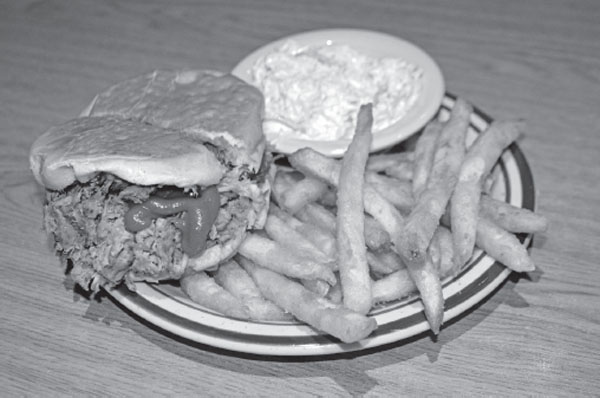

Pork barbecue sandwich topped with Virginia peanut barbecue sauce at Benny’s Barbecue in Richmond, Virginia.

CHAPTER 8

AUTHENTIC VIRGINIA BARBECUE RECIPES

The barbecue is one of our old Virginia institutions, which dispenses with form, ceremony and display. A plenty to eat, well cooked, and a plenty to drink, well mixed, with toasts and speeches, constitute the entertainment. This social gathering is held in the open air, near a spring and at a well shaded spot.

–Richmond Whig, “Barbecues,” July 20, 1869

Barbecue cooks have always had their secrets. For hundreds of years, most barbecue cooks in Virginia were enslaved African Americans. As a result, they couldn’t record their recipes in written form, so they passed them on by word of mouth or chose not to share them at all. Although some accounts mention the vinegar, butter, salt and peppers, writers didn’t often reveal many of the other secret spices and herbs in the sauce. Compounding the problem of discovering Virginia barbecue recipes is the fact that most Virginia barbecue cooks today also cherish their secrets. In fact, the secret nature of several Virginia barbecue recipes that I am privy to prevents me from publishing them in this book. For those reasons, and others, published research into Virginia barbecue recipes is and probably always will be incomplete. Even so, observation, experimentation and a diligent study of old diaries, books, magazines and newspapers can reveal many of the finer points of genuine Virginia barbecue recipes from as far back as the seventeenth century.

As new ingredients became available and as Virginians’ prosperity grew, so did the variations they used in their barbecue recipes. In colonial and federal times, more prosperous Virginians used relatively expensive ingredients compared to Virginians who were less well to do. At around the turn of the twentieth century, when food manufacturers realized that sugar makes just about everything taste better, Americans developed a sweet tooth, and sugar consumption soared. Consequently, barbecue sauce manufacturers all over the country increased the amount of sugar in their recipes. Virginia barbecue was no exception. Today, Virginia barbecue sauces range from thin and vinegary to thick and sweet, often including “all sorts of spices.”1 They reflect both the simple Virginia pepper vinegar sauces and those that meet the modern expectations of kick, sparkle, spice, zest and zing.2

VIRGINIA BARBECUE SAUCES THROUGH THE CENTURIES

Virginia’s vinegar-based sauce tradition is older than North Carolina’s. Although North Carolina’s vinegar-based sauces are delicious, Virginia’s vinegar-based sauces are special, too. Nineteenth-century Virginia barbecue sauces contained “vinegar, peppers, and other spicy condiments.”3 The “other spicy condiments” could include herbs, spices, mustard, Worcestershire sauce and even horseradish.

Pork barbecue sandwich topped with Virginia peanut barbecue sauce at Benny’s Barbecue in Richmond, Virginia.

Using a patented design that creates an incredibly “stable, uniform, and efficient cooking environment,” 270 Smokers manufactures high-quality barbecue cookers in Virginia. Stephanie and Terry West.

Oils traditionally used in Virginia barbecue sauce recipes include butter, lard and bacon fat. Modern substitutions include canola oil, soybean oil and peanut oil. Virginians have used such sweeteners as sugar, molasses, honey and stewed or jellied fruits for hundreds of years. This is illustrated in a description of a Virginia barbecue from 1836 where the author told of barbecued meats served with “all kinds of preserves.”4

According to eyewitnesses, the oldest Virginia barbecue sauce is a combination of water or vinegar, butter or lard, salt and red pepper. Some recipes used all of the ingredients. Some used only a few. Sometimes cooks added additional ingredients, such as black pepper, mustard, sugar and herbs. Virginians derived the basic recipe from English recipes from the sixteenth-century published in cookbooks that colonists brought with them from England. For example, in a 1675 recipe entitled “To Broyl a Leg of Pork,” we find a sauce recipe consisting of butter, vinegar, mustard and sugar.5 Those old English recipes for grilling and carbonadoing meats are the ancestors of the original Virginia barbecue sauce that became the foundation for barbecue sauces all over the South.

I have been very happy since my arrival in Virginia, I am continually at Balls & Barbecues (the latter I don’t suppose you know what I mean) I will try to describe it to you, it’s a shoat & sometimes a Lamb or Mutton & indeed sometimes a Beef splitt into & stuck on spitts & then they have a large Hole dugg in the ground where they have a number of Coals made of the Bark of Trees, put in this Hole, & then they lay the Meat over that within about six inches of the Coals, & then they Keep basting it with Butter & Salt and Water & turning it every now and then, untill its done, we then dine under a large shady Tree or an harbour made of green bushes, under which we have benches & seats to sit on when we dine sumptuously, all this is in an old field, where we have a mile Race Ground & every Horse on the Field runs, two & two together, by that means we have a deal of diversion, and in the Evening we retire to some Gentle’s House & dance awhile after supper, & then retire to Bed, all stay at the House all night (it’s not like in your Country) for every Gentleman here has ten or fifteen Beds which is aplenty for the Ladies & the Men ruff’s it, in this manner we spend our time once a fortnight & at other times we have regular Balls as you have in England.

Lawrence Butler, “Letters from Lawrence Butler, of Westmoreland

County, Virginia, to Mrs. Anna F. Cradock, Cumley House, near

Harborough, Leicestershire, England” (1784)

Mary Randolph’s cookbook The Virginia Housewife sheds much light on Virginia barbecue. Randolph was born in Goochland County, Virginia, in 1762. She was kin to Thomas Jefferson and Mary Lee Fitzhugh. Randolph’s cookbook was, according to Karen Hess, the most influential cookbook of the nineteenth century. Randolph died in 1828.

A versatile sauce shared by Randolph is Virginia pepper vinegar. The recipe calls for simmering Virginia chili peppers (cayenne peppers, bird peppers or fish peppers) in vinegar—after which the sauce is to be strained to remove the remains of the peppers. Pepper vinegar was used as an ingredient in ketchups and sauces. It was also used as a sauce on meats of all kinds, including barbecued meats. According to Randolph, its flavor is “greatly superior to black pepper,” which illustrates how Virginians often substituted chili peppers for black pepper.

Virginia-style barbecue sauces served at 1752 Barbecue in Woodstock, Virginia. Craig George.

Randolph’s “barbecue shote” was seasoned with garlic, pepper, salt, red wine, mushroom ketchup and browned sugar. Randolph’s mushroom ketchup contains mushrooms, salt, garlic and cloves. The “shote,” or young pig, was stuffed with minced meat seasoned with sweet herbs, mace, nutmeg, lemon peel, salt and pepper. “Sweet herbs” could be any combination of parsley, sage, thyme, savory, marjoram, spearmint, dill, fennel, tarragon, balm, basil, coriander, bay leaves, chervil and rosemary. In the 1800s, sage was “the universal flavoring” and “the seasoning par excellence for rich meats such as pork.” Virginians used mint mainly as a seasoning for peas, lamb, roast pork and in mint juleps.6 Therefore, any of the sweet herbs are appropriate for use in authentic Virginia barbecue recipes.

Mushroom ketchup was popular in Virginia barbecue recipes for a long time. However, by the late nineteenth century, many Virginians had replaced mushroom ketchup with Worcestershire sauce. By 1885, the Virginia Cookery-Book included several ketchup recipes but, unlike earlier Virginia cookbooks, no recipes for mushroom ketchup. Instead, there is a recipe for Worcestershire sauce. Interestingly, the Worcestershire sauce recipe calls for fresh tomatoes in the mix.7 Because old recipes for Worcestershire sauce often included mushroom ketchup and/or walnut ketchup as an ingredient, it turned out to be a good, easy-to-acquire substitute for both.8 For example, by 1913, one author gave the cook a choice of using either “a tablespoon of Worcestershire sauce or mushroom-ketchup.”9 A kitchen barbecue recipe from 1898 calls for a sauce made of ketchup, butter and sherry. The author of the recipe allows for Worcestershire sauce or mushroom ketchup as substitutes for the sherry.10 Apparently, Virginia’s influence on barbecue flavors includes not just vinegar and red pepper but also mushroom ketchup and Worcestershire sauce.

Virginia-barbecued whole hog in Louisa, Virginia. Bill Small.

Randolph’s method for roasting a pig is more like a traditional Virginia barbecuing method than is her kitchen barbecuing method. When roasting a pig, Randolph instructs us to baste it “at first” with salted water before switching later to rubbing it frequently with lard “wrapped in a piece of clean linen.” Of course, Virginia barbecue cooks had been basting barbecuing pigs with salt, water and lard using clean linen attached to mops for at least two hundred years before Randolph published her roast pig recipe.

Stuffing a pig with a mixture of minced meat, herbs and spices is a part of Randolph’s kitchen barbecue recipe. However, there are no records of Virginians using minced meat when barbecuing pork outside on a barbecue pit. Because Randolph’s kitchen barbecue recipe re-creates Virginia barbecue flavors in the kitchen, seasonings such as sweet herbs, lemon peel, lemon juice and spices such as mace, cloves and nutmeg can be used to season barbecue without using the minced meat as a carrier.

Randolph also shared a “white sauce for fowls” made with veal or fowl stock, mace, anchovies, celery, sweet herbs, lemon, pickled mushrooms, nutmeg, cream and black pepper. The sauce is an appropriate accompaniment for any kind of fowl, including chicken, no matter whether it was boiled, roasted or barbecued.

Marion Cabell Tyree’s 1879 cookbook Housekeeping in Old Virginia contains several barbecue recipes. Tyree, born in 1826, was Patrick Henry’s granddaughter. Her cookbook is a compilation of recipes shared by nearly 250 Virginian women in which is found “many names famous through the land.” The recipes in Tyree’s cookbook came from “the best housekeepers of Virginia.” In 1879, they represented the “garnered experience” of the previous one hundred years.11 Tyree died in 1912.

Tyree shared a “meat-flavoring” recipe that includes onions, red pepper pods, brown sugar, celery seed, ground mustard, turmeric, black pepper, salt and cider vinegar. Cooks included this sauce in many recipes for stews, gravies and barbecue.

Other barbecue recipes shared by Tyree call for walnut or tomato ketchup as an ingredient. She also shared a sauce that uses currant jelly as a sweetener. The ingredients in her various walnut ketchups include horseradish, mustard, garlic, shallots, allspice and ginger. One recipe calls for “any kind of spice you like.” Although we may not use walnut ketchup nowadays, we can use a combination of the flavors that were in it and still make a tasty and authentic Virginia barbecue sauce.

Tomato ketchup recipes in Tyree’s cookbook include various ingredients: “spices,” brown sugar, horseradish, mustard, ginger, cloves, celery seed and red pepper. Adding a combination of those ingredients to tomato ketchup can stand in for Tyree’s homemade ketchups for use in modern versions of Virginia barbecue sauces.

Mary Virginia Terhune’s two cookbooks are rich primary sources for old Virginia barbecue recipes. Terhune was born in Amelia County, Virginia, in 1830. She wrote several books under the penname Marion Harland. Like Mary Randolph, she also shared kitchen barbecue recipes. Terhune died in 1922.

By 1917, paprika was “used extensively” in the United States in sauce and pepper vinegar recipes. Terhune’s Virginia barbecue recipes reflect that fact. They include ingredients such as vinegar, butter, salad oil, salt, pepper, onion juice, mustard and paprika. Terhune’s recipe for barbecued rabbit calls for turning it often as it barbecues. The barbecued rabbit should be put in a dish with “pepper and salt and butter profusely” added before letting it rest for five minutes, after which you are instructed to “anoint” it with a mixture of butter, vinegar, mustard and minced parsley.12 Her kitchen barbecue recipe for barbecued ham calls for vinegar and sugar in the sauce.

The BBQ Jamboree is one of the largest barbecue competitions in the state of Virginia. It is an annual event that takes place in Fredericksburg, Virginia. Jeremy Bullock and James Sharon.

Lettice Bryan’s 1839 cookbook The Kentucky Housewife is a valuable resource for Virginia barbecue recipes. Lettice Bryan was the wife of a native-born Virginian named Edmund Bryan. Her father’s family has roots in Virginia from times long before Kentucky became a state in 1792. Many of Bryan’s recipes are much older than the nineteenth century, and as was the custom of her times, her parents’ and her husband’s families handed them down to her.13 For those reasons, as well as the fact that Kentucky received its barbecue tradition from Virginia, it is appropriate to use Bryan’s cookbook to shed light on old Virginia barbecue.14 The Virginia influence in Bryan’s barbecue recipes shines in her basting sauce of salt water and pepper and her use of stewed fruits in sauces served with the barbecue. Her barbecue recipes include an Indian barbecue recipe for venison hams, as well as a barbecue recipe used for both pork and beef.

Virginia red and Virginia mahogany sauces at Paulie’s Pig Out in Afton, Virginia. Author’s collection.

Bryan’s bread sauce recipe, recommended for barbecued pork and beef, calls for the optional ingredient of Madeira wine. Bryan’s use of Madeira wine demonstrates English influences. In the 1770s, a French translator described a Virginia barbecue as (roughly translated) “a barbarous amusement where they tenderize pork by beating pigs to death with sticks.” The author of the book, Englishman Andrew Burnaby, corrected the record, explaining, “In justice to the inhabitants of Virginia, I must beg leave to observe, that such a cruel and inhuman act was never, to my knowledge at least, practiced in that country. A Barbecue is nothing more than a porket killed in the usual way, stuffed with spices and all rich ingredients, and basted with Madeira wine.”15 Burnaby described English barbecue, not Virginia barbecue. Alexander Pope wrote, “hog barbecu’d” is “a hog roasted whole, stuffed with spice, and basted in Madeira wine.”16 Again, Pope, an English poet, is referring to an old English barbecue recipe. We also have the British author who, in 1771, wrote about English “barbicue” that was “thoroughly impregnated with Madeira.”17 Ward’s The Barbacue Feast, or, The Three Pigs of Peckham, Broil’d Under an Apple-Tree, published in 1707, describes English sailors cooking barbecue while basting it with Madeira wine. This stands in contrast to Virginia’s barbecue sauce of butter, vinegar, salt and peppers. Virginians rarely used wine in barbecue recipes. When they did, red wine was preferred.

Bryan’s pork and beef barbecue recipes exhibit a true Virginia style of barbecuing over “a bed of clear coals.” She exhorts the reader to “not barbecue it hastily” but rather let it “cook slowly for several hours.” Before barbecuing, rub the meat with salt, pepper and molasses; rest for a few hours; and wipe dry before barbecuing it. As it cooks, she advises that we turn it occasionally while basting it with the old Virginia mixture of salt water and pepper. Before serving the barbecue, she instructs us to squeeze “a little lemon juice” over it. To accompany the barbecue, Bryan recommends melted butter, wine, bread sauce, coleslaw, cucumbers and stewed fruit.

In 1839, barbecue sauce as we think of it today didn’t exist. It wasn’t until around 1871 that “barbecue sauce” was a product that could be purchased, and there are no recipes specifically for “barbecue sauce” in any cookbooks until around the 1870s. Before that time, people served whatever sauces they liked rather than something they called “barbecue sauce.” This practice started with the original barbecue sauce derived from carbonado recipes. It continued in Bryan’s sauce suggestions for her barbecued shoat. Her recipes for both barbecue shoat and roast pig call for bread sauce and fruit sauce made with stewed fruit served on the side. We can also see this practice in the 1825 Schuylkill, Pennsylvania barbecue where attendees enjoyed “a fine barbacue [sic] with spiced sauce” but not a “spiced barbecue sauce” as we would call it today.18 This implies that sauces served with roasted meats and barbecued meats were often the same. From colonial times, people referred to barbecued ox using the phrase “ox roasted whole.” Terhune defined barbecue as “to roast any animal whole, usually in the open air.”19 This association of roasted meat with barbecued meat implies that the recipes used with both were similar. See Randolph’s roast pig and barbecued shote recipes for other examples.

Virginians have served jellies and fruit syrups as a sauce or used them as ingredients in sauces for barbecued meats for centuries. As you will recall, the hosts of Thomas and Nancy Lincoln’s marriage celebration served peach syrup along with the barbecued sheep. From several accounts, we see that Virginians often served fruit syrups and jellies with mutton, venison, beef and pork, which, of course, introduced a sweet flavor to the barbecue. Although common today, it’s hard to say how widespread the practice of using fruit jelly as an ingredient in barbecue sauce was in the nineteenth century outside Virginia and Kentucky. In 1921, a Philadelphia newspaper printed a Virginia-style barbecue recipe that calls for currant jelly as an ingredient in the barbecue sauce. According to the author, such ingredients in barbecue sauce were “unusual.”20

Shenandoah Valley–style barbecue baste. Author’s collection.

Many Virginia barbecue recipes include mustard. In Virginia, mustard isn’t a base for barbecue sauce as it is in South Carolina. It’s one of the “spicy condiments” used as a flavoring in Virginia barbecue sauces. Accounts of John Marshall’s Buchanan’s Spring Barbecue Club tell us that the barbecue was “highly seasoned with mustard, cayenne pepper, and a slight flavoring of Worcester sauce.”21 English and German immigrants brought the practice of using mustard in sauces served with roasted meats to Virginia. Of course, the early English colonists used mustard, and it was very popular in sixteenthand seventeenth-century England.22

King’s Famous Barbecue of Petersburg, Virginia, serves delicious barbecue cooked “the Virginia Way.” Matt Keeler.

In addition to Englishmen, several Germans were among the first settlers to arrive with Captain Christopher Newport on his second voyage to the Virginia colony in 1608. Between 1714 and 1721, several larger groups of German settlers made their way to Virginia. By 1727, the German settlement, known as Germanna, reached from Spotsylvania County all the way to the Blue Ridge Mountains.23 Before the start of the Civil War, there were so many German immigrants in Richmond, Virginia, that one writer commented, “To judge from the conversation heard in the streets, one might be at a loss to ascertain whether German or English was the language of the country.”24 Therefore, it should be no surprise that they, too, had some influence on old Virginia barbecue flavors.

The oldest-known recipes for Virginia barbecued rabbit call for barbecuing it on a hurdle directly over coals, turning it frequently while basting it with and/or serving it with a mixture of butter, vinegar and mustard.25 In 1888, an eyewitness shared an account of Virginians barbecuing a rabbit. First, they gashed the carcass with a knife with strokes about one inch apart so that the sauce could penetrate the meat. The cooks were careful to make sure that none of the coals was smoking or smoldering because the dense smoke might “destroy the flavor,” which is a holdover from the seventeenth-century carbonado recipes. The barbecuing rabbit was basted with a sauce made of a combination of mustard, “all sorts of spices,” vinegar, pepper, salt and brandy, or whatever liquor is preferred to give it a “high flavor.” This baste was called “the seasoning.” The host served currant jelly with the barbecue on the side.26 As far back as at least the early 1800s, some also served rabbit barbecued the same way but with currant jelly or brown sugar added as an ingredient mixed into the sauce that they poured over the meat before serving it.27 Although this is an account of Virginia-style rabbit barbecue, the ingredients and barbecuing technique were used for other meats as well. The same is true of Virginia-style squirrel barbecue recipes.

Virginians have used some ingredients that many don’t usually associate with barbecue, including anchovies, shallots, maple syrup, peanuts and sassafras. Sassafras and shallots grow wild in Virginia, so it shouldn’t be surprising that they made it into Virginia barbecue from time to time. “For centuries,” Blue Ridge mountain men used to insert stalks of sassafras and other “yarbs” (herbs) into meat before barbecuing it.28 Incidentally, Kentucky frontiersmen used sassafras in burgoo, too.29

Virginia Red barbecue sauce at Ace Biscuit & Barbecue in Charlottesville, Virginia. Author’s collection.

The hardwoods traditionally used to cook Virginia barbecue include hickory and white oak. Other varieties of hardwoods used for barbecue include chestnut, apple and pecan. Virginia barbecue cooks were always careful to make sure that the fires in their pits had burned down to glowing embers with little or no visible smoke rising from them before putting meat on the pit. With Virginia barbecue, smoke and seasoning play a background role in the flavor of the meat.

Even though sassafras leaves and “yarbs” have been used to season Virginia barbecue, it is doubtful that cooks ever used sassafras wood to cook it. Both Cherokee Indians and white settlers avoided using sassafras wood as fuel probably due to its tendency to burst and “pop” out of the fire.30

Some of the recipes listed in Beverages and Sauces of Colonial Virginia no doubt made it to many a plank table erected beside a spring, including the recipe for “House of Burgess’s Mint Julep.” Because Virginians were fond of serving fruit-based sauces with barbecue, some probably served “Sauce for the Goose and Sauce for the Gander” with barbecue from time to time. The recipe calls for apples, butter and sugar to taste. Several sauces for wild game are in the book, including a sweet sauce for venison and a sauce that’s “good with all kinds of game” made with vinegar, lemon, orange peel, mace, cloves, cayenne, mustard, tarragon, laurel leaves, shallots, garlic and white wine.

The Barbeque Exchange in Gordonsville, Virginia, serves “slow cooked Virginia goodness” and has been named one of the top one hundred barbecue restaurants in the United States. Author’s collection.

“Newport’s Sauce for Game” is suspiciously similar to Mary Randolph’s “barbecue shote” sauce. It calls for port wine, mushroom ketchup, sugar, lemon juice, cayenne and salt. There are also white sauce recipes, a sauce made with bacon and various ketchup recipes, including a walnut ketchup recipe with cloves, nutmeg, vinegar, ginger, pepper, horseradish, shallots, port wine and anchovies. A “sauce for steaks” recipe includes vinegar, mustard, salt, pepper and lemon juice.31 All of those ingredients have been used in Virginia barbecue recipes from time to time.

In the late 1920s, President Hoover settled into his vacation house in Virginia on the headwaters of the Rapidan River known as his Summer White House, where he often enjoyed Virginia barbecue.32 By then, Virginia barbecue recipes were beginning to change with the times. Although the original Virginia barbecue sauce of vinegar, butter, salt and peppers was still in use—with additional ingredients such as tomato ketchup, sugar and Worcestershire sauce—Virginians, as they always had, began to incorporate modern customs and ingredients, such as barbecue sauce on the side, paprika and even chili powder.

A Virginia barbecue sauce recipe first published in the 1930s combines Randolph’s colonial-era Virginia pepper vinegar recipe and Tyree’s 1879 meat flavoring recipe. This sauce calls for ingredients such as one hundred long, hot red peppers; vinegar; ground onions; dry mustard; black pepper; Worcestershire sauce; and celery salt.33

Allman’s Bar-B-Q of Fredericksburg, Virginia, has been serving its delicious central Virginia–style barbecue sauce since 1954. Author’s collection.

The Richmond Times Dispatch columnist Emma Speed Sampson shared a barbecue sauce recipe in 1935 that was apparently quite popular in Virginia at the time. The recipe includes onion, butter, vinegar, brown sugar, ketchup, Worcestershire sauce, mustard and celery. Sampson explained that people modified the basic recipe to their personal tastes. Some people liked more sugar in the recipe, some more Worcestershire and some people added garlic.34 In the 1930s, the Virginia barbecued rabbit recipe was still popular. The Ginter Park Women’s Club of Richmond, Virginia, published a recipe for it that is very similar to the nineteenth-century recipe, calling for soaking the rabbit in salted water and serving it with a sauce made of vinegar, mustard, butter and “currant or any acid jelly.”35

In Virginia Cookery Past and Present, published in 1957, there are several delicious Virginia barbecue recipes.36 One sauce recipe calls for dry mustard, sugar, black pepper, celery seed, salt, red pepper and vinegar. The mop recipe given for barbecued lamb calls for butter, vinegar, Worcestershire sauce, red pepper and the optional ingredient of garlic. The recipe for barbecued chicken calls for salt, pepper, paprika, sugar, chopped onion, tomato puree or ketchup, “fat,” Worcestershire sauce and vinegar and/or lemon juice. The recipe for barbecued pheasant calls for tomato, onion, lemon, sage, mustard, salt, cayenne, sugar, garlic, pepper, butter and rosemary. The recipe included for barbecued rabbit is pretty much the same as the nineteenth-century recipes, calling for vinegar, salt, butter, mustard and red pepper, with the more modern addition of Worcestershire sauce. There is no mention of currant jelly. The recipe “Barbecue Filling for Buns” is more properly a Virginia-style barbecue hash recipe than strictly a barbecue recipe. It, too, includes the typical Virginia ingredients but with the addition of chili powder.

Chicken being barbecued Virginia style at Tabernacle United Methodist Church in Spotsylvania County, Virginia. Author’s collection.

In keeping with the Virginian “spiced” barbecue sauce theme, a recipe shared in A Taste of Virginia History: A Guide to Historic Eateries and Their Recipes includes ketchup, brown sugar and mustard, with spices such as cloves and allspice. Interestingly, the recipe does not call for vinegar.37 The author of Eat & Explore Virginia shared a recipe that includes Mary Randolph’s “sweet herbs” such as basil, oregano and thyme along with tomato ketchup and wine vinegar.38 A Virginia recipe for barbecued squirrel shared by the Patawomeck Indians of Virginia includes onions, brown sugar, Worcestershire, hot sauce, lemon juice, mustard and blackberry wine.39 A Fredericksburg-region barbecue sauce shared in 1985 includes tomato ketchup, Worcestershire sauce, sugar or honey, vinegar, salt and pepper.40

The Women’s Society of Christian Service of Virginia published the delightful cookbook Kitchens by the Sea in 1962. A kitchen barbecue recipe in it includes onions, celery, green pepper, vinegar, tomato sauce, garlic, dry mustard and brown sugar. Other barbecue sauce recipes in the book include vinegar, Worcestershire sauce, molasses, lemon juice, ketchup, mustard, celery, brown sugar and “hot pepper.”41

Early morning pork butts seasoned with a Virginia-style rub ready for the barbecue pit. Author’s collection.

Virginia is also a producer of maple sugar, so it should be no surprise that a Virginia barbecue sauce recipe published in 1975 includes it, as well as other ingredients such as mustard, celery seed, black pepper and tarragon vinegar.42 A Virginia-style barbecue sauce recipe for beef published in 1976 is made of beef broth, tomato ketchup, garlic, mushrooms, onion, green pepper, hot sauce, mustard and black pepper.43 The mushrooms are apparently an homage to Randolph’s mushroom ketchup. In the popular cookbook Virginia Hospitality, first published in 1975, are several Virginia barbecue recipes. One recipe calls for bacon drippings, and dry sherry is required in another.44

There are several commercial Virginia-style barbecue sauces on the market. One is “an old Virginia recipe with roots in Tidewater” and has been unchanged since it first appeared on shelves in the 1950s.45 For decades, people as far away as Boston have been enjoying it on barbecue and roast beef sandwiches. It is a Virginia brown sauce with a delightful tang typical of Southside barbecue sauces. There is a commercial central Virginia/Piedmont-style sauce that was “extrapolated from an old slave recipe.” It is slightly sweet and spiced.46 There are some Northern Virginia–style commercial barbecue sauces available too.

Not only does Virginia have unique barbecue sauces, but Virginians also have their unique ways of cooking barbecue. Tyree shared a recipe for barbecued ribs. The recipe states that one should “always par-boil ribs” before broiling them seasoned with salt and pepper. By 1947, barbecued spareribs had become a staple in Virginia, whether boiled or not.47 A 1931 Virginia barbecued rabbit recipe calls for soaking the rabbit in a brine before searing it in a frying pan and parboiling it before barbecuing it, at which time it should be basted with a mixture of vinegar, tomato ketchup, Worcestershire sauce, salt, mustard, red pepper and a little water.48

Nowadays, barbecue cooks turn up their noses to the idea of parboiling meat, calling it “faux-que.” However, there are good reasons for boiling some meats before barbecuing them. The modern taboo against boiling meat before barbecuing it is a reflection of modern times, when we have easy access to high-quality cuts of meat. People weren’t always so fortunate in earlier centuries. In 1909, an old-school barbecue expert explained, “Tough meat is previously parboiled in large pots.”49 Before the times of ubiquitous refrigeration, people would barbecue whatever meat they could get. In those times, you couldn’t run down to the local grocery store and pick up an eight-pound pork shoulder cut from a hog that was specially bred, fed and raised to produce a consistent quality of meat. The lower the quality of the meat, the higher the chances were that it could benefit from boiling. In addition, slaughtering older animals for barbecues was a frequent occurrence. That means that the meat was stringier and tougher than the meat of young animals, and boiling it in a seasoned broth before barbecuing it made a lot of sense because boiling tenderizes meat.

There used to be a vacant lot in Staunton, Virginia, that was used to impound stray cattle called “Stuart’s meadow.” In 1840, the Whigs couldn’t pass up the opportunity to eat free beef. They “slaughtered many” of the stray cattle there and threw a barbecue.50 One has to wonder how tough the meat was from those stray animals and if boiling played a part in its preparation.

Many southern states, in addition to Virginia, have a long tradition of boiling meats before barbecuing them, and it is as much a part of the southern barbecue tradition as hickory wood and vinegar sauces.51 In 1971, boiling meat before barbecuing it was a popular practice among barbecue cooks in Atlanta, Georgia.52 Boiling meat before barbecuing it was commonplace in some Texas circles, and it still occurs, though many “won’t admit it.”53 The famous Texas barbecue cook Walter Jetton shared his “Texas Beef Barbecue” recipe in 1965 that calls for boiling a beef brisket in a Dutch oven before finishing it on the grill.54 All-encompassing declarations that you should never boil meat before barbecuing it are not in keeping with “old school” southern barbecue tradition. However, with the high-quality meat available today, there is little need to boil it before barbecuing it. In Virginia, boiling meat before barbecuing it is the exception, not the rule. I am not aware of any restaurants or vendors today that serve the parboiled version of Virginia barbecue.

Beef and lamb boiling at a Kentucky barbecue, circa 1940. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-fsa-8a42934.

Virginia-style barbecued pork on the barbecue pit at 1752 Barbecue in Woodstock, Virginia. Craig George.

Virginians have been wrapping meat while barbecuing it for centuries. The account of the wedding of Abraham Lincoln’s parents tells of how the cook covered the meat with leaves as it barbecued. John Clayton recorded as far back as 1687 how Virginia Indians wrapped venison in leaves “barbecuting” it in embers.55 Several hundred years before wrapping barbecue while cooking it became the “Texas crutch,” the practice was first the Virginia crutch, apparently.56

In 1883, a newspaper columnist extolled Virginia barbecue, writing, “The old Virginia barbacued [sic] meats are of world-wide fame, and the system is simply to cook on or near coals in the open air.”57 Barbecuing directly on coals is a Virginia technique first practiced by Virginia’s Indians and continued by Virginia barbecue cooks in colonial and federal times.

Virginia barbecue cooks nowadays prefer to serve barbecued beef, pork and chicken. Brisket is relatively new in Virginia and is not a traditional beef cut used for barbecue in the state. Barbecued beef ribs, chuck, round and sirloin are Virginia’s barbecued beef specialties. Virginia’s barbecued pork specialties include pork shanks, shoulder cuts, ribs and pork belly. The Barbeque Exchange in Gordonsville serves a mouth-watering Virginia-style barbecued pork belly that is delicious.

Of course, there is also the famous Shenandoah-style barbecued chicken. Silas David Shirkey (1910–1990) is famous in the Shenandoah Valley for his Virginia barbecued chicken. Shirkey began barbecuing chicken for fundraisers back in the 1940s in and around the Harrisonburg, Virginia area. His famous Virginia-style barbecue sauce—which includes vinegar, pepper, herbs, garlic and lemon juice—is tangy and addictive.58 Nowadays, barbecue cooks all over the state use variations of Shirkey’s basic recipe when they are “flippin’ chicken” (as we say in Virginia) over open pits.

I will never forget the barbecued beef chuck sandwiches that a local barbecue restaurant used to serve in my hometown years ago. The delicious and tender, chopped beef sandwiches were tangy with a hint of sweetness from the sauce and topped with coleslaw. In addition to barbecuing beef until it is tender enough to pull, Virginians have a tradition of barbecuing beef to a medium-rare and medium level of doneness. A 1901 account of a barbecue in Westmoreland, Virginia, tells of a barbecued ox that “was done to a turn. From this savory lump one could have served at once, steak rare or well-done, the rib roast, sirloin or porterhouse.”59 You can still find Virginia-style barbecued beef served medium-rare to medium in Virginia barbecue restaurants today. King’s Famous Barbecue in Petersburg has served pork and beef since it opened in 1946. One of its specialties is a delicious Virginia-style barbecued beef made from top butt sirloin.

A VIRGINIA BARBECUE

The place was a Virginia picnic resort in the heart of the woods, not many miles from Washington. It was particularly fitted for a barbecue, being furnished with a pavilion and a bountiful spring, while through the hollow ran a little stream, a tributary of the Potomac. The woods around were clothed in all the gorgeous dress of autumn. Early in the day the farmers began to arrive, bringing their wives and families in commodious farm wagons, and picketing their horses in the grove. To them a barbecue was not a novelty. They had attended these gatherings when they were boys and now as grown men had come once again to listen to the speeches and eat a barbecue dinner.

The night previous to the barbecue an ox weighing 600 pounds had been slaughtered and dressed. A trench about three feet deep, three feet wide, and six feet long had been dug in the ground, and an iron grating laid in it a few inches from the bottom. Upon this grating an immense fire of logs had been built. The carcass of the ox had been “spitted” with a long pole, which was supported on tripods at each end of the trench. At one end of the spit was a crank, and this was turned steadily by relays of men during the entire night, the fire being kept at as near a uniform heat as possible.

From twelve to fifteen hours are required to roast an ox in this manner. The seasoning of pepper and salt is mixed in a bucket and applied liberally while the crank is being turned. The flesh soon assumes a rich brown, and the smell is a most savory one. Great care must [be] taken not to cook the beef too quickly. Generally a man who has experience in barbecues is engaged specially for the occasion, and he must give the cooking his entire attention if he wishes to make his work satisfactory. When the roasting is completed the fire is allowed to die out, but the ox remains upon the spit, the admiration of a large crowd, until it is time to cut up the meat for dinner.

In the same way three or four sheep are roasted whole. But simply bread and meat will do for a barbecue dinner. The immense iron pot…is filled to the brim with sweet potatoes. A barrel and a half of these are consumed at the barbecue which is now being described. The coffee, too, is made on a large scale. Ten or fifteen pounds are wrapped up in a cloth and thrown into a pot holding nearly 100 gallons of boiling water. By this means there are no loose grounds in the pot, and the coffee in the cloth looks like an immense plum pudding.…The dinner is served on wooden plates, each person being given a tin-cupful of coffee, a pickle, a sweet potato, a piece of beef and mutton, bread in abundance, and sometimes cheese. The coffee is taken from the pot to the long tables in buckets, and the bread is sliced and carried in barrels.

Jackson Citizen Patriot, December 12, 1884

CONTEMPORARY VIRGINIA BARBECUE

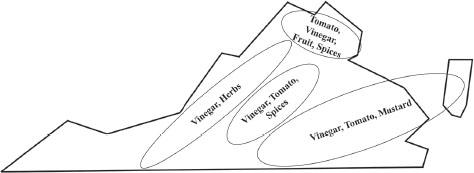

Virginia’s regional barbecue sauces became famous first in the region of the state where restaurants or vendors first served them. Therefore, the Virginia barbecue map depicts the regions of Virginia with restaurants and vendors who are famous for originating each particular regional sauce style—not necessarily just the regions where they can be found today. Moreover, all of the regional styles have roots in Virginia that go back to colonial times.

Today, you can find the various regional Virginia barbecue sauces just about anywhere in the state, fortunately. Therefore, in addition to calling them by their home region, Virginia barbecue sauces are often named from their color or consistency. For example, you can find Virginia red sauces, Virginia brown sauces and Virginia mahogany sauces.

Virginia’s regional barbecue styles. Author’s collection.

The Shenandoah Valley and Mountain Regions

Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley and Mountain regions are home to delicious Virginia-style, vinegar-based barbecue sauces. The famous Shenandoah Valley barbecued chicken calls for a vinegar-based sauce that has a rich mixture of herbs. Some add tomato juice to it. A few others add a little red wine. The Mountain and Shenandoah Valley’s vinegar-based sauces may also include sweet spices and celery seed. However, I’m treading into top-secret territory, so I should move on to the next regional style.

The Southside and Tidewater Regions

Virginia’s Southside and the Tidewater regions gave us their vinegar/tomatobase sauces flavored with a hint of mustard. Of course, Virginians have used mustard in their barbecue sauces for hundreds of years. Unlike South Carolina, however, Virginians never used mustard as a base for barbecue sauce. Rather, they prefer to use it as a flavoring. For years, the owners of a barbecue restaurant in Hillsborough, North Carolina, served a Southside Virginia–style barbecue sauce. The restaurant owner won the secret recipe in a game of horseshoes played in Virginia.60

Central Virginia and the Piedmont Region

Central Virginia and Piedmont region sauces are reminiscent of the barbecue flavors found in Mary Randolph’s cookbook. Some are on the sweet side and may include a rich mixture of spices. Don’t be surprised if you find some with a good amount of sassafras or Worcestershire sauce in them, too. Another unique central Virginia barbecue sauce originally found in restaurants in the Chesterfield and Richmond areas is Virginia peanut barbecue sauce. It is a delicious tomato- and vinegar-based Virginia-style barbecue sauce with a hint of peanut butter, which pays homage to Virginia’s famous peanuts.

Northern Virginia

Northern Virginia barbecue sauces are usually tomato based and often sweeter than the other Virginia varieties. They, too, are seasoned with sweet herbs and sweet spices and may include fruit in some form.61

VIRGINIA-STYLE BARBECUE RECIPES

The resources cited here provide many delicious recipes for authentic Virginia barbecue, and the reader should refer to them for recipes. Inspiration for the recipes that follow came from delicious Virginia barbecue served by restaurants and vendors today. The recipes are not exact clones but do represent the flavors and styles of the regional Virginia barbecue sauces. I recommend that you add your own “wok presence” to the basic recipes while taking care to maintain their Virginian character. Ingredients like agave nectar, jalapeño powder, truffles, teriyaki and pineapple may taste good, but they have no place in authentic Virginia barbecue sauces.

A Virginia Barbecue, in a shady grove, near a cool spring, with good speakers, who are gentlemen, and a gathering of Virginia ladies and Virginia farmers, kindness, courtesy, and hospitality prevailing, tops all other political assemblages or mass meetings! There is nothing like it elsewhere!

Alexandria Gazette, June 30, 1860

Virginia-Style Barbecue Rub

You’d be surprised at how many Virginia pit masters there are who don’t put rubs on meats before barbecuing them. Nevertheless, if you want to use a rub, here is one made of the flavors that are in traditional Virginia barbecue. Experiment with the quantities of ingredients to suit your own taste. Also, try celery salt or seasoned salt in place of the table salt.

1 part table salt

2 parts coarse ground black pepper

½ part red pepper flakes

1 tablespoon of molasses (optional)

Mix the salt and peppers well. An optional step is to apply a thin coating of molasses to the meat before seasoning it with the rub. Use on all meats.

Virginia Mountain–Style Barbecue Sauce: Thin Virginia Red

Add a hint of mustard to this recipe for a Southside twist.

1¼ cups apple cider vinegar

1 cup tomato juice

1 teaspoon brown sugar

1 teaspoon black pepper

1 tablespoon celery salt

1 teaspoon sweet paprika

1 teaspoon Worcestershire sauce

½ teaspoon poultry seasoning (or any sweet herbs you like)

½ teaspoon ground cayenne pepper or a pinch red pepper flakes (optional)

Mix all ingredients well and serve.

Shenandoah Valley–Style Barbecue Sauce: Thin Virginia Brown

½ cup oil (peanut, soybean or canola)

2 cups apple cider vinegar

3 tablespoons salt

1 teaspoon black pepper

1 teaspoon red pepper flakes

2 teaspoons poultry seasoning (or whatever sweet herbs you like)

1 teaspoon granulated garlic

juice of 1 lemon

1 cup tomato juice (optional)

Mix all ingredients well. Use as a basting liquid for chicken or pork. “Anoint” the barbecue with the sauce every 30 minutes while cooking. To use as a table sauce, reduce the salt by half.

Southside-Style Barbecue Sauce: Tangy Virginia Brown

1¼ cups apple cider vinegar

¾ cup tomato ketchup

2 tablespoons yellow mustard

2 tablespoons water (or to taste)

1 teaspoon black pepper

1 teaspoon table salt

1 teaspoon sweet paprika

1 teaspoon brown sugar (optional)

fine ground cayenne pepper to taste

Mix all ingredients well and serve. If the sauce is too acidic, add water to taste.

Central Virginia–Style Barbecue Sauce: Sweet Virginia Red

1 cup tomato ketchup

1 cup apple cider vinegar

1¼ cups light brown sugar

4 tablespoons mushroom ketchup or Worcestershire sauce

1 teaspoon sweet paprika

1 teaspoon black pepper (or to taste)

1 teaspoon salt

dash fine ground cayenne pepper (or to taste)

Mix all ingredients in a saucepan. Bring to a simmer, stirring as needed. Remove from heat, cool and serve.

Northern Virginia–Style Barbecue Sauce: Sweet Virginia Mahogany

1½ cups tomato ketchup

½ cup apple cider vinegar

½ cup apple butter

¾ cup dark brown sugar

1 teaspoon black pepper

1 teaspoon salt

1 tablespoon lemon juice

In a saucepan, mix all ingredients except the lemon juice. Bring to a simmer, stirring as needed. Remove from heat, stir in lemon juice, let cool and serve.