3

UNTOLD THOUSANDS OF SUDANESE BOYS WALKED HUNDREDS OF miles through the wilderness to seek refuge in Ethiopia in 1987 and 1988. Relief workers reported seeing 17,000 “walking skeletons” arrive at the Ethiopian camps. An American diplomat cabled the State Department that all of the refugees “had the dull concentration camp stare of the starving.” Their evident suffering resembled World War II photographs of the victims of Nazi concentration camps, the diplomat wrote, and “were as bad or worse” than anything seen in Ethiopia during the 1984-86 famine. Interviewers concluded that hunger, thirst, disease, animal attacks, and human violence claimed many lives before the refugees could reach the Ethiopian border.

They came in search of food, education, and freedom from suffering. Some came to find the SPLA training camps, so they could learn to fight the djellabas. The SPLA called the boys they recruited “child soldiers” and ran a training camp in Ethiopia. They took some of the oldest, strongest boys and left the rest to get an education. This generation would need to be educated to help Sudan once the war was won.

Four southwestern Ethiopian relief camps supported 265,000 Sudanese refugees in mid-1988. Most were boys and young men. Relief workers who surveyed camp residents found variations on the same story: They had fled Muslim troops and government-backed enemy tribesmen who attacked their villages, killing men and boys and taking women and girls as slaves. Mothers and daughters were not as ready to move quickly when the attacks came, a Sudanese leader of the refugees said. They fell behind and were more likely to be caught. Only a few hundred girls and a handful of women made it to Ethiopia. In all, about two million of the six million Sudanese living in the southern provinces had fled their homes because of famine or civil war by mid-1988; many settled in other parts of Sudan.

Thousands of Lost Boys trudge along a path in southern Sudan after leaving Ethiopia.

Newcomers “are nothing but skin and bones when they arrive,” an aid worker who visited the refugee camps in Ethiopia, including Pinyudu, told the New York Times. “They tell us that 20 percent of the people who left with them died along the way.” Other estimates placed the number of deaths in transit from all causes—hunger, thirst, disease, and violence—as high as three in five. One boy told an interviewer he followed a trail of human bones to find his way to Ethiopia. Sadly, his odyssey and those of the other Lost Boys and Girls did not end in Ethiopia.

“CALM DOWN, CALM DOWN,” OUR CAMP CARETAKERS KEPT shouting at us as we stood on the banks of the rain-swollen Gilo River. But we could not stay calm. We were trapped between the crocodile-infested river shallows and hundreds of Ethiopian soldiers, who were trying to kill us or drive us into the water.

Only a few moments before, I had been eating some boiled maize on the riverbank. It had been a calm and overcast afternoon in May 1991. I had unslung my pack and placed it on the ground to make an easy chair for my back while I ate lunch. Around me, hundreds of other boys relaxed and moved lazily, not doing much of anything, and certainly not doing it in a hurry.

Then I heard the fttt of rocket-propelled grenades being launched and the whump of nearby explosions. Boys burst into a dead run like carrion crows startled by a stone. Some passed me and headed toward the river, surging below a ten-foot embankment.

I leaped up, scattering cornmeal, and looked for the source of the sounds. On the horizon, a line of Ethiopian soldiers advanced toward us. They wore dusty military uniforms of tan and pale green. Some strode forward in their black boots, firing rifles and RPGs; others must have stayed in the rear because I heard the whine of incoming mortar shells zooming over the soldiers’ heads in long parabolas. A few armored vehicles rumbled across the plains, firing shells plumed by telltale puffs of black smoke. Bullets zipped through the air. They were close enough for me to hear their birdlike kee kee as they passed.

“We are attacked!” someone yelled. Others took up the same shout. Many boys started to cry. Some had the frozen look of panic in their eyes.

I snatched at my traveling pack, which I had sewn in Pinyudu refugee camp from plastic sheets and rectangles of cloth sliced from bags that said “USA.” One handle snapped as I tried to lift it to my shoulder. I threw the useless bag down and ran toward the river.

Not being a good swimmer, I frantically looked for a place where the edge dipped gently to meet the river. While I searched, tall, coal black Sudanese boys made leaps of faith around me, jumping at full speed without looking to see where they would land. I froze. Why was I looking for an easy way to enter the water, when soldiers were trying to shoot me from a few hundred yards away?

Here’s faith, I thought. I leaped, too.

I hit the mud at the reedy edge of the river. The impact smashed the air out of my lungs, but I had no time to recover. I struggled into the muddy water and began to kick toward the far side. A big man, from the Nuba tribe by the looks of him, appeared in the water beside me. He could not swim and grasped at anything to keep from drowning. Seeing me, he wrapped his arms around my head in his panic and pushed down. I fought to force him off, but he was too heavy and strong. We slipped beneath the surface. I tried to scream and got only a mouthful of water. In the silence of the river’s depths, I became aware of many other legs and arms churning the water around me into foam.

The Nubian kicked his legs and got his head above the water for a moment. In pushing up, he relaxed his hold on my head. I broke free and popped up beside him, taking an enormous gulp of air. The Nubian grabbed my head again.

“Sadi ana! Sadi ana!” he yelled. It was one of the handful of Arabic phrases I had learned in Pinyudu. The Nubian whose panic had nearly drowned me was pleading, “Help me, help me!”

“I can’t help you,” I panted in Arabic, just before I went under the water again. At home in Duk Payuel, I learned how to swim on my back, much better than on my front. When I surfaced, I flipped face up and started to backstroke. I stared up at the sky and paddle wheeled across the water.

Time slows when your life is in danger. Every second takes a minute to pass, and even the smallest event gets chiseled into memory. It took a moment for me to realize the Nubian had let go. Good for me, bad for him. I began moving toward the opposite bank with a steady stroke. I turned my head left and right to look for the Nubian, but I could not see him in the chaos of waves and flailing limbs. All over the surface of the river, similar dramas of survival were being played out as swimmers struggled toward the far shore and nonswimmers grasped for anybody or anything that floated. Shrapnel tore into bodies and sent pieces of arms and legs flying through the air. Some people sank to the bottom and did not resurface. Others grabbed onto floating corpses and body parts.

Bullets pinged into the water and screeched overhead. They made a dull splat when they hit flesh or the mud of the western bank. Open wounds turned the water red. Crocodiles will smell our blood, I thought, but fortunately I did not see any in the water near me.

Another boy grabbed my torso; I was not sure of his tribe. “If you hold me like that I can’t push water! I can’t carry you!” I screamed. He relaxed his grip. I wrapped one hand around his upper arm and began paddling with my free arm. After a few strokes, I switched hands and kept going. We made slow, steady progress that way, with me changing my grip from hand to hand as I kicked and reached for the far, tree-lined shore. It was only a few hundred yards, but it seemed an eternity.

At last I felt the mud beneath me. We had made it across. The ten-minute crossing of the channel seemed as if it had taken an hour. My companion gave me a final push to plant his feet and scrambled up the bank. I followed, crawling on all fours. As I reached the top of the bank, I turned and looked at the eastern shore. Smoke and dust rose in clouds from the far bank. I heard the crump of mortar tubes somewhere to the east and the rattle of automatic rifles.

Shells exploded on the ground in front of me. I would have to run through the bursts to escape, I thought. But at least the river would stop the advance. Only a madman would pursue his enemy through swift, crocodile-filled waters. I thanked God that armored vehicles could not float.

I turned and hustled in a deep crouch, half-running and half-crawling across the grass and into a field showered by dirt clods kicked up by bursting shells. Bullets fired from the far shore sped by me, cutting down boys who rose up too high. I looked for my companion on the swim across, but he had disappeared. I never saw him or the Nubian again. I kept going until the shells stopped exploding around me. Then I walked until I was sure I was safe.

Hours later, after the survivors reassembled, we shared stories of the crossing. A few of the lucky ones had held onto a rope the caretakers had managed to string across the river and hand-walked to safety. Others found small boats along the riverbank and tried to make the crossing in them, but at least one of them overturned in midstream. Four young men who had sat in the boat went into the water; a crocodile took one, and the other three drowned. One boy who made it to the other side incongruously had a live goat thrust into his open arms by another survivor. Blood burst as the boy held the goat. He checked to see if he had been hit. No, the bullet had hit the goat, killing it instead of him.

Perhaps 20,000 Sudanese boys went into the Gilo River that day. Nobody knows how many died in the crossing. Maybe 2,000, maybe 3,000, maybe more. Some drowned. Some caught a bullet or shell fragment. Some found their way into a crocodile’s belly. I know the crocs had a feast, because others who made it to the western shore told me they had seen their friends in the beasts’ cold jaws. One man showed me the stump of his hand and told me a crocodile bit it off while he swam. Later, in Kenya, the boys started calling him Mkono Umja—“One Hand Man” in Kiswahili.

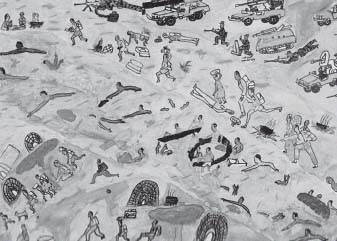

Refugees flee across the Gilo River ahead of Ethiopian troops in a painting done by a 17-year-old Lost Boy at Kakuma.

A week before the attack at the Gilo, nobody could have foreseen such chaos and death. We had grown accustomed to life in Pinyudu and had expected to live there a long time. We had our homes, our meals, our games, and even some of the sweeter things in life, such as our traditional songs and dances. I certainly did not think the war we had left in Sudan would find us.

But if I had listened more closely to our caretakers, I might have suspected something was up. In April 1991, they told us of troubles facing the Ethiopian government, which had sheltered us and allowed the UN to bring us food. Ethiopia had its own civil war—rebels, friendly with the northern Sudanese, were fighting against the socialist government of President Mengistu Haile Mariam. The caretakers said that if the rebels took power, they would not let us stay. “If they come,” the caretakers said, “we will have to run away to a different place.” That did not sound too bad. I could go to another camp if I had to.

The boys in my group discussed the likelihood of our leaving Pinyudu. That spring, the rains came to dusty western Ethiopia as never before. We stood in a circle under a tree near our hut and talked as the rains pelted the camp.

The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front captured Addis Ababa on May 21 and sent Mengistu packing. He fled to Zimbabwe, leaving the government in the hands of our enemies. In Pinyudu, at the edge of Ethiopia, we heard the news almost immediately. The new government gave us a week to leave. That left us with no opportunity to harvest the corn and vegetables we had planted near our huts.

“Now,” the camp manager announced at an assembly, “we have no choice. There is another war, and there is no place for us here.”

I wondered where we would go. Back to our villages, I hoped. I wanted to look for my family. But then I considered more carefully. Nothing had changed in Upper Nile Province. The northern djellabas still controlled most of the villages, and there would be no life for me anywhere near such people, as long as my country was at war with itself.

“Pochala would be a good place,” someone said. It was not far from the Ethiopian border and still in the hands of the SPLA. I was not too excited about returning to a Sudanese town certain to draw the attention of the djellabas, but I could see no good alternative. We had to choose the lion in Ethiopia or the hyena in Sudan.

Pochala, I thought. I would have to go there, even though it meant returning to the hand-to-mouth life I had lived with Abraham on the walk to Ethiopia. As I thought about my future, I discovered a nagging voice in the back of my mind that said something bad would happen soon. It was the same feeling I had felt in Duk Payuel in the days before the djellabas came.

OUR EVACUATION FROM PINYUDU HAD BEGUN AS AN ORDERLY affair. The caretakers announced that the best way to stay organized was to have one group leave each day, starting immediately. The first group of 1,200 set out that very day, walking and carrying food and supplies toward the western border. A second group took off shortly after noon the next day. At that rate, clearing camp would take a couple of weeks.

I was in the third group. Every boy had a bag like the one sewn from American cloth sacks and bits of plastic tarpaulin. I told my housemates to put their tools and extra clothes in the bottom of their bags and put a little food on top. I made sure everyone carried a bit of corn or vegetable oil.

“There may be no food later,” I said. “Carry what you can.” Around 3 p.m. on the third day of evacuation, my group started moving toward the Gilo River at the western edge of Ethiopia. We followed in the footsteps of the first two groups. The brown land, dotted with hardy grasses and pools of mud, passed monotonously underfoot. Bushes, flowers, and trees encouraged by the rains had sent forth armies of fresh shoots, covering the plains with a pale green blanket. Mosquitoes buzzed around me as I walked. Every evening we made camp under the sky, opened our bags, and cooked corn meal mush for dinner. Our cooking fires sent drifts of white smoke into the night sky, and blossoms of orange flames dotted the dark landscape with a comforting glow. If not for my nagging suspicions, I might have been able to relax and treat the journey like an adventure. I tried to sleep, but the weather was cool, and the clouds that gathered tickled me with drops from a steady drizzle.

It took four days before my group reached the Gilo. The first two groups already had arrived. Many of the boys could not swim, so the caretakers debated the best way to get to the other side. Someone suggested trying to hire the native Anyuak to ferry us across in their little boats. The caretakers investigated and found that idea had two problems. First, it was a seller’s market. The Anyuak had a monopoly on boats, and they set their price too high to accommodate everyone. Second, the boats were so few and the numbers so large—and swelling by 1,200 or so every day—that it would have taken many days to get everyone across.

The caretakers settled on a plan to string a rope from shore to shore a few feet above the water and secure it to trees at each end. They scouted the best location for anchors on both banks of the river. Meanwhile, more and more boys packed the eastern side of the Gilo.

Each night brought cool temperatures. Each morning dawned warm and pleasant. Each day, I wondered, would this be the day I would cross? Would I be safe?

I did not know that as the refugees from Pinyudu assembled on the grassy bank of the Gilo, military units dispatched by the new Ethiopian government were approaching the river from another direction. The shooting started on my fifth day. I was just beginning to relax and eat as the sun struggled to fight through a scattering of clouds. I did not hear or see any warning. Only after I had crossed to the western side did I learn that boys in another group had met an SPLA soldier on the east bank before the attack started. He reported fighting between Sudanese militia and Ethiopian soldiers at Pinyudu, after the refugees had left. It was common knowledge that the SPLA had soldiers in and around our camp to recruit for the southern Sudanese militias, and that they trained on Ethiopian soil. The SPLA soldier had said he expected the Ethiopians to pursue all of the Sudanese to the Gilo, and he was right. If only that message had gotten to everyone sooner, perhaps more lives would have been saved. As it was, it seemed a miracle that only a few thousand of us died in crossing the river.

Like most survivors of that day, I still have bad dreams about the Gilo River. And I wonder still, what does war do to people to make them shoot children? Do those Ethiopian soldiers ever get nightmares?

AFTER MY ESCAPE ACROSS THE GILO, I STAGGERED FORWARD FOR many hours. Nobody in my group had any food; we had left it on the eastern shore as we dived into the river. About 18,000 boys from Pinyudu trudged toward Pochala. Boys from other refugee camps in Ethiopia joined us. The line stretched so long that two days passed between the first boy and last boy crossing the same spot in the muddy road.

The Anyuak of Sudan welcomed us. I found some fruit growing in the Anyuak forests, and they gave us some of their own food to eat. It barely took the edge off my hunger. My stomach growled and my legs ached, but I kept walking, willing my feet to pull free of the sticky mud and take one step closer to Pochala.

Lost Boys on their way toward the Kenyan border

sleep in the desert of southern Sudan.

We arrived to find Pochala a friendly but broken town. The SPLA had captured it from the djellabas, but the fight for control had reduced much of the town to ruin. Caretaker adults—perhaps 200 of them had survived the Gilo—showed us where we could find temporary shelter. I and a few hundred other boys spent our first nights in an abandoned military barracks.

Soldiers came to talk to us, telling us about the war in Sudan. Some of my friends met soldiers from their villages, but I never met anyone from Duk Payuel. The soldiers gave us a little of their food. It never lasted long. The SPLA could not support tens of thousands of children on their own.

We had no idea then that we would have to stay in Pochala for nine months with no guaranteed supply of food. The wet season rains pelted us and covered the ground with mud. Pochala became an island surrounded by swamp, impossible to cross in a car or truck. No food came over the submerged roads. I started feeling hungry all the time.

During my second month in Pochala, I heard the sound of an airplane overhead. For a split second, I hoped it might be a United Nations plane making a food drop. Then the sound resolved itself into the characteristic ooooovvv of Antonov engines. It was a warplane from the Khartoum government. The plane flew over the town and dropped a string of bombs. They kicked up fountains of dirt as they hit near the camps, and a few boys were injured. As soon as the plane left, I started digging, because I knew the Antonov would return. Everyone else must have had the same idea, for soon the streets of Pochala were crisscrossed with trenches.

I built a hut from branches and mud where I could store any food I found, and a trench not far from the door to the hut that I could dive into. It wasn’t many days before the Antonov returned, and my trench served its purpose. The plane came back a few days each week, and my body instinctively jerked toward the trench as soon as the faintest engine noise drifted over the trees.

Food became extremely scarce even as the swamps began to dry. The SPLA soldiers said they had no more food to give us, and we were on our own. Most wild fruits hadn’t ripened yet. I knew of a few that should have ripened and combed the forests for amochro, which Abraham had showed me how to find, as well as waak, a shrub that bears a white, sweet fruit with a funny after-taste. I also resigned myself to eating the fruit of the gumel. It’s a huge tree, with a sweet-and-sour fruit about the size of a baseball. Everyone knew eating the gumel fruit brought on the symptoms of malaria, but that was better than starving. I weighed my options and ate. The fruit made me sick, yet it kept me alive.

We also took clothes to the Anyuak and bartered them for food. In my circle of a few dozen boys, we asked one who had a T-shirt to give it up so we could get some corn. Another boy washed it and took it to the Anyuak outside the village, and we got enough corn to keep us alive for a few more days.

The exchanges always had risks. The Anyuak nearest Pochala quickly realized how desperate we were, and they offered less and less for our articles of clothing. Things got so bad that one local trader offered only a cup of corn for a shirt. We refused. The Anyuak sneered at us. “Go and eat your clothes,” they said.

We traveled farther from town, and indeed the price rose higher. But there was danger in wandering too far. I heard about some boys, not from my group, who wandered so far in search of a good price that they were captured by hostile Anyuak and killed.

I found myself using words like “killed” and “died” in conversations without giving them much thought. How much I had changed, I thought. In the Dinka tradition, children were shielded from death. In fact, the news of a loved one’s passing was kept from children as long as possible. An elderly neighbor was supposed to break such news, very carefully, first to the adults of a family after having prepared them with small talk and references to the mortality of men and women. Then the adults gently told the children. Everyone cried, even the men, and the women sometimes threw themselves on the ground in their wailing and mourning. In Duk Payuel, my relatives took off all of their jewelry, wore only black clothes, and let their hair go unattended after a death. It was all an elaborate process meant to demonstrate the esteem in which the dead person was held. In our refugee camps, however, the necessity of burying so many children telescoped the ceremonies of mourning into a few moments of silent grief. I helped bury the people I knew, I said a few words of prayer, and I moved on. I had no black clothes to wear, and my hair already was very dirty and likely to get much dirtier. I felt as if I had grown up too fast. Death had become all too familiar.

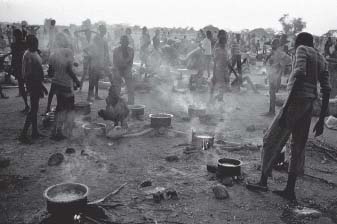

Sudanese children cook beans at a camp near the Kenyan border.

The UN supplied refugees with food during their journey.

I asked the caretakers why the UN, which had fed us in Pinyudu, couldn’t bring us food in Pochala. They replied that the town had no roads for overland supply and no airfield where planes could land. Not long afterward, the caretakers put us to work clearing space for a landing strip. I helped dig up roots and cut down trees with axes supplied by the SPLA. Slowly, the strip took shape on the outskirts of town.

The first time a giant cargo plane flew over the town, I ran away. I thought it was another bomber, and a big one at that. The plane dropped bags onto the open fields. Only after it had flown off did I and some of the other boys go to look at the bags and discover they were full of food and secondhand clothes. Soon we came to distinguish the deep throbbing of the relief planes’ engines from the droning of the Antonovs and ran to pick up the shipments as they streamed toward the ground. Some planes from the International Red Cross and the UN landed, and others dropped maize, oil, beans, and medical supplies from midair. One drop killed two boys when bundles of food and medicine fell on them. After that, all planes landed for deliveries for a while.

The food came just in time. Pochala’s refugee population had swollen to perhaps 80,000 with an influx of southerners made homeless in the new round of fighting. Many boys I knew had sold all of their clothes to the Anyuak and were naked again. When clothes arrived in the airplanes, I worked with some of the older boys in my group to distribute them wisely. I decided that if a boy was completely naked, he had first choice on an article of clothing. Boys who already had shirts or pants chose much later. Most boys picked through the clothes and selected an adult shirt. The shirt tail hung around their knees, covering them like a dress. Underneath they wore nothing. That seemed a good choice for naked boys who only got to pick one article of clothing—it kept them warm but could be hiked in a hurry when they felt an attack of diarrhea coming on.

I didn’t get any new clothes for a long time. I still wore the colorful blanket-shorts that Abraham had made me, and I was naked from the waist up for several months. The shorts had suffered many tears over the months I had worn them, but I had learned how to sew and kept them patched. The SPLA kept me supplied with needles. Finally, I got a long T-shirt and wore it with my shorts.

As the weather grew cooler and drier, the Antonov sorties grew more frequent. We wondered if the northern government deliberately targeted boys, as we were the vast majority of the town’s occupants. Bombing runs hit Pochala every day, in the morning and afternoon. I started to anticipate the explosions. I played soccer with my friends, using a ball made of socks, and we suspended the games around 3 p.m. to be near our trenches when the bombers passed over. Still, casualties started to rise, not only from direct hits during the air raids but also from the Anyuak. They didn’t like their forests being bombed, and they shot a few boys and SPLA soldiers in Pochala to scare the rest of us enough to move on. The Anyuak called us ajuil, the name of a small antelope that lives in the forest. It always seems to be on the move, wandering without a home. The Anyuak couldn’t understand why we wandered without settling, preferably elsewhere.

Raids also hit the town of Torit, where a bomb exploding in the market killed more than 30 people. And once, 200 soldiers who crossed into Sudan from Ethiopia attacked Pochala briefly before withdrawing. Some boys left Pochala with Red Cross workers, who promised to reunite them with their families, but most refugees stayed. They had no families to be found.

IT’S STRANGE TO SAY IT ABOUT SUCH A VIOLENT TIME, BUT I WAS happy. I had a daily routine of cooking, games, and building huts and trenches to keep my mind occupied. Corn and beans made a good dinner, and the UN planes also supplied us with fishhooks. I went to the Pochala River and caught plenty of fish. I discovered the constants and the variables in the algebra of survival. If I had plenty of food but risked violent death, I felt better than if I had starved in peaceful times. My first rule, every day, was to find enough food to make it to the next day. Then I could afford the luxury of worrying about the enemy.

Often I thought about my parents. Perhaps being once again in my home country brought back their memory. I saw a woman one time in the town who looked and dressed like my mother, and I began to think about my village. When the bombs fell, I remembered the night the djellabas came. And every time I ran into Abraham—he had survived crossing the Gilo without harm, and I met him in Pochala—he reminded me of friends and family in Duk Payuel. Abraham had become one of the caretakers, serving as a surrogate father to a thousand boys. He made sure we cooked our food properly, had our illnesses treated, and maintained our trenches and latrines.

I knew the civil war was drawing closer to Pochala, because the Antonov sorties were increasing and refugees coming into town told tales from other villages. Reliable news was scarce, though. Nobody had a television, and radios were extremely rare. The only radio signal that reached into southern Sudan came from the BBC. I didn’t know anyone who spoke English, so the news broadcasts that occasionally mentioned the Sudanese civil war might as well have been in Latin or some other dead language. News traveled almost exclusively by word of mouth. It took many years for me to learn of the events in my country that plagued the boys of southern Sudan.

The Sudanese government, under military rule and led by Gen. Omer al Bashir, continually pushed to transform the nation into an Islamic state. Bashir’s forces began the largest offensive of the civil war in March 1992, aiming to break the SPLA’s lines of supply and communication in the south. Relief operations based in Kenya and Uganda proved ineffective, as roads leading to refugee camps in southern Sudan fell under the northern government’s control. The United Nations cut back its airlifts as the assaults escalated. Human Rights Watch/Africa reported many abuses, including “arbitrary killing and looting of civilians.” Northern troops burned everything within 12 miles of the newly captured towns of Rumbek and Yirol in an attempt to deny food and support to the SPLA. Those actions alone added 100,000 more people to the list of refugees made home less by the civil war. Meanwhile, internal strife between two rival factions of the SPLA led to additional fighting in southern Sudan, killing thousands of civilians caught in the middle.

The year’s worst fighting occurred in July, when the SPLA faction led by Col. John Garang captured the town of Juba in a massive counterassault aimed at rolling back the government’s southern sweep. Summary executions and torture, including the administration of electric shocks and the crushing of testicles, became common.

ACCOUNTS OF WAR GREW INTO WILD RUMORS. I HAD NO experience of the world outside Sudan and Ethiopia. If someone told me a story about the United Nations or a foreign country or the djellabas, I tended to accept it. Every night, one of the caretakers walked through Pochala shouting the news of the day as he went from one cluster of huts to another. “You’ve got to take care of yourselves tomorrow, because the Antonovs are coming again”—that was one of the messages he shouted a lot. Sometimes the Antonovs came the next day; sometimes they didn’t.

I wondered, like the other boys, about the UN. The people of the UN had to be Christians, I thought, to be helping Christians in Sudan. Other Dinka boys said the UN—they pronounced it “WEE-enn”—had to be stupid to give away so much food and clothing. Or they said the relief planes only gave us the food that the UN deemed fit to feed its cows.

In January 1992, the bombardments increased again, and the caretakers told us to prepare to move out. They said the northern armies had drawn near Pochala, and soon the town would fall into their hands. I wanted to go west, initially to the Kangen Swamp and then on to Duk County. Wiser heads reasoned that if the djellabas could take an SPLA center such as Pochala, they could certainly seize places that were less well defended. In the end, the caretakers consulted with the SPLA and decided to vote. The soldiers urged them to flee from the fighting but not to the land of tribes hostile to the Dinka, like the Murle. The caretakers went off by themselves to decide. Finally, around seven one night, they reached an agreement. They sent out the news, dispatching the town crier.

“We go to Jebel Raat,” he shouted. The words mean “mountain lightning,” hardly the most comforting name for refugees fleeing war. That meant we would walk south, toward Kenya. South, farther from our homes, but also farther from the djellabas.

From Raat, a town controlled by the SPLA, we would keep going to stay ahead of the soldiers. A line of villages stretched south from Raat like beads on a long string: Pakok. Buma. Kapoeta, the largest town in eastern Equatoria. Then Nairus. Finally, at the end of the line, Lokichokio, a town just over the Kenyan border. If we made it to Kenya, we would be safe once again. It sounded easy. In reality, the journey from Pochala to safety across the border measured 500 miles. Unlike my journey from Duk Payuel to Ethiopia, I would travel this time in a pack of thousands of boys, all following well-marked paths through the savannas, forests, and deserts of southern Sudan. Djellabas in airplanes could not miss us if they tried. Nor could the native tribes whose homelands we would have to cross.

“You will leave soon,” the crier said. “Get some food together to start the journey. Along the way, the UN will give you food and water, and you will be okay.”

On the appointed day, I stood with my group, ready to begin walking. We had sewn new carrying bags from pieces of tent canvas and emergency medical bags the UN had dropped on us, and we filled them with maize, beans, and plastic bottles of vegetable oil. Everyone carried enough food to last several days. Like the other boys in my group, I had sewn shoes out of plastic bags and rectangles cut from tent coverings. They looked strong, but they fell apart after only two days’ march.

We set off on a morning at the end of the dry season. We sang to keep our spirits up, for we did not know what lay ahead.

I sang in the Dinka language:

Lord, bless our journey,

Give us joy and peace.

Let the love of your word be our victory,

And take our fatigue away.

As we go through this wilderness,

We thank you and worship

Because your words we have listened to.

Help us believe in you in our heart and life,

Now and forever and ever.

We sang other songs, too, to be brave and to break the tension with humor. One boy sang his own song, “I am malaria,” which meant, “I am strong; I can hurt anybody.” Another boy sang to tell the world he was a lion. Some walkers sang about the men going forward and the women being safe; perhaps 500 women and girls, refugees from their villages, marched with us.

When I saw a boy by the side of the road, apparently resting, I chided him for not marching with us. “What are you doing? Are you a woman?” That was an insult to a Dinka man. The boy replied, “No, I am waiting for somebody.” He could not admit he was resting if he wanted to keep his self-respect.

Most boys walked with heads held high, boastful and strong, because that’s how we felt. The heat of early March enveloped us like lava, but we did not feel it. We strode southward with pride, because we moved on our own volition, not at the barrel of any djellaba gun. Caretakers walked with us, on both sides of a two-track Anyuak path, to make sure we did not disappear into the grass or fall behind.

The air felt dry, and the parched ground gave us good footing. The Anyuak had set small fires in the forests around where we walked, to clear the brush. Like the Dinka in Duk County, they wanted to open up the ground beneath the canopy so they could hunt for big game. The grass and brush was so dense that if the Anyuak hadn’t cleared it, they could have stood within ten feet of an elephant and not known it. Ash from the fires drifted down on my head as I walked, like gray leaves falling from a tall tree. Smoke and fog mixed in the morning to enclose the path within misty walls. At night, I could see the Anyuaks’ fires burning in the distance.

Caretakers had briefed our group before we began walking to be alert for large predators, but I did not see any. Two boys who straggled at the end of the line did fall to Anyuak arrows, though. The news spread through the line, from mouth to mouth, and we picked up our pace.

After about two weeks, the head of the line reached Raat, but it took three more days for the last of the marchers to enter the village. I stayed in the town for three days. We had eaten most of the food we had brought with us. My group moved out when it was our turn, but others kept coming. I doubt the village could have held us all at the same time.

And so we came to the next village, Pakok. There we found Ugandan rebel soldiers who had crossed the border to find sanctuary in Sudan. What a crazy world—each country in revolt, pushing its rebels to seek sanctuary in a neighboring country that was in turn dealing with its own problems.

We also found yams, maize, and groundnuts in Pakok. Whatever we had to barter with, we traded for food. We stayed there for some time, because food was so abundant.

We finally left for Buma at the end of March, confident that the UN would bring us water and food on the long journey. Our caretakers had told us so. I did not know that Red Cross relief workers had delivered food and water to previous lines of boys making their way toward the Kenyan border, or that the Khartoum government had evicted the Red Cross for a few months, accusing them of assisting the SPLA.

I TRUSTED IN THE LORD AND BELIEVED SOMEONE, SOMEWHERE would help us. We felt so strongly that we would find assistance in the wilderness that my group used most of our water supply more quickly than we should have. Some we drank, and some we used for boiling beans and cornmeal.

I remember a blindingly clear day, with so much sunlight that it hurt to look at the sky. It was the middle of the hot season in southern Sudan. The call of a crow seemed to carry forever in the still air. A few cirrus clouds, impossibly high, barely moved as the sun crawled from east to west. I marched in the heat and drank my water until it nearly ran out. I wiped the sweat from my forehead with my fist. That night, my group pooled our beans and cooked dinner. We used the last of our water; I assumed we would get more from the UN the next day.

Come the morning, the sun rose angry and hot as we stood and started walking again. Around noon, some of the smallest boys began crying because of heat and thirst. My feet started to burn on the dirt path. I noticed some of the boys around me leaving the path and walking through the grass, where the ground had a bit of shade. I stopped and bent my knees to examine the bottom of my left foot. The skin had turned red, and my toes had swollen with fat blisters. I popped one of the blisters, and hot water ran across my foot. It hurt like a bee sting. I checked the right foot, but it was not as bad. I tried limping for a while by putting my weight on my heels, to keep the dirt out of my open blisters, but that proved very awkward. So I took off my T-shirt and tied it around the toes of my left foot. It didn’t help much, and I couldn’t get traction on the dirt. Finally, I tore the sleeves off my shirt and tied one sleeve around each foot. I saw other boys doing the same. It helped for a while. Then my feet started to hurt again. I checked my right foot, and blisters had formed on those toes, too.

I could barely walk. I looked for Abraham to help me, but he was nowhere to be found. I hobbled as best I could; I did not want to fall to the end of the line and get captured or killed by the Anyuak. Dripping with sweat, pain, and exertion, I kept moving forward, hour after hour.

At last I stopped. All of my blisters had burst along the way, and I felt woozy. I tried to forget about the heat and my dry throat, but I could not. All around me, other boys cried for water but got none. Too tired to care, I fell asleep right beside the road. For three hours, people tramped by a few feet from my head, but I did not stir. When I woke up, feeling a little better for the rest, I fell into line and started walking again.

Things became really bad. The sun hammered us from above. Boys tried to urinate, but nothing came out. They walked from person to person, holding out their cups and begging for someone to pee a little bit so they could drink it. A few boys could still urinate, and they obliged some of the beggars. I begged, too.

I didn’t find anyone who could help. I envied the boys who had a cup of urine to drink.

I staggered forward, not sure how far I could go. Then, I saw a miracle. A UN water truck came toward me, following the two-track path. Boys stepped into the grass to make way. “Here comes salvation,” I thought. But the truck did not stop. It passed me and headed for the end of the line. For once, being last, where the Anyuak and wild animals could pick off stragglers, had its rewards. A few boys tried to jump in front of the truck to make it stop, but the caretakers pulled them away. Suddenly, the marchers realized that the fastest way to get water was to double back. Hundreds started retracing their steps, heading for the end of the line, afraid more of dying of thirst than of Anyuak and lions.

I caught up with the water truck and got my drink. It tasted wonderful.

From that day onward, the UN returned every day as we walked toward Buma. The relief workers knew our route and met us in the afternoon. Always they came in one water truck and one Land Cruiser bearing the blue UN flag. No more did we crowd toward the end of the line. We kept walking forward, stopping to dunk our heads in the mobile water tank when we came upon it. The caretakers timed us. I stuck my head underwater and took a big gulp. After a few seconds, I felt a hand on the back of my neck, pulling my head free. That was the caretakers’ signal to move along and make way for another boy to dunk and drink.

The UN trucks also delivered bags of food, which the trucks deposited by the side of the path. We got spoiled by the steady drops. We always carried food from the night before, but as soon as we saw the new food we cast off the old. In about a week, following our daily routine, we arrived in Buma.

The SPLA controlled the town, but the Murle controlled the surrounding forest. On our way into Buma, the Murle captured one of my cousins, Aleer Kongoor Leek, who had strayed off the path. They didn’t kill him. Instead, they tried to make him into a Murle child. The more children a Murle family has, the more powerful it becomes and the more cattle it can claim in its recurring cattle raids. My cousin broke free several months later and rejoined his group. He told us three Murle men had fought to take possession of him. They took him to Murle land and gave him to an old woman. Her son had been killed in one of the wars, and she had no surviving children. She tried to make him eat snake without telling him, because anyone who eats snake forgets his family and is ready to join a new tribe. But Aleer found the snake bones in his food and refused to eat. For six months, he was forbidden to go outside and play with the Murle boys, so the adults could watch him closely inside their huts. After a while, Aleer said, the Murle men began his training. They took him to the forest and told him to hide. Then they went looking for him. Whenever they found him, they beat him, he said. Aleer got better and better at hiding in the forest, which is characteristic of the Murle. He learned to anticipate where the Murle men would move by watching their eyes. He learned to run long distances with one leg tied behind him, in order to prepare for the possibility of being wounded but not killed. He carried Murle boys great distances, to prepare to help comrades injured in war, and he became quite strong. The Murle began to trust him. Since he never ate the snake meat, however, he remained a Dinka in his heart. One day, when he went far into the forest, he ran away and made his way back to camp.

I stayed in Buma for about a week. During that time, news reached us that the djellabas had captured Pakok. The UN truck drivers said we would be safe for now, but we itched to get moving again, in case the Arabs were not far behind us.

We set out again, bound for Kapoeta. The natives we met along the way were Taposa. Their women wore an animal skin on their back and another on their front, and no other clothes. The men stayed naked. The Taposa disliked the long line of boys, whom they saw as invading their land, and I think they sought to curry favor with the djellabas by harassing us. While I rested under a tree near the path, I saw three Taposa moving in the brush. They started shooting, killing one boy and wounding another. A couple of boys picked up their wounded friend and carried him until the following day, when the UN car arrived and they put him in it.

The northern government’s Antonovs found us and began bombing us again, but I think the Taposa frightened me more. They wore scars on their arms or their chests, one scar for every man they had killed. It was rumored they killed for fun. One day on the road between Buma and Kapoeta, we passed through a tiny Taposa village. Everyone was dancing. They had just returned from a war with the Murle. Three of the dancers held out the heads of Murle men they had killed. They jumped and shouted and shook the heads. It was very scary, but they did not harm me that day as I passed through.

Finally we approached Kapoeta. The djellabas had bombed the town not long before my group, which was third in line, came near the northern outskirts. Everyone was frightened. One of the caretakers had a radio and understood English. He tuned the dial to the BBC’s “Focus on Africa” and listened to a news report. It said the northern soldiers were closing on the SPLA base of Kapoeta from the east. We figured the soldiers probably would arrive in three days. The broadcast also gave the world one of the first glimpses of our plight. “Twelve thousand boys”—the reporter probably had undercounted the total—“are on their way on foot through southern Sudan to escape the war.”

THE REGION AROUND KAPOETA WAS A NEW AND FORBIDDING landscape. The dirt changed from black and fertile to red and dusty. The wind blew constantly through the moonscape of the Tingilic Desert, making a whistling sound though the achap trees that I saw for the first time. Achap grow only about four or five feet tall, and typical of a desert shrub it has thousands of thorns, nasty and curved like fishhooks, instead of broad leaves that can release precious water into the air. Groves of achap crowded both sides of the powdery trails outside Kapoeta. If achap thorns caught a walker’s shirt or pants, he could never get them free without tearing the clothes. I saw boys get snared by achap, struggle for a while, and then give up and take off the clothing. The Taposa had learned to adapt, however. They crawled through the achap groves and sought refuge in their shade by first covering their arms and legs with animal hides. They hid among the thorns as we passed. Then, they collected the food we had left behind, and sometimes attacked the last ones in line.

The day of the first Taposa attack, a boy in my group became very ill. We had eaten beans for dinner the night before, and they had not been cooked properly. I had only a handful, but this boy had eaten too much. The gas in the beans made his stomach swell like a beach ball. He inflated to such a large size that he could barely move his arms and legs, which stuck out from his torso like tree limbs. I gave him a homemade remedy for intestinal gas, making him drink soapy water and then having him suck on a scrap of soap. I thought the treatment would clean out his insides, but the soap had no effect. He lay flat by the side of the achap groves, moaning and complaining that he was in too much pain to move.

I didn’t know what to do. I was thinking about other treatments when—boom!—a hidden group of Taposa fired a volley of gunshots into the line of boys on the trail. Boys ahead and behind me began running. I panicked; I had to get my group out of there, and quick. I hit the boy’s distended belly with a stick, trying to force the air out of him. He merely cried in pain.

“This is the end of my life! I’m going to die,” he whimpered.

“Stop!” I screamed at him. “Get up. We have to go.”

The boy tried to sit up, but he couldn’t get his balance with his round belly. He wobbled and lay back on the road.

I was a leader of my group, and his safety was my responsibility. I could not just leave him. I rounded up a couple of boys who had not run away, and we tried to roll the round boy along the ground, rotating his enormous belly like a ball. No good—it was too slow and too awkward, and no doubt uncomfortable for the boy. We tried to make him defecate to shrink the swelling, but he cried, “I can’t do it!”

I got out a blanket and fetched two wooden poles. I set the poles parallel on the ground and tied the blanket between them to make a stretcher. We rolled the round boy onto the stretcher, and another boy and I hoisted it onto our shoulders. A third boy carried our food rations. The stretcher swayed left and right as we walked. Each jerky movement put the round boy in agony and taxed our strength.

“Stop swaying!” he yelled. “It hurts!”

But we couldn’t stop. We had to get him away from the Taposa. We carried him for perhaps a half mile before we had to put him down and rest. When we started again, falling in line with the never ending stream of boys, I took a turn carrying our food and another boy shouldered my end of the stretcher.

We came to grove of achap trees. A few Taposa warriors stood among the achap, not afraid to be seen. We approached apprehensively. The Taposa watched us and the rest of the boys in line. Just as my group was about to pull even to the Taposa, they aimed their guns and fired into the air above the line of boys just ahead of us.

I let go of my food bag, and the boys carrying the stretcher dropped the round boy from shoulder height. Everyone except the round boy ran away, dodging achap thorns as we looked for a place to hide in the bush.

I didn’t expect the round boy to be alive when we quietly returned a few minutes later, but there he was, still on top of the blanket. The Taposa apparently didn’t want to kill him or anyone else; they only wanted our food. All of the bags we had dropped in our haste had disappeared, along with the Taposa.

As we gave thanks for our good fortune, we saw a UN car approaching. The driver didn’t stop, passing us without a glance at the round boy on the ground. The round boy said he would try to walk, but he still could not even sit up. He threw himself flat and said he would die if the UN car did not return to pick him up.

Fortunately, the car did return from the back of the line. As it drew even with us, I waved and pointed to the round boy on the ground. The car stopped, and two men got out. One of them, a Kenyan, took a look at the boy. He went back inside the front of the car and emerged with a white tablet, which he put in the boy’s mouth. Then he and his companion lifted the boy into the car and drove off.

I found the round boy at Kapoeta. He felt better, and the swelling in his belly had subsided. We called him Man Who Ate Beans, but it became something of a misnomer. He refused to eat beans, ever again.

Other refugees had come to Kapoeta before us and stayed long enough to begin formal schooling. SPLA soldiers acted as their teachers, drilling them in their ABC’s in the open desert air. One soldier told a visiting journalist he considered the young boys who made it to Kapoeta to be among the most fortunate in southern Sudan. “I call them the lucky boys,” he said. “They are lucky because we give them education. To us, a classroom is a tree that brings shade.”

Lost Boys wash themselves in a half drum at Kakuma in 1992,

when the camp was little more than fields and achuil trees.

I stayed only three days in Kapoeta. I arrived in May, just ahead of the northern offensive. Caretakers told us to move on, and we headed south toward the next town, Nairus. In the middle of the night, the SPLA soldiers awakened the relief workers in Kapoeta, including representatives of the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), and urged them to evacuate toward the Kenyan border. On May 28, a few days later, Kapoeta fell to the northern soldiers, cutting the main road into southern Sudan. Airplanes flew overhead and occasionally bombed us as we hurried toward Kenya.

The Taposa met us as we came to Nairus. They offered to sell us milk from their cows, goats, and sheep. I traded some of the UN food for a glass of milk. It was the first real milk I had had since leaving Duk Payuel four years earlier. I’m not counting the powdered milk I drank in Pinyudu. I saw a Taposa woman milking a cow and asked her to give me a drink. It was so, so good.

Not all Taposa greeted us so warmly. They liked our UN food, and a couple of times they kidnapped a boy and held him for a ransom of beans and vegetable oil.

The caretakers hadn’t originally planned to move us over the border into Kenya. We had hoped merely to go far enough in Sudan to escape the fighting. But the djellabas seemed bent on chasing us wherever we went, from Pochala to Buma to Kapoeta to Nairus.

Each town fell to the attacking soldiers, yet no matter how many towns and cities they conquered, they could not defeat the SPLA in the countryside. Garang’s forces gave battle when they thought they could win and avoided it when the odds were against them, all the while biding their time.

I hoped to stay for a while in Nairus, and I did—for about two months. Then the northern soldiers approached the town and stepped up their air raids once again. I dug another trench, like the other boys, and dived into it every time I heard the Antonov engines overhead.

The planes came every night. One evening, we heard an especially long and loud bombardment in Nairus. A rumor spread through the streets: “The djellabas may come tonight.”

“Time to go,” I thought.

The caretakers agreed. Some of the bombs had landed in the city and killed a few boys. The town had several thousand permanent residents, and the arrival of so many refugees had doubled its size without doubling its housing. Sleeping boys crowded the streets at night, making temporary shelters of tree limbs and blankets. They were easy targets for well-placed bombs and shells. One morning, everyone set out on foot for Lokichokio, just inside Kenya. The town served as UN headquarters for all of East Africa, so we felt we would be safe there. The United Nations would feed us and keep us safe from the war.

The walk to Lokichokio took only about a day. We crossed the international border without recognizing having passed any magic line. Our spirits felt lighter for our new freedom, yet sadder too for leaving our homeland. We carried no water, expecting once again for the UN to provide for us. When we finally got to Lokichokio, we did find some water that the UN had left us in a drum. A UN representative greeted us as we entered the town. He was so rude—he dipped his hat in our tank of water to rinse it. Perhaps he did not know it was our drinking water.

Around this time, the SPLA renewed its push to recruit soldiers from among the refugees. Abraham decided to volunteer. He got a new khaki uniform, black boots, and an AK-47 assault rifle. Morale soared among the recruits as they danced and jumped and sang songs that inspired courage. Every morning around four, Abraham and the other new soldiers fell out for training when the SPLA whistled. Everyone ran and sang until daybreak.

Lots of people, especially caretakers, volunteered. The SPLA chose the ones who looked strong and healthy. Some of the shortest young men wanted to join so badly they stood on folded sacks to make themselves look taller as the recruiters walked along to choose the most promising prospects in the lines of volunteers. I tried to join, too. “Now is the time to fight,” the caretakers had told us, and I believed them. I wanted to go with Abraham. I liked the look of the uniforms and I thought I might kill some of the enemy before they killed me.

But the recruiters dashed my hopes. They knocked me out of line, rejecting me without giving a reason. I suspect I looked too skinny and weak, and they feared I would die even before I got to the combat zone. With great sadness, I watched Abraham march off to war without me.

Abraham Deng Niop: When we got close to the Kenyan border, I left the Lost Boys and joined the SPLA. That was 1992. From that time until 2001, I fought with the SPLA, in many places and in many battles. All that time, while John remained in Kakuma, I did not hear about him. Then, in 2002, I learned he had traveled to live in the United States. Some of the Lost Boys who had gone to America had talked to people in Kenya. I went to Kenya in 2002, and I talked to people I knew, and I asked them about John. They gave me John’s phone number, and we got connected again. That’s how things worked—people know other people and their families, and they ask around until they find the ones they are looking for.

John and I talk on the phone a lot. We talk about what John is doing in America, at the university, about what I did in the SPLA. About family issues. About life.

John urged me to go back to school. I live in Kampala now. The schools are much more expensive in Kenya than in Uganda, so I am studying in Kampala to get the equivalent of a high school degree in computer engineering. John has supported me by sending me money for my tuition. I hope to finish my degree and go back to Sudan, to Duk Payuel, to settle into life there again.

I stayed in Lokichokio for two months. Then the UN decided to relocate all of the boys to a new refugee camp that the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees was organizing at the tiny town of Kakuma, 74 miles from the border. At the time, Kakuma consisted of two buildings in the middle of the desert, with almost no green thing growing nearby. With a little help, I made it in one day. The United Nations sent open-topped trucks to transport the boys to Kakuma. About 50 rode at once, standing shoulder to shoulder on the truck bed like farm animals. I stood by the edge, so I kept my balance by holding onto the side of the truck. Those in the middle were less fortunate. The Kenyan driver zoomed along, and the truck swayed back and forth as he made turns or hit bumps in the road. The rocking knocked most of the riders in the center off their feet. Boys in the front of the truck bed hammered with their fists on the roof of the cab to tell the driver to stop or slow down. Most of the time he ignored the noise.

As the boys tried to keep from falling, they grabbed onto nearby arms, necks, and clothing. Boys lost their shirt buttons to hands snatching at any available clothing. Fights broke out among boys who tore each others’ shirts. One boy clutched at another’s shorts as the truck jerked, and the unfortunate boy found himself naked, his pants around his ankles with no space for him to bend over and pull them up. He recovered his shorts—and his dignity—only after the truck stopped and everyone piled out. By that time, red dust kicked up by the tires coated everyone on the bed. All I could see were eyeballs looking out from suddenly unfamiliar faces. It might have been funny if some of the boys hadn’t suffered injuries in the jostling.

That was my first ride in a car or truck. For the first time, I moved faster than the thiang or the lion, and I glimpsed a vision of the modern world: fast, blurred, and chaotic. My eyes burned and shed tears from the wind in my face. The speed also made me dizzy as I tried to keep my balance and comprehend the world zipping by.

I made the trip with a bundle of sticks that had been my hut in Lokichokio. Others did the same. I tied a green, ropelike piece of clothing to the bundle to show it was mine.

WHEN WE ARRIVED IN KAKUMA, THE CAMP ON THE ARID PLATEAU of northwestern Kenya seemed the end of the Earth. Every night, the wind blew in off the desert and deposited red dust over everything and everyone. I woke up my first morning in camp and didn’t recognize myself or anyone else. We all looked like a different race: red black men. Cars that drove into camp in the middle of the day kept their headlights on to try to cut through the clouds of grit and the whirling dust devils that danced across the campground. When I tried to walk across camp, my legs sank to the knee in fine red particles.

Red hills surrounded the camp, and dry riverbeds lined the low spots on the dusty plain. The temperature nearly always hovered around 100F. The camp had no electricity, no latrines, no running water, none of the things to make life easier for the thousands of refugees who began scattering across the site.

The Kenyan government and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees began expanding and improving the site for the camp in 1992, as soon as the first boys from southern Sudan arrived from Lokichokio. Kenyan immigration law required incoming refugees to live in such camps, and it forbade us to work for wages in Kenya. Thus, I and the other boys became dependent on donations to keep us alive. By settling into Kakuma I had made a leap of faith just as surely as I had when I jumped into the surging Gilo River.

The day we arrived, only a few gray skeletons of trees grew at the camp, so it was good that we had brought hut-building materials from Sudan. We boys began assembling huts of mud and sticks, with grass-and-leaf roofs, much like our homes in southern Sudan. Three to five boys shared a hut, and we grouped our huts by tribe into a few dozen. That helped foster a village feeling in camp. I threw together my first hut from the materials I had brought with me. The floor was bare dirt. It may not have looked like much, but for a boy who had spent most of a year on the move and constantly alert for air raids, it seemed a castle. Even better, there were no mosquitoes in the desert air.

Soon after I arrived, God blessed the camp. The rains came, and the rains stayed.

The dust settled and formed cakes of mud. The desert achuil trees soaked up the moisture and started to sprout tiny green leaves. They spread their branches and touched the limbs of other trees, like boys holding hands. The Turkana, the native tribe, were amazed. “These Dinka come with rain,” they said. It sounds odd to say so, but the Turkana, a desert people, did not like it when it rained a lot. They had no permanent shelters to keep them dry. Their homes consisted of large sheets of paper tied atop lashed poles made of achuil wood, so the rains made them miserable and wet. They lived all the time with famine and drought, and so felt understandably jealous of the food the UN had given us.

In the first few weeks at Kakuma, I tried to make friends with the Turkana. I traded some of my food for their firewood and milk. But they still never had enough to eat. When I ate dinner, I could feel their eyes watching me. Those times, I gave them a little of my food. They seemed old even when they were only in their 30s and 40s.

UN workers dug down to the water table and opened a permanent well. It was the cleanest water I had ever tasted. They put chlorine into the well to kill any lingering bacteria. Of course, I did not know about bacteria at the time. Everything I had drunk at Duk Payuel, Pinyudu, or on the road had been standing, stagnant water.

I felt blessed. Shortly after arriving in Kakuma, I began attending “synagogue” every evening around sundown. An Episcopal priest, John Machar Thon, named our camp’s nightly Christian worship services after the rituals of the Israelites, who fled with Moses out of Egypt and gave thanks in the wilderness to the Lord.

Like the Israelites, he told us, the Sudanese had fled again and again from persecution and yearned for their homeland. He said it would be fitting if we worshipped as the Jews did when they wandered in the desert, and if we tried to live as they lived. Thus, the refugees in Kakuma formed “synagogue” groups to worship, sing, and pray at night to bring us closer together, as well as closer to God.

I belonged to a group of about 75 boys, who gathered for two hours every evening. We sang in Dinka. Sometimes we knelt and prayed, sometimes we felt the spirit moving us to prophesize, and sometimes we just held each other. We jumped and clapped hands. And we danced. Ours was a demonstrative, emotional synagogue. It was the sweetest thing when I felt the spirit of the Lord moving through me. It was like drinking cold water on a hot day. I knew the Lord had kept me alive in the desert and in the forest, and I was sure he must have a plan for me to do something good with my life.

Settling into Kakuma, so far from home and so destitute of possessions and power, I could only begin to imagine what that good thing might be. All I could do was prepare myself for whatever God would send my way.

To do that, I knew I had to embrace my new mother and father: the classroom and the book.