CHAPTER

15

The mice explored the cellar first. They found many interesting and unusual things—one always does in cellars—but nothing that told them anything about the present occupants of the house. At some time the house had been lived in by other humans, and by mice. The two species had evidently been on good terms—as mice and men usually are, until the mice begin to get into the package goods. There were mouse nests and there were runways up through the walls to the upper stories, and as they found later, entrances for mice gnawed in corners of nearly all the rooms. It was an easy house to explore.

On the first floor there was a good kitchen and a well-stocked pantry, but the other rooms were scantily furnished except for two machine guns at the living-room and dining-room windows, and several rifles and shotguns scattered about. There were four bedrooms on the second floor, and on a table in the largest one was the cylinder containing the good plans.

“Has Uncle Ben got the other plans, the no-good ones, with him?” Eeny asked.

“I think so,” said Quik. “I think he’s got two sets of false plans, just in case. They’re in the locker in the caravan.”

“Why couldn’t we go get one of ’em and push the tube up here through the tunnel, and take this one back with us?” said Eeny.

“The tunnel isn’t big enough,” said Cousin Augustus. “And it isn’t entirely straight; if we got stuck halfway we’d be in a nice mess.”

“And how could we get it down to the cellar and out of the door?” said Quik.

“Yeah, I guess you’re right,” Eeny said. “But couldn’t we get the plans out and chew ’em up? Then the spies couldn’t use ’em.”

“Neither could Uncle Ben,” said Eek. “It’s got to be something better than that.”

There were four men in the house: Penobsky, Smirnoff, the big man with the curly eyebrows, and two other short, thickset men, with broad flat faces, whose names seemed to be Franz and Ilya. It was easy for the mice to go on exploring and still keep out of their way. They patrolled the house, but their eyes were on the windows, and if the mice ran across the floor they never noticed them.

At ten, Penobsky went to bed in the big room where the plans were, and Ilya in one of the smaller rooms. Smirnoff and Franz put out the lights inside, and took up places by windows on opposite sides of the house. Evidently they kept a twenty-four-hour watch.

About midnight the telephone rang. Penobsky answered it, but he spoke in a foreign tongue. At the end, however, he lapsed into English. “This is you, Rendell? I do not wish to speak to you. You take your orders from Paul.… Yes, Friday. Or if it storms, the next calm night after that.… Yes, we will put the lights out at ten. Good-bye.”

The mice held a whispered conference under Penobsky’s bed. It was perfectly safe. A mouse’s whisper is much too light to be heard unless you put your ear right down next to him. But they couldn’t figure out what Penobsky had meant, and the names Paul and Rendell were unknown to them. Maybe Freddy could work it out. They decided to keep watch all night and report to him in the morning.

At two, Smirnoff and Franz went to bed and the other two took up the watch. The four mice continued to prowl about. They got into Penobsky’s suitcase and found a number of letters, but they were all written in some foreign language.

“I wish I’d taken up languages,” said Eeny. “Do you suppose there’s anything important in these letters?” Eeny was always asking questions beginning with “Do you suppose,” or “I wonder if.” A lot of people do that. And of course there are never any answers.

Nobody answered this question, so Eeny went right on. “I wonder if the mice in Europe speak foreign languages,” he said. He waited for comment, and when none came: “They say foreign languages are very hard to learn, so probably they don’t,” he said.

“So is English a hard language to learn,” said Cousin Augustus with a sniff. “I wish you’d learn to talk sense in it.”

Eeny got mad and went off into Smirnoff’s room. The big man was sleeping on his back with his mouth open. On the table beside the bed was a glass of water and a pistol and an open box with some pills in it. “Wonder if I can make a basket,” said the mouse to himself, and he giggled and picked up one of the pills in his paws and tossed it neatly into the open mouth.

“Glug!” said Smirnoff, and he sat up suddenly and glared around him, feeling of his throat.

“Score two for our side,” said Eeny to himself. He had jumped down and was under the bed. He had to stay there for about ten minutes, while the big man put on the light and looked around to try to find out what had happened.

When things had quieted down and Smirnoff was asleep again—he was on his side now and his mouth was tightly closed with one hand over it—Eeny got back on the table. He thought it might be fun to shoot off the pistol. But he couldn’t find the safety catch, and that was a good thing for him, because if he had pulled the trigger and the pistol had gone off, the recoil might have knocked him across the room.

He waited a while, thinking that Smirnoff might turn over on his back again and open his mouth, and he could practice shooting some more baskets. Then he thought maybe he hadn’t ought to, maybe if the man swallowed too many of his pills it might make him sick. So he went on exploring the room, taking note of everything for his report to Freddy.

It took several hours for the mice to make their reports in the morning, but when they had finished, Freddy had a pretty clear picture of the inside of the house, and of the way the spies lived.

Occasionally through the day one of the spies who had set up the road block, or who were watching the house from one side or another, would saunter past on the other side of the brook. These men apparently did not look on the gypsies as rivals. It did not occur to them that wandering gypsies, who owe allegiance to no government, would be interested in the saucer plans. But like everybody else, they were curious about gypsies, and in telling fortunes; and seeing what they thought was a swarthy, gaudily dressed gypsy woman, more than half of them crossed the brook on stepping stones at the head of the pool and asked to have their fortunes told.

It always seemed to Freddy’s friends that in even the most elaborate of his disguises, his nose should have given him away. It was not a human nose, it was a pig’s nose. But Freddy in disguise was like those puzzle pictures that are captioned: “What is wrong with this picture?” You have to hunt for the detail that is wrong. And there was no caption under Freddy. You saw a gypsy woman—the swarthy complexion, the black braids, the head tied in a bright scarf, the big earrings, the full, gaudy skirts. People see what they expect to see. You never noticed the pig’s nose.

Freddy took in more than fifteen dollars that day. And I think they got their money’s worth. He sat at a card table and the men laid their hands, palms up, on the table in front of him. He did not touch the hands but kept his sand-filled gloves folded in his lap as he bent over to read the lines. And he told them of success and great obstacles surmounted, of riches, and of hidden talents, revealed by these lines, but unsuspected by their possessors. Every man whose fortune Freddy told was destined to find fame and fortune as a musician, a statesman, an actor, a scientist—always in some profession which the man knew nothing about. For, as Freddy knew, it is easier to believe in a hidden talent if it is in a field of which you know nothing. And each one went away happy in the belief that he had only to give up spying and take up some other profession, to become a tremendous success.

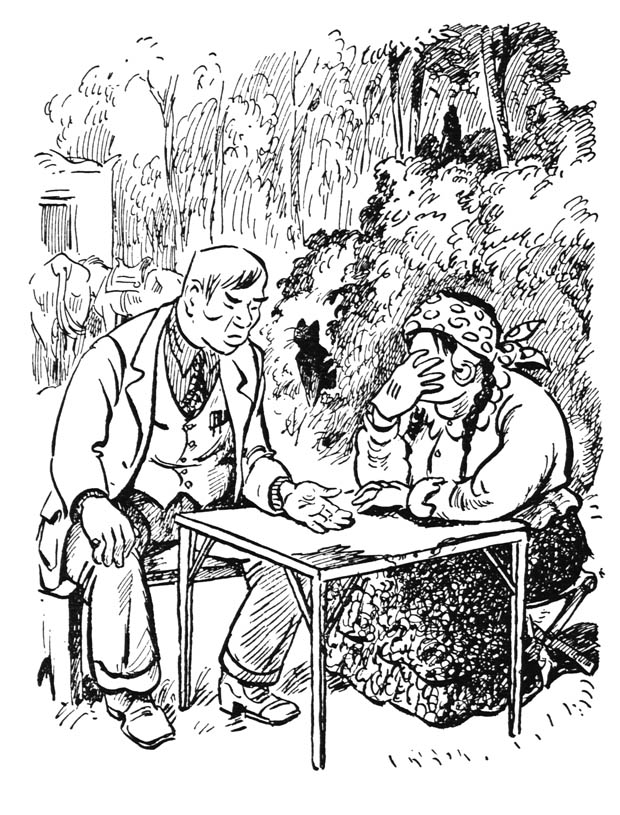

But when Smirnoff came down the path to have his fortune told, Freddy changed his tactics. The big man pretended that the fortune-telling was just a joke, that he had come just for entertainment and to pass the time. “Is mooch money in these hand, no?” he said with a grin. “You see maybe rich wife I shall marry, eh?” But Freddy knew that he was superstitious, and could perhaps be made to believe that the gypsies could help get the plans out of the country.

“There is not much money in this hand, no,” Freddy said. “There is some sickness. Not bad sickness, but you must take medicine, pills.” He shook his head. “But that is not important. There is trouble—an accident. It has not happened yet. It is …” He paused. “Let me see if I can get it this way,” he said, and closed his eyes and covered them with one of the sand-stuffed gloves.

“Let me see if I can get it this way,” and closed his eyes.

For a minute or two he didn’t say anything. Then: “I see a room,” he muttered. “It has two windows to the south and two to the east, one of them cracked. The wallpaper is dark green, and there is a bright-colored calendar between the east windows. It is a picture of a little girl hugging a big dog. There is a big bed of dark wood and there is a small man in it. There is a table in the center of the room and on it is something—a sort of tube. It has something in it—could it be maps?”

At this Smirnoff, who had become more and more agitated as Freddy went on with the description of Penobsky’s room which the mice had given him, drew in his breath sharply. “Stop!” he said. “How are you knowing this? You could not—”

“Quiet,” said Freddy. “I see other things, too. I see a man—someone you are expecting. His name is Cran-Crandall. Wendell. I cannot make out. It is to him the accident happens. He cannot come to you. There are men—they are shooting at him.” Freddy stopped suddenly and uncovered his eyes. “That is all I can tell you, gentleman,” he said.

Smirnoff stared at him. It was plain that he was thinking that there was no way in which this gypsy could have known about Penobsky’s room, about the tube containing plans on the table, or that someone named Rendell was coming. After a moment he said: “This man you call Crandall—you are saying he cannot come here?”

Freddy sat up straight. “That is your fortune, my gentleman. That is all I can tell you.” Then, as the spy merely continued to stare at him, he said: “That is what I have seen with the eyes of the mind. But with these eyes”—he touched them—“I have seen other things. Men behind trees and walls, watching the house. Men down the road and up the road, armed men. What will you give Zelda if she can drive them away? So that the road is open?”

Smirnoff narrowed his eyes and stared at Freddy. After a minute he said: “The road—is not need to be open. But you can do thees—drive these men?”

“For one hundred dollars, yes.”

The spy didn’t haggle. When the road was clear and there were no more men lurking behind trees and walls, he would pay Freddy the hundred dollars.

The next morning Freddy took one of the tubes containing false plans and strapped it to his leg under his skirts. He saddled Cy and rode slowly down to where the spies had their road block. There were a dozen cars parked beside the road, and back among the trees were a number of tents. Men came out of them as Freddy rode up, and pushed up around him, asking to have their fortunes told.

“Yes, I will tell them,” he said. “But one at a time. And not with you all crowding around. That tent there.” He pointed. “Is there a table there? Good. I will go there.”

So he dismounted and went into the tent and sat down at the table. The first man was short and slant eyed; Freddy thought him some kind of an Oriental. The others came up close to the door to listen, but Freddy shooed them away. Then when nobody could hear what he said:

“Listen,” he muttered. “I have the flying saucer plans. Do you want to buy them?”

“You have them?” the man exclaimed.

Freddy reached under his skirt and pulled out the tube. He took the cap off and pulled the roll of plans part way out and let the man assure himself that they were what he said they were.

“How did you get these?” the man demanded.

“I have known this house many years,” said Freddy. “There is a secret entrance. But what does that matter to you? Do you want them?”

“How much you want for them?” the other asked.

Freddy knew that such plans, if they were good, would be worth millions. He didn’t want to take money for false ones, even from an enemy of his country. But to hand them over for nothing, or for a small fraction of their value, would make the spies suspicious.

He shook his head. “Make me an offer,” he said.

The man said: “I must consult my associate.” He went to the door of the tent, and beckoned. Another slant-eyed man who might have been his brother came into the tent. They talked in a language which Freddy couldn’t even put a name to. It didn’t look like a consultation to Freddy; it sounded more as if the first man was giving orders to his associate. And after a minute the latter went away.

“We will pay generously for these plans,” said the first man, coming back to the table. “But you must understand that we do not have a large sum of money with us. We will have to arrange—” He broke off, as a car starter whined briefly and then merged into the roar of a racing engine. He hesitated a moment, then suddenly grabbed up the tube and shoved the table hard into Freddy, so that the pig went over backwards in his chair. And he dashed out of the tent.

Freddy picked himself up, shook out his skirts, and ran after him. The second slant-eyed man was at the wheel of a big car which was already in motion. The first man, with the tube in plain sight under one arm, was running beside the car, holding to the door handle. As he scrambled in, Freddy began to yell. “Stop him!” he shouted. “He’s stolen the plans! He’s got the plans of the flying saucer!”

All the men who were waiting to have their fortunes told suddenly ran for their cars. Two men with walkie-talkies were shouting excitedly into them, and other men, having seen that something was going on, from where they were watching, up the road or out in the fields, suddenly appeared and were dashing for their cars and motorcycles, which had been parked wherever there was a little cover behind walls and among bushes and trees. In two minutes they were converging on the road, down which rushed the stream of cars in pursuit of the thieves. In five minutes the landscape, which had been alive with running figures, was empty of men, and the roar of the speeding cars died away to the east. Freddy called to Cy, hopped into the saddle, and went back to the camp.