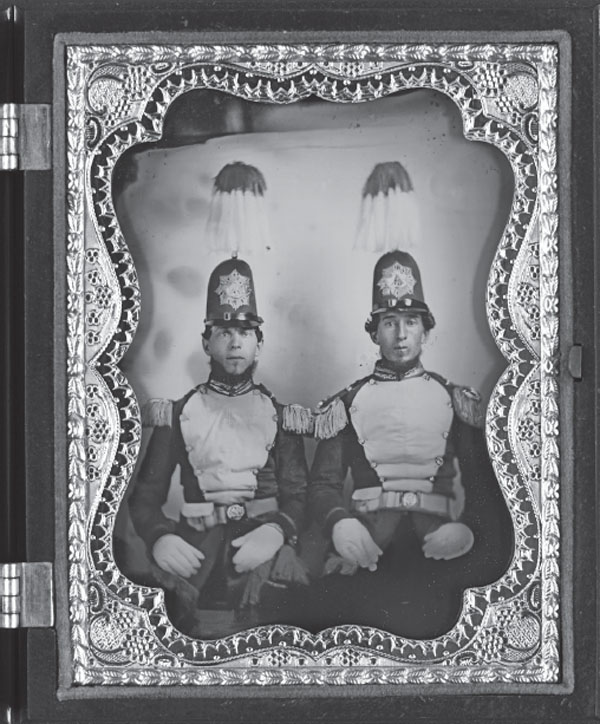

Two unidentified soldiers of the Richmond Light Infantry Blues, circa 1862. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-37395.

CHAPTER 6

VIRGINIA’S NINETEENTH-CENTURY BARBECUE MEN

Juba—whose face is blurred stands in front & to the side of her [his wife Mandy]. With the death of these Negroes the art of “barbe’cuing” has welnigh passed away, only Caesar Young—my servant—surviving to remember the art. He is one year younger than I am & when Caesar goes, as far as Albemarle is concerned the “barbecue” will practically go out of existence—that is the barbecue in its best form.

–R.T.W. Duke Jr., Recollections (courtesy the University of Virginia, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library)

There was a time when Virginia barbecue was famous all over the country and around the world. Thirty thousand people were enticed to attend a barbecue held in 1856 outside Boston by advertisements that Virginia barbecue cooks were preparing the barbecue.1 In 1897, the Saint Paul Globe reported plans for an “old-fashioned Virginia barbecue” at the Minnesota state fair that year.2 In 1900, organizers of the World’s Fair in Paris, France, chose Virginia barbecue cooks to represent American barbecue cooks.3 In 1909, more than thirty thousand people enjoyed “a Virginia barbecue” in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.4

Today, history has forgotten most of the names of the countless Virginia barbecue cooks who have lived over the last four centuries. However, those people who did the hard work of digging the trenches, chopping the wood and staying up all night ruling the roasts are who made Virginia barbecue famous.

The first barbecue cooks in Virginia were either enslaved Native Americans or Native Americans employed by colonists. Later, the job of cooking barbecue transitioned to indentured servants and enslaved Africans and African Americans. By the early nineteenth-century, Virginia’s barbecue men had opened barbecue restaurants long before the first recorded barbecue restaurant in North Carolina opened in 1899. In fact, the earliest American restaurant known to advertise barbecue on the menu did so in 1798 in Alexandria, Virginia.5

RICHARD STRATTON

Richard Stratton began cooking Virginia barbecue and Brunswick stew in the year 1869. One of his satisfied customers boasted, if you have never tasted Brunswick stew cooked the way “old Uncle Dick” prepared it, you “have not yet tasted one of the most savory dishes known to the human palate.” Just as other Virginia barbecue cooks of his era, Stratton used to lay hickory sticks across a pit filled with hot coals in order to support the barbecuing meats. Stratton’s happy patrons also raved about his Virginia-style barbecued sheep, which “was as sweet as the tenderest venison.”6

WILLIAM “BLACK HAWK” HAISLIP

Around the turn of the twentieth century, “an aged white-haired native of Spotsylvania Courthouse” known as “the best barbecue cook in the state” was William Haislip—or, as his friends called him, Black Hawk. By the turn of the twentieth century, Black Hawk was eighty years old and was often the master of ceremonies at large barbecues in Virginia. Like so many other Virginia barbecue cooks, he was very proud of his skill at the pits and boasted that he was “the only man in the state competent to cook a whole ox properly.” In 1900, Black Hawk invited President William McKinley to one of his barbecues held in October of that year. Black Hawk, we are told, “had no trouble seeing the President.”7

In 1855, the People of Fredericksburg and the surrounding counties held a Fourth of July barbecue. So much food was served that it required twelve cooks working two days to prepare it and one hundred and fifty waiters to serve it. The bill of fare illustrates why Virginia barbecues were so famous.

| 8 Saddles Mutton | 16 Fore Quarters Mutton | 20 Roasted [barbecued] pigs |

| 32 Quarters of Shoat | 8 Shoat Hind Hashed and Stewed | 26 Fore Quarters of Lamb |

| 20 Hind Quarters of Lamb | 500 Chickens | 16 Quarters of Veal |

| 4 Veal Heads—Stewed | 30 Hams of Bacon | 20 Pieces of Beef (10 lbs. each) |

| 750 Loaves of Bread | 6 lbs. Black Pepper | 50 lbs. Lard |

| 60 lbs. Butter | 10 Bushels Potatoes | 6 Bushels Beets |

| 5 Bushels Onions | 320 Heads of Cabbage | 10 Gallons of Vinegar |

| 120 lbs. Crushed Sugar | 1 Gallon Currant Jelly | 3 lbs. Mustard |

| 1 Gallon Sweet Oil | 2 Boxes Lemons | 150 Quarts Wine |

| 40 Gallons Whiskey | 14 Bottles Brown Stout | 6000 Feet of Lumber for Tables |

Fredericksburg Herald, July 9, 1855

JASPER CROUCH

Jasper Crouch was a famous caterer in Richmond, Virginia, during the early 1800s known for his skill in barbecuing shoats and for his old Virginia toddy.8 He was the barbecue cook and “major-domo” for the Buchanan’s Spring Barbecue Club and the Richmond Light Infantry Blues. The Richmond Light Infantry Blues, also called “the Blues,” was formed sometime around the year 1790 and often hosted festive gatherings. A famous relic at outings hosted by the Blues was their thirty-two-gallon punch bowl known as “his majesty.” Crouch, as the “special attendant of his majesty,” often filled it with punch, julep or toddy. Crouch made his famous punch with “four-fifths of brandy to one of rum” and just a splash of Madeira. A bowl one-third full of ice cooled the sweet mixture. Crouch’s hospitality and kindness “could not be surpassed.” Crouch’s delicious barbecue was often “highly seasoned with mustard, cayenne pepper” and mushroom ketchup. When Jasper Crouch died, the Blues buried him with full military honors.9

Two unidentified soldiers of the Richmond Light Infantry Blues, circa 1862. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-37395.

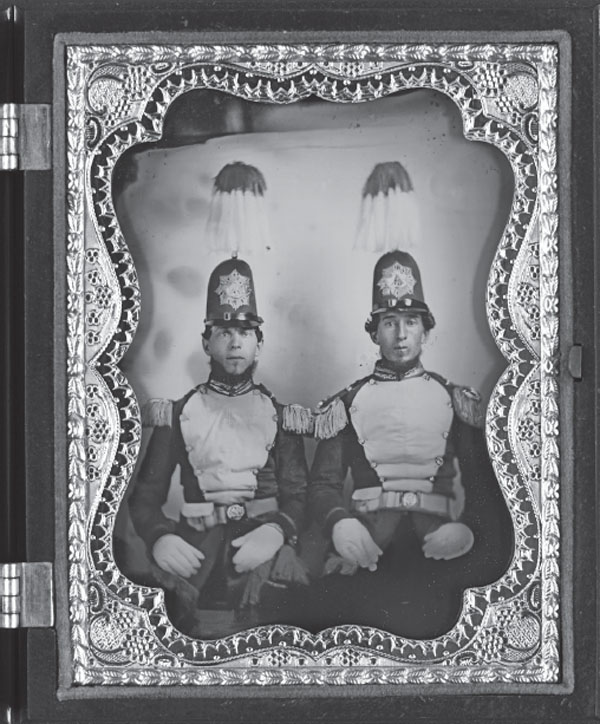

CHARLES W. ALLEN

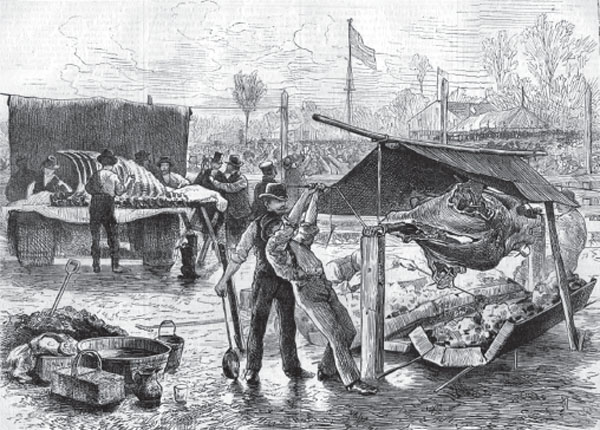

Charles W. Allen of Lexington, Virginia, was a highly sought-after Virginia barbecue cook in the late nineteenth century. Described as a mulatto man who knew “all that is to be known about conducting a barbecue,” he was much in demand all over the eastern United States.10 He was about fifty years old in 1894 when hired to travel to Boston to prepare an old Virginia barbecue feast hosted by Father John Cummins in Boston, Massachusetts. Cummins was determined to bring one of the “real old Southern festivities” to Boston. To ensure that outcome, he hired Charles Allen, a Virginia barbecue cook. Allen and his team of six assistants barbecued a one-thousand-pound ox and several shoats. His wife and his brother, Joel, assisted him. Allen continued as Cummins’s barbecue cook for several years at his “genuine old time Virginia” barbecues that he hosted in Boston.

Allen employed two methods for barbecuing an ox, and both methods took about twelve hours to complete. One of Allen’s techniques was to barbecue the ox by spitting the carcass on a large tripod. He would then barbecue it “feet up” with the interior filled with corn, sweet potatoes and other vegetables.

His other technique was to split the ox carcass much as a hog is split before barbecuing it. He would then lay the carcass on the barbecue grill directly over burning coals. He and his assistants would fasten a pipe lengthwise in the carcass, and with the help of ropes and pulleys, four men could move the ox into just about any position Allen desired. Allen and his cooks would use a knife to make incisions in the meat that were filled with salt, pepper and other secret ingredients, much as some in our times inject meats before barbecuing them. He also basted the meat with a “savory sauce” made from a secret recipe that he claimed to have acquired from a famous French chef; that claim was probably an embellishment.11 In 1897, Allen cooked “the largest ox ever barbecued in Boston.”12 If true, that must have been a very large ox. In 1895, Allen barbecued an ox in Boston that weighed more than 1,400 pounds.13

Charles W. Allen, the Boston Herald, August 27, 1894. Boston Public Library.

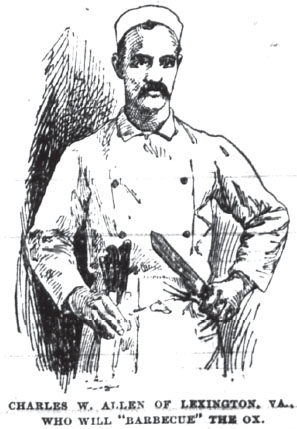

Beef being barbecued nineteenth century style, referred to as the “ox roasted whole.” From Harper’s Weekly (November 11, 1876).

The official program for Father Cummins’ Sixth Annual Barbecue, circa 1899. Boston Public Library.

JOHN DABNEY

John Dabney, born in Hanover County, Virginia, in 1824, was “a celebrated cook and caterer” in Richmond, Virginia, who was described as “universally polite and courteous.” Author Thomas Nelson Page wrote that Dabney “was the best caterer I ever knew.”14 For many years, he managed nearly all of the big barbecues given in and around the Richmond area. He was “the best man living to mix mint juleps” that had “the real old Virginia flavor.”15 Dabney’s mint juleps were so delicious that they were literally fit for royalty. During his visit to Richmond, Virginia, in 1860, the Prince of Wales, who would become King Edward VII, praised Dabney’s mint juleps.16 Dabney was “a real old-fashioned Virginia cook,” and he, like Jasper Crouch, often prepared meals for the famed Richmond Light Infantry Blues.17

Sometime before the start of the Civil War, Dabney purchased freedom for himself and his wife. He was allowed to make payments over time for the agreed-on amount, which he did until the entire debt was paid. During the war, Dabney continued to make payments on the debt he owed. By the end of the Civil War, he had paid the full amount for his wife’s freedom but still owed several hundred dollars for his own. However, because Confederate money became worthless as the war progressed, his old master asked him to discontinue payments until after the war was over, which he did.18

At the close of the Civil War, even though all formerly enslaved people were free, Dabney felt that he still owed several hundred dollars to the person who had enslaved him. In spite of the financial difficulties of the times, by 1866 he had saved enough money to repay the debt he believed that he owed and delivered it to his former master. She returned the money to him with the explanation that he was free either way now and owed nothing. Nevertheless, Dabney insisted that she accept the money because, he explained, he was always taught to pay his debts.19 Interestingly, although Dabney prospered, his former master was “in indigent circumstances” after the war.20

“Mint Julep” from How to Mix Drinks, or The Bon-Vivant’s Companion, 1862.

Before the start of the Civil War, Dabney owned several Richmond restaurants, which gave him the reputation of being “unquestionably one of the best and most artistic purveyors in this country.”21 In 1862, he opened “a first-class restaurant” called the Senate House Restaurant on Eighth Street in Richmond.22 Another of his restaurants, named the Dabney House, was located on the south side of Franklin Street and near Fourteenth Street.23 He closed it just after the end of the Civil War and quit the restaurant business to become a full-time caterer until opening another successful restaurant in 1870.24

In 1859, Dabney was given two silver goblets inscribed with the words, “Presented to John Dabney by the citizens of Richmond” as “a mark of their appreciation of his courteous behavior and uniform politeness.”25 John Dabney died on June 7, 1900. One of his sons, Milton, took over his catering business.26 The people of Richmond felt the loss of Dabney well into the twentieth century.27

GEORGE BANNISTER

In an 1885 edition of the Richmond Dispatch, there is an advertisement for a restaurant on 15 North Thirteenth Street in Richmond, Virginia.28 The proprietor was a nineteenth-century Virginia barbecue man named George Bannister. His advertisement boasted of his renowned turtle soup and barbecued Charles City bacon, which is what Virginians used to call sturgeon. His hot slaw and baked beans were famous as well.29 In 1903, he served his famous Virginia barbecue and Brunswick stew for the fortysecond anniversary of the Fighting Fifteenth Virginia Infantry regiment’s deployment during the Civil War.30

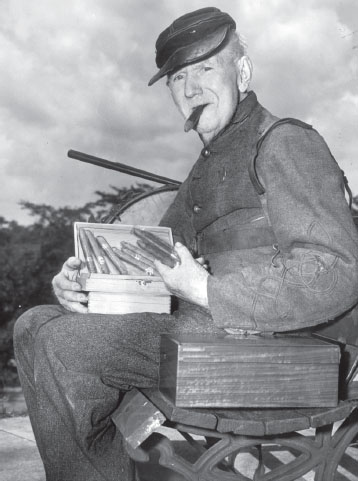

Bannister was born in 1848. During the Civil War, he served as a drummer boy for the Forty-Ninth Virginia Infantry Regiment. He joined up when he was about fourteen years of age. After the war, he became a restaurateur and caterer in Richmond, Virginia. Over the years that followed, Bannister played a part in every Civil War memorial parade held in Richmond until his death in 1949 at the age of 101. He lived to become the oldest living Confederate veteran in that city.

In 1886, after a winning night of gambling, an attacker shot Bannister in an attempted robbery.31 In 1941, he claimed that he didn’t realize that the gunman’s bullet had hit him until the next morning, when he found the bullet in his coat pocket. A gold badge that he wore on his chest, one of his many awards, saved him by acting as a shield. However, in an 1886 version of the account, it states that he was shot in the left breast and left forearm.32 At any rate, in spite of the scuffle and gunfire, the would-be robber fled empty-handed.33 Although he may have engaged in gambling on occasion, in 1941 Bannister still claimed that he had “never tasted liquor,” although he was charged with selling it on Sundays on several occasions and fined for keeping his establishment open on Sunday at least once.34 If how a man treats others is the ultimate judge of his character, Bannister was a good man. His employees expressed their respect for him in 1893 when they presented him with a Knights of Pythias badge as a token of their appreciation.35

George Bannister’s April 25, 1885 Richmond Dispatch advertisement for barbecued Charles City bacon. Author’s rendering.

George Bannister distributing cigars to new fathers on Father’s Day in 1947, from the Richmond Times-Dispatch.

A few months before he died in 1949, Bannister reminisced about his life as a young man. His most vivid memories of the Civil War were of General Robert E. Lee. Recounting the time that the general complimented him on his drum playing, he began to sing:

George Bannister lived a long and eventful life, and he enjoyed the respect of his family, friends and colleagues. He is also one of the men who helped make Virginia barbecue famous in his times. It’s hard to say just how much of the cooking Bannister personally did. Following the custom of his times, he probably employed African American cooks who were experts at preparing old Virginia barbecue. However, he most certainly influenced the recipes, and by all accounts, the barbecue and Brunswick stew prepared by him and his cooks was among the best in the country.

SHACKLEFORD POUNDS

A result of the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1901–2 was the disenfranchisement of poor people, especially people of color. If a man couldn’t pay the poll tax, he couldn’t vote. However, Confederate veterans of the Civil War were exempt from the tax. Nevertheless, soon after the new state constitution was established, officials turned away Shackelford Pounds, a heroic African American veteran of the Civil War, when he attempted to register to vote in his Pittsylvania County, Virginia, voting precinct.

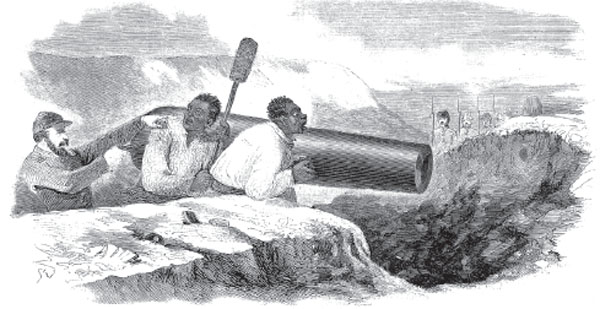

In 1861, Frederick Douglass commented on the many African Americans in the Confederate army who, at the time, were serving as cooks, servants, laborers and soldiers.37 In our times, neo-Confederates cite Douglass’s comments in an effort to insinuate that African Americans willingly fought for the principles of the Confederacy. However, it is a stretch of logic to think that slaves would risk life and limb fighting to remain enslaved. According to an enslaved man named John Parker who fought for the Confederacy at Bull Run, slave owners often forced African American men to serve as Confederate soldiers.38 Although a freeman by the time the Civil War started, Shack was aware of the consequences that might have resulted in his refusal to serve in the Confederate army.

A Confederate soldier forcing enslaved men to serve as soldiers in the Civil War. From Harper’s Weekly (May 10, 1862). Reprinted with permission of Applewood Books, Carlisle, MA, 01741.

Pittsylvania County, Virginia Courthouse, circa 1930s. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, HABS VA,72-CHAT,1--1.

By the 1850s, Shack was “a first-class barbecue cook,” often preparing barbecue all over the Pittsylvania County region of Virginia. He was also a popular barbecue cook among North Carolinians, as they, too, often called on him to come to their state to cook old Virginia barbecue.

At the start of the Civil War, the commander of the Thirty-Eighth Virginia Regiment, Captain Jones, enlisted Shack to be the cook at his headquarters. Shortly thereafter, the regiment endured heavy fighting. Although he performed his cooking duties well, when the bullets started flying Shack dropped his cooking utensils and took up a musket. However, he would never fire it. Whenever he went to the battlefield, Shack went there to save lives, not to take them.

When Shack saw a man fall from a Minié ball or shrapnel, he would rush out in the rain of bullets, take up the wounded man and carry him to the rear. He cared for each man until he was transported to a field hospital. Witnesses say that Shack never once dropped his musket in spite of dodging bullets and artillery fire as he carried wounded man after wounded man to safety.

Shack endured the entire war by saving, cooking for and caring for wounded men. When there was a break from fighting, he joined other soldiers in target practice and did “as good shooting on the firing line as any man in the old Thirty-eighth Virginia Regiment.” At Appomattox, Shack joined the line with all the other soldiers and wept as he surrendered his musket. However, unlike the other soldiers, Shack was probably shedding tears of joy because he knew that the South’s defeat meant the end of slavery.

During Reconstruction, Shack became a farmer while continuing to cook barbecue. However, on the day that officials tried to rob him of his right to vote as a citizen and veteran of the Civil War, there just so happened to be several other Confederate veterans there who had also come to register to vote. About a dozen of them recognized Shack. Upon hearing that officials had turned Shack away, they were incensed. One of the men rushed up to the clerk with tears in his eyes demanding that he register Shack to vote, declaring, “By thunder, he shall register as a Confederate soldier, for no braver one followed old Mars’ Bob…from Bethel to Appomattox.” Surrendering to the demands of the angry crowd, the clerks registered Shack as a voter with no further questions asked.39

THOMAS GRIFFIN

AN “OLD VIRGINIA” BARBECUE

The first glance satisfied us that an old fashioned Virginia Barbecue was on foot. We were soon conducted into the depth of the forest, and on a gentle slope we enjoyed the grateful sight of the feast which was to refresh the travelers. Across a pit filled with burning coals were suspended two fine porkers (“leetle hogs,” as a venerable French friend of ours was wont to call them)—they were put on early in the morning, and at 4, P.M. were still getting brown. Hard by were delightful silver-perch caught in the mill-pond;—but the pride and boast of the feast was the huge and ponderous iron pot, in which steamed with delightful fragrance a “Brunswick Stew”—a genuine South-side dish, composed of squirrels, chickens, a little bacon, and corn and tomatoes, ad libitum. The whole kitchen department was under the direction of the venerable ‘Uncle Ben Moody,’ to whose skill and taste, after a full and eager discussion of the subject matter around the snowwhite table cloth, an unanimous vote of thanks was tendered by the company. Before, during, and after the abundant meal, there was a running accompaniment of the violin—on which “Scott” and “Manuel,” happy Negroes, with red flannel shirts and their whiskered faces begrimed with coal dust, performed alternately with most wonderful perseverance and enthusiasm. The music was, of course, not very scientific; but the tune was so excellent, and the airs spirit-stirring—so much so, that the little Negro boys, standing around, caught the inspiration, and ‘heeled and toed’ it, amidst a cloud of dust themselves had raised!

Alexandria Gazette, September 14, 1849

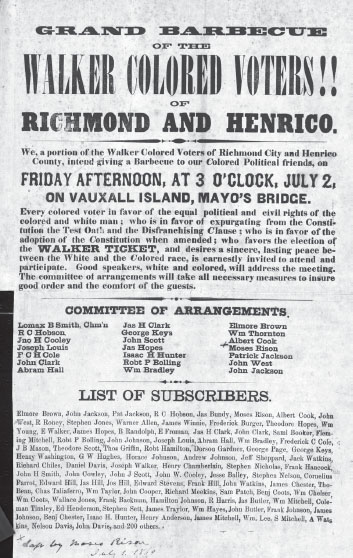

On July 1, 1869, Moses Rison, a member of the Committee of Arrangements, was distributing flyers in Richmond, Virginia, advertising a “Grand Barbecue of the Walker Colored Voters!! Of Richmond and Henrico.” Organizers scheduled the grand barbecue for Friday, July 2, at three o’clock in the afternoon on Vauxhall Island, located in the James River in Richmond, Virginia.40

By 1869, Virginia was on the verge of being reaccepted into the Union. The economy was in shambles, and the Old Dominion was still struggling to recover from the effects of the Civil War and Reconstruction. From the start of the war to the end of the Reconstruction era, big barbecues in Virginia were rare. That made the Vauxhall Island barbecue even more enticing.

The Vauxhall Island barbecue was meant to foster “a sincere, lasting peace between the White and Colored race.” A large banner was prepared depicting a Caucasian and African American shaking hands with the slogan, “United we stand, Divided we fall.”41 Orators were to give political speeches on Vauxhall Island. Hosts were to serve the barbecue on nearby Kitchen Island.42 Colonel James R. Branch, a candidate for the Senate, was there to speak about his desire to unite whites and African Americans in the interest of both races. As Moses Rison distributed the flyers on July 1, 1869, no one would have imagined that the highly anticipated barbecue would end in tragedy before it even started.

On the day of the barbecue, hundreds of people arrived in the hopes that they could participate. The barbecue committee had distributed tickets for the event. Organizers instructed the police to allow only ticket holders across the narrow footbridge to Vauxhall Island from nearby Mayo’s Island. By the time 175 people had crossed the bridge, Colonel Branch realized that many supporters remained on Mayo’s Island who couldn’t attend because they didn’t have tickets. Colonel Branch made his way to the bridge and began to cross over it. He beckoned to the police when he was about halfway across to let the rest of the crowd cross over the bridge.

As the eager crowd rushed the bridge, the weight of so many people on it at one time caused it to collapse. Suddenly, there were as many as fifteen people trapped beneath heavy timbers in danger of drowning. Dazed from a severe blow to his head, Colonel Branch struggled in the water to free himself from the debris. Several men rushed to rescue him. As they got close enough to reach him, their combined weight caused the debris that trapped Branch to sink under the water, and he drowned. Five others would die of their injuries that day.43

Colonel Branch’s death so saddened the people of Richmond that his funeral procession was almost two miles long. His friends and colleagues met on July 5, 1869. They drafted a written resolution that reads, in part, “[W]e could not have asked a nobler fate for our lamented friend than that his gallant, generous life should end with a sacred effort to inaugurate peace between the races in his native State.”44

“Grand barbecue of the Walker colored voters!! of Richmond and Henrico County,” broadside, 1869. G73, Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia.

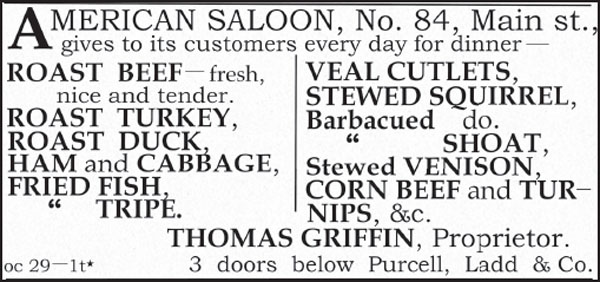

Thomas Griffin’s barbecue advertisement from the Daily Dispatch, 1853. Author’s rendering.

The man who made Vauxhall Island known for barbecues and parties was “a freeman of color” named Thomas Griffin. For years, Griffin enjoyed a reputation as the “long and favorably known Restaurateur and caterer for the public.”45 In 1853, “the hospitable and whole-souled” Griffin was the proprietor of a Richmond restaurant named The American Saloon, No. 84, located on Main Street. Griffin specialized in barbecued shoat, barbecued squirrel, barbecued shad and Brunswick stew (what he called in those days, stewed squirrel), all of which was prepared in “true Virginia hospitable style.”46

By 1859, Griffin had opened another restaurant by the name of Tom Griffin’s Restaurant, and he was advertising his catering services for “[w]edding parties, public dinners, clubs, parties, etc.” In 1860, Griffin opened an establishment on Vauxhall Island.47 The barbecue and Brunswick stew that he served there were so popular that by 1864, people were calling Vauxhall Island “Griffin’s Island.”48

Thomas Griffin was born in Williamsburg, Virginia, in the year 1791. In 1812, he moved to Richmond, where he lived for sixty years and became one of the most popular restaurateurs in the city. He died on May 28, 1872, at the age of eight-one.49 In 1881, a writer for the Daily Dispatch wrote fondly of “the past glories of old Tom Griffin’s incomparable concoctions,” paying homage to Griffin’s old Virginia barbecue and Brunswick stew.50

It’s difficult to say whether Thomas Griffin was the pit master at the fateful Vauxhall Island barbecue. However, it’s equally difficult to think that he played no role in such an important event that was to take place on “Griffin’s Island.” Perhaps a clue lies in the long list of names on Moses Rison’s flyer. Found under the heading “List of Subscribers” is the name Thomas Griffin.51

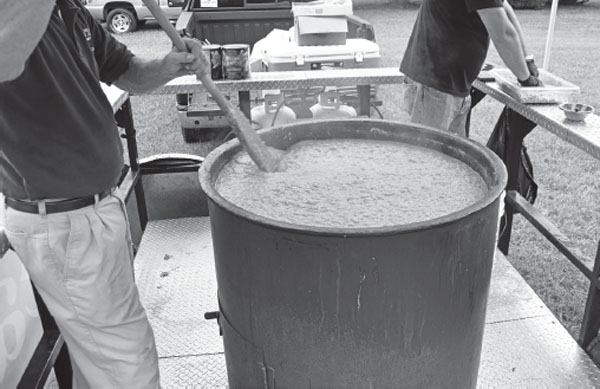

BILLY GARTH, CAESAR YOUNG AND JOHN GILMORE

In 1921, the University of Virginia celebrated its centennial with an old Virginia barbecue. Organizers cleaned up the “old Barbecue Grounds back of the Cemetery” and dug a 150-foot-long barbecue pit needed to barbecue forty shoats and lambs. They also served two hundred gallons of Virginia Brunswick stew. Among the organizers of the event were William (Billy) Garth, known as the “prince of barbecuers,” and Billy Duke. Two of the lead cooks were Caesar Young and John Gilmore. As late as 1931, Billy Garth was still serving his Virginia barbecue after basting it with vinegar, pepper, salt and butter, just as Virginians had been doing since the seventeenth century.52

Brunswick stew events are a centuries-old Virginian tradition. The Proclamation Stew Crew of Brunswick County, Virginia, cooks hundreds of gallons of stew for special events and charity fundraisers every year. Author’s collection.

Billy Garth of Charlottesville, Virginia, was more of a barbecue cook supervisor than a hands-on barbecue cook. One of Garth’s ancestors, Elijah Garth, was the famous pit boss at an Independence Day barbecue in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1808.53 Many dignitaries attended, including relatives of Thomas Jefferson. The author named no other barbecue cooks in that account. However, in the late 1800s, R.T.W. Duke Jr. mentioned a famous barbecue cook named Juba Garth. Juba and his wife, Mandy, gained their freedom at the end of the Civil War. Because fathers passed barbecuing skills down to their sons, it is highly probable that Juba’s ancestors were among the barbecue cooks at the 1808 barbecue in Charlottesville.

John Gilmore was born in 1857. Caesar Young was born in 1854. Caesar was the son of an enslaved woman named Maria. Maria claimed that John Yates Beall was Caesar’s father. During the Civil War, Union authorities in New York accused Beall, a white man, of being a Confederate spy and arrested him. They hanged him there in February 1865.

Young and Gilmore gained freedom from slavery at the close of the Civil War, after which they became celebrated barbecue and Brunswick stew cooks.54 They were also lead cooks at barbecues held by the Cool Spring Barbecue Club. Rather than simply placing shoats, lambs and chickens on hurdles over the coals, Young and Gilmore tied the carcasses “to two green poles about 6 or 7 feet longer than the pit was wide,” which made the job of frequently turning the meat easier. Each carcass had two assistant cooks assigned the job of frequently turning it as it barbecued. Another cook, called the “baster,” anointed the meat with the original old Virginia barbecue sauce made of vinegar, butter, salt and pepper using “long handled swabs” that had been dipped in the vinegary sauce kept in buckets beside the pit. As one of the pit masters explained, the heat from the coals “drove the sauce in.”55 Several forked posts made of tree limbs driven into the ground surrounded the barbecue pit. The forked posts suspended the poles that supported the meats above the pit, just as Virginia’s Indians had done for centuries before.56

The “continuous performance” of basting and turning the meat at a barbecue in Charlottesville, Virginia, circa 1920s. Holsinger Studio Collection. Special Collections, University of Virginia Library.

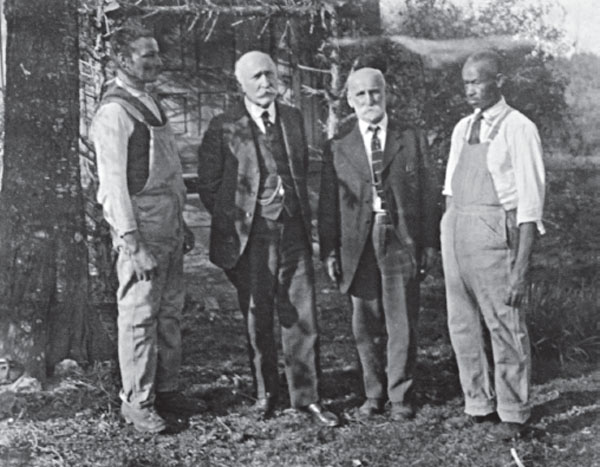

Caesar Young, Judge R.T.W. Duke Jr., W.R. Duke and John Gilmore. Lucy D. Tonacci.

In their times, the team of John Gilmore and Caesar Young were known as the finest Brunswick stew cooks in the region. One author wrote, “John and Caesar hand the palm to ‘Oscar’ of the Waldorf on Hollandaise sauce but they will spot him cards and spades when it comes to Brunswick stew.”57 Caesar Young died on Christmas Eve 1935 at the age of eighty-one. John Gilmore was eighty years of age when he died in Madison, Virginia, in 1937. Just as was predicted by R.T.W. Duke Jr., with the death of Caesar Young and John Gilmore, although barbecues continued to be popular in Virginia, the grand old Virginia barbecues were almost entirely gone.