CHAPTER 3

The Big Game: Army vs. Notre Dame, Knute Rockne, and George Gipp, 1920

When the new Superintendent of the United States Military Academy at West Point assumed command in June of 1919, he found a campus in chaos with morale at an all-time low. In response to World War I, and the need to supply officers to the Western Front, Congress had reduced the school’s curriculum from four years to two and in the process eliminated a variety of programs and training. “Not only was the war time disruption a critical problem, but the academy itself, the curriculum, environment, the austere discipline, and the entrenched traditions had caused the school to develop a paternalistic and monastic regimen that caused it to fall behind other institutions of higher learning. In other words, West Point was mired in the past. The disorder caused by the World War and the stagnation needed a major reform, resuscitation, to breathe life and hope back into the academy and resurrect the poor morale of all assigned. This mission would require a special leader, a West Pointer with the vision and clarity to reform, instill a positive spirit and to lead entrenched department heads who were ensconced in their scholarly chairs for decades to a new culture.”1

The choice to replace 70-year-old Samuel Tillman as Superintendent of West Point was 39-year-old General Douglas MacArthur, the youngest general officer in the Army and the most decorated soldier of World War I. He was the second youngest Superintendent ever appointed and several professors and department heads, who made up the all-powerful Academic Board resented having to deal with the younger man as a peer. They also resented his casual manner. Despite being the most decorated soldier to emerge from the war, he was never seen with any of his medals or ribbons. “He dressed in a short overcoat and faded puttees that were lashed to his skinny shanks by curling, war-weary leather straps. He carried a riding crop, and when cadets saluted him, with the usual solemnity of cadets, he replied with a nonchalant elevation of the riding crop to the peak of his shapeless, grommetless cap.”2

He immediately embarked on a mission to reform what he referred to as the “Monastery on the Hudson.” His first action was to change the curriculum back to a four-year program. He sought to have the academy accredited to present a formal Bachelor of Science degree and added courses in history, economics, and government.

MacArthur loved sports, especially football. As a cadet he played on the West Point baseball team but was too skinny for football. So, desperate to be around the sport, he took the position as team manager.

While serving in the Great War, MacArthur observed that many of the American soldiers appeared not to be in the best of shape, so he also instituted a rigorous physical training regimen for the cadets. He even went as far as to require every cadet to participate in sports. His “Every Cadet an Athlete” program is credited with starting the first intramural sports program at West Point and with his arrival intercollegiate sports had greater emphasis than ever before. Under his command the number of varsity sports at West Point doubled in the years immediately following World War I.

The recruitment of athletes to West Point dates back to 1890 when the first Army football team was established. Like their contemporaries at the other schools, the coaches at West Point pushed hard to recruit the best players possible, which included recruiting athletes that had had successful careers and had earned varsity letters at other top colleges.

This was one practice that MacArthur had no intention of reforming. Recruiting players who had established themselves as stars at other schools was not prohibited at the time although most schools frowned upon it. The practice drew the ire of all of Army’s rivals, especially the Naval Academy, which observed a three-year eligibility rule. Things got so tense over the issue that the 1928 and 1929 Army/Navy football games were cancelled due to a “dispute of player eligibility.” Army did not adopt the three-year eligibility rule until the 1930s and a review of the minutes for the Army Athletic Association board reveals that adjustments to it were still being wrestled with as late as 1941.

The poster child for the practice was Elmer Oliphant. Born in Bloomfield, Indiana in 1892, Oliphant moved with his family to Washington, Indiana when he was eight years old, eventually settling in the coal mining town of Linton. In high school he was the star of the football, baseball, basketball, and track teams. He was such a dominant athlete in High School that legends were created around his prowess. One story told was that while playing centerfield on the Linton baseball team, he called time out. He jogged over to the track where a meet was taking place. He proceeded to run in, and win, the 100-yard dash, and then jogged back to the baseball field, once again took up his position, and the game proceeded. The track and football field complex at Linton High School was named Oliphant Field until 1980, in his honor.

Oliphant entered Purdue University in 1910. While at Purdue he lettered in football, basketball, baseball, and track, making him the first athlete at the school to letter in four major sports. He was named first-team All-Big Ten in 1912 and again in 1913. In a game against Rose-Poly in 1912 he scored five touchdowns and kicked 13 extra points to set the school’s single-game scoring record, which still stands.

In 1914 he graduated from Purdue with a degree in Mechanical Engineering, and upon graduation he was accepted as a cadet at West Point, where he again played multiple sports for the next four years, with similar results. He became one of the most decorated athletes in the history of Army sports. He lettered in all the major sports, he also boxed, was a member of the swim team and held the world record for the 220-yard low hurdles. He was named All-American in football in 1915, 1916, and 1917 and he is in the Hall of Fame at both Purdue and West Point. In 1955 he was named to the College Football Hall of Fame. While he was playing football at West Point the team’s record was 21–4–1.

There were other examples of Army’s practice of recruiting players from other schools. Chris Cagle, who had played football for four years at what is today called the University of Louisiana at Lafayette from 1922 to 1925, earning All-American honors in three of those seasons. He attended West Point from 1926 to 1929 serving as team captain during his senior year. For two years Cagle shared the backfield with another All-American named “Lighthorse Harry” Wilson who attended West Point after a three-year stint with Penn State where he earned All-American honors.

The details of Army’s seduction of Walter French are unknown but the news of his departure from Rutgers, which was not announced until a few weeks before the football players were to report for pre-season workouts was met with disbelief and rage at the school. The headlines in the New Brunswick Daily Home News, on the day the story broke, screamed: “West Point’s Round-UP of College Football Players includes Walter French, Rutgers Star Halfback.” Don Storck, the team’s talented end, was also moving to West Point, to make matters worse. The moves were criticized by the New Jersey press covering Rutgers’ football. “In the gush preceding the approaching dawn of another football season, the outlook at Rutgers has been obscured and the large amount of optimism which prevailed at the conclusion of the 1919 season has evaporated due to the usual eleventh-hour circumstances which habitually emerge about this time every year. The main reason for this feeling is due to the departure from Rutgers to West Point of Donald Storck and Walter French two of the ranking members of last season’s somewhat erratic combination”3 the Daily Home News reported.

The news regarding Storck was expected. He had left Rutgers after the 1919 football season, when his appointment to West Point was confirmed. “But the removal of French,” the Daily Home News reported “under circumstances not usually prevalent in these days of sportsmanship came as a shock to the football regime, inasmuch as this individual, the bright scarlet star, was being relied on to be an important cog in this season’s formidable gridiron machine.” The papers covering Rutgers’ football weren’t the only ones weighing in on the subject. Lawrence Perry of the New York Evening Post wrote “there are indications that persons interested in the football prestige of the United States Military Academy are embarked on a recruiting campaign that is far reaching and systematic.” Athletic departments at other schools put out statements condemning Army. Rutgers announced that they would not play Army again in any sport until the practice of recruiting players from other schools was stopped. (With respect to football it was not that big a threat as Army and Rutgers hadn’t met since 1914 and they did not play each other again until 1965.)

For the Rutgers faithful, Army became the bad guys and Navy the good guys. The sports pages of the newspapers in New Jersey were making the case that grabbing Walter French and Don Storck was the only way that Army could compete with Navy, which contrary to Army was building their team the “right” way. “New men and good ones will be needed in the molding of the 1920 machine, for several veterans have been lost to the team for one reason or another. Storck and French are at West Point along with a number of other college stars marshalled together in a daring effort to overthrow the Middies in late November.”4 This, of course overlooked the fact that from 1913 to 1916 Army had defeated Navy each year by a combined score of 71–16. World War I cancelled the games in 1917 and 1918, and Navy won the 1919 game by a score of 7–0.

Looking for someone to blame, the Rutgers community, including the local media, at first suspected that those officers running Rutgers ROTC program may have had a hand in convincing Walter to make the jump to West Point, but that theory was quickly debunked, “it is understood that the military authorities at Rutgers had nothing whatever to do with the transfer of either Storck or French to West Point. The Army captain who succeeded in interesting both these men in military life, was not in any way connected with Rutgers.”5 While speculation as to how this could have happened was running rampant, the explanation was no more complicated than the fact that the West Point coaches and athletic department had their eye on Walter and reached out to him when he was there to play baseball for Rutgers against Army in the spring of 1920. Much in the same way as would happen today, before returning to Rutgers Walter was taken to New York City and wined and dined by an Army captain to influence him to join the Academy.

As the 1920 season neared however, the New Jersey newspapers would not let go of the French transfer story, even speculating that he had somehow been coerced into jumping teams. They even went so far as to suggest that he was not happy with the move, and they floated conspiracy theories that claimed that he was being held at West Point against his will. “On reaching West Point after accepting the appointment under influence, he made an effort to resign, but the authorities refused to accept it and put him in the Army hospital for a time.”6 Even weirder was the story of the wife of a mystery captain who reportedly went to his College Ave. fraternity house in New Brunswick and packed up his belongings and took them to West Point.

It all seemed farfetched because as we shall see going forward the military life seemed to suit Walter French very well. It is always possible that he gave out mixed signals to his former coaches and teammates in an effort to let them down easily. It is also possible that he did have second thoughts after arriving at the school and if so, he wouldn’t be the first cadet to experience that feeling, but to suggest that there was some confrontation that ended up with him being admitted to the hospital simply strains credulity.

There is one oddity regarding his appointment to West Point in 1920 that does call into question the extent that Army went through to bring Walter French to the academy.

In 1843, with the support of then President John Tyler, the Congress increased the class size at West Point to 223 which just so happened to match the size of the U.S. House of Representatives at that time. Tyler assigned the job of selecting the new cadets to his Secretary of War, who in turn asked the congressmen for nominations. This was the start of the system that exists today which requires that a service academy candidate, except for those to the Coast Guard, be recommended by a member of Congress. Typically, that recommendation would come from a member of the Congressional delegation from the candidate’s home state. However, Walter’s recommendation did not come from any of New Jersey’s members of Congress. Walter’s recommendation came from Congressman Christopher “Christy” Sullivan, who represented New York’s 13th Congressional District, which was made up primarily of Manhattan.

After serving four terms as a New York State Senator, Christy Sullivan ran for and was elected to Congress in 1918 and he would remain in that position until 1941. In the 24 years he served in Congress, Sullivan never made one speech. His attendance record was abysmal, and he was more likely to be spotted at any number of Maryland’s horseracing tracks than in the halls of Congress. His power came from his position as one of the last bosses of Tammany Hall. Tammany’s political power was derived from favoritism and patronage and if Superintendent MacArthur was inclined to put the arm on a congressman for a favor, Christy would be a likely target. Was it that all of the New Jersey members of Congress had already made their recommendations on behalf of other constituents that required the congressman from New York City to step in, or is it possible that those congressmen from New Jersey were reluctant to incur the wrath of the boosters of their state university’s football program?

It is more likely that, with MacArthur’s emphasis on intercollegiate athletics, Walter was offered admittance to the Academy, and once he accepted, the nomination process was put in motion with Sullivan on his behalf.

In any event, the recommendation of a New York congressman for a candidate from New Jersey must have raised some eyebrows and fed into the hysteria at Rutgers over the departure of its star player.

It might have been different if Walter had arrived at the Academy prior to MacArthur’s arrival, but he had been on the job for over a year, and most of his reforms were in place. His reforms were enormously popular among the cadets with the exception of his restrictions on hazing but given that the victims of hazing were the fourth-year men or plebes, as they were called, Walter could not have had a problem with that change. Some of the other reforms instituted under his superintendentship meant that “Cadets could afford ice cream now, because one of MacArthur’s first innovations had been to allow each of them five dollars a month spending money. On weekends they were now granted six-hour passes and, in the summer months, two-day leaves. They could travel as far as New York City on their own. During the football season they were allowed to follow their team Black Knights to Harvard, Yale, and Notre Dame. Their mail was no longer censored.”7

And then there was MacArthur’s love of sports, especially baseball and football. He showed up at almost every practice for both sports and was even known to give the players a pointer or two and throughout his tenure had been known to let transgressions slide when a key athlete was involved.

But even though he never played the game while at West Point, it was football for which he had the most passion because football he believed made men better soldiers. “Over there,” he said to a colleague, “I became convinced that the men who had taken part in organized sports made the best soldiers. They were the most dependable, hardy, courageous officers I had. Men who had contended physically against other human beings under rules of a game were the readiest to accept and enforce discipline. They were outstanding. I propose, therefore, to obtain for the Academy athletes, those who have had bodily contact, especially football.”8 He encouraged congressmen like Christy Sullivan to appoint gifted athletes to West Point and gave special privileges to members of the football team in the fall. He also proposed the construction of a 50,000-seat stadium for football.

The fact of the matter was that Walter French could not have entered West Point at a better time, and any reticence he may have felt on his first day, was no more or less than what any fourth-year man from a small town in New Jersey would have felt. Which is not to say that he would not have found the Academy life challenging even with the MacArthur reforms in place. The West Point curriculum for fourth year men in 1920 included Mathematics, English, French, Surveying, and Gymnastics. In addition, cadets also had to deal with room and uniform inspections and the obsession with physical fitness and punctuality.

Coaching the Army football team when Walter arrived at his first practice was Charlie Daly. Born in Roxbury, Massachusetts in 1880, as a player Daly was a first team All-American four times in his five seasons as a college quarterback. He played for Harvard from 1898 to 1900 and was first team All-American all three of his years playing for Harvard. Then, in the Army tradition he received an appointment to West Point from Massachusetts Congressman John H. Fitzgerald and played quarterback for Army in 1901 and 1902, earning first team All-American in 1901 and third team honors in 1902. After working in business and serving in the military for a few years he was named the assistant football coach at Army in 1907. He later served as the Fire Commissioner for the city of Boston from 1910 to 1912 until he was given the opportunity to be the head football coach at West Point. He served as the coach from 1913 to 1916 compiling a record of 31–4–1. He left the post to serve in the military in 1917 and 1918 during World War I and returned to his coaching position in 1919 and compiled a record of 6–3 in that season.

West Point’s practice of recruiting players who had played for years in other programs really did make it hard for them to schedule games with the top schools. The schedule Walter had to face in 1920 had only two top caliber opponents, Notre Dame and Navy. The rest of the schedule included Union, Middlebury, Springfield College, Tufts, Lebanon Valley, and Bowdoin. Had he stayed at Rutgers, by contrast, he would have gone up against the likes of Maryland, Nebraska, Virginia Tech, West Virginia, and Cornell.

Army’s first opponent in 1920 was Union College. Over, almost before it started, Army dispatched with the Dutchmen without breaking a sweat, by a score of 35–0. They followed that up with another easy win against Middlebury, by a score of 26–7. Coach Daly went easy on them in practice leading up to their third game of the season against Springfield College. The Springfield game, like the ones before it, was played at West Point. Newspaper accounts after the first two games of the season singled out French’s play as being key to the team’s early success writing that “The work of French, Army’s speedy back is pleasing his mentors. The former Rutgers star is one of the shiftiest backs in the game and bound to be heard of frequently during the season.”9

Coach Daly was so confident that his team could easily handle their next opponent Tufts, that he sent the starting 11 to the Princeton–Navy game to scout out the midshipmen. The entire West Point varsity team went to Princeton to see the Tigers take on Navy, leaving the second team behind to defeat Tufts 28–6. The Cadets made the trip in autos. During the return trip French, Don Storck and the others stopped at the Hotel Pines in New Brunswick for a bite to eat. While passing George and Albany Streets, French inquired of the traffic officer on duty there as to the outcome of the Rutgers–Virginia game. Still smarting from the Army’s recruitment of French, the New Brunswick News reported that “if that same French had been in the Rutgers lineup Saturday, they would be celebrating a victory instead of bemoaning a defeat. For the speed that only French can supply was all that was needed to put the local collegians on the winning side. The Rutgers backfield has no fast back to cover long distances at a clip such as French used to do.”10

So, the stage was set for one of the biggest college football games to be played at that juncture of the season and the seventh meeting between Army and Notre Dame on October 29, 1920. Prior to the construction of Michie Stadium in 1924, Army played their home games on a 40-acre piece of land on the campus that was known as “The Plain.” The Plain was used primarily as a marching ground and the site for the summer camp outs for the cadets. Temporary stands were set up to seat about 10,000 fans before each game.

Both teams came into the game undefeated although no one could argue that Notre Dame with opponents like Nebraska, Syracuse, and Boston College had played the tougher schedule to that point of the season and thus was a heavy favorite.

Although it is hard to picture today, historically the rivalry between the two teams was fierce. Legendary Notre Dame coach Frank Leahy later said of the rivalry that “for 34 years the Army game was the high-water mark on the Notre Dame schedule.” Adam Walsh, a member of the 1924 national champion Notre Dame team and later head coach at Bowdoin College described the battles between the two teams this way: “If we weighed 180 pounds, we’d always hit with 200 pounds of power against Army and the Cadets would meet us in the same manner.” Walter’s teammate on the Army Baseball team, Earl “Red” Blaik, who later became the Athletic Director at Army speaking in 1948 described the Army-Notre Dame rivalry as “one of the greatest in all of sports.”

Writing in his syndicated column in 1943, Grantland Rice recalled that “the Army-Notre Dame contest was always Knute Rockne’s favorite game.” “It is usually the toughest game we play,” Rockne told Rice, “But it is the type of game I like to play, hard and tough, but clean. Always full of action. Always full of color. We’ve won some close ones that we might have just as well lost. I know that, but it was the game that helped lift Notre Dame in football and it was the game that gave us our first and biggest eastern break. Even when we had the better team, I was never sure of this Army contest for those Cadets always gave us at least 100 percent of all they had and often just a little more. I can’t remember an Army-Notre Dame game that was not interesting.”11

The rivalry between Notre Dame and Army began with the first game played between the two teams in 1913. Leading into the 1913 season the Spalding Record Book had Notre Dame rated on a par with the reigning Big-10 champion Wisconsin and so the feeling was that many of the midwestern coaches were reluctant to play Notre Dame, afraid that their reputations would have little to gain from a victory and a lot to lose with a defeat. Prejudice against the Catholic institution also contributed to this reluctance. This required that Notre Dame be open to the idea of traveling far to fill out its schedule for 1913 if they wanted to break into the national limelight.

In the summer of 1912, Bill Cotter who was the student manager of the Notre Dame team and Knute Rockne, at that time the team’s top end and one of its star players, were working together as lifeguards at a resort in Ohio named Cedar Point, which was located on the shores of Lake Erie. It was there that they first discussed the idea of scheduling games with the cadets. What better way to enhance the school’s reputation than playing an east coast power like Army? The following January the first communication between the two schools took place regarding, not football, but baseball. An agreement was reached which would have the Notre Dame baseball team play Army during a swing through the eastern part of the country in May. On May 24, 1913, Notre Dame defeated Army 3–0, in the first ever sports contest between Army and Notre Dame.

At about this time Army found itself in a similar predicament with respect to their football schedule for 1913. The Cadet football manager, a student named Harold Loomis, was informed that the 1912 game between Army and Yale would be the last of that series. Both teams apparently agreed with the decision. Earnest “Pot” Graves who was the Army coach and Lt. Dan Sultan, the Army Athletic Association representative and the coaches from Yale felt that the game took too much out of their players each year. So, Loomis found himself in a bind as he tried to fill an open spot in the Army schedule in the late October early November time frame. He first wrote to all the eastern schools but each one replied that their schedules were all full. Desperate he started writing to every school in the country but as of spring 1913 he still had no game scheduled. Finally he got a response from newly hired Notre Dame coach Jesse Harper. Harper played under Amos Alonzo Stagg at the University of Chicago from 1902 to 1906. He became the coach at Alma College in Michigan and later coached Wabash before coming to Notre Dame in 1913.

Harper was not ready to commit to the game but wanted more information including how much money could be guaranteed to the Ramblers for making the trip (Notre Dame would not officially adopt the Fighting Irish nickname until 1927). If those types of requests were not unheard of in those days, it was, at least, an out of the ordinary request in Army’s view. Well-heeled schools like Yale always paid their own way, but Notre Dame, in 1913, was not well heeled.

Army initially offered Notre Dame $600 to cover their expenses but Harper replied that to bring his full team would cost $1,000 and he couldn’t justify bringing them for a penny less. Eventually Army agreed to meet Harper’s demand and the game was set and the teams squared off on November 1, 1913. Notre Dame won the game by a score of 35–14 and they would finish Coach Harper’s first season undefeated. In addition to being the start of a great rivalry, however, the game was destined to be remembered as one of the turning points in the evolution of the game of football.

In 1906 John Heisman convinced the football rules committee to legalize the forward pass. He believed, correctly, that opening up the game would save it from dangerous tactics like the Flying Wedge and plays of similar mayhem. Heisman had the backing of then President Theodore Roosevelt who had expressed his concern about the number of fatalities that occurred in the previous two seasons. In addition to the legalization of the forward pass, the rules committee, in a move to open up the game, also approved the creation of the neutral zone along the line of scrimmage between the offensive and defensive lines and the doubling of the distance required for the offense to obtain a new set of downs to 10 yards.

Initially the rules regarding the forward pass had several restrictions which kept it from becoming popular with the top teams in the country. These included limiting pass plays to 20 yards, the assessment of a 15-yard penalty for an incomplete pass and a requirement that the ball go over to the defense if an untouched pass fell to the ground.

The restrictive rules did not stop the team from the Pennsylvania Carlisle Indian Industrial School from being the first team to widely use the forward pass, along with a few other trick plays in 1907. Coached by “Pop” Warner and led on the field by Jim Thorpe, Carlisle used a wide-open style of play to compensate for a lack of size and finished the season with a record of 10–1 and outscoring their opponents by 200 points.

Finally in 1912 the NCAA Rules Committee did away with many of the restrictions that had been imposed on the passing game. They also approved new specifications for the football making it longer, slimmer, and much easier to throw.

However, most of the nation’s coaches still considered the play a risky gimmick and the forward pass was not widely used until the Notre Dame vs. Army game in 1913.

Also joining Bill Cotter and Knute Rockne on the staff of that Ohio resort was Notre Dame quarterback Gus Dorias and he and Rockne spent much of their free time working on the passing game, and on November 1, 1913, they rolled it out against a shocked Army team. What Rockne and Dorias worked on was a departure from the normal way the passing game was executed in those days. Rather than the receiver running out for a pass and stopping in an open spot as was customary at the time, the two teammates worked on pass patterns which called upon the quarterback to deliver the ball not to where the receiver settled down in the coverage, but to anticipate where the receiver was going to be and complete the pass while the receiver was on the run. Dorias completed 14 of 17 passes for 243 yards, mostly to Rockne. With its size advantage neutralized, Army was helpless to stop the Notre Dame attack. The game put Notre Dame on the national football map to stay, and established the forward pass as a weapon that every team would have to have as part of their playbook. One newspaper account summed up the game this way “the westerners played the fastest game of football seen on the gridiron in years. Their open field running, brilliant forward passing, and sure handling of the ball was pretty to watch but was a source of much discomfort for the cadets, who seemingly never had a chance.”12 The origin of the way football is played in the modern era can be traced to this game and it also opened the door for players with the size and skill set of Walter French to find a place in it.

By the time the 1920 Army vs. Notre Dame game came around, the Ramblers had won four of the six previous contests, winning in 1915, 1917, and 1919 in addition to the win in the inaugural 1913 game. Army was victorious in 1914 and 1916. There was no game in 1918. Knute Rockne had also succeeded his mentor Jesse Harper as the head coach of Notre Dame when he retired after the 1917 season. After going 3–1–2 in 1918, the Ramblers finished the 1919 season with a perfect 9–0 record.

At the heart of the Notre Dame team at that time was George Gipp. Gipp, the son of a minister, was born in 1895 in the town of Laurium located on Michigan’s upper peninsula. After dropping out of high school, according to Gipp biographer George Gekas he “spent much time at Jimmy O’Brien’s Pool Room, which was three blocks from his house on Hecla Street in Laurium … For money Gipp would drive cabs on the weekends, ferry copper miners to and from the bars and local houses of prostitution.”13 He also played semi-professional baseball at this time. A friend by the name of Wilbur “Dolly” Gray, who had been an outstanding catcher for Notre Dame’s baseball team convinced Gipp and Coach Harper to have him enroll at the school through a baseball scholarship. Because he had not completed high school he was admitted as a conditional Freshman, with the plan being for him to make up his credits during summer school. In his book Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football, author Murray Sperber wrote that “The twenty-one-year-old Gipp arrived at Notre Dame in September of 1916 and discovered that his job as a waiter in Brownson Hall covered only his room and board bills; he would have to pay out-of-pocket for his books, supplies, fees, and other expenses. Gipp immediately embarked on what fellow students called ‘his own private job plan’—earning money by playing pool and cards in downtown South Bend. He was so skillful a gambler that he quit his job waiting tables after one semester and eventually moved out of the dormitories, living the rest of his Notre Dame years in the luxurious Oliver Hotel in South Bend, home to various affluent citizens, commercial travelers, and high-stakes billiard, pool, and poker games.”14

Although Gipp went to Notre Dame to play baseball he also played on the Freshman football team in 1916. It was as a member of that team that his football potential first came to Rockne’s attention. In a game on October 16, 1916, against Western State Normal of Michigan, Gipp kicked a 62-yard field goal. Soon he was playing multiple positions on the team and regularly going up against the varsity team in practice. He joined the varsity team for good in 1917 and led the team in rushing, passing, and kicking for the next three years. Legendary sportswriter Ring Lardner reflecting on Gipp’s years at Notre Dame stated that “Notre Dame had one formation and one signal … have teams line up, pass the ball to Gipp, and let him use his own judgement.”15

While his football, poker, and pool skills were first rate, Gipp’s academic performance left a lot to be desired. He rarely went to class and never completed many of his courses. On March 8, 1920, Notre Dame attempted to expel him but “immediately there were at least six major universities in contact with George trying to lure him to their schools in spite of his scholastic predicaments”16 including the athletic department at West Point, no doubt with the encouragement of Superintendent Douglas MacArthur. A telegram was sent to Gipp from Captain Philip Hayes, from the Army Athletic Association on July 27, 1920, telling him that “You have been recommended for appointment to the United States Military Academy … please write me collect whether or not you will consider acceptance.”17 And so it was that his expulsion was brief, all was forgiven, and a few weeks later he was back living at the Oliver Hotel, playing cards and semi-pro baseball.

As the 1920 season began to unfold, Walter French was emerging as Army’s star player. His break away running style was reminiscent of the style of play that made Elmer Oliphant a star, and Army coach Charley Daly found in French a more than suitable replacement for Oliphant.

At the time Army played a single wingback system, which usually called for big bruising style runner as opposed to French’s game which was based on his ability, not to run over defenders but to elude them. The single wing, however, also presented a player with Walter’s skills with the ability to disguise whether he intended to run or pass when he had the ball, at which he was equally good. Writing in The Big Game: Army vs. Notre Dame 1913–1947, Jim Beach and Daniel Moore described French’s play this way “He slithered through slight openings and was gone before the defense knew what had happened. He was small of physique and shifty with the agility usually characteristic of a scat-back. He was also tough and could stand up under the battering a little man has to take in football.”

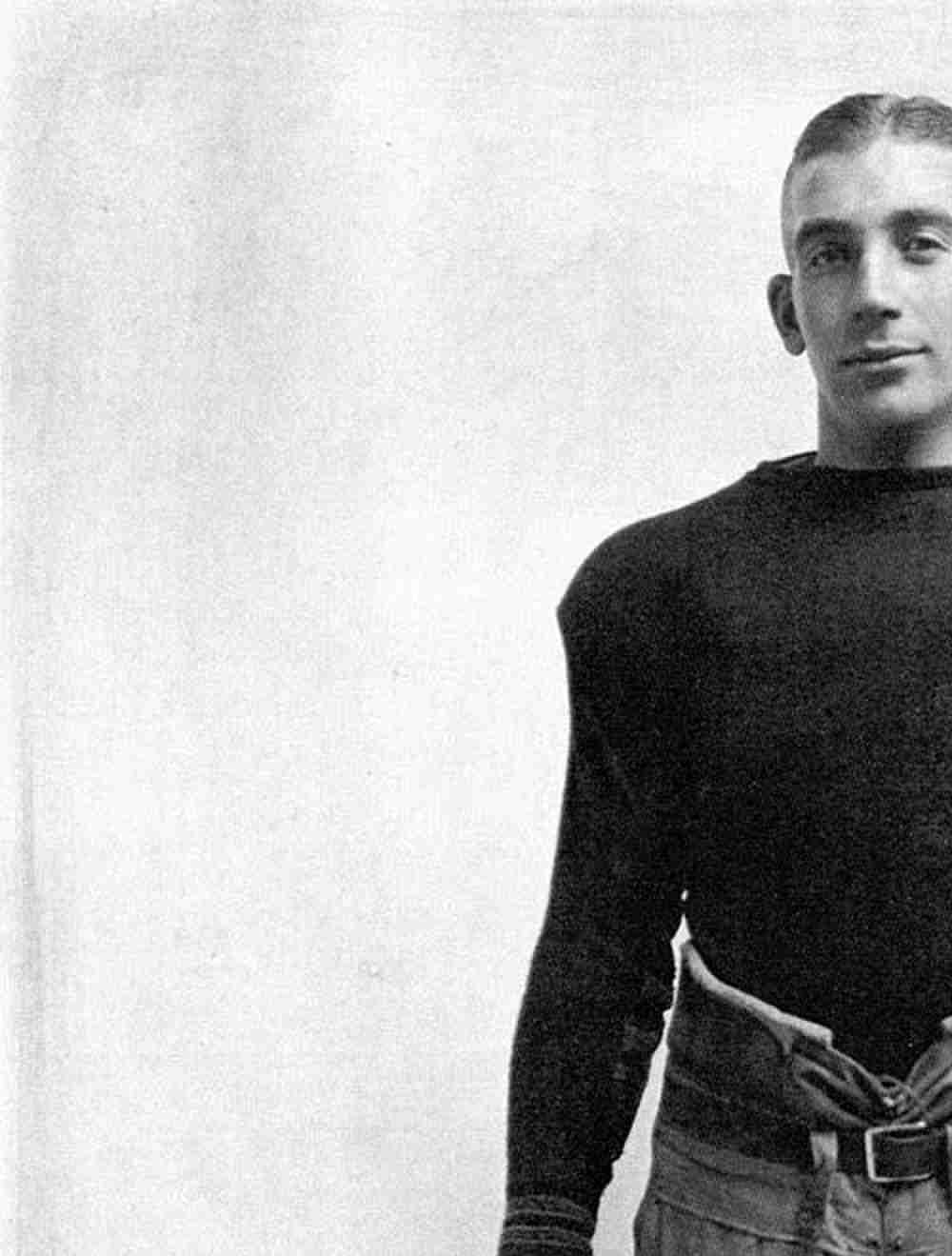

Walter French was the star of Army’s football team and named All-American in 1920. “He slithered through slight openings and was gone before the defense knew what had happened. He was small of physique and shifty with the agility usually characteristic of a scat-back. He was also tough and could stand up under the battering a little man has to take in football.” (Courtesy of French Family)

So, the stage was set for one of the most anticipated showdowns of the college football season. In their advance stories, the sportswriters were playing up the head-to-head meeting between George Gipp and Walter French.18

The weather in the West Point area in the week before the game was dreadful. The New York Times reported that the Cadets “drilled in the rain” in the days leading up to the game.

After a 22-hour train ride, the Notre Dame team comprised of 23 players arrived on the West Point campus in the late morning of October 29, 1920, in what the New York Times described as a “driving rainstorm.” Experts were predicting that the field would be sloppy with a slower than normal track. After arriving on campus, the Notre Dame team held a light workout in the rain.

It was not uncommon in those days for teams to wager on their own games, with each team collecting cash from the players and throwing it into a winner take all pot. Gipp’s best friend on the team and fellow Upper Michigander, Hunk Anderson collected the Notre Dame share and met with the Army team manager to arrange for a wager to be placed on the game. Each team put in around $2,000 into the pot for a purse that would equal about $55,000 in today’s currency.

The temporary stands on The Plains were filled to their 10,000-seat capacity, with a sizeable contingent of Notre Dame fans on hand. Also in attendance were all the top sportswriters of the day including Grantland Rice of the Herald Tribune and Ring Lardner of the Chicago Tribune. Years later, Rice would recall that “Ring Lardner, a keen Notre Dame and Midwestern rooter, went with me on that trip to the Point in the fall of 1920. We ran into John J. McEwen, the big Army assistant coach. John J. was loaded with confidence. One of Army’s all-time centers, John coached the Cadet line. Army’s strong squad was headed by the flying Walter French, who earned his spurs—and an appointment to West Point at Rutgers.”19

The weather had cleared, and the windy conditions helped to dry out the field, so it was a little faster than what had been anticipated earlier in the week but was still soggy. Kickoff was scheduled for 2:30pm and the referees concerned that darkness might fall before the conclusion of the game used their authority to declare that the time of the periods for this game would be 12 minutes rather than the more typical 15-minute quarters. So, one of the greatest college football games to that point in time would only be 48 minutes long.

At the conclusion of the warm-ups and just before the start of the game Gipp walked out to the 50-yard line with four footballs. Without giving any indication that what he was about to attempt was anything special or out of the ordinary, he proceeded to dropkick two balls through the uprights in one direction and then turned around and kicked the other two balls through the goal posts at the other end of the field.

Notre Dame received the opening kickoff and immediately started moving the ball downfield, moving into Army territory in just four plays. On the next play Notre Dame center Ojay Larson snapped the ball from Army’s 38-yard line directly to fullback Chet Wynne. Wynne, known as the Kansas Cyclone, ran into the line for three yards, where he was met by three Army tacklers, and fumbled. George Gipp and Army’s Don Storck both went for the loose ball and a struggle ensued. After he arrived on the scene the referee pointed to the Notre Dame end of the field. Storck had recovered for Army.

Glenn “Willie” Willhide was Army’s quarterback and on Army’s very first offensive play he handed the ball to running back Charlie Lawrence who slammed into the line and promptly fumbled the ball, but he was able to recover his own fumble and Army retained possession. On the next play Willhide handed the ball to Walter French who ran the ball into the line behind the right tackle. Once free of the initial Notre Dame defenders he eluded Chet Wynne and burst into the open field with only the safety between himself and the goal line. The safety made a touchdown saving, shoestring tackle pulling down French but not before he had advanced the ball 40 yards to the Notre Dame 23 yard-line. On the next play Willhide went back to Charlie Lawrence who plowed through the left side of the line, and after being initially stopped at the five-yard-line, powered his way into the end zone. After Fritz Breidster’s extra point kick was good, Army took the early lead 7–0.

The ensuing kickoff was a low, bouncing ball that Gipp fielded at his own 10-yard-line and ran back 28 yards to the Notre Dame 38-yard line. Chet Wynne took the ball on the next play up the middle to his own 44-yard line. Gipp carried the ball on the next play to midfield where he was tackled by a host of Army defenders and buried in a big pile up. Gipp, feeling that the Army defenders had gotten away with unnecessary roughness, jumped up and started to confront the entire Army team. Gipp ripped off his helmet and a fight broke out between the two teams. Gipp began mixing it up with two of the Cadets until the officials were able to restore order and march off a penalty against Notre Dame, which wiped out their gains of the last few plays.

Furious with what he felt was an unfair call, on the next play Gipp took the ball around the right end and dashed through the open field. Walter French, playing the safety position, moved up to the Army 40-yard-line and made a flying tackle to bring Gipp down. After a few short gains the Notre Dame quarterback fumbled the ball, but this time Gipp was there to recover it and maintain possession for Notre Dame. Gipp then completed two forward passes, the second to end Roger Kiley who brought the ball to the Army five-yard-line. From there, halfback Johnny Mohardt finished the drive when he plunged into the end zone. Gipp kicked the extra point and the game was tied 7–7 as the first quarter came to an end.

On their first possession of the second quarter Army went three and out and were forced to punt from their own five-yard-line. Walter French was standing just in front of the back line of the end zone, with very little room to maneuver, set to punt the ball. In what must have been one of the best punts of his life he sent the ball some 60 yards in the air as it crossed the 50-yard line on the fly and forced Gipp to retreat to his own 35-yard line to retrieve the ball and start to head up field. Gipp, taking advantage of Army defenders who had overrun the play, was able to return the ball into Army territory before being tackled from behind as he attempted to reverse field. After a couple of running plays, Gipp threw a pass to Roger Kiley, who had made it seem like his role on the play was simply that of a blocker and then broke wide open, catching Gipp’s pass and running into the end zone. The extra point gave Notre Dame a 14–7 lead.

After the teams exchanged punts on the next few possessions Notre Dame found itself with the ball on their own 25-yard line. An errant snap from center got away from Chet Wynne and he was forced to fall on the ball at his own 10-yard-line, requiring Gipp to punt the ball from behind his own goal line. The punt, a low driving kick that cut through the wind sailed over the head of Walter French, who was back to receive the punt. Walter quickly ran back and picked up the ball at his own 40-yard-line and began to run diagonally to the sideline. Suddenly he changed direction, running past would-be tacklers. With the help of a few blocks from his Army teammates, he continued to weave his way through a wave of Notre Dame defenders. At some point he outran his own blockers and with one last change of direction he crossed the goal line for a touchdown which, after the extra point, tied the game at 14–14.

As the first half was coming to an end Johnny Mohardt took the kickoff and was swarmed under by an Army team now pumped-up by Walter’s heroics. After going three and out, George Gipp was forced to punt from the shadow of his own goal line. Army applied a big rush and, in his haste to get the kick off quickly, the ball went off the side of his foot and out of bounds at the Notre Dame 15-yard-line. After three running plays failed to produce any favorable results for Army, they called on Walter French to kick a field goal from 21 yards out. His kick was good and Army, to everyone’s surprise, took a 17–14 lead.

With time running out in the first half, Notre Dame had the ball inside its own 10-yard line. On fourth down Gipp got ready to punt the ball. Before the snap he pulled end Roger Kiley aside and instructed him to “tear down the left side,” where Gipp’s plan was to catch Army by surprise by foregoing the punt, in favor of a long pass. Gipp took the snap from center, dropped back, and launched a pass 45 yards down field to a streaking, wide open, Kiley. The throw was right on target, but uncharacteristically Kiley dropped the ball. Luckily for Notre Dame, Army was unable to capitalize on the excellent field position which resulted and as time ran out Army took a 17–14 lead into halftime.

In the locker room at halftime, Rockne was angry about Gipp’s gamble near the end of the first half, and generally not pleased with the situation in which Notre Dame found itself. It was in times like this that he would single out players that he thought had not played up to their potential. Eddie Anderson, who played end was one of Rockne’s targets on this day. “Anderson,” he barked “where were you on French’s runs?” As Anderson tried to explain, the coach shot back “don’t you talk back to me.” Then he turned his attention to Gipp. “And you there Gipp,” he said in voice dripping with sarcasm. “I guess you don’t have any interest in this game.” “Look, Rock, I’ve got four hundred bucks bet on this game and I am not about to blow it,” Gipp replied, evoking laughter from his teammates and even a grin from Rockne.20

“Before the third quarter the reporters in the press box wired their papers for extra space when they sensed that they were covering one of the great football games of all time. Never had they seen such a duel as that in progress between Gipp and French—and what might happen next was anybody’s guess.”21

Walter French kicked off for Army to start the third quarter. The kick coverage was excellent and pinned Notre Dame at its own seven-yard line. On the first play from scrimmage Gipp broke free on an end run and took the ball to the Army 45-yard line. Mohardt took the ball on the next play and advanced it 10 yards to the Army 35. The Army defense stiffened and Gipp missed a field goal from the 43-yard line.

Army was able to move the ball in their next possession but eventually the drive stalled, and Walter French was forced to punt. On its next drive Notre Dame went to the passing game. Gipp threw consecutive completions first to Mohardt and then to Kiley. Despite being set back twice by penalties Notre Dame would not be stopped. Chet Wynne carried the ball on two successive runs followed by Gipp who brought the ball to the Army 10-yard-line as the third quarter came to an end.

The fourth quarter began with consecutive runs by Gipp. It appeared that it would be three in a row when he faked a run, then pulled the ball back and sent a pass to Mohardt who easily took it into the end zone. After the extra point, Notre Dame jumped into the lead by a score of 21–17.

Army was unable to make any progress on its first drive of the fourth quarter and Walter French was forced to punt the ball away to Gipp who fielded the ball and ran it back 50 yards. On the next play Gipp connected with Roger Kiley on a pass play that brought the ball to the Army 20-yard-line. Notre Dame then ran a misdirection play with two running backs heading out to the flanks, and once the defense reacted, the ball was handed to Chet Wynne who took it up the middle for a touchdown. The extra point was missed, and the score stood at 27–17, which is how the game would end.

As the clock ran down and darkness fell at West Point, Gipp was removed from the game, having more than done his job. Gipp biographer Pat Chelland summarized his effort this way: “With his brother Alexander in the stands cheering him on, George Gipp had put on one of the greatest performances of his career. Gipp’s statistics were as follows: 150 yards rushing in twenty carries; 123 yards picked up as a result of five completed passes out of nine attempts; an additional 112 yards gained in running back punts and kick-offs. All of this against one of the greatest teams of the era.”22 It should also be noted that he generated those statistics in a game that was only 48-minutes long. In its coverage of the game the New York Times said “A lithe limbed Hoosier football player named George Gipp galloped wild through the Army on the Plains here this afternoon giving a performance which was more like an antelope than a human being. Gipp’s sensational dashes through the Cadets and his marvelously tossed forward passes enabled Notre Dame to beat Army by a score of 27–17.”23

After showering and dressing, Hunk Anderson made a quick trip to the Highland Falls businessman who had been holding the $4,200 that had been wagered on the game by the two teams. Gipp’s share of the winnings was $800 which would be the equivalent of about $10,000 in 2021.

Army center Frank Greene recalled how surprised he was to see Gipp after the game. After just completing a performance for the ages, Gipp looked emaciated and “literally down to skin and bones” when Greene saw him coming out of the shower room. As we shall see and sports fans everywhere would soon learn, that Frank’s concern for Gipp’s health would be a prescient one.

Today the 1920 game between Notre Dame and Army, simply referred to as “Gipp’s Greatest Game,” is listed by Notre Dame’s athletic department as one of the greatest moments in the school’s long and fabled football history. For Walter French, his heroic effort was overshadowed by Gipp. The headline in the New York Times the following day read, “Gipp Plays Brilliantly … French Also Shines.”24

Over the next few weeks Army played games against Lebanon Valley and Bowdoin, winning both by a combined score of 143 to 0. In the Bowdoin game, Walter French scored touch downs on runs of 40, 80, and two of 65 yards. This brought their record to 6–1 coming into the game against the 5–2 team from Navy, on November 27, 1920.

Army and Navy began playing football games against each other in 1890. Navy won that first game played at West Point 24–0 and between that first game and the one in 1920, the games were played each year with only three breaks. No games were played from 1894 to 1898. The series resumed in 1899 and continued until 1909 when the Army football program was disbanded after the death of a Cadet who was fatally injured in a game against Harvard. The series resumed in 1910 and the teams met annually until 1917. No games were played in 1917 and 1918 due to World War I.

Of the first four Army–Navy games, two were played at West Point and two at Annapolis. From 1899 to 1912 inclusive, all but one of the games was played at Franklin Field in Philadelphia. In 1913, 1915, 1916, and 1919 the games were played at the Polo Grounds in New York, which would be the case for the showdown in 1920. The two teams came into the game with similar records and the series, to that point, was essentially in a deadlock. Of the 22 Army–Navy games played prior to 1920, Army had won 11 and Navy had won 10 and the game played in 1905 ended in a 6–6 tie.

Like the years before and since, the 1920 Army–Navy game was among the year’s great sporting spectacles. Tickets for the game were in such high demand that the schools had to send out a warning to their supporters indicating that the sale of tickets to “speculators” would be frowned upon. The New York Times reported that “Major Philip Hayes, in a statement issued tonight, says that if members of the Army Athletic Association should be discovered putting their tickets up for sale, and should the responsibility for such unauthorized use of tickets be fixed, the responsible parties will be dropped from the rolls of the association and tickets in the future will not be sent to them.”25

In the lead up to this game the sportswriters focused on the matchup between Walter French and Navy captain Eddie Ewen. Newspapers featured a picture of the two, in a three-point stance, facing each other head-to-head on the front page of their sports sections. The caption read “When Army faces Navy there is always a display of artillery. While Uncle Sam’s military maneuvers are more or less secret, the dope is out that the elevens are mighty evenly matched for the annual game, which will be played at the Polo Grounds on November 27. French the speedy fullback will lead the Army boys in the attack against Captain Ewen, star end, of the Middies.”

Writing in the New York Herald on the Wednesday before the game, sportswriter William Hanna predicted that “Army’s fleet back, Walter French will be watched zealously by the midshipmen and isn’t going to have it any easier for having been heralded as one of the backs of the year. Right often in such cases the man thus exploited, and this sort of advance notice business is really unfair to him if he doesn’t come up to expectations.”26 The Herald article would turn out to be prophetic.

Over 48,000 fans were at the Polo Grounds under a gray sky and soggy conditions on the field. The New York Times described the scene this way: “There are football crowds and Harvard-Yale-Princeton crowds, and there is also the Army-Navy game crowd. It is composed quite largely of people, but, oh, what people! Of course, a lot of them are only human, but they seem rather more. What with the Generals and Admirals and thence downward; and what with the epaulets and gold and silver laces, the thousands upon thousands of uniforms and shoulder and sleeve straps, the average commonplace onlooker comes away feeling as if he himself were at least a diplomat.”27

The game kicked off at 2:12pm. Navy won the coin flip and elected to defend the west goal. Navy took the opening kickoff, running it back to the 20-yard line but after three running plays failed to pick up a first down, they were immediately forced to punt the ball back to Army. Walter French returned the kick 15 yards, but Army also failed to advance the ball and Walter had to punt the ball back to Navy. The punt came down near the Navy goal line and Navy quarterback Vic Noyes fielded it and was immediately dropped in his tracks by Army end Don Storck. Again, Navy was unable to advance the ball against the Army defense and had to punt from their own end zone. Walter French fielded the punt at the Navy 45-yard line and returned it 10 yards. After one running play and two pass attempts were unsuccessful, Walter French attempted a field goal from the 35-yard line. The kick was low and Navy took possession of the ball at their own 20-yard line.

After Navy made two first downs the Army defense stiffened and forced another punt. This time as Walter was waiting for the punt to come down, he was bowled over by the Navy ends covering the play before he had a chance to catch the ball. The play resulted in a 15-yard penalty and placed the ball at midfield but again they were forced to punt to Navy. Back and forth it went, with neither team able to sustain any drives.

The game’s first turnover occurred in the second quarter when Navy fumbled, and Army recovered the ball on Navy’s 25-yard line. After three running plays did not result in any progress, Walter attempted another field goal, and once again his kick sailed off target. Navy took over on their own 20-yard-line and began what looked to be a promising drive but that was cut short when Army intercepted a pass at its own 37-yard-line. Once again Army was unable to advance the ball and Walter tried his third field goal and this time from around midfield, and once again the kick came up short. The first half ended scoreless.

For the third quarter and most of the fourth, not much changed. The game was primarily played between the 40-yard-lines, with both teams unable to generate much in the way of offense. Navy’s focus on stopping Walter French was keeping him bottled up, holding him to less than 100 yards of total offense.

It looked like the game was going to end as a scoreless tie when late in the fourth quarter Army decided to punt one more time. Walter’s kicking woes continued with a bad kick that netted only 20 yards in field position. The ball glanced off the side of his foot and went out of bounds on the Army 47-yard-line. Navy backs Vic Noyes and Ben Koehler began banging away at the Army defense, which appeared to be tiring. A pass completion to Eddie Ewen brought the ball to the Army 27-yard-line and on the second of two dazzling runs by Koehler, Navy broke the deadlock with a touchdown. The extra point kick was good and the Midshipmen took the lead 7–0. Navy went on another drive just before the end of the game and brought the ball to the Army 14-yard-line but Noyes fumbled the ball and Army recovered as the game came to an end. The Navy win tied the series at 11 wins for each team, with one tie.

Newspaper accounts of Walter’s performance in the game were mixed. The New York Times, justifiably called him out for his poor kicking reading “French’s weak effort puts Navy in a position to start drive for Touchdown.” In its coverage of the game however, the New York Times also wrote “French, the Army fullback, of whom much had been expected, sometime showed flashes of real power in carrying the ball. However, he suffered in marked degree from the unstable footing, for the soil had not dried out from the recent rains.”28

The Army football team returned to the West Point campus at noon the next day, where they were met in the mess hall by the entire Corps of Cadets, who gave them a rousing cheer. “Full credit is given to Navy for its effectiveness in stopping French,” one paper reported, “something no other team has been able to do this season.”29

Army finished the season with a respectable 6–2 record, and with all of the team’s starters expected back for the 1921 season, prospects for the team’s future appeared bright. However, one person was not so sure. The team’s performance was disappointing to the Superintendent. MacArthur was miffed that, at least in his mind, Army could handle the inferior teams like Bowdoin and Lebanon Valley, but in the two most important games of the season against Notre Dame and Navy they came up short. A seed of doubt was planted in his head regarding whether Coach Daly was the man for the job.

The last bit of business was the naming of the year’s All-American team. As the 1920 season came to an end many newspapers and football experts were publishing their All-American teams. There were primarily four All-American selectors recognized by the NCAA at that time. Colliers Weekly Magazine, Football World Magazine, the International News Service, and the man considered the foremost expert on college football at the time, Walter Camp. In addition, sportswriters like Walter Eckersall of the Chicago Tribune and Lawrence Perry of the Consolidated Press also published their own selections as did the New York Times and the United Press International. Walter French was named to a number of the All-American Teams. He was selected as the first team fullback by the New York Times and Football World Magazine. Lawrence Perry named him to his second team as did UPI and the most respected of the selectors, Walter Camp.

As with virtually every selector, Camp’s first team fullback selection was George Gipp, making him Notre Dame’s first All-American. (Gipp was named to the New York Times first team as a halfback.) The teams were announced on December 15, 1920, but sadly Gipp would never know of his selection. Hospitalized in South Bend with a streptococcal infection, Gipp died from the ailment on December 14, 1920, the day before Camp’s and the other selectors’ picks were announced, and only six weeks after his greatest game. As the funeral cortege bearing Gipp’s body completed its over 500-mile trip from South Bend and pulled into his hometown of Laurium, MI, the entire town turned out to pay their respects to their favorite son. In the 100 plus years since his final game, only nine Notre Dame running backs have managed to amass more career rushing yards than the great George Gipp.

For Walter French the end of the football season meant that he was moving on to another sport at West Point and without much of a break. Of all Army athletes earning varsity letters in those years, Walter was one of only two to have done so in three sports, football, baseball, and basketball. At some point something had to give, and there were indications in early 1921 that for Walter, what was to give, were his grades. He ranked near the bottom of his 572-member class in almost every subject and he especially struggled in Math and English.

Coach Joseph O’Shea was in his second year as head coach of the Army basketball team. O’Shea was originally hired away from St. John’s prior to the 1919–20 season. The 1920–21 season got underway in early December of 1920 with a victory over St. John’s by a score of 55–14. Walter was a starting forward on the team which would compile an 18–5 record on the season. Wins came against teams like St. Joseph’s of Philadelphia, Villanova, University of North Carolina, Williams, and Brown while losses came at the hands of Columbia, New York University, Swarthmore, Pittsburgh, and worst of all Navy. The loss to Navy was particularly troublesome for coach O’Shea whose contract called for him to be paid $2,500 per season, unless his team lost to Navy, in which case his salary was reduced to $1,500.

A summation of the basketball season published in the Howitzer the West Point yearbook concluded that “Army’s 1921 basketball team attempted an extremely difficult schedule with a great deal of success, discounting that fact that Navy’s victory of February 26th, was, from a West Point outlook, a disastrous culmination to an otherwise very successful season.” For his part Walter was once again an important contributor to the Army cause. The Howitzer described his play this way: “Vichules and French teamed up well at forward and played brilliant games through the entire year … French was the fastest floor man on the team. He dribbled with great speed, followed the ball closely and was a good shot from the middle of the court.”30