![]()

The First Tick

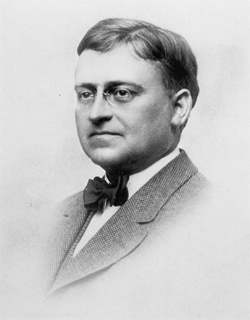

On the evening of March 30, 1922, the rain dropped a blanket of cold over the Mahoning Valley as James Ward Packard and his wife, Elizabeth, welcomed her father, Judge Thomas I. Gillmer, and a guest, Dr. John S. Kingsley, into their home, a handsome red-brick Colonial Revival on Park Avenue in Warren, Ohio, not far from the Victorian grandeur of the downtown courthouse. Outside, the streetlamps cast refracted halos of light onto the damp air. Inside, Ward, as he was known, dressed as he usually did, meticulously. Barely five-feet-four, he wore one of his custom-made wool suits, a waistcoat, and a bow tie. His slight physical stature notwithstanding, nobody stood taller in this town than the man whose decoratively embossed letterhead read “J. W. Packard.”

Eight months shy of fifty-nine, Ward had a full head of hair carefully combed into a three-quarter side part and greased back with tonic. He wore round, wire-frame spectacles on the bridge of his nose, and on his pinky finger an ornately engraved, eighteen-carat gold ring. Measuring about one inch long and half an inch wide, the ring was actually a small rectangular case. It framed a hexagon-shaped crystal that revealed an even smaller white enamel dial with black Arabic numerals and a minuscule winding stem crowning the top. Five years earlier, Patek Philippe had made this tiny mechanical watch, with the movement no. 174659, expressly for Ward, undoubtedly one of the benefits of his long-standing patronage of the Swiss watchmaker.

A handsome ebony walking stick stood against the wall in the foyer, another example of Ward’s enduring, unique relationship with Patek Philippe. In good weather, Ward went for brisk walks several times a week, usually following a path along the railroad tracks that fanned out northwest from Warren in the direction of Leavittsburg or southwest toward Newton Falls. During these regular jaunts he carried in his breast pocket a slim, worn blood-red leather Excelsior diary; there he recorded the weather, the distance, and the time it took to walk from one point to another. Without fail, he also carried one of his walking sticks in one hand and a watch in his pocket.

James Ward Packard. Courtesy of Special Collections, Lehigh University.

When possible, Elizabeth joined her husband. Sharing long strolls together had been one of the ways that, twenty-one years earlier, Ward had courted the woman who had strenuously vowed never to marry. A Vassar graduate, Elizabeth had studied medicine at Northwestern Women’s Medical College in Chicago, read law in her father’s chambers, and taught public school for two years in Arizona. She stood at least a head taller than Ward and was every inch his intellectual equal. The times and her prominent family defined marriage as a woman’s place in society, but Elizabeth found the idea execrable.

During the couple’s courtship, however, Ward slowly won her over. They found comfort in shared silence and the opportunity to discuss a spectrum of ideas. Fittingly, the pair had first met over books at Warren’s library, where her father was president of the Warren Library Association. Ward often brought Elizabeth science books; once he gave her a barometer. They were both gracious but not without tempers. Neither was given to trifles or open displays of emotion. Much to her surprise, they developed a deep bond based on intellectual kinship and caring. Following one of their walks, Elizabeth wrote in her diary, “Ward & I were very prosaic and dull. We never let that worry us however, that is one of the charms of our camaraderie, we take each other just as we happen to be and never make any effort to entertain one another. That is real friendship.”

The interplay of wit, substance, and banality had its desired effects. Three years after writing in her diary, “If I ever marry—but there’s no use of discussing that for I never shall,” Elizabeth relented. The pair became husband and wife in a hastily arranged wedding that came together on the morning of August 31, 1904, at her parents’ Italianate mansion on Mahoning Avenue. The bride wore an embroidered blue going-away gown and plumed hat. She was thirty-two, and Ward was not quite forty-one, both well past the blush of young love. Indeed the union came as such a shock that their wedding announcement read in part, “It was a complete surprise to many of their friends who are nonetheless quick to extend congratulations.” Not given to florid expressions, Ward noted the occasion in his diary as simply “Wedding.”

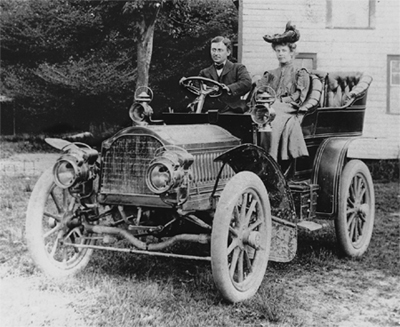

A photograph taken on the occasion shows the newlyweds in a Packard Model L touring car on the way to their honeymoon on the shores of Lake Chautauqua in Lakewood, New York. Stiffly pressed against the car’s high-backed tufted leather seats, with Ward at the wheel, the pair stared into their future, captured by the unknown photographer, still wearing their wedding finery and the faintest of smiles. Despite being married for twenty-four years, Elizabeth and Ward would remain childless.

Ward drives his bride, Elizabeth Gillmer Packard, to their honeymoon in his Packard Model L, August 1904. Courtesy of Betsy Solis.

As with nearly all of the objects in his possession, Ward owned multiple canes. During the summer of 1917, months after he received his ring-watch, he commissioned Patek Philippe to produce for him a special walking stick. It was two months after the United States formally entered World War I when he made the request, and the piece took more than a year to manufacture. On September 18, 1918, Ward took delivery of the beautiful polished ebony cane topped with a winding sterling silver watch as its handle. The enamel dial had black Roman numerals and was designed to twist off the cane and be replaced with a mushroom-shaped knob of ivory, depending on his mood. On Ward’s instructions, the movement, the internal mechanism of the watch, no. 174826, was engraved Made By Patek Philippe & Co., Geneva Switzerland for J. W. Packard 1918. Ward put his new, one-of-a-kind walking stick to use at once.

• • •

Though he considered himself a mechanical engineer, Ward had spent the previous three decades pioneering some of the country’s most important industries of the Industrial Revolution and, along with his older brother, William Doud Packard, created entire businesses around them. His prolific ventures made him both a mogul and a millionaire several times over. His first effort, the Packard Electric Company, had put Warren on the map. Established in 1890 as a producer of high-quality incandescent lightbulbs, the company eventually grew into one of the biggest manufacturers of automotive and electrical systems. Nonetheless it was the Packard Motor Car Company that magnified the Packard name across the globe.

In 1899 Ward designed his first horseless carriage, a single-cylinder, single-seat roadster with a tiller for steering. Twenty-three years later, the Packard reigned supreme as America’s premiere luxury car. Favored by royalty, industrialists, and movie stars, the Packard was renowned for its elegant lines and superb engineering. “Ask the man who owns one,” exclaimed the company’s famous tagline. Indeed, on March 4, 1921, Ohio-born Warren G. Harding rode to his inauguration in a shiny Packard Twin Six with its regal lined hood and brass-rimmed windshields, the first U.S. president to travel by motorcar to his swearing-in ceremony.

• • •

On this cold spring evening in 1922, as the Packards and their guests sat down for dinner, the fortunes of both Ward and the country seemed buoyant. Before the year was over Packard Motor would report record sales of $38 million (in today’s dollars, an amount equal to more than $518 million), and its directors would reward shareholders with a 100 percent dividend on the company’s common stock. America was ebullient. Having survived the deadly influenza epidemic of 1918 and World War I, the country roared into the 1920s. (Packard Motor served the country admirably. In the Allies’ air corps, the Liberty aircraft were powered by Packard eight-and twelve-cylinder engines, originally built for the Packard Twin Six.)

Exuberant jazz music wafted from radios and drifted on plumes of smoke out of nightclubs. Prohibition spawned illegal speakeasies. Women began dropping their social constraints while raising their hemlines, largely untroubled by the new libertine spirit or the scruples that preceded them. It was a time of mass production, massive wealth generation, and mass consumption. The era would later be recalled as the Jazz Age, the Age of Intolerance, and the Age of Wonderful Nonsense. Whatever the period was called, America was undeniably at the start of the modern age and Europe began to recede in its shadow. This was a time of new heights and numerous firsts.

For Ward, an inventor of prolific ability, there were still a few more firsts to pull out from under his crisp, cuff-linked sleeve.

• • •

The evening at home marked one of the small and occasional intellectual gatherings organized by Ward, who several years earlier had shifted his attention from the day-to-day operations of his companies to focus on a range of interests and new inventions. This architect of an industrial empire preferred the anonymity of a simpler existence, surrounded by what was most familiar. A voracious reader, he consumed numerous trade publications, scientific journals, and literature. With his lantern camera outfitted with a French Darlot lens, he had produced hundreds of glass slides from photographing scenes of Warren: his sisters riding bicycles in their long billowing skirts in the spring, the steamships navigating across Lake Erie in the summer, and hummocks of snow nearly obscuring Warren’s streets in the winter.

Ward and his wife donated generously to civic, scientific, and educational causes, including giving $100,000 to the city of Warren for a new library. Along with his elder brother, William, better known as Will, his longtime business partner with whom he was extremely close, Ward gifted 150 acres along the Mahoning River to build a public park. But his largesse aside, Ward was not simply Warren’s regal money pot.

Generally timid, Ward was nonetheless relentlessly inquisitive and enjoyed the company of like-minded individuals. An invitation to one of his salons was coveted albeit infrequent. These informal evenings featured intense brain fencing, where the inventor held forth as a kind of avuncular Socratic figure. For him, everything posed a question to be solved and every design could be improved upon. The evenings were much like Ward himself: judicious, precise, and with a strong emphasis on culture.

Ward and Elizabeth had purchased a two-acre tract of land east of downtown and were in the process of building a four-story, twenty-room estate on the bucolic stretch between Oak Knoll and Roselawn Avenues. Elizabeth was particularly eager to move because she found the house on Park too close to the town’s center and the noise insufferable as motorcars rumbled through the narrow streets, practically at her front door. Her discomfort was ironic considering her husband’s considerable contributions to the auto industry.

This grand house was made of imported Scottish brick, mahogany, marble, and oak; a foyer fourteen feet wide and forty-four feet long allowed for an impressive entry from both the front and back of the house, with porte cocheres on each side. An entire wing was designed just for the servants, and there was a separate five-car garage with chauffeur’s quarters and a European-style butler’s pantry. Nearly an acre of the property was set aside for Elizabeth’s gardens. A showpiece of cerebral elegance, the new mansion included a library on the first floor, stocked from floor to coffered ceiling with the couple’s many leather-bound volumes, first editions, histories, and novels, each stamped with the Packards’ personal bookplate.

They were not a couple given to unbridled displays of ostentation, but they did not reject the luxuries their wealth afforded them. The house’s archways were molded to resemble the distinctive “tombstone” curves of the front grille of a Packard. The doors were fitted with cut-glass knobs, and the wall panels were hand-painted and imported from Europe. Adjacent to the sunroom was a small plumbing closet for watering plants so that the maids need not traipse across the house with water pitchers. Elizabeth’s master suite had built-in fur and jewelry vaults. In an almost unheard-of luxury for an era filled with opulent distractions, plans for the marble bath called for built-in water jets.

It would be two years before the new Packard family pile was ready, but Ward, already the recipient of more than forty patents, busied himself coming up with every mechanical contrivance imaginable for the house’s interior. By the time the house was finished, Ward was said to have deployed at least one thousand gadgets, each designed to replace some kind of manual labor. There was a burglar alarm and a turnstile switch that controlled all of the lighting from any room; an electric power plant was housed in the basement. So well designed were these systems that both would function perfectly well into the next century. Ward devised an elevator hidden behind the main spiral staircase and a second, secret set of winding metal stairs. The latter was meant to spirit the shy inventor up from the parlor to his second-floor bedroom without attracting the attention of the friends and visitors of his far more sociable wife.

The couple also maintained a summer estate, a thirty-two-room neo-Georgian mansion in Lakewood, where Ward built a machine shop on the second floor of the three-car garage. His continued tinkering in the workshop led to versions of a gasoline-powered lawn mower and an electric recording machine, among dozens of other prototypes and patent applications. Long fascinated with ships and boating, he devised a number of motors for his own small fleet. The DNA of several of these designs later powered American-manufactured speedboats, including every patrol boat deployed during World War II. The basement in his elegant Lakewood mansion was designed to resemble a great ship’s cabin, with a nautical ladder that descended from the first floor and portholes for windows.

A visitor to Lakewood might find Ward dressed in full yachtsman regalia sailing his five-foot cruiser, his forty-eight-foot pleasure boat, or his electric launch on Lake Chautauqua. He would wear an old suit if he sailed one of his rowboats. A point of pride was his hydroplane, the first on the lake. He especially enjoyed flying it at sunset and never ceased to marvel at the odd sensation of seeing the sun dip as he ascended high enough to overtake the glowing orange ball and then watching it sink once again below the horizon line.

Ward and Elizabeth Packard’s summer estate and gardens in Lakewood, New York. Courtesy of Betsy Solis.

Shortly after his wedding, Ward began construction on the property, which cascaded all the way to the lake, where he kept a jetty and a boathouse. The couple spent the next eight years designing the property to their exacting specifications, which included constructing an eight-hole golf course, a log cabin for games, and Elizabeth’s extensive formal English gardens, with neat boxed edging and endless gravel pathways connecting pools and pergolas to her groves of hardwood trees and various cutting, vegetable, and perennial gardens. Several existing cottages on the land had to be moved to make way for the new mansion. The relocation process, which took place over five years starting in 1905, was so careful that each cottage was moved without packing up its contents. As one local later described the scene, “Not a dish was broken, or an artifact damaged.”

For Ward and Elizabeth, Lakewood was more than just an escape from the repressively gummy heat of Warren’s summers; the town had been a favored Packard family destination stretching back to his childhood. In 1873 his father and uncle had bought up twenty-five lakeside acres along with the Lakeview Hotel and built a number of ornate cottages, creating an alternative resort colony to Newport for the growing industrial fortunes sprouting out of Ohio. The family, known for their many good works, maintained a large Gothic-style villa where they spent the summer seasons as one of Lakewood’s leading and most beloved families. While just a boy Ward operated the family hotel’s steam-driven electric light plant and Will ran the telegraph office.

• • •

James Ward Packard was born under a shining star. The second son of Warren and Mary (née Doud) Packard’s five children, he came into the world just two weeks before President Abraham Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address, on November 3, 1863. A small boy with an outsized intellect, he grew up in a period of often turbulent change that offered unprecedented opportunities to bold speculators and inventive entrepreneurs. Trailblazing was something of a genetic trait.

The first Packard in America was an Englishman named Samuel Packard who sailed across the Atlantic on the Diligence in 1638, landing in Plymouth County, Massachusetts. Following the American Revolution the Packards pressed forward, settling in northeastern Ohio, an area known as the Connecticut Western Reserve, bordering Lake Erie on its north side and Pennsylvania on the east. Ward’s forebears produced doctors, judges, and a brigadier general who served during the Civil War. In 1825 his grandfather William Packard moved to Lordstown Township, where he became its first postmaster. Some twenty years later, restless and dreaming of striking it rich, William abandoned his wife and ten children (including Ward’s father, Warren) and headed to California for the gold rush. He never returned.

In 1846, during the Mexican-American War, eighteen-year-old Warren Packard crammed a rucksack with his few belongings and and traveled six miles north to the seat of Trumbull County to put down roots in a town that happened to share his name.

Mid-nineteenth-century Warren, Ohio, was a somnolent hamlet in a quilt of picturesque villages running along the Mahoning River. Ancient thick maples and elms shaded its quiet dirt roads. Horses pulled wooden carts and carriages, making soft, rhythmic thuds. Black bass filled the Mahoning and quail the surrounding woodland. The First Presbyterian Church’s 225-foot spire and tower bell was the town’s dominant landmark. It had been painstakingly carried to Warren by ox cart in 1832.

When the inventor’s father arrived, Warren had a population of sixteen hundred people, five churches, twenty stores, three newspapers, two flour mills, one bank, and one woolen factory. On Millionaire’s Row, which fanned out from the town’s center at Mahoning Avenue, Victorian, Gothic, and French Empire–style mansions stood like preening peacocks. Railroad tracks were being laid across the country at a furious rate, but it would be another forty years before the full-scale construction of railroads connected Warren to the rest of Ohio. Commerce and shipping were still conducted mainly by canal, lake, and river, extending from the Ohio River to Lake Erie, which kept Warren insulated for a time from the manufacturing and industrialization that had transformed the growing steel towns of Niles and Youngstown downstream. The town developed at a languid pace into a prosperous burg of merchants and refined culture. Warren’s blue skies would not be obscured by chimneys belching plumes of black smoke until the end of the century.

By the time Ward entered the picture, his father had become one of Warren’s most prominent businessmen and the Packards one of its leading families. Within four years of working for a local iron merchant, Warren Packard bought the business outright, along with a competing iron foundry that manufactured axles and hammered iron. The elder Packard earned a reputation as a man of “broad vision and optimistic views . . . able to carry out to magnificent completion plans others would not dare undertake.” In due course, he expanded his interests along with several partners into hardware stores and saw and lumber mills, spreading his businesses into Pennsylvania and New York. Eventually he was named a director of the Western Reserve Bank. Packard supplied the men who were building the railroads as the railroads were building a new America. He owned the largest iron and hardware business operating between Cleveland and Pittsburgh. It was said that his lumber business furnished half of the wood used to build the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad that stretched across the western tip of New York into Pennsylvania.

When Ward was a boy, the family lived in a modest brick rental house on East Market Street and Elm Road. As Warren’s fortunes improved the family moved into a larger house on fashionable Courthouse Park. Ward and Will had three sisters, Alaska (named in honor of the Alaska Purchase of 1867), Carlotta, and Cornelia Olive. By the time Cornelia was born, nearly fourteen years after Carlotta, the family had built a magnificent French Empire–style mansion on High Street at the top of Millionaire’s Row. The Packard mansion, with its gabled roof, carriage house, fourteen bedrooms, and ballroom, was the grandest ever built in nineteenth-century Trumbull County.

Life inside the Packard mansion was exuberantly cheerful among the silver sets and crystal chandeliers, but it was also disciplined and purposeful. Warren Packard impressed upon all of his children the importance of education, hard work, and culture. And he set the example for his family. For fifty-one years, until he died in 1897 at sixty-nine, Warren began the day at 5 o’clock and worked through the evening, stopping only at 9 o’clock.

Mary Packard had a softening influence on the family, and Ward was particularly close to her. A small, bright-eyed woman, she took delight in her menagerie of dogs and children. One family friend called Mrs. Packard a “jolly” woman who was kind and delightful, behaving more like a big sister to her children than a parent. A standing member of Warren’s aristocracy and a regular churchgoer, Mary was also politically active. Among the first women in Warren to join the Political Equality Club, she would attend local lectures given by the leading suffragist Harriet Upton, the first woman to serve on the Republican National Executive Committee.

In the fall of 1874, when Ward was eleven, his parents thought it time to expand the horizons of their intellectually curious but culturally narrow son and sent him to receive an education in refinement and worldliness on a six-month excursion across Europe, beginning in Southampton, England. He was accompanied by family friends from one of Warren’s oldest families, Dr. William and Laura Iddings, and a governess. In the course of his business dealings, Ward’s father himself had made several trips across the Atlantic, during which he set up a pipeline to import European hardware.

From the time he could write, Ward received a pocket-size leather Excelsior diary each year. While abroad, he catalogued in his measured boy’s hand thrice-weekly French and Italian lessons, visits to ancient ruins and cultural sites, and the weather. Mostly, however, he logged days of tedium and abject loneliness, noting whenever he had and had not received word from home. In the south of France on January 23, 1875, he wrote, “Weather was very hopeless the wind was blowing very hard and we did not do anything I received nothing.” With attention verging on the obsessive, he made sure to assess the amount of time and distance between destinations. “Left London at quarter of three and to Liverpool at quarter of eight, 201 miles,” he noted on March 16, 1875.

When tired of the art and ruins, he holed up reading David Copperfield or the latest copy of Youth’s Companion magazine that he waited eagerly for his sisters or mother to send to him. Mostly he calculated the miles and hours until he would at long last return to Warren. His fancy European education did leave one indelible impression: above all else, he learned that he just wanted to go home.

• • •

Ward’s universe was contained in Warren, a tight drum of little more than sixteen square miles, animated by Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, Nikolaus Otto’s four-cycle internal combustion engine, and A. A. Pope’s Columbia Hi-Wheeler. He didn’t need to venture far to expand his world from the comfort of his own bedroom.

Unlike most boys, Ward wasn’t given to exploring the muddy woodlands surrounding Warren. Obsessed with mechanical invention, he preferred tinkering to the exclusion of nearly all other pursuits. Every advanced device of the period—firearms, phonographs, cameras, steam engines, railroad engines, telegraphy, and bicycles—fascinated him. As his fellow students pored through detective novels attempting to puzzle together the clues, Ward developed his stock in trade: finding new ways to improve existing devices and machines and seeking to convert everyday actions into mechanical operations. Not yet twelve, he rigged up a contraption that allowed him to open and close his window without having to leave his bed.

He and Will, born exactly two years and two days apart, were inseparable. In sleepy Warren, where residents remained suspicious of innovation, wanting nothing of industry, Ward and Will became known as the brothers “who insisted on doing things and making things.”

Some 240 miles away in Dayton, another pair of brothers, Orville and Wilbur Wright, began exploring flight. After their father, Bishop Milton Wright, gave them a toy Penaud helicopter fashioned after a flying Chinese top, the two took up bicycle building, which soon led to flight machines. But the fledgling field of electricity most captured Ward’s and his brother’s imaginations. In the decades since the British chemist and inventor Sir Humphry Davy first demonstrated his arc lamp in 1809 by connecting two charcoal sticks to a 2,000-cell battery, a variety of electric arc lamps had been developed that created an electric current flow through an “arc” of vaporizing carbon. Since then, men all over the world sought to create a more durable and commercial version of electric illumination. Although still a boy, Ward was one of them.

One evening Ward persuaded his brother to help him concoct his own arc lamp. After the rest of the family had retired for the night, Ward and Will sawed the knob of their bedroom door in half and joined the two pieces to opposite poles of an induction coil. Their handiwork did not conduct electricity but filled their father with a mix of consternation and pride upon discovering their deed the following morning, when he came to rouse his sons from bed.

After a few weeks of intense effort, the brothers startled the gentle folks of Warren one evening with a huge arc lamp dangling out over the street in front of the Packard mansion that produced a blinding light. All of Warren emptied out of their houses and businesses to see one of the first electric lamps on a city street anywhere in the country.

• • •

As an adult, Ward was drawn to clocks and watches. It was precisely this interest that earned Dr. John Kingsley an invitation to the Packards’ home on that rainy March evening in 1922. Kingsley arrived from Salem, Massachusetts, bringing a group of unique historical watches from the Lee collection, housed at the Essex Institute, a literary, scientific, and historical society. Charles Mifflin Hammond, a prominent New Englander turned California vintner who was also the brother-in-law of Theodore Roosevelt, had originally owned the timepieces, which his widow donated to the institute in 1917. The collection represented numerous examples of timekeeping from around the world. In addition to pocket watches there were 152 clocks, including some with English cone-shaped, spiral-grooved fusee movements that used pulleys to equalize the irregular pull of the mainspring, often found in clocks made during the nineteenth century. Along with several curious instruments from China and Japan there was an unusual Dutch Friesland clock that displayed a view of a harbor just below the dial where several tin ships bobbed on undulating tin waves in sync with the clock’s movement. A timepiece made in 1750 by James Ferguson of London indicated the time of twelve different world cities simultaneously.

The Institute arranged to bring a selection of the watches to Ward for his viewing at home. His enthusiasm for mechanical perfection and a lifelong passion for timepieces had earned him a reputation that nearly matched his status as an auto magnate. Over the years, he had acquired a growing collection of significant watches, becoming one of the country’s most important connoisseurs.

As a boy, Ward tinkered with every clock in the family home, studying each intricate part until he understood how they worked together, like a three-dimensional game of chess. Reassembling them, he often improved their operation, a habit he did not abandon as an adult. Once, just days before Christmas, he took apart one of his in-laws’ Seth Thomas shelf clocks, a popular manufacturer whose clocks were rather simple instruments that used a wooden pendulum as a swinging weight for the timekeeping mechanism. Although widely employed since the seventeenth century, such devices were prone to inaccuracies if the clock did not remain virtually motionless. On a whim, Ward removed the wooden pendulum and replaced it with an electromechanical pendulum of his own design. The new apparatus used a coil wrapped around a metallic core that produced a magnetic field. When an electric current passed through it, it provided an impulse to the pendulum, which made its timekeeping more accurate. Like the master clockmakers of previous centuries, on the inside of the wooden clock frame Ward signed and dated his handiwork in his spidery pen, JW Packard Dec 18, 1904, and quietly placed it back on the shelf.

Following dinner Ward led Kingsley and Judge Gillmer down to the basement, dubbed “the gun room,” where he usually entertained his guests. The trio repaired to view the watches under the room’s brightly painted frieze that depicted various Packard models amid a colorful backdrop of landscapes. The images were taken straight from the motor company’s marketing calendars. Evidence of Ward’s particular tastes was everywhere. On the mantel rested a pair of original Packard automobile lamps and an automobile clock. Small electric motors, microscopes, and various mechanical calculators and typewriting machines filled every available surface. Ward owned a copy of each make and model of these machines. Rather haphazardly, a trumpet and a Victor phonograph sat on the window seat. An ancestral bear gun hung directly over the brick fireplace, and perpendicular to it a wall rack held four U.S. Army Springfields with fixed bayonets.

Ward collected firearms much as he did timepieces, for their mechanical workmanship. One of his guns was outfitted with a diamond sight, and he was said to own one of sharpshooter Annie Oakley’s pistols. A dozen years earlier he had commissioned the New York jeweler Tiffany & Co. to customize his .38 Smith & Wesson double-action perfected revolver. Tiffany engraved the gun’s black barrel, adding gold, diamond, and platinum inlays, while the beautiful ivory handle was carved with scenes from the Wild West and featured a cowboy on horseback. (On close inspection, the cowboy’s face looked rather similar to Ward’s own visage.)

If anything, Ward was an aesthete. In his view, a piece of perfectly executed machinery should not preclude it from also being a fine piece of art.

With watches from the Lee collection spread out before him, Ward picked up one of the smooth gold pieces and turned it over in his hand. Tugging gently at the chain in his pocket, he pulled out a small penknife that dangled from the fob and deftly slid the point of the tiny blade into the case’s hinge, springing it open like an oyster. The movement, the watch’s inner workings, piqued his interest. Exposed, the movement revealed a mechanical tradition extending well beyond the fifteenth century. With loupe to eye, Ward magnified the minute whirling balance wheels, toothed escape wheels that clicked as they turned, and scurrying ruby pallets. The movement offered order and function in its purest, most ingenious form. Every component had a purpose that in turn sparked an entire series of events. From the outside, a polished gold watchcase was a thing of obvious beauty, but to peer beneath the dials was to view a complex universe in microcosm.

Over a twenty-four-hour period, a fine instrument ticks some 432,000 times. Every part of the mechanism strikes 18,000 blows an hour, adding up to more than 150 million beats a year. Hundreds of tiny, handcrafted moving parts are needed. The pivots measure barely .0028 inch in diameter. By one estimate, the screws are so small that it would take 20,000 of them to fill a thimble. A horologist once described the adjustment process as so delicate, “a pencil mark on a scrap of paper would make a difference in the balance.” Hardly trifles, mechanical watches were constructed to last through the generations.

For an engineer dedicated to technical perfection, horology offered the ideal preoccupation. It is perhaps the only discipline where a 99 percent precision rate is considered a failure; the 1 percent variation translates into a woefully inaccurate fifteen minutes off each twenty-four-hour period. Alvan Macauley, the president of Packard Motor, would say of Ward, “Crudeness and imperfections hurt his sensibilities.” As Ward studied this Lilliputian world of screws and pivots, a new watch that he desired had already begun to take shape in his mind.

Long ago Ward had become infected with what is known in some circles as the horological virus. An obsessive fever that brought kings to their knees and lovers to ruin and turned mighty industrialists to putty, it began simply with ownership of one watch and led without reservation to the desire to own every variation and then to own something that nobody had ever held.

Watches were not just everyday objects. There was something supremely intimate about a pocket watch. Like most men of means at the time, Ward possessed more than one timepiece. They were functional, of course, but their stylish gold cases, some engraved or filigreed or enameled and set in pearls, indicated they were more than just utilitarian.

During his early collecting, Ward came to own at least eight antique and technically significant watches. An enviable inventory, they included a rare eighteen-carat gold Victor Kullberg chronometer with a minute repeater. Appointed chronometer maker to the king of Sweden in 1874, Kullberg was considered one of the most skilled horologists of the nineteenth century. On the movement of this watch were markings denoting its placing at the Paris World’s Fair timing competitions: 4 Diplomas of Honour, 10 Gold Medals Award Grand Prix, Paris 1900. Ward’s early acquisitions included a beautiful late eighteenth-century enamel by the Swiss watchmaker Guex à Paris and an eighteen-carat gold verge watch by Chevalier of Paris made in 1790. Verge escapements, with their toothed wheels and a balance staff, which locked and released the mechanism’s movement, had been used since the fourteenth century and were an important turning point in horology, marking the shift away from measuring time by continuous processes, such as the flow of water or the swing of pendulums, and toward the development of all-mechanical timepieces.

Since his early collecting years, however, Ward’s connoisseurship had evolved sharply. By the time he entertained Dr. Kingsley, he had moved away from solely decorative pieces and lovely antiques and gravitated toward unusual instruments with the highest technological skill and precision, in particular those that incorporated a number of complicated functions outside of routine timekeeping, such as perpetual calendars and phases of the moon, called grandes complications. More than simply acquiring these complicated instruments, Ward took an active hand in their design, instructing the great watchmakers to create pieces with some innovative feature or to integrate an unprecedented combination of complications.

The auto magnate was the type of patron with whom the finest watchmakers hoped to curry favor. He was cultured, passionate, and fabulously wealthy. But in his approach to collecting he looked to watchmakers to transform his inventive, most florid musings into a ticking mechanical ensemble that expanded engineering beyond its known boundaries.

In 1905 he took receipt of his first watch from Patek Philippe, with the movement no. 125009. The debut timepiece, a grande complication, was a fine eighteen-carat gold open-face chronograph, with a minute repeater, perpetual calendar, and grande and petite sonnerie striking full and quarter hours. Unknown to both Ward and the watchmaker at the time, the 1905 chronograph was the first shot in a contest that would span decades. While Ward came to favor a handful of watchmakers, including Vacheron Constantin, he had found a kindred spirit in Patek Philippe. In Ward, Patek Philippe discovered an exquisite patron with obsessive tastes, unsparing hubris, and limitless funds to underwrite his fancies.

Beyond technology, Ward’s influence extended to design, and each watch reflected his refined sense of style. Cases and rims were decorated with engravings and Art Nouveau motifs. The case backs sported his signature monogram in raised bas-relief in blue or black enamel or gold. It was a version of the same stylized emblem that he used on his own stationery.

Ward approached the creation of a new watch with the mind of an engineer and the heart of a lovesick suitor. He derived enormous pleasure from establishing some new engineering feat nearly as much as he relished discovering the answer. With each new watch commission he pursued an undiminished desire to marry superb craftsmanship with technological achievement. In doing so, he drove Patek Philippe to achieve ever greater heights of complexity and precision in ever greater combinations.

Six years earlier, Ward had received the first of what would be his two greatest grandes complications produced by Patek Philippe. An extraordinary eighteen-carat gold pocket watch possessed a total of sixteen complications. Ward took possession of the watch during the same year that the Packard Motor Car Company introduced its twelve-cylinder cars. The Packard Twin Six line established the company as the most popular American luxury car and was in fact called America’s Rolls Royce.

The très grande complication, given the movement no. 174129, was the most extraordinarily complex timepiece that Patek Philippe had created in its own storied history. In addition to the perpetual calendar with retrograde date and moon phases, the watch had power reserves both for striking and movement and a sixty-minute recorder, as well as grande and petite sonnerie on three gongs, which struck the number of hours on one gong and the quarter-hours on a second, all chiming in different tones. This particular complication had been invented before electricity so that its owner might distinguish the time without actually peering at its dial.

The stunning watch’s greatest technological achievement was its seconde foudroyante (lightning) chronometer. The chronometer measured time increments to the fraction of a second, dividing each second into five jump steps, each step indicating one-fifth of a second. At the press of a button the hand appeared to split into two, enabling the mechanism to time two separate events simultaneously, two individuals in one race, or even several successive stages of a single episode. Its manufacture sent a shock through the watchmaking world, eventually setting the stage for a horological high noon.

• • •

As the evening drew to a close Ward’s thoughts had already turned to his next timekeeping masterpiece. For some time, yet another grande complication had been taking shape in his mind, an epic pocket watch. The instrument would stretch all horological and aesthetic limits, leaping past the handful of timepieces that had taken their place in horological history. He wanted a watch that was geographically calibrated to Warren, Ohio, with the pièce de résistance a celestial chart that navigated the heavens exactly as he saw them outside his bedroom window. In timekeeping’s fabled history, only one other pocket watch in the modern era, the Leroy No. 1, finished in 1904 for a Portuguese coffee tycoon, featured a nocturnal map of the skies.2

Again Ward turned to Patek Philippe, who had never produced a sky chart. For this latest endeavor, Ward as usual insisted that no expense, effort, or daring be spared. For the watchmaker, with its considerable skill and imagination, this appeared to be the commission of a lifetime.

At this point, the number of watches in Ward’s collection was climbing toward the hundreds. Jules Jürgensens, Agassizes, Vacheron Constantins, and Walthams, in addition to numerous French and British pieces and perhaps more than two dozen custom-designed Patek Philippe timepieces—it was a collection of masterpieces. Obsessed, he was after a watch that contained the greatest number of complications in the boldest combinations in the smallest space imaginable.

And so in the year 1922, when the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gave women the right to vote, the British archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the ancient tomb of the Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings, and the American-born poet and playwright T. S. Eliot published The Waste Land, Ward changed horological history. This latest commission would become the most important grande complication in his considerable collection and one of the most seminal in the world of horology.

The eighteen-carat gold pocket watch, designated with the movement no. 198023, would require five years to complete and would come to be known simply as “the Packard,” one of the most celebrated timepieces in history. Knowledge of its existence would eventually reach the fabulously wealthy and immensely private collector Henry Graves, Jr., a man who made it his personal business to possess “the best of the best,” a man who was engaged in his own quest to possess a complicated masterpiece of historical proportions.

For Ward, the Packard was proof that the impossible was merely a problem waiting to be solved.