CHAPTER 8

1929 and the Team that Time Forgot

One would think that adding a big name like Ty Cobb to a team would be plenty for one franchise to handle, but Connie Mack was not done making moves to improve the Athletics. In addition to the “Georgia Peach” he picked up two future Hall of Famers in Zach Wheat, in a trade with the Brooklyn Robins, and the signing of free agent second baseman Eddie Collins. Sportswriter Don Q. Duffy wrote that “seven successive seasons in the American League cellar convinced Mack that the quickest road to the top was experienced material—the more expensive the better … Ponder these three names Tyrus Raymond Cobb, Edward Towbridge Collins and Zachary Davis Wheat. A year ago, they were in other parts, but for 1927 they are members of Connie Mack’s Athletics.”1

The A’s were not the only team making moves, and Cobb, Collins, and Wheat were not the only big names changing teams. It was as if everyone expected that it would take a special team in 1927 to win the pennant and World Series. In the American League the Senators had added Tris Speaker to their team and in the National League the St. Louis Cardinals added 15-year veteran middle infielder Rabbit Maranville to their World Series championship roster. The New York Giants traded future Hall of Famer Frankie Frisch and Jimmy Ring to the Cardinals for their superstar player Rogers Hornsby. Players were not the only new faces on teams, of the 16 managers in major league baseball in 1927, eight were either new to the job or new to their team.

With the addition of Cobb and Wheat, the Athletics went into spring training with five established major league outfielders, plus three additional players Mack had signed from the minor leagues. The holdovers from the 1926 roster were Al Simmons, Bill Lamar, and Walter French. Other new faces in addition to Cobb and Wheat were Dave Barbee, Alex Metzier, and Max West. There was also now a bottleneck in the infield as well. Max Bishop who had been the A’s second baseman was now vying with Eddie Collins for his position, and Chick Galloway the A’s shortstop was now in competition with Joe Boley for whom Mack had purchased from the Baltimore Orioles for $100,000.

It is hard to imagine that Walter did not feel a little threatened by the addition of Cobb and to a lesser extent Wheat, but there is no evidence that he ever mentioned it to anyone in 1927. He had been the team’s second leading hitter in 1926, and his star was on the rise, while Cobb’s best days were behind him. Making it a little easier to swallow for Walter was the fact that his salary had been raised from the $5,000 he earned in the previous season to $7,500 and although it was only one-tenth of what Cobb was being paid, it did represent a sizeable increase.

Another indication that his position was secure was the reaction of Connie Mack to Walter’s request, toward the end of the 1926 season, to once again join the Pottsville Maroons in the National Football League in the offseason. There was no giving in on Mack’s part this time. Walter’s football playing days were over as long as he was a member of the Athletics’ organization. Instead of playing football, in the offseason, Walter took a job as the head coach of the Atlantic City Roses, a team in the professional Eastern Football League.

It also must have made him feel better each day when reading the newspapers because, in their coverage of spring training, the sportswriters were not all convinced that it was a forgone conclusion that the starters from 1926 would not keep their jobs. In an article from March 10, sportswriter Elwood Rigby speculated as to who should bat in the leadoff spot in the lineup: “It is almost a sure bet that Mickey Cochrane will be number one man in the batting order … when either Walter French or Max Bishop are playing, Cochrane no doubt will be moved down the ladder.”2 Adding that “Mack has another exceptionally good boy to put at the top of his batting order in Walter French, who is doomed to see bench duty most of next season because of the acquisition of the great Ty Cobb. French is probably the fastest man on the Athletics’ team. He is a left-handed hitter and gets down to first with amazing speed.”3 Adding an element of uncertainty with respect to the outfielders was the health of Al Simmons. Simmons was a limited participant in the spring training exercises and practice due to a ruptured muscle in his right shoulder.

As spring training progressed to include practice games it became less and less certain that the new acquisitions were better than the players that had been with the A’s in 1926. Davis J. Walsh, Sports Editor for the International News Service, did not pull any punches about what he and others had observed: “Walter French May Beat Ty Cobb for A’s Berth” read the headline. “Neither Ty Cobb nor Eddie Collins will start the season in regular positions with the Philadelphia Athletics unless they can prove they are better men than men now sitting on the bench more or less by courtesy.” Mack, Walsh wrote, “candidly admitted that to date some of last year’s team have looked better.”4

Walsh claimed that Collins’s range had diminished to such an extent that he “can’t cover more than a quarter of an inch around second and Cobb has not been hitting.” “I paid a lot of money to build up the team this year,” Mack told Walsh, “But if my 1926 men prove to be better players, they will get the call regardless of box office values.”5 Both Cobb and Collins assured the A’s fans that they would be ready to go when the season started.

Also not so sure about Cobb was syndicated columnist Billy Evans. “How valuable will Ty Cobb be to the Philadelphia Athletics this year?” he wrote. “My answer is going to be a rather negative one … Ty Cobb has lost much of his speed. I don’t believe that even Ty would give you an argument, if you insisted that he had dropped at least two steps in going to first in comparison to his best days.”6 In addition to losing a step on the bases, Evans also pointed to another deficiency in Cobb’s game, “Cobb can no longer get the quick start on a fly ball that was once his custom, neither can he cover the wide territory that he could when in his prime.”7

As opening day rolled around it seemed that all of Connie Mack’s pronouncements that when filling out his lineup, he would make his decision without concern for “box office value” seemed to ring hollow. In the season opener against the Yankees on April 12 a record-breaking crowd of 65,000 fans packed Yankee Stadium to see the league’s top pennant contenders. When Mack posted his lineup Max Bishop was on the bench in favor of Eddie Collins at second, Chick Galloway sat while the newly acquired Joe Boley started at shortstop, and Ty Cobb started in right field while Walter French sat the bench.

Mack selected Lefty Grove as the starting pitcher who was opposed by Yankee ace Waite Hoyt. Both pitchers looked sharp and the game was a scoreless tie until the bottom half of the fifth inning when the Yankees broke the game open by scoring four runs helped by A’s fielding errors by Mack’s new men Collins and Boley.

In the top of the sixth Ty Cobb beat out a bunt flashing some of his old speed. He then advanced to third on a single by Sammy Hale and he scored on a fielder’s choice. The A’s scored one more run in the sixth to make it a 4–2 game. The Yankees however, put four more runs on the board in the bottom of the sixth inning to finish the scoring. In the ninth inning Walter French was put into the game to hit for Joe Boley and failed to reach base.

The next day was more of the same for the A’s as they lost to the Yankees by a score of 10–4. In this game, Babe Ruth, who was removed from the first game due to illness, came back with a vengeance going two for four with a triple and two runs scored. Cobb had another productive day going two for four with one run scored.

In the third game of the season the two teams combined for 26 hits and 18 runs but the game ended in a 9–9 tie, when the game had to be called for darkness.

In the final game of the series the Yankees once again handed the A’s a beating, this time by a score of 6–3. In the first inning Babe Ruth brought the crowd to their feet when he hit his first home run of the season. There would be more where that came from this season.

Walter French went into the final game of the Yankee series as a pinch runner and came around and scored his first run of the season. It is not hard to imagine what was going through his head as the first few weeks of the season were being played. His expectations for the 1927 season had to have been high given his success in 1926. In the first month of the season however, he saw very limited action, used exclusively as a pinch hitter, pinch runner, and occasional late inning defensive replacement for Ty Cobb. Making matters worse was the fact that the three men who were emerging as the regular outfielders had all started the season very hot at the plate. In the first week of May, leftfielder Bill Lamar was hitting .357, Al Simmons in centerfield was hitting .410 and Ty Cobb in Walter’s rightfield position was hitting .409.

On May 5, the A’s were in second place with a record of 11–7, only one-half game behind the first place Yankees who were sporting a record of 12–7. The A’s faced off against the last place Red Sox at Shibe Park. With the Red Sox trailing 2–1 in the eighth inning Ira Flagstead hit a pinch hit, two-run home run to give the visiting team a 3–2 victory. But the lead story of this game was not the dramatic outcome. In the eighth inning Cobb crushed a pitch high and far into right field. The ball was hit so high that the Boston Globe reported that it went over the housetops on 20th Street. Umpire Red Ormsby called the ball foul. Cobb and Al Simmons, who was in the on-deck circle when Cobb hit the ball, rushed the umpire screaming their disapproval. The argument went on for 10 minutes and then Ormsby ejected Simmons. At this point Cobb made some comments to Ormsby and he was ejected from the game as well. However, Cobb refused to leave the field and then grabbed Ormsby and began shaking him. It was not until A’s coach Kid Gleason subdued him did Cobb leave the field.

Upon learning about the incident in Philadelphia, American League president Ban Johnson suspended Simmons and Cobb “indefinitely” and both men were out of the lineup when the A’s played the Cleveland Indians at Dunn field the next day. Instead, Connie Mack had Bill Lamar in left field, Zach Wheat in right field and starting for the first time in 1927, Walter French in center field. He had one hit in five at-bats, with an RBI. He also made a good play in the outfield throwing out George Burns, who was attempting to go from first to third on a single. Cleveland however won the game 11–10.

Cobb and Simmons were also out of the lineup in the second game of the series with Cleveland, another loss for the A’s, this time by a score of 4–2. Once again batting in the leadoff spot for the A’s Walter French had two hits, a single and a double, in three official at-bats, along with one walk. The two A’s stars were still not in the lineup when the team faced Cleveland for the final game of the series, yet another loss, this time by a score of 6–1. Walter French once again was in the leadoff spot in the lineup and playing centerfield. He went hitless in three plate appearances.

At this point in the season the Athletics had a record of 11–10 and had dropped into fifth place in the American League but were still only 2.5 games behind the first place Yankees who were 14–8.

The next game for the A’s was one of the most anticipated games of the 1927 regular season. It would mark Ty Cobb’s return to the city of Detroit and Navin Field. There was only one problem, both he and Simmons were still suspended for their actions in the game against the Red Sox.

The timing of the suspension of Simmons and Cobb just days before the big series in Detroit was not good for Walter and his chances for more playing time. Clearly Ban Johnson, still fuming about being overruled in the Dutch Leonard Affair, was looking to throw the book at both players over the ruckus they caused in Boston, by suspending them indefinitely. However, pressure began building on Johnson to reverse himself or at least end the suspension at three games, which would allow Cobb to play in Detroit. Leading the protest was Connie Mack who argued that Ormsby, realizing that he had made a bad call, apologized to Cobb. “I want Ormsby to explain why he apologized to Ty for putting him out of the game and then made a report to Ban Johnson that apparently inflamed him,”8 Mack wrote. Hundreds of telegrams came into the league office, mostly from Detroit where the Tigers had planned a full day of festivities honoring Cobb. Finally, Johnson got a last-minute report from the second umpire working the game in Boston, Brick Owens, in which he claimed that he never saw Cobb strike Ormsby. Ultimately Johnson issued a last-minute reprieve saying, “I do not see how I can keep Cobb out of the game any longer considering Owens’ report.” Simmons was also reinstated but Johnson did require that each player be fined $200 “payable by personal check within forty-eight hours.”9

Ban Johnson’s reversal was joyously received in Detroit where the largest weekday crowd, nearly 30,000 strong, in the history of Navin Field, prepared to celebrate Cobb’s return. Both Simmons and Cobb were eligible to play in the game. James Isaminger writing in the Philadelphia Inquirer described the scene this way: “Probably no other player in baseball history was as regally honored as was the Dixie Daredevil, who was the lion of the city of automobiles from 1905 to 1926, came back today in his twenty-third season of high-pressure baseball, still the acclaimed monarch of the American League attack and wearing the regalia other than Detroit’s for the first time in his career overlapping two long decades.” Cobb was given a testimonial luncheon, a “high grade” automobile, a chest of silver, a big cowboy sombrero, and a floral piece shaped like a huge corncob.10

The game, which seemed like an afterthought to the crowd on hand that day, was won by the Athletics by a score of 6–3. Walter French, although not in the starting lineup, was sent up to hit for Cobb in the eighth inning and stayed in the game to play right field. In his one at bat, he hit a two-out single which scored Eddie Collins and moved Bill Lamar to third. Al Simmons then drove both men in with a double that put the game on ice.

For the remainder of the month of May, Walter French was relegated to entering the game as a late inning defensive replacement for Cobb. In some of the games he would get one at-bat but nothing more. It didn’t help that all three of the men playing ahead of him were still among the league’s leading hitters. On May 31, Cobb was hitting .381, Bill Lamar .337, and Al Simmons was hitting .399. At this point in the season the A’s were in third place with a record of 22–20, and six games behind the first place Yankees who had a record of 28–14. In second place were the Chicago White Sox with a record of 27–17.

Although he was the leading pinch hitter in the American League in 1925, Walter had shown in the last month of that season and again in 1926 that when used regularly he could be a very effective offensive player. But with so few opportunities to hit at this stage of the season, his batting average dipped to .174. He played in only four games from May 31 to June 18. In one he went in as a pinch runner and the other three as a defensive replacement for Cobb. He only came to bat three times over that span.

Finally, coming into a double header at Shibe Park against the Washington Senators, after Cobb landed himself on the injured list with a strained side, Walter was inserted into the starting lineup for both games. He was batting second and playing right field. The game got off to a rough start for Walter when his throw to the plate sailed over the head of Mickey Cochrane, allowing Goose Goslin of the Senators to score an unearned run in the top of the first inning. However, he made up for his miscue by hitting the ball in both games, as the Philadelphia Inquirer reported “French atoned for his sinful conduct by belting the ball hard in both games. He had two singles in the first game and a single and a triple in the second. The long lick scoring two runs and taking all of the fight out of Washington.”11

Pitching in the second game for the Senators was Walter Johnson. Johnson was pitching in the final season of his illustrious Hall of Fame career. It would be the last time that Walter French would square off against the “Big Train.” His two hits brought his lifetime average against one of the greatest pitchers in the history of baseball to .381.

The following day, with Cobb still nursing his injury, Walter started both games of a second doubleheader against the Senators and went hitless. He played the whole game the next day and again went 0 for 4.

Next on the schedule for the Athletics was a series against the New York Yankees. At this juncture of the season, not even the halfway point, it was becoming obvious that the Yankees were in the process of putting together an historic run. They sat atop of the American League with a record of 44–17, a full 10 games ahead of the A’s who had worked their way back into a virtual tie with the White Sox for second place. Head-to-head games between the two teams would be crucial if Mack’s team was to have any chance at catching the Yankees.

On June 25 the two teams squared off in a double header, necessitated by a game having been postponed in May due to rain. There were over 50,000 fans in attendance at Yankee Stadium. In what James Isaminger described in the Philadelphia Inquirer as “their boldest stroke of the year”12 the Athletics swept both games from the Yankees. The first game by a score of 7–6 and the second game by a score of 4–2. Walter started both games and had one hit in three tries in the first game, with a successful sacrifice thrown in and one hit in four at-bats in the second game. In both games he came around and scored a run. Spirits were lifted in Philadelphia. “The Athletics seemed to serve notice,” Isaminger noted “that there will be a keen pennant fight in the American League after all and with the halfway mark in the race not quite reached there will be plenty of chances to overhaul the gifted bat bearers of the Yank cast in the last half of the race.”13

On the following day another sellout crowd was on hand for another double header. In the first game, Walter French collected three hits in five at-bats and scored two runs as the A’s took their third straight game from the Yankees. The Yankees bounced back in the second game winning by a score of 7–3 on the strength of Lou Gehrig’s twenty-second home run of the season. Slowly but surely, Walter’s batting average was starting to rise after he collected one more hit in the second game. In the eight games that he had started since Cobb’s injury, he had hit safely in six of the games, collecting nine hits in total.

Unfortunately, the A’s still had two more games to play against the Yankees before the series would be over. The Yankees won the first game by score of 6–2 and the next day they won by a score of 9–8. The Yankees had come back and despite the fact that they had won the first three games, the A’s were essentially right back where they started when the series began, 10 games out of first place. Walter was hitless in the first game but bounced back the next day going two for four.

On July 2, Cobb returned to the starting lineup and Walter was relegated to pinch hitting once again, coming to the plate only two times over the next nine games. Finally, on July 11 he was inserted into the lineup replacing Bill Lamar in left field. He responded with one hit in four trips to the plate and the Athletics defeated the St. Louis Browns by a score of 7–6. He remained in the lineup the next day against the White Sox in Chicago, collecting three hits and scoring one run in an 8–5 A’s loss. However, except for one appearance as a late inning defensive replacement for Zach Wheat, he was relegated to the bench again until July 21. On that day he played left field and hit in the seventh spot in the order. He had one hit and scored two runs as the A’s defeated Cleveland 8–3 and he played long enough in the next game to come to bat twice, although he went hitless.

At this point in the season the Athletics were mired in fourth place in the American League, already 18 games behind the Yankees, when they lost their best player and the leading hitter in the American League, Al Simmons. The Associated Press reported that “Simmons injured his groin sliding into second base” and that “physicians had advised him today to remain inactive until the middle of August. Manager Connie Mack switched Ty Cobb to center field, placed Zach Wheat in left and Walter French in right against Detroit as a result of Simmons’ absence.”14

Walter responded with one of his best games since joining the Athletics. He finished the game, a dramatic 13-inning affair, with four hits in five trips to the plate. He also scored a run and had one run batted in. With the A’s trailing by one run in the bottom of the ninth inning Walter led off with a long double. Eddie Collins came up as a pinch hitter for Boley and laid down a perfect sacrifice bunt which sent him to third base. Bill Lamar followed with a single, scoring Walter with the tying run. In the thirteenth inning Jimmy Dykes won the game with a walk off home run.

The Tigers bounced back the next day in the first game of a doubleheader, with a 10–4 win. In this game Walter French, again batting seventh and playing left field had three hits in four at-bats and scored one run. In the second game he went two for three including a triple, with four runs batted in, two with two outs, as the A’s won 5–2. He had also raised his batting average, once as low as .174, to .288.

As the calendar switched over to August, Walter had to be pleased about the turn of events that gave him the opportunity to play every day. In the seven games that he had played since Simmons’ injury he had nine hits. Meanwhile the Yankees were running away with the American League with a record of 73–28. They were followed by the Washington Senators and Detroit Tigers, with the Athletics still stuck in fourth place.

Next on the schedule for the A’s was a series at Shibe Park against the Yankees on August 9. By this point Walter had expected to see his name on the manager’s lineup card each day but he was not ready for what he saw on this day. No longer was he hitting seventh in the A’s lineup. Connie Mack had moved him up to the third spot in the order just ahead of Ty Cobb and Mickey Cochrane. So, the three, four, and five hitters for the Athletics, considered the meat of any team’s batting order, were Walter French, Ty Cobb, and Mickey Cochrane respectively. The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that “Mr. Mack promoted Fritz French to third place in the batting order and the young Jersey lightning showed his appreciation by smashing out two singles and a double.”15 Hitting third he went three for five, with two runs scored and two runs batted in as the A’s drubbed the Yankees by a score of 8–1.

Still hitting in the third spot in the lineup the next day against the Red Sox, Walter collected two more hits, scored three times, and knocked in two runs as the A’s won by a score of 12–2. As designed, the three, four, and five hitters for Philadelphia, French, Cobb, and Cochrane, drove in eight of the team’s 12 runs.

Walter stayed hot the next day, August 11, with two hits in four at-bats with a run scored to back up the pitching of Howard Ehmke who shutout his former team, Boston, 4–0 in the first game of a doubleheader.

After the second game, which the Red Sox won by a score of 2–0, Walter along with Mickey Cochrane and Jimmy Dykes were transported to the town of Catasauqua, PA, a suburb of Allentown located in Lehigh County. The occasion was the town’s annual carnival. The players were expected to meet with fans, sign autographs, and participate in some of the different activities.

Originally, Ty Cobb was supposed to attend with Dykes and Cochrane but he was a last-minute cancellation and Walter was tabbed to go in his place. Walter said he would be happy to do it as long as he was able to get back to Philadelphia in time to catch the last bus to Moorestown, NJ where he lived with his wife, who was pregnant at the time, and his daughter Fran. George Bellis, who was one of the organizers of the event and who was driving the players back to Philadelphia, promised Walter that if he did not get him back to catch the last bus at midnight, he would drive him the rest of the way, a trip of about 15 miles. One of the featured events at the carnival was a dog show, specifically for bird dogs used by hunters and Walter performed as the judge of the contest. One can only surmise that Cobb, a legendary hunting enthusiast, was originally supposed to serve in this role, and given that Walter was filling in for Cobb, he was enlisted as the judge, despite how little he knew about the subject.

As Walter expected, Bellis did not leave Catasauqua with the players until 11 o’clock. Even today one would be hard pressed to make the trip to Philadelphia from Catasauqua, a distance of about 65 miles, in an hour. After dropping Dykes and Cochrane off in the city, true to his word, Bellis started driving Walter to his home in Moorestown.

When they were about halfway, in the town of Merchantville, NJ, they came upon the bus that Walter was supposed to be on. It had been involved in an accident with two of its occupants injured. Witnesses said that a speeding touring car had cut off the bus attempting to squeeze between the bus and a trolley car. The bus driver, credited with preventing an even worse outcome, took evasive action, maneuvered his bus over the sidewalk, having it come to rest in the front yard of the home of former Congressman Francis Patterson. The driver of the car was charged with reckless driving. According to a newspaper account of the incident “French turned to Bellis and said, ‘I’m glad you kept me at Catasauqua as late as you did, or I would have been in that bus.’”16

However, if the late night or the close call bothered Walter French, you could not tell by his performance in the game the next day, where he had two hits in five at-bats and one run batted in. It was much the same in the final game of the series the next day when he led the A’s with three hits and three runs batted in.

The following day against visiting Cleveland he had one hit in five at-bats but that hit resulted in knocking in a run with two outs. In the second game of that day’s doubleheader he led the A’s offense going two for five with three runs batted in. In fact, French, Cobb and pitcher Jack Quinn drove in all of the eight runs that the team scored in their 8–0 victory.

On August 17, Walter had two hits in four trips to the plate and raised his batting average to .302. In addition, the A’s were starting to win a higher percentage of their games than at any other time of the season. No one was going to challenge the Yankees but a second-place finish and the bonus money that went with it, which seemed unlikely earlier, was now within reach.

The Athletics stumbled the following day, losing 2–1 to Cleveland, but Walter remained hot with two hits in four at-bats. Next for the A’s were the White Sox and Philadelphia got off to a fast start. In the first inning Max Bishop led off with a single. He then advanced to second when Sammy Hale grounded out. Walter French then smacked a single and drove in Bishop with the game’s first run. Ty Cobb then singled moving French to second. This brought up Mickey Cochrane, who hit a pop ball in foul territory along the third base line, which was dropped by the White Sox third baseman Willie Kamm giving Cochrane new life. Mickey then hit the next pitch over the right field wall for a three-run home run, scoring Walter and Ty Cobb ahead of him.

On August 25, French, with three hits in four at-bats, Cobb, who had five hits in five chances, and Cochrane, who had two hits in five trips to the plate accounted for 10 of the 14 hits the A’s had in a 6–1 win over St. Louis. Walter’s batting average was now at .317. Moreover, the A’s were quietly putting together a winning streak and had moved into third place only 1.5 games behind the second place Detroit Tigers. The A’s won again on August 26 beating St. Louis 7–0 and again Walter had three hits, and in what was becoming a regular occurrence scored one run and knocked in another.

On August 28, in a crucial head-to-head matchup with the Detroit Tigers, Walter led the way to a key A’s victory with three hits all of which resulted in him coming around to score in a 9–5 win.

As August came to an end, the Athletics had finally moved into second place and were now three games ahead of the third-place Tigers. While the difference between second and third place to a modern-day baseball fan, in an era with playoffs and Wild Card teams, may not seem significant, it meant a great deal financially to the teams involved. The A’s had 21 wins against only seven losses in the month of August, and since moving Walter French to the third spot in the lineup on August 9, they had gone 17–4 for the rest of the month of August, an almost identical record to that of the Yankees over the same span. No one on the A’s was more instrumental in putting this run together than was Walter French.

However, if the A’s were feeling pretty good about themselves, the Yankees put that right in the first game of September by beating them at home by a score of 12–2. Babe Ruth hit his forty-fourth home run and Lou Gehrig hit two, his forty-second and forty-third. Walter French still continued to perform well, getting one of the only six hits the A’s got off of Yankee Ace Waite Hoyt.

The next day Lefty Grove blanked the Yankees by a score of 1–0, holding “Murderers’ Row” to only four hits.

On September 6, a familiar name was back in the Athletics’ lineup. Walter started the game as had been the case for almost a month, batting third and playing right field, but after he came to bat twice, Al Simmons was sent in to replace him in the first game of a double header that was won by the Washington Senators. Walter was back, however, for the second game and went two for four as the A’s took the Senators behind the pitching of Eddie Rommel by a score of 4–0.

The following day, September 7, the A’s had an exhibition game against a team in Allentown, PA. Playing these exhibition games during the season was not an unusual occurrence for the A’s. The Philadelphia Inquirer noted that “Connie Mack had booked another one of his hoodoo exhibition games.”17 Earlier in the year Ty Cobb had been injured in one such game in Buffalo, NY. Pitching for the Allentown team was “Beezer” Stauffer, a local baseball legend. With Al Simmons, just back in the lineup the day before at the plate, “Beezer” tossed up one of his slow, tantalizing curve balls at which Simmons took a mighty cut and came up with nothing but air, and in the process twisted his ankle. He stayed in the game but he was not in the lineup when the Athletics squared off the next day against the Tigers. The A’s won the game easily by a score of 9–1. Walter was back in his normal spot in the lineup and had one hit and one run scored.

Walter continued his excellent play, the Athletics continued to win, and Al Simmons still had not been near the field since his mishap in Allentown. Finally on September 14, Simmons went in and played left field late in the game that the A’s won 5–4 against the White Sox. In that game Walter had two hits in five at-bats and came around to score twice. By this juncture of the season Connie Mack’s team was secure in second place with a seven-game lead over the Detroit Tigers.

Finally on September 15, Al Simmons was put into the starting lineup, only as the left fielder, Walter French continued to start in right field and despite the presence of Simmons who was hitting nearly .400 at the time of his injury, continued to bat third in the A’s lineup. Simmons had one hit in the game, Walter French had two.

Slowly but surely, Simmons began to regain his form. On September 19 he had three hits, including his fifteenth home run of the season, and he knocked in three runs bringing his season total to 105 as the A’s defeated the St. Louis Browns by a score of 4–1.

When the Athletics beat the Browns again the next day by a score of 7–3, both Simmons and French went two for four and each man scored a run.

On September 22, Walter French for the first time since Simmons injury was not in the A’s lineup when they faced the Cleveland Indians in a game won by Philadelphia by a score of 4–3. He was back in the lineup a few days later, no longer hitting third but down in the lineup hitting seventh. A new name appeared in the box score for the Athletics, catcher Jimmie Foxx, who Mack was converting to a first baseman, in an effort to get both his bat and that of Mickey Cochrane into the everyday lineup.

On September 27, Walter had one hit with one run batted in, in a 7–4 loss to the Yankees. In that game Babe Ruth hit his fifty-seventh home run, a three-run shot off of Lefty Grove.

As the 1927 season came to an end, Connie Mack, like all of his contemporaries in the American League, was already pondering what moves he would have to make to keep up with the Yankees. One wonders if one of the options he considered was keeping Walter French in the regular lineup. In the 52 games he started from August 2 through the end of the season, Walter batted .325. In that stretch he had 21 multiple hit games and overall played outstanding defense. More importantly the Athletics won 40 games against 16 losses. A closer look at the 40 games played from August 9, when Mack moved Walter to the third spot in the order through September 21, his last game hitting third, the Athletics went 31–9, which was even a better record than the Yankees over the same span.

As bad as the season had started for Walter French, he had to feel pretty good about the way it ended and his prospects for the 1928 season. Most observers believed it to be unlikely that Cobb would return for his twenty-fourth season. He would be 41 years old in 1928. There was even some speculation that Connie Mack, who would turn 66 years old in the offseason, may retire. “Late in the season,” Norman Macht wrote in his biography of Mack “everywhere the Athletics went the writers renewed the speculation about Connie Mack’s retiring. The presence of Eddie Collins a logical successor, fertilized the guesswork.”18

The Journal Gazette of Mattoon Illinois reported that “the chance to become a sure enough big leaguer has apparently caused Walter French of the Philadelphia Athletics to cut down on professional football. I note where he has signed to assist in coaching football at Swarthmore … now with a chance to become a major league star, French has decided the chances taken in football are not in keeping with the possibilities offered in baseball.”19

Confident that he would find himself as one of the regular outfielders in 1928 Walter headed off to his offseason job coaching football at Swarthmore College under head coach Roy Mercer. Mercer was a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania, who was a star on the football and track teams. He was a member of two U.S. Olympic Teams, 1908 and 1912. He earned his MD at the University in 1913 and served on the staff of two Philadelphia hospitals, while coaching football at the same time. In 1955, he was elected to the College Football Hall of Fame.

Even though the A’s 1927 season ended on a high note and with a second-place finish, there was little cause for celebration. The A’s had won 91 games and still finished an amazing 19 games behind the eventual World Series champions Yankees. If the 1926 season had not convinced everyone that the game had gone through a cosmic change, the 1927 season brought the message home in a brutal fashion. The 1927 Yankees completely dominated their competition, and for Connie Mack the message was clear, the game of baseball had changed and he and his team needed to change with it. The Yankees had outscored the A’s by 135 runs even though the teams had an almost identical team batting average. During the season the Athletics, as a team, hit 56 home runs, compared to 158 for the Yankees. Babe Ruth alone had 60 and Lou Gehrig finished the season with 43 home runs and 175 runs batted in. Al Simmons, the Athletics’ leading home run hitter, had a total of 15 by comparison. After his team lost both games of a double header to the Yankees by identical scores of 21–0, Joe Judge, first baseman for the Washington Senators spoke for a lot of the American League when he observed “those fellows not only beat you, but they tear your hearts out.”

The Yankees domination also drove down attendance at Shibe Park. Although finishing in second place meant a lot financially to the A’s players, being so far out of first place for all but the very start of the season badly hurt attendance. In 1926, when the team finished in third place, 714,508 people attended games at Shibe Park, the second-best attendance in the league. In 1927 however, finishing second only attracted 605,529 a drop of 108,979 fans which represented only the fourth best attendance in the American League.

One of the rumors that was floating around in early October was that there were two trades in the works, one with the White Sox and one with the Senators. The first trade would have the White Sox sending Bib Falk and Johnny Mostil to the Athletics for Al Simmons. The second called for the Senators to trade Goose Goslin to the Athletics in exchange for Bill Lamar and Walter French. Both rumors turned out to be false and Tom Shibe issued a statement denying any knowledge of a trade being considered involving any of the three members of the Athletics. However, while there was no truth to the rumor that Mack planned to trade for Falk, Mostil, and Goslin, on December 27, Mack made the first of what would be a number of offseason moves in an effort to keep up with the Yankees. Bing Miller, with whom he had parted in 1926, as Walter French developed into a dependable everyday player, had had a good season in 1926, batting .326 after arriving with the St. Louis Browns and he followed it up in 1927 by hitting .319 and knocking in 75 runs in the process. When the Browns indicated that they were prepared to accept pitcher Sammy Gray, who had a respectable 9–7 record for the A’s in 1927, in a trade, Mack jumped at the chance to bring Miller back to Philadelphia.

Then on February 1, 1928, the Washington Senators announced that they were releasing Tris Speaker. For most outside observers it appeared to be the end of the road for the 40-year-old star. He was not alone. In fact, a number of sports stars who had come to prominence in the decade of the 1920s had either announced their intention to retire or were expected to do so soon. Famed sportswriter Carl Finke, from Dayton, OH in his weekly column “Finke Thinks” wrote that the winter of 1927–28 would go down as the “most retiring in all history of sport.” He went on to cite the announced retirements of Walter Johnson, boxing great Jack Dempsey, U.S. Polo team captain Devereux Milburn, tennis great Bill Johnston, and Tad Jones longtime head football coach at Yale before finally adding “Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker apparently are through with the big show.”20 On February 5, The Sioux City Journal added “The expected passing of Tris Speaker from the major leagues will mark also the exit of the greatest fly chaser in baseball.”21

That same day however, unbeknownst to the sportswriters, Connie Mack interrupted his Florida golfing trip to place a call to Speaker with an offer of $15,000 to join the Athletics, an offer the 40-year-old accepted.

When Ty Cobb ultimately did retire after the 1928 season he was asked if he had any regrets looking back on his 24-year career. The only regret he would acknowledge was that he hadn’t played his entire career with the A’s and Connie Mack. In his Mack biography Norman Macht wrote that “Ty Cobb’s admiration for Connie Mack was genuine. Watching him manage men on a daily basis, Cobb recognized in Mack what he himself had lacked as a manager.”22 Grantland Rice once ask Ty how he would rate Connie Mack as a manager and as a man. Cobb replied that Mack was “about the best I have ever known. He is smart and square. He understands baseball and men … the ballplayer who won’t work his head off for Connie Mack isn’t much good.”23 And so it was that Connie Mack was able to prevail upon Ty to put off his retirement for one more year.

Before he joined the Athletics the word was that Ty Cobb was a difficult teammate. However, the A’s players who had gone up against Cobb, seemed happy to have him. Jimmy Dykes, himself a hard-nosed player, recalled with a smile how when he first broke into the major leagues and was playing second base, whenever he passed him on the field, Cobb would say to Jimmy “you stink.” Dykes had a tremendous amount of respect for Cobb. Cobb had been the hero of some of the younger players on the A’s like Max Bishop, who told Bill Dooly, “Ty was my big hero … I read everything I could lay my hands on about him.”24 Bishop, a natural right hander, learned to bat lefty because Cobb hit left-handed. Al Simmons benefited from Cobb’s guidance, especially when it came to hitting tough left-handed pitchers. Cobb was known to offer stock tips to players usually recommending that they buy stock in Coca-Cola and those that listened to him were glad they did. Cobb and Mickey Cochrane became particularly close and lifelong friends.

Numbered among the A’s that got along well with Ty Cobb was Walter French. Walter’s daughter Fran recalled meeting Cobb when she visited her father while he was playing for the A’s and how he let her sit on his lap. Walter was also one of the A’s that followed Cobb’s stock tips and purchased shares of Coca-Cola. He and Cobb would be seen together in the clubhouse or on the field before a game. Ballpark errand boy Jim Morrow told how Cobb, Grove, and French would sit in the right field corner bullpen and send him for ice cream or a candy bar and “never give me the money to pay for it and they would holler, don’t let Mr. Mack see you.”25

On February 27, James Isaminger reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer that “in all probability Ty Cobb will announce in a few days that he will play another season with the Athletics. Connie Mack talked to the Peach in Augusta, GA over the long-distance phone tonight and at the end of the conversation he told reporters that Cobb wanted a day or two to discuss the Athletics’ offer with his family.” Mack, however, declared that negotiations were proceeding satisfactorily and that he expected Ty to sign a 1928 contract. Three days later it became official. Ty Cobb had signed with the A’s for the 1928 season. “It took a long campaign to get Ty for another season,” Mack said. “He had virtually retired from baseball and didn’t want to play, but I showed him how useful he would be to me next season and moreover give us a chance for the pennant and he finally relented.” Then Mack spoke the words Walter French must have expected but still dreaded hearing “Cobb, Speaker and Simmons! What an outfield that will be to electrify the nation.”26

The final straw came a few days later when it was announced that Mack had signed first baseman and outfielder Mule Haas who had played for the Pittsburgh Pirates’ organization. Haas was the perfect fit for the type of team Mack felt he needed to compete with the Yankees, a big, strong, powerful hitter.

However, “electrifying the nation” would have to wait because when Al Simmons showed up at spring training in Fort Myers he was “crippled with rheumatism” and “could hardly walk.” Mack suggested that he could be out of the lineup until summer or perhaps all year. When the team travelled north to start the season, instead of suiting up, Simmons was admitted to the Methodist Hospital in Philadelphia.

A crowd of 25,000 were on hand at Shibe Park for the Athletics’ opening day game against the New York Yankees on April 11. The outfield for the Athletics consisted of Ty Cobb in right field, Tris Speaker in centerfield, and Bing Miller, filling in for Simmons, playing left field. The Yankees behind Ruth and Gehrig picked right up where they had left off the previous year as they easily defeated the A’s by a score of 8–3. The next day was more of the same as the Yankees once again beat the home team by a score of 8–7. Walter French went hitless in his one at bat as a pinch hitter while Cobb, Speaker and Miller once again played the outfield. The A’s then lost their next two games to the Senators and once again got the season off to a slow start.

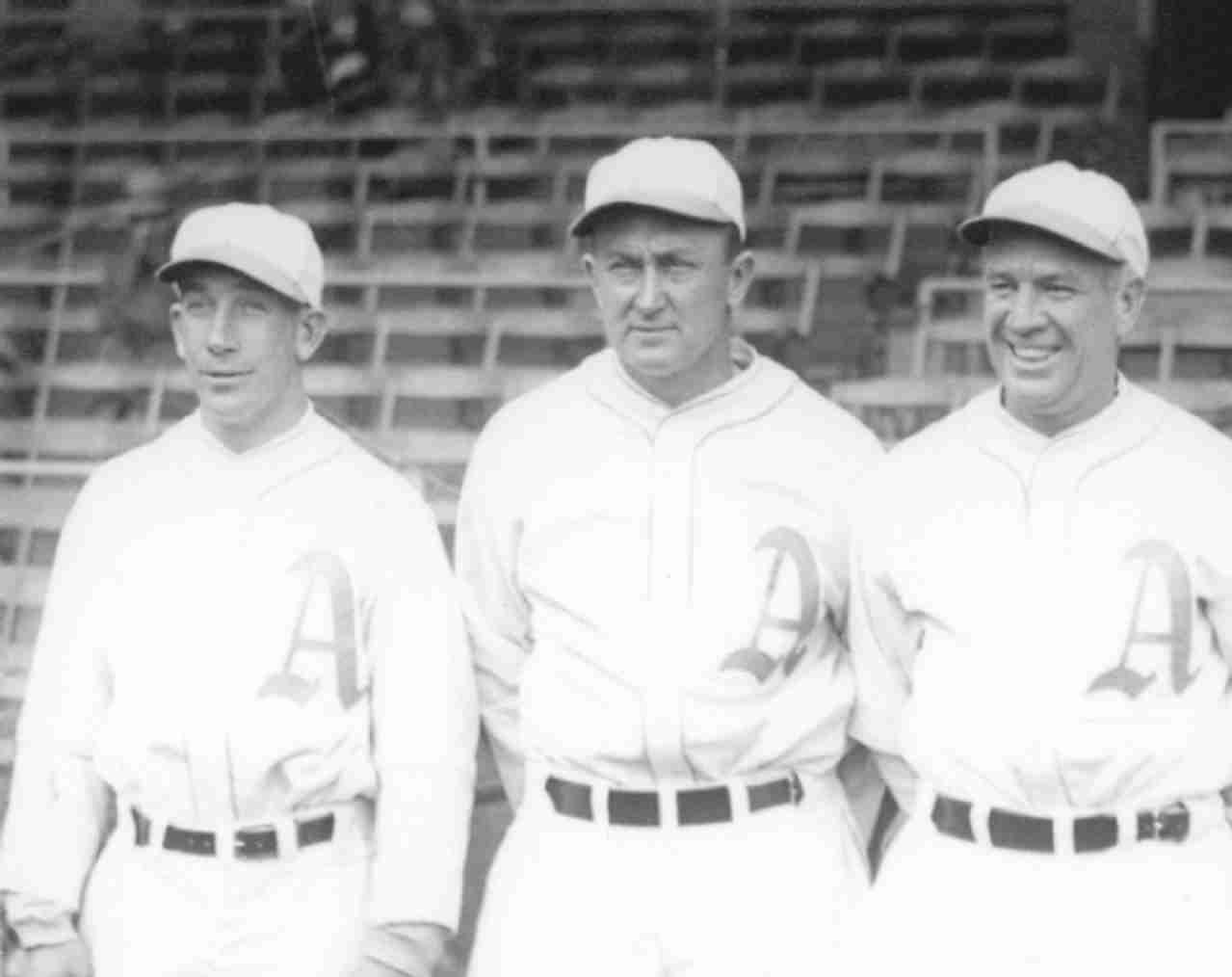

Members of the 1928 Philadelphia Athletics outfield. Left to right: Walter French, Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, Bing Miller, and Mule Haas. Missing from the photo is Al Simmons. (Courtesy of Author)

Over the next few weeks, the team ran into some bad weather and were way behind the other teams in the American League in terms of the number of games they had played. Of the six games they were able to get in, they won each of them and as the calendar flipped over to May, the Yankees were in first with a record of 10–3, followed by Cleveland at 12–6, St. Louis was in third place at 11–8, and the A’s at 6–4 were in fourth place. For his part, Walter French had only made the one pinch hit appearance in the entire month of April.

After going winless in their first four games, however the A’s got hot and by the middle of the month of May they had a record of 16–7 and were in second place 2.5 games behind the Yankees who were 21–5. Mack continued to stick with the outfield of Cobb, Speaker, and Miller. His pinch-hit appearance in the second game of the year was still the only time that Walter did not spend on the bench.

Then on May 21, in the sixth inning of the first game of a double header between the Athletics and the Washington Senators, Bobby Reeves, the Senators’ shortstop hit a fly ball into the gap between left and center. Bing Miller and Tris Speaker both went for the ball and collided just as Miller was about to catch the ball, sending both men sprawling in the ground. Speaker was knocked unconscious and Miller sustained what looked to be a serious injury to his shoulder. Walter French was sent in to replace Miller and Mule Haas went in for Speaker. Haas had three plate appearances, going hitless in two at-bats, and reaching on a base on balls. Walter came up four times, knocking out two hits, one of which drove in a run in the A’s 4–3 win.

In the second game of the doubleheader, with the A’s clinging to a 1–0 lead in the fourth inning, courtesy of a Jimmy Dykes home run, Walter French came to bat with two outs and smacked out a double scoring first baseman Joe Hauser with what would prove to be the winning run. Later in the game his perfect throw from right field beat Senators’ pitcher Bump Hadley to the plate saving another run. The 2–1 victory meant the doubleheader sweep allowed Mack’s team to stay only 3.5 games behind the first place Yankees. The next day Walter was back in the starting lineup and again had two hits in five at-bats, scoring one run in the process.

Next on the schedule for the A’s was a doubleheader against the Yankees. The first game was a makeup of a game from April that was postponed due to extremely cold weather. Walter was in the lineup in right field as he had been in the previous few games and Tris Speaker back from his injury was in centerfield. Bing Miller made an appearance in the game as a pinch hitter. Walter went hitless in the game but did drive in one run in the 9–7 loss to the Yankees. Another name that appeared in the A’s lineup for the first time was Al Simmons, who pinch hit for Walter in the seventh inning, and got one hit, a single, and just like that Walter’s narrow window of opportunity in the 1928 season closed. In the remaining games with the Yankees, he only appeared once as a late inning defensive replacement for Speaker. New York swept the series and took a commanding seven game lead in the American League with a record of 30–7.

Finally on May 28th, in the A’s thirty-seventh game of the year, Connie Mack got to start his dream outfield starting Cobb in rightfield, Speaker in centerfield and Simmons in left but the Yankees still won 11–4. However, from that point on, when the dream outfield was not playing, Miller and Haas were Mack’s first choices to replace any of the regulars and Walter French remained the odd man out.

Over the next several weeks Walter continued to see limited action. From the end of May until the Fourth of July, nearly halfway through the season, Walter came to bat as a pinch hitter 10 times and came in as a late inning defensive replacement for Speaker or Cobb, coming to bat only twice in that capacity and in total he had three hits. While he was spending his time sitting on the bench the A’s were falling further behind the Yankees who at this point had a 12-game lead over the Athletics.

In July it appeared that Mack had given up on his “dream outfield.” The regular outfielders were now Ty Cobb in left field, Bing Miller in center field, and Al Simmons in right field. Any mention of Tris Speaker was in the role of a pinch hitter, who along with Mule Haas, appeared to be Mack’s go to men off the bench. Walter French made his first appearance on July 12, when he was used as a pinch hitter. He hit a single in a 4–3 loss to the White Sox.

On July 17 Ty Cobb had to leave the game against the St. Louis Browns after being hit by a pitch. Walter went into the game in right field and had one hit in two at-bats. The next day Walter got the start in place of Cobb, who was still recovering. He played right field and batted in the leadoff spot. He responded with two hits in five at-bats and he also scored a run as the A’s defeated the Browns in the second game of a doubleheader by a score of 4–3.

Cobb was back in the lineup on July 25, when the A’s defeated the White Sox by a score of 16–0. He came to bat three times and had two hits and scored three runs. He then came out of the game and was replaced by Walter French, who in turn went two for two with a run scored and one run batted in. At this point he had raised his batting average, albeit on a small number of chances, to .318. In the second game of the doubleheader, he went in for Cobb as a defensive replacement. The next day he did the same but did not get to bat. On July 27, he was sent in to pinch hit for the A’s shortstop Joe Boley. He remained in the game playing left field and came to bat three times. He had two hits, a single and a double, scored one run and had one run batted in as the A’s defeated the White Sox 7–4, raising his batting average to .333.

Over the next few games Mack’s outfield began to consist of Simmons, Haas, and Miller and however he was shuffling his lineup, it was working. The A’s had gone 25–8 in the month of July and had cut 6.5 games from the Yankees’ lead.

In the month of August, Walter French appeared in 11 games, 10 as a pinch hitter, in which he had one hit in with one run scored and one run batted in. He also came in as a defensive replacement for Al Simmons. In that game he came to bat once, hitting a double which drove in a run. The A’s had gone 19–9 for the month and had shaved another 4.5 games off of the Yankee lead. Going into the last month of the season only two games separated the first place New Yorkers from the second place Athletics. St. Louis in third place was 17 games behind the A’s. The Athletics followed with a record of 15–10 in September and finished the season in second place only 2.5 games behind the Yankees who had won 101 games to Philadelphia’s 98 wins. The Yankees went on to win their second consecutive World Series sweeping the St. Louis Cardinals in four games.

In the month of September, Walter appeared in only seven games, five as a pinch hitter. He finished the season with a .260 batting average. He had appeared in only 48 games and only had 76 plate appearances. It was the most time he spent on the A’s bench since his first season with the team. In a letter to a friend written some 50 years later he acknowledged that “1928 was a very disappointing year for me, as I had to compete with Cobb and Speaker. Both were over the hill. Sitting on the bench just wasn’t my cup of tea.”

As Walter reflected on the 1928 season and his role on the Athletics, he had to feel frustrated. What more could he do? When he played on a regular basis his numbers were as good as anyone on the team. What’s more, when he was in the lineup the team’s record, as seen in 1927, was a winning one. Contributing to his frustration had to be the knowledge that the game of baseball had changed and the skill set valued in a player earlier in the 1920s was not the same as what teams wanted and needed as the decade came to an end. Some 50 years later in an interview with sportswriter Greg Lathrop that feeling of frustration with the turn of events in 1928 was still present for Walter. Replying to a question about the acquisition of Bing Miller, Mule Haas, and Tris Speaker in 1928 he said “That left me sitting on the bench. That was one of my biggest gripes. I had a big year in ’27 and they still took on those other players.”27

Since the 1926 season Walter had been earning $7,500 per year, an amount which was supplemented by bonuses when the team finished high in the standings. And so, frustrated by his lack of playing time and feeling the pressure of now having a wife and two daughters to support, he announced that he was retiring from baseball on November 1, 1928. The Chester County Times reported with Chicago as a byline, “Walter French, for six years an outfielder with the Philadelphia Athletics, may have played his last major league baseball game. French has entered business in Chicago and has asked Connie Mack to put him on the voluntary retired list.”28 The Chicago business in question was Sears and Roebuck and his role was an unspecified “desk job.” Two days after Walter announced his retirement, Connie Mack announced that he had asked waivers on Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker and both men retired.

His stint working for Sears would be the only job that Walter French ever held to that point in his life that was not in professional sports or the military and it did not last long. Within a few weeks of accepting the position, he realized that he had made a big mistake and that a desk job too was “not his cup of tea.” As he thought about it, he realized that, as much as he hated it, sitting on the A’s bench was preferable to sitting at a desk all day. It may have been nothing more than that, but according to Walter he also had a dream that the A’s were going to win the pennant and beat the Chicago Cubs in the World Series and that there would be some World Series winnings in his future. “I worked hard all day,” he told sportswriter Harold C. Burr, “and did a lot of sleeping at night. Ordinarily I was too tired to dream, but one night something funny happened, something significant. I dreamed a tall thin man was holding something out toward me. I looked closer and saw it was a $5,000 bill. When I woke up, I didn’t have the five grand, but I had an idea … the tall thin guy was Connie Mack. It was a World Series check he was holding for me to take … Walter French couldn’t ignore such a series of suggestions. He threw up his job with a yell, wired Connie Mack, got Judge Landis to reinstate him, and bought a ticket to the Fort Meyers training camp of the Athletics.”29

How much the dream really had to do with his decision is unknown but on March 28 the Associated Press reported that “Walter French, Philadelphia Athletics outfielder, who retired from baseball last fall has been reinstated by Commissioner K.M. Landis and will report to the club in Philadelphia April 6, manager Connie Mack announced today. The former Rutgers and Army football star had terminated his professional baseball career to enter business.”30 Connie Mack agreed to keep Walter’s salary at $7,500 for the 1929 season.

In its preview of the upcoming season the New York Times rated the Yankees and the A’s as the teams to beat in the American League. Today it is hard to find a list of baseball’s greatest teams that does not include the 1929 Athletics, but in the days before the start of the season many of the prognosticators were giving the edge to the Yankees because of the results of the head-to-head meetings between the two teams in the last two seasons. In 1927, the Athletics were 8–14 against the Yankees while they were 83–63 against the rest of the American League. It was even worse in 1928 when they only finished 2.5 games out of first place, Philadelphia was 92–39 against the rest of the American League, while only 6–16 against the Yankees. The New York Times correctly stated that the A’s needed to get over the “apparent wholesome respect it has shown in the past for the Yanks when the two meet in hand-to-hand conflict.”31

Unlike the previous two seasons, the Athletics got off to a fast start in 1929. By the end of May they were sitting in first place with a record of 29–9, five games in front of the second place St. Louis Browns, and eight games in front of the third place Yankees. With the exception of the pitchers and Max Bishop, all of the A’s starters were hitting above .300, led by Jimmie Foxx at .434, Mickey Cochrane at .384, and Al Simmons at .346.

By May 31, Walter French had yet to start a game. He had two appearances as a pinch runner and four as a pinch hitter. On May 23 the Athletics were playing the Washington Senators and found themselves down 8–0 in the second inning. After George Earnshaw and Ossie Orwell failed to record an out in the first inning, Connie Mack brought in Bill Shores to pitch. In the fourth inning with the Athletics trailing 8–4 they loaded the bases and with Shores scheduled to bat Mack sent up Walter as a pinch hitter. He hit a double which scored three runs, and later came around himself with the tying run. The A’s scored another run in their half of the fifth inning and came away with a 9–8 win.

On May 26, Walter got some good news from New Brunswick with the announcement that he had been named, along with 15 other athletes, to the Rutgers Athletic Hall of Fame. His induction class included his former teammates Paul Robeson and Don Storck. Some 90 years later, in 2019, he would enter the school’s Hall of Fame a second time, posthumously, as a member of the 1919 basketball team.

The Athletics continued to dominate their opponents in the American League, including the Yankees. In the month of June, Walter French continued to be used sparingly. He went into a game against St. Louis on June 7 as a defensive replacement and got two hits in three times up and scored one run. He next appeared on June 16 as a pinch hitter and knocked in a run with a sacrifice fly against Cleveland. He pinch hit in the first game of a double header against the Yankees on Friday, June 21, but did not reach base, in a game the A’s won 11–1. The Yankees bounced back in the second game, winning 8–3.

Unlike today, where a doubleheader means that the same two teams will play each other on the same day, with usually one game being played in the afternoon and one at night, before two different crowds, for two admissions, doubleheaders, until recently, were two games played on the same day, in front of the same crowd and for one admission. On the weekend beginning on Friday, June 21, in addition to that day’s doubleheader, the two teams played two games on Saturday and one on Sunday. Over 186,000 fans packed Yankee Stadium to watch the series. The A’s won three of the five games.

By the halfway point of the season, the Athletics, with a record of 53–18, had built up an 8.5 game lead over the defending American League Champions. However, it was more of the same for Walter French in the second half of the 1929 season. He had a total of 10 at-bats in the entire month of July. His highlights were few and far between. On July 16, he was sent in as a pinch hitter in the top of the tenth inning in a game in Cleveland that was tied 5–5. Walter smashed a single to center field, which scored Dykes with what would turn out to be the winning run.

By August 1, the Athletics had built their lead over the Yankees to 10.5 games. Walter only came to bat five times in the first three weeks of the month of August. Finally, on August 21, Connie Mack announced that he was giving Al Simmons a few days off to visit his family and rest his legs, and so on that afternoon Walter French made his first start of the season against the St. Louis Browns playing left field. In the top half of the fifth inning Walter hit a long fly ball toward the gap between left and center fields. Thinking he had just made a long out he tossed his bat in disgust and started running toward first base. He then realized that the two Browns’ outfielders, Fred Schulte, and Heine Manush, were both yelling “I’ve got it.” When neither man yielded, they collided and the ball rolled toward the wall. The newspapers reported that French “tore around the bases” for an inside the park home run.

Two days later he filled in for Simmons again in Chicago. The Athletics lost to the White Sox but Walter had a successful sacrifice in the first inning, moving Max Bishop from first to second. He later drew a walk and singled to center. However, Al Simmons’ break was indeed to be a short one as he was back in the lineup on August 24. The rest apparently did him some good as he went three for four and knocked in two runs.

At this point in the season the Athletics were running away with the American League Pennant. They held a commanding 13.5 game lead over the second place Yankees. Offensively the team was led by Jimmie Foxx who was hitting .376, while Al Simmons was hitting .365, Mickey Cochrane .326, Bing Miller .337, and Mule Haas .305. After a tough series with the Senators, the A’s squared off against the Yankees in a three-game series during the first week of September. If the Yankees were to have any hope of making the pennant race interesting, they would have to sweep the series. However, unlike in the previous two seasons where the Yankees dominated the Athletics in their head-to-head meetings, Philadelphia crushed any hope the Yankees might have had coming into the three-game set. The A’s swept the series and outscored the Yankees 26–10 and in the process, extended their lead to 14.5 games with the regular season in its final weeks. By September 12, the race was over as the Athletics had clinched the pennant. At this point Connie Mack had started to rest some of his starting players. On September 20, Mack inserted Eric McNair, a late season call up from the A’s minor league team in Knoxville, TN, at shortstop in a game against the Tigers. McNair responded by getting three hits. With the game tied in the bottom of the tenth inning, Bevo LeBourveau was walked. McNair then hit a ground ball to short forcing LeBourveau out at second. McNair then stole second base. Walter French was then put in to pinch hit for Al Simmons, and he singled home the winning run.

Walter’s last appearance in the 1929 regular season was on October 6, in a game against the Yankees. He first entered the game as a pinch hitter for pitcher Rube Walberg, and then stayed in the game relieving Bing Miller in right field. He finished the year with one hit in two at-bats and scored one run.

As the season came to an end the Athletics had won the pennant by 18 games over the defending American League champions. The concern the experts had at the beginning of the season about the “wholesome respect” the Athletics had shown to the Yankees in their head-to-head matchups in past years, turned out to be unfounded in this campaign, as the A’s finished with a record of 14–8 in games with New York. They had taken over first place in May and had never relinquished it. Their pitching staff boasted of three of the league’s best pitchers, Lefty Grove who finished the season with a record of 20 wins against only six losses, George Earnshaw who finished at 24–8, and Rube Walberg who turned in a record of 18–11.

Matched up against the Philadelphia club in the 1929 World Series were the Chicago Cubs. Although the Cubs were not as dominant in the regular season as were the Athletics, they walked away with the National League pennant in an impressive way. They finished with a record of 98–54, some 10.5 games ahead of the second place Pittsburgh Pirates. The Cubs were led by future Hall of Famers Rogers Hornsby and Hack Wilson. Hornsby, playing in his first season with the Cubs, had 229 hits in the regular season and knocked in 149 runs. Wilson had 198 hits, including 39 home runs and he knocked in 159 runs. The ace of the Cubs pitching staff was Pat Malone. Malone was a right-handed pitcher from Altoona, PA, in his second season in the major leagues. He finished the 1929 season with a record of 22–10.

In the lead up to the World Series the oddsmakers had installed the Athletics as slight, 11–10 favorites to win the title. It was also announced by Commissioner Landis that NBC had been selected to broadcast the Series. Graham McNamee, who is often credited with originating play-by-play sports broadcasting, was selected to call the games for the network.

The Athletics checked into the Edgewater Beach Hotel located near Wrigley Field on the north side of Chicago prior to the start of the series. When Connie Mack spoke to reporters from his suite at the hotel he was willing to discuss any topic but refused to reveal the name of his starting pitcher for game one. Joe McCarthy, manager of the Cubs had announced that Charlie Root would start the game for his team. Root was a 30-year-old right-handed pitcher, in his fourth season of a 16-year career with the Cubs. Root finished the regular season with a record of 19–6.

Even though Connie Mack would not discuss who he was going to name as his starting pitcher the newspapers were convinced that his silence was just some gamesmanship on his part and his choice would ultimately be one of the two aces on his staff either George Earnshaw or Lefty Grove. The Boston Globe ran a story on the front page of its sports section stating that Earnshaw would likely be Mack’s choice to face Root, while UPI proclaimed that either Earnshaw or veteran Jack Quinn would get the start. Speculation was that because the Cubs had a lot of success against lefthanders during the season, Mack was leaning toward starting a righthander like Earnshaw or Quinn. “You’ll know my pitcher fifteen minutes before the game,” Mack told the reporters. The A’s pitchers most mentioned as starting possibilities were Grove (if Mack opted to go with a lefthander) Earnshaw, and Quinn.

The Philadelphia Athletics arrive in Chicago for the start of the 1929 World Series. Walter French is in the front, on the right, holding a suitcase. (Courtesy of French Family)

However, despite giving the impression that he was still making up his mind on who would start the game for the Athletics and would not decide until just before the start of the Series, Connie Mack had known for two weeks who would get the call and it was none of the names being bandied about. He had made the decision to start Howard Ehmke, the 35-year-old right hander, who had only appeared in 11 games all season. In fact, only three people in the world knew of Connie’s plan, Mack, Eddie Collins, and Ehmke himself. Years later Connie Mack recalled that Ehmke told him that his one regret in his baseball career was that he had never won a game in the World Series. “Howard,” Mack said, “You’re going to pitch that game in the series. You stay home and work out here in Philadelphia. When the Cubs come here in their final games with the Phillies, go to every game and study their hitters carefully.” Mack told him that he was to tell no one. Mack figured that “a major surprise at the outset would break their spirit, so my strategy was to nullify the Chicago plan of campaign at the start.”32 He felt too, that if Ehmke could pull off the improbable and win Game 1, that it would cause the Cubs to doubt their chances against the A’s big three Earnshaw, Grove, and Walberg. It was also true that the Cubs were a great fastball hitting team, and when on his game, Ehmke was an off-speed pitcher with a big breaking slow curveball and was likely to give the Cubs trouble.

On game day Mack had still not named his starting pitcher as the players took the field for their warmups. “At one point Ehmke sat down on the bench next to Mack. ‘Is it still me Mr. Mack?’ he asked. ‘It’s still you,’ Mack said. Fifteen minutes before game time, Ehmke took off his jacket and started to warm up. Jaws dropped in both dugouts and among the 51,000 fans in attendance. Grove and Earnshaw stared at each other in disbelief. Ehmke hadn’t pitched in weeks.” Sitting near Mack, Al Simmons reportedly asked his manager “Are you going to pitch him?” to which Mack replied, “do you have any objections to that?” “No,” Simmons replied, “if you say so it is alright with me.”33

Over the next two hours Howard Ehmke put on a clinic on how to pitch to the hard-hitting Cubs team. Years later, Cubs Shortstop, Woody English told Sports Illustrated that he recalled that Ehmke “looked like he didn’t give a damn what happened. He threw that big, slow curveball that came in a broke away from the righthanded hitters.”34 Given that all but one of the Cubs players was right-handed, Ehmke’s style was perfect. “Ehmke was a change from the guys we were used to, who threw hard,” English told Sports Illustrated, “not that many pitchers used that stuff against us.”35

In fact, both pitchers were performing well and the game was scoreless when the Cubs came to bat in the bottom of the sixth inning. The Chicago fans were excited as their number two, three and four hitters were scheduled to bat. Woody English who had hit .276 during the regular season was leading off the inning followed by Rogers Hornsby who had hit .380 and Hack Wilson who had hit .345. Unfazed, Ehmke proceeded to strike out all three of them.

In the top of the seventh inning, Root retired Al Simmons on a fly ball to centerfield. This brought up first baseman Jimmie Foxx. Foxx, in his fifth major league season, had improved on his breakout year of 1928 and in 1929 had emerged as a star in the league and a prolific power hitter, recording 33 home runs and 118 runs batted in. Foxx crushed a Charlie Root pitch over the fence in centerfield, some 400 feet from home plate, to give the Athletics a 1–0 lead.

In the bottom of the seventh inning the Cubs mounted a threat. Kiki Cuyler led off with a single followed by a single from Riggs Stephenson which put men on first and second base. Charlie Grimm then laid down a perfect sacrifice bunt which moved Cuyler to third and Grimm to second with only one out. This brought up Cliff Heathcote with the go-ahead run-in scoring position. Ehmke got Heathcote to hit a harmless fly ball into short left field for the second out without either runner advancing.

At this point Cubs manager Joe McCarthy inserted future Hall of Famer Gabby Hartnett into the lineup to pinch hit for Charlie Root. Hartnett had been used on a very limited basis during the 1929 season as he tried to recover from an arm injury. Ehmke struck out Hartnett, his twelfth strikeout of the game, to end the inning and the Cubs threat.

Joe Boley led off the top of the eighth inning for the Athletics by grounding out to shortstop. This brought up Howard Ehmke, and even though Philadelphia was clinging to only a one-run lead, Mack had no plans to fix what wasn’t broken and sent Howard up to bat for himself. He immediately hit a single to right field. However, Max Bishop and Mule Haas each flied out to end the inning and stranded Ehmke on first.

Howard made short order of the Cubs in the bottom of the eighth inning, when he got Norm McMillan and Woody English to fly out to centerfield and rightfield respectively. This brought up Rogers Hornsby again but Ehmke retired him on a ground ball to second baseman Max Bishop.

In the top of the ninth inning Mickey Cochrane led off the inning with a single to center field. Then on two consecutive plays Cubs shortstop Woody English committed two errors on balls hit to him by Al Simmons and Jimmie Foxx, which loaded the bases. Then Bing Miller lined a single to centerfield scoring Cochrane and Simmons and moving Foxx to third base. Jimmy Dykes and Joe Boley then reached base on a fielder’s choice when Foxx and Miller were both thrown out at home plate.

After Howard Ehmke made the final out for the Athletics in the top of the ninth, he came out to pitch the bottom half of the inning. Hack Wilson led off for the Cubs and bounced back to the mound where Ehmke threw him out at first. Kiki Cuyler then hit a ground ball to third where Jimmy Dykes fielded it cleanly but made a wild throw to first, allowing Cuyler to get to second base. Riggs Stephenson then hit a single scoring Cuyler. Stephenson advanced to second when Charlie Grimm hit a single. Pinch hitter Footsie Blair hit a grounder to Dykes who threw to second for out number two. McCarthy then sent Chick Tolson up to pinch hit for pitcher Guy Bush who had gone into the game when Root was lifted for a pinch hitter. With Stephenson on second and two out, Tolson represented the tying run. Seemingly impervious to the pressure of the situation, Howard Ehmke struck him out to end the game. It was Howard’s thirteenth strikeout which, to that point in time, was a World Series record, breaking the previous record of 12 set by Ed Walsh of the White Sox in the 1906 World Series. It still ranks in the top four of all time. Only Bob Gibson, Sandy Koufax, and Carl Erskine have struck out more than 13 batters in a World Series game.

In the wake of the performance by Howard Ehmke the sportswriters were focused on Mack’s decision to start him. Was it a further sign of Connie’s genius or was it just a lucky hunch on his part? Frank Getty, Sports Editor at United Press International concluded that “knowing Mr. McGillicuddy for one of the smartest men in the national pastime, one is inclined to credit him with just some touch of super-strategy.”36 Looking back on it years later Mack would write “It was one of the greatest thrills in my life to see Ehmke pitch that game and break a world’s record. He smashed the record that Big Ed Walsh had held for twenty-three years.”37

For Game 2, Mack selected George Earnshaw to start for the Athletics against Pat Malone. This game would lack the drama of Game 1 as Jimmie Foxx got the scoring going in the third inning when he hit his second home run of the series, a three-run shot to deep left field. The A’s scored three more runs in the fourth inning to take a 6–0 lead. However, in the bottom of the fifth inning the Cubs offense finally came to life. After Woody English flied out to third, Rogers Hornsby singled to centerfield and Hack Wilson did the same. Earnshaw then struck out Cuyler and for a moment it looked like he would get out of the jam without any damage but then Stephenson, Grimm, and Zach Taylor wrapped out consecutive singles and three runs came across for the Cubs. Having seen enough, Mack replaced Earnshaw with Lefty Grove who struck out Gabby Hartnett to end the inning. At this point the Cubs manager Joe McCarthy took Malone out of the game and sent in Hal Carlson.

Both teams failed to score in the sixth inning but in the top of the seventh Jimmie Foxx hit a leadoff single. He was then moved to second on a sacrifice bunt by Bing Miller and scored on a Jimmy Dykes single. Now staked to a 7–3 lead, Grove retired the side easily in the Cubs half of the inning. In the top of the eighth inning Carlson retired Max Bishop and Mule Haas before walking Mickey Cochrane. The next batter, Al Simmons then blasted a home run deep into the seats in right field to give the A’s a 9–3 lead. Lefty Grove did his job and recorded the last six outs, game two was in the books and the Athletics were heading back to Philadelphia with a 2–0 lead in the series.

However, any thought that the Cubs would go quietly was disproved in Game 3. The A’s bats went quiet as Guy Bush, who won 18 games in 1929, held them to one run. George Earnshaw, having only pitched into the fifth inning in Game 2, got the ball to start the game for the Athletics. He gave up three runs in the sixth inning on hits by Hornsby and Cuyler.

Frank Getty noted that Philadelphia lacked “Pep.” He went on to observe that the “Mackmen did not show to advantage in their first appearance before their own fans yesterday. Jimmie Foxx, the versatile first baseman, who was the hitting hero of the game in Chicago, couldn’t bat a ball out of the infield. Al Simmons went hitless. Jimmy Dykes, the most popular of the whole lot with the Shibe Park fans, had the misfortune to contribute the misplay which helped along the three-run Chicago rally in the sixth inning.”38 The Athletics left 10 men on base in the game.

The next day, Jack Quinn, who many had speculated would get the start in Game 1, was selected by Connie Mack to pitch in Game 4. Again, it appeared that Mack was trying to keep the Cubs right-handed hitters off balance. Quinn had finished the regular season with a record of 11–9, so there were more accomplished options available to the manager. Charlie Root, the Cubs game one pitcher was back on the mound for the visiting team.

The confidence level of the Cubs and their fans was sky high as game time approached. The Chicago Tribune had published a list it called “Ten Reasons for Elation for the Cubs.” One of the reasons listed was “Malone and Blake, as well as Root, believe that they have discovered how to pitch to Simmons and Foxx both of whom batted .000 against Bush”39 in game three.