“That’s why people make up these little stories, in

order to escape into them sometimes. You become

impatient with your life and so you find these

little places where you can move people around …”

(Tom Waits to Bill Forman, New Musical Express, 10 January 1987)

The first thing I asked Tom Waits when I met him in April 1985 was whether the “spent piece of used jet trash” in Swordfishtrombones’ “Frank’s Wild Years” had survived her husband’s torching of their San Fernando Valley bungalow.

Waits said Frank’s missus had been at the beauty parlour that evening but admitted that Carlos—her blind Chihuahua—might just have gone up in the “Hallowe’en orange and chimney red” smoke of the conflagration. He went on to explain that the song had mushroomed into a two-act musical that turned Frank’s micro-narrative into a far bigger “story about failed dreams.” The eponymous hero was now an accordion player from the tiny California town of Rainville, a man who’d gone off to seek fame and fortune in Las Vegas and beyond. “I would describe it as a cross between Eraserhead and It’s a Wonderful Life,” Waits said. “It’s bent and misshapen, tawdry and warm … something for all the family.”1*

Waits ran down the plot for me, sketching out a potted biography for Frank Leroux, who would later—in a Cajun/Irish switch—become Frank O’Brien. “When he was a kid, Frank’s parents ran a funeral parlor,” Tom told me. “While his mother did hair and makeup for the passengers, Frank played accordion. So he’d already started a career in showbiz as a child.” Waits described how Leroux went to Vegas and became a spokesman for an all-night clothing store; how he won a lot of money on the craps tables but was rolled by a treacherous cigarette girl; and how—despondent and penniless—he chanced upon an accordion in a trashcan.

At that time I had no idea that Waits’ father was called Frank, or that Frank’s Wild Years would partly be Waits’ attempt to make sense of his father’s artistic frustrations and dereliction of paternal duty. I assumed Frank was just Waits’ all-purpose dreamer-loser, an American archetype that he and Kathleen saw as the ideal cipher for their parable about “the business of show.”

Ever since his work on the unfinished Why Is the Dream So Much Sweeter than the Taste? and then on One from the Heart, Waits had wanted to produce something more substantial than a standard rock album. With Brennan by his side, the impetus to distance himself from his pop-rock/singer-songwriter contemporaries only grew stronger. Being hailed as Rolling Stone’s Songwriter of the Year for 1985 was gratifying, but Waits was determined to create something like a novel or a movie or an opera. Already Kathleen was introducing him to the work of avant-garde theatre director Robert Wilson.

But Waits and Brennan drew blanks as they touted Frank’s Wild Years round the New York theatre world. “The ritual around here is very well-established,” he told me. “If you’re coming in from some other place, well, you wait for a table.” Waits was also contending with a deeper prejudice, one stipulating that rock musicians should stay in their places. “Most people don’t want you to be able to do two things at once,” he said. “Either you’re a plumber or you play the violin.” Those words were spoken a year after my interview, as Waits and family prepared to leave for Chicago to start rehearsals for the Steppenwolf Theater Company production of Frank’s Wild Years.

Founded in 1974 by Gary Sinise, Terry Kinney, and Jeff Perry, Steppenwolf had launched the careers of such actors as John Malkovich, Joan Allen, John Mahoney, Martha Plimpton, and Laurie Metcalf—not to mention Sinise himself. After the company used a number of his songs in the Malkovich-directed 1984 production of Lanford Wilson’s Balm in Gilead, Waits met with Sinise, Kinney, and Malkovich in New York. In late 1985, the company green-lighted a three-month summer run for Frank’s Wild Years at Chicago’s Briar Street Theater. Kinney was set to direct, with Waits himself playing Frank. “We really landed in the right place after a lot of dead ends,” Waits said. “Kind of a garage-band-style theater, three chords and turn it up real loud.”

For the pit musicians, Waits booked the core of the Rain Dogs group minus Marc Ribot (who couldn’t commit to being away from New York) and Stephen Hodges (who never found out why he didn’t get the call). Joining Greg Cohen (bass, occasional horns), Ralph Carney (saxes), and Michael Blair (drums, marimba, glockenspiel) were Bill Schimmel (accordion and other keyboards) and—in Ribot’s stead—sometime Captain Beefheart guitarist (Jef) Morris Tepper.

Schimmel had been approached directly by Steppenwolf after accompanying Waits on the David Letterman show in February. “We had an elaborate rehearsal process for about six weeks, working it out together in a workshop situation,” he remembers. “We were doing the whole Brechtian thing and then breaking in the Vegas thing as well. We had to be ready to do fifteen bars of something that could have been right out of Vegas.” Fortunately the Frank’s Wild Years songs were, in the main, harmonically simple: to allow room for Kathleen’s dialogue to work over them, they had to be. “She was around a lot during the rehearsals, when it was on its feet,” Schimmel says. “A lot of those words were her words and she wanted to make sure they were mounted properly.”

For the Juilliard-trained Schimmel, about to turn forty, Frank’s Wild Years was the most rock-and-roll experience he’d ever had. “In many ways we were very unlikely rock stars,” he admits. “None of us looked like rock stars and none of us acted like rock stars. But all of a sudden we’re in this band and sort of becoming rock stars.” Schimmel says Waits was inspirational throughout the rehearsals. When the band had worked up and taped an arrangement, Greg Cohen would hand a cassette to Waits, who’d come in after rehearsing with the Steppenwolf actors. Concerned that the music might stagnate through nightly repetition, Waits urged the musicians to make deliberate mistakes. “He’d want more funny notes and he’d want tricky little train wrecks in the textures,” says Schimmel. “If we were getting a little too tight, he would be a little bit wary about that. He always wanted a bit of a rub in everything, and when we got that right he seemed to be relatively satisfied.”

Schimmel has never forgotten a nightly ritual enacted by his employer. Before each performance of Frank’s Wild Years, Waits would show up outside the theatre, park his yellow Chevy Citation on the opposite side of the street, and walk straight past the people lining up for tickets. Nobody, says Schimmel, ever recognized him. “He’d have his blues hat on and an old school bag that he carried,” Schimmel says. “He’d get out of the car very slowly, close the door, and walk past the crowd into the door … and they wouldn’t see him. He could do the Rasputin thing. Tom could make himself invisible, and that blew me away.” For Schimmel it was part of the mystery of Waits that he could somehow act his way into not being Tom Waits.

Schimmel also witnessed Waits unwind after his performances as Frank. “He would sometimes drive me home from the theater in the Citation,” Bill recalls. “And in the car he would start to free-associate. He was coming down after the performance, and he would start to free-associate poetically. I really enjoyed that.”

No theatrical production is complete without its share of friction and conflict. “You have to be a little foolish to do something like this,” Waits told me. “A play takes a lot of energy—emotionally, financially.” Just a few weeks before it was set to open, Terry Kinney resigned and handed the directorial reins over to Gary Sinise. Though no one ever explained the reasons for Kinney’s departure, clearly there was friction between him and Waits. Stepping into the breach, Sinise kept the show on track. “Gary has been great,” Waits said in a Chicago radio interview on 11 July. “He whipped it into shape and it’s been a lot of work, it’s been a great collaboration.”

Among those who came to see Frank’s Wild Years was Bill Goodwin, Waits’ drummer on Nighthawks at the Diner. “Tom was terrific in it,” Goodwin recalls. “He did this thing where he was supposed to be tap-dancing but he really just imitated a guy tap-dancing, and it was really effective. After the show I went backstage to see him and he wasn’t keeping the late hours anymore. His mom was there and his wife was there. He really looked well-rested and well-fed, and Kathleen seemed really nice.”

Reviews of Frank’s Wild Years were polite but not ecstatic. “The play, nearly three hours in length, could use some pruning,” wrote Rolling Stone’s Moira McCormick. In the New York Times, John Rockwell opined that “the writing is not sure enough to redeem the inherent clichés, as [Waits’] best concerts have done.” For all the keenness to break moulds, the production was “decent but conventional.” A “slightly awkward, actorish quality” persisted in the performances, “caught between cinematic realism and low-life stylization.”

Plans to rework the show with a view to a New York run were quickly shelved. “I just didn’t have the time to do the work the play would have needed,” Waits said. Instead, believing the songs were as strong as those on the two previous albums and seeing the opportunity to complete a kind of “Frank trilogy,” he decided to get Frank’s Wild Years on tape as soon as the Steppenwolf run ended. “Once the play was over, Tom said, ‘Well, why don’t we just record?’” Ralph Carney remembers. “So we ended up staying in Chicago a couple more weeks and recording the album.”

Waits being Waits, almost every song changed shape as he worked with the band at Universal Recording studios. Surviving demos of the songs make clear the radical metamorphoses that pieces such as “Temptation,” “Blow Wind Blow,” and “Yesterday Is Here” underwent. “In the stage play the music was a little more conventional,” Waits said. “I got a chance to work on it and push it around and stretch it and take it out of focus […] to flatten things out and push them to their limit …” Ralph Carney recalls Bill Schimmel being thrown by the rearrangements, unused as he was to such change-for-change’s-sake. In fact, Schimmel quickly intuited that recordings and live performances were different phenomena for Waits. “Tom knew that a record is a record and a show is a show,” he says. “The way he works, a recording has to be a mystical experience. And the songs had to be done differently to make a conceptual-sounding thing work properly.”

Ralph Carney, Oakland, 1991. (Kristina Perry)

Keen to instill freshness into the proceedings, Waits pushed the musicians out of their comfort zones. “He’d try things like giving me a marimba,” Ralph Carney remembers. “Greg Cohen went out and bought an alto horn, I bought a baritone horn, and Morris Tepper bought a cornet.” On the “bar-room” version of “Innocent when You Dream,” Carney played a barely detectable violin. “You never knew who was playing drums,” Bill Schimmel adds. “We all got a chance. And a lot of times when you listen to the textures, you don’t know who’s playing what.”2*

A couple of weeks into the sessions, Waits called Marc Ribot and asked him to come to Chicago. He also flew Francis Thumm and Larry Taylor in from LA to work on certain tracks. “Francis showed up and offered suggestions,” says Schimmel. “Not only did he have good ears for what he was doing but he knew his rock and roll.” For Morris Tepper, Ribot’s arrival was humiliating; Carney remembers the Beefheart alumnus waiting in his hotel room to be called while Ribot added typically gnarly fills to “Hang On St. Christopher” and “Way Down in the Hole.” In the end Tepper appeared on four tracks, playing alongside Ribot on both “Temptation” and “Telephone Call from Istanbul.”3*

Given that we can’t see the Steppenwolf production of Frank’s Wild Years—some of the early performances were videotaped but have never been commercially available—we have no choice but to take the album for what it is: a collection of discrete tracks that either hang together or don’t. Since we lack the theatrical context of their onstage deployment, striving to make sense of the songs as a narrative thread is, frankly, unrewarding. “[Frank] dreams his way back home and then kind of relives these things,” Waits said by way of explication. “He went out on the road with an idea that kind of unraveled for him and became kind of a nightmare, so that’s kind of the gist of it.” But he conceded that Frank’s Wild Years wasn’t “complete[ly] linear … it left-turns and then it shifts around a little bit.”

If the album had a central theme, it was that of dream and fantasy. Just how much of Frank O’Brien’s experience was real and how much imagined? Was he just fantasizing, as in the braggadocio of “Straight to the Top,” or were these events actually happening? “Everything is made from dreams.” “You’re innocent when you dream.” “Please wake me up in my dreams.” “All our dreams come true/Baby up ahead.” On “I’ll Take New York” Frank was going to “ride this dream to the end of the line.” “Frank’s Theme” counselled us to “dream away the tears in [our] eyes.” On the penultimate “Cold, Cold Ground,” “Times Square is a dream …”

Frank’s Wild Years started with one of its most accessible tracks, and one of only two songs on the album with an identifiably R&B feel to it. “Hang On St. Christopher” featured Bill Schimmel pounding a Hammond organ’s bass pedals with his fists, the effect creating a murky bass line that anchored the song’s twisted R&B groove. “It was the right percussive sound,” Schimmel says. “You almost didn’t need drums on the track.” Essentially a song of escape—Frank fleeing Rainville in a precarious junkheap and hoping to reach Reno in one piece—“Hang On” rode the 4/4 groove as Waits barked his bullhorn vocal over squawking horns and Ribot’s glassy vibrato guitar. “I think it moves along rather well,” Waits reflected. “Kind of mutant James Brown.” Waits had started using bullhorns—crowd-controlling megaphones—after Biff Dawes bought him one from Radio Shack as a birthday present. Mainly, he said, it was just to “get my voice to sound like it sounded at the bottom of a pool […] to tamper with the qualities it already has.” He said he was “sick and tired of the way I sound” and wanted to make his voice “skinnier” so it would fit in the song and allow more room for non-vocal sounds. To this day the bullhorn remains an ever-present in Waits’ musical toolbox.

Hot on the heels of “Hang On,” the locomotive groove of “Straight to the Top (Rhumba)” faded in with Michael Blair’s rumbling congas and Larry Taylor’s thumping, Bill Black-style bass. Blowing over them like a train-whistle was Ralph Carney, blasting two saxes simultaneously à la Rahsaan Roland Kirk. “I loved Kirk and what he did was amazing stuff, but what I was doing was nothing compared to that,” Carney says. “I was just messing around and put two horns in my mouth, and Tom said, ‘Hey, what’s that? Do that!’” Consciously or unconsciously, the song referenced One from the Heart with its Vegas/Rat Pack bravado.

“Blow Wind Blow” told a more honest story, Frank consigning himself to the gales of fate after a dalliance with a married woman. The surreal lyric and creepy fairground instrumentation (banjo, pump organ, glockenspiel) only enhanced the sense of disorientation. The track was also an early instance of Waits switching voices mid-song, ascending from his standard grainy growl to a strangely moving sub-Caruso timbre that conveyed Frank’s genuine distress. “You always work on your voice,” Waits said. “You want to be able to make turns and fly upside down— but not by mistake. You want it to be a conscious decision, and to do it well.”

Waits also tried new voices for “Temptation,” flipping from falsetto to an impassioned bel canto yodel as our hero succumbed to the charms of the cigarette girl. From its inauspicious demo start, the song had been transformed into a slinky dance number, with vocal lines wonderfully reworked by Kathleen Brennan. “That one started out real tame,” Waits admitted. “I added a bunch of stuff to it, and it started to swing a little bit. Now it sounds practically danceable to me.” Complete with sleepy Cuban horns, it is one of Waits’ greatest tracks, at once sexy and harrowing.

With the “bar-room” version of “Innocent when You Dream,” Waits pulled us into the smoky snug of an Irish pub. Coming out of “Temptation,” the song touched on the pain of loss and wallowed in the sort of sentimental bellowing he might have heard in County Kerry or on the John McCormack records his father-in-law played. The chorus posited the intriguing idea that in waking consciousness we’re somehow guilty or furtively dishonest—that only in our unconscious are we truly innocent.

With its stiff Schimmel accordion and intermittent baritone-horn farts, the gruff polka of “I’ll Be Gone” recalled “Rain Dogs.” Frank’s resolve was back up and running as a cock crew and a new dawn beckoned. The marimba appeared for the first and only time on the album as Morris Tepper supplied single-string Beefheart guitar lines. “[It’s] kind of a Taras Bulba number,” Waits explained. “Almost like a tarantella. Halloween music … from Torrance.”

“Yesterday Is Here” had begun life as a Tin Pan Alley ballad that would have been a shoo-in for One from the Heart. With Kathleen’s help, Waits transformed it into something like a spaghetti-western “House of the Rising Sun,” playing doomy Morricone guitar with only Larry Taylor’s sparse bass for company. Once again Frank was gloomy as he bid farewell to a woman. The road was “out before me” as he split for New York City.

Waits used Optigan and Mellotron on the spectral lullaby that was “Please Wake Me Up,” the third consecutive Waits/Brennan composition on Frank’s Wild Years. He sang the wistful lyrics in an airy Rudy Vallée tenor, sounding like a 78 rpm ghost on a cob-webbed Victrola, and the Optigan returned for a waltz-time coda.

Side One of the original vinyl release finished with “Frank’s Theme,” the most overt statement yet of our hero’s feckless escapism. Waits urged us to dream away our tears and sorrows and goodbyes, accompanying himself on a wheezy pump organ. “The pump organ really has lungs,” Waits said. “It actually breathes. I think I like the physical action of playing it, the sound it makes. It’s always a little sour, always a little off.”

The feel of “More than Rain,” at the start of Side Two, was more Montmartre than Manhattan. Frank was truly in the dumps on this chanson of alcoholic remorse. Though it featured Michael Blair on orchestra bells and Francis Thumm on prepared piano, it was Bill Schimmel’s swirling accordion that dominated the track. “He plugged me into a Leslie Twin-Cat, which is not an easy thing to do,” Schimmel says. “We worked half a day to get that sound, and he wouldn’t stop until we got it. We had to wire me up. I had wires between my knees. It looked like an execution.”

“Way Down in the Hole,” with Frank stumbling on a ranting preacher at a revivalist meeting, was minimalist gospel-blues: shakers, upright bass, and double-tracked horns, plus a brilliantly flinty solo by Marc Ribot. Waits’ fascination with rabid Bible-belt evangelists was like a missing link between John Huston’s 1979 movie of Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood and Nick Cave’s 1989 novel And the Ass Saw the Angel. Later used as the title song for cult TV series The Wire, it gave voice to the scary fundamentalist idea that the best we can do is repress evil rather than free ourselves from it. “We wrote that one real fast,” Waits said. “It was practically written in the studio. Checkerboard Lounge gospel.”4*

Following “Way Down” with the pub-singer reprise of “Straight to the Top” was a minor stroke of genius. Frank had become a down-at-heel sub-Sinatra, a supper-club hack; the idea of this man being anywhere “where the air is fresh and clean” was faintly absurd. Redeeming the track were Schimmel’s sublime cocktail piano and Carney’s fluid tenor solo. “Waits was definitely anti-jazz by this point,” Carney says.5* “But I got to be a little more jazzy on this one. I did a Johnny Hodges kind of thing.” And, of course, one could detect a sincere admiration for Sinatra’s phrasing in Waits’ vocal. “It’s a secret dream to work the big rooms,” he quipped to Rip Rense. “To get in there and work the Stardust, you know? Make it stick.”

From the “Straight” reprise, the album slid seamlessly into the drunken Buddy Greco nightmare that was “I’ll Take New York.” Inspired by the declamatory drunks he’d witnessed in and around Times Square, Waits became a demonic Ethel Merman, backed by seasick sax and pump organ.“[It] frightened me a little bit, especially toward the end when the ground starts to move a little bit,” Waits confessed. “[It’s a] guy standing in Times Square with tuberculosis and no money; his last postcard to New York.” The song eventually petered out amidst a welter of coughs.

Of all the songs on Frank’s Wild Years, “Telephone Call from Istanbul” sounded the most like an outtake from Rain Dogs. Again the track was minimal, built simply out of drums, banjo, and muted grunge guitar. With its bizarre lyrics, it begged the question whether it was really part of Frank’s story or merely slotted in to make up the numbers. Waits’ slashing Farfisa organ took us into the fade in fine style.

The album’s last two songs were recorded not in Chicago but some weeks later at LA’s Sunset Sound. Playing mariachi-style accordion on both “Cold, Cold Ground” and “Train Song” was David Hidalgo of the great Mex-Angeleno band Los Lobos, a favourite of Waits.’ “I’m looking toward that part of music that comes from my memories,” Waits said of the songs’ Spanish flavour. “Hearing Los Tres Aces at the Continental Club with my dad when I was a kid.” “Cold, Cold Ground” hadn’t featured in the Steppenwolf show and was written as an afterthought in LA. A song of retirement and resignation, the simple strummed ballad had Frank heading home with Times Square behind him and only death ahead. In some ways, though, the song was Waits’ trailer-trash picture of the rural haven he would eventually seek in northern California.

“Train Song” was Frank’s Wild Years’ very own “Anywhere I Lay My Head,” sung with the same ravaged emotion as that epilogue to Rain Dogs. Did Frank perhaps never get any further than East St. Louis? On this song of awful remorse, which opened with a faint melodic echo of “Ruby’s Arms,” it was hard not to think so. “[It’s] kind of a gospel number,” Waits said. “Frank is on the bench, really on his knees, and can’t go any further. At the end of his rope on a park bench with an advertisement that says ‘Palladin Funeral Home.’” As if he couldn’t bear to end the record on such a bleak note, Waits stuck a second reprise at the end of the record—essentially the bar-room “Innocent when You Dream” with the drunken singalong removed and Waits’ voice once again a ghostly noise emanating from an ancient 78.

Frank’s Wild Years wouldn’t see the light of day until almost a year after the Chicago recordings. When it did appear, it instantly asked a lot of Waits’ fans. The sound of a man radically out of step with eighties rock, the album signed off on the adventures of Frank Leroux/O’Brien while clothing them in Waits’ most extreme music to date. “Somehow the three [albums] seem to go together,” Waits said. “Frank took off in Swordfish, had a good time in Rain Dogs, and he’s all grown up in Frank’s Wild Years. They seem to be related—maybe not so much in content but at least in terms of being a marked departure from the albums that came before.” Most strikingly, perhaps, the songs Waits and Brennan had written about this archetypal American Quixote were mostly Latin and/or European in feel: there was no rock and roll here and precious little R&B.

Perhaps the real point about Frank’s Wild Years was its theatricality. “[These] are really songs about performance,” I wrote in my NME review of the album. “From the pulpit declamations of the preacher via the drinking-song roar of ‘Innocent when You Dream’ to the louche Sinatra hallucinating Las Vegas, they make up a rogues’ gallery of performing alter egos.” Indeed, Waits made clear the connection between his new music and his burgeoning sideline career as an actor, telling Rip Rense his movie experience had helped him “to write and record and play different characters in songs without feeling like it compromises my own personality …” Where formerly he’d felt compelled to inhabit his own music, Waits knew he could now separate himself from his own songs. “Before, I felt like this song is me,” he said. “I’m trying to get away from feeling that way, and to let the songs have their own anatomy, their own itinerary, their own outfits.”

Fittingly, Waits deferred the release of Frank’s Wild Years in order to undertake another film role. One of his Beat-era heroes, photographer and filmmaker Robert Frank, had collaborated with writer Rudy Wurlitzer on a screenplay about a young New York musician who sets out to find—in the words of David Johansen’s character—“the best goddamn acoustic guitar maker in the country.” Both men wanted Waits in the film, which was to be called Candy Mountain. The Swiss-born Frank had made his name with The Americans, a book of black-and-white photographs taken on a coast-to-coast road trip in the mid-1950s. An attempt to “see” America for what it really was—to see it as the Beats saw it—the eighty-three images subverted the country’s self-satisfaction, stripping away the Norman Rockwell veneer of the Eisenhower era. Looking at the photographs today is tantamount to looking at Tom Waits’ America: a place of pathos and inequality, Edward Hopper’s smalltown diners and gas stations bled of colour. “I think he changed the face of photography forever with that little Leica he used,” Waits said of the book.

After the 1959 publication of The Americans, Frank had all but given up photography to make films, starting with his short Beat documentary Pull My Daisy. Shot on a handheld 16-mm camera in a New York loft, with manic narration by Jack Kerouac, the film captured Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and friends riffing and sparring for the benefit of a young Swiss bishop and his wife and sister. By 1972, when the Rolling Stones hired him to make a documentary about their debauched American tour of that year, Frank was a cult figure in the art world of downtown New York. “He takes a really romantic position,” Rudy Wurlitzer said. “The old-fashioned artist who worships at the altar of total self-expression. And he protects his myth at any cost.”

An altogether more diffuse and murky portrait of the Stones’ milieu than the Maysles brothers’ 1970 film Gimme Shelter, Frank’s Cocksucker Blues—with its scenes of fellatio and shooting up—riled the group enough for them to veto its release. For years the film was shown only five times a year, and then only when Frank himself was present. Waits’ love of the Stones helped him bond with Frank when the two men first met in New York in 1984. Frank subsequently shot Waits for the back cover of Rain Dogs and thought of him for the small part of Al Silk in Candy Mountain. “It’s an odyssey about someone in New York searching for someone,” Waits said of the film. “I hesitate to say what it’s really about, I doubt if it would be … you know, it’s Robert’s film. I’m just in it.”

Shot in Manhattan, upstate New York, and Canada in the late fall of 1986, Candy Mountain was, by Frank’s standards, a big-budget production at $1.3 million. Wurlitzer, who’d written the screenplays for Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid and Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop (both featuring rock stars), had scripted this strange road movie with one eye on involving as many musicians as could be funnelled into a two-hour picture.6* Alongside Waits there were cameo roles for Dr. John, David Johansen, Leon Redbone, and Joe Strummer, as well as for such obscure figures as Arto Lindsay and Mary Margaret O’Hara. There was even a role for Jim Jarmusch, while Hal Willner oversaw the music and hired both Michael Blair and Ralph Carney to perform it.

Though Waits was only in Candy Mountain for a few minutes, he made the most of his scenes as a character who was temperamentally his own antithesis. A self-made, golf-playing millionaire, Al Silk refuses to divulge the whereabouts of his reclusive guitar-maker brother and urges his young visitor (Kevin O’Connor) to abandon his quest. “You should be playing golf,” he counsels as he brandishes an absurdly long cigar. Smashed on Jack Daniels, Waits bawls the old Irish ballad “Once More before I Go” before adjourning to an upright piano and singing through cupped hands. Later he reappears in a comically florid dressing gown and entrusts an old Pontiac T-Bird to Julius, who heads on towards Niagara Falls in it.

Candy Mountain was creaky and laboured; neither Frank nor Wurlitzer appeared to know what they were trying to say in this unconvincing anti-grail film. Julius was an unsympathetic hero, and none of the characters he encountered—barring the bizarre father-and-son duo of Roberts Blossom and Leon Redbone— was remotely compelling. “Robert sabotages himself a lot, and out of that comes his aesthetic,” Wurlitzer said in Frank’s defence. “He purposefully creates a sense of chaos, and that creates a lot of stress in the people around him.”

There was less chaos in Waits’ subsequent movie project, which—like much of Candy Mountain—was shot in upstate New York. This time, moreover, the budget was Big Hollywood, with starring roles for Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep. Cotton Club screenwriter William Kennedy had adapted Ironweed, his own Pulitzer-winning novel about alcoholic bums in 1930s Albany, for Argentinian director Hector Babenco, then flush with the success of 1985’s Kiss of the Spiderwoman. Filming in the late winter and spring of 1987, Waits was given the sizeable role of Rudy the Kraut, a gangling simpleton we encounter at the very start of the film. “It’s all about […] alcohol, baptism, and redemption,” Waits said of Ironweed. “It was a good experience for me.”

For Babenco, Ironweed was about “a collective soul, anonymous vagabonds … the courage and beauty of people we don’t usually think of as having deep and complex emotions.” For Waits it was almost as if Babenco had transposed “On the Nickel” or “Tom Traubert’s Blues” to the big screen. Nicholson was Francis Phelan, an ex-baseball player haunted by the deaths of his infant son and of a strike-breaker he’d accidentally killed as a young man; Streep played his companion Helen Archer, a sometime concert pianist fallen on hard times. Waits’ Rudy was by turns a goofy sidekick to Phelan and a kind of surrogate son to the couple. “The character for me was more like a little kid, you know,” Waits reflected. “[But] he was like a middle-aged man, you know.”

“He looked like any moment he might break at the waist or his head fall off his shoulders on to the floor,” Nicholson said of Waits’ Rudy. “I once saw a smalltown idiot walking across the park, totally drunk, but he was holding an ice cream, staggering but also concentrating on not allowing the ice cream to fall. I felt there was something similar in Tom.”

If Rudy was close to typecasting, Waits had figured he was no more than “a dark horse” for Ironweed. Bit parts in Coppola’s films and a co-lead in Jarmusch’s indie pic had hardly made him a household name. Preparing for the audition in New York, he had the sudden bright idea to stick a piece of toast and an old toothbrush in his shirt pocket: details he was convinced bagged him the role, especially since he was competing for it with both Dennis Hopper and Harry Dean Stanton.

Waits’ initial appearance in Ironweed was a defining one. The first thing Phelan saw was the pair of spats on Rudy’s feet; as his gaze rose he took in Waits in a grey pinstripe suit, topped off with a fancy yellow check waistcoat. “I-I got the whole outfit!” Rudy cackled with boyish glee. But there was a stinger in his tale: he’d just come from being diagnosed with cancer at the hospital (“first thing I ever got!”). Shuffling and shambling and sticking out his arms, Waits’ body language as Rudy was superb. Yet he was never entirely comfortable in the role, his nervousness in Nicholson’s presence almost palpable. “I have somebody that helps me out privately a little bit,” he admitted. “You know, I was very nervous about it and I thought I needed a shot in the arm.”

Neither Nicholson nor Streep made Waits feel uncomfortable for a second. He instantly admired these very different actors, Nicholson for his mischievous humour, Streep for her focused intensity. “Jack makes you look good when you’re with him,” he said. “He’s not picking your pocket, never grandstanding, not trying to eclipse the people he’s with. He’s trying to make himself small.” Streep’s “preparation and commitment and concentration within the characters” were, Waits said, “devastating.” He paid close attention to the way the two stars put together their characters. It was, he said, “like they build a doll from Grandmother’s mouth and Aunt Betty’s walk and Ethel Merman’s posture, then they push their own truthful feelings through that exterior.”

Waits learned as much from Nicholson offscreen as he did from watching him on camera. If anybody could teach you how to survive fame, he thought, Joker Jack could. He was the Keith Richards of actors. “People get frightened that success is going to take them out of life,” Waits said. “Life will only be something you can get through the mail. But Jack … just stays in there, being himself. He’s a good ad for success.” It helped that Nicholson was a music buff, regularly regaling cast and crew with mix tapes of songs by Billie Holiday and Robert Johnson.

If Ironweed was firmly in the tradition of middlebrow Hollywood compassion, the performances brought Kennedy’s compellingly bleak vision of poverty to life. “Until now I’d always thought that being a hobo was like running away from home,” Waits confessed. “[It was] letting your beard grow, eating out of cans in hobo jungles under a railroad bridge …” The reality—especially of alcoholism—was somewhat different. Indeed, Waits’ own drinking went unremarked amidst the general imbibing that took place on set. He was, he claimed, “forced to drink against my will … everybody was told, ‘’Cause it’s part of the story.’”

Wrapping Ironweed in late May, Waits could look back with some satisfaction on a growing movie CV. Despite its commercial failure, Babenco’s film was a bigger break for him than Down by Law, putting him on the mainstream Hollywood map as a character actor. “I think any artist who knows himself knows he functions best within his own parameters,” says Bill Schimmel. “Tom seemed to have the right balance between art and rock and roll, and he was the actor who was one step away from it—the fourth wall. On one level he seemed totally immersed in the part, but on another level there was a part that was a little disassociated from it.”

The extreme cold of Ironweed’s location shoot in Albany may have had something to do with Tom’s and Kathleen’s decision to return to California as soon as the film was finished. The climate alone did not explain the decision, however. “I wasn’t well-suited [to] the temperament of that town,” Waits said of New York in 2006. “I need something that’s a little more … not as volatile.” The city, he said, made him develop Tourette’s Syndrome: “I was blurting out obscenities in the middle of Eighth Avenue.” Waits told David Letterman that he was “treated better” in California. “I think Tom had got New York out of his system,” says Bill Schimmel. “I think he’d got what he needed. I just sort of imagine him on the open road like Harry Partch, with his thumb out. I don’t see him as a subway person. He just struck me as a person who functions better with space around him.”

In the late fall of 1987, Waits and wife returned to the area of Los Angeles in which he—and they—had formerly lived. Moving back to Union Avenue, they were once again living near his father, who was still teaching at Belmont High. For Waits it was a genuine community, a world away from the white middle classes on the West Side. “I’m more interested in these types of things … these people, I guess, in these neighborhoods,” he told Snowblind author Robert Sabbag, adding that he sometimes got recognized in the area as “Frank’s boy.” Memories of travelling through Mexico as a kid were triggered by the area in question. “The music down there was never an event, it was always a condiment,” Frank’s boy reminisced to Francis Thumm. “Where I live in LA I go down to the liquor store and there’s a guy standing on the street corner with an accordion and a guy with an upright bass.”

Back on his home turf, Waits’ family life became ever more important. “I’m beginning to create a world for myself that I can live in,” he said, before adding quickly that “I’m not happy or anything like that … I mean, I’m happy for a minute and then most of us are manic-depressive.” Behind the scenes Waits continued his on-off affair with alcohol, never quite able to shake it off. “Am I still a drunk?” he said to NME’s Sean O’Hagan. “I have a little sherry before retiring, sure. When I’m writing I’m usually pretty clean. I don’t think it’s alcohol that makes the music come out. It’s hard to tell. Sometimes alcohol massages the beast, sometimes it doesn’t.”7*

“Beginning to create a world for myself that I can live in”: return to Union Avenue, late 1987. (Art Sperl)

As happy as he was to be home in LA, Waits already had one eye on getting away from it all. A long-harboured fantasy of sitting on a porch in the back of beyond continued to hold sway for him. Used to “a certain gypsy quality,” he was “moving towards needing a compound” while “operating out of a storefront here in the Los Angeles area.” As if quoting from “Cold, Cold Ground,” Waits pictured himself beside a “briar patch” in Missouri, “a place where everything I drag home I can leave in the yard.” He was still two years shy of forty.

Come the summer, Waits geared up for the belated release of Frank’s Wild Years and for his first tour in two years. With Kathleen’s urging, furthermore, plans were made to shoot certain dates for a concert film. “I’d get home from the road and I wouldn’t have any pictures of the band or anything,” Waits reflected. “We’d talk about it like something that didn’t really happen. It was the first time we pursued pulling it together.” Chris Blackwell agreed to bankroll the project, installing Nic Roeg’s son Luc as the film’s producer. Ironically it was a noted TV-ad director, Chris Blum, whom Tom and Kathleen approached to direct the film. Blum had shot several TV spots for Levi-Strauss and helped develop the company’s memorable campaign for 501 jeans. Blum quickly agreed that it was imperative they conceive something quirkier than the standard in-concert document, working in a subplot about a ticket-usher who falls asleep in a theatre and dreams that he’s hit the Big Time (the film’s eventual title).

The release of Frank’s Wild Years necessitated a splurge of interviews, a ritual Waits was starting to find as taxing as touring. “I’ve been asked all these things before,” he told one interrogator as he sat in his beloved local diner the Traveler’s Café in January 1988. “If I sound a little like I’m watching the clock, it’s because I’ve been asked every one of those questions. I’m just being honest with you.” Behind the fatigue lay a deepening mistrust of the media. “I see the way a lot of people talk to the press,” he said. “To me it’s a bit like talking to a cop.” To Waits, the relationship between artists and the media had become unhealthy, with journalists reducing art to something knowable and commodifiable and artists obliging by fitting in with the media’s precepts. In his own way, Waits was holding fast to Beat ideals of bohemian purity, of not being defined and pigeonholed for painless consumption. Linked to his unease was Waits’ belief that the connection between an artist’s life and his work should never be presupposed; that any sane songwriter should refrain from representing his life in his music and instead conceal it. For him, Frank’s Wild Years was itself a kind of masquerade of personae that refused to reveal the “truth” about their creator. “Usually you hide what everything represents,” he stated. “You’re the only one who really knows.”

Waits particularly resented the way his old seventies persona was still hauled out by the media as a gauge of who he was. For all that he’d successfully deconstructed the “Beat wino” persona of his seventies albums, not everybody chose to notice. He bemoaned the fact that America hadn’t caught up with Europe’s embrace of his changes. “Here I have a lot of people who’ve been listening to me since 1972,” he sighed. “They want me to come out unshaven, drink whiskey, and tell stories about broken-down hotels.” He explained that he was trying to return to the freedom and primitivism of the child’s imagination—to unlearn the stylistic tropes of his act and the reflex actions of his hands at the piano. He cited Kathleen as someone who was “very unself-conscious, like the way kids will sing things just as they occur to them.”

Waits told NME that he’d got more “angry” and “fractured” with Swordfishtrombones, the subsequent records following suit and building on the risks he’d taken with it. What he particularly relished about his post-Asylum sound was its brokenness, the fact that it sounded unfinished. “If it’s too beautiful, too produced, I back off a little, start getting intimidated,” he said, citing the Pogues, the Replacements, and Alex Chilton as kindred creative souls. “Keith Richards had an expression for it that’s very apropos,” he said. “He called it ‘the hair in the gate.’ It’s like when you hear music ‘wrong’ or when you hear it coming through a wall and it mixes in—I pay attention to those things.” (Richards’ expression derives from a movie term referring to hairs or other objects getting into the “gate” of a film projector and thus appearing on screen.)

Asked what he might do next, Waits said he wanted to “try and do something with a much harder edge, something with more abandon.” He planned to unleash his pent-up rage at the world and call the album The World I Hate to Live In. “I get angry about some of the things I see … but I never say anything about it,” he grunted. “I think next time I will.” (Little did anyone know almost five years would elapse before his next album appeared.) Waits claimed he’d even been listening to “a lot of this rap stuff,” not least because it was unavoidable in a neighbourhood where souped-up jeeps blasted it from ginormous woofers. Like Neil Young, Waits resisted the impulse to be reactionary, embracing the threat from the upcoming generation and the “vitality” of this new urban form. The recent release of NWA’s incendiary Straight Outta Compton had shifted hip hop’s axis to the West Coast, and Waits loved it.

Though his music was a million miles from NWA, Roy Orbison had long been an idol of Waits.’ When T-Bone Burnett asked if he would take part in a “Black and White Night” to celebrate Orbison’s life and music, Waits put aside his usual disdain for Live Aid-style cronyism and agreed to join Bruce Springsteen, Elvis Costello, Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, k. d. lang, J. D. Souther, and others at the Coconut Grove in LA’s legendary Ambassador Hotel. Waits’ soft spot for Orbison dated back to the almost spooky effect of hearing the Texan’s freakishly beautiful voice through the airwaves as a teenager. At the Coconut Grove on 30 September, Waits remained for the most part in the shadows, supplying low-key guitar and organ as Springsteen and friends flanked Orbison. When the latter died just a year later, Waits wrote that his dreamy songs were “more like dreams themselves, like arias … he was a rockabilly Rigoletto, as important as Caruso …”

“It was definitely an evening where every ounce of ego was checked at the door,” k. d. lang told me. “And it was amazing, because you had really diverse people there. We were like disciples in a way. We were all very quiet and very focused on doing our jobs.”

A week after the Black and White Night, Waits kicked off his fall/winter tour. With ever-presents Cohen, Carney, and Blair augmented by Marc Ribot and new accordionist Willy “The Squeeze” Schwarz, the itinerary began in Canada with three consecutive nights at Toronto’s Massey Hall. Waits approached the tour with his usual antsiness. He detested the conventional stage setup for rock shows, the way the instruments and amplifiers were arranged, the wires winding round everything like the band was in a hospital ward. “I’m trying to put together the right way of seeing the music,” he said. “I worry about these things. If I didn’t it would be easier.”

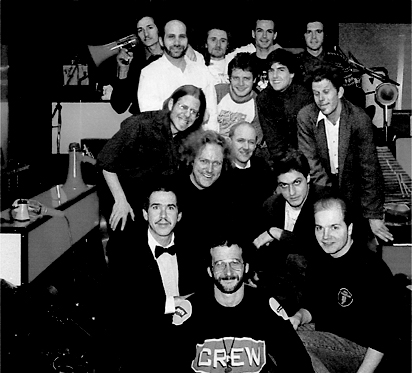

Big Time band and crew, November 1987, including Willy Schwarz (bow tie), Michael Blair (frizzy hair), Ralph Carney (leaning, demented grin), tour manager Stuart Ross (top, beard), Greg Cohen (with megaphone), and Marc Ribot (in front of Waits, intense stare). (Courtesy of Ralph Carney)

To ensure that the “concert film”—working title Crooked Time—bore no resemblance to any earlier example of the genre, Chris Blum worked with lighting designer Darryl Palagi on a stage concept based around a series of light boxes. “The original stage set started out as a junkyard,” he explained. “We had an idea for these huge plexiglass signs, like the ones you see in LA’s Koreatown—back-lit, primary-colored.” Palagi simplified this idea, giving each band member a different box. “Even though they’re supplemented by other sources, we wanted to give the impression that they were the only light sources,” Blum said. “The attempt was … to have things look non-art-directed.”

Drawing predictably on a pool of songs from “the Frank trilogy” but intermittently dropping in such old chestnuts as “Tom Traubert,” “Christmas Card,” “Jersey Girl,” “Jitterbug Boy,” and “I Wish I Was in New Orleans”—plus a crazed version of James Brown’s “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag”—Waits pulled out all the stops in an effort to stimulate, provoke, and entertain. Flipping from one persona (slimy cabaret MC in sunglasses/tux/pencil moustache) to another (folk troubadour in waistcoat and porkpie hat), he drew on his Steppenwolf experience to turn the in-concert rock experience into something meta-theatrical.

The US leg of the tour continued down the East Coast— including six nights at New York’s Eugene O’Neill Theater—then headed into the Midwest before climaxing in California in early November with two shows at San Francisco’s Fox Warfield Theater and three at the Wiltern in LA. It was from the West Coast dates that Big Time was drawn, the hope being that all kinks would have been ironed out of the show by that point. “We did it in only two nights of concerts,” Waits told Francis Thumm. “Six cameras the first and two the next.” Subtitled “Un Operachi Romantico”8*—as Frank’s Wild Years had been—Big Time consisted of straight live footage interspersed with more staged sequences and narrative links starring Waits as the usher dreaming of stardom. “A musicotheatrical experience played in dream-time,” in the words of the blurb for the video release, the disjointed film desperately wanted to be Robert Wilson meets Robert Frank. Some of the uptempo material translated well enough, with Waits doing what by now was a well-honed hands-on-hips Mick Jagger impersonation. “16 Shells” and “Hang On St. Christopher” rocked, “Telephone Call from Istanbul” was an exultant jump blues, and “Rain Dogs” climaxed with a hilarious cod-Hebrew dance by Waits. But the more diffuse numbers— “Shore Leave,” “9th and Hennepin”—were uninvolving and the non-musical links stilted.

At times recalling the clunky artiness of Neil Young’s Rust Never Sleeps, at others resembling nothing more than a bad eighties promo video, Big Time failed to snare the experience of Waits live. “It’s difficult to retain what happened at that moment and preserve it,” Waits acknowledged. “You don’t want to kill the beast while you’re trying to capture it.” As he said to Franny Thumm, “Even when it’s great you think, ‘It’s great, but shouldn’t we have been there?’”

From LA, Waits and his motley entourage flew to Europe for three weeks of dates in the UK, Scandinavia, France, and Germany. Deliriously received shows in Dublin, London, Stockholm, Paris, and Berlin confirmed that Waits was better known across the Atlantic for Swordfishtrombones than for Small Change. Again the sets were made up almost exclusively of songs from the Island albums, though a smattering of occasional pre-Frank numbers (including “Red Shoes,” “Burma Shave,” “Blue Valentines,” and “I Beg Your Pardon”) appeased the diehards. (On the final date, at Berlin’s Freie Volksbuehne, Waits played “Muriel,” “Ruby’s Arms,” “Step Right Up,” “$29.00,” “Christmas Card,” “I Can’t Wait to Get off Work,” “On the Nickel,” and “Tom Traubert’s Blues.”)

Asked about his fan base when the tour was over, Waits replied that “the kind of thing I’m working on now, I would hope in some cases—I don’t want this to sound pretentious—but it may earn me a bit of youth …”

Waits had been so much older then. He was younger than that now.

1* Waits is a master of the descriptive X-meets-Y simile. On Late Night with David Letterman in February 1986 he told his host that Frank’s Wild Years was “kind of a cross between The Love Machine and the New Testament.” To Rolling Stones Merle Ginsberg he described it as “a little bit The Lady and the Tramp, a little bit The Pawnbroker.”

2* Supplying many of those textures was a keyboard known as the Optical Organ, or “Optigan” for short. Made between 1968 and 1972 and marketed by Penney’s stores, the Optigan featured a library of pre-recorded sounds, Waits’ favourites being Polynesian Village—“complete with birds and waterfall”— and Romantic Strings. Also featured on Frank’s Wild Years was the Mellotron, a keyboard produced by Streetly Electronics from the early 1960s and a favourite of such English bands as the Moody Blues and King Crimson.

3* Tepper, who initially agreed to talk to me about Waits, withdrew the offer after months of my chasing him. When asked why, he replied cryptically that he “knew more about the situation now.”

4* Waits went so far as to approach a guitarist at said lounge, a South Side blues institution. “The guy was probably in his late fifties,” remembers Ralph Carney. “He was kind of shabbily dressed with a CAT hat, and he seemed to have an attitude from the git-go. Eventually Tom came out and thanked him and gave him a check for a couple of hundred bucks. The guy looked at it scornfully and said something like, ‘Ah thought you was a rock star!’”

5* In a 1987 interview with Music & Sound Output, Waits claimed that with the exception of “maybe Monk and Mingus, Bud Powell, Miles,” most jazz conjured up “nylon socks and swimming pools and little hurricane lanterns and, you know, clean bathrooms and new suits.”

6* Waits would almost certainly have seen Two-Lane Blacktop (1970), in which Warren Oates (GTO) raced James Taylor (The Driver) and Dennis Wilson (The Mechanic) across America in a sunflower-coloured Pontiac while growling lines like “That’ll give you a set of emotions that’ll stay with you!” GTO was an American out of time, a counterpoint to the longhair cool of Taylor and Wilson. According to producer L. Dean Jones, Oates once saw Waits on TV and blurted the words, “That guy stole my act!”

7* “He’d just moved house and was a bit irascible,” Sean O’Hagan recalls of this interview. “Did the whole thing in character, which was entertaining but not altogether revealing. I felt like he could have done that schtick in his sleep, but I was a fan and in awe. He gave Lawrence Watson two minutes to take pictures: ‘You got two minutes, bud.’ It was unfair given that Lawrence had journeyed from London via New York with a bunch of cameras and lights.”

8* The term “operachi” was coined by Kathleen as a hybrid of opera and mariachi. “We were just looking for a word that had something to do with what this is all about,” Waits said. “I don’t want this music to intimidate people, make them think they have to take a course or something to be able to enjoy it.”