“A narcissist isn’t in therapy to get better.

A narcissist is in therapy to get you to

participate in his symptoms.”

—James Masterson, M.D., one of the pioneers of object relations theory

The narcissist is a wounded individual with a disorganized personality. He may agree to therapy simply to avoid the pain of recurrent narcissistic injury. (Kernberg, 2000) Narcissists come to therapy in the first place to try and alleviate some situation that has triggered intolerable pain. Typically, they do not go to therapy because they want to become better people or to better interact with a loving significant other.

Since the root of narcissistic behavior is shame, a narcissist will trigger the shame of anyone who endeavors to get close to them, including a therapist. For this reason, counselors must be aware of and deal with their own shame when conducting therapy with a narcissist. Also, a narcissist has a need to idealize the therapist and then systematically bring him or her down. This roller-coaster ride can be quite daunting, and it’s important to remember that this must occur at some point in therapy: the need to project the “bad parent” on to the therapist is part of the healing process. The following case exemplifies this experience.

Don is a well-dressed businessman who has been in a gay relationship for many years. He’s quite closeted and neither his family nor his work colleagues are aware of his relationship. His friendships are nonexistent. Occasionally, Don cruises the bars at night and admits that he has had unprotected sex with younger men. He can’t comprehend why his partner finally became fed up with this behavior: “If he’s boring me, why shouldn’t I be able to otherwise entertain myself in the evenings!” His lover wants to break up with him and Don feels both angry and distressed about this situation.

When he first walked into my office, Don seemed rather shy and quite reluctant to describe his lifestyle. His story slowly started to unfold during the first session and I was aware of the amount of pain he was carrying. The first clue that Don had narcissistic traits occurred when, while speaking to him, I quickly glanced over at the clock to see how much time we had left. Don glared at me and snapped, “You know, Rokelle, if you’re so uninterested in what I have to say, I know there are dozens of therapists who’d love to have me as a client!” His acute awareness of any small shift in attention sent off alarm bells in my head. Despite this, we set up several appointments for which he was always punctual. But he was always insulted when I’d ask him to sit in the waiting room until the previous client exited.

At one session he came in and began talking about a handsome young man who had picked him up the evening before. I was amazed that although he was desperate to salvage his current relationship, he would still continue this same destructive behavior. As I listened to his description of this man, I commented on what a deep sense of self-hatred he must have to need and feel so gratified by these fleeting contacts: “Don, are you saying that for a brief time you forget how freakish and unlovable you feel?”

Don looked incredibly sad and said, “That’s right. For just a few moments, I feel that I am important and desirable.”

“I bet that when my eyes aren’t meeting your gaze during our sessions,” I continued, “you feel that same sense of unimportance.”

Acknowledging Don’s shame and keen sensitivity to shifts in my attention formed a cornerstone of our therapeutic relationship.

Gradually Don spoke more about his feelings of unacceptability. He showed his vulnerability when he spoke about his parents, their self-involved behavior, and how he felt both like a showpiece and insignificant. At the same time, his swelling grandiosity began to emerge in his description of work relationships. He described his colleagues as “small items” and unworthy of his abilities. He felt superior to his bosses, thought they were envious of his talent, and believed that he could run the company better than any of them.

Through the course of our sessions, Don began to exhibit the narcissistic overvaluation/devaluation cycle: for a time, he believed that I was the best therapist in town, that he was so lucky to have found me, and that he was going to recommend me to his well-to-do associates. He wanted to make sure that he was my special client and became incensed when I would politely refuse to meet him for dinner. However, as he improved in acknowledging his shame and ceasing his sexual acting out, his attitude toward me moved between gratitude to hurt and annoyance. In other words, I noted a growing competitiveness alternating with real affection. His idealization of me began to diminish as he noted my mistakes in interpretations, my mispronunciations, and at times, my lack of style.

One session, he sat in his chair staring at my hands. I became self-conscious and asked him if there was something wrong. He sneered at me and said, “Rokelle, how can you walk around like that in public?”

I was aghast. I didn’t have a clue what he was referring to and asked what he meant.

“Can’t you spend the money to have your nails done once in a while? I honestly would be embarrassed to be seen with you.”

I looked at my nails and the paint was, indeed, chipping off. I tried to continue the session sitting on my hands but was so ashamed that I had difficulty concentrating. During the lunch break I ran to the manicurist while calling a colleague of mine for consultation.

In short, Don was working through his defectiveness and his issues with his critical, cold mother through transference. I was up on that pedestal for a period of time, but gradually he had a need to see me as similarly flawed. I asked him the next session why the condition of my fingernails was so important to him. He explained how all he felt was disgust and anger, as if my unkempt nails were a statement of my lack of respect for him. In other words, Don had a need to idealize as well as humiliate me. Gradually, as he was willing to tolerate my imperfections, he became more tolerant of his own.

Transference refers to redirection of a client’s feelings for a significant person to a therapist. In Don’s case, his emotions toward his mother were unconsciously directed toward me. This is exactly the dynamic that is so injurious to lovers, partners, children, friends, and coworkers. In therapy, the key to success is the ability of the clinician to endure this transference without abandoning the process or overreacting. Needless to say, this is a tall order.

When Don focused on my appearance, I had everything I could do to control myself from saying what I really wanted to say. I was so caught off guard and felt such embarrassment that I wasn’t able to refocus the issue back to Don until the next session. Yet, this is the key to change. The narcissist is susceptible to treatment only when his defenses are down. Attacks on the therapist are indications that a narcissist is feeling threatened and needs to devalue the therapist; the underside of this response is raw vulnerability.

As therapists, we must endeavor to remain emotionally neutral. If we become upset or distant, we are probably caught in anger counter transference issues of our own. In addition, directly challenging the narcissist is usually unproductive. As a colleague of mine once remarked, “Challenging a narcissist on his or her behavior is like trying to interact with a bucket of tar. The more you try to get at it, the more you become stuck in it.”

The idea in calling attention to a narcissist’s behavior is to focus on identifying the vulnerability and gently linking it back to his defenses. If you are successful, a narcissist will be able to take in what you say rather than going into narcissistic posturing. Many psychologists believe that it is working in this way with transference that allows the client to grow and to transform. (Jung, 1969)

I must emphasize here that it isn’t the job of any child, partner, or coworker to work with this redirection of emotions. However, I hope this discussion may provide some perspective to those who live or work in close proximity to a narcissist by showing that these reactions have absolutely nothing to do with them.

We know that narcissists hold the delusion that they’re at the center of the universe. The longing for admiration and attention coupled with this delusion challenges any of us. When a therapist sets boundaries with a narcissist, the reaction isn’t going to be pleasant. Any boundary that has been set will trigger a narcissistic wound; yet these limits are precisely what will allow this person to sit with and process their shame. The following example underscores both the need for boundaries and a narcissist’s hypersensitivity to lack of attention.

Mrs. Harris grew up in a family where she had to perform to get attention and was not loved or appreciated for who she was, only for what she could give her parents. She craves attention and when she doesn’t get it, the shame becomes intolerable and it quickly turns into attacks on others. She came to me because she was discharged from a law firm due to the way she was treating her clients. She was an excellent attorney, but the firm was losing business because of her outbursts. This incident left her feeling depressed, ashamed, and furious. Mrs. Harris had just lost a primary source of narcissistic supply and was experiencing the devastating pain of her narcissistic wound. The following incident occurred just when Mrs. Harris and I had reached a level in our work together where she was beginning to disclose her vulnerability:

Mrs. Harris encountered me at an opera one evening. It was during the intermission and I was standing and talking to a group of friends when she came up to me and wanted to engage both my friends and me in conversation. Her husband was with her, but she’d abandoned him in the crowd and rushed over to me. I excused myself from the group and greeted her, and said that I hoped she was enjoying the wonderful performance. After a couple of minutes, I gently excused myself and went back to chat with my friends. In other words, I acknowledged her, but didn’t spend the entire intermission engaging with her. I knew there’d be hell to pay, but putting a boundary between my private life and my client was necessary.

In her next session, Mrs. Harris ranted and raged at me for daring to ignore her by spending my time with others. She was insulted that I didn’t introduce her to my friends and asked if I was embarrassed to do so. I explained that to protect her confidentiality, I was bound not to disclose her identity. This wasn’t satisfactory to her and she even asked me if I didn’t introduce her because of what she was wearing that evening! At one point, she glared at me and said, “Your problem is that you think you’re too good for me, don’t you.”

Because I hadn’t attended solely to her and because others in my life had commanded my attention, she was incensed. In her mind, I was supposed to be available to her no matter what the circumstances. As we explored her response, it emerged that she had felt invisible, insignificant to me, and of no importance—and these were the exact emotions that she had experienced as a child. She left the opera feeling mortified and worthless. In other words, she left with her own feelings of shame, a feeling that she desperately tried to eliminate. In truth, it was her desperate need for constant validation of her importance to me that filled her with humiliation. Rage was a reflexive way of ridding herself of this overwhelming emotion.

Since Mrs. Harris came to me with the presenting problem of her uncontrollable rage, it may have been technically correct to focus on this issue. She could have attended anger management courses for the rest of her life; but that final step of working back to underlying shame is the key for narcissists and is, unfortunately, too often overlooked in treatment.

EMPATHY AND COMPASSION

ARE NOT ENOUGH

“Many people naively believe that they can

cure the narcissist by flooding him with love, acceptance,

compassion, and empathy. This is not so. The only

time a transformative healing process occurs is when the

narcissist experiences a severe narcissistic injury.”

—Sam Vaknin, 2007

For therapists, it’s difficult to work with narcissists and remain compassionate. They are demanding, self-righteous, and often insulting.

However, we know that narcissists have been badly wounded in their lives and we need to maintain our compassion for them. It’s quite evident that the extent of their rage and bullying is the extent of their trauma. However, a therapist can empathize with a wounded, grandiose narcissist for a few decades, and that won’t shift their behavior.

An effective style for working with a narcissist is one of firmness combined with gentleness; indeed, the model of what a healthy parent should have been. Many of our clients who are diagnosed in the Cluster B category will show up feeling out of control. For many of these people, starting as the nurturing, empathic, gentle therapist in the beginning doesn’t make them feel safer; it leaves them feeling more out of control. When working with a narcissist, a therapist must provide nurture as well as structure; narcissists also need the therapist to be especially clear about the direction of their work.

Providing external structure creates the safety necessary to do deep and vulnerable work with a narcissist. And even though this structure will be resisted with behavior ranging from narcissistic fury to endless rationalizations, therapists must hold these boundaries. What do I mean by external structure? Starting and ending the sessions on time, charging for missed appointments, saying no to meetings, dinners, or other social engagements outside the confines of therapy, and resisting the urge to adjust one’s boundaries because of one’s compassion or the narcissist’s intimidation.

By the way, since intimidation is part of the defensive strategy for narcissists, I wouldn’t recommend working with this type of client unless one has supervision. The phrase “It takes a village” comes to mind here. Most of us need support to maintain our equilibrium with challenging clients. If a therapist feels physically intimated by any patient, then practicing self-care is imperative. It’s not helpful to our clients or to ourselves to continue to be engaged in a therapeutic process when we feel unsafe.

When a narcissist is wounded, he is at greatest risk of acting out against others. Witnessing this reaction and working through the anger of the underlying shame is of great therapeutic benefit. However, when the narcissist’s defenses have let him down and he believes his world is collapsing he is at greatest risk of becoming rageful and even violent, particularly if he has a need to seek revenge. Because of the intensity of the narcissist’s emotions, the counselor needs to deal very carefully with this anger and avoid a power struggle. During these episodes, the narcissist will sense this and will most likely use this anger to intimidate. Therefore, it’s crucial that anyone working with a narcissist receives supervision, learns to self-soothe, and is willing to refer out if necessary.

UNCOVERING THE PAIN

As shown in the story about Don, narcissists may modify their behavior when they learn to reveal why an incident felt painful and are willing to track back to earlier wounds of rejection, betrayal, and shame. Those insights will need to be articulated by the therapist in a descriptive and nonjudgmental way that says, “Of course, you desire nurturance,” or “You must have felt very betrayed.” Then, the narcissist can begin to soften the rigidity of his or her defensive stance.

Therapists can actually use narcissistic features of their patients to engage and assess them. To avoid angering the patient, it’s important to work with, rather than belittle, the narcissistic ego. A therapist can, for example, address a patient’s heightened self-importance and desire for control by saying such things as, “Because you are obviously such an intelligent and sensitive person, I’m sure that, working together, we can get you past your current difficulties.”

In a crisis situation, the therapist can assess the patient’s defenses and put them to therapeutic use. Take the example of a somatic narcissistic patient who complained about his wife’s reaction to his anger.

“Rokelle, my wife called the police on me simply for getting angry at her and throwing a couple of things at the wall.”

“What did you throw?”

“I threw two garbage bins filled with trash only to make a point. She refused to empty them and said it was my job.”

“Had you been drinking?”

“Perhaps I had a few beers after work.”

“Let’s come up with a plan so this doesn’t happen to you. I would imagine that was really a humiliating experience. If you don’t want her to call the police, then it will be in your best interest to stop throwing things at her. Next time this happens, you’ll be taken to jail. And by the way, drinking not only makes you angrier but also ruins your physique. There is no amount of exercise that can metabolize large quantities of beer. I know you take pride in how wonderful you look and I’d hate to see you ruin your physique.”

Obviously, there may be an addiction problem here that will need to be addressed. But the aforementioned dialogue can be a prelude to opening this topic of discussion.

In short, narcissistic personality traits can be used to provide motivation for therapy. The narcissist may be encouraged to change negative behaviors as a reward for recovery: a better appearance, improved career prospects, or improvements in their romantic and sexual life.

USE GROUP THERAPY

It’s difficult to do ongoing one-to-one therapy with a narcissist. Group therapy can be helpful for these patients, but the therapist should, tactfully but firmly, place limits on narcissist’s speaking time so that they cannot control the discussion or focus all the attention on themselves. Explaining that members of the group need to share the time, therapists may want to make a contract with patients with narcissistic personality disorder before each session to encourage prosocial behaviors. Some of these behaviors include:

• Limiting speaking time

• Not interrupting other speakers

• Respecting the feelings of others

• Responding to other group members

• Listening objectively to responses and feedback from others (NIH, 2006)

COUPLES WITH NARCISSISTIC WOUNDS:

DINOSAUR BATTLES AND CAT FIGHTS

Narcissistic couples are often chronically angry at each other. These couples often wait too long to go to therapy or may have tried therapy with someone who did not provide enough structure for them. Therefore, they enter therapy frustrated, hopeless, and often bitter.

It’s not uncommon to find in couples one arrogant narcissist and one shy narcissist who has lost his or her voice and uses passive-aggressive tactics to express anger. The tragedy of these couples is that after a very short time they withhold love, warmth, and attention from each other. Ironically, what they complain about most is what they cannot tolerate getting.

For instance, picture a session with a narcissistic wife who has a passive, withholding husband. Each session her complaint is the same: “Rokelle, he doesn’t share emotions. He’s as cold as ice and he really doesn’t know how to connect. I will not continue to be in a relationship with someone who is emotionally impaired.” Then, when her husband finally shows vulnerability, her reaction is dismissive, petty, and sarcastic: “There you go whining like a baby. Why don’t you grow up? I want a man, not a child.”

Instead of continuing to meet with this type of couple together, individual sessions would be more useful. The benefit in meeting with each partner separately is twofold: First, it gives the therapist a chance to explore each patient’s vulnerability in regard to his or her partner. Second, even though narcissists lack the ability for empathy or compassion, individual sessions are important for setting up a boundary against brutal sarcasm and reactive anger.

Some of the significant qualities and behaviors you’ll see in narcissistic couples include:

1. Rapid escalation of hostility.

2. Intense need for intimacy without the skills to support this need.

3. Lack of self-responsibility.

4. Avoidance and intolerance of vulnerability.

5. Inability or avoidance of seeing the impact they have on each other.

6. Repetitive triggering of trauma in each other without the skills to achieve resolution.

7. Lack of compassion or a feigned performance of empathy.

8. Ongoing search for narcissistic supply as an answer to their problems. (Bader, 2004)

ENGAGING A NARCISSISTIC SPOUSE IN THERAPY

A colleague of mine worked with a recovering alcoholic who was married to a man with strong narcissistic traits. This woman was rather new in recovery and wanted to work on her painful relationship issues. She indicated that for her, there would be no sobriety unless there was more peace in her personal life. Granted, it’s difficult to work on a relationship unless two willing participants are involved, but her husband refused to join her. He made it perfectly clear that although he would pay for his wife to go, it was his wife’s problem and for him, therapy would be a waste of his time. In short what he was communicating was, “If you fix my sick wife, we’ll be fine.”

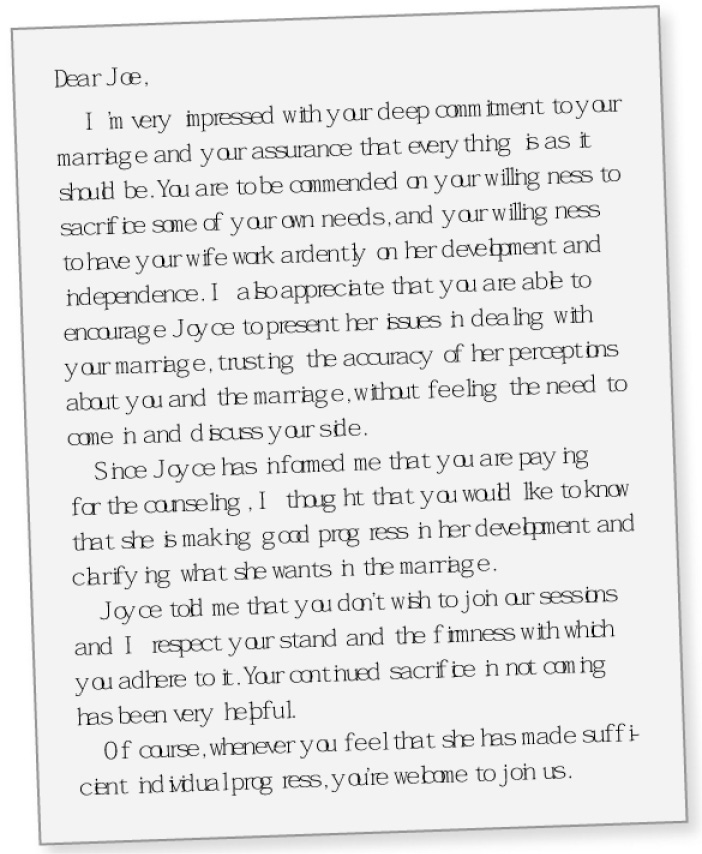

Through the course of therapy it became evident that this woman could only go so far in working on her relational issues without the presence of her husband. Her situation was so abusive at home that she was close to relapsing. My colleague was puzzled as to how to bring the husband in without forming a posse. With some research, she found a solution using an approach called paradoxical intervention. Basically, the purpose of this technique is to stop a problem behavior by prescribing the problem behavior. The following is the letter she sent to this resistant, narcissistic husband:

As you can imagine, Joe found the letter very unsettling. It dawned on him that he couldn’t monitor what his wife was saying about him, and he felt threatened by the fact that she really might be getting healthier. The very next day he called the therapist and explained that as long as his wife had made progress, his participation wasn’t going to be a problem for him. The following week, the therapist found Joe and his wife in the waiting room. Joe was doting over his wife, holding her hand, and smiling sweetly—behavior that he used only in the presence of others.

Clearly, relationship problems are never one-sided. It would be a mistake to blame all the issues in a relationship on one partner. Even though a relationship with a narcissist is painful, the spouse of a narcissist must face certain questions:

• What factors allow him or her to remain in an abusive relationship?

• What keeps him or her from voicing their truth and setting boundaries?

• What is the family history that taught him or her to become resigned to suffering?

• Where did he or she learn that they had the power to change or fix another human being?

• What is he or she willing to do in the future and what kind of support do they need?

Threatened with the loss of a primary supply, a narcissist may choose to modify his behavior. (The operative word here is “choose.”) Is this done out of love, remorse, or compassion? Probably none of the above. Still, it is possible that a couple can coexist with boundaries in place and more realistic expectations established.

I must add a caveat: if couples therapy concentrates primarily on helping, for example, Joe and his wife communicate more effectively, nothing much has been accomplished. Even teaching good conflict resolution skills won’t be enough to help salvage this relationship. For a narcissist, finding the vulnerability under the rage and grandiosity is key, as well as learning to self-soothe without causing destruction. For a spouse, the work involves learning how to self-validate, self-soothe, and maintain boundaries; acknowledging that if he or she doesn’t set boundaries they will be consumed; and delving into the reasons for the spouse’s high tolerance for abuse.

MEDICATION

Narcissists will generally balk at the use of medication. Since they believe they are above the rest of humanity, resorting to medication is an admission that something is wrong. Many are fearful of becoming one of the masses and losing their uniqueness with medication. Since a narcissist must dramatize his or her life to feel special, one might hear the following rationalization: “I am not like anyone else in the world and medication affects me differently.” Contrast that to narcissists who claim to have discovered new and revolutionary ways of using medication: “I’m experimenting with this medication to benefit humanity.” Suffice it to say that if they are prescribed medication, many narcissists will likely refuse it, or use it in ways that are not productive.

Narcissistic personality disorder cannot be effectively treated with medication alone. The underlying disorder is managed by long-term psychodynamic or cognitive-behavioral therapies. However, the symptoms associated with narcissism, such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), pathological lying, paranoia, and angry outbursts are sometimes treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) medications such as fluoxetine/Prozac. It’s possible, however, that if SSRIs are not used as prescribed, adverse effects may lead to agitation that exacerbates the rage attacks that are typical of a narcissist. Not enough is known about the biochemistry of NPD but there is research that indicates success in using heterocyclics, MAOs, and mood stabilizers, such as lithium, that don’t have the extent of unfavorable side effects that SSRIs do. (Lowen, 2004; Vaknin, 2007)

Constructing a non-defensive self through therapy or treatment is not short-term work for the narcissistic client. There are many obstacles to overcome and still the prognosis for significant change is minimal. It’s of utmost importance that those in relationship with a narcissist delve into their own issues, practice self-care and boundaries, and learn how to deal with the emotional abuse that exists in relationship with a narcissist. There is a danger for those in relationship with narcissists to avoid working on their own issues. Many times through the years I’ve heard spouses of narcissists express that the source of their pain is centered on the behavior of their husband or wife: “So what does that have to do with me?” There is a belief that if their partner goes to therapy or treatment, romance will return and life will be happy again. Unfortunately this is a pipe dream and far from the truth.