CHAPTER

9

Nothing much happened for a few days. The spies had learned through the radio that Freddy had been arrested and was in jail, and the Centerboro hotel and boarding houses were again full, and a dozen or more tents were up on the fairgrounds. Freddy spent most of his time in his room, watching the spies peering through the fence or peeping out from behind trees at the jail. He kept back from the window, as there was no use letting them know which room he had. He didn’t go out into the grounds much either, because he hadn’t yet decided which of several plans he was going to use to get the cylinder into the hands of one of the spies.

After the first day he did go down to the dining room for his meals, and though at first the other prisoners kept up the pretense of wanting to lynch him, most of them, even the newcomers who didn’t know him, didn’t believe that he intended to sell the plans to foreign agents. Probably because none of them would have so contemptibly betrayed their country, they could not imagine that anyone else would. Only the Yegletts, the four racketeers from the city, still scowled and sneered at him.

On the third day he was taken down to the courthouse to appear before Judge Willey. Every spy in the neighborhood attended the trial; the courtroom was jammed to the doors and many prominent local residents and friends of the accused were unable even to get inside. The Bean animals, however, were provided with seats, since they were admitted as character witnesses.

But the trial was a short one, as Freddy at once pleaded guilty to the smothering and theft charges. Since there was no proof that he had sold or even attempted to sell the plans to the representatives of any other nation, he was not even accused of treason, although there was a good deal of scowling and muttering when he was brought in, and when he stood up to be sentenced the room resounded with angry boos. Judge Willey sentenced him to five years at hard labor, but in consideration of his hitherto blameless reputation, the hard labor part was remitted. He was then returned to his cell at the jail.

Through Horace and other operatives of the A.B.I., Freddy was in constant touch with Uncle Ben and his friends at the farm. Uncle Ben had got the real plans from the First Animal Bank and was working hard at the saucer engine. The spies hadn’t bothered him. One or two had been sneaking around, but as Uncle Ben had given out that the plans Freddy had stolen were the only ones in existence, and that he was now working on a new type of phonograph that would play both sides of the record at the same time, they were all now concentrating on Freddy.

This of course was what Freddy had wanted, since Uncle Ben was free to work on his engine. Life in the jail was pleasant enough; there were games to play and TV to watch and lots of good things to eat. But he couldn’t go outdoors, or out for the evening with the other prisoners, and when they went to the movies he had to be content with being told about it afterwards. And as everybody knows, there’s nothing duller than listening to old movie plots.

There was, too, the disgrace of being a convicted criminal, and the danger of being kidnapped and tortured to make him tell where the plans were. Naturally he would tell, but he would have to undergo a little torture to make it look good. The idea was not specially appealing. Indeed he could feel the curl coming out of his tail at the mere thought.

What he was really tempted to do was run away, and thus avoid the hatred and contempt of the townspeople and of many of his old friends. It was easy enough to do. As the sheriff said, the jail was easier to get out of than to get into. To get in you had to commit some kind of a crime but to get out, you merely told the sheriff that you were going downtown to buy a bag of peanuts, or that you were invited to dinner at Mrs. Winfield Church’s. Of course he would need a disguise to avoid the spies. But Freddy was a past master at disguise. He had dozens of costumes and wigs at home; all he’d have to do was get somebody to bring him down one. Then, when the engine was finished and the Air Force had taken over, he could come back and tell the true story. He liked to think about that. There’d be banquets (for Freddy) and speeches (in praise of Freddy) and generals presenting medals (to Freddy).

But he couldn’t do it. He had to get the plans into the hands of one gang of spies. Until he did, there was danger, both for Uncle Ben and himself. So he thought hard.

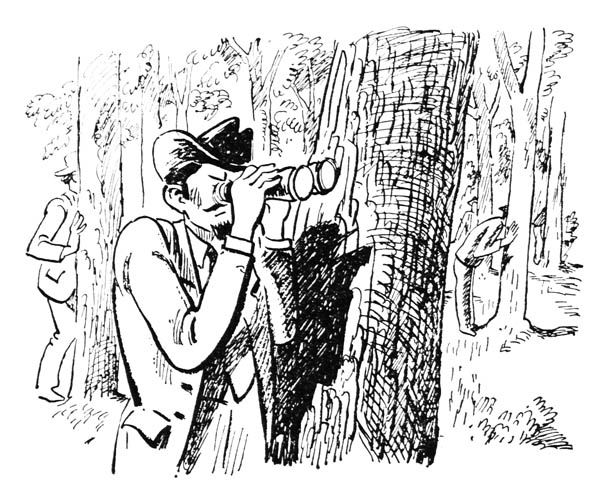

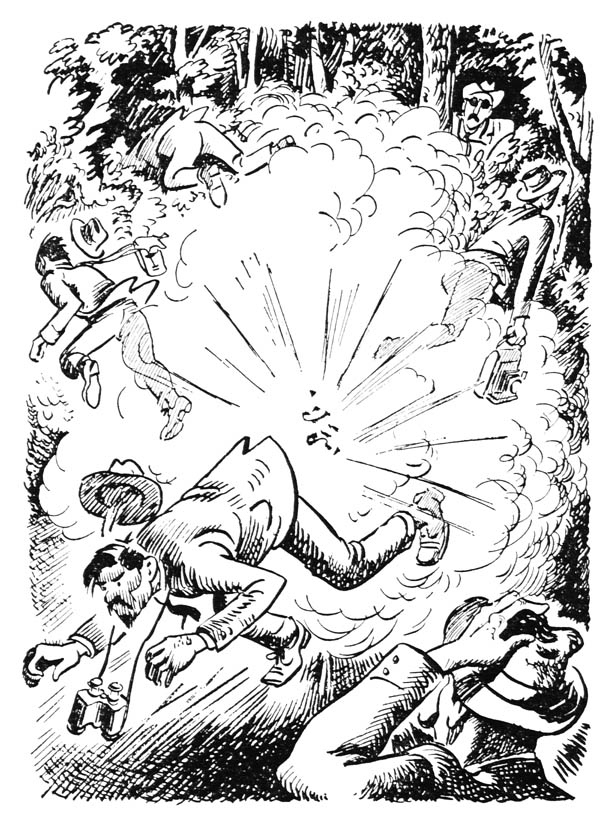

The spies were thinking hard too. Thinking and lurking. They had become very good at lurking; after the first day or two, from the jail one could hardly ever see the lurkers, hiding behind walls and trees and bushes, watching in the hope of locating Freddy’s room by catching a glimpse of him at a window. The only way anyone knew they were there was when one of the prisoners would light a giant firecracker and toss it over the fence. Then half a dozen spies would suddenly dash from their hiding places to find cover at a distance from the explosion.

Then half a dozen spies would suddenly dash from their hiding places to find cover.

These firecrackers had been made one summer by Uncle Ben, when he was working on the exploding alarm clock which had been such a success commercially. Several of the prisoners had bought some of the crackers from him. It was of course against the law to shoot off any kind of fireworks within the city limits; there was a penalty for it of ten dollars or ten days in jail. This was just made to order for prisoners whose sentences were about to expire. They could get an extra ten days added by shooting off something. Otherwise, in order to stay in jail, they would have to go to the trouble of passing a bad check or burglarizing someone’s house. In order to make it easier for them, the sheriff kept a supply of firecrackers always on hand, which he sold to them for a nominal sum.

But though the spies lurked and thought, neither activity brought results. Not until the slender man with the small neat beard had an idea. It was probably the first idea that any of the spies had had. Mostly they just hung around and watched for Freddy and hoped they could get him alone in a dark cellar where they could bang him on the head until he told them where he’d hidden the plans. This gave them lots of time to think, but their thinking was a pretty poor grade of thinking and until this man—Penobsky was his name—had his idea, nothing that was worth trying had come to the surface.

Penobsky realized that his idea wasn’t a very good one, but it was all he had, and so he acted on it. He had lived in America a good many years. When he was twenty he had joined the Communist party, more because red was his favorite color than for any other reason. Also he liked to go to meetings and applaud. It made him feel that he belonged to something.

This is a very important feeling to have, but it would have been better for him if he had joined something whose purposes he understood, like Rotary or the Salvation Army. After a while he began to feel this dimly himself. So having saved a bit of money—he was a plumber, which is a well-paid profession—he went abroad to find out.

When he came back a few years later he didn’t know any more than he had before. But the Communists had supposed that he knew what they were up to because he was so enthusiastic, and so they didn’t try to explain. It is always a lot of trouble to explain something that you don’t understand yourself. And—because it is always easy to be enthusiastic about something you don’t understand—Penobsky kept right on being a Communist.

Also he had been offered a job as a spy. And as he felt that this was a step upward in the social scale, he put away his plumber’s tools, washed his face and hands, grew a small neat beard, and took it.

Penobsky knew from watching the jail that the sheriff and a good many of the prisoners always went to the local ball games. But he had never seen Freddy leave the jail. On the Saturday after he got his idea, the Tushville team was coming over to play a double-header against Centerboro. He shaved off his beard, bought a secondhand bag of plumber’s tools, put on a pair of dirty overalls, rubbed a lot of black grease into his hair and over his face and hands, and walked boldly up to the jail and rang the bell. None of the other lurking spies recognized him, so they didn’t interfere.

“Sheriff asked me to stop by,” said Penobsky to Louie the Lug, who opened the door. “Leak in the hot-water line.”

“I don’t know nuttin’ about it,” said Louie.

“It’s in the bathroom,” said Penobsky.

“There’s twenty bat’rooms in dis jail, chum,” Louie said. “Dis ain’t no cheap flea bag. Every guy’s got his own private bat’room, even sheriff’s got one.”

“O.K., your highness,” said Penobsky, “let’s see ’em all.”

So Louie showed him through the jail. He went into all the bathrooms and turned faucets on and off and whacked pipes with a hammer. Most of the prisoners weren’t home; those that were said they didn’t have any leak. He didn’t stay long in any of the bathrooms; he was looking for Freddy, and at last he found him.

Freddy was lying on his bed, reading. He said he felt it was his duty to read during his spare time, to improve his mind. He was reading a book on the lives of famous bandits. Of course some books improve the mind more than others. There was a tap on the door and he said: “Come in,” and Louie brought in the false plumber. “Dis guy’s lookin’ for a leak in de hot water.”

“Haven’t got any leak,” said Freddy.

Penobsky had recognized Freddy immediately. “Better be sure,” he said, and started for the bathroom.

“But I tell you—” Freddy began. Then he stopped and wrinkled up his nose. “Perfume!” he thought. “That’s the terrible perfume from my water pistol. How could this guy … Golly, if he shaved off his beard and dirtied his face …” Then he said: “Come to think of it, there is a little leak, back of the tub. Better take a look.”

As Penobsky passed the bed to go into the bathroom the smell came stronger. This was certainly the spy he had squirted with perfume in Uncle Ben’s shop. Freddy thought furiously for a minute. “If I was in his place, what would I do? I guess I’d get rid of Louie, and then I’d tie me up and twist my arm until I told him where the plans were. Yeah, only I don’t want my arm twisted. And if I just handed ’em to him, he’d smell a rat.”

His thoughts were interrupted by a call from the plumber. “Boy, I’ll say you’ve got a leak!” And as they looked in the door, sure enough, water was squirting out of the hot-water faucet and hitting the ceiling. “Better go down cellar and shut off the water,” Penobsky said to Louie, “or we’ll flood the jail.”

“Louie, you stay right here,” Freddy said. He had no intention of being left alone with a probably cruel and merciless spy. On the other hand, the spy must somehow be kept from leaving. For an idea had come to Freddy and he thought it might work. He said to Louie: “This guy isn’t a plumber. Not if he doesn’t know enough to shut off the water before he takes a faucet off.”

“If dere ain’t any leak, he makes one,” Louie said. “Maybe he is a plumber at dat—wants to make a job for himself.” Louie was smarter than he looked.

“I think he does, and he wants to make it in my bathroom because he’s after me,” Freddy said. “He’s a spy. So let’s lock him up until the sheriff gets back.”

So they shoved Penobsky into the room named Fagin, and then, having turned off the water, went up and put Freddy’s faucet on.

In the cellar, while turning on the water again, Louie said: “Hey, Freddy, you don’t suppose dat plumber guy will escape t’rough de window, do you?”

The sheriff liked to please his prisoners, and so although there were iron bars on all the windows, he had had them fixed so the whole frame, bars and all, swung outward. He did this because the bars made some of the prisoners nervous—they said they made them feel shut in. Of course it looked all right from the outside, but as the sheriff knew, it’s not pleasant to feel that you’re shut in and can’t get out. It was very thoughtful of him.

“He doesn’t know about the windows,” Freddy said. “But anyway he won’t try to escape; if he’d wanted to he’d have pulled that gun on us that was sticking out of his pocket.”

So when the sheriff came home Freddy took him up to see the prisoner.

The sheriff looked at him with distaste. “He’s pretty dirty,” he said. “What charge you expect me to hold him on?”

“Impersonating a plumber,” said Freddy promptly.

“I am a plumber,” Penobsky said and showed them his union card.

“Well, then,” the sheriff began. He obviously didn’t want to have this greasy and grimy creature in his nice clean jail.

“Carrying concealed weapons,” said Freddy. And he slid a fore-trotter into the man’s pocket and pulled out a pistol.

The sheriff said reluctantly: “We-ell, I s’pose if he’ll take a bath. And wash out the tub afterward—”

“I can’t take a bath,” said Penobsky. “Against doctor’s orders.” He was afraid Freddy would recognize him if he washed his face. He didn’t know of course that the pig had spotted him by the perfume.

“Well, you can’t stay in my jail unless you do,” said the sheriff.

“It’s honest dirt,” the man retorted.

“Well, there ain’t any place for honesty in a jail. So we’ll just let it go down the drain. I’ll give you a choice; either you take a bath, or I’ll have the boys give you one. With yellow soap and a scrub brush.”

“There ain’t any bathroom with this room,” said the man sullenly.

Here was the opportunity that Freddy had been watching for. He looked meaningly at the sheriff. “He can use my tub if he’ll scrub it out. And if he’ll mop up the mess he made in there monkeying with the hot-water faucet.”

The sheriff said all right, and when Penobsky had gone into Freddy’s bathroom and shut the door, the pig took the sheriff out into the hall. “Look, sheriff,” he said, “don’t give this guy that single room. Put him in my room, there’s two beds there.”

“Got one of your ideas, hey?” said the sheriff with a grin.

“Yeah,” said Freddy. “If it works I’ll tell you about it in the morning.”