CHAPTER 3

As Ted walked around to the third point of the triangle, I was lost in my own reflections. How often I had fallen into the role of Persecutor. There were times I had insisted someone else was in the wrong; I just knew I had to be right. I had often blamed others for the way I felt or for the way things turned out. I didn’t like seeing myself as a shadowy Persecutor. It felt better thinking of myself as the innocent Victim.

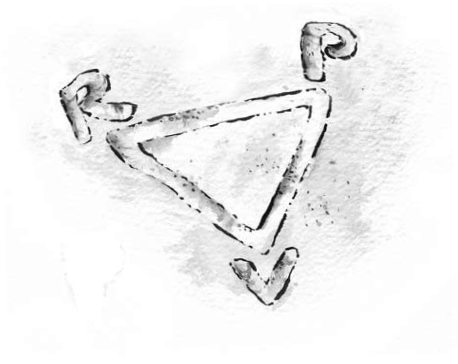

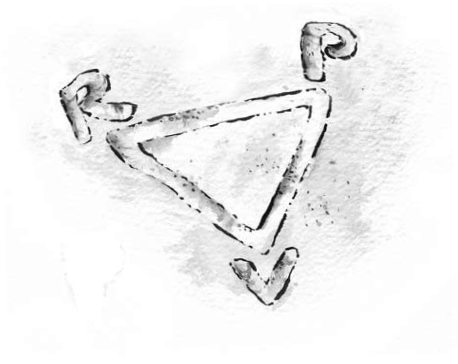

Ted reached out with the shell toward the upper left corner of the triangle and wrote an R.

The Rescuer

“This third role—the one who steps into the dance between Persecutor and Victim—is Rescuer. The dictionary defines the verb rescue this way: to free from confinement, danger, or evil; to save or deliver. The Rescuer may also try to alleviate or lessen the Victim’s fear and other negative feelings.

“Here, too, a Rescuer isn’t always a person. Addictions to alcohol or drugs, sexual addiction, workaholism—all the ways we numb out—can rescue the Victim from feeling his or her feelings.”

“I know how badly I want to escape from those feelings when I’m in despair,” I admitted. “Having one too many bottles of beer, playing just one more computer game, or zoning out with the sports channel might be Rescuers I’ve used to feel better.

“But it sounds like you’re making the Rescuer out to be a bad guy,” I added. “Isn’t the Rescuer supposed to be a hero, or at least a helper to the Victim?”

“It might seem that way on the surface,” Ted responded. “A person who steps into the role of Rescuer usually does so with a sincere intention to help. But think about it: what the Rescuer is doing—often unconsciously— reinforces the Victim’s Poor Me perspective, by saying or thinking, ‘Poor You.’ Same message, different point of view.”

Ted pointed to the roles with his walking stick as he spoke. “So you see, instead of helping or supporting the Victim, the Rescuer just increases the Victim’s sense of powerlessness. Unwittingly, the Rescuer enables the Victim to stay small, even though this may be the farthest thing from his stated intention. The Victim ends up feeling ashamed and guilty for needing to be rescued and becomes dependent on the Rescuer for a sense of safety.

“Rescuers look like good guys, but their helpful actions often cover up an underlying fear. Rescuers aren’t bad, either. But it is fear that motivates them to fly to the rescue.

“Persecutors fear loss of control. Rescuers fear loss of purpose. Rescuers need Victims—someone to protect or fix—to bolster their self-esteem. Rescuing gives them a false sense of superiority that covers their fear of being inadequate. Rescuers get to feel good about themselves, as long as they don’t admit that Victims could meet their own needs without them. With Victims to rescue, Rescuers feel justified; they avoid abandonment by being there for others. They foster dependency by becoming indispensable to a Victim’s sense of well-being.”

“But Ted, now you’re making the Rescuer sound like a Persecutor!” I objected.

“You’re on to something there,” he said. “It’s not unusual for a Victim to switch from seeing the Rescuer as a kind of savior to seeing her as a Persecutor who reminds the Victim of his dependency. In reality, the Rescuer avoids becoming a Victim herself—which is the same motive that drives the Persecutor’s behavior. The Rescuer, though, is avoiding abandonment and loss of purpose. The Rescuer often sets herself up for disappointment and rejection when a Victim won’t do as she advises or doesn’t appreciate her help. Then the Rescuer feels like a martyr: one more name for a Victim.”

Ted stood up straight and again motioned with his walking stick toward the Drama Triangle he had drawn in the sand.

Ted explained, “The Drama Triangle, made up of these three roles, shows up in many different cultures. It is maintained through stories, movies, and folktales. Many of the classic fairy tales perfectly depict the Drama Triangle. Consider the ancient example of the damsel in distress (Victim) who anxiously awaits her rescue from the villain (Persecutor) by the handsome prince (Rescuer), who is then supposed to protect her throughout a lifetime lived happily ever after.

“It may seem that the tale reaches a happy ending, but in reality the Drama Triangle’s pattern ultimately repeats itself. Eventually the prince/husband becomes domineering, and the damsel/wife becomes dependent or grows cold to her savior’s advances. The rest of the story—what happens after the illusion of a cheery ever after fades away—is where the Drama Triangle shows its true colors. This dreaded dynamic is all too common in human relationships.”

Shifting Roles

“The Drama Triangle is a tangled web,” Ted continued. “A person may play any one of these roles, or he may vacillate between them. The roles may be obvious and explicit, or subtle and seductive. The Persecutor can be a crying baby or a two-year-old throwing a tantrum at the grocery store. The Rescuer could be an extra glass of wine, or a friend saying, ‘That’s awful,’ as you complain about what’s been done to you.

“The three roles are intertwined. So when a person changes positions, the other people involved must shift their roles, as well.”

I saw how my former wife and I had taken turns as Victim and Persecutor. I thought of well-meaning friends who supported each of us as we complained about the other’s faults. I thought of a dear friend of mine, too, and I shared his story with Ted.

My friend had married a beautiful woman with two children. When they met, she had been struggling to make ends meet, and the children’s father was mostly absent from their lives. My friend was excited about his instant family and enthusiastically embraced his new role of primary provider and stepdad. He had unwittingly become a Rescuer.

As my friend worked to save his damsel from her distress, several years passed, and the children entered that often rocky road of adolescence. He and his wife argued about what it was reasonable to expect from their teenagers. My friend’s wife felt he was critical and judgmental of her parenting. But from his perspective, my friend was only offering helpful alternatives. He had maintained his role as Rescuer. What he didn’t realize was that his wife had stopped thinking of him as her Rescuer and had now cast him in the role of Persecutor.

My friend’s wife sought comfort with friends and coworkers who supported her Victim stance (new Rescuers). She lashed out at him in reaction to her feelings of victimization. When this happened, he felt like a Victim to her Persecutor counterattack. The two saw a series of couples’ counselors looking for rescue, but their marriage finally ended in divorce.

I added, “He was depressed and withdrawn for months after that.”

“It’s true,” said Ted, “these dramas often lead to despair. There may be times of relative stability, of course, when it seems things are under control. But living in this drama means staying alert for anything or anyone that might threaten that fragile stability. Everyone is on the defensive. Victim defends herself against Persecutor. Rescuer defends Victim from Persecutor. Persecutor defends himself against Rescuer. Exhausting!

“When you inhabit any of these three roles, you’re reacting to fear of Victimhood, loss of control, or loss of purpose. You’re always looking outside yourself, to the people and circumstances of life, for a sense of safety, security, and sanity.

“When you consider your past, which seems to be filled with Victims, Persecutors, and Rescuers, you assume that the future will be much the same. Since you’ve been a Victim before, you project that into the future, working to prevent or put off what you believe is your inevitable Victimhood. Living this way is like driving while looking only in the rearview mirror. You assume the road ahead will be just like the road behind you.

“When you accept this as the way things are, the chance of the Dreaded Drama Triangle repeating itself dramatically increases. These beliefs are often formed quite early in life. They’ve been with you so long, you’re completely unaware of them—and their power.”

I looked out at the ocean and took in Ted’s words. They felt like a tidal wave that engulfed me, as I saw how much of my life reflected the turmoil of the Drama Dynamic.

Ted continued, “Ultimately, the Drama Dynamic results in spiritual destruction. As you resign yourself to the inevitability of the pattern, your spirit suffers and gradually withers. Perhaps that’s why so many people suffer from depression. One absorbed in the Drama Dynamic sleepwalks through her days, believing that this nightmare is just the way things are.

“It’s a toxic mutation of the human relationship, and it pains me to see it played out so often. I call it the Dreaded Drama Triangle—the DDT. Do you know about DDT?”

“Isn’t that the poisonous chemical they used for years to kill insects, the one that was later banned in most parts of the world?” I said.

“Yes. It is a toxin. Banning the poisonous Dreaded Drama Triangle—the DDT—from the affairs of humankind would make the world a saner and safer place, too, don’t you think?”

Just then I heard the crashing of a wave on the beach. Glancing out at the ocean, I realized that the tide had turned. Ted noticed, too.

He said, “Before the tide comes back in, there’s one more thing I want you to know about. Let’s move up there to those rocks. I’ll show you the atmosphere the DDT thrives in. It’s called the Victim Orientation.”