1752 Barbecue in Woodstock, Virginia, displays its logo on signs and menus that depicts early pioneers and settlers in the Shenandoah Valley who contributed German and Scotch-Irish influences to Virginia cookery. Craig George.

CHAPTER 7

VIRGINIA

THE MOTHER OF SOUTHERN BARBECUE

A beautiful grove was selected. Plank was laid down for a dancing floor, with a platform for the musicians, and a large number of boards were laid down on logs for seating the crowd. For cooking the meats, a long trench was dug, in which a fire of seasoned wood was made, and whole sheep and shoats were placed over the fire by means of sticks run through them. Men were employed for hours to attend to the cooking and turning the meat, and in basting with pepper, vinegar and salt. Meat prepared this way is very delicious. The feast when prepared consisted of these meats with bread, pickle, tomatoes, together with cakes, pies and jellies. All were free to partake, and people assembled from quite distant places.

–H.H. Farmer, Virginia Before and During the War (1892)

Virginia supplied the southern and western United States with untold thousands of pioneers and settlers. Historian James Winston observed, “What the New England states have been by way of a nursery from which home-seekers have gone to settle the Middle West, that Virginia has been to the states of the South and the Southwest.”1 As a result, Virginia’s influence on the United States up to the end of the nineteenth century is not “approached in importance by that of any other Commonwealth in the Union.”2

Between the years 1830 and 1840 alone, no fewer than 375,000 Virginians moved west. “At this rate,” wrote educator Henry Ruffner in 1847, “Virginia supplies the West every ten years with a population equal in number to the population of the State of Mississippi in 1840.” From 1790 to 1840, Ruffner continued, Virginia had “lost more people by emigration, than all the old free States together.”3 As more and more Virginians moved west, Virginia itself paid a price as its sons and daughters departed. The author of an 1825 letter to the editor of the American Farmer wrote:

The revival of lower Virginia is now looked upon as near at hand. You know what a depopulating tide of emigration has set from it to the West for the last 20 years. Many of its former inhabitants are now enterprising, respectable citizens of North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Kentucky, Missouri, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and Ohio. There is scarcely a neighborhood in any of the new states, which has not some family from old Virginia.4

When Virginians left Virginia, they took their way of life with them, preserving some aspects of their Virginian culture and adapting other parts of it to their new home. This was demonstrated by a Virginian “pioneer and maker” of Arkansas named Barnett Wilson. Wilson held himself in the “ranks of old time Virginians bound by the laws of old time Virginia hospitality.” As result, he often hosted dinners that he couldn’t afford because of the “law which bound him.” In his Arkansas home, “he maintained every form of Virginia life, and died a true Virginian.”5

Although Virginians moved to new lands, their influence didn’t result in a replication of Virginia’s culture. Rather, they contributed ideas, customs and institutions in their new homes that persist to this day.6 One of those institutions is Virginia barbecue.

“No taste for a barbecue!” exclaimed Major Heyward. “You surprise me, Mr. Fennimore; no taste for a barbecue! Well, that shows you were not raised in Virginia. Time you see a little of the world, sir; there’s nothing in life equal to a barbecue, properly managed—a good old Virginia barbecue.”

Hall, James. The Harpe’s Head a Legend of Kentucky.

Philadelphia, PA: Key & Biddle, 1833.

Even though northerners loved Virginia barbecue, the South embraced it and made the dish its own. As Virginians established farms and plantations in other colonies and, later, in other states, they continued to host Virginia’s rural entertainments and barbecues.7 Before long, barbecuing in the Virginian manner became barbecuing in the southern manner. This is evident in old accounts of southern barbecues all over the South, from the way cooks dug the pit; the hickory sticks used as a grill; the vinegar, salt and pepper baste; and the required cool spring. No wonder people have called Virginia “the Mother of the South.”8

Proponents of a South Carolina barbecue origination theory argue that barbecue was introduced to mainland North America first in what is today South Carolina through a collaboration of Native Americans and the Spanish conquistadors who occupied Santa Elena in the last half of the sixteenth century.9

The South Carolina origination theory is strongly rooted in the hogs brought to Santa Elena by the Spanish. Because you can’t have barbecue without pork (according to some), they make the case that barbecue must have first originated only after pigs were available. However, as has been discussed, barbecue in the United States has always referred to “an ox or perhaps any other animal dressed in like manner.”10 In addition, Mary Terhune defined barbecue as “[t]o roast any animal whole, usually in the open air.”11 In 1898, another author wrote, “In America a kind of open-air festival, where animals are roasted whole, is styled a Barbecue.”12 Because pork is not a requirement for “real” southern barbecue everywhere in the South, hogs are not vital to southern barbecue’s existence.

The first domestic hogs in what is now the United States came with the Spanish to Florida in 1540. Hogs didn’t arrive in Santa Elena until 1566. Although Indians who traded with the Spanish, or those enslaved by them, may have cooked pork using Indian techniques, the Spanish abandoned the Santa Elena colony in 1587, and none of that colony’s hogs survived its demise.13 In reality, Native Americans were barbecuing meat for centuries before the Spanish briefly showed up with their hogs, but they weren’t cooking southern-style barbecue, even if they did eventually barbecue Spanish pigs. Santa Elena–style pork barbecue, if it existed at all, ceased to exist when the Spanish abandoned the colony. In addition to those facts, there are few, if any, early eighteenth-century accounts of life in South Carolina that mention barbecues like those found in accounts of Virginia during the same era.14

In 1773, William Richardson attended a barbecue and horse race in Charleston. His account indicates that the barbecue was a failure. He wrote to his wife about the “quarter of beef” that was “nicely browned” not by the coals in the barbecue pit but rather by clouds of dust. He also complained about the dirty tablecloths and remarked that the “two Hogs & Quarter of Beef” were the color of “a piece of Beef Tied to a string & dragged thro’ Chs Town [Charleston’s] streets on a very dry dusty day & then smoke dried.” The barbecued hog had “blood running out at every cut of the Knife.”15 Although not appetizing, notice that those South Carolinians served beef at this early South Carolina barbecue, which contradicts the modern notion that barbecue in the Carolinas must be made with pork.

By 1778, South Carolinians had worked out the barbecue thing. Revolutionary War veterans, some of whom were Virginians, who lived around Beaufort at that time were fond of hunting clubs and barbecues. For several years, they maintained a “barbecue house” that was eventually destroyed by a hurricane in 1804.16 Of course, it’s difficult to believe that people in South Carolina independently developed barbecue customs that were almost identical to those that Virginians had been practicing for over one hundred years before. It’s no coincidence that the first large-scale migration from Virginia, which occurred in the 1700s, was predominately to the Carolinas and Georgia. There can be little doubt that the four native-born Virginians who served as South Carolina’s congressional representatives in the years 1795–97 were successfully employing their Virginian way of politicking with barbecues in South Carolina.17 At any rate, it appears that South Carolina barbecue is a latecomer in the history of southern barbecue. As late as 1801, the idea of a barbecue seemed to be a new thing to the South Carolina senator Ralph Izard (born in Charleston, 1741) when he wrote, “In Virginia they have once a fortnight what they call a… Barbicue [sic].”18

VIRGINIA BARBECUE IN NORTH CAROLINA

When settlers first moved into what is today North Carolina, it was known at that time as Virginia’s Southern Plantation.19 The first permanent white settler in North Carolina was a Virginian by the name of Nathaniel Batts.20 In the early 1650s, Batts built a home at the western end of the Albemarle Sound and recorded the first deed in the region. By the 1660s, five hundred Virginians had joined Batts as settlers there.21

In 1662, the Virginia Assembly appointed Virginian Samuel Stephens as the “Commander of the Southern Plantation.” In 1663, King Charles II granted eight loyal subjects the territory of Virginia between latitudes 31° North and 36° North from the Atlantic to the South Seas. With the appointment of Virginian William Drummond as the first colonial governor of Albemarle Sound, the colony of Carolina was officially established.22 However, as late as the year 1700, the population of settlers in Carolina was still only around eleven thousand people compared to fifty-nine thousand in Virginia.23

As Virginians moved into the region that would become North Carolina, they took their customs with them, including Virginia barbecue. The modern eastern North Carolina barbecue sauce, which is little more than a mixture of vinegar, salt and peppers, clearly exhibits characteristics of Virginia’s original barbecue sauce. North Carolinians love that particular sauce so much that they now claim it as their own, even though its origins are in colonial Virginia.

From the nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, North Carolinians enjoyed their share of authentic Virginia barbecue. North Carolinians often hired the famous Virginia barbecue cook Shackleford Pounds to cook Virginia barbecue for them. The Times Dispatch records that in 1905 at Oak Grove Church in Northampton County, North Carolina, “an old fashioned Virginia barbecue was served, which was greatly enjoyed by the large attendance.”24

1752 Barbecue in Woodstock, Virginia, displays its logo on signs and menus that depicts early pioneers and settlers in the Shenandoah Valley who contributed German and Scotch-Irish influences to Virginia cookery. Craig George.

VIRGINIA BARBECUE “GONE TO KENTUCKY”

In 1806, family, friends and neighbors gathered in Kentucky for an old Virginia barbecue feast to celebrate the wedding of two native Virginians. They enjoyed a generous spread of good things that included bear meat, venison, wild turkey, ducks and eggs. However, the pièce de résistance was a sheep barbecued old Virginia style. The cooks placed it on a hurdle over a pit filled with glowing coals. The appointed “ruler of the roasts” covered the meat with green boughs “to keep the juices in.” Gourds full of peach syrup and honey served as sauce for the meat. The table was made of puncheons cut from solid logs, and the next day, workers used them to construct the floor of the newlyweds’ cabin. The happy couple was Tom and Nancy Lincoln, the parents of Abraham Lincoln.25

Kentucky became the fifteenth state in the Union after separating from Virginia in 1792. Some Virginians went to Kentucky in search of land and prosperity. Others went there to escape trouble. For example, officials wrote “Gone to Kentucky” beside the names of several delinquent taxpayers from Buckingham County in 1787.26

Historians have well established that Kentucky received its barbecue tradition from Virginia. Tom and Nancy Lincolns’ wedding celebration is an example of how Virginians introduced barbecue there. Even The Kentucky Encyclopedia notes, “The earliest settlers from Virginia brought the cooking and social tradition of barbecue to Kentucky.”27 Mint juleps were a favorite drink served at Virginia barbecues well before they were popular in Kentucky. This explains the Kentucky tradition of making mint juleps at barbecues. When Virginians moved to Kentucky, they also took the tradition of planting mint near springs, which provided a ready supply of it to make cool mint juleps at summertime barbecues.28

Thomas Lincoln, Abraham Lincoln’s father, Born in Rockingham County, Virginia, 1778. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-19418.

VIRGINIA BARBECUE IN GEORGIA

In the nineteenth century, Georgians called Wilkes County, Georgia, “the Barbecue Country.” It is a long-held Georgian tradition that the very first barbecue ever held in Georgia took place in Wilkes County sometime in the eighteenth century. For decades, the people of Wilkes County held two or three barbecues per week during the summer months. People would meet at some “delightfully cool and shady place” with “a spring nearby” because “no barbecue is complete without this rock-encased living stream of water.”29

Wilkes County barbecue cooks dug pits in which they burned hickory wood down to glowing embers. They kept a feeder fire going beside the pit used to replenish the coals during the cook. Hog and sheep carcasses were “speared through by hickory limbs” and placed over the coals. One Georgia pit master’s secret was to dip the barbecued meats in large dishes of a mixture of butter and vinegar that was highly seasoned with salt and pepper before serving them.30

It’s not difficult to recognize the similarities between Georgia barbecues and Virginia barbecues of the same era. The spring, the shady grove, the old Virginia barbecue baste, the hickory and the hurdle made of hickory sticks are all telltale signs of Virginia barbecue influences. There is a very good reason for those striking similarities.

Many Virginias moved to Georgia, especially after the end of the War for Independence. Virginians from Westmoreland County, Virginia (an area in Virginia where barbecues were very popular in colonial times), established the first settlement near the city of Washington in Wilkes County in 1774—which, by the way, is an area in Virginia where barbecues were very popular in those days.31 In the 1780s and 1790s, people from all over Virginia were arriving in Wilkes County. The Virginian migration to Georgia continued for many years, and by the 1850s, parts of Cherokee and Cass Counties had become known as “Little Virginia.”32

Historian Ellis Merton Coulter wrote of Virginians who settled in Georgia that they were “a remarkable group…whose importance is hard to overestimate.”33 The Virginian influence on Georgia’s history is reflected in Wilkes County barbecue customs. In recognition of their Virginian roots, Georgians used to hold what they called “old Virginia barbecues.” In an advertisement for a barbecue held in Augusta, Georgia, in 1840, we find:

The Barbecue today, will be strictly after the old Virginia style, in the olden time, those therefore who intend to participate should not go unprovided [sic] with a knife, with which to, “cut their way,” into the delicious legs of mutton &c., which will be served for the occasion.34

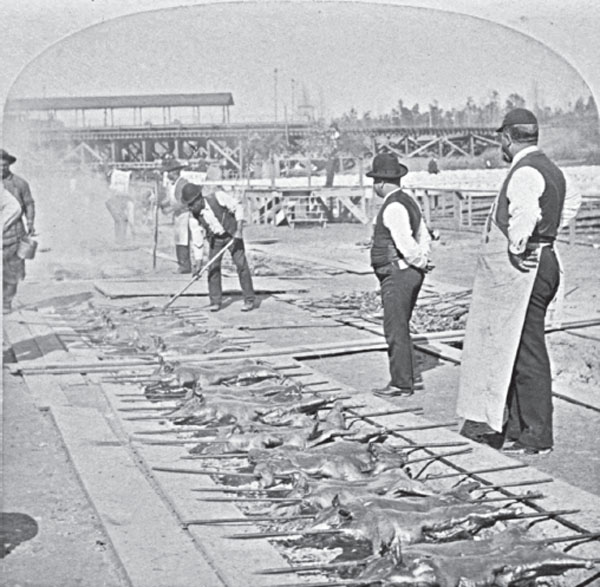

Georgia barbecue in Atlanta, 1896. New York Public Library.

In 1840, the citizens of Baldwin County, Georgia, assembled to appoint delegates to an anti–Van Buren convention. One of the resolutions made by those Georgians reads:

Resolved, That the meeting indicate the Old Virginia Barbecue as the mode of offering our hospitality to the Convention.35

Describing a Georgia barbecue he attended in 1826, author George Darien wrote of his stay in Georgia while visiting a friend there who was from Virginia. While enjoying his friend’s “true Virginian hospitality,” he accepted an invitation to a barbecue held the following day. After enjoying the barbecued meats followed by speeches, the attendees turned to playing sports, including foot races, wrestling and rifle shooting. At one match, sixty men gathered with their rifles for a chance to win a pail of apple toddy.36 The Virginia influence on this Georgia barbecue is easy to identify. The Georgians had even picked up the habit of discharging firearms at barbecues, just as Virginians had been doing since the early 1600s.

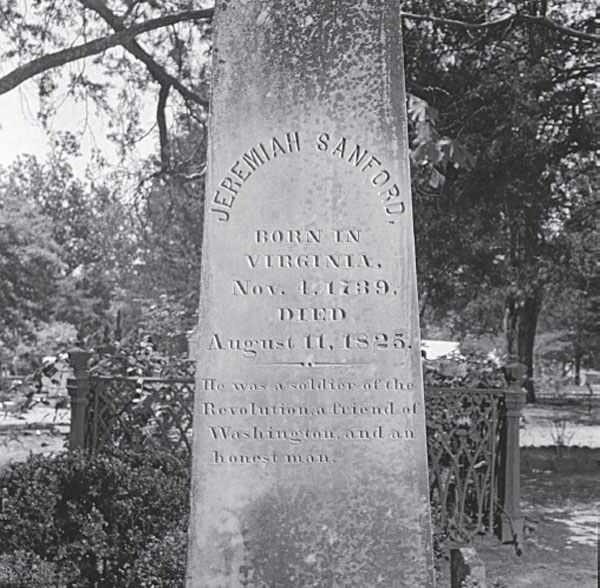

Gravestone of an early Virginian settler of Greene County, Georgia. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USF34-044333-E.

Like North Carolinians, Georgians also claimed Virginia’s original barbecue sauce recipe, as well as Virginia’s barbecuing technique. Just as was done in Virginia, “roast pig and Brunswick stew” became an oftused expression when advertising Georgia barbecues.37 An article in an 1896 newspaper reads, “Kill and dress a fat Georgia pig and roast whole over a bed of wood coals. While cooking, baste with a sauce made of butter, vinegar, pepper and salt. Serve with an apple in its mouth. This is Georgia’s dish de resistance.”38 Of course, Virginians developed that recipe long before James Oglethorp led the first settlers to Georgia in the 1730s.

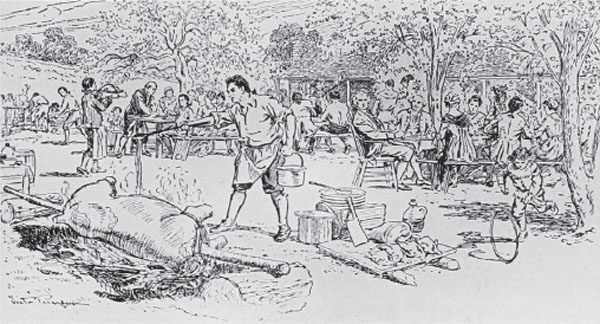

A barbecue at Augusta, Georgia, circa 1866. Sketch by Theodore R. Davis from Harper’s Weekly (November 10, 1866).

VIRGINIA BARBECUE IN TENNESSEE

The first settlements in Tennessee were the North Holston settlement in what is today the county of Sullivan and the South Holston settlement in what is today the county of Washington. Virginians settled both of those regions because they believed at the time that they were a part of Virginia. Consequently, Virginians were the first to settle Tennessee.39 Virginians would also lead the first settlements in Middle Tennessee in the years 1779–80. Therefore, it should be no surprise that Virginian James Robertson, born in Brunswick County in 1742, is considered to be the “Father of Tennessee.”40

An illustration of a barbecue hosted by John Sevier in 1780. From Stories of American History by Wilbur Fisk Gordy, 1917.

The first governor of Tennessee was a Virginian by the name of John Sevier. Born in 1745 in Rockingham County, Virginia, Sevier and his family relocated to Fredericksburg, Virginia, when he was young in order to escape the threat of Indians. In Fredericksburg, Sevier was educated in the same schools as George Washington.

In the 1790s, Sevier moved west and eventually settled in what is today Sullivan County, Tennessee. Sevier would show himself to be a natural leader, warrior and brawler. As Sevier gained prominence among the backcountry settlers, he delighted in hosting Virginia barbecues for them. His barbecues featured oxen “roasted whole” accompanied by horse races and were most festive at weddings and other celebratory occasions in keeping with Virginia’s customs. The barbecue feasts were set under the shade of trees. Venison, wild fowl, bear meat, beef, Virginia hoecakes, hominy and applejack were some of the foods served.41

Virginians continued to move west through Tennessee and on into Arkansas. The first Fourth of July barbecue held in Phillips County, Arkansas, occurred in 1821. Just like barbecues in Virginia, it took place near a spring “where a fine quality of Kentucky mint had taken hold.” One of the earliest settlers and leaders in the area, a Virginian named W.B.R. Horner, gave the address for the occasion.

Horner was from Falmouth, Virginia (aka Hogtown). Living in Arkansas from the time that it was still a part of the Louisiana territory, he was the principal figure in the creation of Phillips County. He spent his time in Arkansas “with all the courtesy and dignity of old Virginia life.” In the traditional Virginia fashion, revelers made many toasts at the Independence Day barbecue, followed by the discharge of three to nine guns.42 There should be little doubt that a Virginian from an area in Virginia known as Hogtown took his barbecue traditions with him.43

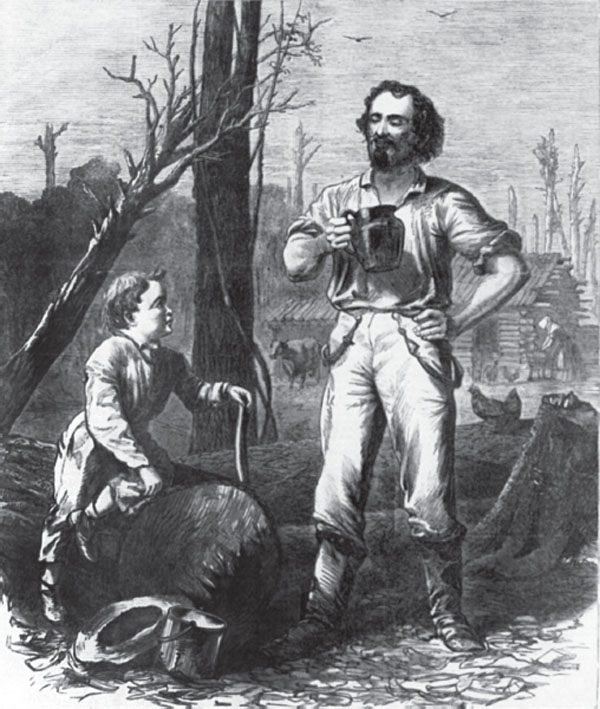

“The Pioneer” from Harper’s Weekly (January 11, 1868). Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-78067.

VIRGINIA BARBECUE “GONE TO TEXAS”

Many Virginians left for Texas to find prosperity. Many went there to escape trouble in Virginia. The practice was apparently so prevalent that sheriffs in Virginia resorted to simply writing the initials “G.T.T.” (slang for “Gone to Texas”) on official papers regarding such cases.44

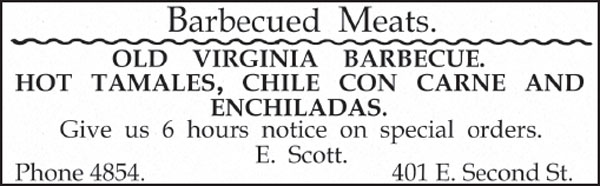

In the early twentieth century, there was a restaurant in El Paso, Texas, located at 401 East Second Street run by a fellow named E. Scott. Scott used to run advertisements in the local newspaper in which he listed his menu of hot tamales, chile con carne and enchiladas. However, the first offering above all others at the top of Scott’s menu was “OLD VIRGINIA BARBECUE.”45 In addition, just as Virginians had been doing for more than one hundred years before, by 1913, the people of El Paso had even started their own barbecue club.46

Southern barbecue was popular in Texas long before the famous barbecue restaurants in central Texas opened at around the turn of the twentieth century. It came to Texas along with settlers from the east. Many came from Virginia. Others came from Kentucky, Missouri and Tennessee, and most of those settlers were descended from Virginia families. In 1885, as much as 75 percent of the population of Texas in the western and southwestern regions was descended from Virginians.47 No wonder the president of the State Society of Texas-Virginians requested that all ex-Virginians attend “Virginia Day,” celebrated in 1899 at the Texas State Fair.48

Virginia’s influence on Texas lingers to this day. There are more than thirty counties and towns in Texas named after Virginians. At least seventeen Virginians sacrificed their lives at the Alamo, and seven more died at Goliad.49 The first American-born governor of the Mexican territory of Texas was Henry Smith, born in Virginia in the year 1788.50 At least twelve of the fifty-nine signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence were native-born Virginians.51 The “Father of Texas,” Stephen Austin, was also a native-born Virginian. The first president of the Republic of Texas was a native-born Virginian by the name of Sam Houston.52 Peter H. Bell, the third governor of Texas, was born in Culpeper County, Virginia, in 1812.53 Even the capital of Texas bears the name of a native-born Virginian. No wonder E. Scott was cooking old Virginia barbecue in El Paso.

Old Virginia barbecue for sale in El Paso, Texas, in 1914. From the El Paso Herald, July 18, 1914. Author’s rendering.

One of the most important people in El Paso, Texas, in the 1800s was a Virginian named Zachariah Taliaferro White. White arrived in El Paso, Texas, in 1881 with $15,000 sewed into the lining of his vest for safekeeping. That money was the seed money that would finance White’s vision to grow El Paso from a town of fewer than 1,000 people in 1881 into a thriving city of close to 1 million people just under forty years later.

White was born in Amherst County, Virginia, in 1850. His family had deep roots there that went back to the early decades of the seventeenth century. When White was thirty years of age, he learned that the convergence point of railroads from all directions was focusing on El Paso, Texas. That is what brought him to the little town. Through White’s vision and spirit, El Paso became a thriving modern city.54 E. Scott’s old Virginia barbecue is recognition that Virginians like Zach White brought their barbecue to Texas and that Texans strongly embraced it.

Virginians in Texas were eager to share their barbecue, apparently. Randolph B. Marcy was an officer in the United States Army in the 1850s. While traveling through Texas, he encountered a “Texas-Virginian” named Mr. McCarty. He wrote the following:

In 1854 I passed over this road again and stopped for dinner at a plantation owned by a Mr. McCarty, from Virginia, who, upon my arrival, seemed highly delighted to see me again, remarking that if I had only notified him I was coming that way, he would have given me the biggest barbecue that country had ever seen.55

In 1883, Alexander Edwin Sweet wrote a detailed account of a barbecue in Texas. The cooks didn’t barbecue the meat using the western technique of burying meat with hot rocks. Nor were they cooking it in a Texas-style horizontal smoker. They were cooking Virginia-style barbecue.56 Here is a list of the Virginia barbecue influences:

• all kinds of meats were barbecued, not just beef;

• people came from miles away to attend;

• the event was held near a spring;

• African Americans did all of the barbecuing;

• the meat was basted with Virginia’s mixture of butter, vinegar, salt and pepper;

• long, rough pine tables were constructed;

• the meat was barbecued directly over hot coals;

• no sauce was served on the side, just bread and meat;

• ladies were served first; and

• so much food was served it was said that the table “groaned.”

Sweet’s description of the 1883 Texas barbecue sounds very similar to descriptions of Virginia barbecues from as early as two hundred years before Texas became a part of the Union.

We arrived on the barbecue-grounds at about ten o’clock. More than two thousand people had already arrived, some from a distance of forty to fifty miles,—old gray-bearded pioneers, with their wives, in ox-wagons; young men, profuse in the matter of yellow-topped boots and jingling spurs, on horseback; fair maidens in calico, curls, and pearl-powder, some on horseback, others in wagons and buggies. These, with a liberal sprinkling of howling, bald-headed babies in arms, made up the crowd that met in a shady grove on a hillside to participate in the barbaric rites of the barbecue.

A stand had been erected for the speakers. Around it the ladies were provided with seats borrowed from a neighboring schoolhouse. To the left was a rough pine table, forming the four sides of a square, each side of which was two hundred and fifty feet long. It was calculated that one thousand people could at one time dine around this “ample board.” At some distance from the stand a deep trench, three hundred feet long, had been dug. This trench was filled from end to end with glowing coals; and suspended over them on horizontal poles were the carcasses of forty animals,—sheep, hogs, oxen, and deer,—roasting over the slow fire. The animal being skinned and cleaned, the whole carcass is placed about two feet above the coals, and cooked in its entirety.

The process is slow, taking twelve hours to cook an ox. Butter, with a mixture of pepper, salt, and vinegar, is poured on the meat as it is being cooked. It is claimed that this primitive mode of preparation is the perfection of cookery, and that no meat tastes so sweet as that which is barbecued.

When sufficiently roasted, the carcasses are carried on poles, manned by stalwart Negroes, and placed on small tables inside the square formed by the dining-tables. Here a force of carvers soon cut the meat into slices; others distribute it on plates, and arrange these plates on the long table, a huge slice of corn-bread being apportioned to each plate. That is all.

The dinner is served. No long bill of fare to hesitate over; no knives, no forks, no napkins; nothing but bread and meat. Water in barrels was brought from a spring at the foot of the hill. These barrels placed around the tables at intervals, a single drinking-cup being attached to each, provided the guests with the only beverage allowed on the grounds.

The ladies were admitted to the table first, and dined standing up. The doctor was horrified to see an excited female leave the table, approach a male friend, and, after whispering in his ear, return to the table with a villainous-looking bowie knife, ten inches long, in her hand. The doctor thought he detected fire in her eye, and intimated, that, if she were not quickly suppressed, blood would be spilled. But there was no murder in her heart. She merely borrowed the knife that she might cut her “chunk” of meat into reasonable mouthfuls.

After the ladies had dined, the men were turned loose on the eatables. To see them, in their rude playfulness, scramble for a choice rib,—the victor going off gnawing it ; the unsuccessful one pouncing on a waiter carrying a large trayful of beef, and relieving him of his load in a second,—forced one to think of one o’clock in a menagerie.

There was enough and to spare for all the vast crowd; and I would be lacking in my duty as a veracious reporter of the event if I failed to say, that “the hospitable board fairly groaned beneath the load of good things,” etc. The dinner was free to all; and more than twenty thousand greasy fingers testified their owners’ appreciation of the eatables, and gave at least one-third of the guests a reasonable excuse to get off that venerable truism about fingers being made before forks,—to get it off, too, as if it were a happy and original thought that had just then occurred to them.

Alexander Edwin Sweet and J. Armoy Knox, On a Mexican Mustang,

through Texas, from the Gulf to the Rio Grande (1883)

VIRGINIA BARBECUE IN THE MIDWEST

In 1796, Virginians established the town of Chillicothe, which was to become the first capital of Ohio. Soon after its founding, Chillicothe became the “fountain head of Old Dominion culture west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.”57 Settlers built the town on a land grant owned by Virginian Nathaniel Massie. Before he died, Massie had established fourteen towns in what would become the state of Ohio.58 One year later in 1797, Virginian Thomas Worthington arrived in Ohio and would become the “Father of Ohio statehood.”59 Virginians, known as the “Virginia Clique,” became a powerful group in Ohio in the early nineteenth century. By 1850, there were 85,762 Virginians living in Ohio. That number excludes deceased Virginians who were living in Ohio before 1850. It also did not count their children and grandchildren who were born in Ohio.60

Although settling far away from their home state, Virginians in Ohio continued to practice their Virginian way of life. In 1836, a traveler passing through Chillicothe wrote of a Virginia barbecue held there, “We did not expect great things here, so far from the seaboard. But, the table not only groaned with the barbecue and bacon common to Virginia festivals, but all kinds of preserves, pies, sweet meats, and floating islands, &c.”61

As early as 1798, Virginians were settling in what is today Missouri. As was the case in other regions, Virginians played a key role. People eventually called an area of central Missouri comprising thirteen counties “Little Dixie.” However, according to the authors of Bound Away, due to the number of Virginians living there, it was more like Virginia than the Deep South.62 A writer for the Springfield Republican highlighted the Virginian roots of barbecue in Missouri in 1906:

In the venerable days when Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee were contributing to the steady stream of sturdy men and women who settled on Missouri to make glad this land with the manners and customs of the old South, the barbecue was preserved as a traditional and sacred institution.63

Uncle Bill Mulkey arrived in Missouri “before Kansas City was on the map.” In 1899, he recounted the first Thanksgiving feast in Kansas City’s history that took place within what would become the borders of the city. Sitting in an office on the second floor of the Hall building on Ninth and Walnut Streets, Uncle Mulkey rested his feet, wearing his “old style boots braced against the window sill,” and recalled the details.

“It was a sort of a barbecue affair,” started Uncle Mulkey. Gazing down in a seemingly absent-minded way, he recounted that the barbecue occurred in 1864 “in Tom Smart’s pasture,” which “was in this same eighty.” When asked what “in this same eighty” meant, he replied:

Pioneer life in Missouri in 1820. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-69024.

Virginia barbecue advertised in Kansas City, Missouri. From the Kansas City Star, January 1, 1946. Author’s rendering.

This same eighty that this building is on—Old Tom Smart’s pasture was over there on Twelfth Street, about Twelfth and Holmes, I guess. It was this side of the old fair grounds…there wasn’t any building where we are now. What buildings there were in town were down on the river and this up here about the Junction was still in the woods. There were a few residences as far out as Twelfth Street. There was no railroad then, but steamboats came up the river.

Uncle Mulkey told of the barbecued beef and barbecued sheep. He also mentioned, “The brewery man’s wife was sent off the grounds because she ‘hollered’ for Jeff Davis. The war wasn’t over then, you know, and there were a lot of soldiers, Union soldiers, at the barbecue.”64

The Tom Smart mentioned by Uncle Mulkey was none other than Judge Thomas Smart of Jackson County.65 Thomas Smart was born in Virginia in 1806. He arrived in Missouri around the year 1834 with his brother, James. He owned property that was “bounded by 11th, 12th, Main, and Grand Avenue.” Therefore, the first Thanksgiving barbecue held in what would become Kansas City was a Virginia barbecue hosted by a Virginian. Tom Smart’s Virginia barbecue legacy was still alive in Kansas City as late as the 1940s. From around 1930 to the late 1940s, there was a barbecue restaurant in Kansas City located at 606 East Thirty-First Street named Virginia Barbecue. The restaurant featured “Delicious Barbecue Ribs and Barbecue Meats.”66

POLITICAL BARBECUES

The political barbecue originated in Virginia. A grand barbecue was the one event that brought rural populations together like no other. Sometime in the eighteenth century, politicians from other regions, who saw how effective it was for gaining votes, adopted it as well. Charles Lanman described two types of Virginia barbecues: the social and the political. James Hammond Trumbull contrasted the development of the political caucus in the New England colonies with the political barbecue that first developed in Virginia.67 Playwright Robert Munford satirized Virginia’s political barbecues in his comedic play The Candidates in 1770.

Although some may overlook the importance of barbecue in the history of American politics, America’s founders didn’t overlook it. When Virginian George Washington laid the cornerstone of the Capitol in 1793, cooks barbecued a five-hundred-pound ox as part of the celebration. Moreover, just as Virginians had been doing for almost two hundred years before, there was much celebratory gunfire.68 Another testimony to the importance and influence of Virginia’s political barbecues exists in the “Barbecue Trees.” In 1903, the Washington Times reported:

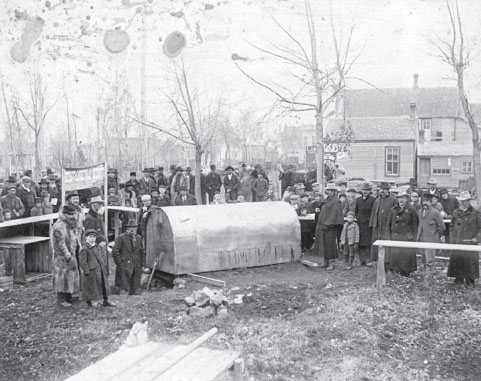

One of the earliest known covered barbecue pits. It was used to cook barbecue at a Republican campaign rally for President McKinley in Minnesota, 1896. Cottonwood County Historical Society.

South of the Washington Elm are the Barbecue Trees planted during Jackson’s Administration by James Maher, a Jolly Irishman who owed his appointment as superintendent of the Capitol Grounds to the President’s personal friendship. These trees are relics of two circular groves intended for barbecue celebrations one for Democrats the other for Whigs.69

In 1874, the government commissioned Frederick Law Olmsted to oversee a renovation of the Capitol grounds. He commented on the existing vegetation:

South of the “Washington Elm,” adjoining the East Court of the Capitol, there were a dozen long-stemmed trees, relics of two circular plantations introduced in the midst of Foy’s largest “grassplats,” by Maher, for “barbecue groves,” one probably intended for Democrat, the other for Whig jollifications.70

Maher planted the Barbecue Trees on the Capitol’s East Grounds. They were “relatively fast maturing trees, closely planted and [by 1874] were not effectively thinned or pruned. About forty years after their planting the larger number of those remaining alive were found to be feeble, top heavy, and ill grown.”71 The poor condition of the trees was probably due to neglect during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Sadly, Olmsted demolished the groves in the 1870s along with much of the rest of the Capitol grounds as his renovation work progressed. Incidentally, in addition to ordering the planting of the Barbecue Trees, Andrew Jackson is the first president recorded to host a barbecue at the White House, which occurred on Independence Day in 1829.72 Although there are claims that Jefferson was the first, there are no primary records to support them.

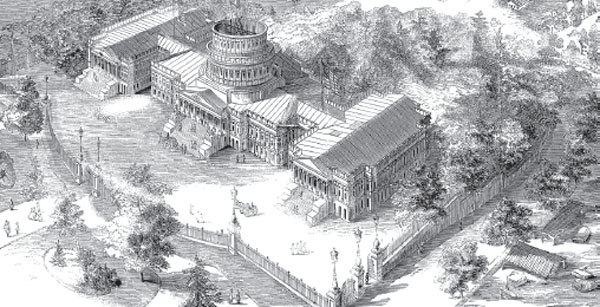

The “Barbecue Trees” are depicted in this 1861 pencil drawing of the U.S. Capitol as two groves in the lower left. From Harper’s Weekly (July 27, 1861). Reprinted with permission of Applewood Books, Carlisle, MA, 01741.

VIRGINIA BARBECUE AND THE SLAVE TRADE

Before the Civil War, Virginia played a leading role in the domestic slave trade, exporting far more slaves than any other state. Lorenzo Ivy was a slave who lived in Danville, Virginia. As an old man in his eighties, he recalled how slave traders would bring slaves from Virginia bound in chains, walking two by two in lines as far as the eye could see, as they were loaded into trains. He remarked, “Truly, son, de haf has never been tol’.”73

Karl Bernhard wrote in 1828 of the slave “nurseries” that existed in Virginia from which the Deep South was supplied with slaves.74 In 1859, a Texas newspaper reported, “An almost endless outgoing of slaves from Virginia to the South has continued for more than two weeks past”75 Between the years 1800 and 1809 alone, it is conservatively estimated that sixty-six thousand slaves were traded between states, of which forty-one thousand came from Virginia.76

Because most barbecue cooks in antebellum Virginia were African Americans, the enslaved people sent from Virginia throughout the South played a major role in spreading Virginia’s barbecue. This fact helps explain why the Virginia barbecuing technique and the Virginia barbecue baste of butter, salt, peppers and vinegar were used all over the South.

A VIRGINIA BARBECUE

Of the genus barbecue, as it exists at the present time, we believe there are only two varieties known to the people of Virginia, and these may be denominated as social and political. The social barbecue is sometimes given at the expense of a single individual, but more commonly by a party of gentleman, who desire to gratify their friends and neighbors by a social entertainment. At times, the ceremony of issuing written invitations is attended to; but, generally speaking, it is understood that all the yeomanry of the immediate neighborhood, with their wives and children, will be heartily welcomed, and a spirit of perfect equality invariably prevails. The spot ordinarily selected for the meeting is an oaken grove in some pleasant vale, and the first movement is to dispatch to the selected place a crowd of faithful Negroes, for the purpose of making all the necessary arrangements.

If the barbecue is given at the expense of half a dozen gentlemen, you may safely calculate that at least thirty servants will be employed in bringing together the good things. Those belonging to one of the entertainers will probably make their appearance on the ground with a wagon load of fine young pigs: others will bring two or three lambs, others some fine old whisky and a supply of wine, others the necessary tablecloths, plates, knives, and forks, others an abundance of bread, and others will make their appearance in the capacity of musicians. When the necessaries are thus collected, the servants all join hands and proceed with their important duties.

Charles Lanman, Haw-Ho-Noo: Or,

Records of a Tourist (1850)

VIRGINIA COOKBOOKS AND SOUTHERN BARBECUE

Virginia cookery was very influential in the 1700s and 1800s.77 Mary Randolph’s cookbook The Virginia Housewife was particularly popular and influential. The Improved Housewife, written by “A Married Lady” and published in 1844, is a witness to that fact. That book includes Mary Randolph’s barbecued pork recipe almost word for word and describes it as no longer merely a Virginian dish but rather “a Southern Dish.”78 Randolph’s influence also exists in foods served with barbecue. For example, in 1850, a writer described “southern barbecues,” which, at that time, often featured another Mary Randolph recipe: turkey with oyster sauce.79 Another example of Virginia’s influence on southern cookery exists in the oldest American cookbook written by an African American. The author, Mrs. Malinda Russell, was born in Tennessee to a family originally from Virginia. She published her cookbook in 1866. Mrs. Russell was taught to cook by a woman from Virginia named Fanny Steward. As a result, the Tennessean Mrs. Russell explained that she cooked “after the plan of The Virginia Housewife.”80

THE DECLINE OF GRAND BARBECUES

One of the earliest contributors to the decline of big barbecues in Virginia was religious revivals. During Virginia’s Great Awakening in the 1740s, preachers railed against the customs practiced at Virginia barbecues such as cockfighting, gambling, drinking and horseracing.81 In 1844, Dr. James Jones described the people of Nottoway, Virginia, before he helped found the Presbyterian Church there in 1825: “The county was irreligious throughout its length and breadth. Periodical jockey club meetings, reveling, balls, parties, barbecues, card and drinking parties, with a host of other dissipations of the most grossly immoral tendencies, obtained everywhere; but after this reformation all this disappeared.”82

In 1858, an author commented on Virginia barbecues as “another of the institutions of Virginia,” writing:

We are well aware that there are many persons of the present day who lift up their hands in holy horror at the wickedness of their predecessors, in this article of barbecues. If they can make out, to our satisfaction, that the present generation is either better, or wiser, or more sober, we give up the point. But, until that can be done, we shall cling pertinaciously to the memory of those good old days. We are not ashamed to confess that some of the most pleasant hours of life have been spent at these old fashioned barbecues.83

Because Virginia barbecues were often rowdy events accompanied by rough sports and games, it is easy to see why evangelists and churches would encourage people to avoid them.

Other factors that contributed to the decline of barbecues in Virginia, and throughout the South, were the Civil War and Reconstruction. In 1876, a writer commented, “Pity if so good an institution [Virginia barbecues] has gone down, as we fear it has in its original simplicity, among the other wrecks of the war.”84 R.T.W. Duke Jr., of Albemarle, Virginia, wrote in his memoirs, “War and its damnable successor, ‘Reconstruction’ stopped Barbecues until about 1873 or 74.”85 In 1910, a writer observed, “The picturesqueness of the olden-time political meetings and the necessary barbecue passed away with the Civil War.”86 Although this was an exaggeration, it does reflect the fact that after the end of the Civil War, barbecue events occurred in much less frequency. For example, in 1907, while discussing the possibility of holding a Labor Day barbecue at the Virginia State Fairgrounds, the planners wanted “a huge barbecue, such as has not been seen in many a day.”87

By 1863, the people of Richmond, Virginia, were engaging in food riots and things would only get worse for Virginians in those days before they would get better.88 By all accounts, Virginia, which had been the main Civil War battleground, was in ruins at the close of the Civil War. The fighting resulted in the destruction of homes, towns, public records, libraries and plantations. Virginia had no civil government, and Confederate money was worthless. Farmers had little or no money, stock or seeds, and there was no way to secure credit. Before the war, Virginia’s railways were among the finest in the world. After it, they were in ruins.89

Civil War destruction of the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad depot, 1865. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-cwpb-02700.

The residents of “Military District Number 1”—the federal designation for much of Virginia during its Reconstruction era—were in no mood to hold barbecues, even if they could have afforded them. In 1865, a writer observed, “It is now some years since the people of Virginia have participated in a regular old fashioned 4th of July celebration…We shall have no volunteer reviews nor target shooting, but we have seen too much of the genuine article of war.”90

Destruction caused by the Civil War at Fredericksburg in 1862. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-35109.

The “Glorious Fourth” had always been a day for barbecues in Virginia, going back to the earliest times in the history of the United States. However, that wasn’t the case during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Even after the war ended, Virginians were not quick to resume the celebration of Independence Day. One writer noted:

When the war came there were no holidays for the masses; it was all fighting and no frolicking. After the first year there were few new or clean uniforms to parade in, and no powder and caps to spare for salutes which would kill nobody. Hostilities ended, the Confederate flag furled, Richmond people looked at the un-turfed graves in Oakwood and Hollywood and at the burnt district in their city, and at the Federal troops quartered in the suburbs, and could not all at once revive Fourth-of-July patriotism in their breasts.91

It took more than two decades after the Civil War ended for “the Fourth” to become the “Glorious Fourth” again in Virginia. In fact, the Richmond Dispatch took note that in 1886 in Richmond, Virginia, “the day was more generally observed than any Fourth since the war”:

But as nature and human industry covered the scars of war, and the great majority of the North and of the South buried their differences, the observance of the Fourth again became general here. At first no attention was paid to it. Few closed places of business. Now, it is the most generally observed holiday of the year, Christmas alone excepted.

In these times, as of old, the stars and stripes float from every flag staff and masthead; but the crowds which used to picnic near the city [a reference to barbecues] now take excursion trains and fly to Washington, to Old Point, to the White Sulphur, to Fredericksburg, to Petersburg—indeed anywhere to be out of Richmond. The colored troops, ever burning with patriotism and ever indifferent to the burning sun, have usually stayed at home and paraded and marched and picnicked.92

Times were difficult in Virginia during its Reconstruction years. The Panic of 1873 and the depression that followed further negatively affected Virginia’s economy. Things were so bad in parts of Virginia that many of the poor people in Alexandria had “not a stick of wood or a pint of meal.”93 The lack of jobs and money, as well as the scarcity of food and livestock decimated by war, all played a role in the decline of old Virginia barbecues. In 1884, a writer for the Washington Post wrote of the attendees at a Virginia barbecue, “To them a barbecue was a novelty. They had attended these gatherings when they were boys, and now as grown men had come once again to listen to the speeches and eat a barbecue dinner.”94

At the close of the Civil War, many newly freed African Americans left Virginia and took Virginia barbecue with them. In 1879, ten barbecue men, enslaved in Virginia until the end of the Civil War, made their way to Cincinnati. There, they had steady work cooking old Virginia barbecue. On one occasion, they barbecued two oxen and eight sheep. The barbecue “was a great success, and fully 5000 people partook” of the Virginia-style barbecue.95

Because most accomplished Virginia barbecue cooks of the nineteenth century were African Americans, one must consider the possible effect of prejudice and Jim Crow laws in the decline of Virginia barbecues. A possible example of this is the experience of the Gordonsville, Virginia chicken vendors.96

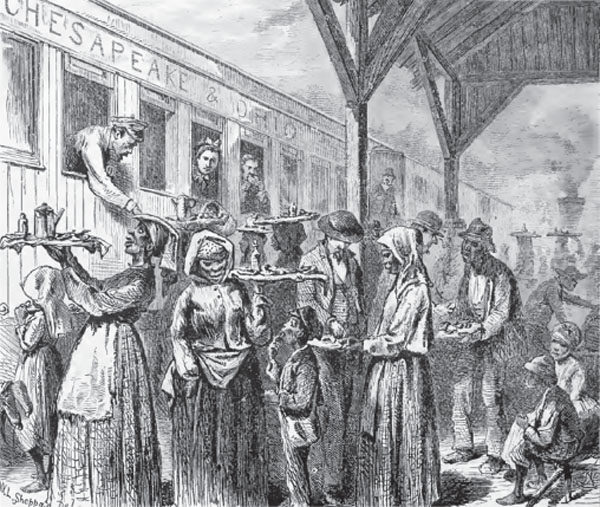

The Gordonsville chicken vendors—or “waiter carriers,” as they called themselves—became famous for their delicious Virginia-style fried chicken, sold to train passengers who stopped at the local junction. They started their business after the end of the Civil War, and it continued until the 1920s. Mothers and daughters spent their days cooking delicious foods such as biscuits, hoecakes, pies, coffee and fried chicken. The women would present the foods to train passengers using large platters they carried on their heads. Passengers often remained in the trains and this was a way to put the food within reach of the customers leaning out of the windows.

The chicken vendors’ business thrived for about five decades, with only a brief interruption caused by World War I. In the early twentieth century, the Gordonsville Town Council took notice of the women’s business and levied a tax on it. It wasn’t long before the tax was increased. Others took note of the thriving business and coveted it. After the end of World War I, a restaurant and hotel purchased exclusive rights to sell foods on the train station platform from which the chicken vendors had previously operated. Nevertheless, that didn’t stop the determined women. They simply sold their fried chicken from the side of the tracks opposite the station and did better business than the restaurant. Eventually, the restaurant closed, leaving the women again as the only food vendors for train passengers. It is estimated that they sold as much as one thousand chickens per week, fried using their secret recipe.

Gordonsville, Virginia’s “waiter carriers.” From The Great South by Edward King, 1875.

Eventually, another local restaurant acquired exclusive rights to sell food at the train station. This, along with high taxes and the fact that by the 1920s trains had added dining cars, eventually put the women out of business. It was a loss not only for the women and their families but also for Virginia. Many merchants in Gordonsville benefited from the women’s business—from the poultry merchants to the wrapping paper sellers; the vendor who sold the lard, salt, pepper and flour; and the town of Gordonsville itself, which received taxes from the women’s endeavors. All were a little poorer. Highlighting the loss is the fact that before the waiter carriers went out of business, Gordonsville was a chief supplier of chicken in the region. In 1920, the planners of a Charlottesville barbecue stated that they had “secured a special option on the chicken market in Gordonsville.”97 When the waiter carriers closed down, the lucrative Gordonsville chicken market closed with them.

The Town of Gordonsville, Virginia, remembers the waiter carriers today by holding an annual fried chicken festival in their honor. Author’s collection.

Virginia lawmakers didn’t make it easy on the famous Gordonsville chicken vendors. In fact, one could make the case that they were determined to close them down. It’s possible that Virginia barbecue cooks of the same era experienced similar difficulties.

At the turn of the twentieth century, even though Virginia had endured war, the turmoil of Reconstruction and the injustices of Jim Crow, Virginians, on occasion, were still holding grand Virginia barbecues. However, World War I and Prohibition would deal another blow to them. Duke Jr. commented about the “iniquitous, hypocritical, tyrannical & fanatical Legislation known as the 18th Amendment” and complained that “a Barbecue without something to drink was…a d-mn dreary place.”98

The death of the generation that was most expert at cooking Virginia barbecue also played a role in its decline, just as was predicted by Duke Jr.99 It is no coincidence that the loss of so many accomplished Virginia barbecue cooks of Caesar Young’s generation coincided with fewer mentions of Virginia barbecue in literature. For example, after the authors of the cookbook America Cooks wrote of Virginians in 1940, “Their favorite picnic is a barbecue,” there is a noticeable reduction in the publicity given to Virginia barbecues.100 In 1951, a Pennsylvania restaurant was bragging about its “tangy Virginia barbecue,” and an Arizona restaurant was advertising its James River pork barbecue with “[t]hat Fine, Old Virginia Barbecue Flavor.”101 However, as the 1950s ended, there were fewer and fewer advertisements for Virginia barbecue in other states. This did not go without notice from Virginians. In 1978, a columnist for the Richmond Times Dispatch noticed an increase in the number of barbecue restaurants opening in Richmond that served North Carolina–style barbecue. She commented that North Carolina–style barbecue had “not only crossed the state line, but kidnapped the market as well.”102

Perhaps another clue to the causes of the decline of grand Virginia barbecues exists in the story of the Brunswick stew master George Rogers. Rogers began cooking Virginia Brunswick stew in Halifax County around the year 1910. For decades in and around the Jamestown, Virginia area, he simmered, stirred and served Virginia Brunswick stew outdoors in large copper pots. When a reporter asked his son, Charles, if he was going to assume his father’s role, he replied that there is “too much work involved.”103

Often, fathers passed the art of barbecuing to their sons. Cooking barbecue and Brunswick stew for large events requires a tremendous amount of very hard work. Because of that, just like George Rogers’s son, young people sought other opportunities and pursuits. For example, John Dabney’s daughters became schoolteachers in Richmond. One of his sons became a professional baseball player, and another became a musician, writer and the founding editor of two Cincinnati newspapers.104

URBANIZATION AND BARBECUES

Urbanization took its toll in Virginia just as it did in other parts of the South. Thomas Jefferson wrote that in his day, Virginia towns were “more properly our villages or hamlets.”105 By the end of the eighteenth century, all cities in Virginia were still no more than small market towns compared to northern cities such as Philadelphia, New York and Boston.106 The populations of Richmond, Norfolk, Petersburg and Alexandria wouldn’t reach at least thirty thousand each until about 1860. It wouldn’t be until 1950 that the federal census would record for the first time that more Virginians were living in cities and towns than in rural communities.107

Moreover, as urbanization spread, the old Virginia barbecues were set aside in favor of other amusements. In 1891, a columnist wrote, “Railroads have almost revolutionized the Fourth of July.” He went on to explain how “country folks rush to the towns and the city folks dash to the country. Thus have excursion rates underdone the old-time ‘celebrations.’” In 1872, one writer observed that barbecues in the South were more common “before the late war than now.”108 In 1893, the American Historical Association noted, “The barbecue feast was a much more popular observance among the people in colonial times than at present,” and in 1899, another commented that barbecuing in the South “is now a lost art.” In the times before the Civil War, Chatham, Virginia, was famous for big barbecues. However, when people there hosted an “old-fashioned” Virginia barbecue in 1905 to welcome dignitaries, the novel event reminded attendees of the legendary barbecues that they had only heard of from their fathers.109

As far back as 1860, in an article in De Bow’s Review entitled “Country Life,” the author complained about how life had changed over the previous forty years, writing, “The pursuits and amusements of our parents are not our pursuits and amusements.” Offering a reason for the change, the author explained that it “consists in the country having become more and more dependent on the towns.” As a result, “The private social festive board is rarely spread; the barbecue, with its music and dance, is obsolete and almost forgotten.”110 Although such claims were, to an extent, exaggerations, they do reflect the impact of urbanization and the Civil War on southern barbecue.

In 1887, a columnist for the Louisville Courier-Journal declared, “The day of the barbecue in campaigns is over.” The reason for the decline, cited by the author, was “[t]he development of the national character.”111 By the turn of the twentieth century, political barbecues in Virginia were also on the way out. In 1910, a newspaper columnist asked, “[Are we] never again to have an old time political barbecue in Virginia?”112 As more and more people moved away from rural areas to cities and towns, fewer and fewer “old Virginia” political barbecues were held. Although urbanization didn’t end political barbecues in Virginia, they did become less frequent.

Author, food editor and journalist Raymond Sokolov observed that the preservation of authentic regional cooking requires thriving rural communities.113 In the twentieth century, Virginia’s barbecued meats moved from mostly “rural entertainments” to urban and city stands and restaurants. This resulted in changes to Virginia barbecue.

By 1941, Mechanicsville, Virginia, had transitioned from a very rural community filled with farm wagons and stables to a region filled with gasoline stations and barbecue stands.114 As Virginia’s barbecue made that transition, some of it lost its uniqueness. However, that’s true of barbecue all over the South, where the same transition occurred. A clear lack of barbecue diversity from region to region exists today. Just take a casual look through barbecue recipes posted on the Internet and in cookbooks. Beginning in about the 1950s, newspapers and magazines generously shared identical barbecue recipes all over the country. Barbecue cookbooks became popular, and national brands of bottled barbecue sauces were on shelves in every supermarket. These developments have blurred and, in some cases, erased the lines between many regional barbecue styles. This brings us to the fact that you can find barbecue in Virginia and you can find Virginia barbecue in Virginia. Although there are restaurants that sell Texas-style brisket and North Carolina–style pork, you can still find restaurants that proudly serve authentic Virginia-style barbecue. Alhough time has changed barbecue traditions in Virginia, in spite of what some barbecue “experts” might say, it hasn’t erased them.

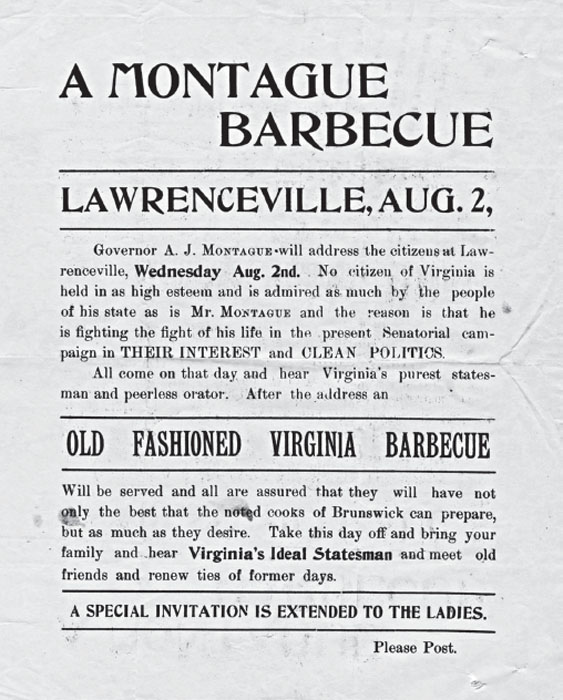

A flyer for an old-fashioned Virginia barbecue hosted by Governor Montague, 1905. Library of Virginia.

The only unbroken line of southern barbecue history begins in Virginia. Barbecuing in the Indian manner became barbecuing in the Virginian manner. As settlers from Virginia spread farther south and west, barbecuing in the Virginian manner spread with them and gave birth to barbecuing in the southern manner. At one time, what we call today “southern barbecue” only existed in the cultural hearth of the Tidewater region of colonial Virginia.115 However, Virginia’s barbecue monopoly didn’t last long. From its beginnings among Virginia’s “Chesapeake Creoles,” Virginia’s way of cooking barbecue spread throughout the South to become an enduring and cherished tradition for an entire region of the United States.116 Indeed, Virginia’s barbecue history and traditions have earned the Old Dominion yet another nickname: the “Mother of Southern Barbecue.”

Today, the number of barbecue restaurants and vendors who celebrate Virginia’s barbecue history by proudly serving authentic and delicious Virginia-style barbecue is growing. In April 2016, the Virginia General Assembly reaffirmed a long-held Virginia barbecue tradition by unanimously passing House Joint Resolution No. 169 designating May through October, in 2016 and in each succeeding year, as Virginia’s Barbecue Season. The proclamation sends a message that Virginians are still proud of their rich barbecue traditions and will continue to preserve them for future generations.