Chapter Three

The Stations

The local nerve centres of the railways were the stations. They served many more functions than today’s generation could imagine, and the man (usually) in charge was the railway station agent. Therefore, one of the building’s main roles was to house the agent and his family, and this was almost always in an upstairs or rear apartment. The agent had to issue passenger tickets, as well as organize (and often solicit) freight shipments. To keep the trains moving, he issued train orders by “hooping” them up to the engineer on a long curved or forked stick known as a hoop. He also fixed the signal in front of the station to indicate to the engineer if he needed to slow down, stop, or continue through. Preparing the mail sack was still another duty for the agent, as many trains contained a mail sorting car right on board.

Agents also enjoyed a more aesthetic role — maintaining the station garden. Some of the earliest and largest gardens were those laid out beside the stations in Regina, Medicine Hat, Moose Jaw, and Calgary. The CPR’s first nursery was established at Wolesley, Saskatchewan, under the direction of Gustaf Bosson Krook, a Swedish-born horticulturist who held the position for twenty years. During the First World War, the gardens switched from flowers to vegetables, and after the Second World War, to parking lots. Between the wars, greenhouses in Winnipeg, Calgary, and Moose Jaw were providing 125 different varieties of flowers and shrubs.

While a community’s first station was more likely than not to be either a converted boxcar or passenger coach, Canada’s railways quickly got down to building more substantial stations. How big depended upon the business emanating or projected from that location. Once the designs became more elaborate, the railway station became the signature of the rail line that was building it, which each line having distinctive patterns.

The CPR was the first railway to cross the Prairies. In its haste to reach the Pacific coast, which was the goal behind the company’s creation, it very quickly erected stations. Its first president, William Cornelius Van Horne, sent a common station plan to contractors along the line: a very simple full two-storey building with gable ends, usually with a single storey freight wing. These served for twenty years or so until the CPR, to attract more business, devised a greater variety of more aesthetically pleasing station designs, primarily for small-town way stations.

Many of these stations owe their appearance to Ralph Benjamin Pratt, the CPR’s main architect from 1898 to 1901, at which point he was hired away by the Canadian Northern Railway. He came up with two of the CPR’s more interesting styles. One such design, displaying an attractive mansard-style roof, appeared largely in Manitoba, although several were built along the CPR’s Calgary and Edmonton line and the Qu’Appelle, Long Lake and Saskatchewan lines. Rosthern, Saskatchewan; Didsbury, Alberta; and La Riviere, Manitoba, are surviving examples of the twenty such structures that were built on the prairies. Another of his classic styles consisted of a high pyramid above a second storey and featured pagoda-style flourishes on the roof tip and gables. Of twenty-two such CPR stations, sixteen were built in Manitoba.

This station in Theodore, Saskatchewan, was designed by R.B. Pratt and is one of the CPR’s more interesting designs, with its pagoda-like features.

With the next style the CPR introduced, in 1905, Pratt’s absence was noticeable. The first of these designs, which the CPR designated as “Standard # 5” and “Standard #10” (the only difference being in the size), appeared in 128 communities in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Consisting of a simple two-storey structure, the design’s only embellishment was a hip gable above a pair of second-storey windows.

In 1909 the CPR came up with the Western Line Stations (WLS), which were built exclusively across the Prairies. This style, known as “A-2 WLS,” was similar to its predecessor stations, the main difference being that the front gable on the second storey was peaked rather than hipped, and nearly all were built in Alberta and Saskatchewan (172 of 197 were found in these provinces). This style also appeared later, along the CPR’s new Toronto to Sudbury main line in Ontario.

This era of simpler stations was followed in the period of 1920–30, when the CPR introduced its A-3 WLS, which is considered to one of that line’s more interesting stations. Again the stations were two storeys in height, and the designers decided to bring the front gable down the full width of the second-storey facade. Sixty-one were built between 1920 and 1930, most along the new Lanigan to Melfort line and as replacement stations in Manitoba. A half-dozen survive, largely as museums or private homes.

Ogema’s “new” station displays one of the CPR’s most common and more simple styles introduced following the departure of R.B. Pratt.

But as the 1920s wound down, and the auto age diminished the prominence of the country station, the CPR’s final station design marked a return to simplicity. Erected between 1924 and 1931 in sixty-two locations, mostly on new branch lines, it was a two-storey structure with the second level appearing as a large dormer. A wide, sweeping roofline added a pleasing flourish to the building. Several of these now serve as museums.

Many stations were designed for divisional points, where more staff needed to be accommodated. These structures were surprisingly small, but in such locations, staff accommodation could usually be found in the community. A particularly pleasing style was allocated to more than a dozen divisional points throughout Alberta and Saskatchewan. This design consisted of only a single storey, and a large flared gable dominated the roof, both front and back, while a wide wrap-around eave displayed a similarly flared roof. The front entrance was by means of a porte-cochère, again with a flared roof.

With this station style at Oxbow, Saskatchewan, the CPR began to reintroduce more aesthetically pleasing buildings.

Finally, the grandest designs were reserved for the largest towns and cities. The popular Richardsonian Romanesque style influenced the CPR’s then-architect Edwin Colonna in places like Calgary, Swift Current, Regina (preceding the current building), and Portage la Prairie. The stations in Lethbridge, Strathcona, Medicine Hat, Red Deer, and Saskatoon all followed a common Château-style influence, while those grand urban terminals in Winnipeg, Brandon, and Regina were all custom-designed along neo-classical lines, using arches and pillars to mark the entrances. Altogether the CPR erected nearly 1,200 stations — more than half in Saskatchewan — roughly one third were portables.

The Canadian Northern Railway, which was building as many branch lines as it could as inexpensively as possible, came up with a mere three different styles. Created by CNo architect Ralph Benjamin Pratt — who, as mentioned, was lured from the CPR in 1901 — these designs included the common wayside station, which was a storey-and-a-half with a steep pyramid roof and a prominent dormer to represent the location of the agent’s quarters. The effect was pronounced, as these high roofs could be easily seen for a great distance, especially on the flat, treeless landscape — a design element which was intentional. These structures were labeled as “class 3” stations. Between 1901 and 1924, 293 CNo 3rd class stations were built (a few were also constructed by the CNR using the former plans), with 145 in Saskatchewan, sixty-nine in Alberta, and sixty-two in Manitoba.

The station in Outlook, Saskatchewan, now a museum, shows the divisional style of station used by the CPR across the prairies.

Less important locations received single storey structures, where the agent might enjoy only a small apartment at the rear. Known as “class 4” stations, hundreds still stand, though most were relocated to become homes or museums.

Divisional stations were likewise identical. While sporting the iconic pyramid roof, they were also given wings on each end of the main building, and these, too, would include dormer windows on the second level. Many of these survive, including several on site.

Between 1901 and 1916, the CNo constructed sixteen 2nd-class divisional stations in the Prairies, with five in Alberta and four in both Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

A small handful of grander custom-designed stations appeared in places like Dauphin, Manitoba (still standing); Saskatoon (removed, but a replica was later built); and Edmonton. Regina’s station became a union station with the CPR, and the Winnipeg station joined the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway in building an exemplary union station there.

The station at Cudworth, Saskatchewan, was a style introduced by the CNR after it took over the CNo’s branch lines.

The third main line, the Grand Trunk Pacific, similarly kept its variety of station styles to a minimum. For the most part, it applied only two patterns to its way stations, and even those were nearly identical. Those country stations displayed attractive little designs, which featured wide overhangs and a bellcast roof, differing only as to whether they employed an octagonal or square dormer above an octagonal or square operator’s bay window. Of those that survive, most have been relocated to become homes or museums. Divisional stations offered more variety, ranging from full two-storey, half-timbered structures, such as that still standing in Melville to those with more prominent dormers. This line created 206 small town and rural stations.

The successor to the GTP and the CNo, namely the Canadian National Railway, while not needing to add many new stations, kept them simple — usually a full two storeys with little flair or embellishment. Towns with examples still standing on site include, in Saskatchewan, Glaslyn, Frenchman’s Butte, and Cudworth. After the CNR entered the picture, it added a further 103 stations in the towns and villages of the Prairies.[6]

The Big Valley station is the kind that the CNo used at their prairie divisional points. Along with the grain elevator, it presents a heritage railway landscape.

Saving the Stations

By the mid 1950s, railways were switching from coal-fired steam locomotives to those powered by diesel, and this dramatically altered the railway landscape of the Prairies. As diesels could travel farther and faster without refueling, every other divisional point shut down. Roundhouses, coal docks, and water towers no longer served a purpose, and centralized traffic control eliminated the need for station operators to pass along train orders to the engineers. In addition, the CN and CP introduced centralized service operations to process freight orders and shipping, and many station agents became redundant.

Although less glamorous than steam engines, diesels such as these on display in Medicine Hat hold considerable aesthetic appeal.

Then, with the end of the mail contracts and a sharp decline in passenger travel — thanks to the ever-present automobile — more stations went quiet. The decade that followed witnessed the elimination of 80 percent of the railway stations across the Prairies and indeed throughout the country. Of the nearly two thousand stations built across the three prairie provinces, only 720 remained as of the mid-90s, the last time a station census took place.[7] More than 90 percent of these had been dragged off to become barns, private homes, or restaurants. Only a small handful remained on site.

Farsighted municipalities saw the risk of losing their heritage and gobbled up the old buildings, primarily for museums but also for libraries and seniors drop-in centres. Regrettably, the railway companies usually forced the purchaser to remove the building from the station grounds, and all too many were ignored and demolished. The mass extermination these cherished heritage buildings, especially in the Prairies’ towns and villages, which would not have existed at all were it not for train stations, led to an outcry across the country. In 1988 the federal government passed into law the Heritage Railway Station Protection Act. Once designated as a protected structure under the act, a station could not be demolished or even significantly altered. In less than ten years, the environment minister, responsible for the legislation, granted more than 300 stations this designation.

In Saskatchewan, designated stations included the following:

• Biggar

• Broadview

• Humboldt

• Melville

• Two in Moose Jaw

• North Battleford

• Regina

• Two in Saskatoon

• Swift Current

• Wynyard

Manitoba also had several designated stations:

• Brandon

• Churchill

• Cranberry Portage

• Dauphin

• Emerson

• Gillam

• McCreary

• Minnedosa

• Neepawa

• Two in Portage La Prairie

• Rivers

• Roblin

• St. James

• The Pas

• Virden

• Two in Winnipeg

The following stations in Alberta were also designated:

• Banff

• Empress

• Hanna

• Jasper

• Lake Louise

• Medicine Hat

• Red Deer

• Strathcona

In all, thirty-eight stations have received federal protection across the Prairies. Many others have been designated under provincial statutes or municipal bylaws. Twenty seven stations are listed on Saskatchewan’s Register of Heritage Places.

Designations didn’t always save them, as many were simply left neglected. Some met their fate at the hands of arsonists, while others simply crumbled into rubble.

Survivors: The Urban Terminals

Many of the major urban terminals that dominated the Prairies’ urban landscapes are still around. Few original structures, however, have survived the need to enlarge or upgrade to meet the ever changing needs of the railways. Sadly, grand terminals that stood in places like Calgary and Edmonton are now gone, while the only such structure to still provide rail passenger service is the Union Station in Winnipeg. Others have earned new uses, as in Winnipeg’s CPR terminal, which is now an aboriginal centre; Regina’s Union Station, now a casino; Lightbridge’s CPR station, a health centre; and Saskatoon’s CPR station, now a tavern and travel office.

Lethbridge, Alberta

In 1895 the CPR extended a line south from of its main line tracks to a small village called Coalbanks in order to tap into the supply of coal in the area. In 1898 the line was further extended to the larger coal seams in the Crowsnest Pass. In 1905 the town of Coalbanks changed its name to Lethbridge. It then encouraged the CPR to relocate its divisional point from Fort Macleod by granting the railway a twenty-year exemption from taxes on 48.6 hectares of land near the downtown. The CPR agreed and built the current station, along with freight sheds and a roundhouse.

Its design is similar to several other such stations across the prairies — such as those in Strathcona, Red Deer, and Saskatoon — and it sports a row of dormers along the former trackside and an iconic octagonal tower on the street side. In 1980 the CPR relocated its yards to Kipp, and the station sat empty. With the redevelopment of downtown Lethbridge, and the relocation of the tracks farther north, the CPR station became a regional health centre and stands today as a designated provincial heritage resource. Despite the absence of tracks, the railway heritage is further enhanced by the placing of CPR steam locomotive 3651 beside what would have been the station’s platform and the placing of a caboose at the opposite end. Lethbridge is also the site of one of Canada’s most stunning railway trestles.

Red Deer, Alberta, CPR Station

In 1890s, the tracks of the Calgary and Edmonton finally arrived at the south bank of the Red Deer Creek. Although it had meant moving the village’s original buildings to trackside, the town of Red Deer began to boom. In 1904 the Canadian Pacific Railway took over the C&E and established Red Deer as a divisional point halfway between Calgary and Edmonton. In 1910 the CP replaced the simpler C&E station with one of their grander designs: built of red brick, the storey-and-a-half structure was topped by a large turret with several hipped dormer windows along the roofline. Divisional tracks sprawled before it, while a large garden with a central foundation was laid out on the streetside entrance. But in 1985, with a major redevelopment occurring in downtown Red Deer, the CPR relocated its tracks and the station became an office building.

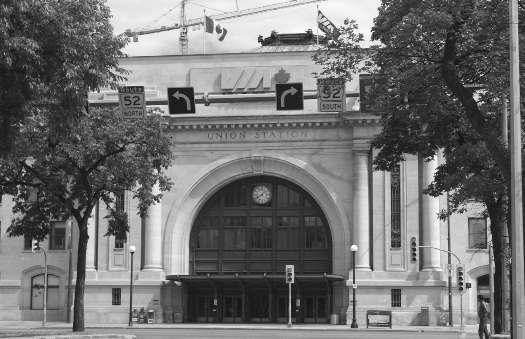

Winnipeg’s Union Station

This gateway city to the Canadian Prairies was geographically the convergence of Canada’s three major east–west lines. While the CPR was content to enjoy its own station near the city’s north end, the CNo and the GTP, along with the GTP’s partner the National Transcontinental Railway (NTR), decided to construct a union station to serve both lines. It was, however, the CNo that actually built the structure, with the GTP and NTR as tenants. Accordingly, the CNo engaged the well-known New York firm of Warren and Wetmore to design a grand Beaux-Arts station.

As with many urban stations, the entrance was to be the building’s grandest feature. Just as the ancient Greeks and Romans used archways and pillars to mark the grand entrance to their cities, so too did the railway companies for their stations. In the case of the Winnipeg station, the grand arch extends the full three storeys and is topped by a dome. The waiting room, too, reaches the full height of the building and is finished in marble, with arched skylights containing the provincial coats of arms and gold leaf around the walls. While regular passengers could enjoy the amenities of the main hall, arriving immigrants were segregated into their own facilities on the lower level.

The station still serves VIA Rail passengers travelling on the train named Canadian and the Churchill trains. A museum on tracks 1 and 2 contains what is perhaps the most historic piece of railway equipment on the Prairies, the Countess of Dufferin, the first steam locomotive to enter service on the Prairies. A walkway leads from the waiting room beneath the tracks to the newly redeveloped Forks complex, where the Manitoba Children’s museum is housed in the Northern Pacific and Manitoba Railway engine house and car shop.

Winnipeg’s Union station was a collaboration between the CNo and the GTP, and is one of the few functioning stations left on the prairies.

Winnipeg CPR Station

The CPR’s then-main architects, Edward and W.S. Maxwell, chose to incorporate into the Winnipeg station the Beaux-Arts style school of architecture, which was then in vogue. This is a style that also appears in the CPR’s Vancouver’s station and in Montreal’s Windsor Station. The new station in Winnipeg was opened in 1914 and replaced an earlier brick station. Likewise constructed of brick with stone work around the windows and setting off the corners, the grand four-storey entrance is marked by two sets of twin pillars embedded in a concrete base. The top of the entrance is richly decorated, and much of the original fixtures still survive in the vast waiting room. Designated both federally and provincially as a heritage structure, the building now houses an aboriginal centre.

Saskatoon CPR

Another of the CPR’s grand prairie-chateau stations is that in Saskatoon. Being that city’s third rail line, following those of the CNo and GTP, it did not occupy a prominent location in the urban context. It was, however, accompanied by a roundhouse and rail yards, and twenty trains per day passed through the station. The large yellow brick building is two storeys high and displays a fifteen-metre trackside polygonal turret, which incorporates the operator’s bay window at track level and extends above the roofline. In 1960 the station was closed, although the CPR continued to use the building as an administrative centre. Finally, the station was vacated in 1972 and efforts for its preservation began. It was designated as a heritage structure under the Heritage Railway Station Protection Act in 1989, one of the first in the country to be so protected, and now houses a variety of businesses along with a grill and restaurant.

Saskatoon CNR

The CNo’s first station in Saskatoon was built at the west end of the city’s main street, 2nd Street. Later, the CNR would add the Bessborough Hotel at the opposite end of the street. The CNo station sported the line’s signature pyramid roof with gabled extensions to each side. The CNR replaced it in the 1930s with a neo-classical building with a flat roof, and it had pillars to mark its two-storey entrance. Later, in 1964, with the CNR looking to the expanding suburbs for clients, where it located today’s modern station, the CNR demolished its downtown station.

Saskatoon’s new CNR station reflects a more modern heritage. One of the few such post-war stations constructed in Canada, it was built at a time when the CNR was recognizing the role of the automobile. Its location on the western outskirts of the city was intended to appeal to the car-oriented suburban population. It is unusual to consider a building constructed as recently as 1964 to be a heritage resource, but that is nonetheless the case with this station. It was built in what is known as the International style. With its high ceiling and flat roof, and with its ample window area, it is very much the modern station. No longer needed by the CN, its sole remaining function is that of the station stop for VIA Rail’s Canadian. It was designated as a protected station under the Heritage Railway Station Protection Act in 1996.

Strathcona (Edmonton CPR)

When the Calgary and Edmonton Railway was completed to the south bank of the North Saskatchewan River in 1898, it went no farther, due to the costs of building a major bridge over the river. The first station was a small wooden standard plan CPR station, a replica of which is now a museum in the community of Strathcona. In 1912 the CPR replaced the simple station with one of its grand designs. Because of its status as a terminus, Strathcona grew into a significant-sized town. With a trademark polygonal turret on the building’s trackside, the two-storey structure housed waiting rooms, freight offices, and accommodations for the railway staff. The station’s walls are brick, while its corners and turrets are clad in Tyndall stone. It resembles other CPR stations in Red Deer, Saskatoon, and Lethbridge. Following the station’s closure in 1980, it was converted to a tavern and restaurant.

Edmonton CNR

The CNR, with R.B. Pratt its architect, built another of its stunning pyramid-roof urban stations. The centre portion was three storeys with a gable dormer front and back and small decorative turrets on the corners. The two wings, of two storeys each, featured three prominent dormers, three windows wide, set into the sweeping bellcast roof. Meanwhile, a wide overhand wrapped around the entire structure. Although the GTP built its own line well to the north of that of the CNo, it began to use the CNo station as well. In 1928 the CNR built a new International-style structure nearby to replace it, although the older station remained until 1952, when it was demolished. The newer building stood at two storeys, with a flat roof and a pair of pillars to guard the entrance. This building, like its predecessor, stood at the north end of 101st Street, looking south toward the Hotel MacDonald. In the 1960s, that structure, too, made way for a CN office and operations building of typical 60s design. It was nicknamed the “CN Tower,” and the passenger waiting room was at the ground level.

But even that building no longer houses railway operations. In 2008 the CN removed its operations to the massive Walker railway yards, while VIA Rail, too, vacated the premises for a location adjacent to the City Centre Airport. Its new facility is a bright and spacious structure with a wide awning over the entrance that sports the trademark blue-and-yellow VIA sign. This attractive modernistic building also features Wi-Fi. It is located on 121st Street, just south of the Yellowhead Highway.

Medicine Hat (CPR)

The 1906 CPR station in Medicine Hat, Alberta, copied the style found in Strathcona, Red Deer, and the other areas. The building featured the polygonal tower at trackside, with two prominent dormers on the second floor on each side of the tower. By 1911, the yards had become so busy, and the city had grown so quickly, that the station was in effect doubled in length by an identical addition to the east and a large addition between the two.

Today, the yards remain among the railway’s busiest, and yet an another addition was added on the street side to accommodate staff and operations. Designated as a heritage structure both federally and provincially, the station retains a number of interior features as well as a portion of its original garden, one of the first such station gardens in western Canada.

Calgary

Calgary, like Edmonton, had seen its stations come and go. It is hard to believe that its first station was in fact just a converted box car. That was quickly replaced with the more standard “Van Horne” station. It, too, was quickly outdated, and a pair of identical stone structures replaced it. These were wide and single storey. As Calgary continued to grow, it was soon obvious that the city needed something even larger, especially after the opening of the Pallisser Hotel in 1914. And so the CPR dismantled the twin stone stations — reconstructing them in High River and Claresholm — and built a large new neo-classical facility east of the hotel. Its central section with a flat roof stood three storeys high and featured extensive wings, which rose two storeys. In the end, even that facility gave way to the building boom that swept downtown Calgary, and eventually the station was relegated to the hotel itself. No passenger trains pass through Calgary anymore. Tourists riding the elegant Royal Canadian Pacific tour train now board through a glass-covered building.

Neither the Canadian Northern nor the Grand Trunk Pacific Railways built their own stations in Calgary. The GTP moved into a former RCMP barracks, which has long vanished beneath Calgary’s redevelopment. The CNo building, on the other hand, is still very much around. Built in 1905 as St. Mary’s parish hall, the building was the centre of a French-Canadian section of Calgary known as Rouleauville. The area never realized its cultural potential, and in 1911 the church sold the building to the CNo. Although the railway would have preferred to build a new station when it came time to expand, its precarious wartime finances forced it to instead add a brick extension to the rear of the building.

The hall itself is a three-storey sandstone structure with a mansard roof on three sides and a Boomtown-style facade. The CNR closed the station in 1971 and it remained vacant for a number of years. Despite being gutted by a fire, the building was restored and still stands today, but as a ballet school. Tracks still lead across a small bridge behind the building.

Saskatoon reflects one of the CPR’s grand urban styles found predominantly on the prairies.

Regina’s Union Station

It may have, on occasion, been a gamble to ride the rails in the early days on the prairies, but today that has literally become the case in Regina, with its sequence of different stations. When the CPR arrived in 1886, the first station it erected was the same standard plan, the wooden two-storey style, that it erected everywhere. It replaced that one with an Edward Colonna–designed low brick-and-stone building with a prominent tower above it. Finally, in 1911, in conjunction with the Canadian Northern Railway, which was busily adding branch lines, the CPR built the city’s third station. In 1912 the three storey limestone building opened to traffic. The arched entrance led to a full three-storey waiting room replete with chandeliers. The station incorporated bas relief pilasters, lacy iron canopies, and carved stonework. Single-storey wings extended to each side, and the current front portion was added in 1931 as an extension to the waiting room.

To make way for this new Union Station, the earlier structure, minus tower, was moved to Broadview, Saskatchewan, where it yet stands, although in some disrepair. With the end of VIA Rail’s passenger service in 1990, thanks to cutbacks in service by the government of Brian Mulroney, the station closed. Protected by the federal HRSPA, the station survived and in 1996 opened its doors as the Casino Regina. While slot machines now clatter away on the ground level, in the basement there remains a jail cell formerly used by the CN police (it now houses historic photos of Regina).

In the eastern wing, the names of the restaurants reflect the building’s rail heritage: the Last Spike, the Rail Car, and the CPR lounge. The Rail Car restaurant does indeed occupy a CN passenger coach, beside which stands a CPR steam locomotive. The grand foyer still looms three storeys high, and its historic chandeliers yet dangle.

The Canadian Northern’s Divisional Stations

Athabasca, Alberta

Here, the CNo’s standard class-2 (plan 100-39) divisional station remains in the same spot as when it was built in 1912 and Athabasca was at that time the end of steel. It closed in 1973 and became a seniors drop-in centre. In 2010 the Athabasca Heritage society leased the building from the town and is currently working to restore it to a 1912 appearance.

Big Valley, Alberta

The town of Big Valley presents one the Prairies’ more complete railway heritage landscapes. Built in 1912 as a class-2 divisional station by the CNo, the station reflects plan 100-39 (the same used for Athabasca’s station), another of Pratt’s designs. With the CNo’s typical pyramid roof in the centre, the main portion is flanked by a pair of extensions, each with a small gable. As a divisional point, the station grounds also featured a roundhouse, the ruins of which still survive, and an elevator and passenger coach round out the landscape. The station, in original condition, is a station stop for the Stettler steam excursion trains, and it houses a museum inside.

Canora, Saskatchewan

The CNo station in Canora is unique in that, while it is a museum, it is still used by train passengers travelling on VIA Rail’s popular Churchill train. It was built on the CNo’s main Winnipeg to Edmonton line in 1904. As such, it is described as the oldest train station of this type still operating in Saskatchewan. Style-wise, it was built as a standard CNo class 3 station, but its demands as a divisional station meant that it was given an extended freight shed. It remains proudly at the head of the main street, which contains a large number of historic buildings. As a railway museum, it displays CN and pioneer artifacts.

Carman, Manitoba

The CNo station in this southern Manitoba community is categorized as a class 2 station. Larger than the rural stations, it presents wings on each side of the main building, each with a hip dormer. The wing to the west contained the waiting room, while that to the east was the freight room. It was built in 1902 and is today owned by the town of Carman. It was designated in 2003 as a Manitoba Municipal Heritage Site.

Dauphin, Manitoba

Although a “divisional” station, Dauphin’s is one of Canada’s finest examples of CNo station architecture. Built in 1912, and designed by the CNo’s architect R.B. Pratt, the brick-and-stone structure rises three storeys to its iconic pyramid roof. Two-storey extensions extend out from the central structure, each with low-gable roofs, while further single-storey extensions abut that. Small castle-like turrets adorn the corners of the third storey of the central segment. More fine examples of stonework are found not only on the base but at the corners of the walls as well.

Regina’s Union station is the third building to serve as a station in Regina. Following its closure, it became a popular casino.

The size of the structure reflects the site’s former importance as a major divisional point. The station was designated by the province of Manitoba in 1998 as a heritage resource and federally under the Heritage Railway Station Protection Act. It is now owned by the Town of Dauphin. Similar designs were created by the CNo in its Edmonton and Saskatoon stations, but these buildings no longer stand. A similar station, but with two pyramids, still stands in Thunder Bay, Ontario.

Gladstone, Manitoba

William Mackenzie and Donald Mann enlarged their railway empire by buying up the failing Manitoba and Northwestern Railway. They chose Gladstone as a divisional point and in 1901 built its standard class-2 divisional station here. It displayed the pyramid roofline and extensions to each side of the two-storey portion, where a pair of dormers punctured the roofline. As a divisional station, it also contained dining facilities for travellers. The building was relocated to the north end of the town and now serves as the community museum. The CPR had arrived in 1882 when it acquired the Manitoba and Northwestern Railway line from Portage la Prairie to Minnedosa. Gladstone’s station, to no-one’s surprise, is no longer around.

Hanna, Alberta

The Hanna station, another of the CNo’s prairie divisional points, was a standard class-2 building with the typical pyramid roof but also with extensions to each end of the structure. A prominent gable rests above the operator’s bay, and smaller dormers appear on the roofs of the wings. The station, closed in the 1970s, has been removed from its original location and now serves as a tourist information office near the west entrance to the community, from Highway 9. A rare historic roundhouse still survives, awaiting proposals for its preservation.

Humboldt, Saskatchewan

Sensibly designated as protected in 1992, under the HRSPA, the Canadian Northern station in Humboldt dates back to 1905. Along with its pyramid roof, more typical of the CNo’s rural class 3 stations, the station also features added wings to each end to accommodate extra passenger and freight traffic in this then-growing town. The CN vacated the structure prior to 2010 to move into newer facilities nearby. By late 2011, the building was empty and its streetside yard heavily overgrown, but the town of Humboldt is investigating alternative uses. The rail yards, however, remain very much is use, and yet contain a steel water tower.

Kipling, Saskatchewan

Built in 1909, the Kipling station is one of the class-2 divisional stations designed by the CNo’s early architect, R.B. Pratt. Larger than his standard rural station style, it contains wings on each side of the centre portion, each with a hip gable dormer above. The centre portion reflects the railway’s more typical pyramid roof, with prominent gables both front and back. Still in its original location, although turned around, the station was designated as a municipal heritage property and is now an attractive bed and breakfast.

Neepawa, Manitoba

Known to its early Cree inhabitants, Neepawa was, in their language, the “land of plenty.” The town’s growth dates from the arrival of the Canadian Northern Railway in 1902, when it chose this location for a divisional point and constructed one of its standard class-2 stations for such a busy spot. With its two-storey central portion topped off by the usual pyramid roof, wings extend to the sides, each displaying the hip-gable dormers of that style. The Beautiful Plains Museum moved into the vacant building in 1981, and the station still rests on its original site, although the tracks are now gone.

Radville, Saskatchewan

Built in 1912 by the Canadian Northern Railway to replace a temporary boxcar station, the Radville station was constructed according to that line’s plan 100-39, or class-2 style, and was one of only five such structures in Saskatchewan. It is typified by the CNo’s usual pyramid roof with extensions on each side of the main section. While the centre portion rises two full storeys and has a prominent gable above the operator’s bay window, the two wings have peaked dormers in the roofline. This is a divisional station on the CNo’s Brandon to Lethbridge route, and the building still occupies its original site.

With the switch from steam to diesel, the roundhouse was closed in 1960 and demolished soon after. In 1978 the last station agent retired and the station closed. Trains continued to use the grain elevators until the 1990s, but they, too, are now gone.

The CNo’s grand divisional station in Dauphin, Manitoba, is a spectacular example of R.B. Pratt’s design work. It is now owned by the town.

The Radville station, however, has survived and was designated as a heritage property in 1984. Still dominating the head of the main street today, it has become a museum. That main street also contains other heritage buildings, including an original hotel, formerly known as the Empire Hotel and now the Red Creek Saloon. Across from the saloon, the CIBC building was built as the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 1912, and it, too, is a designated heritage structure.

Stettler, Alberta

Built in 1911, this standard CNo 2nd-class divisional station, with its pyramid roof and extensions to both sides, now resides in the town’s Town and Country Museum, where various other heritage buildings have joined it. The original site of the station is now occupied by a more modern station, which serves as the boarding point for the popular Alberta Prairie Railway steam excursions.

Vermilion, Alberta

Located on the main line of the CNo, which built through this area in 1905, the railway chose Vermilion as a divisional point, and a roundhouse, water tank, and grain elevators were built. The standard 2nd-class divisional station rounded out the townscape. When the CNR decided to construct a new station, the old CNo building was moved a few kilometres west to Vermilion Provincial Park. The CNR maintains a busy yard at this location, having replaced the station with a smaller, more modern flat-roofed structure constructed of brick, with a dark trim around the roofline.

The Canadian Northern’s Country Stations

Ashern, Manitoba

Now serving as the museum office, the Canadian Northern’s simple single storey station in Ashern, labelled as plan 100-68, is the focus of a pioneer village. This includes a one-room schoolhouse, a 1912 Anglican church, a one-time post office, and a pioneer log cabin. The station was built shortly after 1910, when the CNo pushed its line north to Steep Rock and Gypsumville.

Avonlea, Saskatchewan

This history-conscious community south of Regina purchased its Canadian Northern station in 1981 and converted it to the Heritage House Museum. The CNo built this class-3 station, according to its common 100-29 plan, in 1912 on its Radville to Moose Jaw line. Increased traffic in 1917 prompted the railway to extend the freight shed, and the CNR later added its typical stucco finish to the exterior. It still rests on site, virtually unaltered both outside and in, and it displays the typical kitchen, living quarters, and waiting room of the station, as well as sports and law enforcement displays. The structure was one of the hundreds of rural stations erected by the Canadian Northern Railway that were dominated by the iconic pyramid roof.

Baildon, Saskatchewan

Situated in the unusual Sukanen Ship Pioneer Village Museum, the CNo’s 1911 Baildon station, one of that company’s standard rural stations, has found a new home along with the McCabe grain elevator and, as with a great many such museums, a caboose. More than three dozen heritage buildings line the streets of this heritage village.

The focus of the village, however, is Tom Sukanen’s “ship” — a vessel that he built in the prairie town of Macrorie, Saskatchewan, in the hopes that it would carry him, a homesick Finn, back to his homeland. During the difficult depression years, he brought in steel and wood and began to build the boat he would call the Sontiainen. Sadly, the ship was vandalized, and Sukanen ended up in a hospital in Battleford, where he died in 1943. For years, the remains of the vessel lay hidden in a nearby barn. Then, in 1975, thanks to a vigorous fund-raising drive, the vessel was moved to the Pioneer Village Museum south of Moose Jaw, where it was restored. In the end, the remains of the “crazy Finn” were re-interred next his beloved Sontiainen.

Baldur, Manitoba

Although it is lumped in here with the Canadian Northern stations, the Baldur station may be the only surviving example of a U.S. “northern plains” style station. There was no attempt at aesthetic or architectural embellishment: the wooden building offers only a gable roof and operator’s bay. No living quarters were here. The structure was built by the Northern Pacific and Manitoba Railway (NPM) in 1890 on a line initiated by the government of Manitoba, with the intention of combating the CPR’s unpopular monopoly on rail routes and grain prices. The strategy worked, and the federal government bought out the monopoly. But the NPM could not make much of a profit and sold the line to the upstart Canadian Northern Railway in 1900, thus launching that line on its way to becoming one of Canada’s major railway empires. As the station was built prior to the arrival of electricity, the brackets for the kerosene lamps remain visible in the building.

The station was moved to the Manitoba Agricultural Museum a short distance south of Austin, Manitoba, in 1975. The Homesteader’s Village contains twenty buildings, some of them replicas, that represent early settlement in Manitoba. Among them are the railway water tower from MacGregor, built in 1900, as well as a 1905–grain elevator from Austin. The village also contains a number of pioneer log buildings.

Bellis, Alberta

Using a standard Canadian Northern 3rd-class design, this station was built by the CNR in 1923 after it had assumed the operations of the bankrupt CNo. Relocated from the village of Bellis, the station is part of the Ukrainian Heritage Village, east of Edmonton. The interior has been restored to its 1950s appearance, complete with operating equipment and agent’s family accommodation on the second floor. A track runs in front of the station to a grain elevator a short distance away, thus recreating an early typical prairie railway landscape.

Blaine Lake, Saskatchewan

Built in 1912 on the CNo’s Prince Albert to North Battleford line, the station was a class 3 station, plan 100-29. The CNR ended operations in 1973 and sold the structure to the town, which now operates it as the Blaine Lake Museum. It is a municipal heritage structure and is listed on the Saskatchewan Register of Heritage Properties.

Bowsman, Manitoba

Here, in the Swan Valley Historic Museum, among an extensive collection of early area buildings, is the Canadian Northern Railway’s Bowsman station, built in 1900 prior to the arrival of the CNo’s new architect, Ralph Benjamin Pratt. The structure is a design from the CNo’s predecessor line, the Manitoba Railway, and consists of long hip gable roof with a peak gable dormer above the operator’s bay window. It was one of the last built by the CNo in this style prior to Pratt’s trademark pyramid-style stations. A bunk car rests on the grounds beside it, and a trapper’s cabin, shingle mill, and examples of pioneer tools are also on display here. Many of the surviving stations on the Gladstone to Swan River line were built by the Manitoba Railway before it was acquired by the CNo in 1901.

Carlyle, Saskatchewan

Located in a 1910 CNo 3rd-class station, the Rusty Relics Museum has an operational telegraph key on display. Nearby are a CPR jigger and a CNR tool shed. The station is an extended version of the usual class-3 rural station. The CNR line between Maryfield and Lampman is still in use.

Cereal, Alberta

This typical Canadian Northern class-3 station in Cereal, Alberta, was built by the CNo in 1911 on its Saskatoon to Calgary line. Relocated from its original site, it has been moved to another section of town and is now the Cereal Prairie Pioneer Museum.

Camrose, Alberta

The station in Camrose was one of a string built by the CNo in 1911 along its new line between that town and Stettler. Almost identical the other country stations, the Camrose station — experiencing increased traffic as the community grew — also features a more extensive freight and baggage wing.

In 1937 the CNR covered the wood-shingle siding, another typical feature of CNo stations, with stucco to provide more protection against the elements. This station is preserved as the centrepiece of Camrose Railway Park and houses the Canadian Northern Society library and archives, as well as a popular tea room. It was moved off its original site and placed on a more secure concrete foundation a short distance away. The CNo Society is responsible for helping to preserve much of central Alberta’s railway heritage, overseeing sites at Big Valley, Donalda, and Meeting Creek. The Morgan Garden Railway adjacent to the station contains a miniature railway and miniature replicas of local heritage buildings.

Donalda, Alberta

Although it sports the name “Donalda,” this museum is in fact a fine example of a Canadian Northern 4th-class station from Vardura, Saskatchewan. It was built in 1909 according to CNo plan 100-29. Following the removal of Donalda’s own station, in 1991 the Canadian Northern Society moved the building to Donalda, where the society undertook a restoration. This single-storey structure with a simple roof with gable ends contains the operator’s office at one end and the freight shed at the other. Its wood-frame exterior is painted in the more traditional Tuscan red.

A historic Canadian Bank of Commerce, built in either 1928 or 1932, houses the Donalda Art Gallery. The site also contains a historic creamery.

Edam, Saskatchewan

This small village still offers a genuine railway landscape, and its rural Canadian Northern Station faces a grain elevator that contains the displays of the Harry S. Washbrook Museum. The rails, however, are gone.

The CNo built the station in 1912 to its 3rd-class plan 100-12. It operated until 1979, when the CNR closed the station. Two years later, the municipality acquired the structure, making some interior alterations, although the exterior retains much of its original appearance. Since then, the Lions Club, a play school, and a community centre have occupied the building.

Fisher Branch, Manitoba

The station in Fisher Branch is another of the hundreds of rural CNo stations. It was built in 1915, closed in 1980, and is now the Rolling Memories Museum and a designated Manitoba Municipal Heritage Site. The structure has been modified slightly from its original appearance and is no longer near the tracks.

Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta

Founded as an RCMP outpost in 1875, the village remained a hub for the area’s Metis and First Nations people. Then, in 1905, the Canadian Northern Railway built its Edmonton line through the town, and Fort Saskatchewan boomed into a busy grain distribution centre containing an elevator and stockyard.

While displaying the typical CNo pyramid roof, the station is larger than most of its later counterparts and contains extended bellcast wings, a feature found on only a few other CNo stations, such as Humboldt and North Battleford in Saskatchewan. Known as CNo plan 100-19, it is the last of its kind in Alberta and is listed on the Alberta Registry of Historic Places. It has been out of service since the 1980s, and the building now serves as a museum.

Gravelbourg, Saskatchewan

When the CNo passed through southern Saskatchewan in 1913, it added a class-3 station in this established Francophone community, which had been founded years earlier by a Quebec priest who had led a party of Franco-Americans from New York state. After the station opened, the CNo provided twice-weekly passenger service until the 1950s.

When harvests failed during the drought-stricken thirties, the CNR brought relief supplies to the community, and when grain harvests were bountiful, it brought it trainloads of harvesters on what were known as the “Harvester specials.”

From 1987 until 1997, the station served as the town office. Today, it stands at its original site, although turned around, and is now a residence. In 1987 the branch was absorbed into the CPR system, which still operates the line and hauls grain from the town’s two remaining elevators.

Gilbert Plains, Manitoba

One station that employed a less-common style is the CNo station in Gilbert Plains. Built in 1900, it offers hip gables at each end with a peak gable above the operator’s bay window. It is now a seniors drop-in centre at Main and Gordon Streets, close to its original location.

An identical station, originally built in Bowsman, is now at the Swan Valley Museum in Swan River. As with the CNo Winnipegosis station, this style predated Pratt’s arrival.

Langham, Saskatchewan

This former CNo 3rd-class, plan 100-39 station in Langham, built in 1905, became the community’s museum in 2001 and is situated close to its original location on Railway Street. The freight shed is an extended version of the standard shed. Shared with the Wheatland Library, the displays include household artifacts and the “flour sack story”: what the ingenious pioneers were able to create using simple flour sacks.

Lundar, Manitoba

Still on its original site, although turned around now, the Lundar station is another of those typical CNo class-3 stations. Located north of Winnipeg on the branch line that led to Gypsumville, the building is now, like so many others, a museum. This heritage village offers visitors the Mary Hill School, the Notre Dame church, two log houses, and an Icelandic library. The focus is, of course, the railway, and the grounds include the former CNo railway station as well as the usual caboose

Maidstone, Saskatchewan

This rural CNo class-3 station with an extended freight shed was relocated in 1990 to 2nd Street, where it is the focus of the Maidstone and District museum, along with the usual caboose and other heritage buildings, such as a barber shop, store, and church. It was built in 1905 on the CNo’s main line between North Battleford and Lloydminister and operated until passenger service ended in 1977. In 1989 the Province of Saskatchewan designated it as a heritage property.

McConnell, Manitoba

This standard CNo class-3 rural station was built in McConnell on the Beulah Halboro branch in 1909. Following its closure, it was heavily vandalized until it was rescued by the town of Hamiota and moved to the Hamiota Pioneer Club Museum grounds on 7th Street. A historic church has been moved from Oakner to the grounds as well. The abandoned rail line has become a recreational trail.

McCreary, Manitoba

This is another typical Canadian Northern small town station, built in 1912 on the Dauphin to The Pas line, according to plan 100-29. It retains many of those original features, including the steep pyramid roof devised by R.B. Pratt and a grey-stucco exterior applied in the 1930s by the CNR. The railway closed the building in 1980s, and in 1991 the province designated it as a provincial heritage property. The town purchased the building in 1997 to develop it as a museum

Meeting Creek, Alberta

This community is another example of a genuine surviving prairie heritage railway landscape. With its nearby grain elevators, the village of Meeting Creek presents a true vestige of the Prairies’ railway heritage. The station was built by the Canadian Northern Railway in its class-3 rural style. In 1911, urged on by Premier Alexander Rutherford, the CNo extended its tracks between Camrose and Stettler, bypassing the original settlement of Meeting Creek by eight kilometres. As was usually the case, the village moved closer to the station. The first train to reach town was greeted by the local band

Although the station fell silent in the 1960s, it remained standing and in 1988 was converted by the Canadian Northern Society to an interpretative centre and restored to resemble its 1950s appearance. A small wooden trestle still exists a short distance west of the station and grain elevators.

In 1997 the branch line’s owner, the Central Western Railway, abandoned the line, but in so doing donated enough trackage to ensure the preservation of this genuine prairie railway landscape.

Miami, Manitoba

The structure in this southern Manitoba community predates many of the surviving stations in this province. In fact, it was built as early as 1889 by the Northern Pacific and Manitoba Railway Company (NP&M) and shortly thereafter acquired by William Mackenzie and Donald Mann to help launch that duo’s monumental railway empire.

The station is the sole survivor of three built in this rare style by the Northern Pacific and Manitoba Railway in 1889. Before the arrival of the Canadian Northern Railway, the NP&M was one of the first railways to challenge the CPR’s dominance in western Manitoba. The unusual two-storey building sports hip end gables and an observation bay on the second floor, directly above the operator’s ground floor bay window. It is the only surviving station with such a feature.

Moved slightly from its original foundation, the Miami station was designated as a municipal heritage structure in 2008 and today houses a museum.

Moosehorn, Manitoba

The simple single-storey CNo station, built to one of that line’s 4th-class plans (plan 100-68) now rests next to the Moosehorn Heritage Museum, which is housed in a historic Masonic Hall. The agent’s quarters were located at the rear of the building instead of the second floor.

Norquay, Saskatchewan

Situated northeast of Yorkton near the Manitoba border, the village of Norquay sprang to life when the CNo arrived in 1911 and constructed one of its standard rural class-3 stations. Settlers, including ranchers and lumber men, had begun arriving earlier when the CPR reached Yorkton in 1898. Located close to its original site, the building is now the Whistle Stop Restaurant.

The CNo station and the grain elevators at Meeting Creek, Alberta, reflect a true prairie railway landscape.

Prairie River, Alberta

Now a museum, the Prairie River CNo station was designated as a municipal heritage property in 1982 and since 1985 has served as the Prairie River Museum. The collection displays artifacts depicting pioneer and aboriginal life in the area, as well as a railway saw mill and planer, which operated until 1917.

The CNo erected this station in 1919 even as the company’s corporate health was failing. In fact, the building was transferred to the Canadian National Railway (CNR) later that year. The station was listed as CNo plan 100-72, a common later design for 3rd-class stations used in small communities across the province. The station is listed on the Saskatchewan Register of Heritage Properties.

Roblin, Manitoba

In 1906 the CNo built one of their standard 3rd-class stations to plan 100-3 in this community. On the main line from Winnipeg to Edmonton, the extra business in the area required a longer than normal freight shed.

The station closed in 1978 and is now a popular Austrian restaurant known as the Station Café. In addition to serving food, the restaurant has replicated the agent’s office and displays railway memorabilia. Its exterior has been little-altered, save for a paint job. It remains on its original site, although no yard buildings remain.

Rowley, Alberta

This CNo 3rd-class station helps to form another one of the Prairies’ better railway heritage landscapes. Not only does the structure remain on site, it has been preserved as a station. One of the last of the plan 100-72 CNo stations, it was built in 1922 on the Stettler subdivision. Rowley is also a ghost town attraction, and, because it has attracted filmmakers, it is nicknamed “Rowleywood.”

St. James, Manitoba

This single-storey structure was built in 1910 by the Canadian Northern Railway at the west end of Winnipeg and was part of the line’s Oak Point Subdivision. The structure is a CNo 4th-class single-storey rural station.

In 1974 the Winnipeg’s Vintage Locomotive Society acquired the historic building to use as their boarding point for the popular Prairie Dog Central Railway steam and diesel excursions. With the abandonment of the subdivision by the CN in 1996, the society moved the station to a more rural location on Inkster Boulevard, where it continues to play out its important heritage role. Designated as a federally protected station, its ticket office, two waiting rooms, and freight rooms have been restored to reflect its historic train operations. The Prairie Dog Central Railway steam locomotive can often be seen puffing impatiently in front.

St. Walburg, Saskatchewan

Although constructed by CNR in 1922, this 4th-class design was first introduced by the Canadian Northern Railway in 1907 as plan 100-68. The CNR modified the design somewhat after assuming control of the CNo. According to the Saskatchewan Resister of Heritage Properties, it was one of over seventy stations of this basic style constructed in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Minnesota. It lacked second-storey living accommodations.

The building is now used as an interpretative centre.

Shellbrook, Saskatchewan

Settlers began arriving into the Shellbrook area as early as 1882. Even by 1905, there was little more than a general store and post office. In 1909 the CNo laid out the townsite and built one of their standard class-3, plan 100-29 country stations. As business improved, the freight shed was extended, and later, in the 1930s, the CNR applied a coating of stucco to the exterior. The first train of the CNo arrived in January of 1910.

The station has become a museum, and happily it remains on site at the foot of the main street, where it faces a small “elevator row.”

Smokey Lake, Alberta

In 1919, as one of the Canadian Northern Railway’s last acts of railway building, it extended a line from Edmonton in a northeasterly direction in order to open settlement lands for returning First World War veterans. Known as plan 100-72, a slightly larger version of the CNo’s 3rd-class stations, the station in Smokey Lake is nonetheless nearly identical in appearance to the hundreds of other CNo stations erected across the prairies, and like those others it owes its design to R.B. Pratt.

In 1936 the new owners, the CNR, covered the wood-shingle siding with stucco and repainted the station in its standard green-and-yellow paint scheme. Following the closing of the station and the removal of the tracks, the building was moved a few metres back from the now vacant right of way, while a caboose rests on a section of track nearby. The right of way now forms part of the Iron Horse rail trail.

Sturgis, Saskatchewan

In 1911, when the tracks of the CNo finally reached Sturgis from Pelly, a box car served as the first station. When the line arrived from Canora in 1914, the railway added another of its later standard rural class-3, plan 100-72 stations, and the village became the leading cattle shipper in eastern Saskatchewan. The CNR used the structure until 1984, when the railway indicated its intention to demolish it. Worried about losing their most significant heritage structure, residents of Sturgis formed a committee of volunteers and raised funds to relocate the building a short distance away. Today, it functions as a museum and displays many elements of the history of the town and its area, including farm and household items and the obligatory caboose.

Turtleford, Saskatchewan

This standard class-3 CNo station, built on the North Battleford to Turtleford branch, has been relocated to become the district museum. Intended as a loop line between North Battleford and Edmonton, the route was meant to help open the territory north of the North Saskatchewan River to settlers. The Saskatchewan end of the line reached Turtleford from North Battleford in 1914, but the demands of the First World War suspended the work. By the time construction resumed in 1919, the CNo was no more. The CNR, which had assumed control of the CNo, managed to extend track from Turtleford to St. Walburg in 1921, but the western section was halted at Heinsburg in 1928. The vital gap was never filled.

Wadena, Saskatchewan

This 3rd-class CNo station, the most common style on the prairies, was built by John Skoglund in 1904, and passenger service began the following April. When the CPR built its line across the tracks of the CNo, the station was moved twenty-five metres to the east.

The CNR halted passenger service in 1963 and by 1981 had closed this station. In that year, the municipality purchased the building and moved it to the south end of the village, where it is now the focus of the town’s heritage village. The site includes rail artifacts such as a hand car, crossing signals, a telegraph wire, and the omnipresent caboose. The grounds also contain a Mountie barracks, a 1914 homestead, and a historic school house. Wadena’s CPR station is also well-preserved and is now a private home west of the community

Waldheim, Saskatchewan

Although Mennonite settlers had begun arriving as early as 1893, the CNo did not lay tracks here until 1909, when it erected its typical rural class-3 station on its Carlton Subdivision north of Saskatoon. Still on its original location, the town acquired the building in 1983 and it now houses a library and museum.

Winnipegosis, Manitoba

Before the CNo lured station architect Ralph Benjamin Pratt away from the CPR, the CNo’s earlier stations in Manitoba offered a different appearance. Hip gables marked the front and rear, a two-storey roof over the operator’s bay window. In the Winnipegosis station, a pair of extensions stretch from each side of the ticket office, one housing a waiting room and the other, the freight room. Each extension sports similar hip gables on the ends of its two wings. Similar structures also stood in Manitoba at Swan River, Ochre River, and Ethelbert.

Built in 1897, this large station is now the home of the Winnipegosis Museum, a project of the Winnipegosis Historical Society. The grounds also contain the vessel Myrtle M., built in 1938 to serve the Lake Winnipegosis fishing industry.

The GTP Survivors

As with the CNo, the Grand Trunk Pacific used only a limited range of railway station patterns. While the country stations varied slightly in the shape of the gable and bay, the original divisional stations generally copied the same styles used by its sister rail line, the National Transcontinental Railway, east of Winnipeg. These were large two-storey structures, some of which held a prominent gable midway along the roofline, while others had cross gables at each end of the roof. A few were half-timbered to reflect a tudoresque flair. The only survivor of this style is at Melville, Saskatchewan, and replacement division stations built by the CNR were simpler in style. The GTP built only one main line across the prairies and few branch lines. As a result, few stations remain, since few were ever built.

Divisional Stations

Biggar, Saskatchewan

Wadena’s CNo class 3 station is now a museum.

In February 1996, Sheila Copps, federal minister of heritage, arrived in Biggar to declare its historic GTP station “protected” under the Historical Railway Station Protection Act.

At the time it opened in 1910, the GTP station in Biggar was considered the largest GTP station in the west. The building displays a simple elegance, with a steep bellcast roof and prominent gable above the operator’s bay window.

In 1986 the dispatching system was automated and passenger service ended. In that year, the station closed. With five hundred railway workers and the confluence of three GTP lines as well as a CPR line, the town was totally railway dependant. In many ways it still is. A new CN bunkhouse was built for the 150 CN employees and stands opposite the “protected” station.

Regrettably, that heritage building is suffering from demolition by neglect. Following its new designation, it remained unused and rotting. By late 2011, portions of the overhang were falling off, while large bushes pushed through the cracks in its foundation.

This view of the Biggar station shows that even federal designation cannot save a station from neglect.

Melville, Saskatchewan

When the GTP designed its divisional stations, it opted for a large structure. Melville’s station, built in 1908, was one of a handful of such designs on the GTP/NTR line and was built by Carter Hall and Adlinger. The original divisional station in Rivers, Manitoba was identical to this style, as is the one still standing in Sioux Lookout, Ontario.

The building is a full two storeys with half-timbered gables on the roof over the operator’s bay, and another gable at the end, as well as another set on the town side. As with most divisional stations, that in Melville contained a restaurant, which was known as the Beanery. Proposals for its reuse have included converting it to a Western Hockey Hall of Fame. Throughout 2011, volunteers were hard at work cleaning up the interior. As is typical in a prairie town, the building dominates the foot of the main street. A GTP station imported from Duff now sits in the Melville Regional Park, along with a steam engine (see museums).

Rivers, Manitoba

In 1908, as the GTP main line proceeded across the prairies, the company chose Rivers as a divisional point and here built a station using the same overall plan as that found at Melville. As was its practice, the GTP named the station after one of its own: President Sir Charles Rivers-Wilson. A full two storeys, the station displayed the two cross gables at the ends of the building and a bay window at the east end. The yards contained a roundhouse, a repair shop, and coal shed. In 1917 the GTP replaced it with a new storey-and-a-half station with a wide bellcast roof and half-timbered, stucco-covered gables on both the track and street sides. But, with the advent of diesel, the steam facilities were no longer needed, and all structures associated with the station’s divisional role — the water tower, the roundhouse, and the bunkhouse — were removed. Only a few sidings remain in the once busy yards.

Today, the solid-brick station, although federally designated as a protected heritage station, is vacant and falling into disrepair, but it is not as seriously damaged as in the station in Biggar, and a local community is working to restore it. VIA passengers now use a small shelter transported to the location from North Brandon.

The GTP’s grand Melville divisional station is in the early stages of restoration.

The Country Stations

Delburne, Alberta

This central Alberta Community has preserved its standard-plan Grand Trunk Pacific station as well as its wooden water tower. The tower contains four levels of displays, including a replica coal mine and a school room, all on the grounds of the Anthony Henday Museum. This station varies from other GTP country stations in that the operator’s bay window and the dormer immediately above it, the agent’s apartment, are octagonal in shape. Also on the grounds is a CN caboose.

Edgerton, Alberta

Here on the grounds of the Edgerton and District Museum, the 1909 GTP station (plan 100-152), relocated from its original site, houses a rare collection of autochrome photographs taken by Hugo Viewager between 1913 and 1914. The grounds also include the Battle Valley and Edgerton Methodist Church, as well as a display of older autos and tractors. The station is located at Highways 894 and 610.

Edson, Alberta

Edson sprang into existence when the GTP extended its line west of Edmonton in 1911 and named the location after Edson Chamberlain, the line’s general manager. The Edson station also marked the location of the Alberta Coal Branch, as well as being a jumping-off point for settlers en route to their homesteads in the Grande Prairie region. Representing a simpler version of the standard-plan stations, plan 100-153, this station had its roof modified when it was moved to Centennial Park in 1975. Now named the Galloway Station Museum, its displays include railway and coal-mining artifacts. Funding from three levels of government helped upgrade the museum, which held its grand opening on September 25, 2011. The Museum is operated by the Edson and District Historical Society.

Evansburg, Alberta

Tipple Park is appropriately named, as the town of Evansburg was one of Alberta’s earliest coal mining towns. It dates to 1907, when coal was first extracted, but the lack of a railway hindered economic shipments. At first, as the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway built its tracks west from Edmonton in 1909, it ended its tracks at Entwhistle on the east side of the Pembina River opposite Evansburg. The gorge was too difficult to quickly bridge, and it would take until 1912 before one was complete. As a result, the two communities boomed. Although the stations from both towns no longer stand, that from MacLeod River was moved to Tipple Park, where it is now the heritage centerpiece … along with a caboose. It is a standard-plan GTP single-storey small town station with an octagonal dormer and bay window.

Fort Qu’Appelle, Saskatchewan

Located at the convergence of several early trails, the site attracted a Hudson’s Bay trading, an RCMP fort, and a mission. The trading post, dating from 1897, still stands. Its railway story would have had more significance had the CPR followed through with its original plan to construct its main line across the valley in this location. Instead, the CPR opted for Regina — a less attractive location but one where flatter terrain meant lower costs.

In 1911 the GTP reached Fort Qu’Appelle with a line connecting Melville with Regina and Northgate on the North Dakota border. It was one of only a few branch lines constructed by the GTP. The railway built an extended version of its standard plan 100-152 rural station with the polygonal dormer rising above the bay window. Unlike others of this plan, the bay and the dormer lie in the centre of the structure. Still on its original site, the station closed in 1962 and is now a tourist information office.

Nokomis, Saskatchewan

The Grand Trunk Pacific, on what began as the Qu’Appelle, Long Lake and Saskatchewan line, built a station identical to the CPR’s standard plan #10 pattern. The building was moved to the present site on Highway 5 in 1977, where, along with a caboose, it is the focus of the Nokomis and District Museum.

Portage la Prairie, Manitoba, CN/VIA

This sturdy station was built by the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway in 1908 on its main line from Winnipeg to Saskatoon. Originally a “union” station serving both the GTP and the Great Northern Railway of Manitoba, it was built in a style different from most of its GTP contemporaries. In fact, it may well have been influenced by the GNR. It is a long, single-storey brick building with a low, wide-flared roofline and a pair of gables on both the track and street side, including one above the operator’s bay and one over the entrance. The station is still in railway use and a is stop for VIA Rail on both its transcontinental and Churchill trains, as well as for interurban buses; it lies only a few metres from the equally historic CPR station. The CNo also built a station nearby, but it burned down in 1960.

Three Hills, Alberta

Now the focus of the Kneehill and District Museum in Three Hills, this GTP station may have been one of the last built by that failing line. Dating from 1919, it displays a square dormer above the operator’s bay and an unusual recessed dormer at the end. This was the railway’s plan 100-151, one of only a dozen built in the prairies. These dormers reflect the agent’s living quarters. A caboose sits in front of the station.

Viking, Alberta

The Grand Trunk Pacific station was built in 1911 to the GTP’s plan 100-154. The roofline includes square dormers, both at the end and above the operator’s bay, which too was square. It remains near its original site in and is now known as the Viking Station Gallery and Art Centre. It is located on 51st Street. The location is also a flag stop for VIA Rail’s transcontinental train, The Canadian.

The CNR Survivors

When the CNR assumed operations of the Canadian Northern and Grand Trunk Pacific railways, they initially used existing stations. Once the CNR began to extend its own branch lines, it adopted a distinctive style for its rural stations: a boxy, two-storey structure with little embellishment. Its divisional stations, however, tended to demonstrate more flair and imagination.

The CNR, through the 1920s, took on the ambitious task of completing the on-again off-again line to Churchill on Hudson’s Bay; prairie farmers had long lobbied for their own access to a prairie grain port. While that line does not traverse the usual prairie grasslands and wheat fields, this connection to the Prairies’ economy and culture brings it and its railway features into the fold of Canada’s prairie railway heritage.

Divisional Stations

North Battleford, Saskatchewan

Battleford, Saskatchewan, is one of the province’s most historic sites. Here, Fort Battleford was built to house the North-West Mounted Police to help keep the peace in this troubled area. In 1876 it was designated as the territorial capital. After it lost that role to Regina in 1883, a depression set in until the CNo indicated that it was forging its main line along the banks of the North Saskatchewan. But then depression returned when the residents learned that this new railway divisional point would be on the opposite side of the river and would be of no use to them at all.

The GTP eventually did bring a line through old Battleford, but it was too little, too late, and the station was little more than their typical country depot. The GTP linked with CNo north of the community at Battleford Junction. When the CNR assumed both lines, it removed the former GTP portion. Today, of course, the two communities are completely linked and are known as “The Battlefords.” Government House still stands and it, along with the fort, are national historic sites.

The solid brick station in this historic community is another one of the few constructed by the Canadian National Railways during the 1950s. The style is known as the International style and consists of a flat roofline and modernistic raised aluminum lettering. A second floor houses staff offices for the divisional yard in front of the station. In 1995 the building was designated as a protected station under the Heritage Railway Stations Protection Act.

It replaced a standard CNo class-2 divisional-point station. That station, built in 1911, was moved to 22nd Street to become the Pennydale Junction Restaurant. Although a divisional station, it looked very much like the more typical 3rd-class stations with the pyramid roof rising above the two storey central section. It differs in that two wings extend to the sides and display wide, low, bellcast rooflines. The CNo built a few of its divisional stations to this style, such as that at Humboldt. The facade of the old station has been significantly altered.

East of the station, the Western Prairie Development Museum contains the relocated CNo 4th-class station from St. Albert, Alberta, as well as a steam locomotive with box car and caboose appended.

Prince Albert

Originally a terminus for the Qu’Appelle, Long Lake and Saskatchewan Railway (QLL&S) in 1889, this line linked the growing cities of Regina and Saskatoon with the steamers on the North Saskatchewan River, at what was then the mission village of Prince Albert. The first station, built in 1891, was a standard QLL&S wooden hip-gable style. The line was operated by the CPR until the CNo acquired the route in 1906 and built one of its standard class-2 divisional point stations. Later, the busy yards developed further when the CNo also extended its line from Hudson Bay, Manitoba, through Prince Albert to Shellbrook in 1910.

The CNo had originally intended that Prince Albert be on its main line but instead opted for a more southerly route from Gladstone in Manitoba directly to Edmonton. The CPR didn’t leave town entirely, though, and it ran its trains along the CNR line from Hague. The Grand Trunk Pacific extended its line northward from Young, reaching St. Louis in 1914 and Prince Albert in 1917, and the town appeared poised to become a significant rail hub for northern Saskatchewan. Through the 1990s, both the CN and CP gave up their routes, abandoning many of their branch lines out of Prince Albert. Meanwhile, the CN line from Hague was acquired by Omnitrax as the Carlton Trail Railway (CTR) short line. The former CNR station was built in the 1950s in the modern international style as a two-storey flat-roofed structure with raised aluminum station letters, and it now serves as a business office, while the roundhouse, built in 1959, still provides repairs for the CTR.

Vegreville, Alberta

Unlike most prairie stations, the one in Vegreville was added by the Canadian National Railway itself. After having assumed such bankrupt rail lines as the Grand Trunk Pacific and the Canadian Northern, the CNR simply opted to recycle existing station buildings. However, when the rival CPR extended a branch line through Vegreville, the CNR replaced the earlier Canadian Northern station with a larger one. Built in 1930, the new Vegreville station incorporated separate men’s and women’s waiting rooms as well as washrooms and then built a smoking room.