”). Follow it for 0.8 mile to the eastern trailhead. Privy available.

Bridge over the Punchbowl on the Spruce Railroad Trail

ON THE TRAIL