CHAPTER 6

The Pottsville Maroons and the Stolen NFL Championship of 1925

As the 1925 baseball season came to an end, Charlie Berry, who was a reserve catcher for the Athletics had signed on to play for the Pottsville Maroons in the fledgling National Football League. Berry had joined the Athletics in June of 1925 and had only played in 10 games over the remainder of the year. He had been a standout end at Lafayette College and was selected by Walter Camp as a first team All-American for the 1924 college football season. Like Walter French, Berry was a native of New Jersey.

There is no way to know for sure, who approached who, but at some point, Walter French had decided that he wanted to join Berry on the Maroons for their 1925 season. There was just one catch, unlike with the sparingly used Berry, the A’s manager had just announced that French was going to be the Athletics starting right fielder in 1926. This was a completely different scenario from when he played football after his first minor league season in 1923. This would need to be cleared with Mr. Mack.

Connie Mack initially balked at the idea of allowing his emerging star outfielder to play in the National Football League. Mack had raised French’s salary from $3,000 for the 1925 season to $5,000 for 1926 but Walter argued that the money he would make playing for the Maroons was desperately needed now that he was a father. In a 1939 interview with Frank Graham, Walter recalled the exchange with Mack. “I told him that I wanted to play football for Pottsville in the National Football League, he did not like the idea very much at first. Nowadays I don’t suppose any baseball manager would let one of his players play football, even if he was just a kid who hadn’t yet proved that he was a big leaguer. But I showed Connie where I could make some dough that I really needed now that I had a wife to support, and he gave in after a while.”1

Pottsville, Pennsylvania is located in Schuylkill County and sits along the west bank of the Schuylkill River. Schuylkill County was home to large anthracite mining operations. Anthracite is also referred to as hard coal and is the highest ranking of coals. Although today anthracite is mined in a number of countries around the world, the first commercial mining in the United States was in Pennsylvania.

Working in the mines was the principal occupation of the people of Pottsville and the surrounding communities in the 1920s. The work was dangerous and backbreaking, and as if their jobs weren’t hard enough, the men would play pick up football games when they had a few minutes to themselves. Eventually these games began to draw crowds from the residents of the area, who would come out to cheer for their town’s team. Soon people began gambling on the games and eventually a semi-professional football league was formed in 1924. Because it was made up of teams from towns in the anthracite coal mining region the league was known as the Anthracite Association. The team from Pottsville, known as the Maroons, was far and away the best team in the League.

The Maroons’ owner was a local surgeon named John G. “Doc” Striegel and after the team dominated the Anthracite league in 1924, going 12–1–1 and easily winning the league championship, he began to set his eyes on the National Football League. Striegel believed, and with good reason, that his team could compete with any of the teams in the NFL. The Maroons were led on the field by Tony Latone, who had been Walter French’s teammate when they both played for the Gilberton Catamounts in 1923.

“I can get this team into the National Football League if the patrons so desire it,”2 Striegel challenged the Maroons’ supporters. The key in his quest was the game between the Maroons and the team from Atlantic City, which was being played in Atlantic City on November 9, 1924. If the Maroons’ fans could show up in sufficient numbers in Atlantic City, the NFL would be hard pressed to deny a franchise to Pottsville. Striegel was “as confident with the prospect of thousands of his patrons showing their allegiance and admission ticket buying power as he was that the Maroons could win the game.” So many fans from Pottsville wanted to attend the game that the “railroads were called on to aid the movement with three extra cars.”3

The Maroons won the game easily, but the turnout, estimated to be nearly 5,000, was really the big story.

After Olympic legend Jim Thorpe served a short term as league president of the National Football League, the owners appointed Joe Carr, the owner of the Columbus Panhandles, to fill that position. Believing that it needed a set of rules, Carr created the league’s first charter and by-laws and he saw to it that they were strictly enforced. In 1922, when the Green Bay Packers were caught using college players, which was a practice forbidden under Carr’s rules, he kicked them out of the league. When Curly Lambeau took over the team, he was able to have them reinstated for the 1923 season, but Carr had made his point that teams needed to adhere to his rules, or they would be severely penalized. That was especially true for the small market teams. Carr knew that the future success of the league would depend on its acceptance in large metropolitan areas. The purpose of the small market teams, in his view, was to fill out the schedule, but in the long term he wanted to transition the league away from what he thought of as unsustainable small-town franchises.

Doc’s guests on the sideline of the game with Atlantic City were the Stein brothers, Russ and Herb. As with Tony Latone, the Stein brothers had played with Walter French in 1923 on the Frankford Yellow Jackets, Philadelphia’s NFL team and they were also on the team in 1924. The Stein brothers were the foundation of the Yellow Jackets’ offensive and defensive lines.

Shortly after the game in Atlantic City, Striegel visited the Stein brothers and offered them a contract for the upcoming season. Shep Royle, who was the owner of the Yellow Jackets, was waiting until closer to the opening of the season to offer the Steins a contract for 1925, as was customary in the early days of the NFL. However, Doc’s quick action and generous offers convinced the brothers, two of Frankford’s best players, to jump to the Maroons.

A short while after landing the Stein brothers, Doc Striegel attended a game at the University of Pennsylvania, which was his alma mater, to scout some players for his team. It was at this game that he saw Charlie Berry for the first time along with quarterback Jack Ernst both of whom were playing for Lafayette. Within a short period of time Berry and the strong-armed Ernst were both signed to the Maroons.

The turnout at the game in Atlantic City along with Joe Carr’s belief that the Maroons would be crushed by any NFL team and put an end to any challenge to his league’s dominance, opened the door to the Maroons’ admittance into the National Football League. Doc Striegel met with Carr and the other owners and paid his $500 for the franchise fee along with a guarantee of $1,200 and they were in.

To coach the Maroons in their inaugural season Doc Striegel selected Harrisburg, PA native Dick Rauch. After graduating from high school in 1910 Rauch went to work in the steel mills near his home for six years. In 1916, he entered Bethlehem Preparatory School and was eventually accepted into Penn State. After playing football on the Freshman team at the school he made the varsity squad in 1917. His college career was interrupted by World War I as Rauch entered the Army, returning in 1919. As his time at Penn State progressed, he became a favorite of the school’s legendary coach Hugo Bezdek and when he graduated in 1921, he was given a job as assistant coach. In 1923, he moved on to be the offensive line coach at Colgate.

To say that Dick Rauch was an interesting character would be a major understatement. Besides being a football coach, Rauch was a serious ornithologist and traveled all over North America studying the habits of all species of birds and in his spare time he also wrote poetry.

Clarence Beck, who was the player coach of the Maroons in their last year in the Anthracite league, recommended Rauch to Doc Striegel. Making Rauch an offer would have to wait until he returned from a bird watching expedition in the late summer of 1925 but when they finally were able to meet, Doc made Dick a very attractive offer which he accepted with certain conditions. “The team would practice regularly. Not only would players be expected to live in Pottsville but they would become active members of the community. Rauch knew that the players had their work cut out for them.” It turned out that Doc was on the same page as his new coach and agreed with all of the conditions.4 Doc and Dick also shared a vision for the approach the Maroons would take in terms of the type of game plan they wanted to institute. Both men were keen on installing a style of play more in keeping with that being played at the collegiate level which was considered vastly superior to the professional game.

With the team’s core players in place, Doc proceeded to extend himself financially to put together a roster that would challenge the best that the NFL had to offer. To add to the line, he signed former All-Big Ten lineman from the University of Indiana Russ Hathaway, added end Frank Bucher from Detroit-Mercy and the fleet-footed Hoot Flanagan who had played for Pop Warner at the University of Pittsburgh. He also added Penn State fullback Barney Wentz and former coal miner and semi-pro legend Frank Racis who could play any number of positions on the line. Walter French and Charlie Berry would have to wait until the baseball season was over before joining the Maroons.

The Maroons’ home field, Minersville Park, was a converted High School Stadium with a capacity of 5,000 which was small for an NFL team even in 1925. Minersville Park was the site of the Maroons’ first NFL game against the Buffalo Bisons, on September 27. The Bisons were the worst team in the league at that time. They would finish with a 1–6–2 record and only score three touchdowns all season. The Maroons made short work of the Bisons coming away with an easy 28–0 victory.

Next on the schedule was another home game against the Providence Steam Roller. The first of two games between the teams in the next three weeks. The Pottsville Republican reported however that the Maroons were “slightly crippled” coming into the game. “Hoot Flanagan and Harry Dayoff will be lost to the backfield.” Flanagan was reported to have an “infection in his arm,” and Dayoff “pulled a tendon.” The newspaper also reported that “French and Berry were not at practice” which should not have been a surprise because on the day before the Providence game, Walter French was batting in the fifth spot in the Philadelphia A’s lineup and getting two hits in three at bats with three RBI.5

The weather in Pottsville on the day of the game was terrible with heavy rains pouring down throughout the game. Neither team could mount much of a sustained offense, but the Maroons were clearly getting the best of Providence. They would finish the game with 15–0 advantage in first downs. However, after a scoreless first half, with the Maroons deep in their own territory, substitute center Denny Hughes snapped the ball before the backfield players were set and the loose ball went bounding toward the end zone. Providence player Red Maloney scooped up the ball and ran a few yards into the Maroons’ end zone for the game’s only score. The Maroons attempted a comeback but frustratingly kept turning the ball over to Providence. As good as the Maroons were, the loss to Providence revealed a weakness in the way the team was constituted. On offense they were too one dimensional and overly reliant on the running of players like Tony Latone, but help was on the way in the persons of Charlie Berry and Walter French. They would give Coach Rauch the opportunity to run the wide open, collegiate style of play he so desired.

Four days after the loss to Providence, a headline in the Pottsville Republican predicted “Walter French to Get Going.” The article went on to explain that “Fans will more than likely get a slant at Walter French, the former Army star, now with the Pottsville Maroons when the Canton Club lines up against the locals in the next game. French has been drilling with the first squad the past few days and has mastered the signals. Coach Dick Rauch is working him in at a regular halfback job and it is thought that Rauch intends on showing him to the public in the next game.”6

The Canton Bulldogs came into the game with a record of 2–1. They sustained their first loss of the season at the hands of the Frankford Yellow Jackets, the day before the game with the Maroons. After a scoreless first quarter, Hoot Flanagan, just off the injured list, ran for a five-yard touchdown and Charlie Berry, in his first game of the season, kicked his first of four extra points to give the Maroons a 7–0 lead at halftime. In the third quarter Berry blocked a punt and scooped up the ball and ran it in for a touchdown which with the kick gave the Maroons a 14–0 lead. Later in the third quarter Flanagan ran in his second touchdown of the day and with Berry’s kick the Maroons extended their lead to 21–0. Tony Latone finished off the scoring with a one-yard plunge into the end zone in the fourth quarter.

The Maroons’ fans were encouraged by the improved play of their team. While Berry played the entire game and was one of the Maroons’ heroes, Walter French did not get into the game until the fourth quarter. The Republican explained that “Berry was in the entire game at left end and the former Lafayette star looked mighty good. He has made the grade and will be a permanent fixture on the Maroons.” The newspaper’s review of the play of Walter was positive as well. “The former West Pointer showed some of his old-time speed when he replaced Wentz in the fourth quarter. He got off one fine end-run displaying to the spectators that he still possesses a lot of speed and cunning that made him famous in college football.”7

Next on the Maroons’ schedule was a rematch with the Providence Steam Roller on October 18 in Providence. In the lead up to the game the Republican assured the Pottsville fans “That the squabble over the club’s finances has not affected the morale of the club was evident by the final practice. The boys went through the daily workout with just as much pep and vigor as they did on the eve of many a college in the past.”8

The newspaper also reported that Coach Rauch had “perfected a fast interference for Walter French and it is believed that he will be used in a greater part of the Providence game than any to date” and adding that “the Maroons’ plan of attack will be changed so as to compel the Steam Rollers to change their defense.”9 There would be no repeat of the first game against Providence.

The Maroons left Pottsville on Saturday, October 17, taking the Reading Railroad to New York City. From New York they traveled by boat to Providence, RI. Every member of the 16-man Maroons’ squad was healthy and ready for action.

By combining their normal powerful straight ahead running attack with some passing and end runs the Maroons completely overwhelmed the Providence team and exacting what the Republican referred to as “sweet revenge” in the process. The 10,000 fans, including a contingent of Maroons’ fans, that packed the Providence Cycledrome witnessed a game that bore no resemblance to the first meeting between the two teams. The Republican reported that “from the beginning to end it was a series of gains by Latone, Wentz, and Flanagan, with touchdowns the ultimate result in nearly every case.”10 The Maroons scored three touchdowns in the fourth quarter alone. “French” the Republican reported “substituting for Flanagan carried off long distance running honors when he got away in the fourth quarter for a dash of 34 yards. On this play French followed his interference as far as the line of scrimmage then swung across and completed the remainder of his journey unaccompanied and, incidentally, was not tossed until Ogden halted him near the Rollers citadel.”11 The game ended in a 34–0 victory for the Maroons.

At 5'7" and 155 pounds, Walter French was by far the smallest of the Pottsville Maroons. His secret to success in sports throughout his life was his quickness and speed, which he had in abundance. Beginning with his time at Moorestown High School his brilliant speed was his calling card. Ironically, he was not even the fastest runner at Moorestown. His teammate on the school’s track team was future Olympic Gold Medal winning sprinter Alfred LeConey. LeConey, like three of the Pottsville Maroons (Berry, Millman, and Ernst) was a star athlete at Lafayette College. In 1922 LeConey won the AAU Championship in the 220-yard race and was known as the “Fastest Man in the East.” At the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris he ran the anchor leg in the 4x100 meter relay which won the gold medal in a world record time of 41.0 seconds. Movie buffs will remember that the 1924 Olympics were featured in the Academy Award-winning film Chariots of Fire. Finishing second to LeConey in the relay race was Harold Abrahams, one of the athletes featured in the movie.

Due to his small physical stature, the local sportswriters began referring to French as “Little Walter” and if he ever formally objected to the moniker no record of it exists. At Army he was often referred to as “Fritz,” a nickname he used when signing autographs, which he preferred. However, to judge his physical abilities by simply comparing his height and weight to that of his teammates is to ignore the fact that he was built as sturdy as they come. Pictures of him in his playing days reveal someone without as much as one ounce of body fat. He possessed big muscular arms, shoulders, and legs. In a picture of him taken in his Army football uniform one notices that he had hands that were as big as those of someone twice his size but like it or not “Little Walter” would be his nickname on the Maroons.

The next opponent for the Maroons would be a home game against the Columbus Tigers from Columbus, Ohio on November 1. It would be one of two games that Walter found himself in the starting lineup. On the opening play of the game, he took the kickoff back 25 yards. After Berry caught a pass and Latone and Wentz smashed through the Columbus line for nice gains, Walter broke free on a 15-yard run to the Columbus 30-yard-line. There the Maroons drive stalled. Columbus was unable to move the ball against the Maroons’ defense and was forced to punt. A slew of Maroons blocked the punt, and the ball traveled a number of yards in the air and eventually Barney Wentz grabbed it and raced with it to the Columbus one-yard-line. The Republican described what happened next: “Little Walter showed his real stuff to the fans next. Something happened. What it was is not exactly known. It looked as if somebody got the signals balled up and when Denny snapped the ball there was nobody there to get it. This happened in the Providence game and Maloney scored on it but not this time.”12 As the ball rolled back to the 20-yard-line Walter bolted back like he had been shot out of a gun, scooped up the ball and began to run to the far side of the field he then cut back and reversed direction, dodging would-be Tiger tacklers until he had the ball back at the Columbus one yard line. It was about as pretty a run as the fans had seen to that point of the season and when it was over Walter again had the ball in position to score. And score they did. On the next play Tony Latone plowed his way into the end zone. Charlie Berry kicked the extra point and the Maroons took a 7–0 lead. After reeling off several long runs in the remainder of the first and second quarter, Walter brought the Maroons’ fans to their feet one more time. As the third quarter was winding down, he took a handoff and sped around the right end, following his blockers and eluding tacklers, he sped down the sideline for a 30-yard-touchdown to close out the scoring and give the Maroons a 20–0 victory.

Walter’s performance had electrified the Maroons’ fans, who, as was customary, had bet heavily on their team. One former player recalled that “after games the miners would be pushing ones and fives at you-passing you a cut of the money they had just won betting on the Maroons.” He recalled that “following the Columbus victory on November 1, by the time Walter French made it back to the Maroons, he looked like a scarecrow stuffed with greenbacks.”13

It is hard to imagine a fan base more rabid than that of the Maroons. The importance of the team to Pottsville was amplified in 1925 by a coal miners’ strike, the third in a five-year period, that devastated the region’s economy. The miners, represented by the United Mine Workers of America, were seeking an increase in wages and maintenance of the “checkoff system,” which increase the power of the union by allowing for closed shops.

As the showdown with their rivals the Frankford Yellow Jackets approached, The Morning Call, an Allentown, PA based newspaper wrote that “there may be a coal strike and many anxious faces in the anthracite region around here, but one silver lining in the clouds is the powerful Pottsville Maroons, the classiest collection of football players that has ever represented this section. The one topic of conversation in Pottsville and the surrounding towns this week is ‘Will the Maroons beat the Frankford Yellow Jackets on Saturday.’”14

After easily defeating the Akron Pros on November 8 by a score of 21–0, the team had finished a four-game stretch in which they did not allow a single point to be scored against them and speculation was that the game against Frankford would go a long way to determining the NFL championship. It was anticipated that over 1,000 of the Pottsville faithful would make the trip to Philadelphia along with a 40-piece band to “back up the prowess of Charlie Berry, Walter French, Jack Ernst, et al. against the powerful Yellow Jackets of Philadelphia.” The fans were optimistic because the same Akron team that the Maroons shutout “with French and other stars on the sideline” made a much better game of it against Frankford losing 17–7.15

“Walter French, outfielder from the Athletics, and Charlie Berry, the Mack men’s rookie catcher, obtained permission to play football this fall” the Morning Call reminded its readers, adding that “French received his football training at Moorestown High, Rutgers, and West Point while Berry was an All-American at Lafayette.”16

After his performance against Columbus, Walter assumed a much higher profile with the sportswriters and the fans. Interviewed for the Morning Call, Walter spoke for the entire Maroons’ team. “We just have to win for this town” he told the newspaper, “They’ve backed us to the limit in spite of business troubles and the people have enough civic pride to lay their last dollar on us to win. It will take a better team than ours to beat us. We have a great line with two stars in Hathaway, late of Indiana, and Russ Stein of Pitt, and our backfield featuring Barney Wentz, Latone and Ernst isn’t so bad. Charlie Berry, of course, is the best end in professional football. It’s going to be a great game and everyone can rest assured the Maroons will do their best … we can do no more. We are not overconfident or boastful. We figure we are in for a hard game.”17

It is not surprising that Frankford and Pottsville were bitter rivals. Frankford was a small independent borough until it was annexed by Philadelphia in 1854. The team’s owner Shep Royle and their fans all looked down their noses at Pottsville as being a mere coal town, while the Pottsville faithful considered the Yellow Jackets and their fans to be snobs. Adding to the natural dislike the two teams had for one another, was the small matter of Doc Striegel signing the Stein brothers away from Frankford at the beginning of the season, a move that the Jackets’ owner Shep Royle would never forgive or forget.

The Maroons came into the game with a 5–1 record and having only allowed six points to be scored against them to that point in the season. The Yellow Jackets, on the other hand, had played almost twice as many games and stood at 9–2, and on this day that experience won out. The Maroons took the opening kickoff and began to march the ball 79 yards downfield and all seemed to be right in the world. However, rather than punching the ball into the end zone, they were stopped when Tony Latone dropped a pass on fourth down. Things for the Maroons went downhill from there. The Philadelphia Inquirer summed up the contest writing “Fans saw a Pottsville team completely swept from the field, wilt, and fall before the onslaught of captain Russ Behman’s eleven. They saw a relentless Hornet, carry on in such a marvelous fashion that Pottsville never loomed as a winner and in only three instances during the entire fuss even threatened to score.”18 So the Maroons limped back to Pottsville, victims of a 20–0 drubbing, while their bitter rivals had put themselves in a perfect position to make a run at the NFL title.

Any dwelling on the loss to Frankford or time spent licking wounds, would have to wait. The Maroons still had a chance at the title. They had five games remaining to be played in the season starting with one against the Rochester Jeffersons the very next day.

Although the remaining games on the Maroons’ schedule included a rematch with Frankford, the Maroons could not look past Rochester given that the Jeffersons had not played in four days and would undoubtedly be fresher than the Maroons. “Walter French ran back a punt for forty yards” and then “broke loose again for fifteen yards”19 setting up the Maroons’ first touchdown by Latone. With the Maroons clinging to a 7–6 lead in the third quarter Ernst and Berry connected on a series of pass plays which took the Maroons the length of the field and into the end zone and with Berry second extra point kick of the game, they took a 14–6 lead. From there they hung tough in the fourth quarter and despite a furious comeback attempt by Rochester, kept them out of the end zone.

In 1925, there were no playoffs in professional football. Post-regular season playoff games would not be introduced to the NFL until 1933. The team with the best regular season record when all the official games were completed would be declared the champions. Prior to 1925 November 30 was the cutoff for games to be completed to count as the “regular season,” but at the league meetings at the start of the 1925 season it was moved back to December 20. And so, when word reached Pottsville, as they were preparing to play the defending NFL champions, the Cleveland Bulldogs, that Frankford had lost both games they played over the weekend, the Maroons understood that their fate was back in their own hands. They were now in essentially a five-way tie at the top of the standings with Frankford, the Detroit Panthers, the New York Giants, and the Chicago Cardinals.

With a full week’s rest, the game against Cleveland on November 22 was much more of what the Pottsville fans had come to expect from the team. Jack Ernst ran a punt back 55 yards for the games first score. Tony Latone intercepted a pass and ran it back 45 yards for the Maroons’ second touchdown. Charlie Berry kicked a 29-yard field goal to move the score to 17–0 and then Walter French scored his second touchdown of the season going around the end for 12 yards to ice the game.

The win over Cleveland left only one more hurdle before the rematch with Frankford and that was a home game against the Green Bay Packers on Thanksgiving Day. The Packers were founded in 1919 by Curly Lambeau, who was still serving as player-coach for the team. For Walter French going up against Curly Lambeau now meant that he had gone head-to-head with two of the NFL’s founding fathers, after having played against George Halas, founder of the Chicago Bears, while playing for Rutgers in 1918.

In the game against the Packers, the Maroons’ captain Charlie Berry put on a football clinic. The Maroons scored 24 points in the first half of the game and Berry was responsible for all of them. He caught two touchdown passes for a total of 47 yards, scooped up a blocked punt and ran it in for his third touchdown, converted all three of his extra-point kicks and then topped it off with a 28-yard field goal. The final score was 31–0 and the victory marked the sixth time in the season that the Maroons had not allowed an opponent to score a single point. The stage was set for the rematch with Frankford three days later on November 29.

“The Frankford rematch was shaping up to be the biggest sporting event in Pottsville history,” wrote Dave Fleming, adding “The Hotel Allen was filled to capacity with sportswriters from all over the East Coast and VIPs like Curly Lambeau and Tim Mara, the owner of the New York Giants. The Reading Railroad company had to add 11 extra cars to a train from Philadelphia. Football fans came from as far west as Cleveland, as far north as Rochester, east from Boston, and south from Washington, D.C.” As game time was approaching “more than 11,000 fans had assembled in and around Minersville Park.”20

As if things were not tense enough Coach Rauch, as part of his pregame speech confirmed that a game was being planned to be played by the eventual NFL champs against the members of the 1924 Notre Dame legendary Four Horsemen team. The 1924 Notre Dame team had turned in an undefeated season, won the national championship and were considered by the experts, and fans alike, to be simply the best football team ever assembled. It is hard to imagine today, but in the early 1920s there was no debate about the fact that, in football, the college game reigned supreme. That was especially true of the 1924 “Four Horsemen” team.

However, it is not difficult to imagine what was going through the minds of the Maroons upon hearing this news. Some may have thought of the glory that a victory in such a game would bring, some may have thought “let’s just get through today’s game please,” but all of them would have no doubt been thinking about the payday that would be in store.

Right from the opening kickoff the Maroons’ fans knew this game was going to be a very different affair from the first game between the two teams. Hoot Flanagan returned the opening kickoff 30 yards to the Maroons’ 40-yard-line. This was followed up by a few pass completions from Ernst to Berry, and some tough running by Tony Latone who finished the drive with a one-yard touchdown run. With the Maroons’ line dominating the line of scrimmage they quickly moved the ball deep into Yellow Jacket territory before the drive stalled. Much to the chagrin of the fans, Coach Rauch opted to go for a field goal and Berry converted.

The next time the Maroons got the ball, Latone took a handoff and crashed into a host of Frankford defenders. When he emerged from the bottom of the pile of tacklers, he was clutching his elbow and needed to be helped to the sideline. The team’s star had been silenced and so were the fans, all fearing the worst.

The Yellow Jackets, sensing an opportunity to turn the tide of the first half began to methodically move the ball down field. Deep in Maroons’ territory Ralph Homan dropped back to pass and at that moment Hoot Flanagan noticed Bob Fitzke of the Jackets sneaking out of the backfield and running a pass pattern. Flanagan jumped in front of Fitzke just as the ball was arriving and not only intercepted the pass but also ran it back 90 yards for a Maroons touchdown to give them a 16–0 lead at half-time.

In the locker room at half-time, Doc Striegel examined Tony Latone’s injured elbow and determined that, at best, he would be lost to the team for the remainder of this game. Coach Rauch, adjusting for the loss of his star player, called on Jack Ernst and the passing game, which included a bigger role for Walter French and Charlie Berry, to hold off the Yellow Jackets, and hold them off they did. Ernst, “as cool as a cake of ice in the Polar Sea”21 according to the Republican, proceeded to complete his first seven passes bringing the ball to the Yellow Jackets’ one-yard-line before the team from Philadelphia ever knew what hit them. From there Latone’s replacement at fullback, Barney Wentz, took the ball in for a touchdown. The Maroons now had a three-possession lead and the Yellow Jackets went to the passing game in an attempt to close the gap. This was to no avail as Hoot Flanagan once again intercepted a pass and this time ran it back 45 yards for a touchdown. Walter French made his presence felt in the fourth quarter. First, he caught a pass from Ernst and took it 30 yards for another Maroons touchdown. A few minutes later he caught another pass and this time raced 45 yards for the touchdown that closed out the Yellow Jackets. The Maroons had their revenge, coming away with a dominating 49–0 victory over their bitter rivals. “Against teams like Canton, Cleveland and Green Bay the Maroons followed the canon of good sportsmanship and eased up late in the game. But this was Frankford, and Shep Royle had it coming.”22

After the Frankford game the Maroons fully expected that their next game would be against Notre Dame on December 12 in Philadelphia. The morning after the Yellow Jackets game the prognosis on Tony Latone’s injury had improved and Doc Striegel was confident that with a week off that he would be ready for the game against Notre Dame. All seemed well with the world, however, here is where the story of the Maroons and the 1925 football season, takes a twist.

On November 26, Thanksgiving Day, while the Pottsville Maroons were handing the Packers a 31–0 defeat, Harold “Red” Grange, a three-time consensus All-American halfback at the University of Illinois turned professional signing a contract with the Chicago Bears. Nicknamed the “Galloping Ghost,” it would not be an exaggeration to state that Grange was to football in the 1920s what Babe Ruth was to baseball. His first game, on Thanksgiving Day, was against the Chicago Cardinals at Wrigley Field. Over 36,000, the largest crowd to ever attend a professional football game were on hand to see him play but had to have been disappointed when the game ended in a scoreless tie. The tie left the Cardinals with a 9–1–1 record, and a one-half game lead over the Maroons in the standings.

Three days later, on November 29, while the Maroons were handing Frankford their beating, 20,000 people showed up to watch Grange and the Bears play the Columbus Tigers. Coming into the game the Bears had a record of 6–2–3 and had lost badly to the Cardinals the week before Grange joined the team. It was clear that George Halas and the Bears had struck gold with the signing of Grange, much to the chagrin of his crosstown rival Chris O’Brien, owner of the Cardinals.

Under the rules put in place before the 1925 season, teams could schedule games with each other even if they were not on the schedule at the start of the season, and as long as they were not played after December 20, they would count in the league standings. So it was, that O’Brien, looking to cash in on the fact that Grange and the Bears were departing from Chicago for a seven game, two-week road trip, reached out to Doc Striegel with a proposal O’Brien felt could draw a crowd like those turning out to watch Grange. O’Brien suggested that a game be played between the Cardinals and the Maroons on the following Sunday at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Doc, sensing an opportunity to win the league title on the field, accepted despite the disadvantage the logistics presented, and despite the fact that his team would be without Tony Latone, whose injury Doc knew would need another week to heal. They also faced the added pressure from the fact that “if they were to lose to Chicago, there was no guarantee Frank Schumann, the promoter of the Notre Dame game, wouldn’t dump them in favor of the Frankford Yellow Jackets for the World Championship. Because of that scenario, many in Zacko’s crew were convinced that the whole idea of a Cardinals–Maroons NFL title game had been brokered behind the scenes by none other than the nefarious Shep Royle.”23 None of that mattered to Doc. He accepted the challenge and “was about to call the league’s bluff one more time, push his chips into the center of the table, and ask his team to do the impossible all over again.”24

In the lead up to the game, newspapers in both Illinois and Pennsylvania billed the game as the league championship. Victory for the Cardinals, according to the Chicago Tribune “would clarify any dispute as to the championship. Pottsville claims the championship of the Eastern Division of the league. The Cardinals rule the Western end.”25

The International News Service also weighed in on the significance of the two teams meeting writing “The national professional football title will be at stake when the Pottsville eleven, winners of the East Division of the National Professional Football League, and the Chicago Cardinals, winners of the Western Section, meet in the White Sox Park here tomorrow.”26

On the morning of the game the Chicago Tribune reiterated this point “The National Professional Football League championship hangs in the balance today when the Chicago Cardinals and the Pottsville, PA eleven clash on the gridiron at Comiskey Park. A victory for either team carries the national title, for the Cardinals have swept over all opponents in the western half of the league while the Pottsville eleven holds the eastern crown.”27

The Maroons boarded a train for Chicago on the morning of December 5 and as they approached Chicago, they ran into a major snowstorm that had hit the region and by game time the field was covered with snow and ice.

Only about 100 Maroons fans made the trip to Chicago and the rest of the faithful made their way to Pottsville’s Hippodrome Theater where they were able to hear a rudimentary “play by play” of the game. A direct wire was installed from the playing field to the stage at the theater and, for a fee of 50 cents, fans could learn about the game within seconds. The telegrams from Comiskey Field consisted of game updates tapped out in Morse Code and read out to those in attendance.

Coach Rauch, in preparing for the game with the Cardinals, focused his defense on stopping their star player, halfback, John “Paddy” Driscoll. Driscoll had been one of the stars of the Great Lakes Naval Station team that had trounced French’s Rutgers team back in 1918. He assigned the task to the Stein brothers, who were to shadow Driscoll almost to the exclusion of any other members of the Cardinals offense. If someone on the Chicago team was going to beat the Maroons on this day, it was not going to be Paddy. On the offensive side of the ball, Rauch was counting on the fact that the severity of Tony Latone’s injury was unknown to the Cardinals and that their game plan would focus on stopping the straight ahead, smash mouth type of play that made the “Human Howitzer” the star he was in the league. Which is exactly what they did. The fact was that if Latone got in the game at all, it would only be as a decoy and with Latone out for the game, the running duties would be shared between Walter French and Hoot Flanagan.

Over 10,000 fans, despite the cold and snow, jammed Comiskey Field, including baseball commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis, who made a special point of wishing good luck to Walter French and Charlie Berry.

On the first series of the game Hoot Flanagan ran a reverse around the right but as he struggled to maintain his balance on the icy field, he fumbled the ball and it was recovered by the Cardinals at the Maroons’ 40-yard-line. On the next play Driscoll drifted out of the Cardinals’ backfield and caught a pass which brought the ball to the Pottsville 12-yard-line, however from there the Maroons’ defense stiffened and the Cardinals’ drive stalled. The rest of the first quarter played out the same way and ended in a scoreless tie. In the second quarter Jack Ernst fielded a punt and following his interference beautifully and breaking tackles he took the ball all the way to the Cardinals’ five-yard-line. A few plays later, on third down, Barney Wentz took the ball the rest of the way for the game’s first score. Berry kicked the extra point and the Maroons took the lead 7–0.

Back at the Hippodrome in Pottsville, the crowd was ecstatic with the news of the touchdown, however they would be brought back to earth when the news came across the wire that Hoot Flanagan was being helped from the field. Blocking for Wentz, Hoot had gone down hard on the frozen field and had broken his collarbone. Suddenly Walter French was thrust into the role of the featured running back.

When Walter entered the game in place of Flanagan the Chicago Tribune described what happened next: “Flanagan of the Pennsylvania team was taken off the field with a broken collarbone and the stage was set for the entry of Mr. French, the fast-running Army boy. French immediately got into action. He took the leather and raced downfield 30 yards before he skidded and was downed. A couple of line plays followed and then Mr. French got his second wind and took the ball again on another romp around the Cardinals’ right end for 30 more yards and a touchdown. Three Cardinals tackled French in the course of his run, but he shook them all off. Berry again kicked the goal.”28 Down 14–0 the Cardinals tried to grab some momentum through the passing game with some success, eventually scoring a touchdown to cut the Maroons’ lead to 14–7. “That ended the action except for a flash in the final period when Pottsville staged another big drive up the field with French tearing and ripping his way through the line and around the ends, and then Wentz dove off tackle for three yards and the final touchdown.”29

For the Cardinals’ right end, Eddie Anderson, Walter French’s performance must have seemed like déjà vu. It was the same Eddie Anderson who, while playing end for Notre Dame in 1920, had incurred the wrath of Knute Rockne after Walter repeatedly beat him to the corner on his end runs.

The newspaper stories written after the game focused on two themes. The first was that the win by the Maroons constituted the league championship. The Chicago Tribune headline read “Pottsville Wins Over Cards and Takes Pro Title, 21–7.” The sports section in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin led with “National Title: Downs Chicago Cardinals 21–7, in East–West Play-Off of National Football League.” The Philadelphia Inquirer headline read: “Maroons Conquer Cards, Take Crown.” The Evening Herald in Pottsville shouted: “Maroons Are Now Hailed As the Champions.”

The second theme, in the coverage of the game, was that its star was Walter French. The headline in the Philadelphia Record read: “French Scores TD, Runs Wild For Miners in Rout of Chicago, 21–7. Pottsville Player, who cavorts in the outfield for Athletics during the summer, hero in winning of National Crown.” The Chicago Tribune summed up Walter’s performance this way: “The whole show was centered around a slippery, cagey fellow named French, who gained quite a reputation as a back with the West Point eleven a few years ago … It was French more than anyone else on the Pottsville team who wrecked the Chicago title hopes. He bobbed up in play after play and the yardage he gained would make Red Grange sit up and check back in his notebook.”30 The Philadelphia Inquirer added: “the ex-Army gridder bucked the line. He hurled passes. He caught passes. He ran the ends. He punted. In each of these departments he showed so much skill that even the work of the brilliant Paddy Driscoll was overshadowed.”31

Despite the lopsided score however, the Cardinals gave as good as they got physically during the contest. A number of the Maroons emerged from the game with injuries. In addition to Flanagan’s season ending broken collarbone the Republican reported that “French’s nose is not broken as was first feared, but he suffered a slight concussion of the brain from which he is expected to recover in a few days. Beck has an injured hand which may prove to be a fracture. Hathaway also has an injured hand and a black eye.”32

For Walter this marked the second, documented time that he had sustained a concussion playing football. Although it did not appear to be as serious as the one in 1919, he did decide to remain in Chicago for a few days after the game to, as the newspapers reported, “spend a few days with relatives.”33 Conveniently one of the “relatives” was Beth’s cousin Martha Dent who was a nurse.

The good news was that Latone’s injured elbow was protected in the matchup with Chicago and the prognosis was that he would be ready to go in the upcoming game against what was officially being called the Notre Dame All Stars.

As the Maroons were making their preparations to play the game against the Notre Dame All Stars, Doc Striegel received a call from his nemesis Shep Royle. If Doc thought that the 49–0 drubbing the Maroons gave Royle’s Yellow Jackets was the last he would hear from him for the season, he had another thing coming. Royle was calling to alert Doc to the fact that he was planning on filing an official protest with the league, objecting to the fact that the game against the Notre Dame All-Stars was being played in Philadelphia, at Shibe Park, and that Philadelphia was the “protected territory” of his team. He went on to say that he had already communicated with the league and that he was assured via telegrams, that his protest would be upheld.

Doc was furious. The game with Notre Dame had been agreed to prior to the game with Frankford back in November and it was anticipated that the game would draw a huge crowd and be a big financial win for all involved. He made two arguments to the league when he contacted them the day after Royle’s call. First, was why this concept of a protected territory was suddenly being enforced. Chicago, he pointed out, had two teams in the same city. He also maintained that he had gotten a green light to play the game in Philadelphia during a phone call with Columbus Tigers’ owner Jerry Corcoran, who was filling in for the league president while Carr was in the hospital having his appendix removed. In the end Corcoran denied ever having the conversation with Striegel, and as Royle had predicted, Carr notified the Maroons that if they went ahead with the Notre Dame game that they would be suspended from the NFL.

Doc was locked into the game with Notre Dame and Carr had to know that it would be impossible for him to pull the Maroons out of the game. Doc had to think too, that maybe when push came to shove, if the Maroons could win this game and in doing so call into question the conventional wisdom among football fans, that the college game was real football and that the professional game could not hold a candle to it, that maybe Carr would see what their effort had done for his league and go easy on them. In any event, the game would go on.

While tickets for the Notre Dame game sold briskly in Pottsville, the overall crowd on hand for the game was under 10,000, which was less than expected. In the first quarter both teams had trouble generating much in the way of offense. Each team managed only one first down in the period and both teams had passes intercepted. The offenses picked up their play in the second quarter. The Notre Dame All Stars made five first downs to three for the Maroons in the second quarter.

The Notre Dame game was a frustrating one for Walter French. Lost in the hoopla surrounding the presence of the Four Horsemen, was the fact that three lineman of the 1924 National Champion Notre Dame team, who were called the “Seven Mules,” were also making their presence felt in the game and doing their best to stop Walter’s end runs. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported “Wally French who had so completely been covered by his foes that he failed to get started often slipping on the soaked sod when a clear field loomed ahead was taken out in the final half.”34

At halftime a telegram arrived for Doc Striegel and as the team rested up and strategized for the second half, Doc opened the message from the league office. Joe Carr had followed through on his threat. Because they went ahead with the game in Philadelphia, he was suspending them from the league, cancelled the rubber match they had scheduled for the next day with Providence making it impossible for them to claim the league championship that they had won on the field the week before and to make matters worse he was ruling that they had forfeited their franchise. One can only imagine the feeling in the locker room when Doc shared this news with the team.

Rauch replaced Walter French with Tony Latone at the start of the second half. It was time, he felt, to play some old school Maroons football, what we would call today a “ground and pound” style and see if the Notre Dame team could hold up.

Latone, following the bone crunching blocking of the Maroons’ line and Barney Wentz, moved the ball deep into the Notre Dame territory. With the ball on the 18-yard line, and the Notre Dame defense gearing up for another run by Latone, Ernst took the snap and dropped back to pass and unnoticed, Latone slipped out into the flat and Ernst flipped the ball to him and Latone made the catch and walked into the end zone. Berry uncharacteristically missed the extra point kick and Notre Dame held on to a 7–6 lead.

On the next Notre Dame possession Harry Stuhldreher went back to pass but the Stein brothers and Duke Osborn broke through the line and forced him to rush his attempt, and the Maroons intercepted the pass. Back on offense, the Maroons, using the same strategy that got them their first score moved the ball down field to the Notre Dame five-yard-line where the Notre Dame defense stiffened. On fourth down, the Maroons decided to forgo the field goal and go for the touchdown. Ernst floated a pass to Berry for what looked like a sure touchdown but Charlie had the ball tip off his fingers and fall to the ground.

Undaunted, the Maroons’ defense once again held firm and forced the Notre Dame team to punt the ball back with time running out in the game. Leyden boomed a 60-yard punt backing the Maroons up to their own eight-yard-line.

Notre Dame knew what was coming but was powerless to stop it. Latone ran the ball on five straight plays, Wentz took two carries and then the ball was handed back to Latone who in four carries had the ball to the Notre Dame 21-yard line. Finally, with only seconds left in the game, darkness falling and the ball on the 18-yard-line, Rauch sent Berry to kick the winning field goal. Herb Stein at center snapped the ball to Jack Ernst who caught it and placed it on Berry’s favorite spot, and Berry, grateful for the chance to redeem himself after dropping a sure touchdown earlier, kicked the ball squarely, sending it over and through the uprights.

“Most of the fans at Shibe Park, even the ones from Pottsville, had come out for a fun day of football and a glimpse at the famous Four Horsemen. Instead, they were witness to a watershed moment in the history of American sports: the very moment that professional football surpassed college ball.”35

From here the story of the NFL Championship of 1925 really gets murky. Two days after losing to the Maroons on December 6 the Chicago Cardinals announced that they had scheduled two more games to be played before the December 20 official end of the season. Unaware at that point that the Maroons would be stripped of the title, Chris O’Brien hoped that two wins over weak opponents would mean that the Cardinals would finish the season with the best record and thereby still lay claim to the title. A game was scheduled with the Hammond Pros the following Saturday and the next day they would play the Milwaukee Badgers. There was just one problem. Both of those teams disbanded when their season ended. Milwaukee, in fact, did not have enough players available to field a team when their game kicked off and had actually gone out and recruited high school players to fill out their roster, which was a major violation of the league rules.

O’Brien’s motivation for going through all of these machinations was an attempt to set up a showdown with the Chicago Bears and their star player and world class drawing card Red Grange. However, Grange was injured in his next game and was shut down for the remainder of the season. The Cardinals beat Hammond and Milwaukee but Joe Carr launched an investigation into the use of high school players by Milwaukee. Ultimately the Milwaukee team was not suspended but its owner, Ambrose McGurk was forced to sell the team. Meanwhile Chris O’Brien and the Cardinals were fined $1,000 and put on probation which was essentially a slap on the wrist. Carr determined that O’Brien was not aware of the fact that the Milwaukee team was using high school players even though it was a Cardinal player, Art Folz, who was banned for life for his part in arranging for the schoolboys to join the team.

Never one to give up without a fight, Doc Striegel made one more attempt to change Carr’s mind. He traveled to Columbus to beg the league president to reconsider his decision. The best Carr would agree to would be to bring the matter before the league owners at their next meeting on February 6, 1926. The meeting took place in the Hotel Statler in Detroit. Although Doc was allowed to be in the room for the meeting, Carr alone presented the facts to the owners. In his remarks, Carr once again addressed how important protecting a franchise’s market was to the growth and integrity of the league. He also focused on the fact that “three different notices forbidding the Pottsville club were given and the management elected to play regardless” and in the final analysis this insubordination may have been what rankled him the most.

After the owners gave Doc a chance to present his side, they discussed the matter for 10 minutes and then voted to back Carr. The Maroons were still out of the league. A motion was then made and seconded to award the 1925 Championship to the Cardinals, who on the strength of their win over Hammond had the best record. However, just as the vote was taken, word arrived that the Cardinals’ owner Chris O’Brien, who was not at the meeting, was informing the owners that the Cardinals would not accept the championship under these circumstances, at which point the matter was tabled and the 1925 championship was never awarded to anyone. In 1933, Charles Bidwill, a Chicago businessman, lawyer, and an associate of Al Capone, bought the Cardinals. Bidwill made his fortune as the owner of dog and horse racetracks. To that point in time the Cardinals did not have one title to their name so it is easy to understand why the new Cardinals’ owner could not have helped himself from accepting the 1925 title. It would be the only title the team would win until 1948, one year after Bidwill died of pneumonia.

The story of the 1925 football season and the Pottsville Maroons, however, does not end there. Shortly after the owners meeting where the Maroons were kicked out of the NFL a presentation was made to the owners by Red Grange and his agent Charles C. Pyle. Grange and Pyle told the group that they had reached an agreement to lease Yankee Stadium and planned to put a team in New York. One can just imagine how uncomfortable this must have been for Carr and the owners. Carr had just waxed poetically about the importance of protected territories in his case against the Maroons and the owners had just unanimously agreed with him. Not to mention the fact that Tim Mara, owner of the New York Giants who held the “rights” to the New York market was in the room. However, Grange was by far the sport’s biggest star and everyone wanted him in the fold. Carr and the owners were stuck, they had to back Mara, and stand behind the pronouncement that they had just made regarding protected territories in the Maroons’ case and so they turned down Grange and Pyle.

Undeterred, Grange and Pyle announced that they would form their own league, the American Football League, for the 1926 season and the NFL found itself in a battle with Grange’s league. AFL franchises were started in Boston, Brooklyn, Chicago, Cleveland, Los Angeles, Newark, and Philadelphia, in addition to Grange’s New York entry, the Yankees. The Rock Island Independents were the only NFL team to jump to the new league.

Chris O’Brien and the Chicago Cardinals found themselves faced now with having to compete with two professional teams in Chicago, the Bears and the Bulls in the new league. To help keep the Cardinals solvent, Carr rescinded the $1,000 fine that had been levied against O’Brien for the Milwaukee game. Art Folz’s ban from the league was also rescinded to keep him from playing for the rival league.

This left the Maroons, the best team in football, with no league and a prime target for Grange and Pyle. Remarkably, to keep the Maroons and the credibility they would bring away from the new league, Carr reinstated the Maroons for the 1926 season but there would be no change in the status of the 1925 title.

The cancellation of the planned game against Providence after the Four Horsemen game, although he did not know it at the time, meant that Walter French had played in his last football game on that December 12, 1925. It had been quite an experience. In a couple of months, he would be packing his bags and heading south for spring training with the A’s.

In some telling of the tale of the Maroons and the 1925 season, in an effort to romanticize even more, an already remarkable Cinderella story, Walter French is depicted as “Little Walter” and a puny third stringer. The fact was, however, that Walter had been one of the stars of the team throughout the season. Only playing in nine games he finished the season with five touchdowns. Only Latone, who played in 12 games, and had eight touchdowns, Flanagan, who also played in 12 games and had seven touchdowns, and Berry, who played in 10 games, and finished with six touchdowns, had more than Walter did in 1925. Plus, his scores did not come on one-yard plunges. His touchdowns were long, break away efforts which averaged almost 30 yards each. In a league that had 20 teams in 1925, only nine players, including his three teammates, scored more touchdowns than did Walter French.

At the conclusion of the 1925 season Walter French, whose 5.4 yards per carry led the entire NFL, was named first team All-Pro by two of the recognized selectors at the time, E.G. Brands for Collyer’s Eye, a sports journal published in Chicago and by the Ohio State Journal. He and Charlie Berry were the only two Maroons to be named All-Pro by more than one selector.

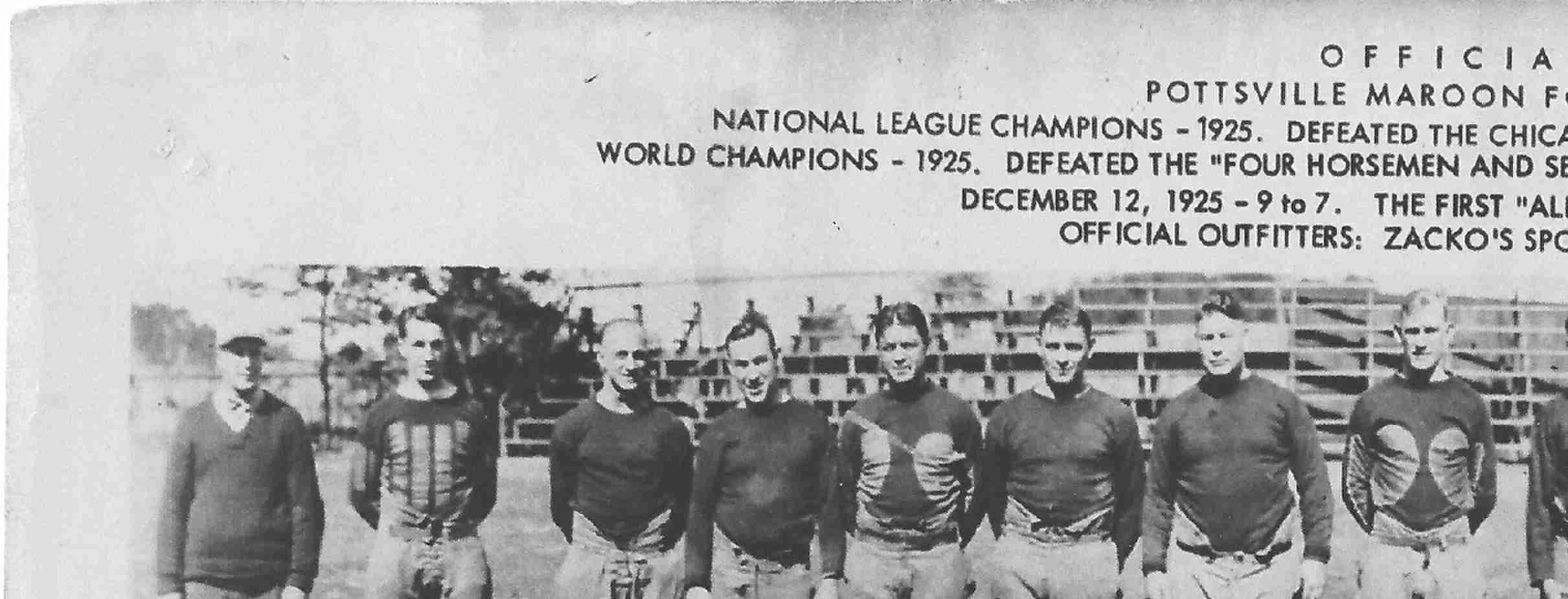

Pottsville Maroons official team photograph, 1925. The Maroons won the professional football title on the field, only to have it stripped by a controversial decision by Commission Carr. (Courtesy of Author)