Chapter Seven

Watering the Steam Engines: The Water Towers

Another railway fixture that is scarcer than railway stations is the railway water tower. Because most steam engines had a limited capacity for the water they needed to carry, anywhere from two thousand to eleven thousand gallons, the railways placed water towers at sufficient intervals for the trains, usually at every other station siding, or thirty to forty kilometres apart. Smaller engines usually could not go beyond eighty kilometres before filling up. Because even the largest towers held no more than 180,000 litres, there needed to be enough water close by to keep the towers full.

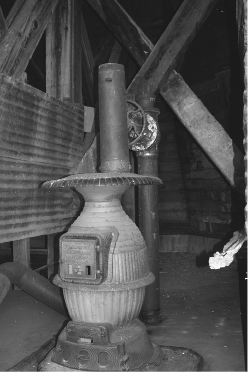

The most common style of water tower was the wooden octagonal tower, a few of which still survive. The next most common was the steel tower. Both types needed a source of warmth inside to keep the water from freezing, usually in the form of a stove. To determine how much water remained in the tank, a float that supported a rod that extended through roof and had a ball on top was used, giving a visual from the outside as to what remained. With the building of larger steam locomotives after 1920, with their larger capacities, fewer water towers were needed. Finally, the era of the diesel engine eliminated the need for them at all, and most were demolished, generally unfit for re-use. Where they do survive, they form a rare component of the Prairies’ railway heritage

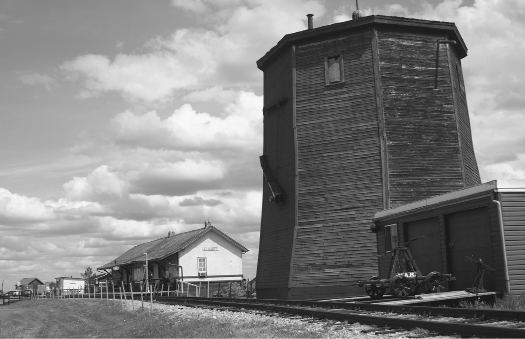

At the Alberta Railway Museum, visitors can explore the interior workings of a rare surviving water tower.

Alberta

Heinsburg

Located in eastern Alberta, the water tower in the “ghost town” of Heinsburg was built by the CNR in 1928 in what was the branch line’s eastern terminus. The tower has been restored by members of the community, as has the CN station. Both remain on their original sites.

New Brigden

Built by the Canadian National Railway in 1925, the New Brigden water tower was, like the others, an engineering marvel. Constructed entirely of wood and covered with shipslab siding, the tower is the tallest structure in this small village, at thirteen metres high. Like other similar water towers, the water level inside could be read by means of a float. To prevent the water from freezing, the inner tank rested on twelve vertical timbers about 5.5 metres above the ground and was heated by a stove. While tracks and station are both gone, the New Brigden tower alone celebrates the community’s railway heritage. It was designated in 2009 as a municipal heritage resource.

Other surviving towers in Alberta include steel towers beside the site of the Bassano station, and, in the Humboldt yard, the 1919 wooden water tower from Gibbons, which is now in the Alberta Railway Museum north of Edmonton. There is also the GTP’s Delburne water tower, which moved to the Anthony Henday Museum beside the former GTP station.

Manitoba

Glenboro CPR Water Tower

Just as the railway company had standard designs for their stations, so too did they have “plans” for their water towers, and those in Glenboro and Clearwater went by “Plan 1.” They were among seventy-five such towers built along the CPR lines throughout Manitoba. Although they have been out of use for decades, ever since the CPR and other railways converted their locomotives from coal to diesel, they were designated as provincial heritage sites in 1993. The Glenboro tower was then owned by the town but sadly torched by arsonists in April 2008.

Clearwater CPR Water Tower

The water tower in Clearwater Manitoba is identical in style and age to that which stood in Glenboro. Like the Glenboro tower, it was designated as a provincial heritage structure. This 180,000-litre tower still retains its motor and pump, which were used to prevent the water from freezing. It is owned by its local municipality of Louise.

WinnIpeg Beach

The railways realized that with the natural riches along their lines, such as the Rocky Mountains, they could profit from recreation. In 1910 the CPR acquired sixty hectares of land on Lake Winnipeg and established a resort complex of accommodations as well as recreational and amusement facilities. To provide water to its resort and for its steam locomotives, in 1928 it constructed a steel water tower that was forty metres high and had a ninety-thousand-litre capacity. On busy summer weekends, as many as forty thousand excursionists would crowd onto the trains for the sixty-five-kilometre run from Winnipeg to the popular amusement park. But in 1964, the park closed and the water tower fell into disuse. Today, it still stands and is a designated heritage landmark. With its steel tank resting atop the four steel legs, it is the only one of five original such structures surviving in Manitoba.

Many water towers have made their way into museums across the prairies. The tower from McCreary, a standard wooden structure with a 180,000-litre capacity, rests on the grounds of the Manitoba Agricultural Museum in Austin. A steel water tower still stands by the tracks in Carberry.

The water tower and station at the Alberta Railway Museum offer a glimpse of a vanished landscape.

Saskatchewan

Glaslyn

Perhaps the reason that the 1926 CN water tower in Glaslyn had remained in such good condition is that it continued to supply water to the town until 1993, when a new municipal water tower began operation. Today, the preserved tower, along with the CN station, is part of the Glaslyn Museum and forms one of the truest railway landscapes on the prairies.

Hague

In 1903 the CNo extended its tracks through Hague, Saskatchewan, and built one of its many water towers. Unlike the usual tapered towers favoured by the CPR, that at Hague is vertical. The overall structure extends eight metres high and could contain the usual 180,000 litres of water. The inner tub, which contained the water, is made of three-inch cedar and supported by five-metre-long square timbers and extends seven metres high. Now repainted a bright red, it still rests by track and is a proud visual symbol of this railway community.

At Glaslyn, Saskatchewan, the CN station and railway water tower have been preserved on their original sites.

Harris

Built by the CN in 1934, the Harris water tower, like many railway buildings, had a plan number, that being 150-99, one of only nine built in Saskatchewan. The eight-sided tower could contain 180,000 litres. During the days of steam, an estimated five hundred such water towers once dotted the prairie landscape. Threatened with the emergence of diesel power, the Harris water tower was relocated. With much of its interior workings intact, the structure is now a municipal heritage site. It is located beside the Harris and District Museum on Railway Avenue near Highway 7. A CN caboose also stands on the site.

Kenaston

It is always refreshing to witness a small community undertake the restoration of a scarce railway feature. In 2009 the town of Kenaston completed the restoration of its 1910 CNo water tower. This typical structure was constructed of wood, tapered, and capable of containing 180,000 litres of water for the steam locomotives. The restoration involved a new foundation, repairs to the exterior, and repainting the tower its original tuscan red and cream colours. It is now a tourist attraction on the Louis Riel Trail tourism corridor and is one of only five such towers in that province, three which remain on-site.