CHAPTER

4

Freddy had a pet ant named Jerry Peters, who lived in the pig pen with him. Jerry had been born and brought up in an ant hill near the henhouse. Young ants are taught just one thing: to be industrious. Even sleep, ants think, is a waste of time; and as for conversation—well, just try to get an ant to stop work long enough to tell you even what time it is.

But Jerry thought there were other things in life besides work. He felt that he had earned his keep if he worked a ten-hour week; and that’s all he did work. The rest of the time he took naps, or went on exploring trips around the farm, followed by Fido, a small brown beetle which he kept as a pet. Fido was about as large as the head of a pin, but he was very faithful, and a good watch-beetle; if Jerry was asleep and a spider or grasshopper came nosing around, Fido would bark to wake him up. Of course it was a pretty small bark, and sometimes Jerry didn’t hear it. Then Fido would bite his leg. The beetle’s teeth were even smaller than his bark, and occasionally even they didn’t wake Jerry. Then Fido would rush at the intruder, snarling viciously. This never failed. Even a caterpillar would flinch when Fido came at him.

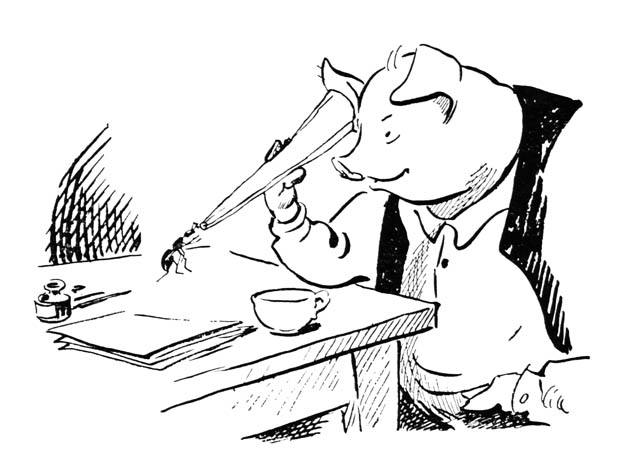

Jerry was quite accomplished for so small an insect. Freddy had taught him to read; he would walk along the lines until he reached the end of the page, where he would wait for the page to be turned for him. He could sing, too, and knew most of Freddy’s cowboy songs. Freddy would have liked to accompany him on the guitar, but of course the lightest touch on the strings completely drowned out the ant’s voice. Indeed, even to hear him, unaccompanied—even for that matter to hear him talk at all—Freddy had to make a megaphone out of a cone of paper and have Jerry shout through the small end.

The other ants jeered at Jerry’s accomplishments. Reading, writing, even talking—all these were classed as “the useless arts.” Even jeering took time from work, and they didn’t do much of it. Mostly they just pushed him aside and went on working.

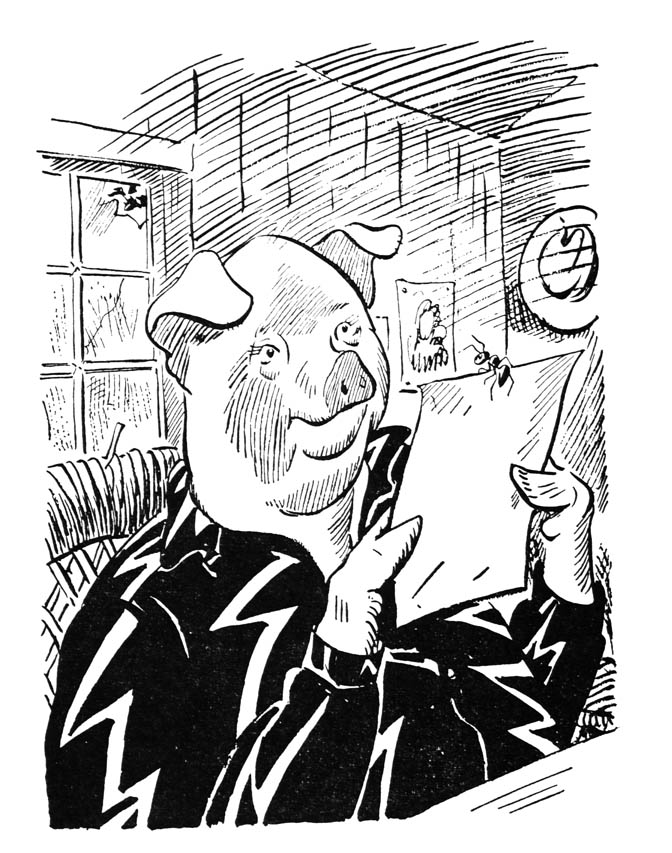

So finally he left the ant hill and moved in with Freddy, who at first, of course, didn’t know he was there. The atmosphere of the pig pen was much more peaceful, and at the same time more stimulating, than that of the ant hill. Everything in the ant hill was rush and hurry, with meals taken on the run and no time for, or interest in, anything but work. Whereas in the pig pen there was a pleasant air of leisure, there were pictures and books, things to look at and speculate about—as well as enough cake and cookie crumbs in the crevices of Freddy’s chair to feed a dozen ants for a year.

I suppose it was Jerry’s curiosity that brought him to the pig pen in the first place. Most ants have no curiosity; that is why they have never got any further up in the scale of civilization. Ants would never speculate about a pig. They would never notice him. If he stepped on their hill and kicked it to pieces, they would never waste time storming at him and calling him names; they would simply go to work and rebuild. But Jerry wondered about things. And from wondering he took to exploring. One day he explored the pig pen. He dined off a small piece of angel cake he found in a crack in the floor. He spent several days poking around in Freddy’s study, and then he and Fido moved in. They took up residence in a dark corner under the bed. He knew that the only thing an ant has to fear in a house is a broom, and from the amount of dust on the floor he felt sure that Freddy didn’t even have a broom.

At first Freddy didn’t know they were there, but then one day when the pig was reading one of his own poems out loud to see how it sounded (he thought it sounded swell), Jerry climbed up on the edge of the paper and waved his feelers at him. Freddy saw that the ant was trying to say something, so he twisted a sheet of paper into a cone, and holding the small end down to his visitor, and putting his ear at the large end, he heard Jerry ask if he would teach him to read.

Jerry climbed up on the edge of the paper and waved his feelers at him.

I suppose Freddy was flattered at Jerry’s interest in his poems. Anyway, he fitted up a matchbox in a drawer of his desk for the ant to live in. Jerry was worried about Fido; he thought perhaps he wouldn’t be allowed to keep pets. But Freddy said he didn’t think the beetle would be much trouble. “As long as you assure me that he isn’t ferocious,” he said. And he typed a sign: BEWARE THE BEETLE, and pasted it on the matchbox.

From the barnyard Freddy rode up to the pig pen. On his desk Jerry, who had been reading page 23 of an account of Freddy’s career as a detective, by Brooks, was asleep at the end of the last line where he had been waiting for Freddy to turn the page for him. Fido, a little dark speck, was asleep beside him. Freddy put the small end of the megaphone down by him and woke him up.

“I’ve got a job for you, Jerry,” he said. “How many ant hills are there in and around Mr. Bean’s front lawn?”

“Ant hills?” Jerry said. “What you going to do—take a census? Oh, I’d guess twenty, twenty-five.”

“I suppose these ants pretty well cover every square inch of that lawn, don’t they, when they’re looking for food?”

“Oh, sure. They send out exploring parties all the time. Mostly soldiers. Because the different hills are always at war with one another. They’re kind of like the different tribes of Indians I was reading about in that book of yours. Boy, there have been some terrible battles on that lawn. Except—well, they don’t seem to have any fun fighting. They don’t put on war paint or have any war cries or anything; it’s just another kind of work to them. Just a job.”

“You mean they don’t cheer when they win? Or sing songs or anything?” Freddy asked.

“There’s one lot that have a sort of song,” said Jerry. “Those big black cannibal ants that live over near the barn. They sing it when they march out on an expedition. They march in a line, all keeping step, and they sing all on one note. It goes like this:

“Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp.

Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp.

Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp.

Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp.”

“H’m,” said the pig. “Melodious, isn’t it? Are there many verses?”

“Dozens. But it isn’t as silly as it sounds, Freddy. They use it to scare us smaller ants. And I tell you, when you hear that song coming nearer, you’re just paralyzed with fright. I suppose it keeps us from putting up a fight. Then the cannibals carry us off and either make slaves of us, or eat us.”

“Well, let’s forget the cannibals,” said Freddy. “They kind of make my flesh creep. Now, these other ants—would they listen to you if you made ’em a proposition?”

“I guess so. If I grabbed one by the leg and held him down. But even then, only if I told him where there was more work.”

“Well, look, Jerry. This mole, today—” And he told the ant about Samuel, and how he had mislaid his valuables under the front lawn. “I said I’d help him find them, and I thought these ants—some of ’em must have run on the stuff. Of course it’s in a mole hole, and—golly, I didn’t think of that!—maybe moles eat ants.”

“Nobody would eat an ant but another ant,” said Jerry. “We’re too sour.”

“Sour? You mean like pickles?” The pig looked at Jerry thoughtfully. “I’m very fond of pickles myself. Oh, don’t look so alarmed; you could be as sour as all get-out but there isn’t enough of one ant even to register on my tongue.”

“Oh, yeah?” said Jerry. “Much you know about it! Why if you were just to bite off one of my legs—” He broke off. “Hey, hey, what am I saying!” he exclaimed. “This is a pretty grisly conversation, pig. What say we change the subject?”

“O.K., but look—would you call in at these ant hills, see if any of ’em have noticed an emerald ring and a gold pencil. And some money. Some of ’em must have seen the stuff.”

Jerry shook his head. “You don’t know much about ants, Freddy. Suppose they have seen it. Telling me about it will be just a waste of good time to them; they’ll just say ‘No’ and go on. Chances are they won’t even listen to my question.”

“Well, offer them something then. How about honey? Ants like honey.”

“Sure. That might work. A jar of honey to the ant hill that finds that mole’s stuff.”

So Jerry went out. But in a couple of hours he was back. “Doesn’t work,” he said. “You know what those guys said? I stopped about six places, and they all said they hadn’t run across the stuff, and then they all said the same thing: that they weren’t going to send out an expedition to find the stuff if other ant hills did. They said they wouldn’t enter into any competition for a prize; that was just gambling, and they didn’t believe in gambling.

“Well, I argued myself blue in the face, but they wouldn’t give in. They just said that all the ant hills sending out expeditions to be the first to find the stuff was a race, and a race with prizes was gambling, and ants never gamble.”

“Phooey!” said Freddy. “They’re awful noble.”

“No,” Jerry said, “they just won’t take a chance on doing work that they maybe won’t get paid for.”

“O.K.,” said the pig, “then we’ll pay each ant hill that sends out an expedition, whether it finds the stuff or not. Let’s say half a cup of honey per hill. That ought to keep ’em happy for a month.”

So Freddy rode over to Mr. Schemerhorn’s and bought a five-pound pail of honey, and then he and Jerry went around and distributed half a cup at each ant hill that agreed to send out an expedition. They didn’t visit the cannibal ants. Everything went well. As they left the front yard Freddy looked back and saw long lines of ants streaming out of their holes.

“You don’t suppose they’ll get to fighting, do you?” he said.

Jerry was riding just inside Freddy’s ear. “I doubt it,” he said. “It would interfere with work. Of course one hill might raid another hill to steal the honey. Or two gangs might meet down in a mole tunnel, and if neither was willing to give way, or if one of ’em took a nip at another when they were passing each other … Ants have pretty short tempers, Freddy. If you interfere with them, they’ll go for you. But there isn’t anything personal about it; it’s just because you’re interrupting their work.”

“But what’s all the work for?” Freddy asked. “They don’t have to work like that just to keep their ant hills in repair and get enough to eat, certainly. Don’t they ever give parties, or sit around and tell stories and sing, or just wander around and look at the scenery? You do those things. But you’re an ant too. You don’t work all day and all night.”

Jerry said: “I don’t know, Freddy. I guess I just don’t care enough about belonging to the biggest ant hill, or having the most food stored away, or having the record for the largest number of ant-hours put in at work per week. But the ants aren’t so much different from the folks in Centerboro that you’ve told me about. Lots of them work harder than they have to, just so they can have as shiny a car or as nice clothes as the people next door. Keeping up with the Joneses—isn’t that what you call it?”

“That’s right,” said Freddy. “It’s just showing off. Well, me, I’d rather have more fun than the people next door, and let them have their shiny car. I don’t want to keep up with anybody; I’d rather take more naps than the Joneses. Speaking of which,” he added, “let’s go back home and take one right now.”