5

Profile Picture, Right Here, Right Now

JEREMY SARACHAN

My friend didn’t get it. She was criticizing my Facebook picture when I used it in a professional context outside of Facebook. “Not very serious,” her comment suggested. I looked at her photo. The image was perfectly centered. She had a vague smile on her face. When posting identifying pictures for business, do people still expect a head and shoulders shot with the subject staring straight ahead? It’s time to stop thinking that way, to stop taking photos like that.

Passport photo-wannabes just don’t hack it anymore. Not for us connected folk. After friending people in Facebook, the first thing I do is check out their profile picture. There’s a thrill in seeing a new Facebook friend who was also a real life friend twenty years earlier. It’s like going to a high school reunion, but with instant gratification and less self-doubt.

Facebook is a visual scrapbook of friends from the present, past, and even future—if you haven’t yet met in real life. The profile picture gives meaning to the text-heavy page. Despite the tools of image manipulation, photographs are viewed as a representation of the world. The bits of data (digital and factual) that make up the News Feed offer line after line of communication, musings, and quiz results about individual friends (”Which punctuation mark are you? Colon.”) But without the image, all the text in the world, from status lines to group membership to quiz results, would be information overload.

Text alone does not make the person. Images make us real. Depending on security settings, the profile picture usually can be viewed by anyone who searches for a particular name. Think of it this way: when you walk down the street, you are there. Others may not know anything about you, but they see you. As banal as it sounds, your visibility makes you real. It’s the same for Facebook. But, these images destroy the expectation of what a portrait should be. In this context, a typical passport-style shot signifies only that you exist—and who wants to be friends with someone who does nothing but exist? Facebook users demand more.

All about the Punctum

In his book Camera Lucida, French Philosopher Roland Barthes examines photography from both analytic and personal perspectives. Barthes uses the terms studium and punctum as a means to understand a photograph when first viewed. Studium refers to the description of the picture, focusing on its content and meaning. The punctum is more immediate: what strikes you about the photo at first glance, what emotional impact it makes, or what “sticks” with you. Facebook profile pictures are all about the punctum. They create a reaction in an instant. Conversely, traditional head and shoulder shots lack personality. There’s no punctum.

This focus on immediacy makes the creation of a Facebook image challenging. The ability to repeatedly update one’s image motivates a desire to outdo oneself. It also gives license to break rules. In professional photography, a trained photographer may be able to successfully reproduce what Barthes calls the “air” of the subject—the fundamental nature of that person or the “intractable, supplement of identity.” (For contemporary examples, check out magazine covers by Annie Leibowitz on Google Images.) But most individuals have neither the interest, the money, nor the time to hire a professional photographer each time they want to post a new profile picture. (And where would be the fun?) In creating self-portraits, Facebook users attempt to display their air, but only for that one moment in time. This redefinition of air becomes more instantaneous and temporary—a disorienting but reasonable requirement for the digital age.

In Camera Lucida, Barthes describes the “Winter Garden Photograph” of his mother that he feels expressed her air. He discovered the photo while still mourning her death and he acknowledges that the image’s punctum is specific to him. “For you, it would be nothing but an indifferent picture, one of the thousand manifestations of the ‘ordinary’. At most it would interest your studium: period, clothes, photogeny; but in it, for you, no wound” (p. 73). While less emotionally invested than Barthes, a viewer of a Facebook photo is likely to have the necessary familiarity with a Facebook friend that would allow him to perceive the air.

For Barthes, the importance of the air leads him to dismiss other photographic techniques such as showcasing a particular physical movement; creating a special effect, like slow-motion photography; producing a “contortion of technique” that would be created today through the use of image manipulation software; or most commonly, happening upon a “lucky find” (pp. 32-33). The last technique requires a trained eye to notice a special moment as it occurs. Many shots that achieve iconic status depend on the photographer’s tenacity and experience in knowing where to aim the camera. (For examples of such recognizable shots, google “iconic photographs.”) But ultimately, Barthes suggests that all of these techniques obscure a truly meaningful image that displays an individual’s air.

Yet Facebook users combine these approaches, while still creating photos that reveal aspects of their personality. Some of the photos may be a “lucky find,” but more typically the conscious decision inherent in Facebook photographs point to a continual attempt for a meaningful representational image. The photographer may consider the pose and physical movement, background, lighting and composition. He may also use Photoshop to alter the photograph. Facebook’s constant flow of information demands repeated changes to the profile picture. A self-defined best image becomes obsolete within a few days. The need to experiment with new approaches to recreate and redefine one’s air is a never-ending effort.

Cameras Are Everywhere: Start Clicking.

Smaller cameras and cell phones (and iPhones and Flip video cameras) allow users to create images wherever and whenever they want. These devices result in real, casual, and convenient depictions of everyday life. The lack of visual standards eliminates self-consciousness. One isn’t always pretty or dressed-up or “ready.” Photographs that previously might have been discarded are not lost. The ephemeral quality of the images—they’ll be replaced in a few days anyways—allows the formerly unseen glimpses of one’s hidden self to emerge. The natural expressions, unkempt hair, and lack of purpose create meaning through their examination of normality. If kept in a scrapbook, these same images would influence our perception of the subject: “he is a messy person.” But everyone is unkempt sometimes, and the brief existence of the profile picture matches the temporary states (sleepy, messy, angry, happy) of the subject.

Such spontaneity was impossible in the mid-nineteenth century when cameras were large and expensive. Taking a portrait required an entire family to sit absolutely still for several minutes in order to get the proper exposure and avoid blur. These pictures hardly represented reality. During the twentieth century, technological advances from the Brownie to the Polaroid made things easier and more convenient. The compactness of the newest devices eliminates the decision to be a photographer on a given day. One no longer has to make the choice to take a camera to the zoo or an uncle’s wedding; a camera always sits in one’s pocket because it’s a function of some other object. Carrying a camera has become as ubiquitous as wearing a watch used to be, before the cell phone became many people’s timekeeper of choice. Posting is equally easy. Using a Blackberry or iPhone, one can easily upload a photograph directly to the profile picture.

Barthes stated that “I am not a photographer, not even an amateur photographer: too impatient for that: I must see right away what I have produced.” He would have embraced digital technology, which allows one to see images immediately. Sites such as Flickr and Twitpic permit instant display. Additionally, the large number of Facebook users creates a potentially unlimited and immediate audience.

Users with hundreds or even thousands of friends can show off the new pictures of the baby to many more people than would ever see them sitting around a scrapbook on the living room couch. The flip side to this is that viewers are constantly inundated with images. Traditional pictures all look the same and it’s easy to ignore typical photo album-style pictures. In the information age, the overabundance of data results in massive indifference. For this reason, photo tagging is a necessary feature in Facebook. You’re notified whenever someone else tags (identifies) you. Who doesn’t want to see pictures of himself?

Social networking offers the ultimate distribution mode. Facebook offers a display more public than a non-virtual photo album ever could. In this way, images achieve a level of importance where in the past they may have been left in the bottom of the shoebox or deleted from the digital camera before they could be printed. The question of “Is this a good shot?” (whatever “good” means) becomes irrelevant. All content is acceptable. The profile picture becomes the most important because that image is repeated in the News Feed whenever an action is taken; it functions as a visual symbol of your online life.

Not Your Father’s (or Your) Yearbook Picture

Pictures in high school and college yearbooks are interesting despite their similar compositions because the image freezes the viewer at age eighteen or twenty-two, to be occasionally re-examined on the rare occasion when the yearbook is pulled off the top shelf of the bookcase in the basement. The consistent picture style is all that is required because the endless anecdotes balance the blandness. (“You think he looks smart and mature? Let me tell you what he and his friends did to the gym after the prom!”) Like a folk tale, the stories are exaggerated and amended. The static image only serves as a memory jog.

Facebook photos aren’t timeless. They aren’t meant to tell stories through the years. They create immediate moments. Status lines and Facebook images rarely function together to create a coherent meaning. Instead the Facebook user offers two perspectives to communicate who he is at

any given time. In a sense, the long-standing and meaningless exchange of:

“How are you?”

“I’m fine.”

is replaced by visual and written (even poetic) accounts of how or who someone is at different times throughout the day. You’re no longer represented throughout life by a single professional portrait or yearbook photo. Facebook demands the constant recreation of the self, and demands a high level of creativity and a break with traditional expectations. Considering Barthes’s idea of the punctum, a good Facebook profile picture creates a deep and immediate impression; even better if it’s powerful enough to express the air of the subject.

Barthes’s Photographic Categories and Facebook Portraiture

Barthes suggests that analysis can only be accomplished with photographs that don’t depict tragedy: “the traumatic photograph (fires, shipwrecks, catastrophes, violent death, all captured ‘from life as lived’) is the photograph about which there is nothing to say.”

36 Only a mundane (read: Facebook) photo offers the ambiguity necessary for substantial analysis. Barthes lists six categories for consideration:

• Pose: the subject physically presenting himself and what this says about his status, personality or attitude

• Objects: props and the background and how they influence the understanding of the subject

• Trick effects: in modern terms, what one accomplishes with Photoshop

• Photogenia: technical elements like composition and lighting

• Aestheticism: whether a photograph should be viewed as art

• Syntax: the language of photography that allows a viewer to extract meaning

The Pose: Just the Computer and Me

A common profile picture shows the user posed at a desk in front of a computer. This is an “authentic,” low-resolution webcam shot of the author taking a break from writing. Does such a picture create a meaningful and lasting impression? The image is recursive: a portrait of the person using Facebook. Such shots tend to show the subject with a slightly distorted face (if the camera is too close) above the camera lens, putting the subject in a position of power. But who’s really in control? These images tie the subject to the computer. Although the subject is seen in the absolute present, it also limits him to a life encompassed by the machine. Every other photographic style seen in Facebook is a direct response to this basic approach.

37Accepting the basic punctum of “Here I am!” created by a webcam pose, how else can the subject be placed?

The Reconsidered Pose: Hiding in Plain Sight

Some Facebook images break expectations entirely by reconsidering the expectations of a posed shot, instead using an object to distort or hide the subject. Frequently a form of media—newspapers or a screen—obscures the face. This puts emphasis on action, sometimes linking the profile picture with the status line, while declaring that the minimal expectations of any portrait (seeing a face) are neither important nor desirable. It’s all about attitude.

In a similar vein, a Facebook photo may show a specific portion of the body with personal meaning. As seen in this image, a tattoo provides a captivating statement about an individual well beyond a simple written statement of fact: ‘I have a tattoo.’

In some instances, an artistic image that depicts something other than the subject reveals a part of the subject’s personality or behavior. A coffee cup creates a more powerful statement of overwork than a vaguely tired face. A piano captures a hobby.

The punctum is created by the lack of a face or the replacement of the subject. The use of another object demands analysis.

Living Objects: I’ve got Real Friends and Places to Go

The objects included in a Facebook photo helps define the user, especially if we expand the notion of “object” to include another person. Some users choose to demonstrate their connection to the non-technological world through relationships with friends, family or romantic partners. In this way, Facebook information is validated with visual proof. I have real friends. I am in a relationship. This may create a sense of isolation for online friends as they become further removed from one’s real-life friends. It can be difficult to “only” be a Facebook buddy.

Alternatively, a subject may show himself in another place with non-technical props,

38 so as to broaden others’ expectations and disconnect from the online world: “I control Facebook. It does not control me.”

The punctum is created by the background content—the other people or place depicted in the photograph.

Trick Effects: Manipulation and Popular Culture

Individuals who use image manipulation software to somehow alter their appearance through Photoshop wish to convey their personality or feelings through artistic creation. The face becomes secondary to the method, being reinterpreted to show off the personality of the subject both through the literal change of appearance and the chosen artistic style.

Some people use or manipulate copyrighted images for their profile picture. Whether a cowboy from a 1940s movie, a character from South Park, or oneself as a Simpsons character

39 the ability to acquire and upload any image allows for connection with a character or dramatic situation and bonding with other fans of that film or television program. Copyright violations are undeniable, but being one of millions is liberating, minimizing the fear of punishment.

Facebook itself is overrun with pop culture references. Quizzes allow users to determine how well they know the trivia surrounding a show or which character they are most like. This attempt to re-identify speaks to Facebook’s purpose. Quizzes clarify one’s identity in a manner unique to social networks. If you declared what mathematical equation you were in a face-to-face conversation, you would likely be viewed as odd. But on Facebook, declaring which dead writer you are most like helps to create your identity while connecting you to other classic literature fans.

The punctum is created by connections to design history and pop culture—the subject is linked to a larger idea.

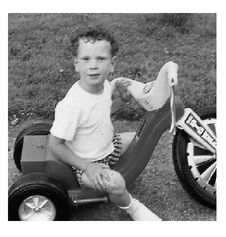

Less Tricky Effects: The Past Is Present

Rather than manipulating an image, the simple use of a scanner to digitize old photographs from years or decades earlier can lead a viewer into a moment in personal history while distancing the subject from the immediacy of Facebook. As the subject no longer looks quite like his former self, a profile picture has been created with a loophole. The image is nostalgic and “safe” in terms of not showing too much of oneself. Yet, the user also has defied others’ expectations for a profile picture and therefore rebelled against the status quo. Most importantly, this connection with the past adds depth to the visual identity of the user.

The punctum is created by past—the sense of a life B.F. (Before Facebook).

Photogenia: Movies as Motivator

The consideration of technical elements may lead to a subject appearing in silhouette which breaks with the expected rules of photographic lighting and composition—the hidden parts of the face suggest thoughtful blocking reminiscent of film. The movie-inspired photo, similar in style to the photographs of Cindy Sherman (check them out with Google Images), instantly infuses the subject with all of the characteristics suggested by the specific genre. An image depicting the pose of an action-style hero gives the subject those qualities, even momentarily, until the artifice returns a second meaning to the viewer: I’m a fan of action movies.

Aestheticism: Facebook as Art Gallery

Facebook promotes artistic expression. Considering the predominance of text, the profile picture offers the major means of visual expression. Specific visuals change, but that box of color and light remains. (Some Facebook users write poetically in their status lines, but those tend to be lost in the flow of the news feed.)

Consequently, Facebook users who possess visual creativity can extend Facebook past expectations. Images that would be aesthetically pleasing outside of a social network find their way into distribution through Facebook, creating a global gallery of artistic pieces, even encouraging users to check out past profile pictures of the most visually talented users. The subject is presented in a deliberate manner, suggesting a specific mood or theme. The shots typically utilize the entire frame to create strong lines and a clear focal point to direct the viewer towards a pensive face.

Users possessing this level of artistic expertise are likely to be creative outside of Facebook, and in this way, Facebook does what it’s supposed to: convey information about the nature and interests of the user.

The punctum is unique, as suggested by the creativity of the artist.

The Syntax of the facebook Portrait

Photographs enhance our understanding and serve to remind us of people we know. Facebook photos have no more commercial value than family photos stored in an album. One of my friends is a professional actress and she has posted her professional portfolio portrait on Facebook. This exceptional instance may lead to financial risk if her photo were to be appropriated as her image potentially could be used for advertisements and other endorsements. For the rest of us, our everydayness is only worth the value of friendship it helps to evoke and maintain.

Ultimately, profile pictures offer Facebook users the opportunity to add metaphorical personality and literal color to the page. Images add meaning to the text-based profile, and this multilayered syntax requires that a page be read with regard to all of the embedded media. Unlike sites like MySpace that are highly modifiable, Facebook’s lack of variability allows it to maintain a high level of readability and user-friendliness. However, this clarity comes at the cost of plainness and even sterility. The images—the profile pictures and other posted images running through the News Feed—bring the page to life. The stream of images combined with the text creates an interactive framework that displays aspects of identity specific to the page’s creator. Consequently, these profile pictures may arguably be the most important aspect of Facebook. Certainly, the countless and continuous acts of creation have led to new rules of composition and focus appropriate for temporary images reflective of the moment. Traditional design principles fall away with a new emphasis on realism. Centered subjects are passé and the rule of thirds difficult to create in the small Facebook status box. Design considerations are replaced by the rapid, mass consumption of images.

In his 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” German philosopher Walter Benjamin discusses the effect that the reproducibility of photography and film had on attitudes toward art, but he also points out that the “camera introduces us to unconscious optics.” In other words, we see moments in time that we would miss with our eye alone.

40 We see a thin slice of absolute reality. A turning away of the face does not necessarily represent an individual who is angry or shy. An overly dark room doesn’t necessarily reflect “bad lighting.” Art photographers have known that such rules were meant to be broken. Now thanks to affordable technology and simple and uncritical mass distribution, everyone is free to experiment with self-portraiture.

Barthes offers a commentary on his contemporaries, which simultaneously predicts the mass creation associated with social media:

I live in a society of transmitters (being one myself): each person I meet or who writes to me, sends me a book, a text, an outline, a prospectus, a protest, an invitation to a performance, an exhibition, etc. The pleasure of writing, of producing makes itself felt on all sides. Most of the time, the texts and the performances proceed where there is no demand for them; they encounter, unfortunately for them, ‘relations’ and not friends. (Roland Barthes, 1977, p. 81)

It’s all there: continuous postings on Facebook not “demanded” by anyone, sent to Facebook friends—in many cases merely “relations.” Digital technology provides new ways to produce and easier methods to distribute, but the desire to create is not new.

Facebook makes everyone a photographer. Everyone can be different. Everyone can be avant-garde. Is it quality work? (What does quality mean in this context?) Does it matter?

Try it—you can put anything in that box.

Do it. Do it.

There.

Your work is on display.

On the last night of an academic conference held in Monterey, California, I had the opportunity to wander along Fisherman’s Wharf and found myself sitting opposite one Mr. Bell, a retired art teacher, who sat at his easel in the moonlight, drawing a portrait for this tourist.

Despite our ongoing cordial conversation, my mind drifted to this chapter you are reading, which I was composing at the time. Long before the digital age, Walter Benjamin pointed out that the original emphasis on art was its uniqueness—value emerged from its singular existence. Copies were merely reproductions, forgeries, fakes. Photography and film changed this—each print or copy retains the value of the original. Images meant to exist only on the web push this concept further. No original exists of an image taken by a webcam, only infinite copies that paradoxically always and never exist. Consider the question of whether a tree makes a sound if it falls in the forest and no one’s around to hear it; now consider that a web-based image only exists when someone views the page. Otherwise, it is merely bits on a server. The importance of an “original portrait” loses all meaning when uploaded directly into Facebook.

After my session with Mr. Bell, I held carefully to a one-of-a-kind, cartoonish image of myself, precisely positioning the rolled paper in my luggage to avoid damage and wrinkling. I was greatly relieved when I got the drawing home and scanned it into my computer so that I would have a “safe” copy of the drawing. Until then, that work—that memory—was fragile (telling people I had my portrait drawn in Monterey was perhaps more important than the work itself.) The drawing was neither instantaneous (I sat for as long as those nineteenth-century families) nor everywhere.

But then I wondered. Should I bring the image into the twenty-first century? Should I post that scanned drawing to Facebook, making it my profile picture, for a time? Should I let it reproduce infinitely?

Mr. Bell told me the drawing was mine. I could use it wherever and however I wished..

And I didn’t know what to do.