Part II

The Initial Expansion

(6–12)

With the characterization of the earliest Jerusalem church satisfactorily rounded off — not least its Jesus focus and Spirit empowerment, and the continuity symbolized by the Temple, despite the hostility of the Temple authorities — Luke was ready to describe the next phase of Christian beginnings. Here also the structure of this next major section of Luke’s account is quite deliberate. It recounts the circumstances which resulted in the initial expansion of the Jesus movement out from the beginnings in Jerusalem and how the first stages in that expansion began to transform the self-understanding of the new movement which had so far prevailed. Particularly striking is the tension running through the ordering of events between continuity with Jerusalem and the programme of missionary outreach.

The initial point of continuity and hostility is again the Temple. Stephen, who emerges as a leading Hellenist, provokes a much fiercer reaction over his views on the Temple, which result in his summary execution (chs 6–7). It is the persecution following his death, not any deliberate policy of the Jerusalem church, which results in the first missionary move beyond Jerusalem. Here again, as with the judicial murder of Jesus (a regular motif in chs 1–5), the divine purpose overrules human malice to bring to effect the overarching divine plan (2.23; 4.28; 5.38–39).

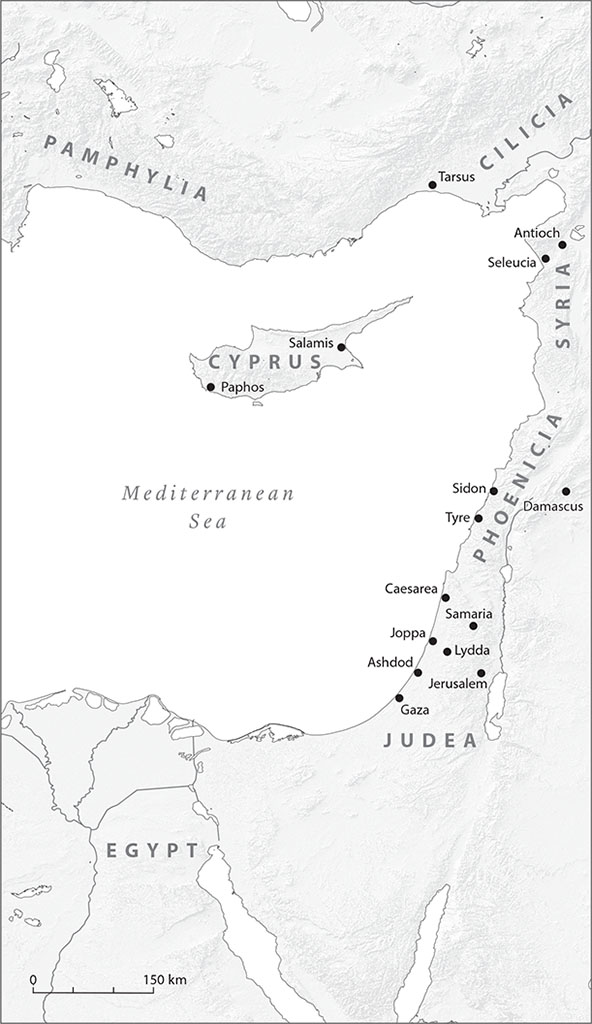

The initial move into Samaria and in the conversion of the eunuch (Ch. 8) continues the Temple theme, since it was dispute over the site of the Temple which was decisive in the schism between Jew and Samaritan, and since the eunuch was typical of those excluded from the Temple because of some defect. The narrow focus on the Temple which characterized chs 1–5 is now radically reversed to open up salvation precisely to those for whom the Temple marked disbarment rather than benefit. It is no coincidence that this double episode of initial expansion also marks a decisive step forward in the programme of 1.8, not only into Samaria, but also already, by implication, to one end of the earth (Ethiopia).

Into the midst of what probably was a continuous Hellenist source (chs 6–8, 11.19–30) Luke has inserted two episodes — Paul’s conversion (9.1–31) and the conversion of Cornelius (10.1–11.18). The space he devotes to both (with two further accounts of Paul’s conversion in chs 22 and 26, and the Cornelius episode not only narrated twice but also cited in 15.7–9) shows just how important they were for Luke and how pivotal is their function in Luke’s portrayal of earliest Christian expansion.

Paul’s conversion is given primacy — not only because it followed directly from the persecution which arose out of the Stephen affair, but also because it prepares for the dominant role which Luke will give to Paul in the second half of Acts. The conversion of the great missionary to the Gentiles is recounted before any real breakthrough to the Gentiles is described. The conversion of Paul, in other words, is the headline under which the subsequent expansion into Gentile territory takes place. For all that Peter supervised the first Gentile conversion, it is Paul who is the dominant factor in what follows.

It was equally important for Luke, however, that the conversion of Cornelius (10.1–11.18) should be recounted before the breakthrough at Antioch (11.19–26). It is this which enables him to attribute not only the evangelism of Judaea to Peter (9.32–43) but also the crucial first acceptance of a Gentile without requiring circumcision. In this way Luke is able to maintain the strongest link between the beginnings in Jerusalem and the critical step which validated the subsequent massive expansion of the Jesus movement beyond the land of Israel. It is Peter’s precedent which validates Paul’s subsequent revolutionary ministry.

The second phase (chs 6–12) is rounded off by an astonishingly brief account of the breakthrough at Antioch (11.19–21) — astonishing in comparison with the space given to the Cornelius episode — in which the stronger concern seems to be to ensure that the Antioch church cannot be seen as independent of the Jerusalem church (11.22–30). It is presumably this concern to maintain Jerusalem as the vital symbol and medium of continuity which also motivated Luke to return his narrative to Jerusalem (Ch. 12) before devoting more or less exclusive attention to Paul (chs 13–28). That the episode ends with Peter himself departing from Jerusalem (12.17) is a signal that the centre of gravity in the Christian mission was beginning to shift from Jerusalem. What began in Jerusalem can now no longer be contained within the terms which Jerusalem historically represented.

Within these episodes the other key identifying marks maintain their prominence. Jesus remains the focus of the preaching: his rejection as the climax of Stephen’s speech (7.52), his place at the right hand of God in Stephen’s vision (7.56), his name proclaimed (8.5, 12; 9.15–16, 27–28; 10.43). And the reception of the Spirit as the crucial mark of divine acceptance is given particular prominence in the two decisive breakthroughs, to the Samaritans and to the Gentile Cornelius (8.14–17; 10.44–48; 11.15–18). Perhaps most striking of all, however, is the way in which the issues which help define identity broaden out from from the intra-Jewish one of the Temple (chs 6–8) to issues of Jewish and Gentile relationship (chs 10–11) and the encounter between the Jewish-Christian understanding of God and that of the non-Jewish world (8.4–24; 10.25–26), with the importance of the latter reinforced by the final episode of the section (12.20–23).