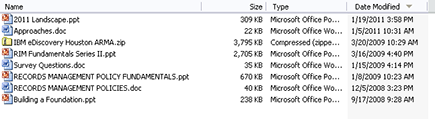

Figure 2-1: Date modified.

Chapter 2

Appraising

In This Chapter

Preparing for the records and information appraisal process

Preparing for the records and information appraisal process

Settling on an appraisal method

Settling on an appraisal method

Seeing an appraisal through

Seeing an appraisal through

Documenting what happened when

Documenting what happened when

Processing the appraisal

Processing the appraisal

The process of determining the value of records and information is known as the appraisal. The appraisal involves identifying, documenting, and evaluating the legal, fiscal, historical, and operational significance of company records and information for disposition purposes. The appraisal provides details such as name, description, media format, whether the records and information are vital, and how they’re used.

The objective of the appraisal is to provide a mechanism for companies to identify the records and information they possess to know how long to keep them as well as how to manage them during their life cycle. The absence of an appraisal creates an ad hoc and decentralized environment in which employees, out of necessity, make individual or departmental decisions regarding the management of their records and information.

Preparing for the Appraisal

Whether you’re a small-business owner or work for a large corporation, if the decision has been made to appraise your records and information, you will need to properly prepare. Several major appraisal elements need to be considered, such as the underlying methodology for an appraisal, its degree of comprehensiveness, communicating the appraisal plan to management, and its scheduling.

Push for the purge

Regardless of the appraisal approach you choose, the organization will have to dedicate time, resources, and planning to make it a success. Each appraisal approach requires evaluating a significant amount of information. The less information you have to evaluate, the quicker the process can be completed.

One way to reduce the amount of information that needs to be evaluated is to pare it down prior to the appraisal. It is estimated that more than 50 percent of the paper and electronic information that organizations currently store doesn’t have any business value and can be immediately discarded. You can eliminate what you no longer need by conducting a preliminary file purge (purge).

A purge is conducted to eliminate unneeded nonrecord content in preparation for an appraisal. A purge may be conducted on a company-wide basis or department by department, based on your appraisal schedule. A purge will help reduce the amount of content that has to be appraised, and also provides a benefit to the company by reducing storage needs and costs, allowing employees to find the information they need in a more efficient manner.

If you decide upon a comprehensive appraisal approach (which is recommended), the purge should include the destruction and deletion of both paper documents and electronic files. This includes paper documents in all file cabinets and electronic files on all computers.

Don’t forget the hard drives

The objective of purging electronic content is the same as for paper — get rid of what you know longer need. However, how you accomplish this is significantly different. Purging electronic content requires employees to review electronic folders and files on hard drives and network drives as well as information residing on portable media such as CDs, USB drives, and so on. The following types of electronic information are examples of items that need to be reviewed during the purge process:

E-mails

E-mails

Word, Excel, and PowerPoint documents

Word, Excel, and PowerPoint documents

Collaboration site content (for example, Microsoft SharePoint)

Collaboration site content (for example, Microsoft SharePoint)

PDF files

PDF files

All graphics files, such as TIFFs, JPEGs, PNGs, and BMPs

All graphics files, such as TIFFs, JPEGs, PNGs, and BMPs

Audio and video files

Audio and video files

Note: The electronic information listed here represents unstructured information. Appraising structured (software system data) information is covered in Chapter 16.

Although the volume of electronic content belonging to a department may dwarf what they have in their file cabinets, computers can provide assistance to help manage that content. When you access a particular drive, your computer provides a Date Modified column. (See Figure 2-1.) Modified here means the last time any changes were made to the file and then saved. Computers allow you to sort folders and files in this column by date. Note: The Date Modified field of some file types such as .mdb (Microsoft Access Database) files may change upon viewing instead of when actually modified by the user.

Date Modified is a great starting point for determining whether electronic information is still relevant. If you sort by most recent date first, this information probably still needs to be retained. On the flip side, if you haven’t modified your oldest files in several years, an increased probability exists that the file is eligible to be deleted. However, neither scenario is a guarantee. Employees still need to review all files to ensure their status.

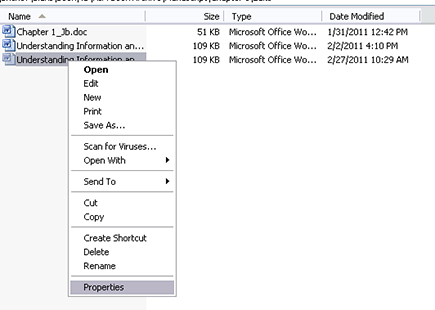

Another strategy in helping employees make a decision to either retain or delete a file involves examining the Created date and/or Accessed date of a file. The Created date provides the creation date of the file. The Accessed date indicates the last time anyone accessed or reviewed the file. If you right-click the file you want to review, the contextual menu shown in Figure 2-2 appears.

Figure 2-2: Properties.

Select Properties from the contextual menu to review the Created and Accessed date, as shown in Figure 2-3.

Figure 2-3: Created and Accessed date.

Choosing an Appraisal Method

The appraisal method you choose will lay the foundation for the organization’s records and information retention schedule and overall program. Therefore, it’s extremely important to prepare for the appraisal process and research the options.

A method to the madness

You find two main appraisal concepts — departmental and functional. Each approach has upsides and issues to consider. The record series method represents the traditional approach used by many organizations. The functional method is a relatively new concept now in use by many governmental agencies and gaining momentum in private industry:

Departmental: The focus of the record series appraisal method primarily concentrates on each record series type that a department possesses, with minimal concern as to how the record types are used or what department functions they help facilitate. The record series method ultimately results in each record type being listed individually, by department, on the organization’s record retention schedule.

Departmental: The focus of the record series appraisal method primarily concentrates on each record series type that a department possesses, with minimal concern as to how the record types are used or what department functions they help facilitate. The record series method ultimately results in each record type being listed individually, by department, on the organization’s record retention schedule.

Functional: The functional appraisal approach focuses on appraising departmental functions rather than appraising individual record or document types. This method is based on the premise that each record series is part of a function. In this case, all record types that support an individual process will be grouped together for retention purposes.

Functional: The functional appraisal approach focuses on appraising departmental functions rather than appraising individual record or document types. This method is based on the premise that each record series is part of a function. In this case, all record types that support an individual process will be grouped together for retention purposes.

For example, the Accounts Payable department is responsible for paying vendor invoices. The process involves several different record types — purchase orders, packing lists, invoices, and remittances, for example. The record series appraisal method looks at each of these records in an individual manner. Each will be appraised separately and each listed on the organization’s record retention schedule under Accounts Payable.

The functional appraisal approach views these records in a macro or conglomerate fashion. All the records support the Accounts Payable function. Therefore, the retention schedule will reflect the function, such as “payables,” not the individual records.

The good and the . . . good

Both appraisal methods should be researched before choosing which one to incorporate into your company. The research and decision process should be a group effort, including at a minimum the department that owns the information, as well as the Legal, Compliance, and Tax departments. The following is a guide to help you understand how each approach may impact your company:

Departmental:

Departmental:

• The appraisal will take more time to complete because you are evaluating each record series.

• Will increase the number of entries on the record retention schedule because you are accounting for each record series.

• Provides the organization with the ability to manage the life cycle of individual records.

• Provides the ability to place information hold orders on a specific record series instead of placing a hold on a group of records that possibly aren’t relevant to the matter, causing records to be held that may otherwise be eligible to be destroyed or deleted.

• Can provide a better and quicker understanding of the individual record types a department possesses, versus all records that are applicable to a function being labeled with a function name such as “payables.”

• The process of approving records and information for destruction or deletion may take longer due to the approvers having to review individual records rather than groups of related records.

• Subsequent filing and retrieval of records and information may take longer due to having to file at the individual record series level instead of filing at the functional level.

Functional:

Functional:

• Expedites the appraisal process by eliminating the need to evaluate individual record types and allowing you to focus instead on the records that are part of a function as a group.

• Will ultimately reduce the time spent by employees deciding how to classify, file, and retrieve records and information because they are accounted for at the aggregate level.

• When grouping records that are part of a function together for retention purposes, the possibility increases that you will keep some function-related records longer than they need to be retained. For example, an invoice needs to be retained for seven years; however, the packing slip related to the Accounts Payable process may only need to be kept for one year.

• Without additional available documentation, it can reduce the organization’s ability to identify specific record types that departments have and use because the records are not individually listed on the retention schedule.

• Allows the company to obtain a better understanding of what records facilitate the processing of functions.

• Expedites the destruction and deletion approval process because the approvers don’t have to review individual record and information types.

• Reduces the number of line items on the retention schedule, making it more efficient to use.

• Information hold orders have to be placed on a group of functional records rather than at an individual record series level, resulting in the possibility of retaining some related records longer than they are needed.

Volume: Although volume shouldn’t necessarily be a deciding factor in the method you choose, realistically it does play a part. Some companies have started out to complete a departmental appraisal, but found they became bogged down in the process due to the extremely large amount of information they had to appraise. The rationale to move to the functional approach was based on the fact that even though they wanted to account for every record series individually rather than functionally, they were concerned that the process would stall and resources would dry up and leave them with an incomplete appraisal.

Volume: Although volume shouldn’t necessarily be a deciding factor in the method you choose, realistically it does play a part. Some companies have started out to complete a departmental appraisal, but found they became bogged down in the process due to the extremely large amount of information they had to appraise. The rationale to move to the functional approach was based on the fact that even though they wanted to account for every record series individually rather than functionally, they were concerned that the process would stall and resources would dry up and leave them with an incomplete appraisal.

Regulatory requirements: If your organization operates in a highly regulated industry such as nuclear energy, pharmaceuticals, or tobacco, you need to determine whether any regulatory requirements would prevent or dissuade your company from using either appraisal approach. Organizations operating in a highly regulated industry may prefer to conduct a departmental appraisal, which allows them to manage the record life cycle at the departmental level, even if they have a significant amount of volume to appraise.

Regulatory requirements: If your organization operates in a highly regulated industry such as nuclear energy, pharmaceuticals, or tobacco, you need to determine whether any regulatory requirements would prevent or dissuade your company from using either appraisal approach. Organizations operating in a highly regulated industry may prefer to conduct a departmental appraisal, which allows them to manage the record life cycle at the departmental level, even if they have a significant amount of volume to appraise.

Litigation: It is recommended that your legal department or attorneys issue an opinion on which appraisal method they feel provides the best defensible legal position for the organization. For example, a functional approach lumps records related to the same function together and may ultimately result in less information being captured about individual record types and some records being retained longer than required by law or regulatory entities. A functional appraisal may make it difficult during a lawsuit to determine what specific records may be involved. In addition, during a lawsuit, audit, or governmental inquiry, you may have to produce information that should already have been destroyed that proves damaging. If an organization feels that the legal risks are too great, it may decide to pursue the departmental appraisal approach, even if it has a significant amount of volume to appraise.

Litigation: It is recommended that your legal department or attorneys issue an opinion on which appraisal method they feel provides the best defensible legal position for the organization. For example, a functional approach lumps records related to the same function together and may ultimately result in less information being captured about individual record types and some records being retained longer than required by law or regulatory entities. A functional appraisal may make it difficult during a lawsuit to determine what specific records may be involved. In addition, during a lawsuit, audit, or governmental inquiry, you may have to produce information that should already have been destroyed that proves damaging. If an organization feels that the legal risks are too great, it may decide to pursue the departmental appraisal approach, even if it has a significant amount of volume to appraise.

Conducting the Appraisal

After your organization has decided which appraisal method to use, it’s time to plan the process. Planning is the key to a successful appraisal. It includes items such as determining how the information will be captured, letting all participating parties know what it is expected of them, conducting preappraisal department visits, and figuring out what to do with the information after you have it.

The following sections provide you with the knowledge and tools you need to conduct the appraisal. You find out what options exist for capturing appraisal information and see an example of forms that can be used to document the process.

Capturing appraisal information

Once again you have options! You have three primary methods to choose from for capturing appraisal information:

Inventory

Inventory

Interview

Interview

Questionnaire

Questionnaire

Each option can be used to capture appraisal information regardless of the appraisal method (departmental or functional) that your organization is pursuing. However, each approach has distinct advantages and disadvantages that need to be considered before proceeding with the appraisal.

Taking inventory

The inventory appraisal method is the most time consuming (for the department, you, and your staff) and labor intensive of the options, but it provides the most accurate results. This approach requires an in-depth review of a department’s records and information.

If you are conducting a departmental appraisal, this approach involves opening every file cabinet and desk drawer, as well as accessing employees’ computers. During the process, your goal is to document a department’s content at the folder level, not the document level.

The following list provides guidance on how to inventory paper and electronic information at the folder level:

For example, if you open a file cabinet drawer and see a lot of hanging folders, you can assume that each document in the same folder is related. You don’t have to account for every document, but you do need to note the hanging folder and the type of information it contains.

For example, if you open a file cabinet drawer and see a lot of hanging folders, you can assume that each document in the same folder is related. You don’t have to account for every document, but you do need to note the hanging folder and the type of information it contains.

The same is true for electronic content — not each file, but each main computer folder. If a computer folder is labeled Invoices, you don’t have to go through it to make sure that all the items in the folder are in fact invoices.

The same is true for electronic content — not each file, but each main computer folder. If a computer folder is labeled Invoices, you don’t have to go through it to make sure that all the items in the folder are in fact invoices.

If you are conducting a functional appraisal, the method is different. Instead of focusing your initial efforts on documenting the department’s individual record types, you start by obtaining an understanding of the department’s functions and documenting their processes and workflows. After you have captured this information, you work backward to identify the record types used to support each function.

An effective functional appraisal is comprised of the following items:

For example, you first want to sit down with management and employees from the department you are appraising and ask them to list and describe the functions they are responsible for performing.

For example, you first want to sit down with management and employees from the department you are appraising and ask them to list and describe the functions they are responsible for performing.

After the list is complete, you work with departmental employees to determine what individual record types are part of a functional series.

After the list is complete, you work with departmental employees to determine what individual record types are part of a functional series.

Going through with an interview

The interview appraisal method involves meeting with management and knowledgeable employees from each department and asking them a series of questions in an effort to appraise their records and information. This approach doesn’t require you to open file cabinet drawers and computer folders, resulting in a quicker but less accurate and detailed appraisal. However, with proper planning, the interview option can still be effective, and it will allow you to account for most of your company’s records, information, and functions.

Your challenge during the interview is to get employees to think about the total population of their records and information — to make sure that you capture as much of it as possible during the appraisal process. Get them to think about the out-of-sight, out-of-mind records and information. This may take some gentle prodding. File cabinets full of documents are easy targets. It’s the paper records they have boxed up and sent to storage, and the thousands of computer files on their hard drives and network drives, that employees don’t think about during the interview process.

If you are conducting a functional appraisal, you need to focus your initial interview questions on the department’s functions. Then move on to questions about the records and information used to process the functions. A lack of understanding of a department’s processes will make it difficult to identify the records that are part of the function.

Quizzing with a questionnaire

The questionnaire method takes the least amount of time to complete, but it is the least comprehensive of the appraisal options. When using the questionnaire method, you provide managers with a set of questions and simply rely on them (or their staff) to document their record and information types and functions and how they interact. Unlike the inventory and interview methods, you’ll not be in the department to assist in the gathering of the information.

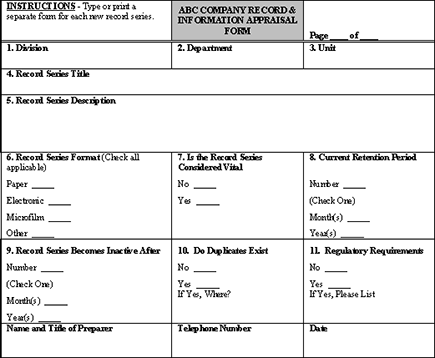

Documenting the appraisal

After you decide how the appraisal will be conducted, you have to determine how to document your findings. Appraisal forms are used to capture pertinent information. The form format and questions will vary depending on the appraisal method — departmental or functional.

When conducting a departmental appraisal, the same form can be used for inventory, interview, and questionnaire approaches. The form should be constructed so that it’s easy to understand and complete regardless of who is filling it out. When using the questionnaire approach, it’s recommended that you create an instruction page that provides guidance on completing the form.

Prior to conducting the appraisal, you should have a kickoff meeting with the department employees to communicate what will be involved in the process and what their roles and responsibilities will be. The meeting can give employees an opportunity to ask questions and raise concerns.

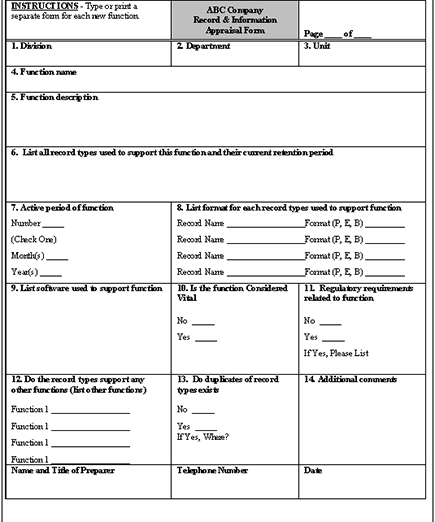

The form for the functional appraisal is different from the form used for departmental appraisals. The functional appraisal form leaves room for the listing of functions and their related records. When conducting the functional appraisal, the same form can be used for the inventory, interview, and questionnaire approaches. Again, when using the questionnaire approach, it’s recommended that you create an instruction page that provides guidance on completing the form.

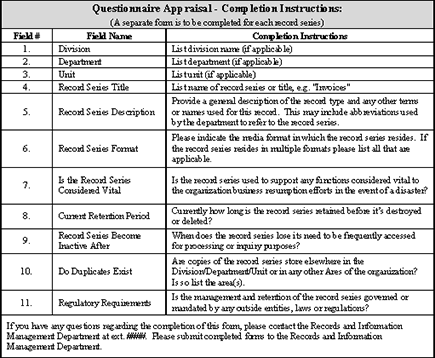

Figures 2-4, 2-5, and 2-6 show examples of appraisal forms that you can use for the departmental and functional methods, as well as an example of a questionnaire instruction page.

Figure 2-4: Departmental appraisal form.

Figure 2-4 is an example of a departmental appraisal form. The form focuses on the individual record series and their characteristics such as the format (paper or electronic) and whether they are considered vital and are governed by any regulations.

The functional appraisal form focuses on the departmental function or process first, including a description of the function, and then focuses on what records are used to perform the function.

If the organization has made the decision to proceed with a questionnaire appraisal, the following instruction page example (record series appraisal) can provide the guidance needed to ensure that it’s accurately filled out by departmental or agency personnel. The same approach can be used for the functional appraisal. The questionnaire is designed to be convenient and easy to understand and complete.

Figure 2-5: Functional appraisal form.

Figure 2-6: Questionnaire appraisal instruction form (departmental).

Processing the appraisal results

After the appraisals have been completed, the fun starts! The appraisals need to be reviewed for errors and omissions. During this time, follow-up visits or phone calls may need to take place with departments to ensure that the appraisal information is as accurate and comprehensive as possible. The next step is to begin conducting research of the appraisal information to develop the organization’s retention schedules. In the next chapter, I tackle everything associated with creating and implementing a records retention schedule.

Different appraisal methodologies and options produce different results, so it’s important to understand the premise and nature of each alternative to determine which approach best fits your organizational objectives. This chapter provides the information you need to make the appropriate decision.

Different appraisal methodologies and options produce different results, so it’s important to understand the premise and nature of each alternative to determine which approach best fits your organizational objectives. This chapter provides the information you need to make the appropriate decision. Prior to conducting a purge, it’s extremely important to clearly communicate to everyone who is participating not to destroy information that could possibly be records during the event. The purge should focus on cleaning out unneeded duplicate copies of information, supplies, and items that should not be in the filing system. You shouldn’t purge any information that is part of an active or potential lawsuit or government inquiry. The primary types of information that should be discarded during the purge are copies of records and nonrecords that are no longer needed, nonrecord information that no longer has any business value, and content that never had business value — junk.

Prior to conducting a purge, it’s extremely important to clearly communicate to everyone who is participating not to destroy information that could possibly be records during the event. The purge should focus on cleaning out unneeded duplicate copies of information, supplies, and items that should not be in the filing system. You shouldn’t purge any information that is part of an active or potential lawsuit or government inquiry. The primary types of information that should be discarded during the purge are copies of records and nonrecords that are no longer needed, nonrecord information that no longer has any business value, and content that never had business value — junk. In preparation for the purge, it’s a good idea to reach out to the management staff of the participating departments to discuss the process — be sure to highlight what they can expect and provide an opportunity for them to ask questions. During the discussion, you may want to make the recommendation that they assign a departmental “point person” who can be your liaison during the purge itself. This approach provides a knowledgeable person who can funnel all departmental purge questions to you.

In preparation for the purge, it’s a good idea to reach out to the management staff of the participating departments to discuss the process — be sure to highlight what they can expect and provide an opportunity for them to ask questions. During the discussion, you may want to make the recommendation that they assign a departmental “point person” who can be your liaison during the purge itself. This approach provides a knowledgeable person who can funnel all departmental purge questions to you.