southwestern washington

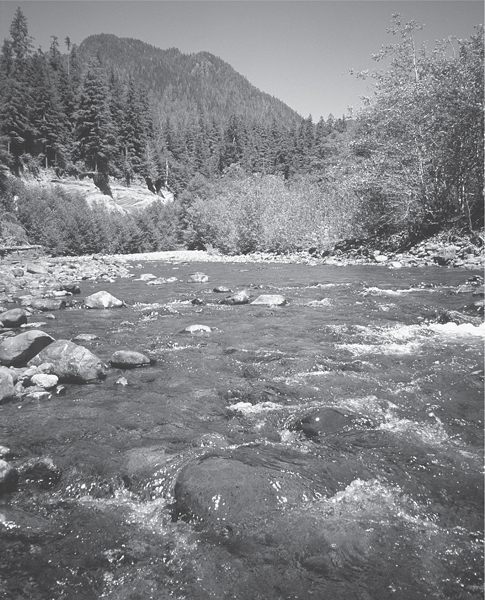

Crashing cascade on the Big Creek Trail

The Rain Forests

One of the Olympic Peninsula’s most famous attractions, the temperate rain forest offers one of the most unique hiking experiences in the country. Such forests are found only in Chile, New Zealand, and the Pacific Northwest, and those of the Olympic National Park are perhaps the most accessible. Good trails lead to and through all of the major rainforest valleys.

Here you’ll hike among some of the largest living organisms in the world. While tropical rain forests rank supreme in biodiversity (number of species), the temperate rain forests of the Olympic Peninsula contain the highest amount of biomass (living matter) on the planet. Giant conifers cloaked in epiphytes and growing upwards of 300 feet dominate a saturated forest floor shrouded in mosses, ferns, horsetails, and ground pines. The damp, heavy air of the rain forest teems with spores. Hike into this special environment and you can feel the forest breathe. Sense its pulse. Grasp its fortitude.

And while parts of this region can receive over 200 inches of rainfall a year, it’s not unusual to be kissed by the sun while hiking deep into the Olympic rain forest. Days are often dry in August and September—the dry season—and it’s not uncommon to get a reprieve from the rain in the middle of the winter. Pack sunglasses with your poncho and waterproof those boots; there are miles of trails to be explored in this fascinating bioregion.

|

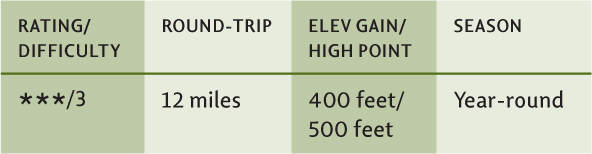

Bogachiel River |

Maps: Green Trails Spruce Mountain No. 132, Custom Correct Bogachiel Valley; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited at national park boundary (at 1.5 miles); GPS: N 47 52.933, W 124 16.503

The Bogachiel River snakes through Washington’s forgotten rain forest. No main roads run along this major Olympic river, nor penetrate its wild valley. There are no visitors centers here either. No interpretive trails or developed campgrounds amid the towering spruce and fir. There’s nothing fancy here at all—just a quiet backcountry trail through pure rainforest wilderness.

GETTING THERE

From Forks travel south for 5 miles on US 101. Turn left (east) onto Undie Road, located directly across from the entrance to Bogachiel State Park. Follow this road for 5.6 miles to a gate and the trailhead (the last 2 miles are unpaved and during heavy periods of rain are prone to flooding and developing giant mud holes). Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

Your first impression of the Bogachiel River Trail may have you wondering, “I thought this was a wilderness trail through old-growth rain forest.” It is—just give it a couple of miles. The trail begins in a dark forest of second growth. It was logged during the 1940s in the name of national defense.

Descend on a muddy track to Morganroth Creek, where a fallen old-growth giant has been converted into a bridge. Just beyond, the Ira Spring Wetland Loop leads left to a marshy area. This trail rejoins the main trail in 1.2 miles, offering a variation on your return. The main trail continues right, intersecting then utilizing an old road bed for some level and easy strolling.

At 1.5 miles come to the national park boundary. Pooches are not permitted beyond this point. Along rich bottomlands the trail brushes up against the river. At 2.5 miles negotiate a steep bluff (with the help of a rope) to skirt an area claimed by the river. Drop back down to river level and get your feet wet again hopping across Mosquito Creek. Big trees finally appear (I told you it gets better). Despite light use, the trail is in remarkable shape, thanks in large part to the tireless work of the Washington Trails Association. But while only a handful of hikers trek up this valley each year, the elk that pass through are legion. Keep your eyes out for these elegant beasties.

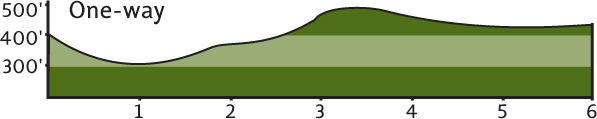

Giant Sitka spruce along the Bogachiel River

Ancient giants dwarf you as you continue up the trail. Except for the river’s soothing churn and sweet serenades from resident wrens, the primeval forest is quiet. Lichens drape overhead. Fern boughs burst open from the forest floor. Dew-dripping moss clings to everything. Only the glaucous sheen of alder bark breaks the deep green of the rain forest.

After 6 miles of peaceful passage, you’ll come to a junction with the Rugged Ridge Trail and a most inviting riverside camping area. This is a good spot to turn around, or if inclined, spend the night. During low water flows, venture out onto the gravel banks of the river. During downpours admire the torrents from the elevated embankment.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

The Bogachiel River Trail continues deep into the Olympic backcountry for 18 more miles. Wander up the Rugged Ridge Trail to Indian Pass for some real solitude. Car-camp at Bogachiel State Park for a cushy night in the rain forest. Don’t forget the tarps!

|

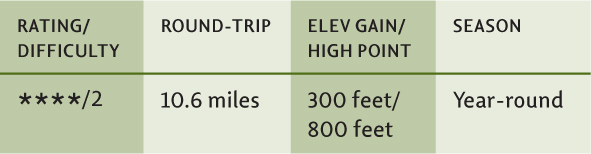

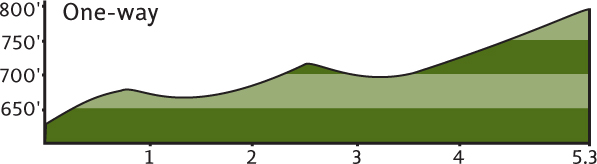

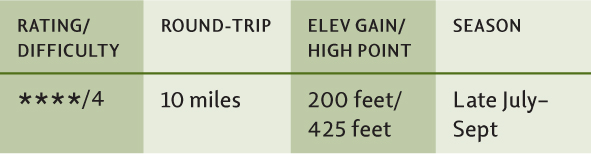

Hoh River-Five Mile Island |

Maps: Green Trails Seven Lakes Basin–Mt Olympus Climbing No. 133S, Custom Correct Seven Lakes Basin–Hoh; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. National park entry fee required; GPS: N 47 51.580, W 123 56.023

|

The most famous of all the Olympic rain forests, the Hoh is one of the busiest places in Olympic National Park. A visitors center and a couple of well-groomed nature trails attract bus loads of admirers from Seattle to Seoul, Boston to Berlin. And its not just camera-toting tourists that invade this valley; pan-toting backpackers and caribiner-clanking climbers flock here too. The Hoh River Trail also provides access to Mount Olympus and the High Divide. But who can blame all of these people for coming here? The Hoh rain forest truly is one of the world’s most spectacular places. |

GETTING THERE

From Forks travel south on US 101 for 12 miles to the Upper Hoh Road. (From Kalaloch head north on US 101 for 20 miles.) Head left (east) on the Upper Hoh Road for 18 miles to its end at a large parking lot, visitors center, and trailhead. Water and restrooms available.

ON THE TRAIL

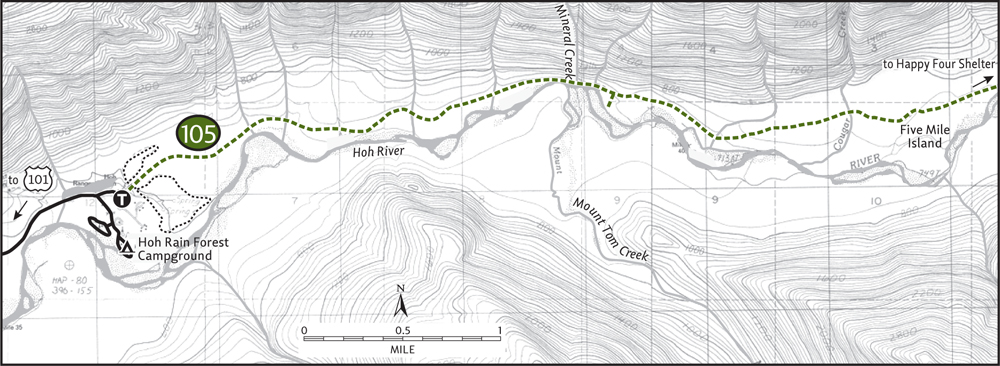

While the Hoh rain forest is a busy place, most hikers visit during the summer months and on autumn weekends. Come in the spring or even winter and experience a valley more sedate. Besides, with fewer people in the off-season, chances are good of witnessing members of the resident elk herd. But even if you end up hitting the trail on a busy day, the crowds thin out dramatically after only a couple of miles.

The hike to Five Mile Island is far enough to experience the old-growth grandeur and pure wildness of this valley, yet close enough that it can be done by most hikers, young and old. The trail is impeccably groomed, and the way virtually level, with minimal elevation change. Five Mile Island, with its wide grassy banks along the mighty rainforest river, was designed for whiling the afternoon away.

Start by following the paved Hall of Mosses Trail for 0.2 mile to a junction. Now on bona fide tread begin your journey through this valley of primeval forest. A cacophony of birdsong from wrens, nuthatches, woodpeckers, chickadees, and thrushes can be heard over the distant hum of the river. Pass by colonnades of spruce and under awnings of moss-cloaked maples. Licorice ferns and club mosses cling to overhanging trees like holiday decorations on New York’s Fifth Avenue. And while the surroundings are lush, the understory is fairly open. Browsing elk keep the shrubs and bushes well trimmed.

Hoh rain forest

In 1 mile get your first unobstructed view of the river. Gaze out to the High Divide and snow-capped Mount Tom, a peak on the Olympus massif. Pass the Mount Tom Creek Campsite at 2.3 miles; then climb above the river, catching glimpses of deep emerald pools below. Cross Mineral Creek by a lovely cascade. Five minutes later another cascade delights. At 2.9 miles come to a junction with the Mount Tom Trail. If you’d like, follow this path right 0.25 mile to open gravel bars and spectacular valley views.

Veering away from the river, the main path continues. Traverse impressive stands of Sitka spruce and at 4 miles come to the Cougar Creek cedar grove. Stand in awe beneath these trees, older than the great cathedrals of Europe—and just as inspiring. At 5.3 miles arrive at Five Mile Island. Formed by river channels, the island is an inviting grassy bottomland graced with maple glades. Sit by the churning river and enjoy views up the valley all the way to Bogachiel Peak. If it’s raining, the nearby Happy Four Shelter (0.5 mile farther) will provide cover for your lunchtime break.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

The Hoh Campground at the trailhead is a delightful place to spend the night. By all means check out the two adjacent nature trails and the visitors center to gain a better appreciation of this fascinating corner of the planet.

|

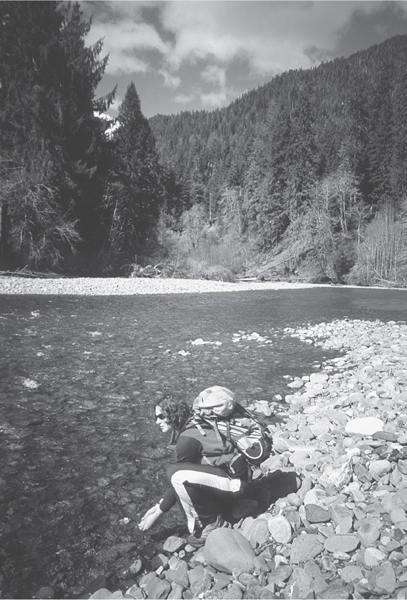

South Fork Hoh River-Big Flat |

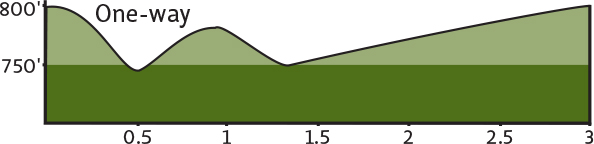

A hiker heads out onto the gravel bars of the Big Flat on the South Fork of the Hoh.

Maps: Green Trails Mt Tom No. 133, Custom Correct Mount Olympus Climber’s Map; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited; GPS: N 47 47.957, W 123 57.267

|

Hikers from around the globe find their way to the Hoh rain forest. After all, it is world famous. But if your idea of experiencing the Olympic rain forest is sans bucketloads of people, cast your attention to the Hoh’s little known South Fork. Local fly fishermen are familiar with this wild and lonely valley, but most hikers aren’t. Getting to the trailhead can be confusing, but the hike is easy and not very long. The payoff is solitude. |

GETTING THERE

From Forks travel south on US 101 for 14.5 miles. Drive 2 miles beyond the Hoh River Bridge and turn left onto the Clearwater Road at milepost 176 (signed “Clearwater–Hoh State Forest”). Proceed on this paved road for 6.9 miles to a junction. Turn left onto Owl Creek Road (signed for the South Fork Hoh Trail and campground). In 2.3 miles bear right onto Maple Creek Road, following signs for the campground. After 5.4 miles cross the South Fork Hoh River and pass the campground entrance. Continue for another 2.3 miles, bearing right at an unmarked junction. In 0.5 mile the road ends at the trailhead (unsigned as of spring 2006).

ON THE TRAIL

The trail starts in Washington State Department of Natural Resources (DNR) land that has been intensively logged over the decades. Through scrappy trees choked in mosses, drop down to a flat outwash area. Cross numerous streams in various stages of flow and after 0.5 mile reach the national park boundary. Now we’re talking trees—real old trees, real big trees.

Pass a monstrous Sitka spruce recently laid to rest by a winter storm. Climb onto a bench, pause and look around in bewilderment. Do you feel small? Gargantuan Doug-firs, western hemlock, and Sitka spruce tower above you like skyscrapers in an ecotopian Manhattan. At 1 mile you’ll come to a crashing creek that may prove tricky to cross after a heavy rain.

Continuing under a canopy of ancient giants, the trail drops to a lush bottomland known as Big Flat. At 1.3 miles you’ll come to a backcountry campground. A side path diverts right, leading to open gravel banks on the South Fork Hoh. The main trail continues left through grassy swales and alongside colonnades of maples. At 2.25 miles, past more impressive spruce trees, the trail finally greets the river.

Soon a large washout is encountered, but the trail has been rerouted around it. Cross a lazy side creek on a sturdy log. Ten minutes beyond, about 3 miles from your start, the trail abruptly ends. The South Fork in one of its winter huffs lopped off a huge part of its bank, taking a good piece of trail with it. More tread can be picked up farther upstream, but some difficult bushwhacking is required to get to it. Instead, plop down on the nice grassy bank before you and let the solitude serenade you.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

The DNR South Fork Hoh River Campground located downstream from the trailhead has a handful of inviting sites right on the river.

|

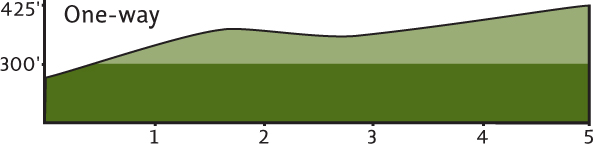

Queets River |

Maps: Green Trails Kloochman Rock No. 165, Custom Correct Queets Valley; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. Queets River ford required, only safe during low flows. GPS: N 47 37.469, W 124 00.856

|

Big trees, a wilderness valley flourishing with wildlife, and no crowds. The peninsula’s wildest rainforest valleys are up the Queets River, and many a hiker has never ventured into this enchanting corner of Olympic National Park. The main deterrent is accessibility, both to and on the trail. The gravel 14-mile Queets River Road can often be agonizing to drive. And once you reach the trailhead, you’ll find there’s no bridge over the river! This keeps more than a handful of adventurers from ambling up the trail. But if you persist you’re guaranteed a lonesome journey. |

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam travel north on US 101 for 51 miles (From Forks travel south on US 101 for 51 miles). Turn right onto paved FR 21 and proceed for approximately 8 miles, turning left onto FR 2180. Continue for about 2.0 miles, turning left onto FR 2180-011. Follow this road 1.5 miles to Upper Queets Road. Turn right and proceed 3.0 miles to road end and trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

From the trailhead kiosk look down the steep riverbank to see what lies ahead: the Sams River rushing into the Queets. Both need to be forded if you’re intent on exploring this wild valley. The crossing can be intimidating, but in the drier months of August and September the rivers are usually only knee-deep. A set of old running shoes and sturdy trekking poles should help get you across safely. Do not attempt to cross early in the season or after heavy periods of rain. Remember, too, that on hot days the water will be higher on your return due to the melting snow feeding the river. If it looks unfavorable, head over to the Sams River Trail instead (Hike 108).

Once you’ve crossed the wide river, you’ll get to experience a wilderness Olympic valley the way it should be experienced—crowds in absentia. Giant firs, towering spruce, and humongous hemlocks 200-plus feet tall and several hundred years old humble your stature and status. Moss-draped maples and lichen-blotched alders line the trail. Boughs of ferns 4 feet tall crowd the understory.

Although the Queets is in essence a wilderness, it has experienced man’s presence for centuries. Native Americans long hunted this remote valley. A few hardy pioneers homesteaded it. At 1.6 miles a dilapidated barn is evidence of the latter’s tenure.

The hike begins with a ford of the Queets River.

From this small clearing, Kloochman Rock can also be seen peeking above the remote valley. At 2.3 miles a short side trail leads left 0.25 mile to one of the biggest and oldest Douglas-firs in the world. With a trunk 14 feet around, this tree began its life sometime around the first millennium.

Through lush bottomlands the Queets River Trail heads deeper into the heart of the Olympic Mountains. At 4 miles a side trail leads right (requiring a ford) 2 miles to Smith Place, the remains of an old hunting cabin.

The main trail continues left, arriving at Spruce Bottom Camp at 5 miles. The bottomlands and gravel bars here make a nice destination for day hikers. Sit and enjoy the solitude and quiet, interrupted only by the soft rippling of the river and the frantic chirping of passing dippers.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

A short distance beyond Spruce Bottom, a side trail leads right, fording the Queets to reach Smith Place. Continue on the old trail for 1 mile to the truly remote rainforest river, the Tshletshy. Backtrack to Smith Place and return to the main trail via the primitive trail following the Queets’s east bank (this route requires a ford). The main Queets River Trail can also be followed upriver for another 10 miles, where it peters out near Pelton Creek.

|

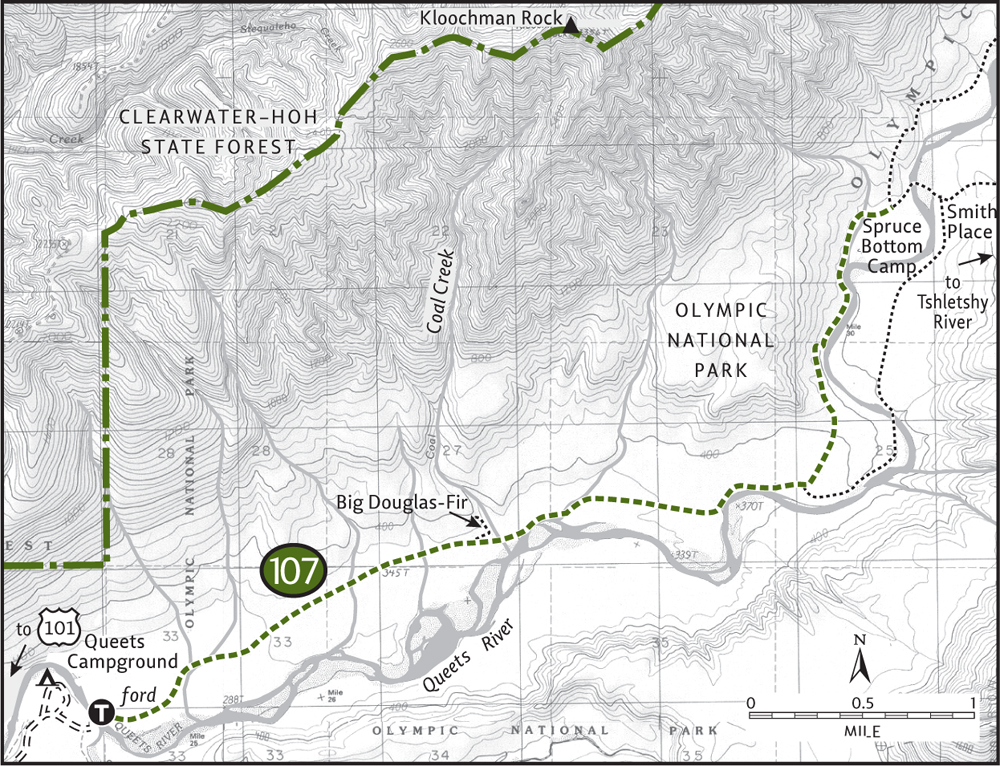

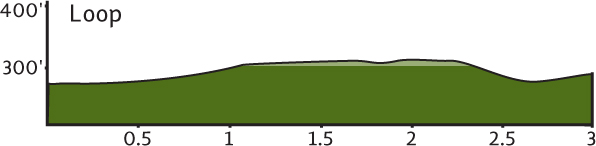

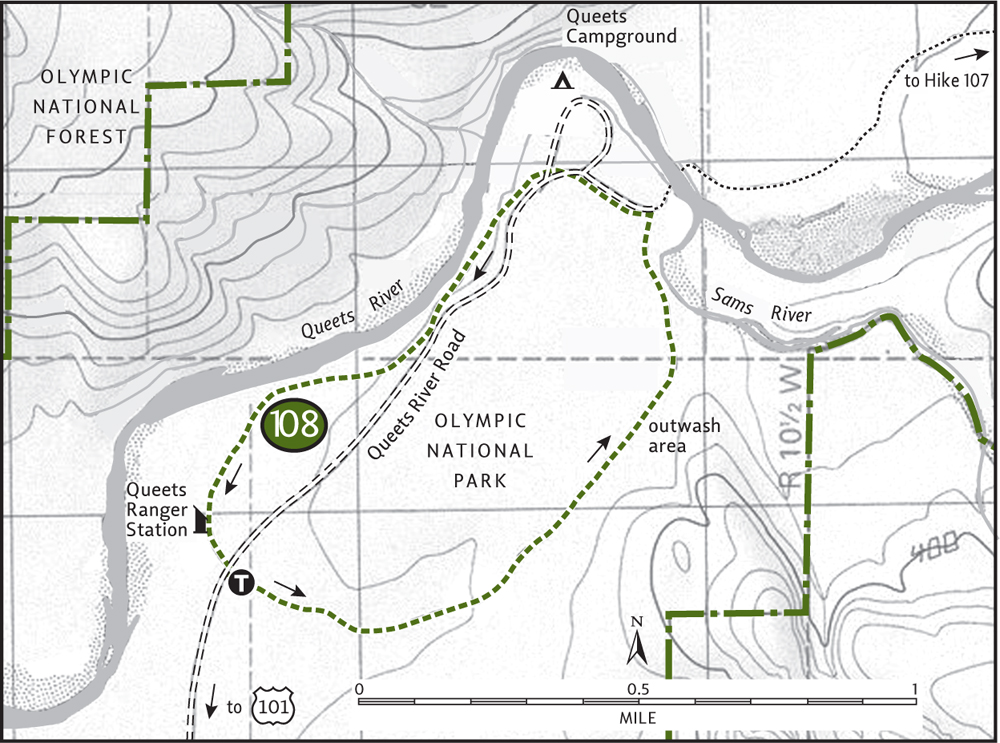

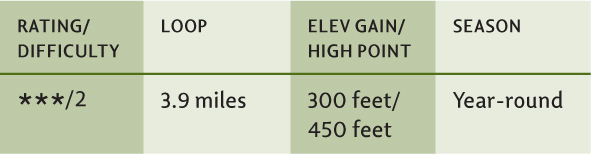

Sams River |

Maps: Custom Correct Queets Valley; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. GPS: N 47 36.985, W 124 01.924

|

Enjoy an easy loop in the Queets River valley without having to ford the river. Saunter along an open bank above the wild Queets, hike under some of the largest spruce trees in the park, and look for resident elk while traversing old homestead farms. The Sams River Loop is ideal for introducing children to the rain forest. Unlike nature trails at the Quinault and Hoh, you’ll have this entire living classroom for yourselves. |

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam travel north on US 101 for 51 miles (From Forks travel south on US 101 for 51 miles). Turn right onto paved FR 21 and proceed for approximately 8 miles, turning left onto FR 2180. Continue for about 2.0 miles, turning left onto FR 2180-011. Follow this road 1.5 miles to Upper Queets Road. Turn right and proceed 1.7 miles to the Queets Ranger Station. Park here; the trail begins across the road.

ON THE TRAIL

On soft tread frilled with mosses and oxalis, the trail begins its journey across a lush bottomland. This section of trail is often wet and muddy. Pass by wetland pools teeming with crooning frogs. At 0.3 mile come to a collapsed bridge at a channeled creek. Crossing is possible on a nearby fallen tree, but use caution.

Just beyond the creek is the first of several homestead clearings. Blackberry bushes and apple trees are all that remain. Between the melodic chirps of feasting birds, listen to the voices in the wind speak of the hardships and joys of living in the rain forest. Pick up tread again across the meadow in a grove of mossy maples.

A large outwash area is encountered in 1 mile. You may have to do some creek-channel hopping. Soon, the trail comes upon the churning Sams River. Take time to walk out on its wide gravel bars. Enjoy views of Kloochman Rock and surrounding ridges cloaked in deep greenery. Look for elk track etched into the sand.

Now climb a small bluff flanked with giant spruces that reach straight for the clouds. At 1.5 mile you’ll come to the Queets River Road and the trailhead for the Queets River Trail. Turn left on the road, pass the campground entrance, and pick up the Sams River Loop once again.

The Sams River flows into the Queets.

This half of the loop spends most of its time high on a bluff along the Queets. Scan the lofty conifers that embrace the river for perched eagles and kingfishers. Inspect trailside snags for industrious woodpeckers. Listen for owl hoots coming from the dark forest.

Continue along the river to another large homestead clearing. Elk evidence is everywhere, from droppings and tracks to flattened clumps of grass. Accessible gravel bars along the river, perfect for lounging and feet-soaking, can be found at the clearing’s edge. The trail continues through a stately maple glade, delivering you back to the ranger station at 3 miles.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

The primitive and quiet car campground at the end of the Queets River Road makes for a cushy night out in this wild rainforest valley. Bring your own water, or filter from the river.

|

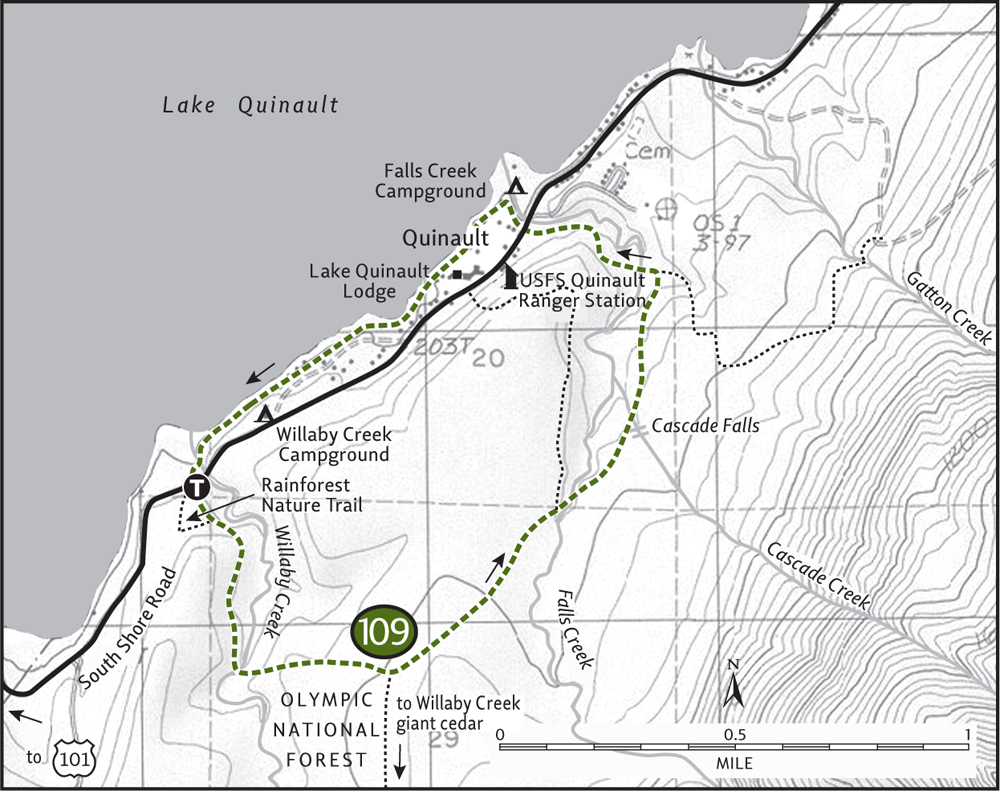

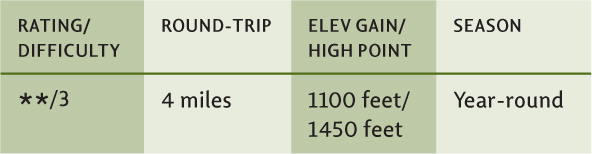

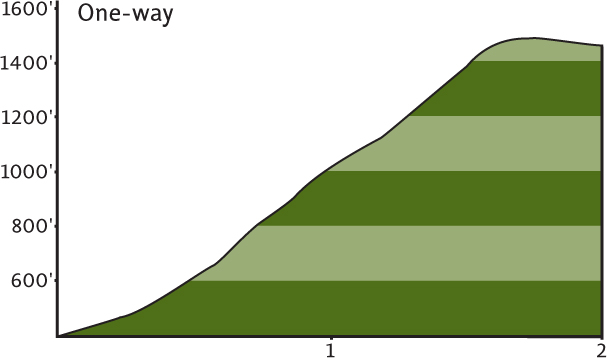

Quinault National Recreation Trails |

Maps: Green Trails Lake Quinault No. 197, Custom Correct Quinault–Colonel Bob; Contact: Olympic National Forest, Pacific Ranger District, Quinault, (360) 288-2525, www.fs.fed.us/r6/olympic; Notes: Northwest Forest Pass required. Dogs should be leashed. Storms in December of 2007 severely damaged road and trails in the Quinault Valley; check with ranger on current status; GPS: N 47 27.594, W 123 51.728

|

The Quinault National Recreation Trail system offers a mélange of hiking options to choose from. With nearly 10 miles of well-maintained interconnecting trails, your choices are as varied as spring wildflowers on these popular paths. Trails lead from campgrounds and a historic lodge to waterfalls, cedar bogs, monster trees, and along crystal-clear creeks and a scenic lakeshore. Spend a half day or half a week exploring this delightful area. The Rainforest Lake Loop is one suggestion. Feel free to expand, contract, or combine it with other trails. |

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam travel north on US 101 for 35 miles. Turn right (east) onto the South Shore Road, located 1 mile south of Amanda Park. Proceed on this road for 1.3 miles to a large parking area signed “Rainforest Nature Trail Loop.” Water and restrooms available.

ON THE TRAIL

Step into the Quinault rain forest and immediately be propelled into a world of primeval beauty. Start your journey under a canopy of towering, emerald giants: ancient Sitka spruce, western red cedar, and western hemlocks that were mere saplings when Christopher Columbus set sail for the Americas.

The Quinault Valley left a deep impression on president Franklin D. Roosevelt when he visited here in 1937. It inspired him to protect a good chunk of the adjacent lands within a new national park. The Quinault rain forest, however, has remained within the national forest. But it’s managed for recreation and wildlife, not timber production.

From the trailhead the well-groomed path passes a colossal Doug-fir to emerge on a high bank above Willaby Creek. Search the sparkling creek waters for salmon. Gaze up at the towering forest canopy for eagle nests. Then turn right and begin your journey into the past. At 0.25 mile is a junction; a short nature trail heads right, returning to the parking lot.

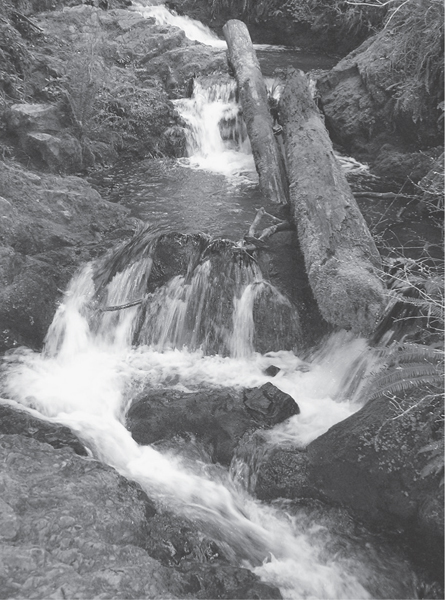

Cascades on Cascade Creek—Quinault National Recreation Trail

Continue on the main path, crossing Willaby Creek at about 0.5 mile. A half mile farther you’ll reach another junction. The trail to your right travels 1.7 miles and climbs over 1000 feet to the Willaby Creek giant cedar. A ford over Willaby Creek is necessary and can be difficult in high water.

The loop continues forward to a cedar bog bursting with pungent patches of skunk cabbage. Traverse this saturated landscape via a boardwalk and come to another junction at 1.8 miles. The trail to your left heads 0.6 mile to the Quinault Lodge; proceed right instead. Cross Falls Creek, and after 0.5 mile of gentle climbing, cross Cascade Creek at lovely Cascade Falls. Admire the tumbling waters and then carry on. At 2.4 miles turn left at a junction (the right trail goes to Gatton Creek). Span Falls Creek again, climb a little, and then drop back down to reach the South Shore Road at 2.8 miles.

Cross the road, stop to admire Falls Creek Falls, skirt a campground, and then come to Lake Quinault, one of the largest bodies of water on the Olympic Peninsula. Close the loop by following the lakeshore for 1 mile, passing quiet coves, humble cabins, and the majestic 1926 Lake Quinault Lodge. In times of heavy rainfall, this section of trail is prone to inundation. If that’s the case, return via the South Shore Road, or head up the Lodge Trail and retrace some of your route. The forest may be ancient, but this hike never gets old.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

From the Forest Service’s Quinault Ranger Station it’s a 3-mile one-way hike to the world’s largest Sitka spruce via the quiet Gatton Creek Trail. On the north shore of Lake Quinault the 0.5-mile Maple Glade and 1.3-mile Kestner Homestead Loop trails make great rainforest strolls and are kid-friendly. A number of car campgrounds on Lake Quinault make ideal base camps for exploring the region.

|

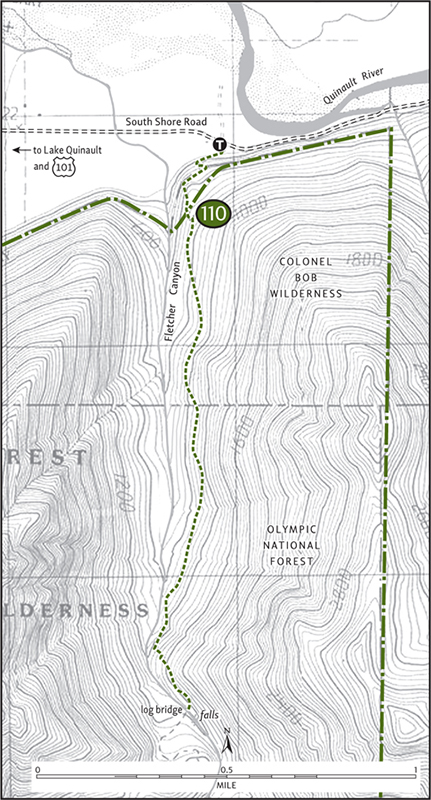

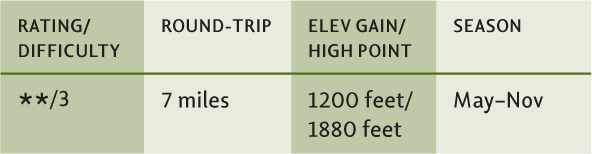

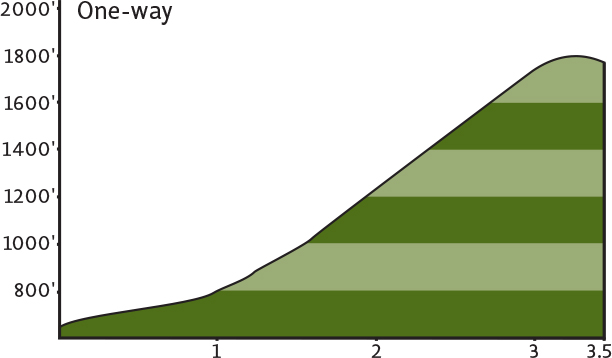

Fletcher Canyon |

Maps: Green Trails Mt Christie No. 166, Custom Correct Quinault–Colonel Bob; Contact: Olympic National Forest, Pacific Ranger District, Quinault, (360) 288-2525, www.fs.fed.us/r6/olympic; Notes: Storms in December of 2007 severely damaged roads and trails in the Quinault Valley; check with ranger on current status; GPS: N 47 31.700, W 123 42.395

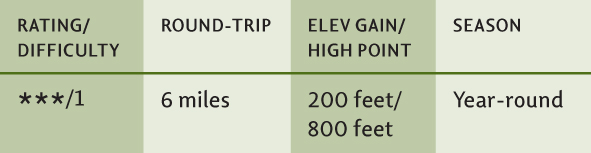

|

Venture up a deep and dark canyon into a lonely corner of the 11,961-acre Colonel Bob Wilderness. The hike is short, but steep in places, and the terrain can be rough. But what will you receive for your sweat and toil? An excellent chance of observing a few of the wild denizens of this rugged rift in the Quinault Ridge. Stay alert for elk, cougar, bear, and perhaps even an endangered marbled murrelet while exploring this remote part of the Quinault rain forest. |

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam travel north on US 101 for 35 miles. Turn right (east) onto the South Shore Road, located 1 mile south of Amanda Park. Proceed on this road for 12 miles (passing the Forest Service’s Quinault Ranger Station at 2 miles). The trail begins at the end of a small spur on the south side of the road. If the spur is flooded (often in winter), park instead on the north side of the South Shore Road.

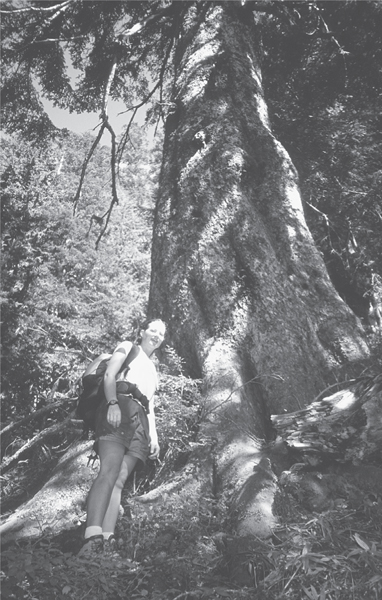

Big trees dwarf a hiker in Fletcher Canyon.

ON THE TRAIL

The trail starts by an apartment-size boulder housing an array of ferns and lichens. Ignore the kiosk sign that says “Col Bob Trail 4 miles.” The trail beyond the 2-mile mark has long been abandoned. Overgrown to jungle proportions, even Sasquatch now avoids it. Immediately start climbing on a sometimes steep, sometimes rocky route. Numerous creeks cross the trail, making it a challenge if you’re intent on keeping your boots dry.

After gaining a couple of hundred feet, the trail rounds a bed and enters the deep and dark canyon. Soon enter the Colonel Bob Wilderness. Under an emerald canopy of stately hemlocks and firs with frothing Fletcher Creek crashing in the distance, continue climbing. Waves of sword ferns appear to roll down the vertical canyon walls.

After about 1 mile the way gets rougher, growing rockier and rootier. Finally, the trail approaches the creek. Enter a magical spot where big mossy boulders corral the feisty waters. Stare across to the sheer vertical wall at the far side of the canyon, where you can also see the scars of avalanches and rockslides.

With good tread now a memory, the trail darts over slick rocks and skirts along damp ledges on a somewhat steep course. At 2 miles, after a slight descent, break out into a small clearing alongside Fletcher Creek. A huge cedar log acts as a bridge over the gurgling waters, and another pretty waterfall can be seen just upstream. This is a good spot to call it quits. Beyond, the trail peters out into a tangle of brush. Sit by the creek and enjoy a corner of the rain forest were few bootprints have been left behind.

|

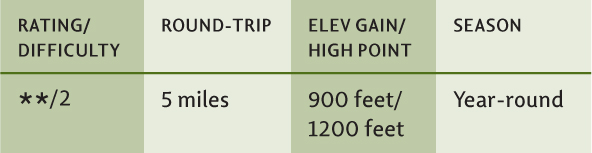

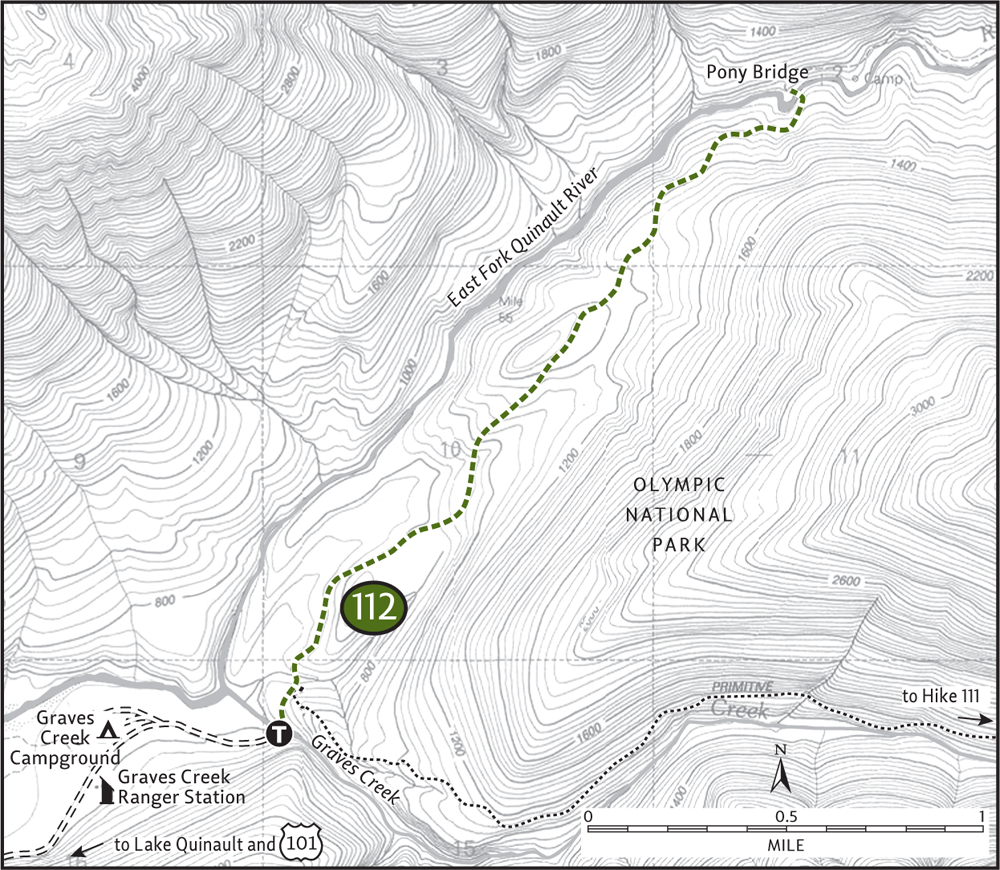

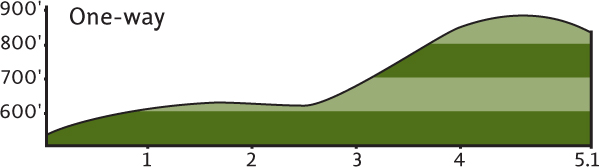

Graves Creek |

Winter hiking in the Graves Creek valley

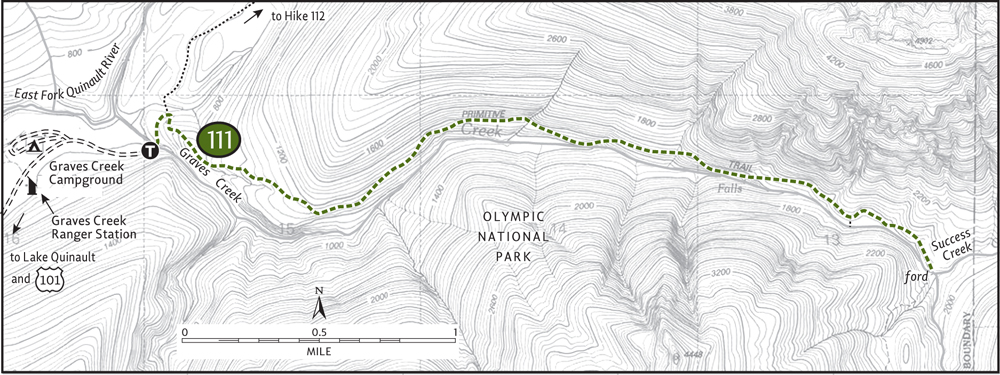

Maps: Green Trails Mt Christie No. 166, Custom Correct Enchanted Valley–Skokomish; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. Road from Quinault River Bridge is subject to temporary closures during winter; GPS: N 47 34.370, W 123 34.191

Perhaps the loneliest of the Quinault rainforest valleys, Graves Creek promises solitude among a multitude of ancient trees. And while chances are slim of running into other wayward souls, a chance encounter with an elk is possible. Through a deep canyon, Graves Creek booms and crashes on its way to the Quinault River, at times disappearing into a tight chasm. But the valley is never free from its thundering outbursts and explosives rants.

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam travel north on US 101 for 35 miles. Turn right (east) onto the South Shore Road, located 1 mile south of Amanda Park. Proceed on this road for 13.5 miles (passing the Forest Service’s Quinault Ranger Station at 2 miles), coming to a junction at the Quinault River Bridge. Continue right, proceeding 6.2 miles to the road’s end and the trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

Start this hike on the popular Quinault River Trail to Pony Bridge (Hike 112) and Enchanted Valley. Immediately cross Graves Creek on a sturdy bridge high above the churning waterway. In 0.25 mile come to a junction. Turn right onto the Graves Creek Trail, trading a well-worn pathway for narrow tread adorned with encroaching mosses.

Through a jungle of big trees draped in mosses and flanked with ferns, begin climbing out of the Quinault Valley. Numerous creeks flow across and, during heavy rain periods, down the trail. At 0.75 mile and after 400 feet of climbing, reach a bench high above Graves Creek. With caution, locate the waterway below as it tumbles through one of several box canyons lying along its route.

As you climb gradually, the valley walls grow steeper and Graves Creek’s thundering roar intensifies. In late spring numerous cascades fall from the surrounding slopes, adding to the commotion. As you continue deeper into the valley, the trail dips close to the wild waterway at a few spots. Then it’s more cascades, more rumbling, more climbing above the forbidding passages.

At 2.5 miles cross the first of two large avalanche chutes. Despite the low elevation (1700 feet) snow often lingers late into the spring. At 3 miles find a steep side trail heading down to a secluded pool on the creek. The main trail continues through big timber, traverses an open flat, and then at 3.5 miles descends to Success Creek. Here at the confluence of Success and Graves Creeks, two fords must be made if you wish to continue. Day hikers will want to call it quits here. Find a nice rock, pull out your lunch, and watch the dippers look for theirs.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Strong hikers may want to continue all the way to Lake Sundown, 4.4 miles and 2000 vertical feet farther. Consider car-camping at the Graves Creek Campground, a mere 0.3 mile from the trailhead. From the campground, enjoy a nice 1-mile loop trail through lush river bottomland.

|

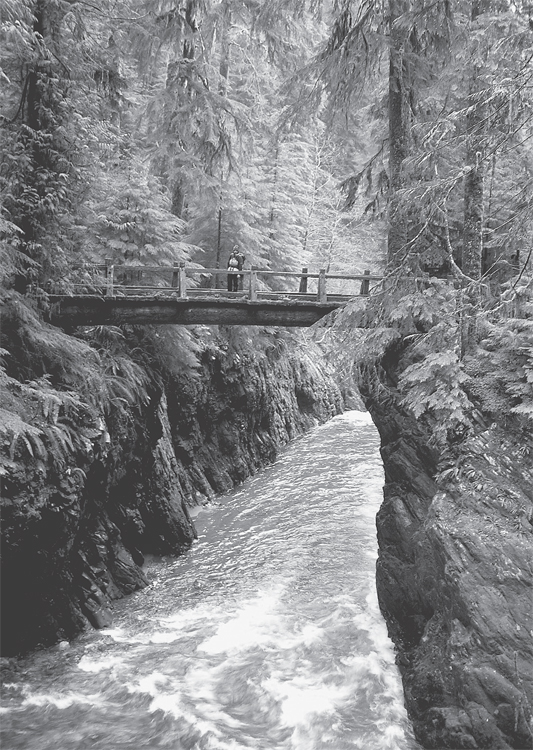

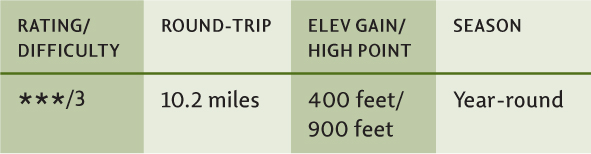

Quinault River-Pony Bridge |

Maps: Green Trails Mt Christie No. 166, Custom Correct Enchanted Valley–Skokomish; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. Road from Quinault River Bridge is subject to temporary closures during winter; GPS: N 47 34.370, W 123 34.191

|

Big trees, a narrow canyon, and a little taste of the Enchanted Valley Trail, a 19-mile path deep into the Olympic interior. Explore the same primeval rainforest valley that explorers of the 1890 O’Neil Expedition set out across. Witness a wilderness not unlike the one those intrepid souls experienced. Come here in the heart of winter and find yourself among one of the largest elk herds in America. |

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam travel north on US 101 for 35 miles. Turn right (east) onto the South Shore Road, located 1 mile south of Amanda Park. Proceed on this road for 13.5 miles (passing the Forest Service’s Quinault Ranger Station at 2 miles), coming to a junction at the Quinault River Bridge. Continue right, proceeding 6.2 miles to the road’s end and the trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

The Quinault is one of the grandest of the rainforest rivers. Draining much of the Olympics’ southwest corner, the Quinault is comprised of two main branches: the North and East Forks. This hike takes you along a portion of the East Fork, through a deep glacially carved valley.

Start by crossing Graves Creek on a large log bridge. In 0.2 mile come to a well-signed junction. Continue left on a wide and well-graded trail, an old road that once extended almost to Pony Bridge. Along a bench, away from the river, traverse moisture-dripping groves of towering hemlock, spruce, and fir. In winter scads of hoofprints mar the surrounding saturated ground. Stay alert for elk. The trail meanders a little over a small rise. Scores of creeks and rivulets run under, over, and sometimes down the trail.

At 2 miles the old road ends. Pass an old picnic table rapidly losing a fight with the elements; then begin to drop a couple of hundred feet to the river. Finally, at 2.3 miles, the East Fork Quinault comes into view. Through a fern-ringed narrow canyon of slate and sandstone, the crystal-clear waters bubble and churn. Walk a little ways to Pony Bridge, which spans this scenic gorge. Enjoy an unobstructed view of emerald pools swirling below and horsetail falls streaking the canyon walls. If you’ve trekked this way on a rare sunny day, retreat a few hundred feet on the trail to find a rough path leading down to some lunch rocks along the river.

Pony Bridge in the Quinault Valley

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Want to see more of the East Fork valley? Continue up the Enchanted Valley Trail on an up-and-down course along the river. Fire Creek, 1 mile farther, makes a good destination.

|

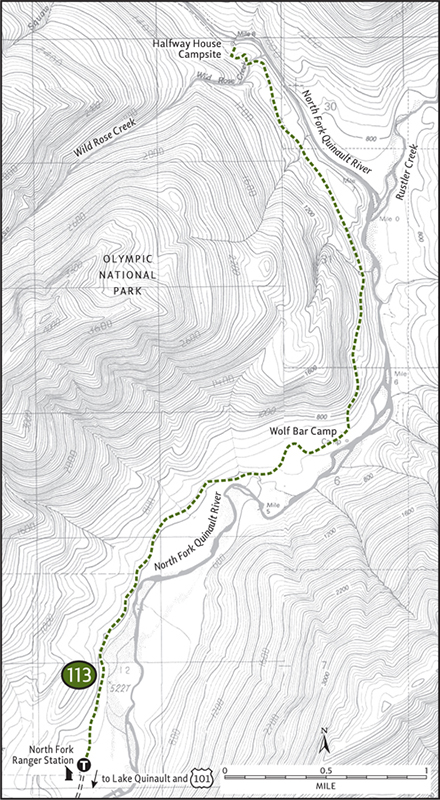

North Fork Quinault River-Halfway House |

Maps: Green Trails Mt Christie No. 166, Custom Correct Quinault–Colonel Bob; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. North Shore Road is subject to temporary closures during winter; GPS: N 47 34.542, W 123 38.889

|

Hike along a wild river sporting big bends and wide gravel bars that’ll have you thinking you’re in Alaska. Massive Sitka spruce, gargantuan western hemlocks, and corridors of mossy maples and speckled alders grace the way. Retrace part of the Press Expedition’s 1889–90 route across the Olympics, and visit the former site of a lodge that provided warmth and hospitality to trekkers during the 1920s and ’30s. Along the North Fork Quinault River, you can embrace the pure wildness and raw beauty of the Olympic rain forest. |

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam travel north on US 101 for 35 miles. Turn right (east) onto the South Shore Road, located 1 mile south of Amanda Park. Proceed on this road for 13.5 miles (passing the Forest Service’s Quinault Ranger Station at 2 miles), coming to a junction at the Quinault River Bridge. Turn left and cross the bridge. Then immediately turn right onto the North Shore Road, proceeding 3.5 miles to the road’s end at the ranger station and trailhead. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

Like many trails following rivers deep into the Olympic interior, the first couple miles of the North Fork Quinault River Trail were once a road. Building roads up these narrow, wet valleys was difficult enough, but maintaining them proved to be even more challenging. Winter storms and spring floods have a way of wreaking havoc on them. Over the decades and faced with limited budgets, the Park Service allowed some of these disaster-prone roadbeds to be converted to trail—a plus for wilderness and solitude seekers, but a minus for hikers seeking easier access into the backcountry. The decision to convert, not always met with approval, occasionally induces rifts within the hiking community (see “All Washed Up” in the Dosewallips River Valley section).

Lush rain forest in the North Fork of the Quinault Valley

The North Fork Quinault’s first 2.6 miles were converted long ago, making for an easy and enjoyable hike to a wide riverbank camping and picnicking spot known as Wolf Bar. Much of the way is right along the roaring river. And as in the past, the river continues to jump its bank, forcing reroutes and new tread to be built.

About 1 mile from the trailhead the first of several side creeks is crossed. While easy during summer, winter rains can make this and the other crossings difficult. At 1.5 miles traverse a huge gravel outwash area arranged with boughs of sword ferns and columns of maples swathed in moss. Next, cross a channel bed that may or may not be flowing. Traverse an alluvial island; then negotiate the channel once more. Now travel over more outwash, through groves of towering old growth and along newly exposed riverbanks.

At 2.6 miles arrive at Wolf Bar, a suitable destination for a shorter hike. Head out on the broad gravel bar for views of the surrounding steep-sided ridges adorned in swirling clouds. When the rain is in remission, worship the sun from this extensive outwash.

Beyond Wolf Bar the trail climbs a terrace, pulling away from the river. On an up-and-down course through thick forest, but always within earshot of the North Fork, the trail winds up the deep valley. At 5 miles, come to Wild Rose Creek, requiring a ford that may be dangerous during high water. The Halfway House site lies just beyond. Now a backcountry campsite, nothing remains of the old lodge. But the area’s charm is still in full swing. Find a piece of ledge to sit on to watch the swirling, gurgling river negotiate a narrow chasm.

|

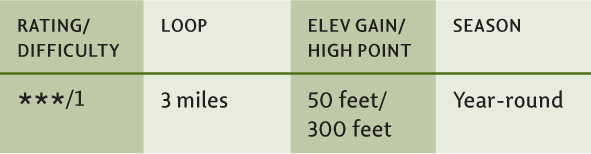

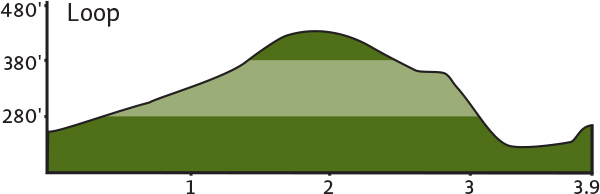

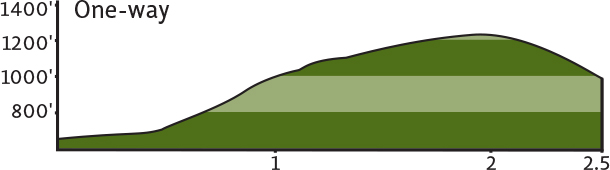

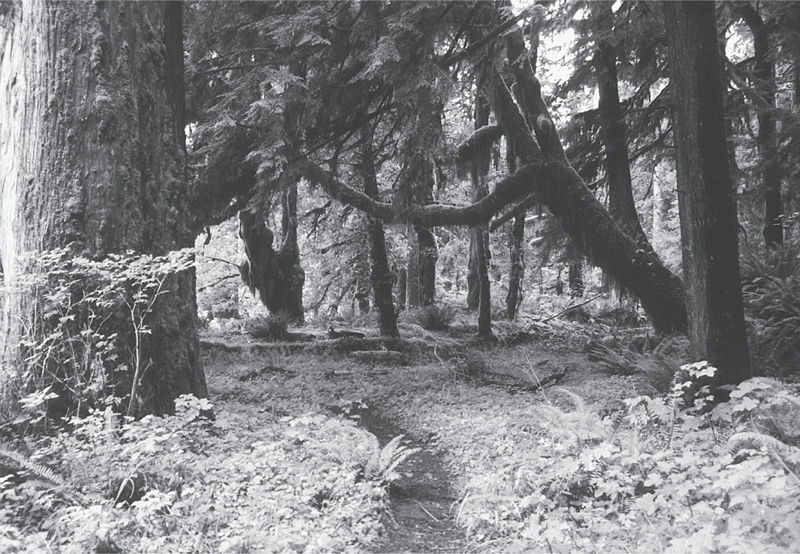

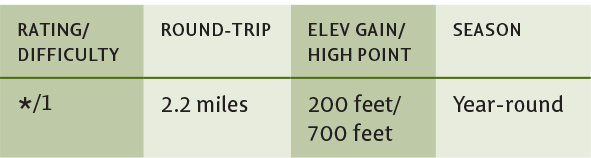

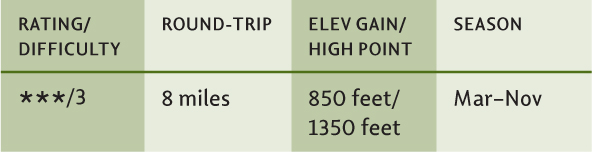

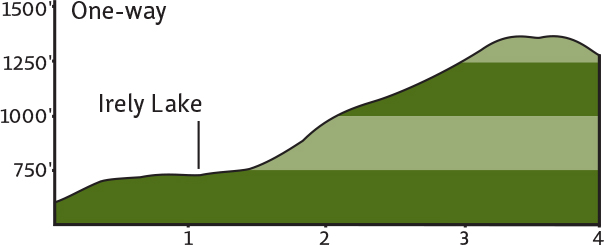

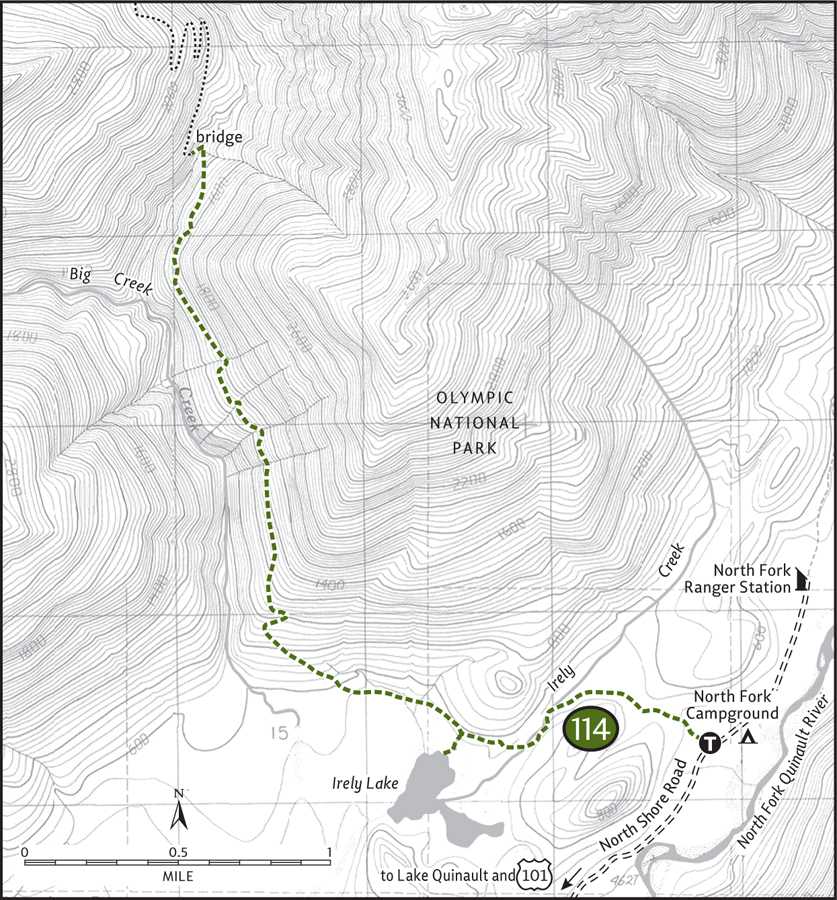

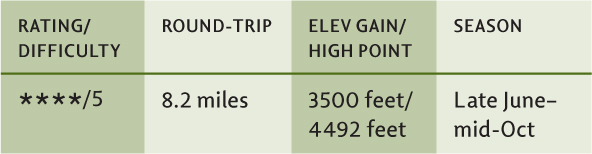

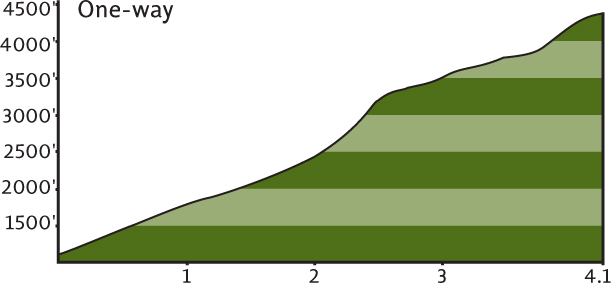

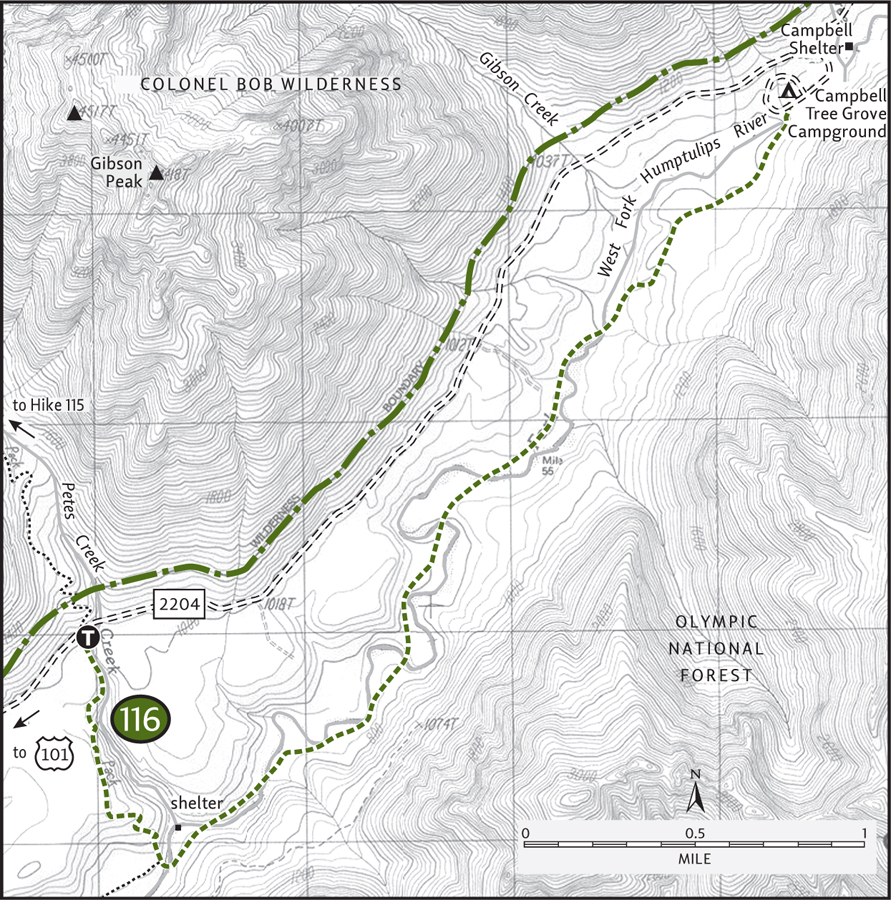

Irely Lake and Big Creek |

Irely Lake

Big Creek

Maps: Green Trails Mt Christie No. 166, Custom Correct Quinault–Colonel Bob; Contact: Olympic National Park, Wilderness Information Center, (360) 565-3100, www.nps.gov/olym; Notes: Dogs prohibited. North Shore Road is subject to temporary closures during winter; GPS: N 47 34.049, W 123 39.317

|

A leisurely, kid-friendly jaunt to a quiet body of water teeming with wildlife, or a more moderate push through ancient forest along a crashing waterway—it’s your choice. The forests of Big Creek, like those throughout the Quinault Valley, are impressive. Over 140 inches of rain fall here each year, saturating the forest floor and supporting massive cedars, lofty firs, hovering hemlocks, and clumps of shoulder-high ferns. Elk are abundant in this verdant valley, while hikers remain scarce. |

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam travel north on US 101 for 35 miles. Turn right (east) onto the South Shore Road, located 1 mile south of Amanda Park. Proceed on this road for 13.5 miles (passing the Forest Service’s Quinault Ranger Station at 2 miles), coming to a junction at the Quinault River Bridge. Turn left and cross the bridge. Then immediately turn right onto the North Shore Road, proceeding 2.9 miles to a parking area located on your right. The trail begins on left side of the road.

ON THE TRAIL

Irely Lake: Begin under a lofty canopy, compliments of a support team of colossal cedars and spruce. After a small climb of 100 feet come to a flat that’s bisected by Irely Creek. Turn south, following the skunk-cabbage-laced creek. Be careful on the rotten puncheon (planking that has deteriorated due to constant saturation). Beavers are active along this stretch, their handiwork causing occasional inundation of the trail.

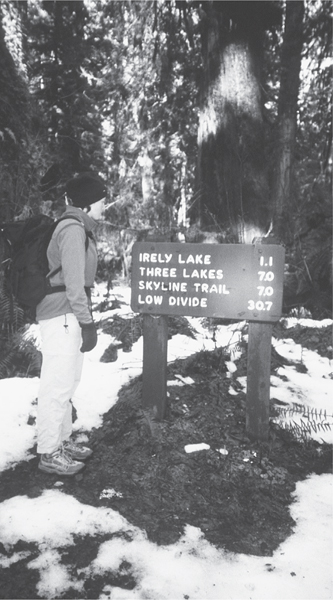

Starting a winter hike to Irely Lake

Cross the small creek on a log bridge; then head for higher and drier ground. At 1 mile reach a side trail that leads 0.1 mile down to a grassy spot on Irely Lake. The lake, more a big marsh, is a good place to sit still (if mosquitoes aren’t present) and scope out birds. Ducks, woodpeckers, blackbirds, and songbirds are present in large numbers.

Big Creek: Beyond Irely Lake the trail traverses muddy lowlands, crossing several creeks that often flood during periods of high rain (which is often). The tread gets rougher and rockier, heading deeper into the saturated, verdant forest. If you could overdose on chlorophyll exposure, it would happen here.

Cross a maple flat frequented by elk before beginning a steep climb high above Big Creek. The cedars are enormous along these steep slopes. Several behemoths lay toppled across the trail, victims of strong winter storms. Wind is the number-one agent of succession in the rain forests of the Olympic Peninsula. Strong gusts ensure openings in the canopy, allowing new growth to compete with the entrenched elders.

At about 2.5 miles traverse a massive mudslide from the winter of 2006. Slain giants lie jumbled in a mélange of rocks and earth. Continue skirting steep slopes, and then at 4 miles abruptly drop toward the crashing creek. With a small cascade on your right, work your way down a short rocky ledge to the sturdy bridge that spans the thundering North Fork Big Creek. It’s an impressive sight of hydrological force. Break out the granola bars and enjoy the show.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

You can continue on the Big Creek Trail, but the way gets steeper and rougher. Two miles farther and 1000 feet higher beyond the bridge is the world’s largest yellow cedar. Another mile and another 1000 feet of elevation gain delivers you to the Three Little Lakes and the beginning of the Skyline Trail, one of the premier backpacking routes in the park.

|

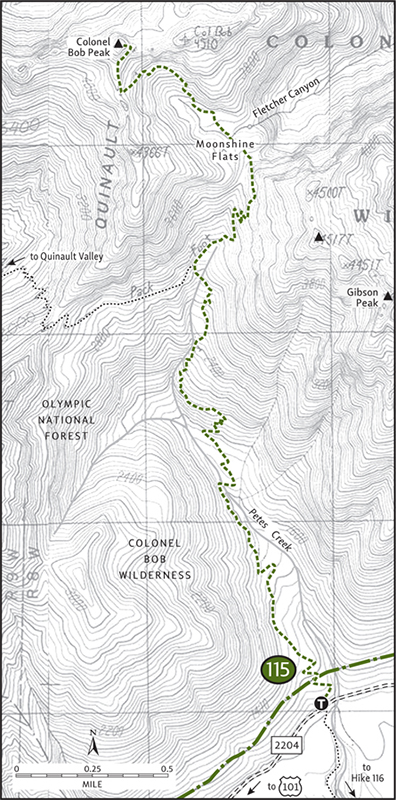

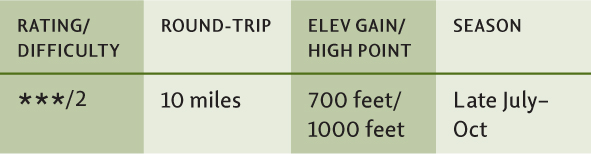

Petes Creek-Colonel Bob Peak |

Maps: Green Trails Grisdale No. 198, Custom Correct Quinault–Colonel Bob; Contact: Olympic National Forest, Pacific Ranger Station, Quinault, (360) 288-2525, www.fs.fed.us/r6/olympic; Notes: Northwest Forest Pass required; GPS: N 47 27.433, W 123 43.905

Climb a prominent peak on the western edge of the Olympic Mountains. From this 4000-plus-foot aerie above the saturated Quinault Valley, stare down upon sprawling rain forest. Enjoy an unobstructed view of shimmering Lake Quinault too, and from Mount Olympus to the Pacific take in an ocean of peaks and peek at the ocean. It’s a tough climb to this rugged outpost on the periphery of the Olympics, but the panorama it provides is a worthy pursuit.

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam travel 25 miles north on US 101. Just past milepost 112 turn right onto Donkey Creek Road (Forest Road 22, signed for Wynoochee Lake). Follow this paved road for 8 miles to a junction. Turn left onto FR 2204 and continue 11 miles (the pavement ends in 3 miles) to the trailhead at Petes Creek. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

The hike to this peak is just like the man it was named for: straightforward and to the point. Colonel Robert G. Ingersoll was a Civil War veteran, politician, orator, and free thinker who never stepped foot on this peak, but some admiring climbers who did thought the peak should be named for him. The good colonel eventually got a wilderness area named after him too, the only wilderness on the west side of the Olympic National Forest.

It’s just over 4 miles to the summit, but it’ll feel a lot longer. Most of the way is steep, with several rocky sections. Is it worth it? Absolutely! Colonel Bob offers views into country rarely seen from high above. It’s one of the very few hiker-accessible summits in the western reaches of the Olympics.

Start your journey on the Petes Creek Trail, immediately entering ancient forest and the Colonel Bob Wilderness. In just under a mile cross the creek. You may get your feet wet, you may not; some years the creek runs underground. The climb stiffens as the trail works its way up the west slope of neighboring Gibson Peak.

Heather enjoying lunch on the summit of Colonel Bob Peak—Lake Quinault in the background

At 1.5 miles traverse a brushy avalanche slope. Another larger slope is encountered soon afterward and views open up of the Humptulips Valley. Steeply zigzag through rugged terrain and at 2.4 miles come to a junction with the Colonel Bob Trail (elev. 3000 ft). Head right, climbing yet more steep brush-choked slopes and finally receiving a reprieve at a gap (elev. 3700 ft) above Fletcher Canyon (Hike 110).

The trail now heads northwest, dropping a bit to a tarn—boulder- and creek-graced Moonshine Flats. One mile and 1000 feet of elevation gain still need to be covered. Through subalpine forest and skirting basalt cliffs, the rough trail steeply switchbacks to the summit cone, the final 100 feet on steps blasted into the rock.

One look from this former fire lookout site quickly validates all your pain and suffering. Lake Quinault twinkles below. Mount Olympus glistens to the north, while Mount Rainier hovers in the east over rows of scrappy hills and ridges. And fanning out below from your aerie hub is an emerald network of luxuriant rainforest valleys—a burgeoning kingdom of biomass.

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

Colonel Bob can also be hiked from the Quinault Valley, but it’s a long trek (7.2 miles one-way) gaining over 4200 feet of elevation. However, the first 4 miles along Ziegler Creek to the Mulkey Shelter are through beautiful old-growth forest. The trail is good, rises just 1900 feet, and makes for excellent year-round kid- and dog-friendly hiking.

|

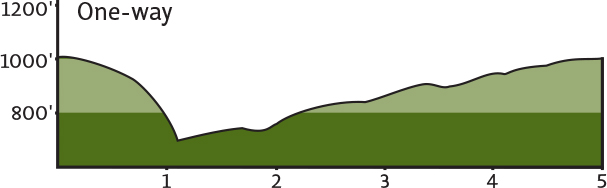

West Fork Humptulips River |

Maps: Green Trails Grisdale No. 198, Custom Correct Quinault–Colonel Bob; Contact: Olympic National Forest, Pacific Ranger Station, Quinault, (360) 288-2525, www.fs.fed.us/r6/olympic; Notes: Northwest Forest Pass required. River fords required, only safe during low flows; GPS: N 47 27.433, W 123 43.905

|

With spectacular groves of old-growth forest, meadows teeming with wildlife, and views of rugged surrounding peaks, the West Fork Humptulips River bottom is one of the most varied of the rainforest valleys. Devoid of visitors and traversing the edge of one of the largest roadless areas in the Olympic National Forest, this hike offers a true wilderness experience. The river must be forded eight times, but if amphibious adventuring is not for you, 1.5 miles of dry trail (and kid-friendly hiking) can be enjoyed year-round from the northern terminus of this hike at the Campbell Tree Grove. |

GETTING THERE

From Hoquiam travel 25 miles north on US 101. Just past milepost 112 turn right onto Donkey Creek Road (Forest Road 22, signed for Wynoochee Lake). Follow this paved road for 8 miles to a junction. Turn left onto FR 2204 and continue 11 miles (the pavement ends in 3 miles) to the trailhead at Petes Creek. Privy available.

ON THE TRAIL

Because this hike involves eight river fords within a 2.5-mile stretch, consider wearing a pair of old running shoes so you can keep plodding without having to continuously stop to lace up your boots. The terrain and tread between the crossings is generally level, a little brushy in spots, but not rocky or rough. It’s a great hike on a late summer’s day. The river warms up nicely, assuring no red feet along the way.

Start by heading 1 mile down the Lower Petes Creek Trail on a wide and gentle path, first through a grove of old cedars and hemlocks and then along an old clear-cut. With the sound of the West Fork Humptulips amplifying, the trail leaves the level terrace, dropping steeply 300 feet to meet the West Fork Humptulips River Trail on the lush river bottom. Head left a short distance, encountering the river and your first ford. Scan the wide gravel bank looking for a shallow and gently flowing crossing.

Once across, a grassy meadow graced with big maples lures you to continue. An old cedar-shingled shelter sits snuggly in the quiet grove. The trail wastes no time fording the river again. With the soothing song of the river constantly in range, head up the remote valley surrounded by rugged peaks of the Colonel Bob Wilderness to the west and Stovepipe and Moonlight Dome to the east. The trail traverses the western edge of the 6000-acre Moonlight Dome Roadless Area, one of the last large tracts of unlogged, unprotected national forest land in the rainforest valleys. Wilderness designation would suit this primeval piece of public property just perfectly.

Through groves of massive spruce and firs, across grassy openings, and through gently flowing ripples, wander up this de facto wilderness valley. At 3.5 miles complete your last ford. Now enjoy 1.5 miles of dry-foot trekking on excellent tread. At 5 miles, reach the river once again: A bridge here was swept away by flooding in 2007. However, an old growth giant has conveniently fallen across the river, providing a temporary span. Use caution and cross the river on it to the Campbell Tree Grove, one of the loveliest stands of old growth in the Olympics. Rest up and enjoy the return wade!

The West Fork of the Humptulips from the first ford

EXTENDING YOUR TRIP

The trail continues beyond the Campbell Tree Grove for nearly 5 miles. But the 7-mile stretch south of Petes Creek makes for easier and more interesting walking. The Campbell Tree Grove is a quiet and inviting place to set up a base camp for exploring area trails.

MEET THE ROOSEVELTS

The fact that nearly 1 million acres of wild land is protected on the Olympic Peninsula as a national park is primarily the work of two presidents: one a Republican, one a Democrat, both Roosevelts.

Lieutenant O’Neil was one of the first people calling for protection of the area as a national park back in 1890 after his second scientific and exploratory journey. In 1897 President Grover Cleveland created the Olympic Forest Preserve, but it lacked strong protection. An avid sportsman, President Theodore Roosevelt used the Antiquities Act of 1906 (which he signed into law) to proclaim 600,000 acres as Mount Olympus National Monument, primarily to protect the dwindling elk herds from unregulated hunting. Today the elk bear his name and number over 5000.

National monuments, however, don’t enjoy the same protections as national parks; timber, mining, and development interests began putting pressure on the government to open up the area to exploitation. In 1937 President Franklin D. Roosevelt visited the area, staying at the Lake Crescent and Lake Quinault Lodges and prompting him to declare, “This must be a national park!”

In 1938, four weeks before O’Neil’s death, FDR signed a bill designating 898,000 acres as Olympic National Park. Most of the coastal strip was added to the park in 1953 with a stroke from President Truman’s pen (a Democrat). In 1988 Republican president Ronald Reagan signed a bill declaring nearly 95 percent of the park as wilderness, the strongest protection afforded by law.

But work on the park isn’t complete. Conservationists and park officials have expressed an interest in further expanding the park’s boundaries. Hopefully, Congress and the president, both Democrats and Republicans, will agree and follow their predecessors’ enlightened examples.