4

The Virtue of the Nonvirtuous

The organic pattern of li is a riddle to our conventional way of thinking. This riddle can be explored by three questions: How can we discover or be in accord with our li without being ambitious? How do we try not to try to be in the effortlessness of wu-wei? How do we become natural with no effort? From the perspective of Lao-tzu, seeking and ambition are bound to a linear model of the world, but the li that we seek out originates in the nonlinear world of spontaneity. Searching for our own li is a paradox that can tie us in knots. If you “follow your bliss,” as the American mythologist Joseph Campbell suggests, how do you eradicate ambition from your mind? The little occult classic Light on the Path by Mabel Collins delves into ambition’s paradoxical nature in its first four precepts:

- Kill out ambition. [ . . . ]

- Kill out desire of life.

- Kill out desire of comfort.

- Work as those work who are ambitious. Respect life as those who desire it. Be happy as those are who live for happiness.1

These four precepts would cause a world of confusion to a mind plagued by ignorance. But for those people who have deepened their introspection, they are essential for liberating the intellect from the hypnosis of linear continuity.

To assimilate these precepts, we need to understand how they can be perceived from two different perspectives. From one perspective, we long to create, and yet from another, absolute creativity is intrinsic to our nature and can only be accessed in the present moment. The relative version of ambition is the most common one in our world. It makes people strive incessantly for results from their creativity, as if the result were more important than the process. In this way ambition in pursuit of social success becomes insanity.

The ambition we need to “kill out,” as Light on the Path suggests, is relative ambition, which is tied to the linear perception of past and future. This view runs in the opposite direction to Lao-tzu’s and also to the Buddha’s teaching that happiness is really contentment in every moment of life, while happiness in the sphere of linear ambition is only achieved momentarily, in the end result. Contentment is discovered with Collins’s fourth precept: one has let go of striving for a result and instead become content with a process that is driven by one’s li when ying (mutual resonance) occurs. Li, from the Taoist perspective, is an absolute principle that belongs to the universe. This real ambition, which we discover in our li, is the intrinsic virtue of the Tao. In the natural, nonlinear world of li, a creative process is hindered when it is planned. A true creative process and the essence of art is that your virtue can only come through your li when you have thrown off the idea of planning and striving, and instead opened yourself up to the present moment, where the natural harmony of li will grow spontaneously.

The cosmic fragrance within the universe is the virtue of the li pattern found within all organisms. Real virtue is different from the virtue of Confucian thought, as well as from the modern goal of ambition for success. Li’s artistic expression is produced by a virtue that arises spontaneously, without forethought or intellectual contrivance. This virtue naturally and spontaneously dawns upon the individual when the power they seek subsides into an honest humility. This natural virtue is known in Chinese as te (德: Wade-Giles te, Pinyin de, see figure 4.1) and in Sanskrit as dharma. (In Chinese te can mean power or virtue, depending on how it is used. Dharma is an inclusive word that can mean duty, mission, law, the Buddha’s teaching, and virtue. In classical texts the two terms are often used interchangeably.) The te, or dharma, of the ancients is rarely found in humanity. In many cases it is only recognized in the inspirational expressions of an artist or the wisdom of a sage. A small minority of artists and sages have access to this realm because they have naturally fallen into the nonlinear world of the present moment, where their li harmonizes with the world and inspires it as a result. The te of a sage and artist is readily available and never contrived.

VIRTUE OF TE

Te is not isolated to certain individuals; on the contrary, it is the innate cosmic nature that we all possess, as these aspects of our nature are absolute qualities of consciousness.

So if these aspects are our innate nature, why does te only come through the mind of the inspired individual? Te is as nature is; it cannot be induced or contrived, because it manifests naturally through one’s experience. The answer, then, is that our motives ruin the natural unfoldment of consciousness. Our world is so hell-bent on acquiring power that we lose sight of how anything in this world is produced. When we exhibit force or seek power, the underlying motive is the instinctual impulse for survival. This tendency reinforces the illusion that we do not belong to the world.

Figure 4.1. Te—universal virtue By Dao Stew

Our current anxiety for survival is manifest in the world through individual and social unrest, not to mention ceaseless wars that occur around the globe. The ambition that drives us toward social and material success is none other than our vain attempt to stand on the shoulders of others, as if we were somehow above others in the pecking order. These lower drives have remained in our minds from our evolution out of the animal kingdom. And the materialistic notion of “survival of the fittest” has not helped. Yet such seemingly concrete theories are slowly being torn down, because they are causing a kind of entropy in the human race. The growth of anything in nature cannot be forced, nor could there be anything to achieve from such a conquest.

In much the same way, the higher states of consciousness that lead to evolution and enlightenment are not things one can force or induce. Virtue, or te, cannot be thought of as something to acquire. This was the issue that brought about differing views between Confucius on the one hand and Lao-tzu and Chuang-tzu on the other. Confucius thought that the virtue of te was something that one could cultivate and induce, as he did not believe that it already belonged to one’s own consciousness. This perspective is still aligned with a searching and striving for power, and it is diametrically opposed to Lao-tzu’s. In Lao-tzu’s Tao Te Ching, he explains that the highest virtue is nonvirtuous, so “therefore it has virtue.” And paradoxically he states, “Low virtue never frees itself from virtuousness, therefore it has no virtue.” The virtue of the Tao Te Ching is without intellectual meaning because true virtuousness is beyond virtue. It’s not something requiring thought. The te of the sage is a quality beyond the parameters of the linear world.

Trying to discover or induce the power of virtue implies that we do not possess it already. The virtue of the nonvirtuous, or te, is only available to those who do not use force or seek power. When we fervently seek power or use force, we exhaust our system by swimming against the current of life instead of flowing with it. A sage or an artist allows life to present itself instead of dictating toward life. Skillful athletes also follow this template of effortlessness.

When you finally realize, beyond intellectual speculation, that the whole universe is happening to you right now all at once, you will cease projecting yourself onto the world, because you will become receptive to the universe. This will align you with a real trust in life that confirms that you belong. Your li is a nonlinear pattern that organically grows out of the universe to bring harmony to the world. The li of each individual belongs to this universe, but sadly, very few discover this essence because of a world that is built on the blindness of force and power.

When a large number of the human race are not living their own li, they contribute to entropy. When te does not shine through us as individuals, we are inherently led into distractions. And we currently live in a world full of distractions, which keep our attention hypnotically away from the world within. Distractions become our sole focus, because they engage us in the sense-perceptible world with which we mistakenly identify. When we pollute the senses with external stimuli, there is no chance that the light of te can come through our minds.

ALLOWING THE LIGHT OF VIRTUE TO SHINE THROUGH THE DARK CLOUDS OF MIND

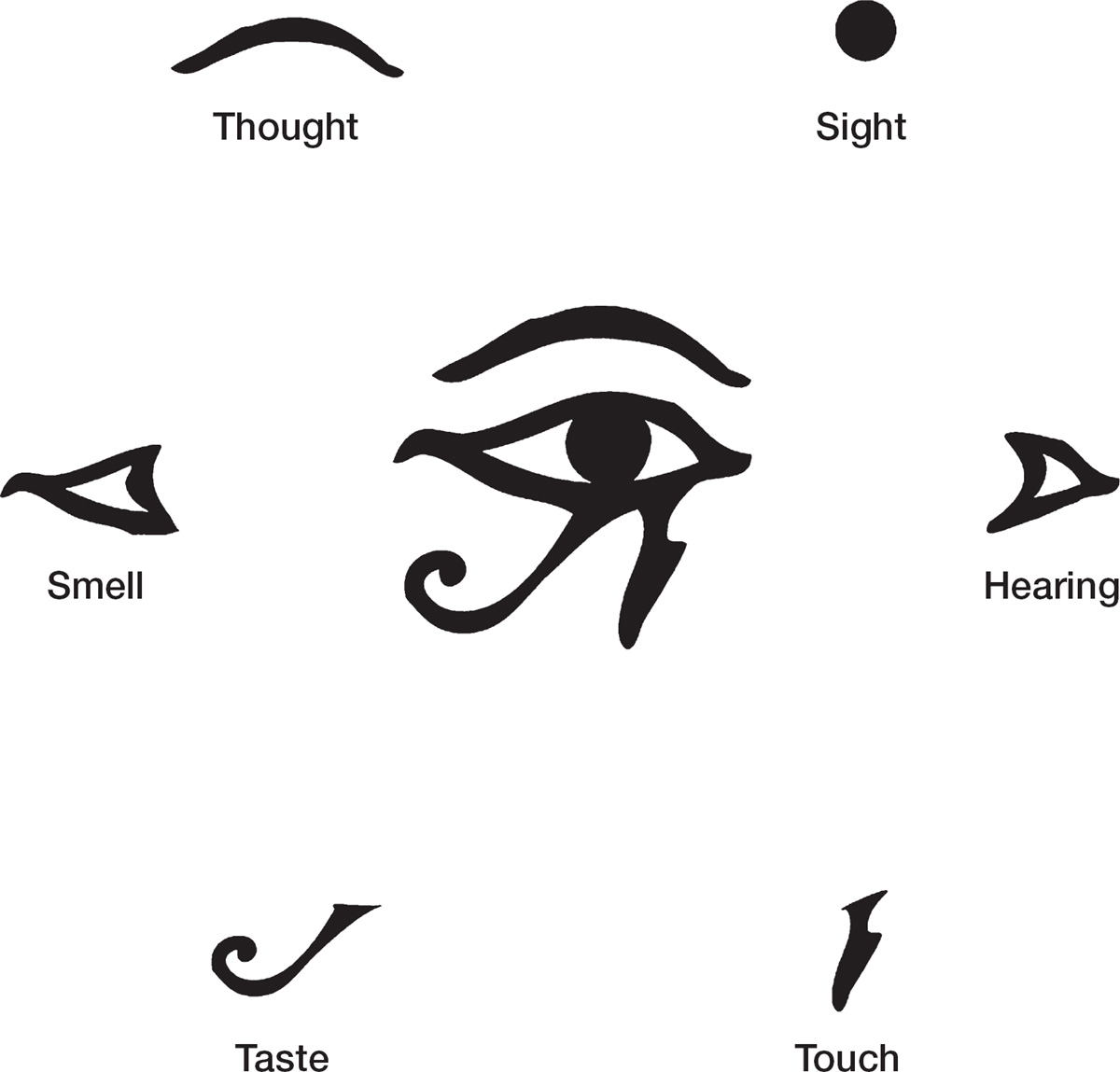

The wisdom traditions teach us to be conscious of the nine gates of the human body. These gates are the two eyes, two ears, two nostrils, mouth, penis or vagina, and anus. They stimulate the six senses, which are smell, touch, taste, seeing, hearing, and thought. (The wisdom traditions teach that thought is the sixth sense and that it is influenced by the energy we consume through the other five senses.) The “Eye of Horus” in Egyptian symbolism, known as wadjet in Egyptian, is an image that contains the philosophy of the six senses (see figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2. The Eye of Horus: The Six-Sense Philosophy By Dao Stew

When we refrain from bombarding the senses with pleasurable stimuli, the virtue of te is more likely to shine through the mind. But it is the sense of thought that, in many cases, distorts the awareness of virtue, because one has not experienced nirodha, stilling of the mind. The question, then, is, how can we sincerely attain the virtue of the nonvirtuous? Te is an absolute quality of Tao; it is omnipresent, yet in many individuals it is veiled, like the sun on a dark and stormy day.

All of the energy we consume, whether it be food, beverage, or impressions, contributes to our emotional, feeling, and thinking states. The way we receive and transform energy is continually suppressing the virtue of te, because the energy we choose for our physical and mental well-being is almost invariably toxic. From the food we eat to the liquid we drink and the impressions we allow through our eyes and ears, we are constantly poisoning ourselves through a pursuit of pleasure, as entertainment becomes more valuable than health.

According to the ancient sciences of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and ayurveda of India, the cleaner the fuel, the purer the thought vibrations within the mind. Even though this should be obvious, it is not, because we have divided the functions of the mind and body into separate components. But the body and mind are themselves ying: they are interdependent systems, which, when brought into harmony, allow for the spiritual plane of consciousness to come through.

The health aspect of finding one’s te is really only a piece of the puzzle. The well-being of the body and mind may settle the energetic streams of the human organism, but in the majority of cases this does not clear out the vasanas (Sanskrit for latent tendencies and habitual ways) deep within consciousness that affect our karma (Sanskrit for action), and both of these continue to reinforce our samskaras (Sanskrit for mental impressions or subliminal psychological imprints) that bind us to the wheel of samsara, the endless cycle of suffering. This process of purifying our karma, vasanas, and samskaras is explored at length in my book Fasting the Mind, which focuses on the tools and framework that facilitate this complete transformation. In Fasting the Mind I explain this process of fundamental transformation through the relationship between karma, vasanas, and samskaras, but in brief this is the process:

To dig into our samskaras, and thus to escape the wheel of samsara, we need to work backward, beginning with karma. When we realize the dilemma we are in, we start to examine our actions, questioning our habits and tendencies. This process is achieved through the science of mind fasting (which I will discuss later in this book). Exploring our karmic actions, we need to start taking away the familiar distractions that alert us to act. We need to refrain altogether from acting toward the world for a certain amount of time.

Our samskaras begin to be transformed when we have worked through our karma and vasanas (the two limbs of the samskaras). Having stopped our usual unconscious movement of actions and habits, we arrive at the subtle sensory level, the root level of the samskaras.

These latent tendencies and habitual ways originate from the hypnotic conditioning we have undergone from birth—the samskaras. But trying to alleviate vasanas, habits, through a practice that only focuses on the conscious connections between the body and mind is an egotistical attempt to deal with a spiritual symptom. It is like a marathon runner who thinks she can sprint the whole marathon. If she attempted this, it would not be too long before she burned out her system.

This system burnout is common among many practitioners of hatha yoga, qigong, t’ai chi, and other movement methods, including forms of dance. When we try to alleviate dormant vasanas solely through the conscious movement of energy between the body and mind, we can potentially exhaust our system. We discover this among many schools of spiritual cultivation, where the pursuit of alleviating vasanas to transform samskaras usually turns into a gross exhibition of spiritual pride. Just as an athlete becomes egotistically proud of his status and achievements, so does a spiritual seeker when she sets out to use primarily the body and mind to achieve enlightenment without transcending the conditioning that drives her sense of a separate and isolated identity. As a result, her conditioned identity grows deeper roots within the samskaras, which in turn show up even more powerfully in the way she expresses herself. Think of a peacock who is strutting its stuff, and you have a clear image of what is being said here.

The health of the conscious connection and movement between the body and mind is only one aspect of allowing the virtue of the nonvirtuous te to shine bright. For the sincere student, it can be a beautiful path and practice, but it can often lead to spiritual pride and peacock consciousness as a result of its emphasis on the physical, which is a common trap of the materialist mentality.

In ancient India this connection confused people for thousands of years, as the core of the Hindu philosophy of Vedanta, known as “The Science of Self-Realization,” was mainly thought of as a system of knowledge enabling one to attain a hygienic state within the physical and mental planes of consciousness. This process is incomplete, because, as many ancient wisdom traditions teach, consciousness is composed of three planes: the physical, mental, and spiritual. Many spiritual seekers in ancient times were missing the most crucial aspect for alleviating their vasanas and transforming their samskaras. That crucial aspect is the individual’s awareness of and relationship with the spiritual plane.

Like many wisdom traditions, Vedanta is a framework built upon the mysterious essence of the universe, known in Sanskrit as Brahman, which is the equivalent of the Chinese Tao. Vedanta was interpreted in many different ways over the course of time, because individuals who are not centered within themselves usually create superficial systems of beliefs around the actual teachings. These systems usually pertain only to the physical and mental planes of consciousness—the world we can experience—but not to that unexplainable essence beyond experience. As a result we become connoisseurs who are eating the menu.

PATANJALI’S YOGA OF MUTUALITY

These many differing interpretations of Vedanta changed when the great Indian sage and author of The Yoga-Sutras, known as Patanjali, brought clarity to the wisdom that came out of the Upanishadic era. Patanjali recognized the frustration of those who could not transcend their own karma, vasanas, or samskaras. According to Patanjali, the cure for this frustration is obvious: we have overemphasized the doing aspect of life as a result of our focus on the material world. Patanjali understood that virtue will never enter an individual if the doing aspect of the physical and mental planes is the only one activated. The spiritual plane was of the utmost importance to Patanjali. He set out to devise a system of liberation that would bring the light of dharma, or te, into the world.

In the two millennia since the time of Patanjali, yoga as we know it may have changed its outward garments, but its essence is the same. When Patanjali uses the word yoga, he is describing a “yoking” process in alignment with its Sanskrit root yuj, which means union, or in Patanjali’s view, absorption. His practice of yoga is intended to free consciousness from being habitually caught in a gravitational pull toward the external world. Yoga, in its purest essence, is to cease identifying with external things and instead to turn the attention inward to discover that underlying pure awareness known as Purusha in Sanskrit, which is the fragrance of Tao/Brahman/Tathata/Allah/God. Patanjali’s classical yoga avows a strict dualism between prakrti (the cosmos and its movement, energy, and matter, the physical and mental planes of consciousness) and Purusha (pure awareness of the transcendental Self). Purusha, according to Patanjali, is separate from prakrti, even though the fundamental purpose of prakrti is to realize Purusha and bring its essence into the world.

Patanjali’s original system, then, is not only hatha yoga (the common yoga practice that is associated with physical exercise and fitness), as the modern world mistakenly assumes. Nor is it isolated within the confines of the eight limbs of yoga (known in Sanskrit as yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi) or the seven paths and temperaments of yoga (known in Sanskrit as mantra, tantra, karma, raja, jnana, bhakti, and hatha). Patanjali brought back the archaic Vedanta system of union with the Godhead (yoga), which consists of combining a method of practice with nondoing—wu-wei. What was apparently obvious to Patanjali was that a lot of individuals are either busy practicing some form of spiritual cultivation or they are trying to remain in a contemplative state of nondoing, with both extremes ignorant of their mutuality. Patanjali understood that to practice a form of spiritual cultivation is the masculine, yang principle of the universe, and that nondoing is the feminine, yin principle of the universe. For Patanjali both practice and nondoing complement each other like husband and wife, yang and yin, Heaven and Earth, hot and cold.

Practice and nondoing are ying, interdependent, and “mutually arising.” This is known in Chinese as hsiang sheng (相生: Wade-Giles hsiang sheng, Pinyin xiangsheng; see figure 4.3). The mutual arising of practice and nondoing is a mirror of how the universe is. From the universal perspective, consciousness and matter arise mutually. In other words, the universe produces consciousness, and consciousness evokes the universe. Both are complementary—hsiang sheng—and depend on each other—ying. According to Patanjali, it is only when we bring practice and nondoing back together that we can give birth to the spiritual plane of consciousness. The masculine and feminine function in the same way on all planes, so it would be absurd to believe the doing of practice and the art of nondoing lie outside of this cosmic principle.

Figure 4.3. Hsiang sheng—mutual arising By Dao Stew

Nondoing in the context of wu-wei, as we have mentioned, is the nonforcing or noncontrolling aspect of the receptive nature of the universe, the yin, feminine principle. In Patanjali’s system of yoga, non-doing can be cultivated through the process of nirodha, stilling the mind. The more one sits in the quietude of stillness, the more one truly begins to live wu-wei. Stillness itself is yin. There is a resonance between being completely in the present moment of stillness, or nothingness, and the nonforcing expression of wu-wei.

It may be difficult to grasp why the more you can remain in the now of the present moment, the more you will be in the receptivity and humility of wu-wei. Nevertheless, this is the reality of our experience, as Patanjali and Lao-tzu knew. This experience is essentially the yin nourishing the yang, meaning that stillness benefits action in the same way that meditation is an advanced tool for the preservation of intellectual life. Patanjali’s formula requires a sincere approach to one’s own liberation, withdrawing one’s focus from the world of forms, both physical and mental, into a genuine introspection within oneself, which is where the world really resides. To practice this formula, we have to be sincere in what the ancient masters call “the great work of eternity.” It is only in the sincerity of the great work of eternity that we could bring the wisdom of the formless world into the world of forms, or in other words to bring Heaven to Earth.

We cannot have access to the virtue of the nonvirtuous, te, if we are continually attracted to the gravitational pull of the external world. If your attention is focused on worldly affairs, the Tao cannot make use of you, because your awareness is hypnotized to believe that the world of forms is a concrete reality.

But actually it is our perception that shapes reality, and everybody’s perception of reality differs. For example, something as simple as a tree “means” something different to each and every one of us through the way we feel and interpret what a tree is. And yet how could we interpret what a tree is? This extends to anything we perceive and experience in life. It is at the heart of many conflicts between religions, because the concept of God is interpreted differently as a result of dogmatic beliefs. Many of our problems are essentially matters of belief versus belief, with no true understanding.

The Taoism of Lao-tzu and Zen Buddhism, which are two of the more mature spiritual traditions on the planet, approach the interpretation of such concepts as God in a vaguer manner, but this vagueness actually gets to the heart of the matter more precisely. For example, in Taoism and Zen, to try and give God a meaning or interpretation is like trying to write on water. The actual reality escapes the use of language and words. So the more mature approach is to know and transform your inner world while allowing the outer world to run its own course without your interference. This approach adheres to Patanjali’s discovery that both the nondoing in the inner world and the individual doing of spiritual cultivation in the outer world reduce the propensity of consciousness to be pushed around by the play of form. This is what yoga truly is.

Even though many masters know that to be overly disciplined is a crutch, they are aware that spiritual discipline is necessary for those individuals who can only intellectualize the truth rather than actually feeling and experiencing it.

Practice and nondoing are necessary, because it is not until the settling of the mind, nirodha, occurs that the virtue of te will spring forth from the Tao through one’s own nature, li. An old analogy is that of the sun shining through a dirty window. The more sincere one becomes in transforming and transcending one’s inner conditioning, the cleaner the window becomes for the rays of the sun to shine through. The sun in this sense is the Tao, and the window is our mind.

BREAKING FREE OF THE MACHINE THROUGH VIRTUE

The virtue of Lao-tzu cannot be lived if the seals and veils of conditioning continue to obstruct the window of mind. The majority of the world’s population act out of their own seals and veils, hypnotically believing that they are their conditioning. Identifying with one’s conditioning is the state of the masses, and this position of rigidity, a state of sleep resembling mass hypnosis, in its turn generates an uncreative mentality and a lack of artistic virtue. Te is missing from a civilization when social, cultural, ideological, theological, and religious indoctrination is conditioned into individuals as a reality that they should abide by for their whole lives, without ever questioning its authority. The Catholic Church is a perfect example of this form of indoctrination.

Sages and artists throughout time have always questioned the authority of these institutions through their own te. They have never been concerned with opposing the machine with their own agendas, but instead their focus on te brings forth their organic pattern of li and so brings harmony to the world, regardless of the functioning of the social machine. This in turn inspires others to do the same by finding the li of their own intrinsic nature.

Te is coming from the formless realm of Tao, while the tyranny of the social, cultural, ideological, theological, and religious machine will always be limited to the incessant control of external life. Hence the machine has a use-by date, while te is limitless and eternal.

Though this is the reality of te, the masses have come to the point where they are behaving and living like machines. We are not computers or machines, but we have begun to mimic them. We remain continually disposed to being alien to this world, which only perpetuates our unnatural attraction toward the machine’s tyrannical operations. They keep humanity in a paranoid state focused on survival.

We begin to break free of such hypnosis when we sincerely open our minds and hearts to an unwavering trust in life. This trust is the alchemical ingredient that brings the naturalness of Tao, te, and li together as one. The human being corresponds to nature by allowing all aspects of universal life to take their natural course without conscious interference.

This is the ultimate spiritual revelation of Lao-tzu’s Taoism and the essential outcome of Patanjali’s system of integrated practice and nondoing. When the cultivation of stilling the mind through nondoing has taken root in the individual, the more receptivity, humility, and wu-wei begin to reveal themselves through his or her own being. Patanjali stressed this approach because he knew that the virtue of dharma/te can only come into this world through living wu-wei truthfully. You cannot discover your own natural virtue unless you live wu-wei. In completely focusing our attention within, we bring our inner and outer worlds into order. To trust the universe means to let life be without trying to impose our will over it in any way.

While letting life be may mean decay or death in the cycles of nature, the human kingdom is the only aspect of nature that actively and consciously opposes the growth of life through a parasitic desire to control its own experience. We have built a model for the world to follow on the back of this parasitic desire. We are opposed in all facets of our life by an unnatural system, both within and without, that goes against our natural trust in life. Trust can only be born when we as nature are allowed to express ourselves through te. Yet the inspiration that te brings into the world is constantly opposed by the unnatural illusion of control. As we grow both individually and collectively, it is imperative that we discard all unnatural systems so that we can go past our current pattern of entropy.