CHAPTER 2

Football Education, Rutgers Days, Paul Robeson, March Madness, 1917–1920

Walter French was born on July 12, 1899, in Moorestown, NJ, which is located about 15 miles from Philadelphia. He was a direct descendant of one of the town’s earliest settlers. Thomas French, and his wife Jane Aitkins French, arrived in the area from England in 1680. The French family settled in a section of West New Jersey which would become Chester Township. Thomas was one of the original proprietors of the region along with men like Edward Byllynge, Thomas Olive, and William Penn.

Chester was bordered on the north by the Rancocas Creek, to the south by the Pennsauken Creek and to the west by the Delaware River. Thomas French made two land purchases, one in 1684 on the north side of the Rancocas Creek, and one in 1689 along the Pennsauken Creek. French was one of the signers of the “Concessions and Agreements” establishing the town, was very active in community affairs, and was an influential member of the Society of Friends which was the dominant religious denomination in the area at the time.

In 1694, Thomas deeded over 300 acres of his land to his son Thomas French, Jr. on very favorable terms “in consideration of natural affection, goodwill and kindness which he hath and beareth to his beloved son.”1 Thomas French, Jr. built a house on the Camden Pike in 1695 which remained in the French family for 150 years. The original French homestead still stands on what is now called Camden Ave.

Eventually the different communities that made up Chester Township began to break off and set up their own towns, which left the 15 square miles that made up the Moorestown section of Chester on its own.

The French family tree, which developed over the next 200 years before Walter’s birth, was extensive and its influence was felt throughout New Jersey and Pennsylvania. The French family were major landowners and they were active in a wide variety of businesses.

Walter was the fourth child of Walter S. and Belzora Baker French. He had two older brothers, Joseph, born in 1891, and William, born in 1896. One of his siblings, George Baker French, passed away just shy of his third birthday, two years before Walter was born. He also had a younger sister, Esther, who was born in 1901, and a brother, Cooper, born in 1906.

Walter’s father ran a successful construction business in Moorestown and the surrounding communities. The firm’s logo, a piece of iron in the shape of a masonry trowel, can still be found embedded in some of the town’s oldest sidewalks. His firm also worked on projects in the Philadelphia area as well as in Delaware. He was the first contractor in the country to use the advanced road materials being developed by DuPont at that time, which he tested out by resurfacing the roads in New Castle, DE.

As was the case with their ancestors, and the other original founders of Moorestown, the French family were members of the Religious Society of Friends, also known as Quakers. They brought their children up as Quakers and they attended the same meeting that produced famed suffragette Alice Paul. Quakers believe that Jesus’s teachings came in the form of an “inward light.” Quakers would gather together in silence in what were called “Meetings” and in those meetings they could be directly influenced by God.

By the early 20th century the Quakers had given up some of the practices such as their plain dress and speech patterns, that set them apart from the other religious denominations, that by that time had outnumbered them in places like Moorestown. It was around this time that Quakers began to intermarry with those from other faiths. The bedrocks of their beliefs, non-violence and equality between men and women were still stressed and would have been taught to Walter and his siblings.

There were a number of French ancestors however, who despite being Quakers, had embarked on military careers, and their exploits would have undoubtedly been discussed with Walter and his siblings. The two that would likely have captured the imagination of an impressionable youngster were Samuel Gibbs French and James Hansell French.

Samuel Gibbs French was appointed to the United States Military Academy in 1839 and was a classmate of Ulysses S. Grant and like Grant he rose to the rank of General in the U.S. Army. He saw a great deal of action in the Mexican American War which was fought between the years of 1846 and 1848 fighting under General Zachery Taylor in the Battle of Buena Vista in 1847, a battle in which he was wounded. After his military career was over, he was elected to the New Jersey legislature. In 1856 he moved to Mississippi to manage a plantation that he inherited, through marriage. When the Civil War began, he sided with the south and served in the Army of the Confederacy.

James Hansell French received his commission to the United States Military Academy in 1869. Graduating with honors in 1874 he entered the cavalry service as a second lieutenant in the Ninth Regiment and was stationed in Texas. Later he served in Arizona and in 1880 was leading a company in pursuit of a group of Native Americans from the Apache tribe led by the famous warrior chief Victorio. It was during this action in the San Mateo Mountains of New Mexico that he was killed. He was 28 years old.

Walter’s parents too, were not so rigid in their adherence to the principles of their faith as to feel compelled to send their children to the Moorestown Friends School which was established in 1785. Instead they chose to send him to Moorestown High School, the new public high school which was only 10 years old when Walter followed in his older brother William’s footsteps and entered as a freshman in 1914.

While his two older brothers, Joseph and William, were being groomed for the world of business, Walter was free to pursue other interests and for him that meant sports. Although as a boy he showed promise in all sports it was football to which he was most drawn.

Next to the French home on Main Street was a vacant lot owned by Walter’s father. As a boy Walter would invite his friends there to play football. To present himself with the biggest possible challenge and to work on his skills, he would arrange for his team to be manned with at least one fewer player than the opposition, and before he let everyone go home, he would challenge all present to stop him from taking the ball the length of the field.

At Moorestown High School he quickly became a star player in football, baseball, basketball, and track. In addition to competing for his high school team, Walter also joined his older brother William as a member of the Moorestown Collegians. The Collegians were a football team made up of local boys who had “performed in their own little way with school and town teams mingled with those were receiving the benefit of college coaching.”2 The Collegians played annual games against similarly constituted teams from the surrounding towns and teams comprised of soldiers from Camp Dix located a few miles to the north of Moorestown. The tradition continued for six years. The teams coached themselves and devised their own plays. Despite being only a high school freshman, Walter was recognized as one of the stars of the Moorestown team. The team did not lose a game over the six-year period and only gave up one touchdown.

Walter transferred after his junior year to The Pennington Seminary (now known as The Pennington School) located in Pennington, NJ. The Pennington Seminary was founded in 1838 by the Methodist Church. Initially established as a boy-only school, the first women were admitted in 1853, but in 1910 the school reverted to a single-sex institution. Women would not be admitted again until the 1970s.

When Walter arrived at Pennington in the fall of 1917, America was four months into its involvement in World War I and he found that compulsory military training was part of the school’s curriculum. Students were required to wear military uniforms and began each day with reveille and ended each day with taps. They went on long hikes, constructed trenches, drilled, and practiced marksmanship. Although this type of military training was against the Quaker non-violent principles the fact was that a very small percentage of claims for exemption from military service were granted, and most Quaker men, who were drafted, including Walter’s two brothers, served in combat positions in World War I.

All of this seemed to suit him just fine. Pennington Life, which was the yearbook for the class of 1918, listed his activities at the school as “Member of Theta Phi Fraternity; Varsity Football; Varsity Basketball; Varsity Baseball; Track Team; First Sergeant Company B; Dramatic Club; member of the Rifle Team.”3 Walter was getting a well-rounded education with little free time.

He also found a school with a long football tradition. Football had been played at Pennington for 38 years when Walter arrived in 1917, making its program one of the longest running in the nation. Despite all he may have learned at Moorestown High School, or by competing against older boys on the Collegians, he would later describe his experience at Pennington as his first real football education. However, any concern as to how he might fit in at the school, with respect to the sports teams, was quickly dispelled at the first football practice. In short order he was named the starting quarterback and led the team to a 5–1 record outscoring their opponents 194 to 32. Their only loss was to Trenton High School.

At the season’s end, the Newark, New Jersey based Sunday Call newspaper named Walter the second team All-State quarterback. The Trenton Times, however, took issue with the selections made by the Newark Call writing “we cannot even figure a single player from the eleven that is entitled to a place on the All-State Team.”4 The Times then published their own All-State team which listed three players from the Trenton High School team as first team All-State, along with Walter French of Pennington as the first team All-State quarterback.

Walter was also one of the leaders on Pennington’s basketball team, which had a 6–3 record in the 1917–18 season. Two of the losses again were to the Trenton High School team, which finished the season undefeated. Pennington Life summarized the season stating that “our team was a new team, only one man, Captain Blackwell, having played before on our floor. French and Gray, new men, were remarkably strong men and contributed materially to the good standing.”5

In baseball, he was also one of the stars of the team playing an excellent shortstop and he was a key member of the Track team. In its year end summary, Theta Phi Fraternity summarized its contributions to the school’s athletic program and credited French for his work with the football, baseball, basketball, and track teams.

After graduating from Pennington, Walter entered Rutgers University located in New Brunswick, NJ in 1918, as a member of the class of 1922. As with Pennington, Rutgers had a long football tradition. Rutgers played in the first ever college football game when it went up against in-state rival Princeton in 1869. Rutgers also had a successful track record when it came to recruiting athletes from New Jersey. In the years leading up to Walter’s admission to the school, Rutgers sports legends such as Harry Rockafeller, Homer Hazel, and Robert Nash, either came from New Jersey or had attended private school in the state.

He also came to the school at a time of great upheaval for the nation and the school. World War I still would be ongoing for his first 10 weeks at Rutgers. With many students leaving school to serve overseas, the student body at Rutgers during Walter’s freshman school year of 1918–19 had dropped to 286 students down from 513 in the previous year. On October 1, 1918, Rutgers, like most colleges and universities became part of the Student Army Training Corps (SATC), a United States War Department program which made it possible for men to prepare for military service while receiving a college education. Much like his life at Pennington, Walter’s daily routine at Rutgers included military training and drills in addition to his class work. There was some speculation that the rigorous schedule placed on students in the SATC would keep them from athletic competition but one week before the program was formally instituted, Lt. James C. Torpey, the commanding officer of the Rutgers SATC announced that the men would be allowed to play football and other sports if it did not interfere with their military responsibilities.

The second major challenge facing the incoming Freshman class of 1918 was the outbreak of the Spanish flu which took the lives of an estimated 50 million people worldwide. The pandemic hit New Jersey quickly in the fall of 1918. Experts attributed its quick spread to the number of troops that were in close contact with one another at this time. Camp Dix located near Trenton, New Jersey was a perfect example as was Camp Merritt, in Dumont, New Jersey where close to 600 enlisted men died from the flu. Statewide there were 4,010 deaths reported in September of 1918, with 222 caused by influenza, but in just one month the death toll rose to 17,260 deaths in the state with just under 8,500 attributed to the pandemic. At Rutgers 75 students contracted the flu and four died as a result.

The pandemic caused an upheaval with the college football season. Some games were postponed indefinitely, while others were rescheduled or cancelled altogether. On October 9, 1918, the Big Ten Conference announced that it was dropping all their games scheduled for that month. “The season will open on November 2 and close on November 30, the Saturday following Thanksgiving, instead of the preceding Saturday as has been the conference rule”6 read the announcement.

The pandemic affected the Rutgers football schedule in 1918 as well. Games scheduled with schools hit particularly hard, Lafayette, Colgate, Fordham, and West Virginia were all cancelled. The game against Lehigh, on October 26, was moved to New Brunswick after a major flu outbreak hit Bethlehem, PA. In the end the Rutgers Queensmen, as they were known at the time, played a seven-game schedule, which included games against Ursinus, the Pelham Bay Naval Station, Lehigh, the Hoboken Naval Station, Penn State, the Great Lakes Naval Base, and Syracuse.

Despite these challenges Walter found college life very much to his liking. He was very popular with his classmates. He was admitted into the Kappa Sigma fraternity and was even elected president of the Freshman class.

The 1917 football season had been a very successful one for Rutgers. They finished the season with a record of 7–1–1. The only blemishes on their record were a loss to Syracuse and a 7-all tie with West Virginia. Georgia Tech, coached by John Heisman, for whom the Heisman Trophy is named, finished the season with a 9–0 record and was named the national champion. Walter Camp, widely acknowledged as the nation’s foremost expert on college football, who selected the All-American team each year, said that, despite their undefeated season, he could not predict who would have won a head-to-head match between Georgia Tech and Rutgers.

George Foster Sanford was beginning his fifth year as the Rutgers head football coach when Walter French arrived on campus in 1918. After a successful career as a player at Yale, Sanford took the job as head coach at Columbia University, giving up a law career to do so. After leaving Columbia he coached Virginia for one season before leaving coaching to start up an insurance business in Manhattan. Rutgers lured him back into coaching for the 1913 season. He continued to live in Manhattan and work in his business and in turn took no salary from the school.

After what amounted to a breakthrough season for Rutgers in 1917, expectations were high for the 1918 season. Freshman Walter French was facing the daunting task of trying to crack a lineup which was returning almost all of its star players. It was here that Walter would encounter the first in what would be a long line of iconic American figures, that he would play with, for, or against for the next 20 years of his life.

Before becoming a world-renowned singer, stage actor, film star, and social activist, Paul Robeson was an All-American football player at Rutgers, earning those honors in 1917 and 1918, becoming the first Black man to be named All-American twice and joining Fritz Pollard of Brown University as the only Black All-Americans to that point.

Paul Leroy Robeson was born in Princeton, NJ in 1898, the youngest child in a family of seven. His father, Drew, a formerly enslaved man, was a minister in the Presbyterian Church. Paul was only six years old, in January of 1904, when his mother died in a terrible accident. Attempting to lift the stove so she could pull the carpet from beneath it, her dress caught fire when the door to it opened and hot coals spilled out.

In 1907, the Robesons moved from Princeton when Paul’s father switched to the African Methodist Episcopal Zion denomination and took an assignment in Westfield, New Jersey. Since Westfield had too few Black children to support segregated schools, as had been the case in Princeton, Paul attended Westfield’s integrated elementary school. He would later recall “I realize now that my easy movement between the two racial communities was rather exceptional. For one thing, I was the respected preacher’s son, and then too, I was popular with the other boys and girls because of my skill at sports and studies.”7 His skill at sports was considerable, excelling in football, baseball, basketball, and track. While only a junior high school student, he was the starting shortstop on the high school varsity baseball team.

In 1910, his father was reassigned to the A.M.E. Zion Church in Somerville, New Jersey, which was located just a few miles from the Rutgers campus. Again, he was only one of a dozen Black students in a student body of 200. The school’s principal, Dr. Ackerman, was consistently hostile to Paul. When he joined the glee club, the music teacher had to stand up to Ackerman when he objected to her having selected Paul to be a soloist. Besides being a gifted athlete, Paul’s singing voice, which ultimately would be his ticket to stardom later in life, was extraordinary and despite the harsh treatment that he received from the school’s principal, his teachers saw something special in him and provided him with much needed encouragement. In his autobiography Robeson wrote: “Miss Vossler, the music teacher who directed our glee club took a special interest in training my voice. Anna Milner the English teacher, paid close attention to my development as a speaker and debater; and it was she who first introduced me to Shakespeare’s works.”8

When Paul entered Rutgers in the fall of 1915, he became only the third Black student to attend the school in its history which dated back to 1766. Foster Sanford, who had seen Paul play football for Somerville High School, was anxious to have the six-foot-two, 200-pound teenager come out for the football team. The veteran players on the team had different ideas however and rebelled against having a Black player on their team. Some of the white players on the team did everything they could during the pre-season tryouts to get him to quit. During scrimmages they would gang up on him, intentionally miss blocks when he was running with the ball, punch, and elbow him in pileups. It got so bad that Paul told his father that he was planning on quitting. Drew Robeson listened to his son and then looked him in the eye and simply reminded him of where his family’s journey had started. There would be no quitting.

Finally, at one session, after making a tackle, Paul was just about to start getting to his feet when a halfback named Frank Kelly deliberately stomped on his hand as he was walking back to the huddle. On the next play, with Kelly carrying the ball, Robeson shed multiple blockers, wrapped his arms around Kelly and lifted him over his head. Coach Sanford, witnessing the scene and thinking that Kelly might actually be killed, yelled “Robeson! Put him down! You made the team! You’re on the varsity!”9 Paul proceeded to drop Kelly to the field and walked off holding his injured fingers.

“With growing respect, his white teammates gradually accepted him. They nicknamed him ‘Robey’ and even protected him from attempted fouls by opponents who were especially hostile to the first black player they had ever faced.”10

Paul played in four of Rutgers’ eight games in 1915. He was thought to be a very promising player, and Coach Sanford took a special interest in him. He taught Paul the nuances of the game emphasizing the importance of playing a smart game rather than simply an emotional and physical one.

In 1916, when faced with an extremely tough schedule and a team with little experience, Coach Sanford began to build his team around Paul Robeson, making full use of his ability to play several positions. However, it was in 1917 when he burst onto the national scene and became a household name throughout the country.

In the lead up to the showdown with the powerhouse West Virginia team, their coach Earl Neale, appropriately nicknamed “Greasy,” reached out to Coach Sanford suggesting that it might be best for him to bench Paul for this game. Members of the West Virginia team objected to playing against a team with a Black player, and Neale said he was concerned that Robeson might be badly hurt. Coach Sanford assured him that Paul would be able to take care of himself. West Virginia played the game hard but clean and showed their respect for him by lining up to shake his hand at the conclusion of the 7–7 tie.

At the end of the season Robeson was named by every major All-American selector, including Walter Camp, who referred to him as a “veritable superman.” In evaluating Walter Camp’s selections for the 1918 All-American Football Team, the New York Herald stated that “Now to study the team in detail shows this there was never a more serviceable end, both in attack and defense, than Robeson, the two-hundred-pound giant at Rutgers.”11

Expectations were high for the Rutgers football team entering the 1918 season. The team’s first practice was held on September 18. “The Rutgers football squad held its first practice yesterday afternoon under the direction of Foster Sanford with twenty candidates”12 the Trenton Evening Times reported. “Rutgers will have practically a veteran eleven, with the following members of last year’s winning team still eligible: Captain Feitner, tackle; Neuschaefer and Rollins guards; Francke, Conner, Breckley, and Robeson, ends; Gardner and Kelly, halfbacks; and Baker, quarterback.”13

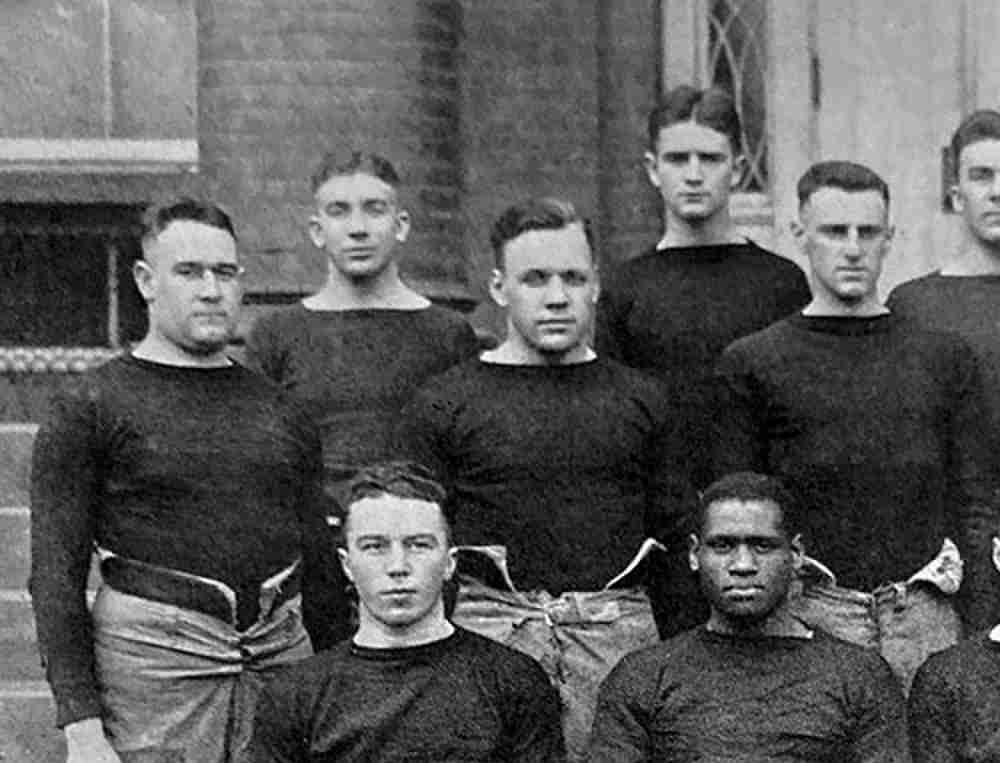

The 1918 Rutgers Football Team. Walter French is standing, second from the left. Paul Robeson is seated, second from left. (1919 Rutgers University Yearbook, courtesy of Rutgers University Library)

Restrictions imposed by the pandemic protocols limited the amount of time that the team was able to practice. This was evident in a sloppy performance against their first opponent Ursinus on September 28, although one could not tell by the game’s final score which was a 66–0 Rutgers victory. Coach Sanford, recovering from the Spanish flu, had to watch the game far from the action. Team trainer Jack “Doc” Besas, put in charge of the team in Sanford’s absence, began making substitutions in the third quarter. Walter French, sent in to relieve Cliff Baker at quarterback, saw his first action as a college football player on that day. The New Brunswick Sunday Times noted that “French showed up as a snappy little quarterback. His passing to the runners was all right. He uncovered plenty of speed when he caught a kick from the tightly pressed invaders from Collegetown.”14

The following week was a different story as Rutgers had all they could handle with the team from the Pelham Bay Naval Station. In this hard-fought game, Rutgers quarterback Cliff Baker suffered a neck injury in the first quarter and Walter was sent in to replace him, and although he could not lead the team to any scores it was noted that “French played a good game for two quarters. The youngster will develop into a great little quarterback. He is rapidly becoming experienced in varsity football and has a great deal of speed.”15 Baker badgered Doc Besas to put him back into the game in the fourth quarter and he scored the game’s only touchdown, running the ball into the end zone in the final minutes of the game.

Next on the schedule was the game against Lehigh, which had to be moved from Bethlehem, PA to New Brunswick due to concerns related to a spike in the Spanish flu in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania. Rutgers rolled to their third straight victory by shutting out Lehigh 39–0. Inserted into the game late in the second quarter, Walter brought the crowd at Neilson Field, including 700 soldiers from Camp Raritan to their feet when he caught a punt and returned it 66 yards, setting up a Rutgers touchdown. Paul Robeson scored two touchdowns in the game as did Frank Kelly. The headline in the New Brunswick Sunday Times blared “Lehigh Failed to Score in Gridiron Battle with Rutgers in which Kelly Starred; Robeson and French Thrill Crowd.” It had to be encouraging for Walter to be included along with the recognized stars of the team in the write ups of the game.

Their next opponent was the team from the Hoboken Naval Transport Service on November 2. Rutgers won easily by a score of 40–0. The star of the game was halfback Turk Gardner who scored four touchdowns. Walter entered the game at quarterback to spell Cliff Baker, who had been limited in practice in the week preceding the game due to an injury. He had success running back kicks, completed a 24-yard pass to Robeson, and capped off the day by scoring his first touchdown as a collegian.

After a lopsided win over Penn State by a score of 26–3 on November 9, expectations were sky high for the Rutgers team who had played five games and had outscored their opponents 178–3, coming into their next game against the Great Lakes Naval Training Center at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. The meeting was only finalized five days earlier, which was November 11, 1918, Armistice Day, which marked the end of World War I.

The Naval team had several All-Americans now stationed there who were part of their team. Their line was anchored by former Notre Dame stars Charlie Bachman, Emmett Keefe, and Jerry Jones. Starting at quarterback and halfback was former Northwestern standout Paddy Driscoll who would later play in the NFL for the Chicago Cardinals and Chicago Bears. Also lining up for Great Lakes Naval was an end from the University of Illinois by the name of George Halas. When the Great War broke out before his senior year, Halas joined the Navy and was stationed at the Great Lakes Center and assigned the task of organizing the football team. Over time he would be known as the founder, owner, and longtime coach of the Chicago Bears and one of the most influential individuals in the history of the National Football League.

Rutgers got off to a good start scoring the game’s first two touchdowns, but the Great Lakes team, which played 30 different players through the course of the game, an unusually high number for that time where teams fielded only one unit which played both offense and defense, soon began to wear them down. When Cliff Baker went down with a hip injury, Walter French was inserted into the game to replace him at quarterback. He gave a good account of himself, completing passes and returning kicks. On two occasions he returned kicks over 50 yards, but it was all to no avail as the final score was a disastrous 54–14 drubbing.

Hopes were high for the last game of the 1918 season against Syracuse at the Polo Grounds in New York on November 30. The game was played in front of a small crowd of just over 4,000, one of whom was Walter Camp, certainly in attendance to put the final touches on his All-American choices. Coach Sanford told the sportswriters that he expected his team to bounce back from the game against the Great Lakes Naval Center. It was not to be however, as Syracuse took advantage of three critical Rutgers mistakes to win the game 21–0. It marked the first time all year that Rutgers failed to score. Two blocked kicks in the first half resulted in the Orangemen’s first two touchdowns. Once again Walter French entered the game when Baker was injured. “Baker, the Rutgers plucky little field general, was again forced to go to the sidelines in the last half on account of injuries” the Central New Jersey Home News reported “French took his place and ran the team exceptionally well.”16 Late in the game however, Walter would contribute to his team’s woes when he fumbled the ball during a kick return and Lou Usher, Syracuse’s consensus All-American guard, scooped up the ball and ran it in for a touchdown, that apart from the extra point, which was executed successfully for the third time, ended the game’s scoring.

The Syracuse game was Paul Robeson’s last football game at Rutgers. Summing up the season in an article he wrote for the Scarlet Letter, the school’s yearbook, teammate Cliff Baker wrote “It is greatly to be regretted that Paul Leroy Robeson should end his football career with two of the worst defeats that Rutgers has ever experienced. ‘Roby’ is recognized by close critics of the game as the greatest and most versatile player of all time.”17 Despite the way his brilliant career ended Paul was named first team All-American once again.

Due to the disruption caused by the Spanish flu and World War I, it was determined that no team would be named National Champion for 1918.

Walter French and Paul Robeson would still be teammates for the remainder of the school year, as both were members of the basketball and baseball teams. At the beginning of the 1918–19 basketball season six lettermen returned to the team, but when the team lost its starting guard from the previous season Robeson later recalled that “Coach Hill, undaunted, looked over the Freshman material for a real fast man and he found him in French.”18 Like with football, however, the star of the Rutgers basketball team was Paul Robeson, in fact there was a sizeable number of observers that felt he was even better at basketball than he was at football.

The 1918–19 basketball season for Rutgers brought out some “fine prospects for another year,” Robeson observed “French should become a valuable man as should the rest of the Freshman combination.”19

In June of 1919, Robeson graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the school and as class valedictorian.

The school year which began in the fall of 1919 saw a return to normal campus life at Rutgers and other schools throughout the country. The signing of the Armistice ending World War I in November of 1918, made the Student Army Training Corps no longer necessary and it was disbanded in December of that year. Also, the Spanish flu pandemic seemed to subside over the summer although it happened without scientists ever really understanding the cause of the deadly disease and there continued to be periodic spikes in cases until 1920. In the end, the only case of the flu on the Rutgers football team was that of Coach Sanford. The football schedule was also more normal. Games against Naval Air Stations were no longer on the schedule and were replaced with the likes of North Carolina, Boston College, and Northwestern.

The season opened on September 27, 1919, as it did the previous year with a matchup with Ursinus at Rutgers’ Neilson Field. As was the case in 1918, Rutgers easily won the game by a score of 34–0. Walter French, now one of the team’s starting halfbacks, scored two touchdowns. The newspaper accounts of the game were critical of the effort put forth by Rutgers however, because it did not inflict a worse beating on the inferior opponent. But unlike the previous year’s game with Ursinus, the 1919 game was only 36 minutes long compared to the more typical 60-minute contest. Playing games where the time of the periods were less than the typical 15 minutes, was not unheard of at that time. The rulebook spelled out the circumstances where a game could be played in less than 60 minutes, and still be considered an official game.

Spalding’s Official Football Guide was the rule book published annually by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). The rules committee was made up of representatives from all the top college programs including such football royalty as Amos Alonzo Stagg from the University of Chicago and Walter Camp from Yale. Stagg had built Chicago into a national power, and introduced a new concept which he referred to as “student service payments” to recruit the best players to the school, which was the precursor to what we today call “athletic scholarships.” Walter Camp was universally considered the nation’s foremost expert on the game.

“Section 1, Rule IV, Length of Game” in the Spalding rule book read “The length of the game shall be 60 minutes, divided into four periods of 15 minutes each, exclusive of time taken out, although it may be of a shorter duration by mutual agreement between representatives of the contesting teams. In case no such agreement has been reached 10 minutes after the time scheduled for beginning the game, the Referee shall order the game to proceed and the full time shall be played.” Section 2 of the same rule added a caveat for darkness. “Whenever the commencement of a game is so late that, in the opinion of the Referee, there is any likelihood of the game being interfered with by darkness, he shall, before play begins, arbitrarily shorten the four periods to such a length as shall insure four equal periods being completed and shall notify both captains of the exact time thus set.” The penalty for failing to abide by the opinion of the referee was forfeiture of the game.

Whether it was the threat of darkness or some other reason, the next week’s much anticipated meeting with North Carolina was played in four 10-minute periods before a crowd of over 3,000 at Rutgers’ Neilson Field. Although North Carolina’s season would ultimately turn out to be a disappointing one, at this early stage of the season they were considered to be tough opponents. Writing in the New Brunswick Sunday Times, sportswriter Harold O’Neill wrote that in North Carolina, Rutgers was facing an “eleven which for years has been ‘ding-donging’ for the championship of the south.”20

Rutgers totally dominated North Carolina, allowing only two first downs in the entire game, and defeating them 19–0. Walter French was far and away the star of the game for the home team, rattling off one long run after another and scoring all three of Rutgers touchdowns.

“This French,” O’Neill reported “who specializes in the open field, is weirdly fast, and possesses a slithering, squirmy quality which makes him almost untacklable.”21

The first quarter of the game was played even, with both teams feeling each other out. Near the end of the period Rutgers put together a sustained drive, highlighted by a brilliant 12-yard run by French which brought the ball deep into North Carolina’s end of the field. Two plays later he ran behind the left tackle for the game’s first score, a nine-yard touchdown run. In the second quarter he pulled off a fake punt and ran the ball back 30 yards and a few plays later plunged into the end zone on a short run. Just before the end of the first half, Walter brought the crowd to its feet with his best play of the game. Taking a pitch from quarterback Cliff Baker at the Rutgers 45–yard line, he ran around the end for 55 yards for his third touchdown.

In the second half of the game North Carolina “resorted to an aerial display and failed again. Not because of wildness of throws or any lack of execution, but because of the agility of Storck, Gardner, Baker, and French at breaking up the forwards when they were not intercepted.”22

The headline in the sports section of the next day’s New Brunswick Sunday Times read “French and Gardner are Dazzling Brilliant in Rutgers 19–0 Victory over University of North Carolina.” The season was off to a great start for Walter French. He was emerging as the team’s star player and had stepped into the gap left by the graduation of Robeson and the other seniors from the 1918 team. He had scored five touchdowns in the first two games of the season. Looking ahead to the remainder of the season Harold O’Neill spoke for everyone at the game when he wrote “Rutgers had a man yesterday that accomplished so much individually and who will continue to do so as the season progresses.”23 However, the season was not going to progress for Walter French as he had hoped.

The next opponent on the schedule was Lehigh. The Rutgers team travelled to Bethlehem, PA for the game on October 11 at Taylor Stadium in front of a crowd of 6,000 fans. The Rutgers team must have been feeling pretty good about their chances. They were coming off an important win over North Carolina and they had beaten Lehigh 39–0 in 1918.

Playing quarterback for Lehigh was Arthur “Buzz” Herrington. Herrington was a mirror image of Walter French. Like Walter he was a sophomore, and the two were similar in terms of their build. Also like Walter, Herrington was fast and tough to stop in the open field.

The game started off as a defensive battle with neither team scoring in the first quarter. About midway through the second quarter, Walter French, who had been playing a solid game to that point, took the ball around the end for a gain of 30 yards. As he was slowed, about to go out of bounds “Buzz” Herrington caught up to him and grabbed him around the shoulders and slammed him to the turf. His head violently hit the ground and a hush came over the crowd. The crowd’s reaction was the type that occurs when it is obvious that a player, friend, or foe, has been badly injured. He lay motionless on the field, out cold. Rutgers put up a good fight but without their star running back they were unable to push the ball into the end zone, despite being in the shadow of the goal posts four times in the second half. Lehigh won the game by a score of 19–0.

Although newspaper accounts differed in their reporting of how long Walter remained unconscious, one thing was for certain, he was still out when he was taken from the field and rushed to the city hospital in Bethlehem. When the team left to return to New Brunswick he remained behind. “Rutgers left behind here tonight one of her sterling players—Walter French,” Harold O’Neill wrote “After being injured in the second quarter, after a great 30-yard run around end, he was taken to the city hospital. It is feared that he sustained a concussion of the brain, though the seriousness of his injuries will not be known until tomorrow.”24 When the Rutgers team returned to New Brunswick, trainer “Doc” Besas and a few other players stayed behind with Walter.

The Trenton Times described the mood on the Rutgers campus after the Lehigh game: “A disconsolate Rutgers eleven was back in college today—disconsolate in a measure over the unexpected trouncing suffered at the hands of Lehigh on Saturday, but the reason for most of the gloom the boys brought back from South Bethlehem was easily traceable to the accident which removed the fleet French from the game and perhaps from the Rutgers lineup for the remainder of the season … it was at first thought that he was suffering from a concussion of the brain. After the Rutgers back regained consciousness, however, it was determined that he was suffering from a sprained neck. Until his accident French had been the Rutgers star and his loss would be a severe blow to the hopes of the local eleven.”25

The reporting on his injury status kept up for weeks, and although the stories differed in a number of details, the reports all insisted that he had some type of neck injury and had not sustained a concussion. The “College Gridiron Gossip” section of the October 14 edition of the Trenton Evening Times reported “Walter French, the Rutgers halfback, who was injured in the Lehigh game and was unconscious for 22 hours, yesterday was found to have suffered only a sprained neck and not as was feared, concussion of the brain. He will be out of the game two weeks.”26 However, in two weeks he was a long way from being back “in the game.” On October 30, the “Gridiron Gossip” reported he had been transferred to a hospital in New York, more specialized in treating his type of injury, still not being described as a concussion.

Although there is a heightened awareness in the game today, “concussions are not a recent discovery in football.”27 Years before Walter’s injury there was “ample evidence that concussions occurred frequently and ample reason to believe that concussions could have long-term pathogenic consequences.”28 Newspapers and medical professionals had been discussing concussions for “more than 20 years as the cause of death and hospitalization.”29 A study done in 1906 found that concussions were happening in “nearly every game.” In 1910, 14 football deaths were recorded with concussions of the brain as the leading cause.

Despite all the awareness of concussions around this time, it was not unusual for medical professionals to arrive at some other diagnosis for an injury that was, in fact, a concussion, or accompanied by a concussion. In Walter’s case he may have had a neck injury, as reported, but it was in addition to a very serious concussion. The length of time he spent unconscious indicates that he had sustained a severe type of traumatic brain injury. After regaining consciousness he would have experienced amnesia, nausea, and a constant ringing in his ears.

The reason that concussions were often not listed as the official injury was not the “result of carelessness” but rather the emerging demand, at this time, for “experimentally supported, evidence-based diagnosis and therapies. Physicians were increasingly expected to rely on technical diagnostics, visualization technologies that would give proof of the presence of a pathology.”30 This was a standard that was very hard to reach when dealing with concussions at that time. “Physicians were all too aware of their inability to produce visual evidence. Injury, they conceded could occur in the brain without visible damage to the head. For injury hidden beneath skin and bone and inches of seemingly unaffected brain tissue, there was no easy means of detection … as there was for fractures of the skull and visible tearing of the brain.”31 The X-ray technology of the time could not detect trauma to brain tissue.

Despite the considerable amount of knowledge the NCAA had regarding the frequency and dangers of concussions it was not until 1933 that the organization published a medical handbook for its member schools. It warned that concussions were being treated too lightly and laid out recommendations to be followed regarding treatment and a timeline to return to play.

The injuries he sustained in the Lehigh game were serious enough to make him miss almost an entire month of the season. Without Walter the team defeated the New York Aggies from the New York School of Applied Agriculture (today SUNY Farmingdale) 14–0 but lost to Syracuse at the Polo Grounds for the second year in a row, this time 14–0.

Walter did not return to action until the third quarter of the game played on November 8, when over 15,000 fans packed Fenway Park in Boston to witness the game between Boston College and Rutgers, almost all of whom were there to support the hometown school. The game looked to be a challenging one for Rutgers, given that BC had beaten perennial eastern power Yale earlier in the season.

Walter French, back with the team was on the bench in the game’s first half. In the first quarter Rutgers blocked a punt and recovered the ball at the Boston College 35-yard line. A few plays later they pushed the ball across the goal line for the game’s first score. Their lead stayed at 6–0 after they missed the extra point. Boston College scored a touchdown in the second quarter and converted the extra point to take the lead.

In his recap of the game, Harold O’Neill described what happened next. “French, Rutgers star halfback was injected into the melee in the third quarter, returning to the game after a four-week absence, and he at once became the star in Rutgers’ firmament. On his first play back, he caught a pass out of the backfield for a twenty-yard gain, and on the very next play he picked up thirty more yards on an end run. Boston had seldom been treated to such spectacular running … All during the second half French made many spectacular end runs” and eventually Rutgers pushed the ball across the goal line, this time making the extra point to give them the 13–7 lead that would hold up as the final score. “All Rutgers men came out of it in good shape,” O’Neill reported, “including French who played the last two periods.”32

The following Saturday Rutgers hosted West Virginia. Led by their superstar back, Ira “Buck” Rodgers, the Mountaineers came into the game hot off an impressive 25–0 win over Princeton. Although it was customary for the quarterback to do most of the passing in those days, it was not unusual for teams, with backfield players with the requisite skills, to design plays that would call for the fullbacks and halfbacks to pass the ball. Rodgers, in addition to being a powerful runner, also had one of the strongest throwing arms in the nation. Playing from the fullback position he threw for 162 yards in the win over Princeton. By the end of that 1919 season he had scored 147 points, from 19 touchdowns and 33 extra points and he was the first consensus All-American in the school’s history. His 313-career point total remained the school record for 60 years. In 1969, during the NCAA 100-year celebration, a team of the century was selected and it included the likes of Bronko Nagurski, Jim Thorpe, Sammy Baugh, Red Grange, and West Virginia’s Buck Rogers.

All of the seats in Neilson Field were full at the start of the game and thousands more stood around the field of play. “On all streets and avenues automobiles were parked, many of the visitors motoring to this center for the engagement.”33 Although the first quarter ended in a scoreless tie, Walter French and Buck Rodgers were both chewing up yards in big chunks for their teams. As was customary at this time both men played both offense and defense, and their tackling abilities, in addition to their work on offense, which were on full display, were responsible for keeping each other from the end zone.

Near the end of the first quarter, West Virginia, starting on their own 20-yard-line, embarked on a successful drive that ended when Rodgers failed to make a first down at the Rutgers 32-yard-line. Rutgers had the ball to start the second quarter and were making some progress moving the ball when the Mountaineers halfback Clay Hite intercepted a pass. But the Rutgers defense held firm and forced a punt. From the Rutgers 45-yard line Walter French took the ball, and as he had been doing throughout the game broke into the clear, only this time he successfully eluded Rodgers and crossed the goal line 55 yards later for the games first score. The hometown crowd went wild.

After more heroics by the teams’ respective stars the first half ended with Rutgers clinging to a 7–0 lead.

In the third quarter the momentum in the game swung, as is often the case, on a turnover. With Rutgers on offense in the shadow of their own goal line a high snap from center rolled into the end zone where Turk Gardner fell on the ball and was immediately downed by one of the Mountaineers for a safety. Taking possession after the safety West Virginia immediately went to the passing game and moved the ball deep into Rutgers territory. After Rodgers completed a pass to Clay Hite at the Rutgers one-yard-line, Rogers ran the ball for a touchdown which, with the extra point, gave West Virginia a 9–7 lead. Later in the same quarter Rodgers hurled a long pass to Bill Neale who had gotten behind the defense. He took the pass in stride and crossed the goal line with the team’s second touchdown of the game. As the third quarter came to an end Rutgers found itself down by a score of 16–7. West Virginia kept up the pressure in the fourth quarter as Rodgers continued to put on an aerial display. He hit Neale for another touchdown in the period and turned the trick again with a touchdown pass to Hite to end the scoring. West Virginia had come away with a convincing 30–7 win.

Despite the outcome of the game, and despite this being only his second game back from a very serious injury, Walter French played one of his best games as a collegian. In addition to his long touchdown run, he had a run of 30 yards and another of 20. He finished the game with 162 yards rushing, on 19 carries, several tackles, and a pass interception. The newspaper report of the game concluded that for Rutgers “French was the most conspicuous man on the offense.”34

The final game of the 1919 season was a match up with Northwestern. In his recap of the game, Harold O’Neill indicated that coming into the game Northwestern was “ruled the favorite before the hostilities began.” However, Northwestern was finishing a dismal season when they traveled to New Jersey to play Rutgers. They were 1–4 in the Big Ten, with their only win coming against Indiana, the final score of which was 3–2. Despite coming into the game with a losing record, a team from the Big Ten would always draw a big crowd when they played on the east coast, and this was no exception as over 15,000 fans turned out for the game.

Northwestern won the toss and was first to go on offense. Walter French intercepted a pass at midfield and ran it back to the Northwestern 25-yard line. A few plays later Bill Gardner, team captain, ran the ball into the end zone and kicked the extra point giving Rutgers a 7–0 lead, only 74 seconds into the game. Gardner added another touchdown in the second quarter giving Rutgers a 14–0 lead.

In the third quarter Walter French “shoved himself into the football limelight,” according to Harold O’Neill, “when on an off tackle play he dashed eighty yards for a touchdown, the most spectacular effort of the matinee.”35 In the third quarter French caught a pass from Cliff Baker and brought the ball to the Northwestern five-yard-line. On the next play he crashed through the line for his second touchdown.

As the clock ran down on the game and the 1919 Rutgers football season, the scoreboard read 28–0 in favor of the home team. The headline in the Sunday Times sports section, ignoring Northwestern’s poor record, read “Rutgers Gives Her Greatest Exhibition of Football Power in Crushing Strong Northwestern Eleven, 28 to 0, Before Assemblage of 15,000; Westerner’s Defense Spreads Before French’s Speed and Gardiner’s Power.”

With the football season at an end, Walter turned his attention to basketball. Coaching Rutgers during Walter’s time there, was Frank Hill. Hill had started coaching at Rutgers in 1915 and held that position until 1943. In a situation that would be unheard of today, Hill also coached Seton Hall’s basketball team from 1911 to 1930, so for the years 1915–30 he was the head basketball coach at both schools. He was also the head basketball coach at St. Benedict’s prep school, in Newark, NJ during some of those years as well.

For scoring coach Hill relied on forwards Leland Taliaferro and Ed Benzoni who were the team’s leading scorers. He also got good offensive production from senior captain Calvin Meury, who played opposite Walter French at guard, and Art Hall a junior who played center. As a basketball player the strength of Walter French’s game were his ball handling skills and his ability to play defense. In a piece in the Central New Jersey Home News, it was observed that “French, the Rutgers basketball guard is a defensive player of the highest caliber. Some days ago, we took occasion to remark that he was not much of a shot, which was not any harsh criticism, for it has been his duty to play defensive ball, and in such work, has made but a few attempts at field goals. On learning through the columns of a newspaper that he was not a field goal shooter, we can imagine French saying to himself ‘I’ll show those newspaper guys where they can get off in the next game.’”36 The next game was against Carnegie Tech and Walter scored five baskets which was second only to Muery’s seven.

Rutgers went on to defeat Carnegie by a score of 46 to 26 and it would be one of 11 wins against four defeats that they would have during the regular season. Other wins came against Pittsburgh, West Virginia, Syracuse, Temple, and Swarthmore. The biggest win in the regular season came against Princeton, which marked not only the first time Rutgers had ever beaten their in-state rival in basketball, but it was also the first time that Rutgers had beaten Princeton in any sport since their win over them in the first college football game ever played in 1869.

As they began to rack up impressive wins against some top opponents, excitement about the team was building on the Rutgers campus. The team was given more support from the student body than any team before had received. Attendance at all home games exceeded previous seasons so much that the seating capacity of the gymnasium needed to be expanded to accommodate all the students who wanted to attend the games.

Although there were teams in the country with a better record than Rutgers, there was no denying that the quality of their schedule was one of the toughest. In the 1919–20 season, Rutgers opponents ended up winning over 70 percent of their games and so at the conclusion of the regular season Rutgers was invited to play in the National Amateur Athletic Union basketball tournament in Atlanta. As the only national postseason tournament, the winner of the AAU tournament was widely acknowledged to be that season’s national champion. Although most of the participants in the tournament were college teams, other high caliber amateur teams were selected in 1920 as had been the case in previous years. Sixteen teams were invited to Atlanta in March to play a single elimination format. To advance to the final a team would have to win games on three consecutive days, with the fourth day for the final game.

Coach Hill was unable to make the trip with the team to Atlanta due to a business commitment and so Doc Besas accompanied them on the trip not as the coach but as more of a chaperone. As if having to play without a coach wasn’t bad enough Rutgers only sent the five starters to Atlanta. If Rutgers was going to win, it would mean that each man on the team would have to play every minute of every game and essentially coach themselves. A few days before the team was to leave for Atlanta the Central New Jersey Home News, published out of New Brunswick, ran a piece under the headline “Here Are Rutgers Players Who Will Contest for National Title” which pictured each of the five players. “On next Monday,” the piece explained, “the Rutgers basketball five, which had a wonderful season, will embark for Atlanta, GA., where, challenging the best amateur clubs and college teams in the country they will contest for the national basketball title. It is the first time that a Rutgers team has ever engaged in such a series and the invitation came as a result of the Scarlet’s feat of winning from such teams as Princeton, Syracuse, Pittsburgh, Swarthmore, West Virginia, and others. The players who will make the trip will be Taliaffero and Benzoni, forwards; Hall, center; Meury and French, guards. During the progress of the championship series, which will consume about a week the collegians will remain in Atlanta, GA.”37

Their first-round opponent was the heavily favored University of Georgia and Rutgers won a close game. On the next two nights Rutgers defeated the University of Utah and the Young Men’s Organization of Detroit to advance to the final. Waiting for them was one of their biggest rivals, NYU. The two teams had met during the regular season with NYU coming away with the victory.

With only one player over 20 years old, the Rutgers team was the youngest in the tournament. Meanwhile, NYU was led by its star player Howard Cann, who was considered one of the best, if not the best, basketball player in the country. He started his college career playing for Dartmouth as a freshman and later transferred to NYU. His career was also interrupted by his two years of military service in World War I. Later he would be named All-American and the Helms Foundation Player of the Year for 1920. In 1968, Cann was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, MA. Rutgers played hard but they were no match for Cann and the more seasoned NYU team and they came out on the losing side by a score of 49–24.

In the early morning hours of the following day, the team boarded a train back to New Brunswick. Despite losing in the final, the effort put forth by the five Rutgers players, without a coach, was the talk of the tournament and a real shot in the arm for the Rutgers basketball program. The closeness of the game with Georgia, for example, was the impetus for discussions exploring scheduling the two teams in the next year’s regular season.

Doc Besas issued a statement to the Atlanta Constitution thanking the people of Atlanta and the Atlanta Athletic Club, who managed the tournament saying, “We certainly do appreciate the treatment we received in your city, and we only desire that, at some point … we will have the opportunity to reciprocate.”

The tournament was a big hit with the people of Atlanta too. There had been some speculation with games being scheduled on four consecutive nights that the city’s interest might wane, however as the Constitution reported that “the fact that Atlanta really and truly enjoyed the tournament is proved conclusively by the fact that the semi-finals and finals were well attended.”

While the team was traveling back to New Brunswick the AAU announced its All-Tournament team. Walter French and Ed Benzoni were selected as first team guard and forward respectively, making Rutgers the only team to place two players on the All-Tournament team.

Before the book was closed on the 1919–20 basketball season the team played one more game against the Rutgers Alumni team, which included their former teammate, Paul Robeson. The 1920 team won by a score of 33–12.

After Coach Hill left Rutgers in 1943, the Central New Jersey Home News, reflecting on his 28-year career, wrote that “Perhaps Hill’s greatest team was in 1919–1920, when Art Hall of Woodridge played at center. Walter French, later a West Point star and outfielder on the Philadelphia Athletics, also played, along with Taliaferro, Meury and Edward Benzoni, undoubtedly the greatest of all Rutgers court aces.” In 2019, the five-man team was inducted into the Rutgers Athletic Hall of Fame.

One notable event took place at the end of the baseball season and the school year in 1920. The University of California baseball team was on a national tour playing 22 games against some of the best teams in the country. It was the first time that a baseball team from a Pacific coast school had traveled east. In addition to playing Rutgers the Golden Bears had games scheduled with Penn State and Carnegie Tech, in the mid-Atlantic swing of their tour, to be followed up with two games against Michigan.

The game with Rutgers was set for June 14 which also happened to be commencement day at the school. Rutgers clung to a two-run lead in the top half of the sixth inning when California took advantage of sudden wildness on the part of Rutgers pitcher Luke Waterfield to plate four runs. They would go on to win 6–4. The newspaper accounts of the game singled out Walter French for his “hitting and daring base running.” He finished the game with two triples and two walks in four plate appearances. He scored three runs, knocked one run in and just for good measure threw in one stolen base.

After the game with California, Walter French, like the other students, was ready to head to his home in Moorestown for the summer. It had been quite a school year. His versatility and success in the school’s three major sports made him the most valuable athlete at the school. Although his football season was limited by his injury in the game against Lehigh, he had scored eight touchdowns in what amounted to, for him, an abbreviated, four- and one-half game campaign. He then helped lead the school’s basketball team to within one win of the national championship and was one of the baseball team’s star players.

The 1919–1920 Rutgers Basketball Team. “Perhaps Hill’s greatest team was in 1919–1920, when Art Hall of Woodridge played at center. Walter French (seated on the right), later a West Point star and outfielder on the Philadelphia Athletics, also played, along with Taliaferro, Meury and Edward Benzoni, undoubtedly the greatest of all Rutgers court aces.” In 2019, the five-man team was inducted into the Rutgers Athletic Hall of Fame. (1920 Rutgers University Yearbook, courtesy of Rutgers University Library)

Before they were dismissed Coach Sanford gathered the players expected to be part of the 1920 Rutgers football team. He told them what he expected of them over the summer and that they were to be back on campus on September 7 to start practice for the new season. Sanford was expecting French to be his bright star in 1920 but it was not to be.