“I’m the albino catfish, you know, in the lake for a long

time. I’m gettin’ bigger, and I ain’t been caught.”

(Tom Waits, radio interview with Vicki Kerrigan, The Deep

End [Radio National/Australia], 5 October 2004)

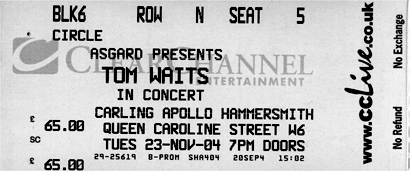

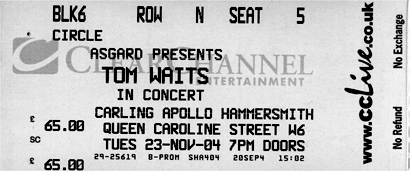

So many desperate and hopeless people are loitering outside the Hammersmith Apollo this Tuesday night—23 November 2004—that one feels vaguely ashamed to be in possession of a ticket for Tom Waits’ first London concert in seventeen years. Heartless it seems of him to stay away so long—he’d last played London at the very same venue, when it was still hallowed shrine the Hammersmith Odeon—and then limit his appearances to a single date. But such are the whims of this great American entertainer.

Any thoughts of the disappointed outside drop away once Waits takes the stage with Marc Ribot, Larry Taylor, Brain, and his son Casey (who plays congas on the first two songs). Throwing contorted shapes to the crabbed groove of “Hoist that Rag,” Waits—part pigeon-toed Lee Evans, part Max Schreck with maracas—is a sight for jaded eyes.

No sleep till Hammersmith, November 2004.

Barking orders or just barking mad? Live at the Apollo, Volume One. (Jill Furmanovksy)

Thunderous with anti-Rumsfeld rage, “Hoist that Rag” is the perfect lapel-grabbing opener. If the set is inevitably heavy on songs from the last five years and (very) light on old staples, the newer material is twistedly thrilling. If only for the reuniting of Waits and Ribot—a James Burton from Planet David Lynch— this 2004 tour has been a triumph. “All right, I know, seventeen years,” Waits grunts. “But ya look good …” He doesn’t look bad himself, and he sounds more bone-quakingly bestial than ever. Even the oddly ordinary “Make It Rain” is redeemed by the passionate despair Waits injects into its lyric.

The first real high point of the evening comes paradoxically with the undersold “Sins of the Father.” Surrender to the spooky sparseness and loping skank of this veiled assault on Bush and family, and it becomes hypnotic. By contrast, “Eyeball Kid” prompts a rather worn carny routine from Waits as Ribot picks out spiky notes on a fretless banjo. Waits concludes the ritual by playing an atonal flurry of bell-like notes on a keyboard. For the loungecore portion of the show, Waits revives the rabid Sinatra of “Straight to the Top,” drunkenly serenading a Vegas moon as Ribot supplies sleazy jazz fills. “God’s Away on Business” is pure cabaret noir.

Where “Hoist that Rag” was angry and “Sins of the Father” just politically weary, “Day after Tomorrow” is Waits at his most empathically humanist. This callow epistle from Iraq is strummed in straight singer-songwriter mode—“I still don’t know how I’m supposed to feel”—and sounds chillingly tender.

An upright piano is symbolically wheeled on for the encores. Here at last is the Waits we all secretly want: slurred, mawkish, broken. “Invitation to the Blues” is the only concession to the seventies all night, but it’s followed by “Johnsburg, Illinois” and the two great Mule Variations odes to home: the front-parlour gospel of “Come On up to the House,” the country-soul “House where Nobody Lives.”

And then, suddenly, Tom’s gone. Real gone.

Waits had sold out the Hammersmith Apollo in twenty-nine minutes, with 150,000 people attempting to buy tickets in the space of an hour. With Real Gone cracking the Billboard Top 30 in America and making the Top 10 in several European charts, he’d kicked off a short tour in Vancouver on 15 October before flying to Europe in mid-November. He was no fonder of touring than he’d ever been. “It doesn’t take much to tick me off,” he said. “I’m like an old hooker, you know.”

Backed by Larry Taylor, Marc Ribot, and Brain—with the nightly cameo from Casey—Waits played sellout shows in Antwerp, Berlin, Amsterdam, and finally London. The shows were greeted deliriously, with umpteen musical luminaries and assorted celebs—Thom Yorke, Johnny Depp, Jerry Hall, Tim Burton, Fatboy Slim—pulling strings to get into the Hammersmith show.

Waits was now universally acknowledged as an elder statesman of “alternative” rock, a godfather-hero to the likes of Yorke and P. J. Harvey. Fans and admirers the world over paid tribute to Waits in such annual gatherings and symposia as Poughkeepsie’s “Waitstock,” Denmark’s “Straydogs Party,” and the “Waiting for Waits” festival in Mallorca. Cabaret performers based entire shows on his repertoire—Robert Berdahl’s Warm Beer, Cold Women, Stewart D’Arrietta’s Belly of a Drunken Piano—while countless artists covered his songs. Norah Jones’ version of “Long Way Home”—a song Waits and Brennan had written and recorded for Arliss Howard’s 2002 film Big Bad Love—had swelled their coffers as Rod Stewart had once done.

On other fronts, too, it was business as usual. There was a lawsuit against ad agency McCann Erickson, who’d employed yet another “Waits-alike” singer to record a version of Brahms’ “Wiegenlied” in a Scandinavian ad for Opel’s new Zafira people-mover. Another suit launched in 2005—brought by Herb Cohen against the Warner Music Group and alleging that Waits had been shortchanged on the sale of digital downloads—must have been a source of bittersweet irony for Cohen’s former client.

There were movie roles that Waits either turned down or was unable to commit to. Robert Altman had wanted him and Lyle Lovett to play singing-cowboy duo Dusty and Lefty in A Prairie Home Companion. Rumours circulated that he would appear with Brad Pitt in The Assassination of Jesse James. But his feelings about acting hadn’t markedly changed since 1999’s Mystery Men. “I used to have it right there as a clause in my acting contracts: ‘Let Waits be Waits,’” he explained. “If they comply with my conditions, I do okay. You might say I’m limited as an actor, and right now I’m not interested in doing any more of it. I don’t want to be away from home that much.” The excitement Waits had experienced as a movie actor in the late 1980s and early 90s had all but worn off.

In the event, Waits plumped for appearances in three very different films. In Tony Scott’s hyper-stylized Domino, about the bounty-hunter daughter of actor Laurence Harvey, Waits was “The Wanderer,” a gun-toting Seventh-Day Adventist with a bandaged hand who passed through the desert in an old convertible as “Jesus Gonna Be Here” played on the soundtrack. “They won me in a poker game,” Waits said of the small role, which had him brandishing a pocket Bible at Keira Knightley and companions and identifying her as “the angel of fire.” As he drove them to Las Vegas we again heard him wailing on the soundtrack.

In Goran Dukic’s Wristcutters: A Love Story, an indie film about the afterlife of suicides, Waits was Ralph Kneller, an “undercover angel” discovered asleep on a deserted highway by the trio of Zia (Patrick Fugit), Mikal (Shannyn Sossamon), and Eugene (Shea Whigham). “I, uh, dozed off,” Kneller says upon rising. “I think I slept on my ear wrong. Do I look asymmetrical to you at all?”

In Roberto Benigni’s La Tigre e La Neve (The Tiger and the Snow)—partly set in invaded Iraq—Waits flew to Italy to appear in the film’s opening dream scene, performing “You Can Never Hold Back Spring” as Benigni showed up for his wedding in his underwear. “With acting,” he said, “I usually get people who want to put me in for a short time. Or they have a really odd part that only has two pages of dialogue, if that. The trouble is that it’s really difficult to do a small part in a film, because you have to get up to speed—there are fewer scenes to show the full dimensions of your character, but you still need to accomplish the same thing that someone else has an hour and a half to do …”1*

The movie cameos were distractions from the real job in hand: an ambitious three-album anthology of “antiques and curios” from the Waits archives, to which he and Kathleen had given the name Orphans. The idea dated back at least two years, intended originally for a collection of songs Waits had written for movies. But there were competing claims from an album of Howlin’ Wolf covers [Waits Sings Wolf] and one he referred to as Hell Brakes Luce.

By late 2005, Orphans was becoming a reality—a legitimate version of the five-CD bootleg series Tales from the Underground, which had brought together a motley assortment of outtakes, miscellanea, and guest appearances, along with performances for Hal Willner (“Heigh Ho,” “What Keeps Mankind Alive”) and movie soundtracks (“Sea of Love,” “Walk Away,” “Little Drop of Poison”). Waits described Orphans as “songs that fell behind the stove while making dinner,” though they included nothing before the mid-1980s. “I’m starting to get more archival as I get older,” he said. “It’s like, ‘Oh, we better hang on to this, honey. We’ll need this in our old age.’”

Waits had never been much of a hoarder, and once again he found himself having to acquire DATs of his own work from a dodgy bootlegger. “A plumber! In Russia!” he exclaimed incredulously. “I’m talking to him on the phone in the middle of the night, negotiating a price for my own shit.” In addition to such relics as “Poor Little Lamb” and “Take Care of All My Children,” Waits wanted to include newer songs he’d recorded with Marc Ribot, Brain, and Larry Taylor. These, he explained, were tracks that might have wound up on Mule Variations or Real Gone. “After we did Real Gone we just carried on and wrote a whole bunch of new songs,” he said. “You say, you’d better keep going.”

The sheer heterogeneity of the material made it difficult to organize. While he saw “no reason you can’t do a Sinatra song, then talk about insects, all that stuff on the same record,” sequencing upwards of sixty tracks presented problems. In the end it was Brennan who hit on a solution, proposing they divide the songs broadly into rougher, harder-hitting “Brawlers,” softer and more sentimental “Bawlers,” and “Bastards” that fit neither of those categories. It was the old “grim reapers”/“grand weepers” dialectic, with a new class of song to cover oddities and collaborations. “Orphans are rough and tender tunes,” Waits declared in August 2006 as Anti geared up for the release. “Rumbas about mermaids, shuffles about train wrecks, tarantellas about insects, madrigals about drowning. Scared, mean, orphan songs of rapture and melancholy. Songs of dubious origin rescued from cruel fate and now left wanting only to be cared for.”

Playing a major part in that care was engineer Karl Derfler, in Waits’ words a “battlefield medic” who “did a Lazarus on a number of the songs and recorded all the new material” at Bay View studios in the San Francisco suburb of Richmond. At times the partitioning of the fifty-four tracks eventually selected was as arbitrary as it was expedient. Some of the brawlers bawled and a few of the bastards did both. But then what would one expect in a musical orphanage run by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan?

Among the sixteen official “Brawlers” were the Mule Variations outtakes (“2:19,”“Fish in the Jailhouse,”“Buzz Fledderjohn,” “Puttin’ on the Dog”), a fuzzy cover of the Ramones’ “Return of Jackie and Judy” that somehow picked up a Grammy nomination, and a swampy, droning version of Leadbelly’s “Ain’t Goin’ Down to the Well” that Waits had recorded for a documentary about protest songs. There was another Stones homage in the grinding bullhorn boogie of “LowDown,” and a rare example of Waits attempting rockabilly—a music he’d never especially cared for—in the herky-jerky “Lie to Me.” There was a bellyful of hobo wanderlust in “Bottom of the World.”

The version of Phil Phillips’ 1959 New Orleans classic “Sea of Love” was leaden and unconvincing. “Lucinda” and “All the Time,” pained hollers of men driven mad by women, came straight out of Real Gone’s “Clang Boom Steam” school. By contrast, “Walk Away” was a bluesy song of redemption, a dry run for “Get Behind the Mule” that came from the soundtrack of Tim Robbins’ Dead Man Walking (1995). There was a touch of blackface in Waits’ treatment of the traditional “Lord, I’ve Been Changed,” originally featured as “I Know I’ve Been Changed” on John Hammond’s Wicked Grin. “Rains on Me” was Waits’ version of the song he’d co-written on Chuck E. Weiss’ Extremely Cool, complete with the same namechecks for Messrs. Body, Marchese, and Lista.

The track that really jumped out on “Brawlers” was “The Road to Peace,” an unprecedented outburst that made Real Gone’s “protest” songs look almost evasive. Inspired by a story that appeared in the New York Times in June 2003, it was a despairing seven-minute broadside about the relentless and never-ending conflict in the Middle East. “[The] article [was] about a young Palestinian suicide bomber who got on a bus in Jerusalem disguised as an Orthodox Jew,” Waits said. “The story seemed to humanize what was going on in a significant way.” Backed by Casey on drums and Ribot on glistening vibrato guitar, Waits told the old story of futile eye-for-an-eye revenge, trying hard not to toe the left-liberal line even as he demanded to know why America was arming Israel.

“This song ain’t about taking sides,” Waits maintained. “It’s an indictment of both sides.” He acknowledged the futility of what he called “throwing peanuts at a gorilla” but was unrepentant of his need to write the song, which “fell right out of the paper and onto the tape recorder.” Long gone was the Waits who, in 1984, had said, “You wouldn’t ask Ronald Reagan about Charlie Parker, would you?” Nonetheless, it was strange to hear a man who’d once sung about eggs and sausage now singing about Hamas and Ariel Sharon.

Many of the “Bawlers” on Orphans were close in feel to the ballads on Alice, with upright piano, banjo, and woodwinds dominant in the sound. “Bend Down the Branches,” from the 1998 animated film Bunny, was a tender song of resignation to ageing. “You Can Never Hold Back Spring,” the song Waits and Brennan wrote for Roberto Benigni, was a sweet statement of the hope that comes with winter’s passing. “Shiny Things” was from Woyzeck, sung by Karl the Fool, who saw crows as dazzled by glittering objects whereas the only shiny thing he wanted was “to be king there in your eyes …”

Written for Ed Harris’ 2000 biopic of Jackson Pollock, “World Keeps Turning” was reminiscent of “Take It with Me,” though its lyric was more ambiguous. The sweetly old-fashioned “Tell It to Me” was a country-folk waltz, a song of tender jealousy with Waits accompanying his own almost bel canto vocal on acoustic guitar, joined halfway through by Bobby Black’s divine pedal steel. “The Fall of Troy” was another song from Dead Man Walking, the story of two homicidal teenagers in New Orleans that recalled Mule Variations’ “Pony” and “Georgia Lee.” “Jayne’s Blue Wish” was a serene fireside ballad written for the Debra Winger vehicle Big Bad Love (2002). Another song for Big Bad Love, “Long Way Home,” was a proclamation of love and fidelity in the face of fate’s challenges, with a walking-bass arrangement redolent of Johnny Cash’s “I Walk the Line.” “When we heard the demos, there were highway sounds on the track,” the film’s director Arliss Howard recalled of the song. “Then I remembered Kathleen saying that Tom would work in a moving car with a tape recorder. And a tuba.”

A couple of the “Bawlers” were closer in spirit to the marching-band feel of “In the Neighborhood.” Aptly enough, “Take Care of All My Children” was the oldest orphan of all, dating from Martin Bell’s 1984 documentary Streetwise. Moreover, it was Bell’s 1993 film American Heart that had pulled the glorious “Never Let Go” out of Waits and Brennan. Two more songs took us back to Gin Pan Alley. Taken from Teddy Edwards’ Mississippi Lad, “Little Man” was the saxophonist’s own moving message from a father to his son—a song that must have resonated with Waits, who sang it with all the sweet affection he felt for the jazz legend. Sung by Margret in Woyzeck, the despondent “It’s Over” added harmonica to its late-night mix of piano, tenor sax, and hissing snare shuffle.

A different despondency informed the bellowy version of Leadbelly’s “Goodnight Irene,” a song of suicidal lovesickness turned into a big folk hit by the Weavers in 1950. Waits felt a special affinity with the blues giant, who’d died a day after he himself was born. “I always felt like I connected with him somehow,” he said. “He was going out and I was coming in.” Leadbelly was also the inspiration for another “Bawler,” the acoustic guitar ballad “Fannin Street.” No matter that Waits and Brennan located the latter thoroughfare in Houston rather than Shreveport, Louisiana—the scene of the young Huddie Ledbetter’s formative debauches—the song’s haunting regret came through beautifully.

The murder ballad “Widow’s Grove” was the prettiest song on “Bawlers.” A waltz played on accordion and mandolin, the song was originally written as a duet, with the victim speaking as if from the afterworld. “Little Drop of Poison” was a playfully sinister tarantella heard first in Wim Wenders’ The End of Violence (1997) and then—more profitably—on the soundtrack to Shrek 2. “If I Have to Go” was a piano ballad from Act Two of the stage version of Frank’s Wild Years, sung by Frank on the park bench in East St. Louis as he dreamt of dancing with Willa. “Danny Says” was a second Ramones cover, the flipside to “Jackie and Judy” and a tribute to the group’s sometime manager Danny Fields. “Down There by the Train” combined two of Waits’ favourite genres— gospel songs and train songs. Originally written for John Hammond but never recorded by him, it had subsequently found a home on the first of Johnny Cash’s American Recordings albums after Waits re-recorded his original demo and sent it to Cash’s producer Rick Rubin. Everyone deserved mercy in the eyes of eternity, the song said—even Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth and psycho sniper Charlie Whitman in his Texas tower. “I was like, ‘That’s it, I’m all done now, Johnny Cash did a song … thanks very much,’” Waits said. “That was really flattering, you know.”

The last song on the “Bawlers” album made Kathleen Brennan laugh out loud. A version of “Young at Heart,” sung most famously by Frank Sinatra in 1954 (and 1963), for Waits it was a virtual manifesto about how to stay fresh and vital when every biological impulse pushed you towards creative senility. Living as she did with Waits’ middle-aged grumpiness, Brennan was unconvinced. “My wife just thinks it’s hilarious,” Waits said. “She says, ‘You sound so goddamned depressed singing it … I don’t believe that bullshit for a minute. Young at heart, my ass!’” She would have been more convinced by “What Keeps Mankind Alive,” the start of Waits’ long affair with Kurt Weill. Two decades old, Waits’ stab at Macheath’s song from The Threepenny Opera sounded as savagely cynical as the day he’d recorded it for Hal Willner’s Lost in the Stars; without this performance, no Black Rider, no Blood Money. That other great Willner track—Stay Awake’s “Heigh Ho”—had Waits repurposing the song as a malevolent industrial blues, with the seven dwarves cast as exploited workers grunting to the churning rhythm of a machine going through its motions. So much so, in fact, that Disney freaked out on hearing it, convinced Waits had in some way tampered with the lyrics and made them altogether darker than they were. (He hadn’t.) Fortunately for Willner, a threatened lawsuit was dropped.

“Bastards” was otherwise made up of cover versions, spoken-word oddities, and anomalous one-offs. Skip Spence’s “Books of Moses” was done as a Mule Variations blues, Daniel Johnston’s “King Kong” as a post-Real Gone exercise in stomping mouth-hop. The furtive, conspiratorial voice of “What’s He Building?” reappeared on “Army Ants,” a list of facts about creepy-crawlies from an Audubon Society field guide recited to pizzicato strings, and on the Ken Nordine collaboration “First Kiss,” about a woman struck by lightning. There was room for an homage to Charles Bukowski, who had died of leukaemia in 1994 and whose late poem “Nirvana” was a favourite of Waits.’ “By the time he got to the Last Night of the Earth poems [1992],” Waits said of Bukowski, “he’s really a wise man and a very thoughtful man [who] was not afraid to be vulnerable. He was turning the ball around in front of him, to let him see as many sides as he could see himself.” Waits had seen Bukowski age and mellow, had watched him process his own growing fame after the release of Barbet Schroeder’s 1987 film Barfly. He’d visited Bukowski in San Pedro to discuss playing Hank Chinaski, and had seen how Linda Lee Bukowski had saved and tamed her wild husband as Kathleen had rescued him. Years after first discovering him, he was still following in the tracks of this iconoclastic father figure. “He let you go with him on his journey,” Waits said. “[It] was really great for me to have somebody you looked up to take you down the path with him.”

“Bastards” also included a nod to Waits’ first true literary hero: not one but two versions of a semi-autobiographical song Jack Kerouac had written and recorded in 1949. “On the Road” was Waits in Beefheart mode, backed by Brain, Les Claypool, and Ralph Carney at Prairie Sun in 1997. The summer of that year found him redoing the song very differently as a piano ballad, “Home I’ll Never Be,” at a Hal Willner-produced tribute to Allen Ginsberg at UCLA’s Wadsworth Theater in Westwood. “I guess Jack was at a party somewhere and snuck off into a closet and started singing into a reel-to-reel tape deck,” Waits explained. “Like, ‘I left New York in 1949, drove across the country …’ I wound up turning it into a song.” Kerouac’s namecheck for El Cajon, a suburb of San Diego, perhaps brought the lyric close to home for Waits. 1949 was also the year of Waits’ birth, “so there were places where I connected with that.”

Among the other relics and curios on “Bastards” was “Poor Little Lamb,” a sad and fragile song of hobo vulnerability co-written for Ironweed with its screenwriter William Kennedy and very much in the John McCormack vein of “Innocent when You Dream.” The lyric could almost have been about Rudy the Kraut, with the coyote “waiting out there” to grab him. “It’s based on a poem [Kennedy] saw on the side of a bridge when he was a kid,” Waits said at the time of the film’s release. “It’s like those nursery rhymes you may understand one way when you’re a kid and another way later on …” Also making the cut were two pieces from Woyzeck, the gleefully cruel “Children’s Story” (aka “Overturned Pisspot”) and the macabre instrumental “Redrum.” The first was the tale Margret tells Woyzeck’s orphaned son after Karl the Fool sings the “Lullaby” to him, a blackly funny nightmare of disappointment. The second had Charlie Musselwhite blowing alongside Waits’ ominous Chamberlin riffs—music for a killing, no less. From The Black Rider, meanwhile, came “Altar Boy”— “What Became of Old Father Craft?” redone as a full-on “show tune,” with Waits playing the pub-singer Sinatra he’d lampooned on “I’ll Take New York.”

“Dog Door,” Waits’ guest turn on Sparklehorse’s 2001 album It’s a Wonderful Life, was blues-funk, as grindingly sexy in its way as “Filipino Box Spring Hog.” “I’d done the music already but was having difficulty with the words and melody,” recalled Mark Linkous, one of Waits’ most intriguing disciples. “It was more like a dirge than a pop song. I called Tom. I said, ‘I have this cool-sounding track but I can’t finish it. I wonder if you want to take a shot at it?’ I sent it to him. He called and said, ‘Yeah, come out here. I got something.’” Linkous flew to California and put the finishing touches to a song that was all Waits and wholly untypical of Sparklehorse. “I pay attention to what those guys are doing,” Waits said of Linkous and Daniel Johnston. “I respond to it. Something resonates in me with those guys, they’re like outsider artists.” (He would make a further guest appearance on Sparklehorse’s 2006 album Dreamt for Light Years in the Belly of a Mountain, playing piano on the song “Morning Hollow.”)

Other tracks that might conceivably have worked on either Mule Variations or Real Gone were “Bone Chain,” a harmonica-blasted cross between “Get Behind the Mule” and “Clang Boom Steam,” and the crazed “Spidey’s Wild Ride.” “I had fun doing that song,” Waits said of the latter. “Just some singing and some beat-boxing. It’s very rudimentary yet at the same time very complete.” Waits loved the fact that he could do “hip hop” like this “in the washroom, in the garage, and in the car too …”

Did Waits choose to record “Two Sisters,” an eighteenth-century Scottish madrigal about homicidal sibling rivalry, because he himself had two female siblings? Either way this was Waits the Pogues fan, singing a hoary ballad of the kind he might have heard in a County Kerry snug as a fiddler sawed in the background. Family certainly played a part in “The Pontiac,” an affectionate 1987 impression of Waits’ father-in-law as he talked through the various automobiles of his life like they were former wives or old girlfriends. The piece was recorded by Kathleen in— where else—the car.

“Bastards” concluded with a pair of hidden tracks. One was simply Waits the standup comic, introducing “Invitation to the Blues” at a 2005 MusiCares benefit honouring promoter Bill Silva and Waits freak James Hetfield by telling a long story about a type of canine snack made of one hundred per cent bull’s penis.2* The other was a shaggy-dog leg-puller about a woman asking a man to call her “mom” in a grocery store because she misses her son so much, only for the man to find himself landed with her bill as a result.

When Orphans finally appeared in November 2006, packaged as a pocket-size “book” with ninety-four pages of lyrics and photographs—including snaps of Waits with Keith Richards, John Lee Hooker, Nicolas Cage, Fred Gwynne, Larry Taylor, Roberto Benigni, and others—it was hailed as a cross between the Beatles’ Anthology series and Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes. In truth there was so much music on the three CDs that it was hard for any reviewer to get his or her head around it. To my ears, many of the abandoned children gathered on Orphans could happily have remained unadopted. For every great track (“What Keeps Mankind Alive,” “Little Man,” “Widow’s Grove,” “Take Care of All My Children”), there were at least four that seemed undeserving of retrospective discovery. As for the songs recorded in the aftermath of Real Gone (“Lucinda,” “All the Time,” “Bone Chain,” “Spidey’s Wild Ride,” et al.), they confirmed what much of Real Gone itself had intimated, which was that Waits was stuck in a kind of self-parodying primitivism.

Nor, apparently, was I entirely alone in my misgivings. Film critic Jonathan Romney had written as early as 1999 that Waits had “simply swapped miniature film noir for scratchy, abstract experimental vignettes … [his] current roughneck dementia is allowed to exist freely in its own appropriate element: the more savage his new sound is, the less surprising it seems.” Writer Ian Penman implicitly concurs. “Personally I still prefer the mid-period Waits,” he says. “Blue Valentine is my favourite, and I find something just a tad ‘off about most of his subsequent work, especially the stuff that uses the blues for its formal structure. I think there’s something of an impersonation going on here that I don’t quite buy—or believe. It doesn’t touch me, ever, the way the mid-period stuff does.” I suspect Penman speaks for many closet lovers of the pre-Island Waits.

When Real Gone came out, Harp interviewer Tom Moon noted that “for much of the last decade there’s been a set of recurring complaints about Waits—that he’s too obvious about recycling his tricks, that his chronicles of love undone and his almost-romantic odes pondering mortality have become boilerplate … [that] the spectacular, almost shamanic street dramas of Rain Dogs and Frank’s Wild Years have lost a certain animating quality in subsequent iterations.”

Moon’s perception doesn’t quite accord with my own, I have to say. I’d surmise that you could count the negative reviews of Waits’ recent albums on two hands. If anything, he’s become as much of a sacred cow on the world stage as Bob Dylan. Exactly why and how this has happened is difficult to work out, but it may have something to do with just how intimidating—as well as funny, fascinating, lovable, etc.—he is. More likely, I suspect, it’s the result of Waits’ standing in the contemporary rock hierarchy, which has everything to do with the assertion of his avant-garde credentials. Certainly Kathleen Brennan has got her wish, which was to change her hubby from jazzbo self-caricature to sui generis arthouse eccentric. Arguably, though, Waits has in the process simply dumped one establishment in order to embrace another. As David Smay writes in his excellent study of Swordfishtrombones, “[his] recent adoption as National-Public-Radio-anointed National Treasure threatens to swaddle him in cultural approval, like spinach.”

All this can in a sense be traced back to the part Robert Wilson has played in the second act of Waits’ career. In the words of Robert Christgau, Waits has “forged more alliances with the institutionalized avant-garde” than even David Byrne—or, one might add, Lou Reed, another rock star to succumb to Wilson’s beguiling, gurulike seductiveness. “A bit like Wilson, Waits has been exquisitely curated,” notes David Kamp, Vanity Fair contributor and founder of the splendid Rock Snob’s Dictionary. “He’s become an untouchable, and much of that has to do with the way Kathleen has sort of rebranded him.” Former Rolling Stone staffer Anthony DeCurtis hits the nail on the head when he observes of Waits’ recent music that “a lot of critics don’t like to admit it, but even experimentalism can become predictable— you start to expect the unexpected.”3*

Back in England, respected historian Simon Schama declared himself to be a Waits fanatic in a fine piece for the Guardian in 2006. While he mostly raved, rightly arguing that there was “something almost Shakespearean about the breadth of Tom Waits’ take on modern American life,” he also voiced doubts that I and others harboured. “Sometimes [Waits] can push his furious refusal of songster-ingratiation to the edge of self-parody,” Schama noted, “so that the primal screams, grunts, howls backed by lid-clanging and stock-banging percussion just collapse into a deep ditch of vocal rage.” That got it nicely, I thought. I, for one, did not think my life would be significantly poorer if I never heard “Lucinda” or “Spidey’s Wild Ride” (or “Clang Boom Steam” or “Baby Gonna Leave Me”) again.

The reader will see from my personal selection of his best tracks (Appendix 1) that I believe Waits made as much great music pre-Brennan/Island Records as he has made since 1982: by no design, the forty songs are split exactly down the middle, with half hailing either from his Asylum albums or from One from the Heart. Furthermore, I’m with Ian Penman and others in the contention that nothing post-OFTH “touches” or moves me as much as “Tom Traubert’s Blues,” “Kentucky Avenue,” or “Broken Bicycles.” Perhaps, as Penman himself wrote me, “I’m just a sad old boho romantic who weeps at the sumptuous strings on ‘Somewhere.’” Yet whenever I’ve forced fellow fans into a corner, they’ve invariably admitted that their favourite Waits music precedes his Brennanite conversion on the road to avant-garde dissonance.

All this would be water off a duck’s back to Waits, of course. “I’m just out here trying to build a better mousetrap,” he said. “If somebody doesn’t like what I do, I really don’t care. I’m not chained to public opinion, nor am I swayed by the waves of popular trends.” To another interviewer he claimed he didn’t follow what his audience wanted to hear: “I just strike out and look behind me and there’s a bunch of people following me: ‘Go away! Go away!’”

Compiling Orphans so energized Waits that he undertook a short summer tour of the US, playing cities he’d rarely if ever visited before. Six of the dates were in the south, the remainder in the Midwest. “I don’t know what made me go out,” Waits said after the fact. “I really wanted to find out if I like doing this.” To his amazement, he liked it a lot. Planning an itinerary that circumvented airports, he travelled from town to town in a bus with a band made up of Casey Waits, the inevitable Larry Taylor, Woyzeck/Blood Money/Alice multi-instrumentalist Bent Clausen, and—deputizing for an otherwise engaged Marc Ribot—Roomful of Blues guitarist Duke Robillard. “You see the gig and the town on the way in and the town on the way out,” Waits said, “but there’s something sort of exciting about that at the same time—the stealth. You come in and sting ’em and go.”

Starting with a chaotic evening in Atlanta on 1 August, the shows sold out almost as quickly as Waits’ London date had sold out eighteen months earlier. Tour audiences dropped into the palm of Waits’ hand from the moment he took the stage. In a more accommodating mood than anyone could have expected, he reached deep into his songbook and pulled out such pre-Island evergreens as “Tom Traubert’s Blues,” “I Wish I Was in New Orleans,” “Invitation to the Blues” (often dedicated to Kathleen), “Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis,” “Whistlin’ past the Graveyard,” and “Blue Valentines.” The lingering influence of Howlin’ Wolf was felt not only in a cover of “Who’s Been Talkin’” but in arrangements of “’Til the Money Runs Out” and “Heartattack and Vine,” the latter including a short snatch of the classic “Spoonful.” (Robillard’s blues roots may have led Waits to accent this element of his music.) The unusual number of older songs possibly explained Waits’ use of a discreet teleprompter for occasional lyrical cues.

Inspired arrangements of Island-era songs (a desperate “Falling Down,” a coruscating “Goin’ out West,” a hauntingly disoriented “Shore Leave,” and a wry “Tango ’Til They’re Sore” with Waits alone at the piano) fleshed out sets that were otherwise heavy on material from Mule Variations (a groovesomely funky “Eyeball Kid”), The Black Rider (a bereft “November”), Blood Money (“God’s Away on Business”), and, of course, Real Gone. There were also foretastes of Orphans in a revved-up “2:19” a touching “You Can Never Hold Back Spring,” and a roaringly sentimental “Bottom of the World.” Waits’ comic panache was in full flow as he sat at the piano and riffed on such staple subjects as coffee, hotels, and ill-tempered waitresses. Thirty-five years after he’d first hooted at the Troubadour, he remained a brilliantly funny man. An added bonus was having his twenty-one-year-old son in his band. “He’s been playing drums since he was eight,” said Dad. “He’s a big strong guy, taller than me. With families and music, you’re usually looking for something that can make you unique, and it can be hard to find that. But he was excellent. It was terrific playing together, as you’d imagine it would be. You learn as much from your kids as they learn from you.”

Three further months elapsed before Orphans: Brawlers, Bawlers & Bastards showed up in record stores. It retailed in the US at $49.98, and no one at Epitaph expected it to repeat the success of Real Gone or its immediate predecessors. In its first week, Orphans sold 21,000 copies in the US and made the Top 10 in several European markets. In Britain, however, even the usual rave reviews couldn’t push it any higher than No. 49 in its first week, forty places below the chart entry position of Real Gone. The promotional grind found Waits in surprisingly good spirits—less churlish, gentler on interviewers. To the surprise of some, he often arrived for his media assignations in a 4x4 Lexus. “I thought, ‘Finally he’s let go of the pose,’” says Mick Brown, who was interviewing Waits for the fifth time. “But then he very sweetly presented me with a crushed tin can he’d picked up along the road.” Brown found Waits “the most genial and personable” he’d ever seen him. Waits also seemed to let his guard down a little, talking openly about his past drug abuse and his father’s alcoholism.

Former Rolling Stone music editor Mark Kemp was another interviewer struck by Waits’ new openness. “One of the more touching parts of my interview with him came when I asked where his Frank character came from,” Kemp says. “He actually began to talk about his father before catching himself and moving on to albino moles. When you get a tiny nugget of a man’s feeling in a sea of zany metaphors, it’s more powerful than an interview filled with personal details.” Kemp found even the metaphors illuminating. “I think Waits’ bizarre digressions are actually packed with meaning,” he says. “If you’re willing to follow him and not cut him off before he gets to the end of his strange tales, there’s much to glean. Like Jesus, he talks in parables that are very in line with his music and lyrics.”

“He kept going off on these long yarn-like tales about strange instruments he’d found over the years,” says Tom Moon. “But he also spoke with totally uncorny absolute awe about the late Ray Charles. The thing is, he might like jiving with people and being ‘Tom Waits,’ but at any moment he can shift course and be totally real.”

When interviewers asked about his ongoing domestic bliss, Waits said he’d “got the three cherries … pulled the handle and all the quarters came out.” He even blathered happily about growing his own vegetables—tomatoes, corn, eggplant, squash, beans, and pumpkins—in Valley Ford. “Now when I go away it’s a different feeling,” he said of home life. “I’ve got people who care about me waiting at home for me to come back.”

On chat shows, meanwhile, Waits assumed the role of affable American eccentric—a distinctive blend of performance art and genuine shyness that achieved its aim of semi-obscuring the man behind the act. His regular appearances on David Letterman found him playing a kind of Kramer—Michael Richards’ beloved “hipster doofus”—to his host’s Seinfeld.“[My kids] said I made up a war once,” he said in an anecdote that might have come straight from that peerless anti-sitcom. “I think I was groping for the real name and, uh, I just substituted it … for rhythm, you know?”

“Junkman, crackpot, musical genius.” So ran the copy on a cover story on Waits—“the mainstream media’s most beloved non-mainstream recording artist”—in Southwest Airlines Spirit magazine in March 2007. In Michael O’Brien’s sepia photographs for the piece, a huge bullhorn and battered tape recorder were strapped to Waits’ back, a manic expression on his face: this was the character who was now becoming fixed in the popular imagination.

Waits continued to make a big deal in interviews about safeguarding his privacy in a celebrity-fixated universe. The public, he said, “want to celebrate you and then they want to kill you … And then they want to remember you—even when you’re still alive.” He was adamant that what people knew about him—or his wife and his family life—was only what he “allowed” them to know. “I’m not one of those people the tabloids chase around,” he said. “You have to put off that smell—it’s like blood in the water for a shark. And they know it, and they know that you’ve also agreed. And I’m not one of those. I make stuff up.” To Time Out he made the point that “we’re not sitting in my kitchen with the dog at your feet.”4*

For actor and novelist Steve Martin, the “concept of privacy” had crystallized one day when a nurse asked him to autograph a print of his erratic heartbeat in hospital. “[Privacy] became something to protect,” Martin wrote. “What I was doing, what I was thinking, and who I was seeing, I now kept to myself as a necessary defense against the feeling that I was becoming, like the Weinermobile, a commercial artifact.” But Martin was also honest enough to concede something that Waits never does. “Sometimes,” he wrote, “a journalist will lean in and say, ‘You’re very private.’ And I mentally respond, ‘Someone who’s private would not be doing an interview on television.’”

Waits saw celebrity culture as part of a pervasive disease of mediated reality: reality TV, the flood of literary “memoirs.” For him these were manifestations of what he called “a deficit of wonder” in the world. “Everything is explained now,” he told Tom Moon. “We live in an age when you say casually to somebody ‘What’s the story on that?’ and they can run to the computer and tell you within five seconds. That’s fine, but sometimes I’d just as soon continue wondering.” Other, younger musicians seemed to be waking up to this “deficit of wonder.” “The song is independent of my face and what I look like,” said Régine Chassagne of acclaimed Canadian band the Arcade Fire. “I know in pop music people are really used to, like, relating it to the person who made it and what they eat and what they do every day. But to me it’s just independent.”5*

No photographs please: Santa Rosa, April 2002. (Jurrien Wouterse)

Waits’ deepest conviction was that truth itself was overrated. He continued to take his lead from mentors such as Bob Dylan, who’d declared Waits to be one of his “secret heroes,” and with whom he occasionally traded tapes of obscure songs. (Waits appeared twice on Dylan’s acclaimed “Theme Time Radio Hour.”) “It was a story, for God’s sake, written by somebody who tells stories,” Waits said of Dylan’s Chronicles, Volume One. “No one really knows how much of it was true or not, and no one really should know. It doesn’t really matter.”6*

The flipside of Waits’ occasional orneriness was his humility— his willingness to get right-sized about the relationship between Self and Other. Though he was “not embarrassed” to be an entertainer, he was keen not to “overvalue” himself or what he did. “You have to be careful of the ego,” he said beautifully. “It’ll eat anything.” Waits often questioned the value of his art, wondering if plumbers didn’t ultimately make a more important contribution to society.

Age has brought Waits wisdom and a growing acceptance of life’s tragic absurdity. “Most of the big things I’ve learned in the last ten years,” he said in 2004. “Of course, I’ve been sober for twelve years.” Like any great artist, however, he has one eye fixed on the immortality of his work, acknowledging that “what you really want to do is be valid and vital and in some way, here and after you’re gone: to still remain a presence and influence and still be able to sprout and bloom and bear fruit.”

Just how “valid and vital” Waits felt when movie star Scarlett Johansson decided to record an album of his songs we do not know. Following up Holly Cole’s all-but-forgotten homage Temptation, Johansson’s Anywhere I Lay My Head featured all but unrecognizable versions of “Green Grass,” “Fannin Street,” and others, recorded in rural Louisiana with TV on the Radio’s David Sitek, Yeah Yeah Yeahs guitarist Nick Zimmer, and (on backing vocals on two tracks) one David Bowie. “It was constantly in the back of my mind,” Sitek half-joked, “that if we did something Waits hated he’d come at me with a hammer.” The album seemed to cement Waits’ status as the coolest old fart in pop culture.

Johansson and Sitek started out in more faithful lo-fi style before filtering the songs through an indie-rock sensibility that’s equal parts postpunk-gothic, 4AD dreampop, shoegazing drone, and TV on the Radio epicness. The imprint of Joy Division producer Martin Hannett was all over the album, as was the influence of Suicide ballads like “Cheree” and “Dream Baby Dream.” “Falling Down” became a fusion of TVOTR and Sigur Ros, topped off with a mini-homage to the Cocteau Twins. There was even a cheeky drum-machine rendition of Bone Machine’s “I Don’t Want to Grow Up” that sounded like a Madonna demo from 1982. Johansson’s blankly androgynous alto timbre was nothing special but it barely mattered. At moments she was a Vanity Fair Nico; at others she sounded like former Moldy Peaches chanteuse Kimya Dawson. In the end Anywhere I Lay My Head reminded one of a hundred tribute albums—not least Step Right Up—but it was a bravely eccentric selection and a captivating homage to a singular American writer.7*

Waits must have been pleased that Johansson recorded only one song—a spectrally lovely version of “I Wish I Was in New Orleans”—from his pre-Brennan period. Recognition of his wife as a collaborator and equal partner was more important than ever to him. While continuing to emphasize that she was “much more adventurous than I am,” with “a wilder mind,” he said Kathleen was “one of those people that socially is so shy you’ll never hear her.”

“She’s crucial, is she not?” says Sean O’Hagan, who interviewed Waits in 2006. “I wish she’d talk, just once. She’s the source of a lot of the Irish stuff that echoes through the later songs, not just the McCormack tracings, but old ballads, stylings, ways of singing.”

Johansson’s Waits album was evidence of the ever-growing regard in which the crusty Californian was held, and of the sheer timelessness of his appeal. “I love Tom Waits because he’s an artist who makes me not afraid to get old,” remarked Matt Bellamy, singer and guitarist with UK neo-prog-rockers Muse. “I think it’s a rare kind of thing to have that level of wisdom.” Another admirer, Mark Everett of Eels, said he hoped to “grow old gracefully like Tom Waits … he doesn’t have the Mick Jagger problem where it starts to look a little silly after a certain age.”

Nor were the plaudits confined to musicians young enough to be his offspring. “I really appreciate him and everything he does and the way he works,” avers Ry Cooder, a similarly uncompromising Californian. “He’s a fantastic poet and a very high-grade guy, believe me. He’s out there and he’s one of the last of the best.” To guitar god Steve Vai there was “a purity to what [Waits] does that is really unmatched these days.”

Though Waits would have appreciated the sentiments, he was not one to rest on his laurels. Looking into the future, he felt as much at the mercy of his audience as he’d done when he first sung on the stage of the Heritage club in 1970. “Nobody knows how long they’re going to be able to stay meaningful and continue to work,” he said in 2006. “Everybody wonders that. You’re at the mercy of your audience in a lot of ways, which is really scary.” I have no doubt whatever that if he can resist the impulse to become one of America’s sanctioned mavericks, Waits will continue to surprise and delight as he eases into his twilight years. In his sixtieth year on the planet he remains as vital and confounding as any major musician in the culture.

“Do you think it’s about creating a mystique?” friends asked when I mentioned the obstacles encountered in writing this book. Generally I said that that was too simplistic, pointing out that Waits had done hundreds if not thousands of interviews over the thirty-five years of his career. I said I thought it was more about impatience with writers stuffing him in a kind of box. He wants to remain uncontained and indefinable. “I don’t like to be pinned down,” he said in 1992. “I hate direct questions. If we just pick a topic and drift, that’s my favorite part.”

Waits would surely have agreed with Susan Sontag, in her famous 1964 essay “Against Interpretation,” that, “in a culture whose already classical dilemma is the hypertrophy of the intellect at the expense of energy and sensual capability, interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art.” He might also—like David Smay in his Swordfishtrombones study—have invoked Keats’ famous concept of “Negative Capability,” defined by the poet as “when man is capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.”

One thing is for sure. For almost all the musicians who’ve worked with Waits over the years, the experience has virtually been enough to retire on. “My stance is the same as it’s always been, which is that I’ve felt honored and blessed to have played with him,” says Stephen Hodges. “As far as artists are concerned, what motherfucking songwriter do I fucking need to play with now?!”

Hodges says he divides the world into people who know about Tom Waits and people who don’t. “People ask me who I’ve played with all the time,” he says. “Sometimes I tell them. And if they look at me with a furrowed brow when I say ‘Tom Waits,’ I say … well, actually, I don’t say anything. I mean, how the fuck do you explain Tom Waits?!”

1* There was a rather meatier role for Waits when he teamed up with Terry Gilliam again on The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus. “I am the Devil,” he announced. “I don’t know why he thought of me. I was raised in the church.” Shooting on the film, commencing in London in December 2007, was interrupted a month later by the sudden death of actor Heath Ledger.

2* Quoth Hetfield in his acceptance speech, “Who needs alcohol and drugs when you have Tom Waits?”

3* That certainly goes for Robert Wilson, who seems increasingly to operate as a super-crony and shameless infiltrator of the moneyed arts world. His Voom video portraits of movie stars such as Brad Pitt and Johnny Depp must surely have left a queasy feeling in Waits’ stomach.

4* I was amused to stumble on this blog entry, posted by a Sonoma County resident after a local musical get-together in November 2007: “After the song was over, all the audience members took turns calling out what personal facts they knew about Waits—that he drives a black Prius, that he visits his local Radio Shack a few times a week, that he lives out near Valley Ford … I love how everyone wants so badly to ‘know’ this man. I am guilty too.”

5* In an online interview with himself in May 2008, Waits reiterated that “we are buried beneath the weight of information, which is being confused with knowledge,” adding that “quantity is being confused with abundance and wealth with happiness.” I think he’s right on both counts.

6* “The minute you try to grab hold of Dylan, he’s no longer where he was,” wrote Todd Haynes, director of the 2007 anti-biopic I’m Not There. “Dylan’s life of change and constant disappearances and constant transformations makes you yearn to hold him and to nail him down. And that’s why his fan base is so obsessive, so desirous of finding the truth and the absolutes and the answers to him— things that Dylan will never provide and will only frustrate.” The question irresistibly suggests itself: will Waits ever write his own Chronicles?

7* A rather more conventional reworking of the Waits songbook—and one tilted slightly more towards his pre-Island oeuvre—was Grapefruit Moon by Asbury Park legend Southside Johnny with LaBamba’s Big Band. Along with the title track, the 2008 album included “Please Call Me, Baby,” “New Coat of Paint,” and “Shiver Me Timbers.” Waits himself guested on a lusty rendition of “Walk Away.”