Chapter 7

Watch Out, I’m Backing Up

In This Chapter

Identifying backup types

Identifying backup types

Understanding backup tape risks

Understanding backup tape risks

Applying records management principles to backed-up data

Applying records management principles to backed-up data

Most of us have experienced the frustration and panic of working on a spreadsheet or document when suddenly the computer freezes and the “blue screen of death” appears — you are immediately brought face to face with the realization that you are the victim of a crash. Or perhaps you’ve experienced disaster on an even larger scale, where you have been part of a department that was unable to log in to a critical business software application because the server crashed. It’s times like these when backups can make the difference between recovering information in a short period of time and being able to resume normal business operations, or saying farewell to the information forever.

In this chapter, you look closer into what backups actually are, as well as analyze the different types of backups and their purpose. In addition, you find out how to best manage backups in an effort to ensure that they complement your records and information management program instead of becoming its nemesis.

Creating a Backup Plan

Every business, regardless of size, needs to routinely back up the information stored on its computers and servers. A backup is the process of transferring data from your computer systems to another storage device, with the objective of being able to restore the information in the event of data loss. Information in this case typically consists of structured (database) and unstructured (images, documents, and spreadsheets) data.

You have a number of different options for conducting backups, including what, when, and where to back up. The following sections cover each of these topics and provide the knowledge you need to ensure that your data is safe, accurate, and accessible.

Identifying different types of backups

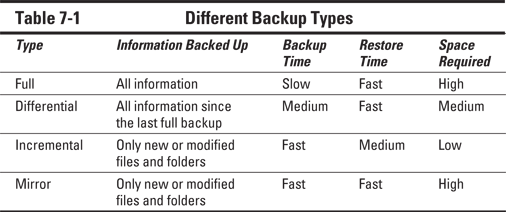

It is critical to have a backup strategy, whether it’s for the one computer you use for your small business or for the hundreds of servers your company has in a data center. Understanding the types of backups that can be conducted can help you determine what data you need to duplicate in the event of data loss. Listed as follows (and summarized in Table 7-1) are four types of backups that can be used by organizations of all sizes:

Full: This type of backup makes a copy of all the data in all files and folders. Conducting frequent full backups allows a faster and simpler restore.

Full: This type of backup makes a copy of all the data in all files and folders. Conducting frequent full backups allows a faster and simpler restore.

Differential: A differential backup makes a copy of all data that has changed since the last full backup. Differential backups provide a fast restore. However, if differential backups are conducted too frequently, this can cause the size of the backup file to grow very large because it includes information from previous differential backups. In some cases, this can create a differential backup file that’s larger than a full backup file.

Differential: A differential backup makes a copy of all data that has changed since the last full backup. Differential backups provide a fast restore. However, if differential backups are conducted too frequently, this can cause the size of the backup file to grow very large because it includes information from previous differential backups. In some cases, this can create a differential backup file that’s larger than a full backup file.

Incremental: This type of backup makes a copy of all data that has been modified since the last full or differential backup. An incremental backup takes the least amount of time to complete, but it can take longer to restore due to each individual incremental backup having to be processed.

Incremental: This type of backup makes a copy of all data that has been modified since the last full or differential backup. An incremental backup takes the least amount of time to complete, but it can take longer to restore due to each individual incremental backup having to be processed.

Mirror: A mirror backup is similar to a full backup with a few twists. The first time a mirror backup runs, it will back up all information. However, subsequent backups only make a copy of information that has changed or been modified. Mirror backups are not compressed or encrypted. Users are able to point to the backup location and quickly access the backed-up data.

Mirror: A mirror backup is similar to a full backup with a few twists. The first time a mirror backup runs, it will back up all information. However, subsequent backups only make a copy of information that has changed or been modified. Mirror backups are not compressed or encrypted. Users are able to point to the backup location and quickly access the backed-up data.

Small businesses need to conduct full backups on a regular basis. This approach is feasible due to the limited amount of information that has to be backed up. Backing up your computer can be performed manually or on an automatic scheduled basis.

What works for small businesses, however, may not be manageable for medium to large organizations. Due to the extreme amount of data that these organizations possess, conducting full backups is more challenging. Companies have to dedicate staff, software, and other resources to developing, implementing, and maintaining a formal backup process.

The IT departments of large organizations typically conduct backups during nonpeak times (late at night and early morning) to ensure that all systems are operable and accessible during normal business hours. Most IT departments schedule different types of backups to be conducted throughout the week or month. As an example, this may include differential or incremental backups each night and a full backup at the end of each week.

Based on the significant volume of data that large organizations are required to back up and retain, the organizations are continuously evaluating new techniques, media, and applications to shorten backup times. Later in this chapter, you get a chance to see how you can apply records and information management principles to backups to help better manage the process.

Finding a place to back up

An important piece of the backup puzzle is determining a target location for your backed-up files. The amount of data your company possesses normally determines what medium you need to use for backups:

Magnetic tape: Tapes are most commonly used by organizations that have a large amount of data to back up. Tapes are usually housed in cartridges or cassettes. Data is written to tapes and read by a tape drive. For years, this backup option has proven the most economical for backing up large amounts of information. A benefit of magnetic tapes is that they can be reused. Data centers create tape rotation schedules that allow tapes, after a prescribed period of time, to be overwritten with new data.

Magnetic tape: Tapes are most commonly used by organizations that have a large amount of data to back up. Tapes are usually housed in cartridges or cassettes. Data is written to tapes and read by a tape drive. For years, this backup option has proven the most economical for backing up large amounts of information. A benefit of magnetic tapes is that they can be reused. Data centers create tape rotation schedules that allow tapes, after a prescribed period of time, to be overwritten with new data.

External hard drive: For many years, it wasn’t cost effective to back up large amounts of data to an external hard drive. However, the cost of drives has significantly decreased and is now comparable to magnetic tapes. Hard drives allow more flexibility than tapes, such as no winding or rewinding to locate information — meaning faster restore capability — and instant rewrite capability, because you don’t have to deal with the erase cycle that comes with tapes.

External hard drive: For many years, it wasn’t cost effective to back up large amounts of data to an external hard drive. However, the cost of drives has significantly decreased and is now comparable to magnetic tapes. Hard drives allow more flexibility than tapes, such as no winding or rewinding to locate information — meaning faster restore capability — and instant rewrite capability, because you don’t have to deal with the erase cycle that comes with tapes.

Optical disc: Optical media refers to recordable and rewriteable CDs and DVDs. Optical discs don’t have the storage capacity of tapes or external hard drives and normally are only used to back up selected files rather than to perform full system backups. Still, optical discs are economical and simple to use. Most computers are now equipped with CD and DVD burners that allow you to drag and drop files to the Disc icon and record the data. This is a great backup option for small- and medium-sized businesses.

Optical disc: Optical media refers to recordable and rewriteable CDs and DVDs. Optical discs don’t have the storage capacity of tapes or external hard drives and normally are only used to back up selected files rather than to perform full system backups. Still, optical discs are economical and simple to use. Most computers are now equipped with CD and DVD burners that allow you to drag and drop files to the Disc icon and record the data. This is a great backup option for small- and medium-sized businesses.

Flash drive: Over the past several years, flash drive storage capacity has significantly increased. Today, most flash drives have several gigabytes (GB) of capacity and are rewriteable, making them a good option for backing up selected files. The flash drive shows as an additional drive on your computer. It is a very portable medium and can be used to move data between computers. Some flash drives can be password-protected and encrypted.

Flash drive: Over the past several years, flash drive storage capacity has significantly increased. Today, most flash drives have several gigabytes (GB) of capacity and are rewriteable, making them a good option for backing up selected files. The flash drive shows as an additional drive on your computer. It is a very portable medium and can be used to move data between computers. Some flash drives can be password-protected and encrypted.

Even though flash drives can have significant storage capacity, and now contain encryption capability, most large organizations haven’t adopted the use of flash drives for routine data backups. This is mainly due to the typical flash drive not having the storage capacity of disk drives or magnetic tapes, as well as being easy to lose based on their compact size. However, they are a good option for small- to medium-sized businesses.

Cloud: The cloud refers to an Internet-based vendor-hosted or software as a service (SaaS) operating environment. As cloud computing has matured, the cost has decreased, and it is now becoming a viable option for small- and medium-sized businesses. Cloud backups are performed by transmitting data to a vendor’s site via the Internet. However, if your organization is using the cloud for processing and other computer services, your information is most likely being backed up on a regular basis by the vendor. (For more on the potential of the cloud, check out Chapter 16.)

Cloud: The cloud refers to an Internet-based vendor-hosted or software as a service (SaaS) operating environment. As cloud computing has matured, the cost has decreased, and it is now becoming a viable option for small- and medium-sized businesses. Cloud backups are performed by transmitting data to a vendor’s site via the Internet. However, if your organization is using the cloud for processing and other computer services, your information is most likely being backed up on a regular basis by the vendor. (For more on the potential of the cloud, check out Chapter 16.)

Distinguishing between backups and archives

Over the past decade, organizations have seen a dramatic increase in laws and regulations that impact corporate behavior, including the management of their information. Many of the laws and regulations that have been enacted require companies to retain their records (both paper and electronic) for specified time frames, to destroy the records after the time frame expires, and to ensure that the information is quickly accessible. Backing up to magnetic tapes — as most large organizations do — doesn’t provide this capability because of the difficulty and operational inefficiencies related to deleting specific files from a tape after their retention period has expired.

While backup solutions provide data protection and recovery, data archiving provides efficient retrieval and retention, as well as the capability to meet the organization’s regulatory, legal, and historical needs. Several media can be used for digital archiving, such as optical discs, hard drives, CDs, DVDs, and digital tapes. Although these preferred digital archiving storage options exist, the reality is that most organizations continue to store information required for regulatory, legal, and historical purposes on magnetic tape. Magnetic tape is not a good archiving medium for records whose retention must be managed. Magnetic tape is an “all-or-nothing” format. Magnetic tape doesn’t provide the ability to delete specific files. If a magnetic tape contains various types of records with different retention periods, you must restore the tape to a disk and then delete the files whose retention period has expired. You then back up the remaining records to the tape again.

Archiving is a dynamic process. This means that new data will continuously be added to the archive. Therefore, because magnetic tape doesn’t allow an organization to properly manage the retention of archived data, you should use a media format such as disk to archive your information. It’s recommended that all information be evaluated prior to being archived. The evaluation process should be formalized and conducted by a knowledgeable business department representative, the records manager, and IT. For example, if the Workers’ Compensation department is implementing a new administrative software application, certain data from the system probably needs to be retained for a specified length of time. The business unit, records manager, and IT should confer to determine what information needs to be archived and for how long. In the absence of an evaluation process, erroneous data could be archived or applicable data may be archived, but for an inappropriate time frame.

The tale of the mystery tape

Information accumulation breeds risk. Over time, organizational information accumulates in file cabinets, in desk drawers, on hard drives, and on network drives — and also on backup tapes! Although backing up company data is vital for resuming business operations and reducing risks, if not properly managed, it can be a source for a whole other set of risks. The following sections analyze the types of risks associated with data stored on backup tapes.

Yes, you may end up using different media to back up your data, but the vast majority of organizations still rely on magnetic tapes to handle their backup chores. Even if companies are using disks for backups, they probably still have legacy magnetic tapes in storage. It’s not unusual for medium- to large-sized companies to have accumulated tens or hundreds of thousands of tapes over the years. The issue is that most organizations don’t know what information is contained on the tapes.

Although magnetic tape cartridges are labeled, organizations rely upon employees to label the cartridges in a manner that allows a clear understanding of the contents of the tape. If the labeling is cryptic or fades over time, it can make it extremely difficult to decipher the contents.

For many years, organizations and their IT departments didn’t have to worry much about accessing data stored on backup tapes. Aside from the occasional request to restore an employee’s e-mail or other miscellaneous data, backup tapes sat idle in storage. Historically, retrieving specific information from magnetic tapes has not been easy. Digital storage mechanisms allow an employee to search and retrieve targeted information. However, magnetic tapes require users to scroll through the contents of the tape until they locate what they need. Although this approach isn’t efficient, in years past, the volume and types of restore requests were manageable.

Organizations are now faced with increasing numbers of lawsuits and regulations that require access to and production of company information. A decade ago, most organizations weren’t too concerned about having to produce information for a lawsuit or governmental inquiry from their backup tapes; they could invoke the burden argument. The burden argument is a claim that it’s too cost prohibitive and burdensome to restore, search, and retrieve content from backup tapes. Times and technology have changed, however, poking holes in this argument. New technologies now make it affordable and viable for information from backup tapes to be produced.

The primary difficulty in producing information from backup tapes for a lawsuit involved organizations converting from one backup system application to another. To restore older tapes, a company needed access to the previous backup system application. If the application was no longer available, the company would have to send the tapes to a third party to be restored. However, new technologies allow tape data to be restored without having access to the previous backup operating environment.

Judges and lawyers are becoming more educated and savvy about electronically stored information (ESI) and related technologies. They understand what is feasible and what isn’t. The result is that organizations are now faced with searching huge volumes of backed-up data to properly respond to discovery requests.

Managing Backups

As digital information continues to grow at an astounding rate, IT departments are looking for guidance on how to manage the volume. Information Technology personnel are now frequently conferring with records managers in an attempt to apply life cycle principles to electronic data.

Applying records and information management principles can help control the accumulation of electronic data, make information easier to identify and retrieve, and ensure that it’s appropriately deleted. In the following sections, you discover how to apply these principles so that you only back up what is needed, know how to determine the retention period of data backups, and have a strategy in place so that you can clean up what’s accumulated over the years.

Determining what needs to be backed up

Prior to the events of September 11, 2001, most IT departments acted independently when determining what should be backed up and how frequently it should be backed up. After 9/11, organizations across the world quickly realized that their companies were not adequately prepared to resume business operations in the aftermath of a catastrophic event. This resulted in business continuity planning (BCP). The purpose of BCP was to formulate a partnership between business departments and IT in an effort to identify and protect critical operating information that must be accessible within a specified time frame after a disaster to resume business operations. This process was the start of records managers and IT personnel working together to assist business areas in managing their information. If your organization hasn’t yet forged the partnership between records management and IT, the organization should begin taking the steps to do so.

Criticality: How important or sensitive is the information? Critical information typically includes, but isn’t limited to, data related to the organization’s accounting, human resources, and customer applications.

Criticality: How important or sensitive is the information? Critical information typically includes, but isn’t limited to, data related to the organization’s accounting, human resources, and customer applications.

Legal: Could the information be important in the event of a lawsuit? Legal departments understand what types of information are considered high risk and should be backed up or archived for long-term storage.

Legal: Could the information be important in the event of a lawsuit? Legal departments understand what types of information are considered high risk and should be backed up or archived for long-term storage.

Regulatory: Is the information required to be backed up, retained, and accessible based on regulatory requirements? Organizations should ensure that they are familiar with regulations that govern their operating environment, and back up or archive associated information for the prescribed time frame.

Regulatory: Is the information required to be backed up, retained, and accessible based on regulatory requirements? Organizations should ensure that they are familiar with regulations that govern their operating environment, and back up or archive associated information for the prescribed time frame.

Historical: What information should be retained that has historical significance? Most companies have accumulated information over the years — press clippings and photos, for example — that serve as evidence of the organization’s existence.

Historical: What information should be retained that has historical significance? Most companies have accumulated information over the years — press clippings and photos, for example — that serve as evidence of the organization’s existence.

Applying retention to backups

Restore: This type of backup ensures that information can be restored and accessed in the event of a system failure.

Restore: This type of backup ensures that information can be restored and accessed in the event of a system failure.

Disaster recovery: Disaster recovery backups encompass predetermined information related to critical systems and files that are needed to resume operations after a disaster or catastrophic event.

Disaster recovery: Disaster recovery backups encompass predetermined information related to critical systems and files that are needed to resume operations after a disaster or catastrophic event.

Archives: Archiving ensures that information that must be retained for legal, regulatory, or historical purposes are backed up.

Archives: Archiving ensures that information that must be retained for legal, regulatory, or historical purposes are backed up.

Restore and disaster recovery backups are typically overwritten based on a tape rotation schedule. However, archive backups are used for retaining records that must be kept in accordance with operational, legal, and regulatory purposes and should be deleted when their retention period has expired. Archived records aren’t routinely overwritten like disaster recovery backup tapes are. The focus of this section is how to apply appraisal and retention periods to archive backups.

When determining how long to keep archived information, start with the retention schedule that you have already developed, even if the current schedule only addresses paper records. In many cases, you will find that you have already evaluated and assigned a retention period to physical information that is related to or is the same as its electronic counterpart. For example, you may have assigned a seven-year retention period to paper contracts, but you also have electronic contracts that are archived. The same retention period should be assigned to the electronic versions.

Creating a data retention schedule

Archived information consists of unstructured and structured data. Examples of unstructured data are documents, spreadsheets, images, PDFs, and e-mails. Structured data is information based on data fields, such as a database table in a software application.

Most companies are familiar with the concept of record retention schedules. Such schedules get used when managing the length of time you keep paper records such as invoices, employee files, and contracts. A smaller number of organizations utilize this same approach for unstructured electronic records and information. Then a small percentage of companies exist that have addressed the need to apply retention principles to structured data.

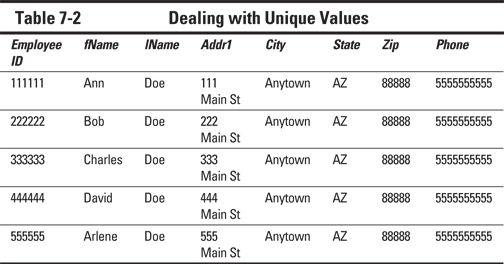

For most organizations, backing up and retaining structured information from software applications account for the majority of backed-up volume. Applying retention periods to structured data is a relatively new concept that is getting a lot of attention. Structured data poses some philosophical records management issues. To see what I mean, check out Table 7-2, which contains numerous fields of information with unique values. The question here is, does each individual value or data element — say, someone’s first name — by itself constitute a record? Some say yes, and some say no.

As the debate has progressed, more records managers have come to the conclusion that a data field in and of itself is not a record, but when it’s combined with other related data fields through the software application, a record is born. For example, if you image a vendor invoice, it creates a digital replication of the document that can be viewed and understood. However, the individual data elements represented on the document, such as vendor name, number, and address, also exist in your organization’s accounting system database in separate fields. If you view an individual data element in a field, it doesn’t have much meaning, but when the software application brings all the associated elements together to form the invoice, it now has meaning.

To apply retention to structured information, you can use the same appraisal method used for unstructured and physical content. If you retain paper invoices for seven years, the structured information in the accounting system that relates to invoices should also be retained for seven years.

Appraising structured information is a group effort. The appraisal allows you to understand the nature of a software application, see who uses it, determine where the application’s information resides on the network as well as what data it produces, let you establish what information should be archived, and set up the required retention periods. Each department that uses an application should be involved in the appraisal along with the Records Management and IT departments.

Deleting backed-up and archived information

The thought of deleting records and information makes some people cringe, but don’t fear. It’s all part of the information life cycle and should take place on a regular and scheduled basis — as long as the necessary homework has been done, meaning that the information has been researched and the appropriate retention periods have been assigned.

As you discovered, magnetic tapes are still widely used for system and file restores, disaster recovery, and archive backups. Although tapes used for basic recovery and disaster recovery are erased and overwritten on a scheduled basis, archive tapes aren’t; this poses a significant retention and deletion issue. Magnetic tapes don’t allow you to delete or erase specific files — it’s an all-or-nothing proposition when deleting content on backup tapes.

As you read in the preceding sections, backups are performed to prevent data loss in the event that your computer crashes or your files become corrupt. Backups of this type are not meant for the long-term storage of organizational information that must be retained in accordance with the company’s records and information retention schedules. This is the role and purpose of

As you read in the preceding sections, backups are performed to prevent data loss in the event that your computer crashes or your files become corrupt. Backups of this type are not meant for the long-term storage of organizational information that must be retained in accordance with the company’s records and information retention schedules. This is the role and purpose of  If your organization is considering the creation of digital archives, it’s important to plan ahead. Prior to creating an archive, you should first analyze and determine what data needs to be captured, how long it needs to be retained, and how frequently it will be accessed during its life cycle. After these details have been sorted out, the next step is to work with your IT department to determine the storage device that best meets your company’s needs.

If your organization is considering the creation of digital archives, it’s important to plan ahead. Prior to creating an archive, you should first analyze and determine what data needs to be captured, how long it needs to be retained, and how frequently it will be accessed during its life cycle. After these details have been sorted out, the next step is to work with your IT department to determine the storage device that best meets your company’s needs. The cost to search and produce information from backup tapes can be significant. However, the primary risk of not managing backup tapes is the potential for judgments, fines, and penalties associated with information on backup tapes that proves to be a liability. Applying records and information management principles to tape backups can help reduce the risks.

The cost to search and produce information from backup tapes can be significant. However, the primary risk of not managing backup tapes is the potential for judgments, fines, and penalties associated with information on backup tapes that proves to be a liability. Applying records and information management principles to tape backups can help reduce the risks.