Everything was going fine till we reached Passport Control. There were two booths in front of us, each manned by a sternlooking border guard. Thimble went right, I went left. The guard checked my passport, then my face, then showed the passport to a machine.

At this point I had a strange sensation. Something was tickling the side of my face. I raised my hand and grasped something woolly.

Yikes! Thimble’s tail! It must have broken free of his trousers!

There was no time to lose. Quick as a flash, I bent the tail over my top lip and tried to look as innocent as possible.

The guard’s eyes rose. A look of confusion came to his face. He checked the passport, then me, then the passport again.

‘You didn’t have that moustache a minute ago,’ he said.

‘It grows fast,’ I blabbed.

‘You’re not old enough to grow a moustache!’ he replied.

‘Run, Thimble!’ I cried.

In a trice the moustache had vanished from my face and I was following Thimble helter-skelter through the departure lounge. Sirens were going off all around us and men with guns were appearing everywhere.

‘Mum!’ I cried.

A distant voice replied, ‘Yes, love?’

‘Where are you, Mum?’ I cried.

‘Right here,’ said Mum, ‘with your milk.’

Sure enough, there was dear Mother, wearing her dressing gown, holding my even dearer morning milk.

‘Had a bad dream, Mum,’ I said.

‘Never mind,’ said Mum. ‘You’re back in real life now. Come and help me shave Thimble’s face.’

Two hours later, the keys to Dawson Castle were under the flowerpot, and we were on our way to 33, Rue de Fou, Blingville. I knew the address because it was my job to remember it, which was easy, as 44 was Mum’s age, and it was exactly eleven years less. It was hard to contain my excitement, and even harder to contain Thimble’s. He could not get used to having no tail and every few minutes did a sudden about turn in hope of taking it by surprise. Sadly, however, his tail was too smart for him, especially with ten strips of gaffer tape sealing it to his underpants.

Everything was going fine till we reached Passport Control. There were two booths in front of us, each manned by a stern-looking border guard. I went right and Thimble was about to go left when Mum swung him round in front of me.

‘Let’s all go through together,’ she said.

The border guard took Thimble’s passport, stared hard at it, then at Thimble. Then the passport again, then Thimble again. She frowned hard, as if dealing with some insurmountable problem.

‘We’re in luck,’ said Mum. ‘Prosopagnosia.’

‘Wow,’ I said, ‘what’s that?’

‘Face blindness.’

‘Face blindness?’ I repeated. ‘What’s she doing working in passport control?’

‘Nepotism,’ said Mum.

‘How do you know?’ I asked.

‘I’m omniscient,’ said Mum.

I’ll leave a little break here so you can check a Glossary of Long Difficult Words. Mum has a degree in English Literature and likes to talk to me as if I have one too.

It was late and quite dark when we arrived in Blingville. You could tell we were in France because everyone was speaking French, even the taxi drivers. As usual in these situations, Dad took control. Dad was proud of his command of the French language. For some strange reason, however, the taxi drivers refused to understand a word he said and turned to Thimble instead, whose sign language is international. So it was Thimble who booked us a taxi, me who showed them the address scribbled in my notebook, and Mum who sat in the front chatting and, for some strange reason, being understood perfectly well.

Yes, everything was looking ticketyboo, especially when we arrived at 33, Rue de Fou and found a magnificent villa with a front garden bigger than the whole of Dawson Castle. Grapes were cascading over the front wall and, just as Serge and Colette had promised, there was a grey wheelie bin alongside the front door.

‘The keys should be taped inside the lid,’ said Mum.

Dad checked. ‘No keys here,’ he grunted.

‘Perhaps they’ve fallen inside?’ suggested Mum.

Dad checked inside increasingly frantically, finally turning the bin upside down and shaking it like a tambourine.

‘I knew this home swap was a mistake!’ he cried.

‘That is strange,’ said Mum. ‘Serge and Colette did not seem like the kind of people who would forget to leave the keys.’

‘We don’t even know them!’ railed Dad.

‘We’ve exchanged emails.’

‘That’s all we are going to exchange,’ said Dad.

‘Maybe there’s a way in round the back,’ said Mum.

We made our way down the drive, which seemed to go on forever, till we reached the back of the house. There we found a terrace with a huge outdoor table and fancy curly chairs. Beyond that was a garden of scorched grass in which there was a gigantic trampoline, a colossal swimming pool and a mammoth tree house. It was a garden beyond my wildest dreams.

‘Maybe we could just live here,’ I suggested.

Dad did not seem to hear me. He was rattling the shutters that covered the French windows and checking if there was any way to climb up to the first-floor balcony.

‘Wow,’ said Mum. ‘This really is swish. I hope they’re not disappointed with our bungalow.’

‘At least they can get into our bungalow!’ replied Dad.

‘Hang on,’ said Mum. ‘There’s an open window.’

I followed Mum’s pointy finger. Yes, there was an open window, at the very end of the house. But it was a very small window, probably the window to a toilet.

‘We can’t get through there,’ said Dad.

‘Thimble could,’ said Mum.

I called Thimble, who by now was dangling from the tree house.

‘Thimble,’ I said, ‘listen very carefully. We want you to climb through that window, then open one of those big windows and let us in. Do you understand?’

Thimble nodded enthusiastically.

‘He understands.’

‘He nods whatever we say,’ said Dad.

Thimble nodded enthusiastically.

‘Heaven help us,’ said Dad.

I gave Thimble a leg up, not that he needed it, and he scrambled through the window with the greatest of ease. A few seconds passed. Then a few more. Then a few minutes. Then a few minutes more.

‘Perhaps there aren’t any keys,’ I suggested.

‘This kind of window is usually locked with a handle,’ said Mum.

‘If we could just get … these … shutters…’ grunted Dad, heaving with all his might at the great wooden window guards.

‘Try lifting the catch,’ said Mum. She raised a metal catch and hey presto, the shutters folded back and we had our first glimpse of the interior of 33, Rue de Fou.

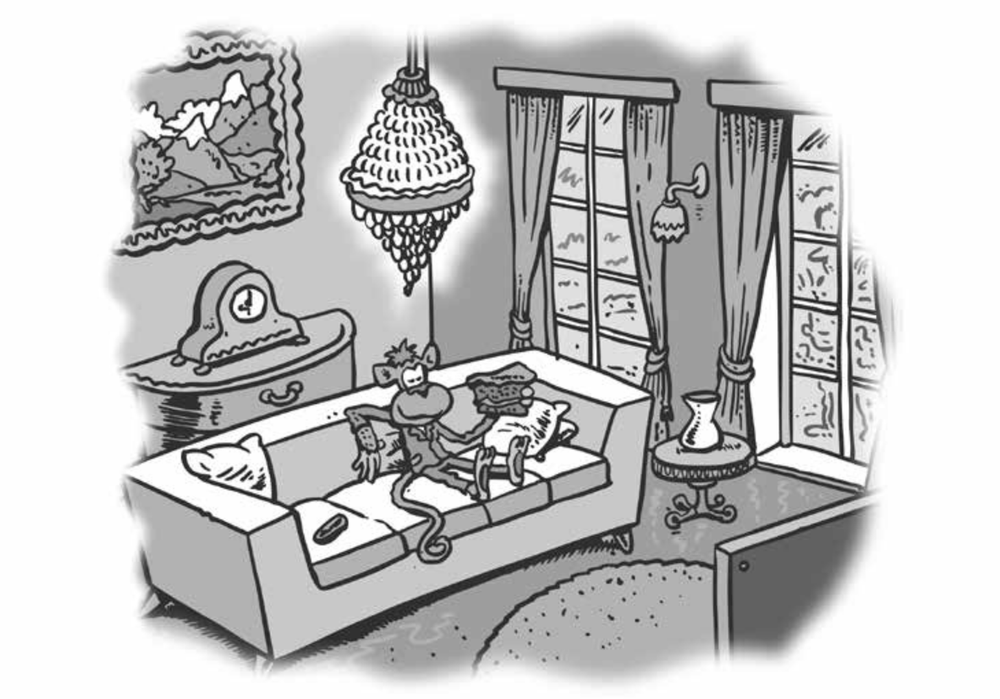

Wow. It really was plush. Chandeliers, marble floor, antique dressers and a luxurious pure white sofa on which sat Thimble, a slice of cake in his hand, watching telly.

‘Thimble!’ cried Dad. ‘Put that down and let us in!’

Thimble waved, let out a stream of monkey chatter, then went back to watching telly.

‘This is a disaster!’ cried Dad. ‘Can you imagine the havoc he’ll create if he’s left alone in there?’

‘Thimble,’ said Mum, ‘be a good monkey and open this window.’

As usual, Thimble was more inclined to listen to Mum. He got off the sofa, came towards us and began examining the window. Then, just as it seemed our wait was over, something distracted his attention and he disappeared from view.

‘Lord give me patience,’ said Dad, which seemed unlikely.

At this point I spotted something. Something very suspicious.

‘What’s that on the sofa?’ I asked.

‘Where?’ asked Mum.

‘Where Thimble was sitting.’.

‘The dark thing?’ asked Mum.

‘Hell’s bells!’ I cried. ‘It’s a poo!’

Next thing I knew, Dad had seized one of the garden chairs.

‘Move aside, Jams,’ he commanded.

‘Dad!’ I cried. ‘You’re not going to…’

Either the chair was very strong, or the window very weak, but all that was left was a metal frame with a few shards of glass hanging. The rest of the glass was spread randomly over the pristine marble floor, while the chair had gone on to demolish a coffee table and the vase which had been on it, spilling dirty green water over a pile of nearby books. Thimble could be heard gibbering frantically in the nearby kitchen, while Mum simply stood with her head in her hands.

‘I never realised you were so strong, Dad,’ I said.

Dad did not reply. He was in a kind of trance, panting heavily. I made my way carefully through the devastation and inspected the dark object on the sofa.

‘Would you believe it?’ I said. ‘It’s a TV remote.’