CHAPTER

11

In case he got the plans, Penobsky had made careful arrangements for his getaway some time before. Passing himself off as an artist named Smith, he had rented a house not far from the small farm where Freddy had taken refuge from the state trooper. The huge lawn sloped away gradually on all sides from the house, and there was a clear view for a hundred yards in all directions—not a tree or bush stood anywhere within the high iron fence that surrounded it. There were three other men living there—one of them was the big fierce man with curled-up eyebrows. One always stayed with the house while the others were out spying.

Penobsky knew that even if he got the plans, it was going to be hard to get them out of the country. Not only because the spies of the seventeen other nations who were after them would be on his trail, but because the U. S. Government would be watching all the seaports and airfields as soon as it was known that he had them. But the main thing was to get them, and to keep them afterwards. Then he could wait until a good opportunity came to get away. He had plans for that, too.

The only thing he hadn’t been able to plan for was how to get away from the jail unseen by the other spies. And he didn’t. Cautious and quiet as he was, dozens of eyes, peering from behind trees and peeping through bushes, spotted him at once, and there was a general rush for the gate, which was the only exit from the grounds.

With the plans actually there, there would probably have been a terrible free-for-all fight, in which indeed the plans might have been destroyed. Cy, saddled and bridled, was drowsing under a tree near Freddy’s window, as Freddy had asked him to. Realizing what had probably happened, and fearing that this man might not be able to escape, he trotted out. Penobsky ran to him, jumped into the saddle, and with a rattle of hoofs they were through the gate, scattering the spies like a bunch of chickens and knocking two of them endways. And then they were galloping up the empty steet while the spies ran for their cars.

Once outside the town, Penobsky made crosscountry for his house, and the lights of the cars died away behind them. He kept on steadily for an hour, crossing several roads, even cantering for a mile or so along one stretch, until pursuing car lights made them take to the fields again. When finally they came to the house, Penobsky pulled up in the gateway and gave a peculiar whistle. At once a searchlight on the porch was turned full on him. Cy blinked in the glare. Then the light went off and somebody called out something in a strange language. Penobsky dismounted, gave Cy a whack on the flank and said “Go home,” and started up the drive. So Cy went back to the jail.

In the morning, Freddy told the sheriff the whole story. “I don’t think we ought to say anything about it though,” he said. “If they were the real plans, getting them back would be a cinch, because Cy knows where this spy is, and the state cops could besiege the house, and make him surrender. But we don’t want to get them back. They’d be given to Uncle Ben, and then the whole business would start over again, with the spies and everything.”

“Spies are mostly gone this morning,” said the sheriff. “Mike threw a firecracker over the fence after breakfast and didn’t flush one of them.”

“Sure. They saw the plumber escape. They’re after him now, and that’s fine. But look, sheriff; that mosquito—I’m kind of worried about her. She did a fine patriotic act, and I haven’t heard a peep out of her. Suppose she got hurt when the guy sneezed?”

“She may have been blown into a corner somewhere,” said the sheriff. “Why don’t we get the vacuum cleaner and see if we can pick her up?”

But Freddy thought that might be dangerous. “Suppose she’s injured. I wish you’d help me look for her. She took a big risk—really, you know if you or I had done that, they’d have given us the Congressional medal.”

“Well,” said the sheriff dryly, “I can’t imagine doing it in the first place, and in the second, what would she do with the medal? Hang it round her neck? However, I’ll say this: if we find her she’ll get a free meal in this jail any time she asks for it, and no fly swatters.”

It isn’t easy to find a mosquito in a large room when you want one—not that you usually do. But the strange thing was that they did find Sybil. She had been blown by the sneeze under Penobsky’s pillow, and when they lifted it, there she was, lying on her side and moaning feebly. She had a broken wing.

The sheriff got a match box and put cotton in it, and then they put the injured mosquito in it. They couldn’t of course set the wing, but the sheriff looked at it under a magnifying glass and said he thought it would heal all right. He gave her some breakfast, and then leaving her resting comfortably went down to his office.

“What I’d like to do, sheriff,” said Freddy, “is get away for a while, until Uncle Ben has his engine made and can clear my good name. How’d this be. Jinx and I have been planning a riding trip, and we’ll go. You give out that you’re keeping me, as the perpetrator of a dastardly crime against my country, in solitary confinement in the dungeon under the jail.”

“There isn’t any dungeon, Freddy,” said the sheriff. “Goodness, you ought to know that I wouldn’t have any such horrible place to stick my boys into.”

“Well, and I won’t be in it, either, so that’s all right,” said the pig.

“Eh?” said the sheriff. “Oh, I get you. On bread and water?”

“No,” Freddy said. “People could imagine me in a dungeon, but they couldn’t imagine me living on bread and water. Not with my appetite. No, regular meals; but no light, except what filters through a tiny barred window, high up in the damp and slimy walls.”

The sheriff shivered. “Rats?” he asked.

Freddy thought a minute. “No,” he said, “I think not. Snails.”

The sheriff shivered again. “I feel terrible for you, Freddy,” he said.

“So do I,” replied the pig. “We must both remember that I won’t be there.… Well, I’d better escape tonight, if it’s all right with you.”

“Some of the boys will be going to the movie tonight,” said the sheriff. “Better wait till after midnight. They go early, but some of ’em stay right through the second show, and then they go get a soda afterwards. But they’re usually in by twelve.”

Freddy didn’t say anything about all this to Horace, the bumblebee, or to any of the other operatives of the A.B.I. who came during the day to collect information or take back any messages he might have for his friends. The fewer animals or people that knew that he was no longer in the jail, the less trouble it would be for everybody.

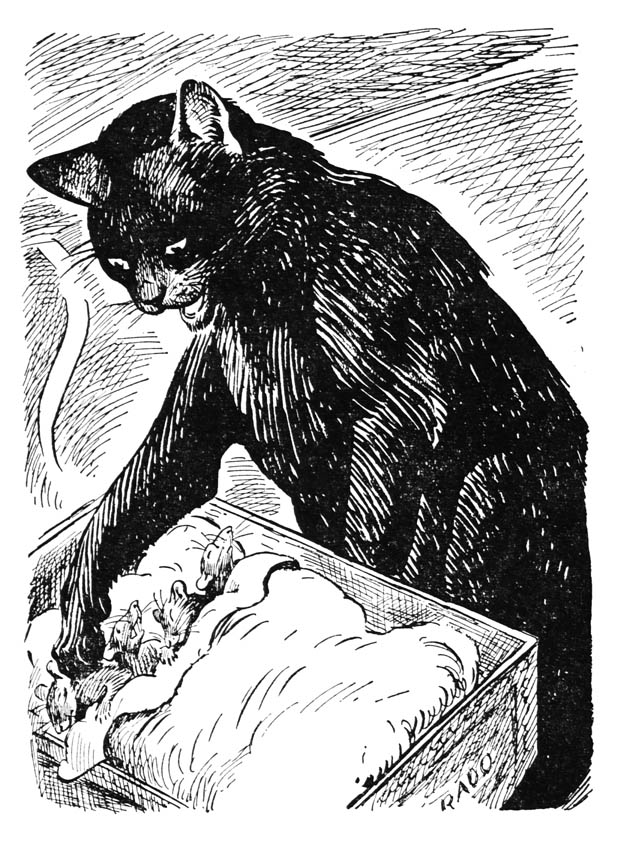

That night, back at the Bean farm, the four mice—Eek and Quik and Eeny and Cousin Augustus—went to bed at nine o’clock in their cigar box under the stove. And behind the stove Jinx curled up on his red cushion. But nobody slept well, for Cousin Augustus tossed and turned and disturbed the other mice, who squeaked their protests; and then from muttering, Cousin Augustus began talking, so that what he said could be understood.

The mouse’s voice wasn’t loud enough to keep Jinx awake, but what annoyed the cat was the things Cousin Augustus said. He was calling some cat all the insulting names he could think of. Jinx knew quite well that the insults weren’t meant for him; he was on the best of terms with all the mice. He just didn’t like to hear any cat—even an imaginary one—called names by a mouse. To sit quietly and listen to it was in his opinion not dignified.

He got up and went over to the cigar box, with the intention of lifting Cousin Augustus out and giving him a good shaking. But in the dim light from the kerosene lamp which Mrs. Bean always left turned down on the kitchen table, the four mice looked so innocent and helpless, all lying spoon fashion in the box with Cousin Augustus in the forward position, eyes tight shut and whiskers twitching as he muttered his insults, that the cat grinned and got over being mad. He just carefully shut the lid of the box and went back to his cushion. The mice would be all right, he knew; the lid had holes in it so that in winter if the kitchen fire went out, it could be closed down and they would be warm and could still breathe.

Now it was lucky for Jinx that he hadn’t gone right to sleep. He wouldn’t have heard something that he did hear. It was very faint—hardly more than a whisper in the still air of the kitchen.

Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp.

Tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp, tramp.

It was the marching song of the cannibal ants.

Jinx was off his pillow in a bound and he threw open the lid of the cigar box and shook the rearmost mouse by the shoulder. This of course shook all the mice and they awoke immediately—all except Cousin Augustus, who snapped his teeth and kicked out with all four legs—imagining, I suppose, that he was being attacked by the dream cat.

“Wake up, boys, and scatter,” said the cat. “Trouble coming. But it’s aimed at me, not you. Better go into the parlor. It’s the cannibal ants. They said they’d get me, and they’re out to do it.” He stopped and pointed to a thick black line that seemed to have been drawn from the keyhole of the back door, up the wall, and halfway across the ceiling toward the stove. Another black line was creeping slowly forward across the floor.

“Wake up, boys, and scatter,” said the cat.

“Golly, Jinx, don’t let those ants get you or they’ll eat you alive,” said Quik; and Eeny said: “They’ve divided. That gang is going to drop on you from above, and the others are going to attack from the floor. Come on, Jinx; let’s get out of here.”

But the cat only grinned. “Stick around, mice,” he said. “I’m going to give these boys a tonic—liven ’em up a little.” His gun belt was beside the cushion—in it were duplicates of the weapons Freddy carried; a cap pistol and a water pistol. He pulled a bottle out from under the cushion and filled the water pistol from it.

A strong and sickly sweet smell of cheap perfume filled the air. The mice began to sneeze. “Get under the table, boys,” Jinx said. “You ain’t smelt anything yet.”

Ants haven’t very good eyes. They learn about the world by smelling of things and touching them with their feelers. So the cannibals, as they massed together on the ceiling above the cushion, preparing to drop on Jinx, didn’t see that he wasn’t there. Nor did the column that was approaching across the floor realize that he was not in his accustomed place. So when he pointed the water pistol at the mob on the ceiling, and squeezed the bulb, they were taken completely by surprise. The thin stream of perfume hit them and then traveled along the line of march, across the ceiling and down the wall to the keyhole. Then he quickly reloaded from the bottle and sprayed the entire length of the column on the floor.

The whole ant army was thrown into complete confusion. Most of the ants on the ceiling dropped to the floor and lay there kicking or trying to wash the terrible perfume off their faces with their forelegs—for if its effect on Penobsky had been so powerful you can imagine what it would be on a creature as tiny as an ant. Jinx reloaded his pistol again, but the army was in no condition to carry on an attack. They spread out over the floor, kicking and sneezing; many of them were scrambling toward the door. The cannibals were in full retreat.

But Jinx knew the grim doggedness of ant nature. They would never give up. They would be back—if not tonight, then some other night. Eek came out from under the table, holding his nose with one paw, and pointed this out. “What are you going to do, Jinx?” he asked. “You can’t squash a whole army.”

“Certainly not,” the cat snapped. “Not when I’ve already licked them. I’ve got an idea. You boys want to come with me—over to the ant hill?”

“What!” Eeny squeaked; and Cousin Augustus said: “What’s the idea? You want us to be eaten alive?”

“Look,” said the cat, “every soldier in that hill came along on this expedition. They’ve never tackled anything as big as a cat before, and they’d be fools if they didn’t bring the full strength of their army. I’ll bet there isn’t more than half a dozen soldiers left at the hill, to guard the gate and look after the queen’s safety. O.K., let’s snatch the queen. What do you say?” He got up on the table where he could reach the door knob, turned it, and opened the back door.

“Yeah!” shouted Quik. “Sure, cat; we’re with you!” Eek and Eeny chimed in. But Cousin Augustus said: “Well, I’m not going. Those cannibals—if one of them bites you and you cut his head off, he goes right on biting. One bit me once—I’ve still got the scar. Look at it, down by the end of my tail.”

“Aw, you’ve shown it to us about a hundred times,” said Eeny, and Quik said: “Couldn’t even see it with a microscope.”

Eek said angrily: “It’s mice like you, Gus, that give the whole mouse nation a reputation for being sissies. This army can’t get back to the hill for at least half an hour, and we can get there in five minutes. Now you come along and no more nonsense, or I’ll put a scar on your tail that’ll really show.”

So Cousin Augustus went along, but he grumbled a good deal.

It was easy enough, as Jinx had thought. A swift attack with the cat’s claws scattered the few guards, and then Jinx dug down to the queen’s apartments, a foot or so down. The moon gave enough light for animals to work by. Here there were only laborers, and nurses for the queen’s children. The queen was big, much bigger than even the largest of her soldiers. Jinx scooped her out with a claw, and then Quik grabbed her, and carried her back to the kitchen. And it was just as they were looking for a safe place to put her that Freddy walked in.