Colonial-era travelers in Virginia. From Our Country by Benson John Lossing, circa 1875. New York Public Library.

CHAPTER 4

VIRGINIA’S RICH BARBECUE TRADITION

There was hardly a neighborhood in which there was not some favorite spring devoted to barbecuing purposes. The barbecue season generally commenced in May, before which time fish fries and squirrel stews were the order of the day. In every neighborhood there was some person noted as a skillful barbecue cook. The squirrel stew, when well concocted, formed a delicious repast. All sorts of savory condiments were thrown into the cauldron, and its steam was sufficient to make the mouth of an epicure fairly water.

The barbecue proper consisted of shotes and lambs, dressed with a super abundant supply of pepper, and cooked over a large fire built up in holes five or six feet long and three or four deep. Sticks were placed over these, and the shote or lamb laid on it. Vegetables in abundance were always to be had, and the foot of the table was usually graced by a ham of bacon. The table was a temporary affair, made of rough planks, laid upon scantling, and the seats were of the same character. The plates, knives, forks, dishes, pots, etc., were of course contributed by the givers of the feast, and in the evening an ox cart or two generally drove up to take all the materials home. The drink was almost entirely mint juleps, that delicious beverage which is now never had as it used to be in the days of yore.

The principal amusements were ninepence loo, quarter whist, and conversational upon all manner of subjects. It was very rare to see anybody intoxicated, and if one became so, and made himself disagreeable, he was not invited again. Neighborhoods took it by turns to give barbecues. This neighborhood would begin this Saturday, and invite the adjoining neighborhood.

That neighborhood would reply next Saturday and then a third, a fourth, and so on. Thus nearly every Saturday would witness a barbecue somewhere in the county, and it was kept up until frost came.

–New York Herald, “The Old Fashioned Barbecue in Virginia,”

April 29, 1858

For centuries, Virginia was renowned for its barbecue. Since at least the seventeenth century, barbecue has been “common to Virginia festivals.”1 When Virginians held a barbecue in East Rockingham in 1873, the newspaper described it as “Old Virginianism, in primitive style, broke out in East Rockingham, in the shape of a Grand Barbecue.”2 “The barbecue loving democracy of Chesterfield” was the name given to that county in 1878 because the people who lived there were so fond of barbecued pork and Brunswick stew.3 According to nineteenth-century authors, barbecue is “an Old Dominion Institution,” “one of the ancient and honorable institutions of Virginia” and a “rural entertainment” that was “so frequent among the country people of Virginia.” As far back as 1825, Americans considered Virginia to be barbecue’s “original habitat.”4 The word barbecue itself is a “Virginian word,” and even the practice of calling an event that features barbecued meat “a barbecue” is “good old Virginia parlance.”5

By 1841, Virginia was so well known for barbecues that people referred them as “that Virginian Saturnalia—a Barbecue.”6 Virginia barbecue enjoyed “world-wide fame,” and even people in Hawaii said that barbecue made Virginia famous.7 One writer explained in 1860 that the word barbecue “means nothing more nor less than an entertainment where hogs are roasted whole—a totum porcum process, sir! Hence to ‘go the whole hog’ is preeminently a characteristic of the people in our good old Commonwealth—God bless her—from the point of the ‘Pan Handle’ down to the depths of the Dismal Swamp.”8

Presidents George Washington and James Madison were very fond of Virginia barbecues (sometimes called “spring parties”).9 Archaeologists have even discovered a barbecue pit in Montpelier’s south yard that was in use during President Madison’s lifetime.10 Madison’s barbecues were grand events. Male servants would dress in colorful clothing with shiny brass buttons and clean aprons. Female servants would wear impressive and colorful dresses.11 Dolley Madison’s niece, Mary Cutts, wrote:

Barbecues were then at their height of popularity. To see the sumptuous board spread under the forest oaks, the growth of centuries, animals roasted whole, everything that a luxurious country could produce, wines, and the well filled punch bowl, to say nothing of the invigorating mountain air, was enough to fill the heart…with joy!…At these feasts the woods were alive with guests, carriages, horses, servants and children—for all went—often more than an hundred guests…If not too late, these meetings were terminated by a dance.12

Virginia plantation records are full of entries about barbecues that were “given in turns by owners of plantations.”13 Virginians called the period from May to October “the barbecue season.” The place selected for a barbecue was near a spring or pleasant grove. African Americans, respected for their skill at the pits as those who “rule the roasts,” did the cooking. “Hogs of middling size,” or shoats, were barbecued, as were lambs, sheep, chickens, steers and wild game. When it was time to partake of the feast, the Virginian custom was to serve women first. After partaking of the delicious meal, dancing commenced.14

Among the pleasure parties which bring together a large number of farmers in the seasons of fine weather, I shall not forget the one at which members of both sexes and of all ages are gathered. The families of a district agree to meet in the woods in the neighborhood: the site is good if there is a spring whose clear and cold water can contain the punch, beer, rum and wine. The old people, women, young people and children set out on horseback, in carriages and in wagons and proceed merrily to the meeting place. The one who is giving the feast has borrowed horses to convey the food and drink, the table service, the cooking utensils and the boards with which must be fashioned the tables and the benches. That deserted place is filled with people in an instant. The horses graze freely around the banqueting hall whose ceiling is formed by the bushy tops of beautiful trees.

Not far from there, Negroes can be seen digging a pit: others are felling trees to fill it, and soon sheets of flame will rise from that furnace: when it no longer contains anything but live coals, there will be placed thereon a half of beef, a veal and some suckling pigs, attached firmly together on the trunk of a young oak which serves as a spit. The women go by turns to the pit of live coals to baste the meats, then return to the spring to put the bottles in order. The young ladies squeeze the lemons in large porcelain bowls. The young men help the Negro boys place the plates on long tables made of boards placed on upright stakes.

The old people sit in a group on the grass and their grandchildren play around them. The married women assign themselves to all the places where the young ladies are occupied, and encourage them to work.

When everything is prepared for the dinner, the women take the right side, and the men the left. The old people of both sexes face each other. The children under the care of their nurses, have the grass as a substitute for a table and benches. Everyone eats with a good appetite and with gaiety. The men, under the eyes of their wives and watched by their children, leave the table without drinking and intoxication. The Negroes show signs of the feast; meat grease gives a gloss to their ebony cheeks, and a few glasses of rum make their eyes sparkle. Lovers meet again after the feast and take a walk into the woods to talk about their love.

Ferdinand Bayard, 1791

Colonial Virginians spent a great deal of time traveling to neighboring plantations and farms to visit friends and family who often lived long distances away. Traveling on foot, on horseback or by horse-drawn carriage meant that traversing the long distances could take days. Therefore, visits often lasted for long periods.15 As one author wrote, “[L]iving so isolated, [Virginians] are fond of company, [this] produces a course of visiting for weeks afterwards. A Virginian visit is not an afternoon merely; but they go to week it, and to month it, and to summer it.”16

After long-distance trips, travelers would be tired and hungry. When the number of visitors was large, cooking and serving foods outside was the most efficient manner of feeding the crowd, and the best way to do that was with barbecue. American missionary Hamilton Pierson commented on the efficiency of feeding people with barbecue in 1881:

It [barbecuing] is the simplest possible manner of preparing a dinner for a large concourse of people. It requires neither building, stove, oven, range, nor baking-pans. It involves no house-cleaning after the feast. It soils and spoils no carpets or furniture. And in the mild, bountiful region where the ox and all that is eaten are raised with so little care, the cost of feeding hundreds, or even thousands, in this manner is merely nominal.17

Colonial-era travelers in Virginia. From Our Country by Benson John Lossing, circa 1875. New York Public Library.

Therefore, the Virginian custom of holding barbecues was very practical, and this probably contributed to their popularity.

WEDDINGS AND FUNERALS

Two events especially suited for barbecues were weddings and funerals. On March 6, 1731, Mary Ball, George Washington’s mother, married Captain Augustine Washington at Sandy Point in Westmoreland, Virginia. The couple celebrated their wedding with barbecues, “as was the custom in those days.”18 Holding barbecues for wedding celebrations was practical because well-wishers often had to be entertained for several days or even weeks.19

Holding barbecues for mourners was also practical.20 At John Smalcomb’s funeral in 1645, mourners consumed a barbecued steer and a barrel of strong beer and used up “considerable [gun] powder.”21 In 1647, Richard Leman provided an ox for a barbecue worth the tidy sum of eight hundred pounds of tobacco. John Michael, of Northampton, took another approach. His will specified that there should be no immoderate drinking nor shooting at his funeral, which implies that there would have been had he not made his request.22 In 1675, Edmund Watts of York County also forbade the serving of drinks at his funeral. In 1678, the colonial Virginia mourners of Mrs. Elizabeth (Worsham) Epes barbecued a steer and three sheep. Along with the barbecue, the host served “five gallons of wine, two gallons of brandy, ten pounds of butter and eight pounds of sugar.”23 In 1667, Daniel Boucher, of Isle of Wight County, willed the cost of furnishing an old Virginia barbecue consisting of “one loaf of bread to every destitute person” and a barbecued ox for the “whole number of poor residing there.”24

A funeral at this time was a splendid, and for many of the attendants a highly enjoyable, occasion. The shadow of death had no place among those sunny spirits. Barbecues were given and rum liberally dispensed by the afflicted family, and a general spree was indulged in at the expense of the estate of the deceased. The more boisterous mourners usually carried their fowling pieces and fire-arms to the funeral, and after the feast and bowl had somewhat assuaged their sorrow and enlivened the solemn occasion, a barbaric celebration ensued.

Jennings C. Wise, Ye Kingdome of Accawmacke or, The

Eastern Shore of Virginia in the Seventeenth Century (1911)

There is a modern myth that discharging firearms at barbecues in seventeenth-century Virginia was illegal. According to one source, Virginians established the law in the 1690s.25 Another source notes that Virginians established the law in the 1650s.26 According to another source, the Virginia House of Burgesses passed the law in 1610.27 However, such claims are not entirely true.

Of course, the English word barbecue didn’t exist in 1610. The Virginia House of Burgesses didn’t exist at that time either and wouldn’t hold its first session until 1619. The House of Burgesses established the first gun law in Virginia in 1623. It was a response to the loss of a quarter of the population of the colony during the 1622 Indian attack. The law required all plantations to have firearms and ammunition on hand for self-defense. The House of Burgesses established the first law prohibiting the firing of guns at “drinking or entertainments” in 1631. “Entertainments” is what early Virginians often called barbecues. The purpose of the law was to conserve gunpowder and eliminate false Indian attack alarms. However, by 1655, the law had been modified to exclude weddings and funerals—two prime events for holding barbecues.28

A RURAL ENTERTAINMENT

Philip Fithian was born in New Jersey. He lived in Virginia from October 1773 to October 1774, employed as a tutor for the family of planter Robert Carter in Virginia’s Northern Neck. Fithian’s accounts of Virginians make it clear that frequent community festivals were an important part of social life. Hunter Dickinson Farish was the first to edit a work that included Fithian’s entire journal.29 Farish observed that Virginia barbecues and fish feasts were frequent and, sometimes, elaborate events that often lasted for several days. With feasting, dancing and games, Virginians from all walks of life participated in the private entertainments, including some of the most prominent Virginia families such as the Washingtons, the Lees and the Tayloes.30

BARBECUE IN VIRGINIA

Advancing, you hear shouts, merriment, and “tweedle dum and tweedle dee.” Music and dancing are near, and if there are no nymphs and dryads, pass on, and you see, glancing around, groups or constellations of ladies, such as you will see only in Virginia or Spain. These are attended by the satellites that usually follow in the train of beauty. You discover a large circular space, covered with canvass boughs, where the light of heart and foot are dancing to the violin and fife, while under the trees at a distance are the more sedate, and grave in years, sitting at tables by fours, and looking intently on little parallelograms of pasteboard, which, ever and anon, they rap down with force upon the board. You will not fail to see a range of tables that would feast a regiment, and camp fires at which all flesh and fowl is roasting, including a “whole hog,” that constitutes the barbecue which gives name to this feast.

When the banquet is ready you devote yourself to the constellations, as the first course is for the ladies, upon whom the gentlemen attend, as the genius waited upon Aladdin. The second course is for the lords, upon whom the managers and slaves attend. After all, the managers dine also, and they have servants no less exalted than the ladies. A barbecue has from three to eight hundred people, and it is only where a very social life is led that this feast could be so well filled.

J.M., New-England Magazine (January 1832): 37–45.

Courtesy of Cornell University Library, Making of America

Digital Collection.

As settlers moved farther inland, barbecues spread all over Virginia with them. In 1808, John Edwards Caldwell (son of the Revolutionary War’s “Fighting Parson” James Caldwell) shared his account of a barbecue near what is now Stephens City, Virginia, in the Shenandoah Valley.31 He described how people gathered from miles around for a day of entertainments such as conversation, dancing and feasting on “refreshments of every kind.” He ended his brief account with the observation, “A Virginia Barbicue [sic] seems a day of rejoicing and jubilee to the whole of the surrounding country.”32

In 1850, American author and artist Charles Lanman wrote that the early settlers of Virginia first introduced what we call today southern barbecue in the American colonies. As a result, Americans thought of barbecue as a “pleasant invention of the Old Dominion.”33 Writing that “it was not unnatural that the feast should eventually have become known as a barbecue,” Lanman realized that Virginians were cooking barbecue and holding barbecues even before they used the English word barbecue to describe the cooking method or the events.

A Virginia barbecue, circa 1860. From My Ride to the Barbecue, 1860.

I passed through Stephensburgh, a decayed looking village, and at Slaughter’s mills, three miles further, I witnessed a scene to me altogether novel and equally pleasing. There were assembled about 400 ladies and gentlemen, from round the country, to the extent of 30 miles, as elegantly and fashionably dressed, as good taste and good clothes could make them: they met at this place in the morning, and had been the entire day engaged in dancing, conversation or other amusements. Refreshments of every kind had been liberally provided by the guests themselves. I understood these merry meetings (termed Barbicues) were very frequent during the summer, and I observed that the hope of soon assembling at another, took the sting from adieu when about to part. A Virginia Barbicue seems a day of rejoicing and jubilee to the whole of the surrounding country.

John Edwards Caldwell, A Tour through Part of Virginia,

in the Summer of 1808 (1809)

The locations selected for Virginia barbecues were very important. A hospitable spot in a grove under the shade of trees and near a flowing spring was most preferred. One writer observed of springs, “No barbecue is complete without this rock-encased living stream of water.”34 Springs provided a source of water for soups, stews, punch, mint juleps and toddy. The spring water also kept meats cool while the fire burned down to coals and was used to chill watermelons and barrels of refreshing drinks.35 In 1851, a writer commented, “a spring of pure water is nearby, and a mint bed, fresh and verdant, is immediately contiguous,” indicating that Virginians planted mint near springs to ensure that it was readily available to make mint juleps.36

An 1811 account of a Fourth of July barbecue held in Staunton, Virginia, describes soldiers enjoying a barbecue near “Mr. Peter Heiskell’s spring,” while the civilians “enjoyed a barbecue feast at Mr. John McDowell’s spring.”37 In typical Virginian fashion, there was plenty of gunfire and many toasts made by the revelers. Dorrel’s spring in Fairfax County, Virginia, was the location chosen for many antebellum barbecues.38 A Fourth of July barbecue took place in 1809 near Fredericksburg, Virginia, at Captain Lewis’s spring after a public reading of the Declaration of Independence.39 Morgan’s spring is the site of several notable old Virginia barbecues. Alexander R. Boteler, a nineteenth-century Virginia politician and author, described it as it appeared in 1858:

At the base of the hill on which the house is situated, beneath a shelving mass of moss-grown rock and the gnarled roots of a thunder-riven oak, a glorious spring leaps out into sunlight, as if glad to be released from the dark prison-caves of earth and flowing over the smooth sides of an artificial reservoir, it runs rippling along, making merry music as it tumbles over its rocky bed into the placid waters of the lake. This is “Morgan’s Spring;” and such has been its designation for more than a century.40

In 1775, Hugh Stephenson raised a volunteer company of Virginians and gave a barbecue for them near Morgan’s spring before “making a bee-line for Boston.” Surviving members of the company (who were healthy enough to travel) met there again fifty years later to commemorate the event with a barbecue.41 In 1858, Boteler described a “mammoth poster” advertising a barbecue at Morgan’s spring that read, “Grand Civic and Military BARBECUE, At Morgan’s Springs, Near Shepherdstown, Jefferson County, Virginia, On Thursday the 2d of September, 1858. &c, &c, &c, &c.” He called the attendees “mutton munchers” and the barbecue cooks “those who ruled the ‘roasts.’”42

Morgan’s spring, circa 1860. From My Ride to the Barbecue, 1860.

At least until around the middle of the twentieth century, most Virginians who “ruled the roasts” were African Americans.43 John Duncan visited Virginia from Scotland in the early 1800s. He was the guest of George Washington’s nephew, Bushrod Washington, at a barbecue held near Alexandria, Virginia, in 1818 and commented on the fact that all of the hardworking cooks were African Americans. The barbecue took place under the shade of trees near a spring. The cooks made “tubfulls of generous toddy” with the cool spring water. The meats barbecued over hickory wood coals included fowl, pork, lamb and venison. Another lesson Duncan learned was that hosts always served women first at old Virginia barbecues. When Duncan violated that protocol, his hosts quickly put him in his place.44

After having spent an hour or two at Mount Vernon, Judge Washington politely invited us to accompany him to a Barbecue, which was to take place in the afternoon close by the road to Alexandria. The very term was new to me; but when explained to mean a kind of rural fête which is common in Virginia it was not difficult to persuade us to accept the invitation.

The spot selected for this rural festivity was a very suitable one. In a fine wood of oaks by the road side we found a whole colony of black servants, who had made a lodgement since we passed it in the morning, and the blue smoke which was issuing here and there from among the branches, readily suggested that there was cooking going forward.

Alighting from my horse and tying it under the shadow of a branching tree I proceeded to explore the recesses of the wood. At the bottom of a pretty steep slope a copious spring of pure water bubbled up through the ground, and in the little glen through which it was stealing, black men, women and children, were busied with various processes of sylvan cookery. One was preparing a fowl for the spit, another feeding a crackling fire which curled up round a large pot, others were broiling pigs, lamb, and venison, over little square pits filled with red embers of hickory wood. From this last process the entertainment takes its name. The meat to be barbecued is split open and pierced with two long slender rods, upon which it is suspended across the mouth of the pits, and turned from side to side till it is thoroughly broiled. The hickory tree gives, it is said, a much stronger heat than coals, and when completely kindled is almost without smoke.

Leaving the busy Negroes at their tasks—a scene by the way which suggested a tolerable idea of an encampment of Indians preparing for a feast after the toils of the chase. I made my way to the outskirts of the wood, where I found a rural banqueting hall and ball room. This was an extensive platform raised a few feet above the ground, and shaded by a closely interwoven canopy of branches. At one side was a rude table and benches of most hospitable dimensions, at the other a spacious dancing floor; flanking the long dining table, a smaller one groaned under numerous earthen vessels filled with various kinds of liquors, to be speedily converted, by a reasonable addition of the limpid current from the glen judiciously qualified by other ingredients, into tubfulls of generous toddy.

A few of the party had reached the barbecue ground before us, and it was not long ere we mustered altogether about thirty ladies and somewhere about an hundred gentlemen. A preliminary contillon or two occupied the young and amused older, while the smoking viands were placed upon the board, and presently Washington’s March was the animating signal for conducting the ladies to the table. Seating their fair charge at one side, their partners lost no time in occupying the other, and as there was still some vacant space, those who happened to be nearest were pressed in to occupy it. Among others the invitation was extended to me, and though I observed that several declined it, I was too little acquainted with the tactics of a barbecue, and somewhat too well inclined to eat, to be very unrelenting in my refusal. I soon however discovered my false move. Few except those who wish to dance choose the first course; watchfulness to anticipate the wants of the ladies, prevent those who sit down with them from accomplishing much themselves, the dance is speedily resumed, and even those who like myself do not intend to mingle in it regard the rising of the ladies as a signal to vacate their seats. A new levy succeeds, of those who see more charms in a dinner than a quadrille, and many who excused themselves from the first requisition needed no particular solicitation to obey the second.

John Duncan, 1823

Virginia barbecues were a reflection of the hospitality of the people of Virginia, who had a reputation for hosting grand feasts with generous portions. In an 1836 account of a Virginia barbecue, we find, “The table not only groaned with the barbecue and bacon common to Virginia festivals, but all kinds of preserves, pies, sweet meats, and floating islands, &c.”45 Such bounties explain why writers called the rush when people eagerly filled their plates with their share of the delicious “viands” “the attack.”

Virginians have barbecued untold tons of pork over the last four hundred years. They have also barbecued their share of other meats, including wild game, poultry, veal, lamb and mutton. Virginians have been barbecuing beef using the southern barbecuing technique since the early seventeenth century—longer than any other state in the Union, including Texas. The hosts of a nineteenth-century barbecue held near Fredericksburg in Bowling Green, Virginia, required five hundred waiters to serve eight barbecued oxen to the large crowd that attended.46

From the very beginnings of the colony of Virginia, sturgeon was also an important food. Isaac Weld, an Irish writer and explorer, visited Virginia between 1795 and 1797. According to him, a Virginia barbecue may have included a barbecued pig or a barbecued sturgeon:

The people in this part of the country, bordering James River, are extremely fond of an entertainment which they call a barbacue [sic]. It consists in a large party meeting together, either under some trees, or in a house, to partake of a sturgeon or pig roasted in the open air, on a sort of hurdle, over a slow fire.47

About one month after colonists first arrived in Virginia, they found sturgeon that were huge and abundant. John Smith told us that they once took fifty sturgeon at a draught and at another sixty-eight.48 The colonists were catching sturgeon that were as long as three yards. From that time, sturgeon, also known as Charles City bacon, became a very important part of Virginians’ diets. One writer noted, “When Charles City bacon was plentiful, everyone was happy.”49 Because sturgeon in Virginia’s waters grew to as much as fourteen feet long and often weighed hundreds of pounds, it’s easy to see why Virginians barbecued them low and slow just as they would a hog.50 In the 1890s, the sturgeon population in Virginia’s rivers began to dramatically decline due to overfishing, and by the turn of the twentieth century, the sturgeon population had crashed. In 1926, operators closed the last sturgeon fishing operation on the Potomac.51

Old Virginia Brunswick stew. Author’s collection.

Without Brunswick stew, originally known as squirrel stew or soup, “a Virginia barbecue would not be complete.”52 At a barbecue held at Powhatan Courthouse in 1840, an attendee recalled the “tripods made of three forks in the ground” from which were “suspended the pots of Brunswick stew, the scent of which would make any man hungry.”53 At an 1885 barbecue, the bill of fare included Virginia smoked ham, fried chicken, catfish chowder, fried fish, Brunswick stew (called squirrel soup in the account), barbecued beef and barbecued mutton.54

Virginia barbecues reminded many colonial- and federal-era eyewitnesses of Native Americans. Lanman described how Virginians barbecued meats by “laying them upon sticks across the fires” just as colonists witnessed Powhatan Indians doing in the seventeenth century. Duncan also commented on Virginia’s “Indian-like” barbecuing technique, writing, “Leaving the busy Negroes at their tasks—a scene by the way which suggested a tolerable idea of an encampment of Indians preparing for a feast after the toils of the chase.” After watching barbecue cooks near Richmond, Virginia, in the early 1800s, Colonel Thomas H. Ellis compared Virginia’s barbecuing technique to the Powhatan Indian method of cooking on a platform made of sticks.55 As late as the 1950s, Virginians were still barbecuing meats on wooden hurdles set directly over hot coals. The design of the early twentieth-century Virginia barbecue “grills” remained very similar to those used by Virginians for hundreds of years before.

According to Boteler, the cooks employed “large log fires,” or what we call today “feeder fires.” From these, barbecue cooks made embers used to replenish coals in the barbecue pit. Although some famous Virginia barbecue cooks used chestnut wood, most preferred white oak or hickory when cooking barbecue, and they were careful to let it burn down to glowing coals that had no visible smoke rising from them before putting the meat on the barbecue grill.56 Some Virginians took the extra effort to line their barbecue pits with stones.57 In addition to barbecuing meat over coals, Virginia barbecue was sometimes “cooked on the coals” as described in 1883: “The old Virginia barbacued [sic] meats are of world-wide fame, and the system is simply to cook on or near coals in the open air.”58

Since the early 1600s, Virginians have been using the classic Virginia barbecue sauce made of “vinegar, peppers, and other spicy condiments.”59 Cooks applied the sauce to meats as they barbecued. Some versions of the sauce included some type of oil, such as butter or lard. Virginians called the basting sauce “the seasoning” or “gravy” and applied it using “long switch mops”—or, as Boteler called them, “flexible wands.”60

Virginians often took a minimalist approach to barbecue. In an 1839 account of a Virginia barbecue, it is stated, “Nothing else eatable accompanies the hogs, except plain bread.”61 An example of this practice still existing today is found in the famous Virginia barbecued chicken. Virginians barbecue chicken directly over coals on an open pit, seasoning it while it cooks with an old-school Virginia barbecue sauce made of oil, vinegar, salt, peppers, herbs and spices. Generally, hosts do not serve sauce on the side with it. The color of Virginia barbecue also demonstrates the minimalist approach. The barbecue cooked in Richmond in 1849 by a ruler of the roasts named Ben Moody was cooked until it had “just enough of the brown” before it was ready to eat.62 The brown color of the barbecued meat indicates that Virginia barbecue cooks didn’t use elaborate rubs.

Cover page of My Ride to the Barbecue, 1860.

Cooks basting barbecuing meats with “flexible wands” at a barbecue in Charlottesville, Virginia, circa 1920s. Holsinger Studio Collection. Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

In colonial and federal times, well-to-do Virginians used expensive ingredients such as sugar, spices, sweet herbs, red wine and various ketchups in their barbecue recipes. Worcestershire sauce became commercially available in 1837.63 By 1844, shops in Virginia were selling it with the pitch, “This sauce possesses a peculiar piquancy, and, from the superiority of its zest, is more generally useful than any other sauce.”64 Virginians were quick to begin using the sauce in their barbecue recipes as a replacement for the mushroom ketchup they used in earlier times.

An 1844 account of Virginia barbecue describes how the cooks allowed the barbecued meat to rest: “When the roasting is completed the fire is allowed to die out, but the ox remains upon the spit…until it is time to cut up the meat for dinner.”65 Resting meat allows the fat and collagen to cool and gelatinize, resulting in a moister product. Recently, people outside Virginia have called resting barbecue a “new barbecue truth.”66 However, in Virginia, resting barbecued meats is an old barbecue truth long practiced by Virginians.

On rare occasions, some nineteenth-century Virginia barbecue cooks boiled meat before barbecuing it. An 1872 account tells us:

There were five fat mutton, two beef and veal frizzing fragrantly over the fire all morning, the sweet savor sharpening the appetite…A deep, wide ditch had been dug some three or four feet in the ground, and filled nearly with bark and dry sticks and set on fire. At one end of the ditch several large boilers were filled with the meat and parboiled. Across the other half of the trench stout green sticks were placed close together, and over the live coals the smoking embers having been raked away, was laid the meat, after having been boiled and gashed through and through. As it roasted over the fire, several Negro men were constantly busy with long switch mops, sopping a gravy of black pepper, butter, salt and vinegar from the bowls near by [sic] and saturating the browning meat as fast as it dried. Near by were great hampers of bread and cold ham, buckets of lemonade, and long tables of pine planks spread under the trees.67

Old Virginia barbecued beef. The Evening World, August 18, 1906. Library of Congress.

Boiling meat before barbecuing is an old practice. People all over the South have been boiling meats before barbecuing them for hundreds of years—they just won’t admit it.

Besides being known for pull-tender barbecued beef, Virginians have a tradition of serving higher-quality cuts of beef barbecued to the perfect doneness appropriate for the cut. An account of a barbecue held at Sandy Point in Westmorland County, Virginia, at Christmastime in the year 1900 mentions the practice. At this barbecue, cooks barbecued a deboned ox on a rotating spit rather than on a hurdle, and “one could have served at once, steak rare or well done, the rib roast, sirloin or porterhouse.”68 Barbecued brisket is a relatively new thing in Virginia. More traditional beef cuts served by Virginia barbecue cooks include beef ribs, chuck and top sirloin.

DRINKING PARTIES

Most accounts of Virginia barbecues from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries describe wholesome events with very little rowdiness or bad behavior. For example, in French traveler Ferdinand Bayard’s 1791 account of Virginia barbecues, he referred to them as “pleasure parties…without drinking and intoxication.” This indicates that the Virginia barbecues witnessed by him were wholesome festivals.69 However, that is not true of them all.

George Washington’s diary entries for a few days after he attended Virginia barbecues indicate that he was relatively idle. After one barbecue, he even felt the need to go to church. One author has noted that this could be a subtle hint that some barbecues attended by Washington were quite rowdy and that he took time afterward to recuperate.70

In 1801, the South Carolina politician Ralph Izard wrote to his mother, “In Virginia they have once a fortnight what they call a fish feast or Barbicue [sic] at which all the Gentry within twenty miles round are present with all their families.” He went on to comment, “I was very much surprised to see the Ladies young and old so fond of drinking Toddy before dinner.”71 Weld also mentioned that a Virginia barbecue “generally ends in intoxication.”72 At a 1788 Fourth of July barbecue in the Shenandoah Valley held near Federal Spring at General Wood’s Plantation, the “jovial bowl and glass went briskly round after the repast.”73 Because of the heavy drinking that occurred at some Virginia barbecues, people took to calling some of them “drinking parties.” In 1798, the architect of the United States Capitol, Benjamin Latrobe, recorded in his diary while in Alexandria, Virginia:

About half-past eight the Philadelphia company of players who are now acting in a barn in the neighborhood came in in a body. They had been at a “drinking party” in the neighborhood. Once, in Virginia, these drinking parties had a much more modest name—they were called “barbecues.” Now they say at once a “drinking party.”74

John Burke wrote of eighteenth-century Virginia barbecues:

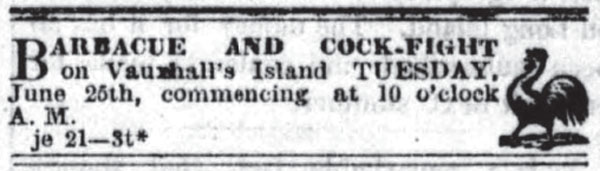

Drinking parties were fashionable in which the strongest head or stomach gained the victory. The moments that could be spared from the bottle were devoted to cards. Cock-fighting, was also fashionable. I find in 1747, a main of cocks advertised to be fought between Gloucester and James River. The cocks on one side were called Bacon’s Thunderbolts, after the celebrated rebel of 1676.75

Clearly, Virginia barbecues could get rowdy at times. In another account of colonial Virginia, we find:

At all the county towns, east of the mountains, fairs were held at regular intervals, accompanied by sack and hogshead races, greased poles, and bullbaiting. In fine weather, barbecues in the woods, when oxen, pigs and fish were roasted, were frequent, and were much enjoyed by all, ending usually, among the lower classes, with much intoxication. Another great source of delight was the cock-fight. The small farmers assembled at the taverns to play billiards and drink. The monthly sessions of the courts filled the towns with a miscellaneous crowd.76

John Kirkpatrick was George Washington’s military secretary. In 1750, he wrote to Washington complaining about life in Alexandria, Virginia, “We have dull Barbecues—and yet Duller Dances.”77 Apparently, Kirkpatrick was attending the tamer version of old Virginia barbecues. According to Washington, there was a time when Virginians made it a point of honor to send guests home drunk. In fact, Virginians had an informal “barbecue law” that held that the only excuse for refusing a round of drinking was unconsciousness.78

In colonial and federal times, Virginians would often engage in the postdinner custom called “drinking healths.” François-Jean de Chastellux (a French military officer) wrote:

These healths or toasts…have no inconvenience, and only serve to prolong the conversation…But I find it an absurd, and truly barbarous practice, the first time you drink, and at the beginning of dinner, to call out successively to each individual, to let him know you drink his health.79

Chastellux’s reaction to drinking healths is amusing, although they didn’t amuse him. He recounted how George Washington “usually continues eating for two hours, ‘toasting’ and conversing all the time.” He waited a half hour after a round of toasting before being served supper with more bottles of “good claret and madeira wine.”80 Senator William Maclay recounted one of Washington’s presidential dinners held around 1789:

Then the President, filling a glass of wine, with great formality drank to the health of every individual by name round the table. Everybody imitated him, charged glasses, and such a buzz of “health, sir,” and “health, madam” and “thank-you, sir,” and “thank-you, madam,” never had I heard before.81

By the end of the eighteenth century, drinking healths was not as popular as in earlier times. In 1788, Washington explained, “People no longer forced drinks on their guests.”82 This change in attitude toward drinking at dinnertime eventually resulted in fewer barbecues that featured heavy drinking.

Thomas Jefferson was well acquainted with Virginia barbecues. He had at least one spring at Monticello that provided a popular spot for hosting them.83 However, there are some indications that Jefferson wasn’t fond of attending barbecues. This could be because he “was a man of sober habits.” According to Peter Fossett, who lived enslaved at Monticello for eleven years until Jefferson’s death in 1826, “No one ever saw him under the influence of liquor.”84 President Jefferson even abolished the practice of drinking healths at the presidential dinner table by replacing the “barbecue law” with the “health law.” At one of Jefferson’s dinners, a Mr. Carter asked a Mrs. Randolph to drink a glass of wine with him. Jefferson informed her that she was acting against the “health law.” Jefferson then informed her that three laws governed his table: “no healths, no politics, no restraint.” In an 1802 letter, John Latrobe described to his wife one such dinner: “I enjoyed the benefit of the law, and drank for the first time at such a party only one glass of wine, and, though I sat by the President, he did not invite me to drink another.”85 Physician and politician Samuel Mitchill left us his account of dinner with Jefferson:

The dinners are neat and plentiful, and no healths are drunk at table, nor are any toasts or sentiments given after dinner. You drink as you please, and converse at your ease. In this way every guest feels inclined to drink to the digestive or the social point, and no further.86

In 1808, President Jefferson’s sister Anne Scott Jefferson attended an Independence Day barbecue in Charlottesville, Virginia. Jefferson chose not to attend. After consuming their share of the old Virginia barbecue, the men drank at least seventeen toasts.87 That many toasts would certainly have been too many for “a man of sober habits.” In reference to the event, Thomas Jefferson wrote to Ellen Wayles Randolph, “I thank heaven that the 4th. of July is over. It is always a day of great fatigue to me, and of some embarrassments from improper intrusions and some from unintended exclusions.” Sometime before 1820, Jefferson had stopped attending Virginia barbecues altogether, as evidenced by Elizabeth House Trist’s letter to Nicholas P. Trist wherein she wrote, “Mr. Jefferson had an invitation to a barbecue near Charlottesville which he declined as he had long given up attending these festivals.”88

Richmond, Virginia, barbecue advertisement, the Daily State Journal, 1872. Library of Congress.

By the end of the nineteenth century, people were not observing Virginia’s “barbecue law” as stringently as in previous years. From 1879 we read, “A Virginia barbecue of the present day is hardly so rude as such occasions used to be.”89 By 1884, the only drink served at one Virginia barbecue was coffee.90 However, in 1915 some Virginia Rotary Club members were visiting colleagues in Raleigh, North Carolina. The North Carolinians gave a barbecue for them so the Virginians could “see how the connoisseurs of the trenches prepare the stuff here [in North Carolina] without the liquid accompaniment that must always attend the Virginia barbecue.”91

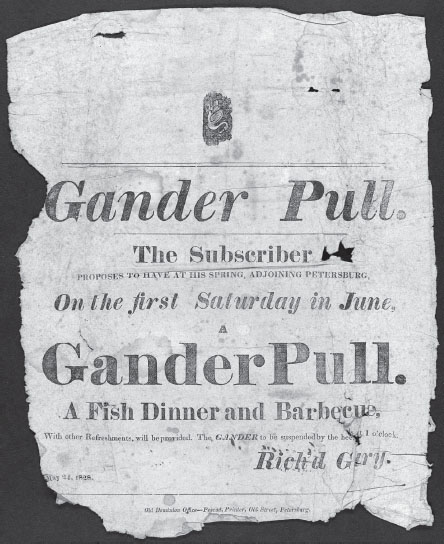

Augustus John Foster, a traveling Englishman, wrote of old Virginia barbecues in the very early 1800s that although horseracing and gambling were still a part of the festivals, cockfighting was on the decline.92 The cruel game known as a “gander pull” was also nearing its end in Virginia.93 A gander pull was a game where men on horseback would compete to be the first to pull the greased head off a goose that was hanging upside down from a limb or pole as they galloped past. As early as 1793, gander pulling contests were sparking criticism.94 A writer in 1850 wrote insultingly of some people of whom he did not approve, “They would find themselves much more at home at a Virginia ‘Gander Pulling.’”95 Starting in seventeenth-century Virginia, gander pulling contests at barbecues eventually spread all around the United States.96 The cruel game gave rise to the old saying, “Everything is lovely and the goose hangs high.”97 Some of the contests lasted as long as three hours with the same poor goose being tortured all that time. The practice was slow to die and would even linger in some parts of the country as late as the twentieth century.98 A church festival, of all occasions, held in the year 1877 in Waco, Texas, featured a gander pulling contest. The Sunday school superintendent won.99 This all happened in spite of claims made just a few months earlier that the cruel game “will not occur here [in Waco] again.”100

An advertisement for a gander pull, fish dinner and barbecue at Petersburg, Virginia, circa 1828. Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

A gander’s whole neck is stripped of feathers, and whose head is well soaped, is suspended by the feet to a strong elastic branch or twig, about the height of a man’s head on horseback; one of the company then sets off, full gallop; and the speed of his [illegible; gallop?] is urged by the application of the whips of his companions. In passing the gander, he endeavors to get hold of its head, and wring it off, the probability is, that the gander will elude his grasp; if, however, he gets hold of the head, he will either pull it off, or be dragged off his horse. In the event of pulling off the head, he is crowned victor, and the subscription money is devoured to a drinking match. If he does not succeed, another of the company follows close on his heels with equal speed, to try his fortune.

General Advertiser, “Description of a Gander Pulling,”

June 13, 1793

The cruelty of games like cockfighting and gander pulling, along with the drinking that went on at some Virginia barbecues, no doubt contributed to the negative impression of barbecues held by northerners. In 1825, a New Yorker commented, “In the minds of people in this part of the country, scenes of riot and intemperance are generally connected with the idea of a ‘barbecue.’”101

GANDER PULLING CONTEST RULES

“A gander’s head is offul hard to fetch,” he said, “and the feller what gits it will yearn what he gits; but I don’t say this to discourage any of you. I want you all to pull and show your spunk. It will add to the success of the pullin’ to have you all in it.” The rules were as follows:

First—Thou shalst not pull at the gander till thou hast paid a quarter a piece.

Second—Thou shalst ride each his own hoss and each one for hisself.

Third—Thou shalst not pull at the gander if thy hoss is not in a gallop.

Fourth—Thou shalst have five pulls at the gander for one quarter.

Fifth—If thou pullest off the hed of the said gander thou shall have $2.50 for a quarter chance and $5 for two chances.

Sixth—The hed of the said gander shall be greased.

Plain Dealer, January 14, 1879

BARBECUE CLUBS

By the middle of the eighteenth century, Virginians had officially established the first barbecue club in the history of the United States. It began early in the eighteenth century as informal meetings of community members near Richmond, Virginia. In the year 1788, members officially chartered the Buchanan’s Spring Barbecue Club.

Buchanan’s spring was located on a farm owned by Parson Buchanan about one mile outside Richmond. It was near what is today the 1000 block of West Broad Street.102 The water that flowed from Buchanan’s spring “was pure, transparent, cool and delightful, embowered under old oaks.” It was a favorite spot for barbecues “because of its fine water, magnificent shade, perfect quietude and exemption from dust.”103

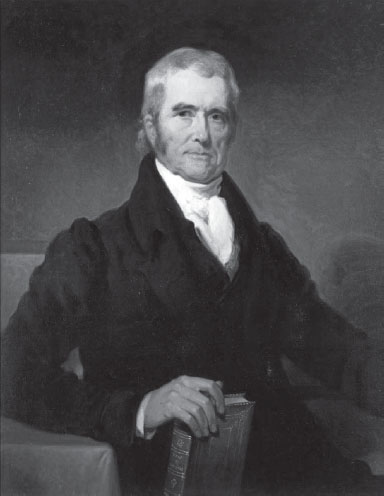

Members of the barbecue club met every other weekend between the months of May and October (Virginia’s barbecue season) in order to relax, converse, play games and enjoy Virginia barbecue. Two African Americans, Robin and Jasper Crouch, were the club’s regular “caterers.”104 Chief Justice John Marshall was a founding member of the club, and his personal records indicate that he gave generous amounts of money to support it. In 1786, on one occasion he paid nine shillings for a barbecue, seven shillings for another and six shillings for yet another barbecue that year.105

Typical club meetings consisted of playing games such as quoits and backgammon and enjoying the company of friends. Dinner was usually ready around three o’clock in the afternoon and often consisted of “a fine fat pig” that was “highly seasoned with cayenne.” An account of one meeting tells us that the barbecued mutton was “cooked to a turn,” and the pork was “highly seasoned with mustard, cayenne pepper” and had a “slight flavoring of Worcester sauce” probably imparted by mushroom ketchup.106 Desserts consisted of melons and fruits followed by punch, beer and toddy, as well as mint juleps made using the cool waters from Buchanan’s spring.107

Chief Justice John Marshall. Painting by Henry Inman, circa 1834. Library of Virginia.

The Cool Spring Barbecue Club, circa 1880. Notice the Indian-style hurdle and forked posts. From the Duke Family Papers, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

Club meetings continued at least until the early months of the Civil War, although by that time the meeting place had changed to an island in the James River. As late as 1862, “Respectable strangers, and especially foreigners, are always invited to the feast of the Barbacue,” and club members were still enjoying Virginia barbecue, toddy, juleps and quoits.108 Richmond was also home to the Clarke’s Spring Barbecue Club, established a few years after Marshall’s club.109

Colonel Richard Thomas Walker (R.T.W.) Duke Sr. was born in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1822. He was a graduate of the Virginia Military Institute. In his lifetime, he was a lawyer; the commonwealth attorney for Albemarle County, Virginia; a Congressional representative; and a veteran of the Civil War. In the period of 1899–1926, his son, R.T.W. Duke Jr., wrote in detail about Virginia barbecues held after Virginia’s Reconstruction era at his father’s estate in Albemarle County, Virginia, named SunnySide.

In the 1870s, Duke and his friends and neighbors established the Cool Spring Barbecue Club with Duke as its first president. The club met at the “Barbecue Spring” located about half a mile away from SunnySide. The spring, with its “exceedingly cold” waters and located at the foot of a hill surrounded by trees, was perfectly suited for “old fashioned Virginia barbecues,” which were held near it for longer than anyone could remember.

Duke wrote a detailed account of how the Virginia barbecue cooks worked their magic at the pits and shared their recipe for Brunswick stew. The barbecued meats included young pigs, lambs and chicken basted with a mixture of the classic Virginia barbecue baste of butter, vinegar, salt and pepper.

The Brunswick stew recipe called for squirrel when it was available. If no squirrels were available, chicken filled Duke’s pot. The stew recipe is a classic Virginia style that includes middling (described as a “streak o’fat & streak o’lean”), Worcestershire sauce, tomatoes, butter beans and red pepper. Duke commented, “You were tempted to eat so much of it, that it took away your appetite for the delicious barbecued meat.”110 Duke’s accounts also make it clear that the club still observed Virginia’s barbecue law.

There are many long-held and wonderful barbecue traditions in the United States, but Virginia’s is the longest. Virginia’s barbecue traditions set the standard for southern barbecues and provided the model for them all throughout the South. Because Virginia is “the Mother of Commonwealths,” “the Ancient Dominion,” “the Old Dominion,” “the pride of the Union,” “the nursery of Republican statesmen” and “the Mother of the South,” it is easy to see how Virginia’s influence and barbecue tradition spread throughout colonial America.111

“A GANDER PULL!!!”

You’ve heard of cock-fights-baits of bull—

Did you ever, of a Gander pull?

If you havn’t, I have, so I’ll tell,

And mind you understand me well.

A pole is cut, tall, limber, sound—

And one end fastened to the ground;—

A fork about the middle’s placed,

And ’tother end is upwards raised.

A rope from upper end’s let loose

And holds the legs of the gander or goose,

Whose neck is of its plumes released,

And then made slick by being greased.

One on each side, with whip in hand,

To urge the horses, takes the stand—

And now all preparation’s done,

Each rider mounts—and now the fun!

Bestride on horse, or mule, or ass,

Each round the circle swift doth pass,

And as each comes by the goose quite,

Gives her a pull with all his might;

Who straight doth squall, but squalls not long,

For death soon interrupts her song.

And now the crowd full of delight,

Gaze on enraptured at the sight;

And in each changing of the game

Join in the laugh and loud acclaim.

Here comes a whiskered son of man,

The foremost of the hopeful clan,

Who gives a pull both hard and long,

That head must come were neck not strong.

His knees rise o’er his donkey’s mane,

And neck as arched as a crane;

His stirrups short, his heels appear

Far out behind his horse’s rear.

With six inch spurs he is supplied,

But can’t for life, touch horse’s side.

Next rides a youth, with no less grace,

With sanguine hope marked in his face—

A mouth that might tempt fair one’s kisses—

So eager, lo! the head he misses,

And passes on—and close beside

Comes something like a man astride.

At this unlucky time, alas!

The goose doth squall—the horse won’t pass—

And whip, and spur, and cane, and curse,

But tend to make the matter worse,

For backward, like a crab he goes,

His rump where ought to be his nose.

Next comes a Yonker on a mule,

His beast, by much, the lesser fool,

With pendent ears and meekest face

That well attest his honored race.

His gait is borrowed from the snail,

And nothing moves him but a frail.

The knowing ones back well his rider,

Whose face is marked with grog or cider;

Whose heaving chest is full and wide,

And well his brawny arm was tried,

His hair hung flowing o’er his face,

His nose was in the proper place—

His head too was on nature’s plan,

Upon the shoulders of a man.

And round and round they move amain,

And pull and pull, but all in vain.

(A head of twenty summers’ growth

To leave its parent stock is loth.)

While some were landed in the dirt,

Some tore a coat and some a shirt;

And once our friend of the long hair

Had been suspended in the air

Before the manly sport was done—

Before the prize was lost and won.

At last a waiter-jointed fellow,

With countenance savage, meagre, sallow,

Having slyly roughed his soapy hand

By rubbing thoroughly with the sand,

Stretching thin as any slab—

Reached up and gave the head a grab,

And bore it down upon his hip

With claws of a most giant grip—

With clenched teeth and glaring eyes

He bore away the bleeding prize.

The earth did tremble with the shout,

And thunders seemed to burst about.

“Huzza!” was heard on every side,

And rode the victor in his pride.

Ye that have witnessed no such scene

Have not been blessed as I have been:

And should you hear of one about

You’ll go and see—yourself—no doubt.

Good-night unto you old and young,

Just read the song which I have sung;

And should it not be neat and plain

Then are my labors all in vain.

Robert Francis Astrop, Original Poems, on a Variety of Subjects, Etc. (1835)