CHAPTER

5

Uncle Ben drove on through Syracuse westward. He saw the planes circling overhead and knew they had spotted him, but he didn’t care. He had made his plan. He didn’t want to hide from them yet. He drove just fast enough to keep well ahead of the cavalcade of cars full of spies that was pursuing him. When, looking in the rearview mirror, he saw the leaders coming into view behind, he touched the accelerator and the station wagon leaped forward, thirty yards at a bound, until they were again out of sight.

He went on through Rochester, then Buffalo, letting his followers keep him in sight. Now it began to grow dark. The planes had gone. Fifty miles west of Buffalo the cars began to put their lights on, and then he stepped on the accelerator and quickly took a lead of three or four miles. With nothing in sight behind him, he slowed down, turned around, and headed back the way he had come.

His pursuers came in sight—a long string of glittering lights; car after car swished by without paying him the slightest attention; for of course they couldn’t see the station wagon or its driver—only its bright headlights. As soon as they had all passed he speeded up; by midnight he was back in Centerboro. He went to the hotel and got a room and went straight to bed.

Uncle Ben had the best sleep that night that he had had in months. There were no stealthy footsteps in the hall, no rustlings in the clothes closet or whisperings outside the window. But he knew it was only a breathing space—it wouldn’t last. Having lost him, in a day or two the spies would come pouring back into Centerboro, trying to pick up the trail again.

And of course he wanted them to. He didn’t want to lose them entirely, because he had to manage it so that one of them would steal the false plans. He wanted to lose them just long enough to give him time to figure out what to do. Freddy was good at figuring such things out. The first thing in the morning he called up the Bean farm and asked Mrs. Bean to send Freddy down to the hotel.

It wasn’t easy to talk things over with Uncle Ben, because Uncle Ben wasn’t much of a talker. He hardly ever said more than three words at one time. When Freddy met him at the Centerboro Hotel he only said two: “Need help.”

“Sure,” said Freddy. “I read your letter. Where are all the spies?”

“Buffalo,” Uncle Ben said.

“I see. You led ’em out there and then doubled back.”

“Back tomorrow,” Uncle Ben said.

“You mean you—Oh, they’ll be back tomorrow,” said Freddy. “I see. And then you’ll be in the middle of a howling mob again. You won’t be able to go to work on the saucer until someone has stolen this”—he pointed to the metal cylinder on the dresser—“and yet the gangs all watch one another so closely that no one gang can steal it. My goodness, this kind of thing can go on for years.” He scratched his head perplexedly. “Look here,” he said suddenly, “the important thing is for you to get your plans—the real plans—out of our vaults, and go to work building your engine, isn’t it? Well, suppose I steal this—suppose I steal it right now. As soon as I’m gone you holler for the police. When the spies get here, they’ll hear all about it and they’ll chase me. They won’t bother with you any more. And you can go up into your workshop and get on with the job.”

Uncle Ben frowned doubtfully. “Danger,” he said. “Disgrace.”

“For me?” Freddy said. “You mean they’ll kidnap me and try to make me tell where I’ve hidden the plans? When they’re all watching one another, I don’t see how they can kidnap me any better than they can kidnap you. And if they do, I’ll tell ’em. That’s what we want anyway—to let ’em steal this thing. As for the disgrace—well, people will call me a thief, and maybe I’ll be arrested and sent to prison. I won’t be able to tell why I stole it and everybody will say I’m a traitor. But how else are you going to be let alone long enough to build your engine? My goodness, Uncle Ben, I don’t want to sound noble, but any good American would sacrifice his reputation to get flying saucers for his country. And I’ll get my reputation back, anyway, once the saucer is built and we can tell our story.”

Uncle Ben argued for a while, but he had no chance arguing against Freddy, who could use fifty words to his one. Anyway, he couldn’t think up any other plan. He gave in at last, and Freddy tore up one of the bed sheets and with the strips tied him into his chair, and tied a strip across his mouth. Then the pig picked up the cylinder containing the false plans. He looked critically at Uncle Ben.

“You’ll do, I guess,” he said. “The chambermaid will release you when she comes in to make the bed. Hold on, though. You get the state troopers in here, and they’re going to wonder what you were doing all the time I was tearing up that sheet. You ought to have been yelling for help.”

Uncle Ben directed his eyes down to the holstered pistols at Freddy’s hips. But the pig shook his head. “Everyone around here knows one of these is a cap pistol and the other one’s for water. I couldn’t have threatened you with them. I ought to have knocked you out. Suppose I bang you with this thing—you’ve got to have a bruise to show.”

But Uncle Ben didn’t care for that idea, so Freddy gave it up. He thought for a minute, and then he said: “Well, then tell ’em that you were asleep and I came in and held a pillow over your face until you were unconscious.” Then he picked up the cylinder and left the room.

Before he left for Centerboro that morning, Freddy had asked Jinx to stick around the pig pen, in case Jerry came back with any news from the ant hills. The cat was disappointed that they had had to postpone their riding trip, but he fully agreed with Freddy that this was no time to leave the farm. Still, he thought he could get in a little riding; he could at least pretend that they had started on their trip. So he put on his riding togs and saddled Bill and rode around the farm for a couple of hours.

It was on his fourth trip past the pig pen that he noticed an ant climbing up the door toward the keyhole. When the insect disappeared into the keyhole, Jinx dismounted, opened the door and went in. He picked up the megaphone and holding the little end down toward the ant, who was crossing the floor toward him, said: “You got a message for me, ant?”

“Are you Freddy?” the ant asked.

Jinx frowned. He was a little irritated that even an ant could mistake his slender graceful figure for the stout form of the pig.

“Freddy asked me to wait here in case there was news from Jerry,” he said. “Are you Jerry?”

“Indeed I am not!” said the ant indignantly. “Even if I am his cousin, I hope I haven’t anything in common with that lazy good-for-nothing! Lolling around under a plantain leaf all day and gossiping with ladybugs and caterpillars! Pah! I’ve no use for the fellow.”

“Well, pah! I guess he hasn’t much use for you, so that makes it even. And now what about him?”

“The cannibals have got him—that’s what. He went with us when our hill started out to hunt for that Mole Treasure, as we call it. We had just gone a few yards down one of the mole tunnels when we heard very faintly behind us the cannibal marching song.

“Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp.

Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp.

“But it got louder and louder, and we knew they were coming down the tunnel after us. You don’t know how terrifying that song is to an ant. There were forty of us, and probably not more than half as many cannibals. But if we had been at our full mustered fighting strength, five regiments, we probably couldn’t have beaten them off, in that narrow space. Cannibals are five times as big as we are, and in any fight we have to win by greater numbers; it takes six or seven of us to pull down a cannibal. And there wasn’t room enough for us to get at them. So we ran.

“Those tunnels branch off in all directions, and run into one another, and some of us went one way and some another; and Jerry and I and two others had bad luck: we ran down and into a dead end. There was no escape. They came after us, picked up Jerry and the two others, and carried ’em off. They missed me somehow; I was all squinched down behind a little pebble, and they didn’t smell me out.

“But just as they tramped off up the tunnel, I heard Jerry yell: ‘Go tell Freddy.’ So—well, here I am.”

Jinx knew something about the ways of ants. “Well,” he said, “Jerry’s gone. Why take time from your work to come tell Freddy about it?”

“We think it’s part of our work. He’s hired us, hasn’t he?”

“I see,” said the cat. “It’s your duty, eh? Very commendable. H’m. I thought maybe Jerry being a relative, sort of a thirtieth cousin or something—maybe you wanted to have us try to rescue him.”

The ant shrugged two pairs of shoulders. “What for? Even if we could, he isn’t any good to the hill—lazy loafer!”

Jinx shook his head. “Boy, oh, boy, what an affectionate lot you ants are! Well, come on, you’re still working for Freddy. Get up on Bill’s neck—you’ll be safer there.” He went out and got into the saddle, taking the megaphone with him. “Over to that ant hill by the barn, Bill,” he said.

The hill of the cannibal ants looked like a small heap of sand by the corner of the barn. The doorway was a hole beside which lounged several big ants with oversized heads and cruel-looking pincer jaws. Jinx knew that they were soldiers, guarding the gate. He dismounted and approached them. “I want to talk to your president or your king or your captain or whoever is in charge here,” he said. Then he put the small end of the megaphone down toward them. “If you speak in this, I can hear you,” he said.

“I’m the captain,” said the biggest ant in a thin rasping voice. “On your way, cat. We have nothing to say to you.”

“But I’ve got something to say,” the cat replied sharply. “You took three prisoners yesterday. I want them turned loose, unharmed. No missing legs and feelers.”

“Mister,” said the captain, “we take dozens of prisoners every day. We’ve got ’em in the dungeons on the fifth level. You want to go down and pick out your three? Step right in.” He laughed nastily, and the other soldiers cackled with him.

“H’m,” said Jinx thoughtfully. “Smart guy, eh? Well, O.K., I accept your invitation. I’ll come in. I’ll dig ’em out.” And with a sudden spring he landed on top of the ant hill and began digging frantically with his sharp claws, sending the dirt flying in all directions.

He hadn’t dug very far however before the soldiers in the underground barracks rushed to the defense. They seemed to come boiling up out of the ground, big black ferocious insects, and although Jinx jumped and whirled as he dug, sending ants and dirt flying in a cloud about him, some of them managed to grab his fur, and they swarmed over him, biting until he yowled in pain, and jumping off the nest, rolled on the ground.

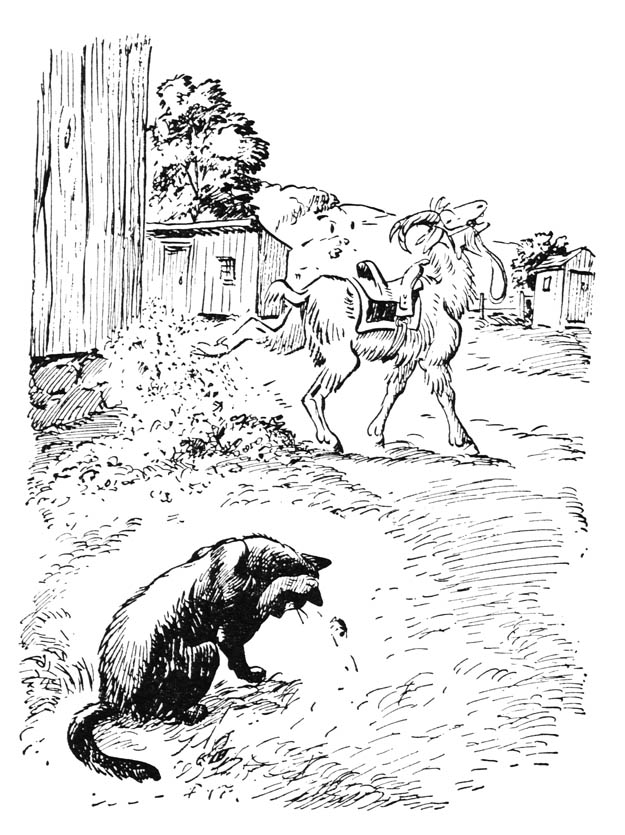

While Jinx was trying to get the ants off him, Bill took a hand—or rather a hoof. He plowed into the hill with all four feet, pawing and stamping and doing a lot more damage than Jinx had, and because his legs were longer and there was no fur to cling to, very few ants got on to him, and those that did, didn’t bother much, because a goat’s hide is thicker than a cat’s.

Bill was having a good time, and the cannibal city would have been ruined for good, if Jinx, having finally got rid of his attackers, hadn’t yelled suddenly: “Hey, Bill, remember Jerry is in there somewhere.”

Bill was having a good time.

So then Bill jumped off. Jinx picked up the megaphone and went slowly closer to the hill, which was now a scene of wild turmoil. It was scooped and clawed out to a depth of nearly a foot, and soldiers and worker ants were dashing about in all directions. “Where’s your captain?” he called; and when the captain came forward, he said: “We mean what we say, ant. Now where are those three prisoners?”

“If it was up to me,” said the captain angrily, “I’d say: go right ahead, destroy our city if you want to. We can rebuild. And then we can take our revenge. We know where you live, cat, and we can visit you there. You can watch and listen, but you have to sleep some time. That’s when we’ll come.”

“Oh, stop talking big,” said the cat. “It’s not up to you anyway, you say. Well, who is it up to, then?”

“It’s up to the queen. She has sent up word that if these prisoners haven’t been eaten, we are to let you have them.”

“Eaten!” Jinx exclaimed.

“Sure,” said the captain. “When the boys get home from a raid they’re hungry. They want a little snack, and they’ll divide up one or two of the weakest prisoners. Good husky prisoners we keep as slaves, to work for us. But those three: I remember, weak little critters, I don’t believe they’ve done a good day’s work in their lives.”

“It’s just too bad for you if you’ve eaten Jerry,” said Jinx. “You’ll have Freddy on your neck, and you won’t—” He broke off. “Ah, here they come,” he said, as three smaller ants, guarded by two huge soldiers, appeared from one of the broken galleries of the hill. “Jerry, is that you?” And when one of the ants, coming forward through the ranks of the cannibals, who drew aside to let them pass, waved his feelers: “Climb up Bill’s leg. Get on his neck and I’ll take you home.”

He was about to jump into the saddle when he noticed that the cannibal captain had come forward and was waving his feelers to attract attention. He pointed the small end of the megaphone down at him. “Yeah?” he said. “What is it now?”

The ant’s voice came up harsh and grating, and vaguely menacing. “Just to warn you. Remember, we’ll be coming up to the house to see you some dark night.”

Jinx cocked his hat over his ear and waved a negligent paw. “Any time, brother—any time.” And they cantered away.