1

The Way of Nature Is No Ideology or Theology

When the word Taoism is uttered, many people identify it with a religion. But was Lao-tzu teaching and setting up an organized religion? Similarly we could ask whether the intent of Jesus of Nazareth was to create Christianity or whether Siddhartha Gautama’s intent was to create Buddhism. Throughout history we discover that religions are often formed many years after the focal point of a religion’s doctrine, in the form of an enlightened sage, has died. The intent of all legendary sages is to liberate the individual from the shackles of separation and suffering.

The legends of Lao-tzu, Krishna, Rama, Gautama the Buddha, and Jesus of Nazareth align with each other through an ineffable mystery that is veiled within their stories. None of these sages mandated that a religion should be organized around a group of precepts. On the contrary, they had no interest in setting up dogmas based around their teachings, because the essence of their teachings is a formless mystery. We invariably create dogmas when we do not understand the depth of the knowledge we are trying to comprehend. As a result, we cloak such knowledge by giving it a name and form in order to try and somehow make sense of it. This appears to be a typical psychological trait that shelters us from the real essence of what we are trying to know.

In many cases, words such as Tao, Brahman, Tathata, Allah, Akasha, God, and so on, conjure up an air of confusion for the average individual because the bulk of humanity do not observe or center themselves upon the source of the world, which is within oneself. Most people are focused on the outside world and are subject to the hypnotic belief that this is where the world exists. As a result, when they hear a word such as God, they cannot conceive of “what” it is. They mold its meaning to the world they think they know, which is the world of form and pleasure. Hypnotically, we give anthropomorphic form to that mystery. This somehow appeases our intellect, and we think we have figured out that God is some sort of Being above us, lording it over everything. Religious wars are waged tirelessly from this absurd monarchical view of God. This tyrannical view is also found in Taoism as a religious notion, which would bring a confused look to the face of Lao-tzu.

THE TAO OF THE OLD MASTER

Out of all the spiritual paths lived by the legendary sages, Taoism would be the least likely to have become a religion. Never did Lao-tzu explain a doctrine that one could follow. He knew that this would wind up in intellectual conjecture. The Taoism of Lao-tzu was about the Way, the Tao, which is something we experience when we are more attentive to our inner and outer worlds. The Tao can be followed and experientially known when we have surrendered our controlled, conditioned identity over to the effortless realm of spontaneity and trust, wu-wei. This effortless realm is why the Tao is usually referred to as “the way of nature,” because when we follow the Way, we can experience the same spontaneity of nature within our own experience; as a result, we trust our path through life. The discovery of this spontaneity in life allows us to sink deeply into the awareness that we are nature and not separate from any aspect of it. This revelation of oneness with nature reveals a close relationship between the shamanic traditions of antiquity and the wisdom of Lao-tzu, minus the rites and rituals. In the essential teaching of Lao-tzu we discover small traces of some connection to the ancient shamanic traditions of China going way back into the Shang dynasty (1600–1046 BCE).

But in no way could there be any connection to shamanic practices, ancestral worship, sacrifice, rites, and rituals, because knowing and following the Tao according to Lao-tzu has nothing to do with outward gestures, no matter how dazzling to the eye. All forms of practice and ritual are controlling aspects of the intellect and its repetitive modes rather than natural spontaneity. We could say, however, that in ancient times they were performed because they expressed the concealed mystical truth of Tao. Lao-tzu was not against such activities, but he did become concerned when people viewed them as a form of liberation.

Both the great sages Lao-tzu and Chuang-tzu explained that the real Way of Tao is beyond the outward form. Instead of being concerned with the temporality of such things as rituals, we can directly access the depth of our being through the feminine quality of wu-wei. Yet the teachings of Lao-tzu have been discarded in favor of the shamanic practices, ancestral worship, sacrifice, rites, and rituals that have developed and been embraced by the world since his time. All of this came about from the misinterpretation of Lao-tzu’s teachings by the social moralist Confucius and others down the line of history.

CONFUCIAN MORALITY AND THE PHILOSOPHY OF JU

Confucianism is still the predominant philosophy of East Asia. Aspects of Confucianism are not only found in China but are embedded in many different ideologies around the world. Confucianism is the moral and ethical outgrowth from the Taoist philosophy of Lao-tzu. We could only hazard a guess about whether Lao-tzu and Confucius knew each other.

When we study the mind of Confucius, we discover a man who understood the Taoist Way well and was a key contributor to the classic Taoist oracle the I Ching. But when we dissect the moral virtue of Confucius’s superior man, we discover that his interpretation of Lao-tzu’s wisdom may have only reached an intellectual level. This is because his primary focus was not on the liberation of the individual but on an enlightened society. I am not saying here that an enlightened society is impossible. But it needs to be clear that the foundation of a society comes from what is within the minds of the individuals who live in it. Hence Lao-tzu’s insight is that the enlightenment of the individual takes us a step closer to the total liberation of humankind.

This should make complete sense to anybody. Yet we have devised a whole social system of thought based on the concept that it is not the individual pieces that make up the whole, but rather it is the whole that controls the pieces. Surely you can recognize this idiosyncratic view of life within yourself. The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche once said in regard to morality within society, “Morality—the idiosyncrasy of decadents, with the ulterior motive of revenging themselves on life—successfully.”1

This concept has led to the formation of institutional power, which wields its influence over the individual through government, religion, the economy, academia, and other institutions. Confucius’s interpretation of Lao-tzu’s wisdom contributed heavily to this confused view of reality. Confucianism was not an enhancement of the Taoist Way. On the contrary, it deformed its wisdom into a vehicle that would only suit the morally and ethically “noble” of society. The Confucian way is to try and transform the individual according to the moral codes and ethics of ju (儒: Wade-Giles ju, Pinyin ru) philosophy.

Ju philosophy is the heart of Confucius’s teachings and the framework of Confucianism. It is constructed around four basic virtues (see figure 1.1). The first of these basic virtues is known in Chinese as jen (仁: Wade-Giles jen, Pinyin ren), which is translated in English as “human-heartedness.” This human-heartedness is the compassion and devotional love we have deep down for one another. It is the ability to identify with the suffering and joy of others as if they were our own.

The second virtue is called yi (義: Wade-Giles I, Pinyin yi) in Chinese, which is the sense of justice, responsibility, duty, and obligations to others. We need to be mindful that both jen and yi are disinterested states: the superior man does not do anything that will please or profit himself, because jen and yi emanate from an unconditional moral imperative.

The third virtue is the Confucian concept of li (禮: Wade-Giles li, Pinyin li). But this principle is somewhat different from the Taoist li (理), which we have briefly mentioned in the introduction and will discuss at length within this book. Li in the Confucian ju philosophy is the acting out of love and veneration for those relationships that make up the identity of our life—for example, family, one’s people, and also heaven and earth. Li in this case is the liturgical contemplation of the religious and metaphysical structure of an individual. In the li of ju philosophy, an individual is grateful to take his place in the social and cosmic order of life.

The fourth and final virtue is chih (智: Wade-Giles chih, Pinyin zhi), which means wisdom in Chinese. Chih combines the three other virtues into a religious maturity whereby one follows a spontaneous inner obedience toward heaven, rather than being moved by external influences.

Figure 1.1. The four basic virtues of ju philosophy By Dao Stew

Though ju philosophy may sound admirable compared to our modern code of conduct, it is still an artificial construct attempting to make the individual conform to a set of rules and a system of behavior. This fosters social unrest, because the individual loses her naturalness. The Confucian philosophy of ju still dictates a set of standard laws to the individual. As a result it is fundamentally flawed, because it implies that we do not belong to this world, and instead need a doctrine to live by.

LAO-TZU’S NATURAL INDIVIDUAL VERSUS CONFUCIUS’S SOCIAL ETHICS

The Taoism of Lao-tzu emphasizes that if we do not let individuals grow as nature intended, they will lose their naturalness and be drawn into the world of animal drives, desires, attachments, and ultimately suffering. This difference in the depth of understanding between Lao-tzu and Confucius is articulated in an imaginary dialogue created by Chuang-tzu:

“Tell me,” said Lao-tzu, “in what consist charity and duty to one’s neighbour?”

“They consist,” answered Confucius, “in a capacity for rejoicing in all things; in universal love, without the element of self. These are the characteristics of charity and duty to one’s neighbour.”

“What stuff!” cried Lao-tzu. “Does not universal love contradict itself? Is not your elimination of self a positive manifestation of self? Sir, if you would cause the empire not to lose its source of nourishment—there is the universe, its regularity is unceasing; there are the sun and moon, their brightness is unceasing; there are the stars, their groupings never change; there are the birds and beasts, they flock together without varying; there are the trees and shrubs, they grow upwards without exception. Be like these: follow Tao, and you will be perfect. Why then these vain struggles after charity and duty to one’s neighbour, as though beating a drum in search of a fugitive. Alas! Sir, you have brought much confusion into the mind of man.”2

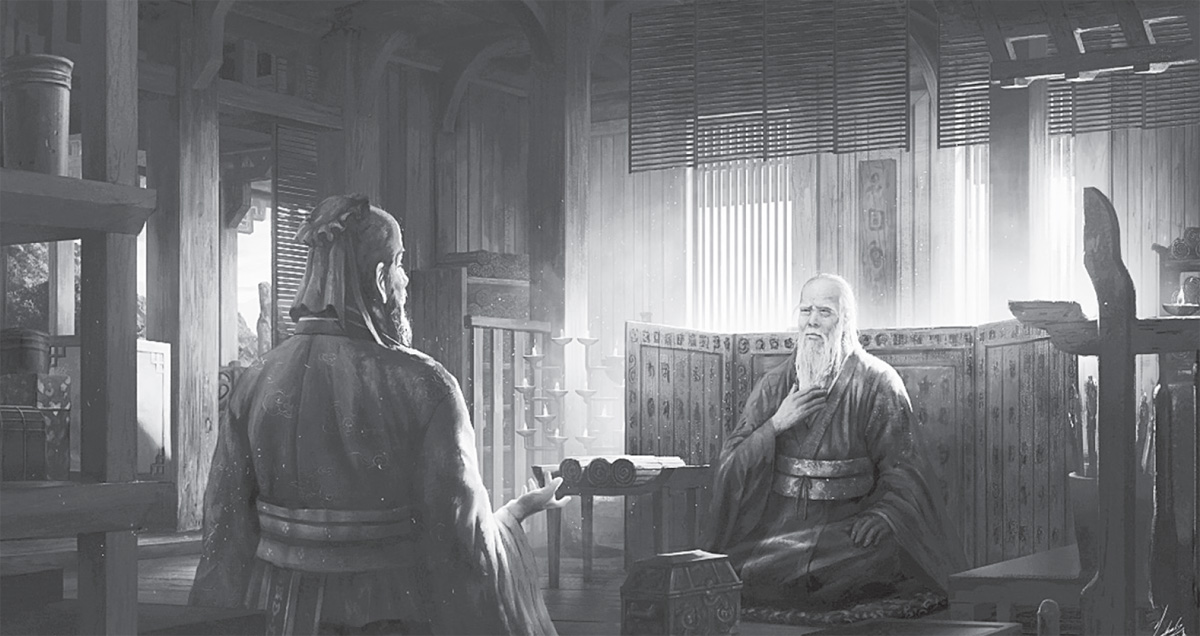

Figure 1.2. Confucius and Lao-tzu in dialogue By Jiwon Kim

In this imaginary dialogue, Lao-tzu reiterates that if we interfere in the natural process of any living organism, it will begin to isolate itself from the complementary parts of the whole. This isolation brings about a disassociation from the whole, so that a lack of trust plagues the mind.

Confucius’s ideas of charity and duty to one’s neighbor are age-old teachings, which artists, philosophers, and spiritual teachers have contemplated from the dawn of civilization to the present day. On the surface, we may all feel convinced that he is correct in postulating that we have a duty to others. But the Taoist Way of Lao-tzu suggests that in attempting to interfere with others’ affairs, no matter how large or small, we are assuming that the natural experience of life is not happening spontaneously; instead we think that life is a series of controlled steps following a predictable and mechanical process. Lao-tzu is not saying that we should abolish duty or charity. He is saying that everything in the universe is integral and symbiotic in nature, and that everything functions harmoniously according to the rhythm of the universe. So, he asks, why would humanity be the exception? The Way of the Tao and our experience of it comes from allowing all aspects of the universe to happen as they will without conscious interference.

This understanding of Tao is a trust in and affirmation of life that cannot be broken. Humanity’s superficial differences could be dissolved if each individual could live by this trust. Yet society and culture have been built on ideologies such as Confucianism, communism, and democracy, which all teach us in some way to impose our will over one another, a goal based on the erroneous idea that we are achieving freedom in this process. To trust the Way of the Tao is the complete backflip to Confucianism or any present-day ideology or theology. Lao-tzu’s wisdom exposes humanity’s selfish tendency to impose the will of one individual, nation, religion, race, or gender over another. We are always interfering with each other’s natural sovereignty. Many people arrogantly and ignorantly do this daily and then proclaim that they know what freedom and love are. How can we listen and help each other if it is merely from our own cultural, social, or religious perspective? If we have a set of beliefs to sell another, then we are surely imposing our idea of life upon her without letting her grow as nature intended.

It is this personal agenda that Lao-tzu reveals. If we interfere unnecessarily with any organism on this planet, we hinder its growth through our attempt to control it. When it is interfered with, an organism finds itself in a struggle to grow into everything it should be. As a result, the organism’s natural impulse to grow is met with resistance by another organism, which assumes that it is superior to all life and needs no other organisms to survive. We could say human beings fit perfectly into this category because of the personal agendas we wish to cast upon the world. These agendas could only have developed in a world devoid of trust. Because we live in fear instead of trust, our world is designed so clinically that it resembles not a beautiful garden but a morgue.

The Confucian imperative to dictate a social way of life to the individual builds an identity conditioned by the world of concepts and objects rather than the inner world of emotions, feelings, and thoughts. Yet we should not be critical of the Confucian perspective only, because any ideology or theology, no matter how well intended, is at its foundation strictly a methodology for shaping the individual according to its beliefs. Lao-tzu points to this in the Tao Te Ching. He says that humanity is in a perpetual trap in which we seek to change one another or society based on our own belief systems. Because we have not made our inner world conscious, we continue to seek change in the external world of forms, as if the inner world were a construct of the outer. Many theologies and ideologies operate from this perspective. But this is an absurd view for the simple reason that the world is devoid of meaning until the observer gives it meaning according to her beliefs. This should be fundamental to the way we think and perceive the world. But instead we are told that the world is purely material by the teachers of our cultural, social, religious, and educational machine, who themselves have been indoctrinated.

To cultivate a sane society, we first need to understand that our perception was pure before it was colored by external influences. And all of these external influences are interpreted differently by each individual, which adds to the confusion. Patanjali, the great sage of India and father of yoga, expresses this sentiment in the wisdom of three of his sutras regarding freedom:

People perceive the same object differently, as each person’s perception follows a separate path from another’s.

But the object is not dependent on either of those perceptions; if it were, what would happen to it when nobody was looking?

An object is known only by a consciousness it has colored; otherwise it is not known.3

We have built a world that operates in reverse to the natural order of growth and harmonious living. The world’s general view identifies with what colors consciousness rather than with the unbound and limitless pure awareness at the core of our being. Lao-tzu’s essential teaching of wu-wei is a medicine for this illness.

But you must understand that wu-wei is not an ideology, theology, or something you need to believe in. On the contrary, wu-wei can only be known through your own experience. Then it simply strengthens your trust in wu-wei. The natural order of growth and harmony depends upon allowing life to take its course without conscious interference. This is how the Tao flows when wu-wei is experienced. Many people resist the very thought of allowing things to take place in life, because from our perspective we can’t see how anything could be achieved in that way. But if we are more observant, we discover that each and every attempt to categorically control our life is invariably upended by the spontaneity of natural experience. No human being is above this universal spontaneity. And yet many people seek to control life down to the finest detail, failing to realize that the very things that shaped their identity were beyond their control.

THE PHANTOMS OF CONTROL AND SECURITY

Pain comes when the control we think we have comes crashing down in the light of reality. We fail to realize that the ability to imagine is a vehicle we use to try and control our future. These future projections may be pleasurable, but usually these pleasurable experiences do not come to fruition. Yet we cringe at the reality of living completely in the here and now.

Control is nothing more than an attempt to bring the past and future under our command. Our personal agendas are secret ways of trying to control the destiny of others based on the memories of our past. The pure, natural awareness of our consciousness is polluted by the illusion that we can control each and every situation in life. Spontaneity is loathed by many people; it conflicts with their incessant control. The transformation of Lao-tzu’s Taoism into Confucianism is no different.

Lao-tzu exemplifies the rebel in the truest sense of the word, because, following the effortless grace of wu-wei, he is uninterested in worldly affairs. The Taoist Way is not to lord it over anything or anyone. All aspects of nature are allowed to run their course without interference. Sometimes, however, skillful guidance can be given by those who have realized the Tao and function according to wu-wei. But when we unskillfully attempt to tell another individual what to do, how to think, or how to be, we are in fact destroying that individual. Parents are the best example. They project their own idea of the world onto their children without letting them follow their own interests. Parents in such a state of control do not love their children unconditionally. On the contrary, they want for their children what is acceptable in the eyes of the society and world. In this way, we treat children as meaningless material objects. And yet this model is accepted as parenting par excellence.

This vicious cycle of hypnotic parenting can only manifest in a society and culture that have stripped the trust in life out of people. In one sense, our parents are not to blame. But on the other hand, they are to blame, because like everyone else in this world, they are naturally sovereign and have a responsibility to avoid imposing their agendas onto others. In this case a family becomes the microcosm of the society in which it dwells. Parents become hierarchical tyrants who terrorize their children with indoctrination. When an ideology, such as democracy or Confucianism, imposes its idea of life upon our minds, we begin a lifelong journey of suppressing our natural inclinations and the creative expression for freedom. This suppression strangles the innate power that we all possess. And when we lose our innate power, we seek to project it into avenues that we feel comfortable in controlling.

All types of personal relationships exhibit this constant game of one-upmanship. It’s not only evident in parents and children but can be found in intimate relationships, such as those between husband and wife. There is always a constant battle for power; each party is trying to make the other yield to his own idea of how life should be. They are attracted to power because society is based on an artificial system that teaches the individual to chase material comforts and convenience in the belief that this will bring security. Our indoctrination teaches us that the more possessions we have, the more powerful and successful we are, and power lies in what is used to acquire these possessions. The symbol of power in our world is money. Yet money itself is empty and valueless until we give it value. We discover that this is true when we realize that the wealthiest people on this planet are usually the unhappiest.

The impulse to control life is a symptom of the power that we believe we have lost. But true power resides in the mind of one who is liberated from the acquisition of wealth and the control of others. When we give up attempting to control life, we find that we are no longer clinging to or conditioned by any aspect of life. Thus we are freed from its attachments. The most liberated people on this planet have been those who were free in this way, such as the twentieth-century Indian sage Sri Ramana Maharshi.

THE SUPERIOR MAN

Confucius audaciously tried to bring morality and ethics into the consciousness of humanity with his concept of the superior man, known as junzi (君子: Wade-Giles chün-tzu, Pinyin junzi) in Chinese. Keep in mind that although the Taoist perspective uses the term superior man to refer to both men and women, this is not the case in Confucianism, because Confucius was not overly confident in women’s ability to attain wisdom. Superior man, according to Confucius, literally meant man. Indeed his view of the superior man is that of a man who acts outwardly in a cultured and learned manner, very much like the English concept of the gentleman. Nevertheless, Confucius did point out that a man of any social class could be a superior man if he cultivates the virtues of ju in his character.

Here is where Confucius and Lao-tzu’s views of the superior man differ: Confucius believes that we are naturally born with rough edges; we are almost beastlike. As a result, we need to chisel away at our being to mold it into a human shape. This is his philosophy of “carving and polishing.” Lao-tzu, on the other hand, believed that we are naturally pure; it is the belief systems and social indoctrination of the world that give us a gross character and warp our pure nature. As a result, we need to get back to the raw, intrinsically human, elements of our being. This is known as returning to the “uncarved block” or “unhewn wood.” Lao-tzu’s teaching of wu-wei is not a method of telling the individual how to be like the superior man, but instead it gives the individual the knowledge of how to become the superior man.

An individual with an effortless mind resulting from the practice of wu-wei travels with the stream to its source, which is the ocean of Tao. When we attempt to control life, we are assuming that we do not belong to the universe, so we begin to drown in the current of change. This lack of trust in the universe comes from the way we orient our perception toward the world. In believing that external influences control life, we have a psychological tendency to worship those influences. We become bound by what comes through our senses. This breeds artificiality, because the individual worships what is conceptual.