CHAPTER

17

Half an hour later Freddy was back in the cellar, but this time he was tied up tightly with clothesline. They hadn’t treated him too badly. They put him on an old mattress, and Penobsky assured him that they wouldn’t shoot him. “There’d be no point in it,” he said. “All we want is to get the saucer plans away from here without trouble. After that we will have no further interest in you. We’ll let you go. We’ll even give you back your pistol.”

“Ah, those disindegrinder?” said Smirnoff. “Was smart idea. How you train those animals they should play dead like that, eh?” He whacked Freddy good-naturedly on the shoulder.

Freddy was not deceived by their apparent friendliness, however. He knew that either of the spies would shoot him without thinking about it twice if it would be the slightest help to them. If they shot him now he would be much more bother to them than if they kept him prisoner and let him go later. There wasn’t a thing he could do.

As soon as they had gone upstairs he tried to work the ropes loose. But though he twisted and strained at them, the knots held. In adventure stories that he had read, the hero, when he was tied up, always found something sharp, a broken bottle or a bit of tin, that he could rub the ropes on until they frayed and parted. But though he rolled all over the cellar, Freddy couldn’t find a thing. At last, tired out, he rolled back on to the mattress and fell into an uneasy sleep.

When he woke again the floodlights were still on outside, but far away he heard a rooster crow, so he knew that it must be nearly morning. The rooster crowed again, and he thought that back in the Bean farmyard Charles would just be coming sleepily out of the henhouse to fly up on the fence and start the day. He was pretty uncomfortable. You try sleeping all night with your hands tied behind you and you will see why. To pass the time he thought he’d try to make up a poem.

“O calm indeed is the prisoner pig,

Remarkably calm is he,

He’s as merry and gay as the well-known grig—

(Whatever a grig may be.)

On the cold stone floor of his dungeon cell,

He does not sob and he does not yell;

To see him you’d think he was feeling swell,

As he smiles so gallantly.

“But pigs are brave, and pigs are bold,

With nerves as strong as steel.

When wounded in battle, so I’m told,

They never squeak or squeal.

They know no fear and they know no dread;

And where lions and tigers fear to tread

They rush right in. When they growl, it’s said,

Even elephants reel.”

Freddy repeated this aloud to himself, nodding his head with satisfaction. And a small voice said: “You’ve ‘been told,’ eh? And you’ve ‘heard it said.’ That’s hearsay, Freddy; that’s not evidence.”

Another voice said: “And I’ll bet that where you heard it said, was right inside your foolish head.”

“Give us the old growl, Freddy,” said a third voice.

“Hey, mice,” said Freddy, rolling over so that he could look toward the door, “how did you get back here? I thought you went with Uncle Ben in the caravan.”

“Sure,” said Eeny. “We were all waiting just at the edge of the Big Woods. We heard Cy coming, and we thought you’d be riding him. But you weren’t, and he told us that they’d caught you. So we came back. Come on, boys, get at those ropes.”

The mice swarmed over him, gnawing at the clothesline. Samuel was with them, but he did little work. He sat on Freddy’s chest, lecturing him on the folly of his arrangements for getting the plans. Freddy should have done this and he should have done that. “You ought to have sneaked up and got the plans and taken them down cellar before you pulled that switch,” he said. “You ought not to have turned Jinx loose in the dining-room till you were ready to go out the cellar door. You ought to—”

“Oh, shut up, Samuel,” Cousin Augustus interrupted. “You’re so smart, why didn’t you go up and get the plans yourself?”

“Well, I’d have done a better job. I say I’d have done a better job. We wouldn’t have had to risk all our lives coming back here again.”

“Golly,” said Eek, “these ropes sure are dry. Why don’t you go up in the kitchen, Samuel, and see if you can’t find some bacon fat to rub on ’em. Make ’em taste better.”

“I wouldn’t do this for anybody but you, Freddy,” said Quik. “Sets my teeth on edge.”

Pretty soon the ropes parted and Freddy sat up and shook himself. “Well, I’m certainly grateful to you boys for coming back,” he said. “I don’t think these people were going to shoot me—that would be foolish, because once the plans are taken away from here and on their way to some foreign country, I can’t do them any harm, and they’ll just disappear.”

“Yeah,” said Eeny, “and maybe they wouldn’t even bother to turn you loose. You could have stayed here till you dried up and blew away.”

“That’s true,” said Freddy. “But besides that, you may have done a big service to your country by coming back. Now maybe we can get the plans back for Uncle Ben.”

“You mean you’re going to try the same stunt again tonight?” Eek asked.

“No. I’ve got a better idea. You remember that Rendell? Tonight’s Friday night; that’s when he’s supposed to come. I’ve got to go down to the fairgrounds and see him. As soon as it gets dark I’ll make a break. You’d all better go out now and have Cy take you down to where the caravan’s waiting in the Big Woods. Then have him come back and wait at the end of the path. And tell Uncle Ben to stay in the woods till I get there.”

The mice were curious to know what Freddy intended to do, but he refused to discuss it. “You go on,” he said. “I’ve got a lot of thinking to do between now and dark. Go on; don’t bother me.” So they arranged the ropes to look as if Freddy was still tied up, and then they went.

It was a long day for Freddy with nothing to eat or drink. Nobody came down cellar, and the only people there were a couple of spiders who wouldn’t have anything to do with him. They evidently thought he was a Communist, and they wouldn’t talk to him but just sat up in their web and sneered at him. He tried to compose a few poems, but in spite of all the stories about poets writing masterpieces while starving in attics, he found that he couldn’t even string two rhymes together on an empty stomach. “Of course I’m not in an attic, anyway,” he said to himself. “I’m in a cellar. But I don’t see why that should make any difference.” And then he tried to make a rhyme out of that.

“A poetic young feller

Once lived in a cellar.

’Twas damp and rheumatic

So he moved to the attic,

Where the verses he scribbled

Were really much sweller

Than the rather too ribald

Ones done in the cellar.”

He had to repeat this out loud to see how it sounded, and of course the spiders heard it. One of them looked at the other and raised his eyebrows and said: “Really!” And the other just sniffed.

This irritated Freddy. “I wasn’t addressing you,” he said, “and I wasn’t asking for your comments.”

“I don’t see that there are really any comments that we would care to make,” said one spider. And the other said: “Unfortunate that there is no attic in this house.”

No one would blame Freddy if he had gone over and squashed both those spiders. Like most poets, he was enraged to have even his weaker efforts criticized. But he controlled himself. “I don’t know what you expect,” he said. “You can’t make verses when you’re suffering from hunger and thirst.”

“My dear fellow,” said the first spider, “we didn’t expect anything.” He paused a moment. “Not anything,” he repeated.

Freddy turned his back and tried to take a nap.

The day came to an end at last. Freddy didn’t wait until dark. He was afraid that if he did, it would be too late for what he had to do. He would just have to take a chance at being shot at when he ran out the cellar door. And that is what he did. As soon as the sun began to go down and the cellar windows to darken, he got up and pulled the switch so that the floodlights couldn’t be turned on, and then he hurried up the stairs, flung open the door, and ran for his life down the path to the back gate.

There was a startled shout from the back window, but no shots followed. Out the gate he tore and into Cy’s saddle; and then he was galloping off down the road toward the Big Woods.

The caravan was waiting by the side of the road. Freddy stopped only long enough to get from Uncle Ben the carton of ants, and the tube containing the second set of false plans; then with Jinx, mounted on the goat, beside him, galloped on toward Centerboro. In front of him on the saddle rested the carton containing the cannibal ants.

The fairgrounds were dark, and they pulled up just inside the gate and listened. Somewhere, at the far end away from the grandstand, an engine was ticking over quietly. It didn’t sound like a car.

“That’s our man,” said Freddy. “Keep back out of sight. I don’t think he’ll dare call the police. If it comes out what he’s trying to do tonight, he’ll be tried for treason.”

“You want me to wait here until you come back?” Jinx asked.

“Yes, you and Bill and Cy. If I have luck, I’ll be back before midnight. All right, Cy.” He reined the horse forward.

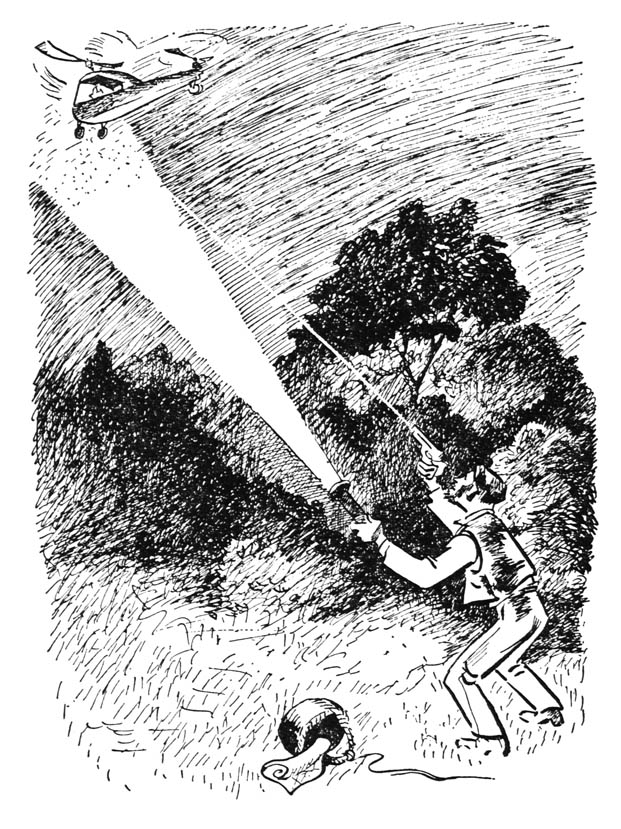

There were thick woods at the far end of the fairgrounds. Just before reaching them Freddy saw the helicopter. There were no lights on the machine, but the sky was still bright enough so that Freddy could see the outline of it, and the movement of the propeller against the sky. He rode up closer, until he could make out the figure of the man at the controls.

“Mr. Rendell?” he called.

The man leaned out. “Sorry,” he said. “I never take anybody up at night.”

“I don’t want to go up,” Freddy said. “Mr. Penobsky sent me here. He wants you to take this box with you tonight, along with what you are to pick up at his place.”

“Penobsky?” said Rendell. “I don’t know any Penobsky. You’ve got the wrong man, mister.”

Freddy dismounted and came up to the machine. He shoved the carton quickly in on the floor next to Rendell’s seat. “Penobsky didn’t have time to get in touch with you through Paul,” he said, “or to try to get a message to you. He told me to come straight here. Look, I know what your job is, and what that basket’s for,” he said, pointing to the one with a cord attached on the seat beside the pilot. “They’re waiting for you now. They weren’t sure when you’d start; Penobsky was afraid he’d miss you if he came himself.”

Rendell still hesitated, and Freddy decided that he’d better act at once. He reached in and lifted the cover of the carton. “O.K., Grisli,” he said. “This is the guy I want worked over. Let your boys go to work.”

The cannibal ants boiled up out of the box. Before Rendell could say any more they were in his hair and on his wrists and ankles, they were up his pant legs and coat sleeves, and walking down inside his collar. And they went right to work biting. Rendell gave a couple of yelps, his arms and legs jerked frantically, and then he was out of the helicopter, apparently doing some sort of a gymnastic dance that included rolling about and tearing off his clothes, as well as yelling at the top of his lungs.

Freddy clambered quickly into the seat. “All right, Grisli,” he called. “Good work. You can let the guy go now. Drop off the machine, all you soldiers, and rally on the carton. I’ll pick you up later. Take orders from Jinx.” He tossed the carton to the ground, and taking hold of the controls, sent the helicopter straight up in the air.

Freddy had had a pilot’s license for two years, but a helicopter is harder to fly than other planes, and he had had only a few hours’ experience in the air in one. But Uncle Ben had given him careful instructions, and so he did not have too much difficulty making the machine go where he wanted it to. Out in the open it was still not entirely dark. It was not yet ten o’clock either—the hour at which Penobsky had said he would put out the floodlights, so that Rendell could pick up the plans without being seen. Freddy took a few turns around the fairgrounds to get the feel of the controls, and then he practiced hovering. Fortunately it was a still night; he was able to stop, hover, and drop the basket within a foot of where he wanted it nearly every time.

He waited a while after he had heard the town clock strike ten, then he started for Penobsky’s. Everything went as he had planned. The house was dark, but as he flew over it, someone came down off the porch and waved a flashlight. Freddy circled round and hovered and let down the basket. When he drew it up the tube of plans was in it.

Now came the tricky part. Quickly he substituted the false plans for the real ones, then he dropped basket and rope, pretending to snatch at them and miss them as they fell at the feet of the man, who he saw was Penobsky.

The spy picked them up. “Come down, you clumsy fool!” he shouted. He held up the basket. “Come down and get it.” At the same moment he turned the beam of the flashlight momentarily on Freddy.

“Hey! It’s you!” he shouted. He dropped the basket and tugged a pistol out from under his coat. And Freddy opened the throttle so that the helicopter shot up and away. A couple of bullets ripped past his head, and then the house was far below and behind him, and he grinned happily. He had got back the real plans, and at the same time he had convinced Penobsky that he had them. There would be no more trouble for Uncle Ben. He’d be free to build his engine without being bothered.

A couple of bullets ripped past his head.

Back at the fairgrounds Cy came trotting out to meet the helicopter. “Jinx is rounding up ants,” he said. “They sure got spilled over a lot of territory when that guy went into his dance.”

“Did many of ’em get squashed?” Freddy asked.

“Not many. They’re pretty tough. There are some busted legs and sprained feelers, but they don’t seem to mind those any more than you or I would mind a stubbed toe.”

A minute later Jinx came up on Bill, and handed the carton to Freddy. He saluted. “All present or accounted for, sir,” he said.

“Where’s Rendell?” Freddy asked.

“After the ants got off him he ran off yelling,” Jinx said.

So they left the helicopter and rode back home.

When they reached the barnyard the caravan was standing by the barn. Nobody was around, but there was a light in Uncle Ben’s workshop.

“Look, Jinx,” said Freddy, “the plans are safe now, but we still can’t tell anybody. Until the saucer is built, I’ll have to keep out of sight. I’m still supposed to be in jail. Now’s the chance for us to take that trip. Let’s start right now. I’ll take the plans up to Uncle Ben, and you take this carton and go get the cannibal queen and take them back to the ant hill. Then get your saddlebags and meet me at the pig pen in fifteen minutes.”

He dismounted and ran up the stairs to the loft and plunked the tube down on the bench in front of Uncle Ben. The old man looked up without saying anything. Then he uncapped the tube, pulled out the roll of plans, and looked them over carefully.

“Good!” he exclaimed suddenly. He beamed at Freddy, put an arm across his shoulders and clapped him on the back. Then he spread out the plans on the bench, put weights on the corners, and began to study them. He seemed to have forgotten Freddy immediately.

Uncle Ben certainly never overpraised anybody, Freddy thought. And yet he was entirely satisfied. Uncle Ben’s “Good!” meant more to him than, from another man, a long oration, with flag waving and fireworks. He smiled happily as he went back down the stairs.

At the pig pen he got into his cowboy costume, and with his guitar slung over his shoulder, came out and swung into the saddle. He hadn’t lit a light, and had moved very quietly, but as he sat waiting for Jinx, a small hoarse voice down near the ground said: “Hey! You promised to take me. I say you promised to take me.”

“Oh, for gosh sakes!” said Cy disgustedly. “It’s that Samuel Jackson again.”

Freddy said: “Yeah.” And then he said: “We did promise to take him, Cy.”

Cy didn’t say anything, but he shrugged his shoulders so violently that Freddy’s hat fell over his eyes.

Freddy said: “Look, Samuel, instead of taking you on a long hard trip, wouldn’t you rather we went down right now and dug up your valuables, and put them in the bank where they’ll be safe?”

“No,” said the mole.

But after a minute, as nobody said anything, he said: “Yes, I’ll settle for that. If you remember how to find the things. But I bet you don’t—I say I bet you don’t.”

“Why, let’s see. No, I don’t believe I do. But Jinx will know. The ants that found the stuff told Jerry Peters, and Jerry told Jinx. Don’t you remember? Jinx gave you very careful directions. I remember hearing him.”

“Sure. Only you wouldn’t go then, and now I’ve forgotten them.”

“Well, here comes Jinx now,” said Freddy, and as the cat came trotting up astride Bill, he explained the situation to him.

“Why, sure, I remember,” said Jinx. “There’s a hole by the east gatepost, and you go along that tunnel for two minutes, and then you come to a fork, and you turn right—no, I guess you turn left, and then you—lemme see, now; you take the left fork—no, I guess it’s the right one, after all. And then you—no, no … oh, I don’t know, I can’t remember. Let’s ask Jerry; he’s the one that told me.”

So they went into the pig pen and opened the desk drawer, and asked Jerry. And Jerry couldn’t remember either. “Though there’s something in it about ‘twenty paces farther on.’ But I don’t remember farther on from what. We’ll have to ask those ants. Only—well, golly, I don’t remember which hill they came from.”

“You see?” said Samuel triumphantly. “I knew you wouldn’t remember. I say I knew you wouldn’t remember. You’ll have to take me.”

“All right,” Freddy said. “But you’ll have to ride in one side of these saddlebags. The basket’s no good—you’d bounce right out when Cy started to trot.”

So they set out, up the slope from the barnyard, and leaving the Big Woods on the left, on toward Otesaraga Lake. At the top of the hill overlooking the next valley they turned and looked back. Nothing could be seen of the farm, but from out of the blackness where it lay, a little speck of light marked where Uncle Ben was working away in the loft over the stable.

They turned and rode slowly down into the valley. And as they rode, Freddy slung his guitar around and after a preliminary twangle, struck into the song that they had sung on the road to Florida, so many years ago.

“Oh, the sailor may sing of his tall, swift ships,

Of sailing the deep blue sea,

But the long, long road where adventure waits

Is the better life for me.

Not the broad highroad that runs dead straight,

With never a loop nor bend,

But the narrow road, the gypsy road—

The road that has no end.

The road of adventure’s the gypsy road,

Where ghosts and goblins lurk,

Where rounding a curve you may see tall towers,

Or a sign saying “Dwarves at Work.”

Each one would sing a verse, while the others hummed an accompaniment. Sometimes it was a brand new verse, composed on the spur of the moment, or if the singer couldn’t think of anything, he repeated a verse from the old song, which by now had nearly a hundred verses. Then they would join in on the chorus, which went like this:

“Oh, the winding road is long, is long,

But never too long for me.

And we’ll cheer each mile with a song, a song,

A song as we ramble along, along,

So fearless and gay and free.”

Cy was the only one who didn’t sing. He had tried a few times, but the other animals always asked him to stop. Most horses are poor singers. It isn’t so much that they can’t carry a tune, as that they carry it off into a tuneless screeching where nobody could follow them, even if he wanted to. That left only Jinx, Bill, and Freddy.

Their voices blended pleasantly, but on the second chorus, Freddy thought he heard a fourth voice, softly singing a very capable, deep bass. He listened carefully. It was not Jinx, whose high wailing tenor was easy to distinguish. Nor was it Bill, whose baritone was true, but a good deal like a bleat. He glanced at Cy, but the horse’s mouth was closed.

The bass accompaniment grew louder. It was a fine, true tone, and gave some unexpected, but very pleasing twists to the harmony. Then suddenly Freddy looked around. And there was Samuel Jackson, his head sticking out of the saddlebag, his mouth wide open as he reached for a deep one. “Well, for goodness’ sake!” said Freddy.

He nodded encouragingly at Samuel. “Your verse,” he said.

And Samuel sang:

“Or a fleet of saucers from far-off Mars

Coasting in for a landing,

Or a group of animals from the farm

With Frederick Bean commanding.”

The others all turned and stared at the mole, and it wasn’t until he had started the second line that they resumed their humming accompaniment. Then they stood still, all facing Samuel, as they sang the chorus.

Then they began congratulating him. “Hey,” said Jinx, “why didn’t you tell us you could sing like that?”

“You must have had a lot of lessons,” said Bill.

“All moles can sing,” said Samuel. “And I did tell you. I say I did tell you. When I asked if I could go on the trip, I said I had a lot of songs and stories. But you never asked me any more about them.”

The animals looked a little embarrassed, and after a minute Freddy said: “You see, Samuel, we don’t know much about moles. We hardly ever see one. Did you know moles could sing, Jinx?”

“Didn’t know anything about them,” said the cat.

“Trouble with you barnyard animals,” said Samuel, “you don’t know much of anything about what goes on outside your own little circle. Cows and pigs and dogs and horses and chickens and goats—you just got a tight little club here, and folks that ain’t in it, you just don’t know that they exist. Take us moles singing. When we aren’t hunting, about all we do is get together and sing. There isn’t anything else to do underground in the evening. Our eyes aren’t very good, and so we don’t care to go sight-seeing. We’ve been singing here for a hundred years or more, and I bet you there isn’t an animal on this farm that even knows we’re here.”

“I don’t see how you can blame us for that,” said Bill. “If we don’t see you and we don’t hear you, how could we know?”

“Maybe you’re right,” said Samuel. “But after I told you—well, you didn’t seem very anxious to have me go along on this trip. You just think because you never knew a mole before, that he won’t be good company.”

“Look, Samuel,” said Freddy, “if we really hadn’t wanted you, we wouldn’t have let you come. We’re glad to have you with us. And, I’ll admit, we’re doubly glad when we know you have such a fine voice, because we like to sing, too. Is that right, animals?”

“Sure,” they said. “Sure.” And they all went up and shook hands with Samuel and congratulated him.

“O.K.,” said Freddy. “Now let’s get going. And have another song. How about “Down By the Old Mill Stream”? Got a good bass for that, Samuel?”

“Try me,” said the mole.

So Freddy started. “Down by the—” And the others came in: “—old mill stre-e-eam. Where I first met you-u-u—”

Samuel’s bass was magnificent. “Golly,” Freddy thought, “we’ve got a full quartet now. We can give concerts and probably pay all the expenses of the trip.” He turned and looked at Jinx with raised eyebrows (of course they were the painted gypsy ones that hadn’t been scrubbed off yet). And Jinx winked and nodded, and raised clasped forepaws above his head and shook them.

And so they went on, singing song after song, up around the east end of Otesaraga Lake. It got to be two o’clock, and three. Lights went on in lonely farmhouse windows, and heads were poked out, wondering where the lovely music was coming from. Deer and rabbits and woodchucks raised their heads to listen, and even porcupines, who are not a musical race, grunted appreciation.

But at last Freddy said he guessed they’d better get a little sleep. So they found a sheltered spot in a fence corner, and then they sang “Good Night, Ladies.” And when they’d all lain down and squirmed around until they were comfortable, Samuel sang a lullaby. He sang very softly, and by the time he reached the end of the second verse the others were sound asleep. So Samuel curled up in the saddlebag and closed his eyes and smiled happily. “Now,” he thought, “I’m one of the gang.”