6

ACCULTURATION CAME EASIER FOR SOME LOST BOYS IN AMERICA than for others. A New York Times reporter watching the arrival of a group of Lost Boys in Boston said one screamed and fled in fear at the sight of an escalator. Another rode in a car through the woods to get to his new home and asked the driver, “Are there lions in the bush?” Similarly, John Dau and his roommates hesitated to swim in blue-green Skaneateles Lake until they received assurance that it held no crocodiles or hippos.

“For them, everything is new,” a letter from the Skaneateles First Presbyterian mission committee explained to the church congregation. “They are wide-eyed and full of wonder. They are like sponges in this new environment. They are almost childlike, most never having had a childhood. They need parenting and guidance, and [they] accept their sponsors in this role. They are very polite and respectful. Dating and marriage is of great concern to them, and they have had no education in these areas. Their cultural background is very different from ours…. When you meet them, you will feel you have been given a gift that you would not receive upon meeting another American.”

One of the biggest transitions for many Lost Boys centered on the sudden freedom and self-sufficiency. Refugees in Kakuma had been handed many of life’s necessities. In America, a totally foreign land where water, the most basic requirement of life, had to be purchased before it flowed from faucets, rained down from showerheads, and froze solid in boxy kitchen appliances, the Lost Boys needed to find jobs as soon as possible. Many started out doing menial tasks in factories and fast-food restaurants.

Health insurance, Social Security deductions, income taxes, traffic regulations…the rules that governed basic survival overwhelmed the newcomers. Beyond them lay the folkways and mores, some subtle and some not so subtle, that made social life pleasant or uncomfortable. How often do Americans bathe? How should men treat women at the workplace? How do Americans handle the issue of race? How could Lost Boys make new friends? And why do Americans stay all by themselves in their rooms at night, instead of gathering for time together? Lost Boys often learned lessons the hard way. Two of them in Kentucky chatted with an American woman who had been married for seven years but did not have children. One of the Lost Boys asked, “What is wrong with you that you do not have a child? Is it your problem or is it your husband’s problem?” The other Lost Boy, more worldly than his companion, admonished him that the reason a married couple did or did not have children was a delicate subject in America.

Lost Boys occasionally got into trouble with the law. Most scraps were minor, but Boston authorities charged one resettled Sudanese with rape. Lost Boys also became victims. One died in Atlanta in a drunken dispute over ten dollars that resulted in charges being filed against another Lost Boy. Others suffered violent deaths in Nashville and Louisville. In 2006, Lost Boy David Agar was shot to death in a scuffle with an armed robber outside a bar in Pittsburgh, five years after he arrived in America as a teenager. According to the Pittsburgh Post-Dispatch, Agar planned a career in video production and a reunion in America with his mother, who had turned up in a refugee camp after he arrived in America. “By all rights,” the paper said, “Mr. Agar’s first 18 years of life should have granted him immunity from such senselessness.” Friends described Agar as quiet, gentle, friendly, religious, and profoundly keen about the fortunes of the Pittsburgh Steelers football team. In short, not so different from a lot of Americans.

I DREAM OF AFRICA ALMOST EVERY DAY.

Sometimes I dream at night that I am back at Kakuma or walking with Abraham along the path from Duk Payuel. Sometimes my mind wanders while I work at the hospital, and I see things that are not really there. For some seconds, I do not remember where I am. Then I snap out of it, and I am back in Syracuse.

Over and over I have variations of the same dream. Soldiers want to kill me. Lions want to eat me. I shake and wake up. And I ask myself, “Who am I?”

Most of the time, I can’t remember the details of the dreams. But I remember one with clarity.

In my dream I sit atop an eight-foot-tall anthill and watch over my father’s flock. As I perch there, I make toy cows out of clay. Beside me lie my knife, my stick, and my spear. I am chewing a sorghum stem and looking at my clay cows, when all of a sudden I hear something running. The curtain of grass opens, and I see a goat of mine, followed by a lion. The lion chases the goat around and around my anthill, and I think that perhaps the goat has run to me to get my help. I get up, grab my spear, and point it at the lion. The lion bows down, afraid of me, and freezes. I seize the lion by the tail and swing it around in a circle. I am so, so powerful. Holding the lion’s tail like the handle of a whip, I beat the animal’s body against the anthill. Still the lion refuses to move. I switch to my stick and beat the lion’s head, then return to swinging it by the tail and whacking it against the hill.

When I look up from beating the lion, I see a group of boys having fun. I drag the lion to where the boys are playing. The boys ask me, “Why are you killing that lion?” I say, “If I kill this lion, he will not be able to attack my goats again.”

We talk like that for a while. In my dream I stand like a Dinka boy on watch, with my right leg straight, my left leg bent at the knee, and the handle of my spear tucked under my shoulder, its point stuck in the ground like a third leg.

“What do you want to do with that lion?” one of the boys asks.

“I want to throw it away,” I reply. “I will take it far away and get rid of it so it cannot harm anything in my village again.”

I take the lion to a place where I can cast it into a swift-flowing river, where the current will make it disappear. Just as I start to toss it in, though, it comes alive and stands up. In the blink of an eye, it grows strong again. The lion chases me, intent on catching and eating me. I run very fast, until I trip over a bunch of grass and fall. The lion leaps toward me…and I wake up.

I don’t know what the dream means. Certainly I am no Sigmund Freud, whom I have read about in one of my classes. I never had to kill a lion, having only chased hyenas from the farm when I was young. But I wonder. My dream is about protecting the things I cherish from a powerful force coming in from the outside. And just when I think the force has been subdued, it rises anew and threatens me. Now, I suppose I could be the lion—my name Bul means “lion.” But more likely, I think, the dream would make sense if the lion wore a djellaba.

Some of my friends among the Lost Boys have nightmares. They see their loved ones killed by bullets and shrapnel or seized by the roiling waters or the crocodiles of the Gilo River. How long they must relive the horrors of their childhoods I do not know. They have come halfway around the world, thousands of miles from their African homes, yet they cannot leave Africa behind. Nor should they, I think. They, and I, must learn to be Dinka in America. With God’s grace, we must learn to treasure the best of our experiences and apply them to our new lives. We must keep moving forward. When a man finds himself in the middle of a swamp—be it a literal quagmire or a figurative one, like drugs, divorce, or despair—going forward is the only way to get free.

I know my way out of a swamp. I must educate myself. I must provide for my loved ones. And I must make sure that I do all I can to help my people, in Sudan and in America.

Since 2004, I have taken on added responsibilities. They have complicated my life but also brought great gladness.

ALMOST FROM THE DAY I ENTERED KAKUMA IN 1992, I TRIED to find my family. I wrote about 70 letters and gave them to the Red Cross. The agency sent tens of thousands of messages from the Lost Boys in Kenya across the Sudanese border to try to reunite families. Some of the Lost Boys had success through such methods, and I was willing to give it a try. Nothing came from my letter-writing campaign. Still, I did not give up hope. When I got to America, I learned that it often took years for families scattered by Rwanda’s civil war of 1994 to find each other. For that matter, American newspapers and television broadcasts still occasionally carry stories of the reunions of European families scattered by World War II. Surely in America, where I had my own phone and access to the Internet, I could search more effectively for my family than I did in Africa.

Two days after arriving in America, I wrote letters to my friends in Kakuma. I told them how good I found life in America, how the country flowed with milk and beef, and how well Susan Meyer and her church friends had treated me. Susan took the letters and mailed them for me.

One of my Kakuma friends who received one of my letters traveled to Uganda for a while. He told the people he met about the Lost Boys in America, and in particular he mentioned his friend, John Dau in New York. That placed the message on the traditional news medium of the Dinka, the storytelling chain that spreads information from person to person, until it reaches the farthest corners of the county.

A man living in Uganda whose name was Goi heard the news and became intrigued. Goi asked my friend, “Who is this John?”

“It is John Dau, from the Nyarweng clan,” my friend said.

My friend did not know Goi was my brother. By the longest of odds, at a camp hundreds of miles from any place I had ever called home, two people I loved came together to pass along the most improbable of messages.

Goi went home and told our mother, “I found a man who talked about a Nyarweng named John Dau today. He said John is alive.”

“No,” my mother told Goi. “John is dead.”

Goi decided to get more information. He went back to my friend and started peppering him with questions. What did this John look like? Where did he come from? What was his father’s name? When did he go to America? What did he say about his life before he became a Lost Boy? Goi also volunteered information about the shelling of Duk Payuel in 1987, and how the family got separated that night.

John, in a dark suit, stands with his brothers Goi, right, and Aleer, and Angok Ayiik, the wife of his half brother, in Uganda in January 2006.

They compared answers and thought there were too many coincidences. Goi invited my friend to his home to meet Abraham Aleer Deng, our eldest brother. Aleer heard the evidence and decided to write to the return address on my letter.

When I got home from classes at Onandaga Community College on October 18, 2002, the sight of the big letter in the apartment mailbox sparked my curiosity immediately. Ugandan stamps covered the back of the envelope, and the words above the handwritten address said, “Dhieu Deng Leek,” a name I had not used in a long time. I took the envelope inside my apartment and opened it with trembling hands. Out spilled a letter and photographs of an old man and woman. They looked like my mother and father, only grayer and more wrinkled.

“John,” Aleer wrote, “if you are my brother, please, can you write to us? And if you are not my brother, please throw this letter away.”

It sounds like a cliché, but I literally jumped for joy. Two sentences into reading the letter, I held it up as if it had been a thousand-dollar bill. I bounded around the tiny living room like a jackrabbit.

“We are still alive—mother, father, and all of your brothers and sisters, plus a sister born after you left, named Akuot. Unfortunately, our three uncles were killed in the shelling, along with their families.” The letter went on with news of how the family had settled in a camp along the Sudan-Uganda border. It ended with a Ugandan phone number.

I called Susan Meyer. I called Brandy Blackman. I called Jack Howard. I called the InterReligious Council of Central New York, the agency that had sponsored my resettlement in America and set up my contacts with First Presbyterian Church in Skaneateles. I couldn’t call enough, fast enough, to tell everyone. At church on Sunday, I announced that my loved ones lived, and I had been given a great blessing.

“Be happy with me,” I said. “I have found my family.”

I wrote a letter to my parents and mailed it. Then, after waiting enough time to make sure the letter had arrived, I followed up with a call. Ron Dean, one of the members of Living Word Church in Syracuse, gave me a plastic telephone card charged with $30, good for several hundred domestic minutes. At the exchange rate of 11 minutes of American calls for each minute of connection to Uganda, it gave me only a little while to talk. I had precious little time to reestablish the ties to my family after an absence of 15 years.

The phone rang in Africa. I heard the receiver click as someone picked it up.

“This is Goi.”

“Hello. This is John.”

Goi handed the phone to Aleer. We spoke just a few words, enough to learn that Mother was in the kitchen, when the connection got cut off. I tried calling again but got nothing. The call simply would not go through. I looked at the clock: one in the morning my time. I decided to wait until morning and try again. At dawn in Syracuse, as the sun sank in Uganda, the phone finally rang again at my mother’s house.

I spoke to my brothers first. I filled them in as quickly as I could on my journey of survival with Abraham and my many years in the Ethiopian and Kenyan refugee camps. I told them how I had come to America, gotten a job, and started college.

Goi and Aleer started crying. I cried too. But when they tried to hand the phone to my mother, she refused to speak to me. She accused Goi and Aleer of lying to her, to try to make her feel better.

“Mother, mother, weep no more. It is I, John.” I wanted so much to tell her those words. She would not listen. She would not even allow herself to hear.

I spoke to Goi and Aleer over a crackling transatlantic telephone connection. They relayed my words to our mother, who stood nearby. It must be a trick, she said. John died in 1987. Of that she was certain. She wouldn’t take the receiver from my brothers, who urged her to speak into the mouthpiece.

“Tell Mother, it is me, John,” I said.

I heard a muffled exchange as Goi and Aleer spoke to my mother. Then, Aleer’s voice came back on the line.

“She said, ‘You guys are lying to me. That is not my son.’”

That was the start of 48 hours of agony. I could not get my mother to talk to me, and I could not be sure when the minutes on my card would run out. With a heavy heart, I said good-bye to my brothers and hung up.

Two days later, with a fresh phone card, I tried again.

This time, my mother reluctantly accepted the phone from Aleer and Goi. I pressed my case.

“Mother, this is John. I am the one.”

“No,” she said. “You are not my son.”

She must have had begun to have a change of heart, though, because she decided to test me. Among the Dinka, mothers give their children a variety of nicknames. Few outside the family know what they are.

“If you are my son, tell me the other names I used to call you,” she said.

“Did you call me Makat?” I replied. “Did you call me Runrach? Did you call me Dhieu?”

Makat means “born when people are running away,” Runrach means “bad year,” and Dhieu means “cry.” My nicknames referred to my being born during the year when a raid by the Murle tribe killed two of my father’s brothers. For a split second, silence filled the space between us. In certain critical moments in my life, I have found that time expands until it consumes the universe. I lived a lifetime waiting for the silence to end.

Then, my mother’s voice.

“It is you! But your voice seems different.”

“I’m not the 13-year-old you used to know,” I said. “I’m now a grown man. Today, I’m tall.”

We spoke awhile longer, but I felt my mother still had doubts. I decided to settle them once and for all. I sent her money from my job to help pay the medical bills of my oldest sister, Agot. First Presbyterian Church of Skaneateles sent money, too—$300 from the congregation and $700 from Penny and Bill Allyn. No one would be so generous without a reason. My mother realized the news had to be true. I called her two or three times a week from then on.

My family had fled west and south from Duk Payuel on the night of the attack. They lived as internal refugees for a while in southern Sudan before returning to the village. A second djellaba attack drove them south again. When I called, my mother, sisters Agot and Akuot, brothers Goi and Aleer, two stepbrothers, and three stepsisters lived at the Ugandan border. My father had returned to Duk County, as soon as it was safe, with the youngest of his wives. He had added another wife since we last saw each other, and, as is the custom among the Dinka, made his home with the latest of his brides.

I began a phone and mail campaign to try to bring everyone in my family to Syracuse. It culminated with my filing family reunification papers with the Immigration and Naturalization Service early in 2002. The INS considered the case over the next few months and settled it with a compromise by helping some but not others. The immigration lawyers denied entry to my brothers and sisters, because they were self-supporting adults. However, the INS allowed my 14-year-old sister, Akuot, into the U.S. as a minor. My mother, Anon Duot, then won permission to resettle in order to take care of Akuot. Unfortunately, the line got drawn when I tried to bring my father to accompany my mother. He refused to enter the country without his new wife, which the INS told him would have violated American laws against polygamy. The bureaucracy that decided who got in and who stayed behind reminded me of the Dinka story of the hyena and the goats. The hyena desperately wanted to enter the goats’ hut so he could kill and eat. He bargained with God, saying, “Just let me inside. That’s the hard part. Going out will be easy.” For an immigrant, it’s harder to get into America than to leave the country after gaining entry.

Two years later, in February 2004—immigration red tape takes forever to clear up—my mother and sister landed at Syracuse Hancock International Airport. Syracuse’s newspaper and television stations had learned about the reunion and joined me at the end of a secure corridor to await the arrival. Christopher Quinn’s documentary cameras captured the reunion for his film. As my mother walked along the corridor, she looked at me and my roommates waiting to greet her. I could tell she struggled to pick me out, so I stepped forward. She threw her hands in the air and embraced me. We collapsed on the floor, rocking back and forth, as my mother chanted in Dinka.

“Yecue doc ben, yecue doc ben,” she sobbed. I translated for the reporters: My mother said her thanks to God.

That embrace lasted a full five minutes. I could have held her for hours.

She carried with her a cross and two Sudanese gupo baskets to give to First Presbyterian Church of Skaneateles as a way to thank its members for supporting me since my arrival. The gupos blazed in colorful designs of red, green, black, and white yard; Dinka use them to store valuables, collect the offering at church, or carry dry food such as groundnuts. The round baskets of my mother’s gupos were separate, but she conjoined the lids to symbolize the unity of the Sudanese and the American people. Those gupos now hang in the Skaneateles church.

Akuot, the sister John never knew, flies into his arms at the Syracuse airport in 2004, while their mother, just out of the picture, cries in jubilation.

I also had gifts. I carried two bouquets: roses for my mother, lollipops for my sister Akuot.

Akuot Deng Leek: When I got off the plane with my mother and walked through the airport at Syracuse, I strained to look for John. Several Dinka waited for us at the end of a walkway in the terminal. Which one was my brother? I figured it out when a man stepped ahead of the others and advanced toward us. He was very tall—the tallest in our family—and he was crying. He kind of crouched as he hugged us. I screamed and I cried in joy, and so did my mother. I think I might have said, “Is that you?” As I looked at him, though, I could see the family resemblance.

Reporters asked me how I felt. What a silly question. I felt everything. Great love for my family. Great relief at their safe arrival. Great concern for those they left behind. I knew many challenges lay ahead. My mother spoke no English. She would have to adjust to life in a city where only a few dozen people could communicate with her. My sister, whose English skills at least let her carry on simple conversations, would need to go to school, learn the customs of a new country, and make new friends. Both got a taste of culture shock when they stepped out of the heated terminal into a frosty winter day unlike anything they had seen in Africa, and then walked to a car that I told them I owned and drove. At least they would have my experience to guide them through the confusion, I thought. I had arranged for them to take an apartment in the same complex where I lived, so I could be nearby when they needed me.

I did not say so at the time, but I felt one more thing above all others. It was a private thing, so I did not share it. But I felt, very strongly, the grace of God. I can take no credit for it; grace is not something anyone can earn. Rather, grace opened before me like the door, and I walked through it. I knew I had been blessed. How else could anyone explain the impossible odds I had overcome—the dangers, the miles, the despair. God had not forgotten me after all.

MORE DOORS OPENED, AND MORE BLESSINGS CAME. I GOT INTO Syracuse University, and I found the woman I wanted to marry. It was as if God had chosen to make up for my years of torment by granting me many good things in a short span of time.

Martha Arual Akech and I lived in Pinyudu at the same time, but I don’t think we ever met. Martha had lost her parents when the djellabas attacked her village in the same year they shelled Duk Payuel. She made her way to Ethiopia with her three-year-old sister, Tabitha. Their survival placed them among the rare and lucky Lost Girls.

John embraces his American family—Akuot, Martha, and Anon, John and Akuot’s mother—at the home of friends Bill and Sabra Reichardt.

The first time I recall noticing Martha was in Kakuma. She made quite an impression on me. Some Lost Boys teased her and acted mean. She kept her composure and ignored them. It was a courageous performance. Not long after that, I saw her again at a Sunday night dance in her group area.

I approached her later, at her home in the Dinka manner, which is to say politely and slowly. I asked if I could talk to her, because I liked her. She was smart, practical, and strong in her Christian faith.

She turned me down. But in a good way. Something in the way she told me to leave made me think she acted out of Dinka custom, which forbade her to encourage a suitor in any way. She never gave me a specific reason she disliked me, so I thought I had a chance with her. I kept coming back to ask if I could be her boyfriend. She kept saying no, but she always let me come back the next day. This went on until finally she said yes, she would allow me to visit, and we could be boyfriend and girlfriend. That lasted a few months, until she left Kakuma in December 2000 to fly to Seattle with her sister.

I feared I would never see her again.

When I got to Syracuse, I asked around and got in touch with Martha, who was living in Seattle. We began talking and exchanging e-mails. In December 2002, after I learned my family had survived, I saw Martha again. We met at a reunion of Lost Boys held in Grand Rapids, Michigan, because so many had settled there. I flew from Syracuse on a ticket donated by the Skaneateles church. She stayed with one of her girlfriends in Michigan, while I stayed with my friends. We drove to a restaurant that first night, then spent as much time as we could just talking. In the mornings and afternoons, I met with the other Lost Boys in a big Lutheran church. We wanted to organize to speak politically with one voice on behalf of southern Sudan and to establish organizations to provide college scholarships for Lost Boys in the U.S. In the evenings, I met Martha in the home where she was staying. She had her friends and extended family with her, as did I. It was all very proper, according to Dinka tradition.

It was hard to think nothing but politics in the mornings and then try to ignore all debate and discussion to focus on Martha in the evenings, but I think I pulled it off. I tried to give my full attention to everything in its proper time.

About a thousand Lost Boys attended the gathering. It was fun to see people I had not seen since I lived in Kakuma, and to eat real Sudanese ayod, a maize-wheat porridge that the Lost Girls griddled to make flat, golden-brown cakes like Ethiopian bread. In three days of talks, we formed the Duk County Association in the U.S. as a continuation of a group we had created in Kakuma. We pledged to help Duk County rebuild from the devastation of civil war, making it attractive and worthy “not only for ourselves and those who follow us,” we said, “but also to honor all our beloved sisters, brothers, parents, relatives, and friends who we lost to the war.” The Lost Boys of Duk, together again after their dispersal, vowed to place health care and education at the top of their list of desired improvements.

We said we would work in harmony and integrity toward our goals. Little did we know how quickly political divisions would arise to challenge us. We should have guessed. We Dinka are headstrong and proud.

That was not my only disappointment at Grand Rapids. So many of the Lost Boys had adopted the clothing and hairstyles of American youths. They wore jeans that hung far too low, baseball caps, funny jewelry, and weird hairstyles. That just killed me. What would the elders have said if they had seen those boys? It is good for people to embrace their new country but not to such a degree that they forget their heritage. At least, it is not the Dinka way. It seemed ironic that so many Lost Boys could pledge their love of Duk County yet forget to honor their Duk ancestry through their clothes and manners. That was not respectful.

Martha stayed true to her roots, however. She worked hard as a nurse’s assistant at a Seattle nursing home and supported herself and her sister with her salary. She lived practically and dressed modestly. After our meeting in Grand Rapids, we began seeing each other regularly, each of us flying to the other’s city. To save money, we talked of living in the same town. The decision taxed us terribly. Which one of us should move? Martha had her sister Tabitha to think of, and by 2004 I had my mother, who spoke no English and knew nobody in Seattle. I convinced Martha that the move would be difficult for my mother, who could neither go with me to the West Coast nor live alone if I left her behind. Martha agreed to move East.

“You know what?” I told myself. “This is the girl. The one.”

I had promised the elders at Kakuma I would not go with an American girl. That was easy; I did not want one. Martha was a Dinka, she spoke the Dinka language, she knew the Dinka ways. And she was very pretty.

My parents helped with the marriage negotiations. My mother got my brothers to send for my father, and we talked on the phone.

“This is the girl I want to marry,” I told my father.

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s find out whether we are related and whether she comes from a good family.” He made inquiries in Africa. Her family came from the village of Abek, a few miles from Duk Payuel, so it was relatively easy to find people who knew Martha’s relatives. My father learned that her parents lived good lives. Nobody saw them die, so we hope to find them alive someday. Martha’s grandparents and brothers and sisters and cousins and aunts and uncles all passed muster. I waited for a year for my father’s investigations to be complete. At last, he said he could find nothing but good things about Martha, and he gave me his blessing.

Martha Arual Akech: I went to school in Kakuma. That’s where I learned a little bit of English. Not as much as the boys, though, because Sudanese women are so busy. They do a lot of chores—fetching water, fetching firewood, cooking, and so on. So we girls didn’t take the lessons as seriously as the boys. We learned some things, but we didn’t have a lot of time to practice them. I had almost no chance to read when I got home from school. Still, I learned enough English to help me later.

I finished primary school, passed the test for my certificate, and had begun the first year of high school when I was selected to come to America. I met John that year in Kakuma. Our schools were next to each other. When I left my house to go to school, I passed by his school. I had seen him around before that time, on the way to school or in the school kitchen where we both ate lunch. I remember him as one of the tall Sudanese guys. But there was no attraction then either way, from him or from me.

People passed by my house a lot on the way to school. They saw me in my compound as they walked to and fro. According to John, the first time he really paid close attention to me was when I was going to school and he walked behind me. He saw two boys being mean to me, but I was polite and did not talk back to them. He told me, later, that he watched me keep my cool, and he said to himself, “I like her.”

Boys often came and stood by the compound gates and waited for the girls to walk by. John came one morning, riding a bike, to my compound. One of the little neighbor girls came and told me, “There’s a man standing by the door.” I was inside the house, braiding a friend’s hair at the time. I looked through the window to see who it was. If it had been one of the guys I didn’t want to talk to, I would have sent the little girl back to tell him I wasn’t home. But I spoke to him, and he answered, “I just want to know when you will be free, as I want to talk to you.” I didn’t really have any idea if he was coming for me, or for somebody else. Some guys ask a girl about her sister or her friend before they approach that girl, and John may have wanted to talk about someone I knew. I told him to come back later.

When he came back, he told me he liked me and wanted to be my boyfriend. I told him, “I don’t like you,” but I did not give a specific reason. That meant I liked him. See, a Dinka girl would never say anything to a boy the first time they talked to indicate she liked him. What the girl wants to find out is if the guy really likes her. And if he does like the girl, he will come back the next day if she tells him to go away. The girl keeps sending him away, and he keeps coming back and coming back. That’s how she knows.

So I said, “No, I don’t like you. No, no way.”

So he said, “Why?”

I answered, “I do not know you very well.”

And he said, “That’s why I came, so you can get to know me.”

He probably knew I liked him. He kept coming back. Each time I told him to go away, he asked me to let him have one more day to talk to me. I don’t know how many times he came back like that, asking each time for one more day, before I said yes.

John and I were together for about six months before I had to leave. We did not go out on dates. There was nowhere in the camp to go, nowhere for a girl to date. And it was not accepted for a girl to be seen with a man outside her home, except at the dances on Sunday nights. Most of the young people went to the dances, where they might or might not see a boyfriend and girlfriend. If the boy or girl were there, they could dance together. That was the extent of our relation ship, other than walking and talking together.

One of the things that attracted me to him was the way he thinks. I had guys come to me before in Kakuma, but when I saw John, I compared him to those other guys and said, “This is a man.” If he has something to say, he says it. He gets his back up when he feels strongly about things. I liked that.

I also liked it that he always took responsibility, and he was very caring. A lot of boys had problems, and he would sit them down and help them solve their issues. I could see him doing good work from far away. And I never heard any thing bad about him at Kakuma. Camp is big, but if you did something wrong, it always got around. I knew who the bad guys and the good guys were at camp. John was one of the good guys.

I didn’t know if he was going to be accepted into America too. He came to say good-bye to me before I left, and he said, “Don’t forget me.”

I told him, “I can’t promise you I will wait for you. I don’t know what will happen here, or what will happen there. If things work out for you, that would be great.” John was kind of disappointed about that. He said he would think about me and wait to be with me, no matter how many years it would take.

I wanted a traditional Dinka marriage. That meant I had to give a dowry of cows to Martha’s family. We made the arrangements and agreed on the contract in October 2005. Martha’s uncles in Twic County, Sudan, and my father in the camp on the Uganda border concurred. At that moment, in the eyes of my people, we were married. If I had a mallet and a peg, I would have smacked the peg into the dirt outside my apartment to announce—whack!—that everyone endorsed the arrangements.

Like my father when he married, I lacked the wealth to seal the deal. I owned no cows, and my pay stayed only a few dollars an hour above minimum wage. I started saving money to send to Sudan, so that our proxies could buy and exchange cows in the Dinka manner. If I did not pay the dowry, I could not claim and name our children.

Martha, my wife, moved into my apartment. It was empty by the end of 2005, my roommates having moved on to independent lives. The adjustment to living with a woman confounded me at first. I had lived with men for nearly two decades. Out of sheer necessity I had learned to cook and to clean in Pinyudu and Kakuma, which married Dinka men never do in Sudan. I wanted to revert to our roles as man and woman, but sometimes my plans just didn’t work out. Martha came home one night from the hospital after a long shift and felt too tired to cook. So I cooked for myself as a married man. Hard to imagine for a Dinka, but I did it because I love her. I’ve done it again and again, as the need arises, and tell myself it is a compromise I must make as an American. I am not in Sudan, after all.

Our division of labor took on added importance when Martha became pregnant in 2006. She had taken a job as a phlebotomist, drawing blood for analysis and transfusion at St. Joseph’s Hospital, where I worked in security. We celebrated when our hospital co-workers tested Martha and announced she was expecting. The sonogram came back with a clear picture: We would have a daughter before the end of the year.

I arranged to build a house in Syracuse with the help of a city program that encourages low-income first-time homeowners to take out mortgages for homes within the city limits. At first, the program administrators wanted to deny my application, saying I earned too much money to qualify. They changed their minds when I showed that my income exceeded their limits only because I worked so much overtime at the hospital.

The whole family will live there—Martha, me, our daughter, my mother, and my sister. My mother and sister can help with the baby. I will leave the car with my family during the day and ride a bicycle to work. I had five bikes stolen at the apartment complex, where thieves cut the chains and rode away in the middle of the night. At my new house, I will lock the bike in a secure place.

As a Dinka, I must have a son to continue my name. That does not mean I love my daughter any less. Women have more of a sense of humanity than men. They are big-hearted, and they bring happiness wherever they go.

The prayer I say for my daughter, for my children, no doubt is the same as the prayer of many, many Americans. I want her to have a better life than I did. I pray for my daughter to be my “make up girl.” Through her, I will make up all that I lost. My parents took good care of me, but I left them and had to raise myself. I will not let my daughter grow up without my help. I will set up a bank account for her, with money going into it every week, so she will have the finest education and learn more than I know. I will make sure she learns to appreciate her family. I will see to it that she never suffers from want.

I know I will be strict with her, as my father was with me. That is the best way to raise a child. Teach the child at a young age to have discipline, to respect elders and family, and the rest of life’s lessons will take care of themselves. This will give my daughter the best of two worlds: The gifts of Dinka culture, in a land where those gifts will take her as far as she wants to go.

The duty of naming the baby belongs to my mother, as representative of the women on the husband’s side of the new family. By tradition, the name Agot has been set aside for my daughter. It is always the name of the oldest girl in my family; I have eight aunts named Agot. My second daughter will be Akur, also because of family custom. The first son born to Martha and me will be Leek and the second Aleer. That’s the system. My contribution to my daughter’s christening will be what Americans call the “middle name,” which is actually another family name among the Dinka. I want her to be Agot Dhieu-Deng Leek. That way, my father’s name will live on in America.

To take some of the financial pressure off my growing family, I secured a Pell Grant, a federal financial award for undergraduate education that does not need to be repaid. I’ve also secured additional aid to attend Syracuse University through a New York State program that helps pay the tuition of first-time, low-income students. I thought about a major and settled on public relations. An advisor interviewed me about appropriate classes for my first semester and quickly determined that I had chosen wrongly. Instead of public relations, I wanted a public policy major in the public affairs program. The advisor, Joey Tse, told me public affairs deals with government policies, while public relations focuses on communicating ideas. Every government policy that affects people naturally has to be communicated, so in reality the two are not completely separate. But the advisor essentially was right. I want to make a basic difference in the lives of refugees and immigrants. I want to make changes in policy that will make lives better.

Joey Tse told me to take a class from Bill Coplin, a professor in the Maxwell School who teaches public policy. On the first day of class, Professor Coplin demonstrated the importance of such policy on a basic level by cutting up a student’s fake ID card. He asked for comments, and I raised my hand. Almost alone among the students in class that day, I told him that if we don’t like the law, we may work to change it, but until then we must obey it. He took an interest in me and spoke to me after class. From then on, he worked with me not only to master the basics of my various classes but also to assemble the skills I would need as an American university student. He told me I had to learn to type, then set up a series of typing lessons. He showed me how to use a computer to set up spreadsheets and plan PowerPoint presentations. And he arranged for tutors to help me with my speaking and writing. It was more than any student should have a right to expect from a professor, yet it was exactly what I needed to have the confidence to express myself. I know these skills will help me influence people on behalf of international refugees.

My dream is to get a job with the United Nations and work in Africa or America. If I have the time and money, I would like to study immigration law. Refugees in Africa would best be served by someone who knows the ins and outs of international law, yet who understands the depths of their troubles firsthand. Oppressors hurt people because of their religion or their politics or their ethnic or racial background. Too many victims lack someone to speak for them on the world stage. The peoples of southern Sudan, for example, are still scattered in Uganda, Ethiopia, Chad, Congo, the Central African Republic, Kenya, and other countries. Ending the diaspora requires people with a variety of skills and the motivation to use them. One thing Professor Coplin’s class taught me was to look for the people in power and watch how they exercise it. On the ground in faraway refugee camps, the people with power are immigration agents and lawyers. I need to change the laws so they will let more refugees out of their misery. That is my mission.

I DECIDED TO DO WHAT I COULD TO CHANGE LIVES IN A CONCRETE way. When I arrived in Syracuse, the Lost Boys hadn’t organized themselves. We needed a forum, I thought, a foundation, to channel our energy. With the help of others interested in such an organization, I set up the Sudanese Lost Boys Foundation of New York. Our members include about 150 Lost Boys in Syracuse, about 45 in Rochester, and a few more in Utica and other towns. We set up the foundation to accept and disburse charitable donations. My intent was to create a funnel for money to help the Lost Boys pay for college tuition, books, computers, and other things they needed to succeed in America. The foundation office also served as a place for Lost Boys to relax and discuss issues affecting them. We raised $35,000 in the first year.

The most amazing donation came from the philanthropic Rosamond Gifford Foundation of Syracuse. When I talked to other foundations, they said no, no, no to my requests for donations. The breakthrough occurred when I approached Kathy Goldfarb-Findling at the Gifford. I found her office on the Internet when I Googled the words “foundation” and “Syracuse.” I called her and said, “My name is John Dau, of the Sudanese Lost Boys Foundation of New York.” She said, “Okay, what do you need?” I told her the foundation I represented did good work helping Lost Boys go to school in the U.S. but that we needed money. She told me to visit her in her office downtown the next day. As I made a note of that, I asked her again what her name was. “Kathy with a ‘K,’” she said. I remembered that and have called her that ever since.

The next day, I put on my dark suit—it is so hard to find clothes to fit a skinny man who stands six feet eight—and went to her office with some of my friends. Kathy-with-a-K took us to another room and made us feel welcome. She invited me to say why I had come. I don’t remember what I said, but I didn’t say much before Kathy excused herself, got up, and left the meeting. When she returned, she held out a check. We were stunned. She gave us $5,000 on the spot.

Kathy Goldfarb-Findling: There were two things that struck me immediately about John. The first was that he was so clearly trying to create structure and organization within the community of Lost Boys, and he was working very hard at finding a focus for them. That was the first thing I found to be a bit extraordinary. Then, he was in a leadership role, he was comfortable in that role, and he was trying to accomplish something that to me, appeared to be really difficult to do: To organize these young men around the idea of creating a scholarship fund to further their education. Given that they were all in relatively low-paying jobs and sending a good deal of money back to the refugee camps where they had come from, and where a good deal of their families still resided, it seemed to me that he had taken on a difficult task.

That gave us the momentum we needed. She recruited others to support our foundation and even organized a fund-raiser during the showing of a PBS documentary about the Lost Boys on Syracuse television. Kathy’s foundation paid for four brand-new computers in our office and even picked up the expenses when eight other Lost Boys and I traveled to a national reunion in Phoenix, Arizona. Many Sudanese, including some still in Africa, have benefited from Kathy’s generosity. I cannot thank her enough. In America, nobody seemed willing to take the Lost Boys Foundation seriously until the Gifford Foundation stepped up and made its support very public.

After a year as president of the foundation, I stepped down to give others a chance to serve. That was at the end of 2004. By that time, I had plans to raise money for other projects. One involved creating the Sudanese Association of Central New York, an umbrella organization that includes women, families, children, and others who can’t technically be called Lost Boys. Another involved bringing American-style medical care to Sudan. I didn’t want to announce the health care project while raising money for scholarships, because I thought they would detract from one another. However, after I left my office as foundation president, I felt free to act.

I spoke to “Grandfather” Jack Howard and told him I wanted to build a medical clinic in Duk County. Grandfather Jack didn’t bat an eye, although he later told me the idea moved him profoundly. He said it would take a lot of work, but it could be done. I chatted with relatives in Sudan and Uganda too, and they said the villagers of Duk County supported the idea wholeheartedly.

Penny Allyn, who had helped me when I moved into my apartment and went with me on my first trip to the grocery store, was married to Bill Allyn, whose family co-owned Welch Allyn, a huge company that makes medical diagnostic equipment. With Grandfather’s help, I wrote and polished a proposal to create a foundation to build a clinic in my homeland. Although the Welch Allyn company could not make a corporate donation because of rules limiting its charity to local causes, members of the family gave as individuals. In just a few weeks, Grandfather and I got pledges from the Allyn family totaling about $40,000. We figured that represented about a third of what we needed.

After that, Grandfather and I launched the project publicly. With the endorsement of other Lost Boys from around the United States, we created a nongovernmental organization to operate efficiently overseas. We obtained the proper Internal Revenue Service status, so donors could claim contributions as deductions on their income taxes. We called our project the American Care for Sudan Foundation. Our minister at First Presbyterian Church of Skaneateles announced it to the congregation, and the members promptly gave us an additional quarter of what we needed. Volunteers came forward to help push the project. We established a board for the clinic and staffed it with a lawyer, a doctor, a contractor, a Welch Allyn company officer, and others whose practical experience would help the clinic become a reality.

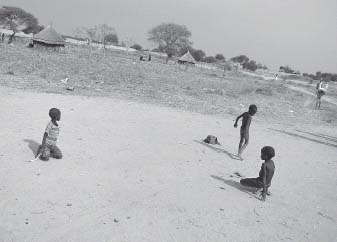

Boys play a traditional Dinka game in the dirt of Duk Payuel, John’s Sudanese village, where he plans to build a clinic.

Our best advice came from a nonprofit, missionary group out of Arkansas that had done work in Africa. The group, Tech Serve International, told us to buy everything we needed in the United States and ship it to Sudan. That way, we would get the best deals on materials, yet still pay local laborers to assemble the clinic building. Most assembly would have to take place after dark, we learned, as the slightest touch against the bare metal framing would cause severe burns under the blazing sun and 120F midday temperatures.

The plan calls for first clearing the ground with teams of oxen and compacting the dirt with logs to prepare it for construction. Local laborers will do that work for $1.25 an hour—a pittance by American standards but a good wage in southern Sudan. A thatched fence about the size and shape of the outer edge of a football field will surround the compound. Inside, workers will erect a simple, steel-frame building, 92 feet by 38 feet. More than a dozen rooms will include proper spaces for childbirth and recovery, which are crucial in a region noted for high infant mortality. There will also be four examination rooms and a sterile room for sewing wounds and setting broken bones. Supplies to keep the clinic running will initially be funneled through the foundation, but the people of southern Sudan likely will press the government to pick up any slack. Already, high-ranking officials of the new Sudanese government, including the head of intelligence, have endorsed the clinic. A Sudanese doctor in Canada has volunteered to staff the building when it opens, and Dinka nurses are ready to go to work, too. Services will be free to the patients.

Our initial budget totaled $115,000. That’s a lot of expensive equipment to place on the ground to await assembly. Grandfather asked me if I had any fears that the Dinka would steal anything left unsecured. I told him that if they did, they would be dead men; the natives would defend their clinic with their lives. Besides, I hope they do not have long to wait. I expect construction to begin when the ground dries in 2007. Perhaps by June it will be ready for its first patient. I hope so. For 50 years now the Khartoum government has pledged advanced medical care to the dark-skinned tribes of southern Sudan without delivering on the promise. For five years, an international relief organization has been trying to open a healthcare building in the southern Sudanese town of Poktap, all the while promising swift completion to the village elders. When my pastor at First Presbyterian, Rev. Craig Lindsey, went to Sudan to look for possible clinic sites, one of the elders told the organizers of the project, “If you fulfill this promise, you shall have a full and blessed life. If you lie to us and do not fulfill your promises, as others have done, may you and all whom you care about die a painful and long death!” And he meant it, I’m sure.

“Grandfather” Jack Howard: I have a great relationship with John. I have been a mentor to him for several years. He calls me nearly every day, to ask for advice about taking classes, or moving in with Martha. It makes me feel good that I can be an important part of his life. The amazing thing about him is that he is so intuitive. It came out of the blue sky that he wanted to build a clinic, and he did it. The credit for the clinic goes to John and the Lost Boys. It just never would have happened without John Dau.

I expect the clinic to have an immediate impact. More than 19,000 residents of Duk County who fled to other parts of Sudan during the civil war will probably return once the nation has a secure peace. The county’s elders fear that the influx of returnees will place a heavy burden on the food producers, and the sudden introduction of so many people likely will spread chicken pox and other communicable diseases. But sufferers of many other diseases—including malaria, guinea worm, and kalazar, a deadly disease also known as black fever that spreads through contact with the sand fly—will find relief for the first time in memory at our clinic.

The Dinka deserve the wonders of modern medicine. When I lived in Duk County, young children suffered from a disease called taach. It’s a kind of chronic fever, and the symptoms last for two months. The victim’s father typically applied a homemade Dinka remedy. He put a piece of metal in fire until it glowed red-hot. Then he placed it against the victim’s skin on the neck, back, or knee. The skin smoked and melted, and the burn left a nasty red welt. Some said it made the pain of taach go away. I always suspected it merely took the patient’s mind off the existing pain and substituted another that felt even worse. If I can open this clinic, maybe the babies born in Duk County will never be burned again.

As southern Sudan has moved toward a new era of freedom, Duk County hasn’t had a single medical dispensary to meet the challenge; residents of my hometown still have to walk 75 miles to another village if they wish to receive modern health care. Thanks to the many Lost Boys who talked with the foundation directors and helped plan the clinic, the building has been designed to meet the needs of the Dinka and to be built as efficiently as possible. The best way for Americans to help Africans, I believe, is to get Africans in the United States to oversee any philanthropic redevelopment. African immigrants had to fend for themselves to succeed in America, so they know how to get things done and how to get the most from a dollar. But having also lived in their home countries, they know who has to be bribed and who can be ignored, as well as how to appeal to the values of the indigenous people. I call this concept “Africans for Africa.” The same thing would work in other regions—Southeast Asians for Southeast Asia, Indians for India, etc. It certainly works better than throwing money at an inept and corrupt government and hoping some of it spills into the right pockets.

Fund-raising efforts for the clinic coincided with the completion of God Grew Tired of Us, Christopher Quinn’s documentary. After he put the finishing touches on the film, I got a lot of financial help in unexpected places. Liz Marks and her twin daughters, Lily and Isabel, teenage students at the Dalton School in New York City, saw Christopher’s documentary. They asked me to speak at the school, and I did. Lily and Isabel asked people to donate to the Duk County clinic, and they raised about $14,000. I was very impressed with the determination and smarts of these two girls. Liz also raised money to help pay my way to Sudan at the beginning of 2006, so I could inspect the ground for the clinic and reestablish family ties. Christopher’s girlfriend, Victoria Cuthert, also gave me a sizable donation toward my trip.

I had spoken to my father before the trip, and he suggested we build the clinic on a piece of land that his family had farmed since God made the world. He had a specific place in mind. It had good water, even in drought years, but we had not grown maize or sorghum on it for a while.

I wanted to walk all over the spot and talk to the elders to make sure there would be no problems. And, to be frank, I wanted to see my boyhood home again.

I had only 20 days off from the hospital to see my family and homeland before returning to Syracuse. Given that I had not seen my brothers, sisters, and father in 19 years, it did not seem long enough.

I booked a plane from Syracuse to Kampala, Uganda. My brothers met me at the airport. I recognized them from the pictures they sent me; they looked quite different from the way I remembered them. I am sure I looked different, too. My brothers slaughtered three goats to welcome me back. They invited relatives and neighbors to a big outdoor feast.

After five days with my brothers, we rented two cars and drove to Juba, where I chartered a small, propeller-driven plane to take us home. The flight lasted an hour. It might seem extravagant to hire a plane for such a short journey. I had no choice. Land mines dotted the roads heading north out of Uganda.

When the plane landed in Poktap, we picked up another rental car and drove to the village where my father had resettled. As we approached, I saw things I had not seen since I was a boy. Long-horned, long-eared cows, white and tan. Boys carrying milk in gourds. Boys in cattle camp. Faces with Dinka scars on the foreheads. As we drove through the village, we heard voices saying, “The children of Deng Ayuel are here!” They trilled a joyful Dinka chant, Yeyeyeyea-ah! One of them ran very fast to tell my father.

He had gone to the landing strip, expecting us to arrive there. Instead, we had driven over the dusty, red-dirt roads to his home. I met his youngest wife before I saw him. My brothers and I were all very thirsty, as our car had broken down three times on the road, and we had nothing to drink while we waited out the repairs. I asked for water, but my father’s new wife said that out of respect, we could not drink anything until he returned. We waited 25 minutes, scanning the horizon, before we saw him coming on foot with his neighbors and the village elders.

He was still a respected judge, still a big man in the village. Figuratively, I mean. I could not believe how short he looked. Of course, I was looking down on him at the time, instead of up at him as I had as a child. I noticed that the scars on his forehead that distinguished him as a Dinka had faded with time.

We cried together, and he put his arms around me. He still had the wrestler’s strength in his arms. He gripped me and my brothers in a big circle and gave a prayer, right there in front of his house.

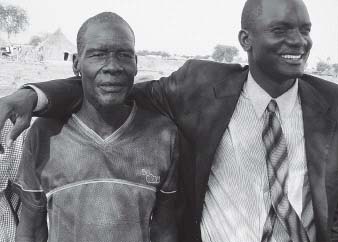

All smiles, John hugs his father, Deng Leek, at their reunion at Poktap, Sudan, in 2006.

“He was lost to me, oh, Lord,” my father said, “but now he is alive. And I thank you for that, Lord.” It reminded me of the welcome given by the father of the prodigal son in the Gospel of Luke.

I stayed with him for five days. He slaughtered five goats and one cow for the village to celebrate. I opened a case of wine I bought in Uganda, so the celebrators could drink. It was the only time I ever bought wine.

My father kept touching me during the length of my visit, as if to reassure himself he had not imagined my existence. He seemed proud.

“This is the first child who brought America to our country,” he said. “This is he first child who really told of our problems to the American people. And now he brings us a hospital.” There is no Dinka word for “clinic,” so I did not try to correct him. I showed him some pictures of First Presbyterian Church of Skaneateles, and I took pictures of southern Sudan to share when I returned.

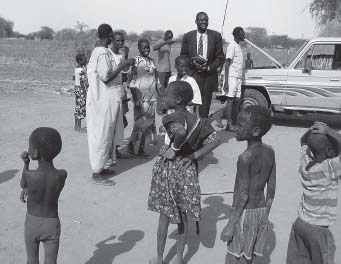

Dinka children and their families in Duk County wonder what to make of the well-dressed American. John’s car, its hood open, broke down often.

We drove the 18 miles from my father’s village to Duk Payuel to inspect the site my father had selected. I got out of the car and sat on the ground at the edge of a stand of grass that stood eight feet tall. This feels like my country, I thought, even though I have not seen it for so long. I visited the huts where my family slept on the night of the attack, walking around and reliving the events in memory as if watching them on a movie screen. I bent over and scooped up the dirt, running the grains of dust through my fingers. I visited the place where my mother buried my placenta after I was born. The Dinka never throw the placenta away. Instead, they hang it in a gourd outside the door where a baby has been born. Later, the family buries it to make a spiritual connection between the child and the place of birth. I stood where my placenta had been placed in the ground and felt my spirit reaching down, like roots of a thirsty tree seeking water.

I tossed stones into branches to dislodge the palm fruits I had eaten while tending cattle. I found the ancient beehive, still active, where I gathered honey as a boy. Best of all, I found my tree, a tall kuel, with one long, curved branch that brushed the ground. As a child, I used to cut its bark, collect the sap that ran out, and chew the congealed gum. I also rocked on the long, low branch with my friends. In 2006 I sat again on the same limb and said, to nobody in particular, “Swing me!”

It was so good to be home. Too bad it could not last. My time grew short, and I had to return to the United States. Unfortunately, I had booked no return to Uganda. No planes had arrived at the Poktap landing strip on which we could make a return flight. My uncle, the governor of Jonglei state, said he would have liked to help my brothers and me, but he had no planes to put at our disposal.

“Lord,” my father prayed aloud, “find a way to send my sons back home.”

Very soon, within an hour, a plane landed. I negotiated with the pilot, and he agreed to fly us to Lokichokio, on the Kenya border, for a thousand dollars. It was our only option for transportation, so I willingly paid it. We hugged my father and boarded the plane. Sudan dissolved beneath me as the plane headed into the sky.

From left, John Dau, Panther Bior, Daniel Pach, and filmmaker Christopher Quinn pose for a portrait at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival.

After an uneventful flight, we rented a car at Lokichokio and drove to Uganda. Along the way, we drove through Kakuma town. My friends still in the refugee camp heard I would be passing, so they tried to meet our car. We did not know of the planned reunion, and in our haste to catch a plane we did not stop. I later heard they slaughtered two goats, which they ate without me.

I SAID MY GOOD-BYES TO MY BROTHERS AND FLEW TO SYRACUSE on January 18. Four days later, I was on a plane again, this time for the world premiere of God Grew Tired of Us at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. I had never heard of Sundance, but Christopher said it was an important event, and he really wanted me to attend. I got off work again and flew to central Utah in the middle of winter.

As I stepped off the plane, I looked east toward a towering chain of snow-covered mountains. Although I had not been in icy mountains before, they were not the strangest part of the journey. Almost as soon as I emerged from the secure corridors of the airport into the public reception area next to the baggage claim, I stepped into the most topsy-turvy world I had ever seen.

Hollywood.

CNN wanted to interview me. So did NBC’s Access Hollywood. A buzz had been building in Salt Lake City, the biggest population center near Park City, about Christopher’s movie. People thrust cameras at my face and turned on bright lights. Then they fired questions at me. I answered them as politely as I could, but I felt like an animal in a cage. Fortunately, there were many Lost Boys at Sundance to take some of the interviews. About 140 of the boys who were living in Utah watched a special screening. Afterward, one of the them, a University of Utah honors student named James Alic Garang, told the Salt Lake Tribune, “A film like this will get the word out to the American people, who might not know about the Lost Boys—or even where Sudan is. The world has been turning a deaf ear to Sudan for a long time.” I agreed. While being the subject of attention might seem fun, it meant nothing compared with the good the publicity had done for Sudan.

After the initial screenings, the pace of the interviews and the requests for introductions increased. I met many people Christopher said were celebrities. A nice man, very sincere, shook my hand, and spoke to me. He said his name was Brad Pitt. I had not heard of him, so I asked him what he did. He said he worked as the executive producer of Christopher’s documentary. Sometime later, somebody told me Brad also acted in movies.

I attended all of the showings of God Grew Tired of Us. As the lights came up at the end of the film, Christopher introduced me and the other two Lost Boys featured in the movie, Panther Bior and Daniel Pach, and asked us to take questions.

“How is it in Africa now, John?” somebody asked me from the audience.

“Oh, I just got back four days ago from Sudan,” I said. “I am building a clinic in my homeland. It is going very well.”

A woman came up to me after the talk and said, “John, I want to help your clinic. Whom should I write a check to?” I gave her the name of the American Care for Sudan Foundation, and she filled out the check on the spot. Then, she tore it from the checkbook, handed it to me, and disappeared into the crowd. I glanced at the check. Twenty-five dollars. Nice. Then I looked more closely.

I had missed the zeroes. It was $25,000.

I showed the check to Christopher. “Oh, my,” he said.

I wanted to thank the woman who gave me the money, but she apparently wanted to remain anonymous. I did not see her again at Sundance. I later learned her name and that she came from Texas.

The foundation got another check, for $5,000, from another Texan, and I got to take a half day off. A viewer who liked the movie paid to have Daniel, Panther, and me go tubing down the mountains at Park City. We sprawled in inner tubes and skimmed across the snow on a very cold day. Needless to say, I had never done anything like that in Sudan.

At the end of the festival, the film won the Grand Jury Prize and the Audience Award, the fourth documentary in Sundance’s 25-year history to take the top awards from both critics and public. The attention can do nothing but good for southern Sudan. Americans will realize how badly my homeland has been hurt by the war, and how the skilled people necessary for its redevelopment have been scattered to the winds. With America’s help, sparked in part by Christopher’s film, the Dinka will replant, rebuild, and reestablish democracy. Because of the film, I have already seen doors open to me that never would have opened otherwise. I spoke to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan’s personal secretary about my Africans for Africa concept in early 2006.

I am sorry that John Garang will not help lead southern Sudan into a new age, because I appreciate what he did in his 22-year fight against the Khartoum government. In July 2005, three days after he took the oath as vice president in Sudan’s transitional government, he died in a helicopter when he was returning from talks with the Ugandan president. Some southerners suspected foul play, but the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, which he helped negotiate and which led to the Government of National Unity, gives southern Sudan the best prospects for lasting peace in more than a century. The agreement will bring half of the nation’s oil revenue to the south, and that money will strengthen the towns and tribes, as well as the SPLA units that surround and support them. I frankly do not know how Garang managed to get the Khartoum government to agree to share revenue. Even more astonishingly, he won autonomy for the southern regions, to be followed in 2011 by a referendum on independence. Ten states in the south, including Duk County’s state of Jonglei, will vote on whether to stay with Khartoum or break away. Southerners favor independence by huge margins in every straw poll, so I expect the ten states to become a new country. Maybe they will call it Kush, to cement the nation’s identity to its biblical foundations.

I hope to return to Sudan in 2010 and 2011 to campaign for independence and to be there when the people of Kush achieve it. This is my generation’s duty. We have to see independence through to its realization. Previous generations failed, and that is why southern Sudan suffered for so many years.

Much could still go wrong. The Khartoum government has proved itself adept at playing one dark-skinned tribe against another, primarily Nuer against Dinka, to destabilize the south. It is quite possible that the djellabas will renege on their president’s promise to let the south go free and take its oil reserves with it. We must not let that happen. The front lines in America’s current war run through many countries where religious ideologies clash. Keeping southern Sudan strong will pay dividends in the war on terrorism and create an American ally in a strategically contested part of the world.

It will be tough getting all of the Lost Boys to agree on a political course of action. We tried to do that at the Phoenix convention and found our attempts to elect a leader and set an agenda regretfully splitting along tribal lines—Dinka against Nuer, Bor against Bahr el-Ghazal, and so on. I am confident, though, that the people of southern Sudan will focus on their common desires and dreams as they shape the future of my ancestral homeland. If we keep our eyes on the prize of independence, we will ignore the distractions and temptations certain to be placed in our way by the Khartoum government.

Finding unity in a shared vision is my prayer for my new homeland.

Celina Martinez, graduate student at Syracuse and John’s writing tutor: I told John once, “Language is power.” He was silent for a second, and said, “Language is the reason we have fighting among the tribes in Africa.” He says these amazing things. Another time I told him that, considering his life story, he was really lucky. He said, “I don’t feel lucky.”

America has many tribes. Irish, German, Mexican, Greek, Chinese, Italian, and on and on through scores of other ethnicities, religions, and languages. Jews and Christians and Muslims. Great-grandchildren of slaves and great-grandchildren of slaveholders. Those who crossed the ocean in first-class cabins on luxury liners and those who traveled in steerage. Red-state citizens and blue-state citizens. Unlike the Dinka, whom God placed along the Nile long, long ago, Americans live in a young and restless country. Everyone is an immigrant in this nation of immigrants; even the so-called “Native” Americans once traveled to this continent from Asia. As an outsider to the U.S., who knew next to nothing about America before arriving on these shores in 2001, I have observed many things that others have stared at but failed to see. Too many Americans have put on blinders. They see only what they choose to, not taking the time or effort to try to understand the big picture. I believe a macroscopic view of America must take account of all things that make this country great, as well as the things that stand in the way of its achieving even more greatness.

When I talk to my American friends about this country, the conversation reminds me in some ways of the parable of the blind men and the elephant. In the story, a group of men who have been blind all their lives encounter an elephant on the road. They have never come across one before, so they place their hands on the beast to try to understand it. One man places his hands on the animal’s great, gray flank and announces, “It is just like a wall.” Another feels the elephant’s long ivory tusk and declares, “It is just like a spear.” A third grabs the trunk and says, “It is just like a snake.” And so it goes, with each man exploring a different part and none able to articulate the true nature of the beast. Everything in America presented itself as new to me; I have seen with fresh eyes the head and heart and belly of the beast.

I believe a young woman in my class at Syracuse University mainly saw the elephant’s blundering feet and not its great heart. I had given a talk about perseverance in Professor Coplin’s class, and I told stories of my life in Africa and America. Lisa rushed up to talk to me afterward. She wanted to know whether Africans felt America had done enough to help them. Lisa accused the United States of neglecting some big problems, and she said some very critical things about my new country. I told her to sit down. I explained to her how so many people, some of whom I had never met, gave me warm clothes, bought me groceries, set me up in my apartment, and helped me go to school. I told of how my new country encouraged me to succeed by giving me access to grants and loans to further my education.

Is this enough? I told Lisa it was enough for me and for anyone else helped by such generosity. The Lost Boys had never known such gifts, and they could never have expected them in the closed societies of Africa. In America, many treasures get taken for granted, because people see them every day. As an African who grew up with so very little, I told Lisa I thought America had done right by me, and I blessed my new country. I looked in her eyes and saw that she was thinking, maybe about things she hadn’t considered before. After that, she asked me to meet some of her friends and speak at their meetings. Now we enjoy talking often, and she has made plans to put on a concert to raise money for the clinic.

Without even pausing to think, I can tell you America’s greatest strength is its enormous spirit, manifest in its generosity. Americans deserve huge credit for giving to those in need. They open their checkbooks and make donations to people in Africa, in Asia, in Latin America, and in devastated New Orleans, and they seldom know personally who benefits from their altruism. Nowhere else in the world do people give so much, so freely, with no expectations in return. Look what happened when I got my first job and needed someone to give me a ride. I called a friend, Jim Hockenbery from Living Word Church, in the middle of the night and asked him to help. Now that I understand how my requests violated American customs, I feel embarrassed for my actions all those years ago. Yet at the same time, I feel a great love for all who sacrificed sleep or time with family to help me out, no questions asked. You tell an American you need assistance, and chances are you will find in his or her response the spirit that made this country grow and prosper.

I look at Jack Howard, my new grandfather, and I see a man determined to do all he can to help others succeed. An elder by any standard, in his 80s, he has the energy of a teenager and refuses to give up on any task. When the Lost Boys came to central New York, he treated them like his grandchildren. Jack has done so many things for me, from showing me the value of each American coin, to introducing me to candy bars and asking me if I liked them, to pushing the Duk County clinic toward its grand and glorious opening day. All the while, he has encouraged me to do what I could on my own. This is so good, to urge others to succeed, while being there to help when needed. He has a clean heart. I want God to give Jack Howard years more to live, so he may continue to go good things.

Then there is Professor Bill Coplin at Syracuse University. He taught me many things that had nothing to do with public policy, because he knows education extends far beyond the walls of a classroom. He helped me to prosper and to remember to take care of myself as I try to take care of the Lost Boys and the people of Duk County. “Before you can feed others, you must first feed yourself,” Bill told me.

Professor Bill Coplin: The first time I called on John in class and heard his accent, I thought he might be Nigerian, maybe a highly trained student whose parents worked in the diplomatic corps. He is a mature, thoughtful student, but he likes to argue. He’s stubborn, too. That probably helped him survive when he was in Africa. He has a huge capacity for hard work, and he takes a tremendous amount of responsibility. He kicks himself, and that’s crucial to success. The fact that he survived impresses me. Even more, I am impressed by his being such a nice person, despite everything that happened to him. Maybe his challenges made him what he is, but I think he was special to begin with.

America is full of people like Jack and Bill. People like them have made America a welcoming place to immigrants for generations. Nobody can cause me to fail in America; nobody stands in the way, as they do in traditional African societies, where privilege, wealth, and membership in the insiders’ group count for more than integrity and hard work. The United States has no group actively working for others to fail; rather, it is populated by many who seek to promote goodness.

In what I’ve seen of America and Americans, race and social class do not seem to define the individual; even physical handicaps are not relevant. My successes and my failures are my own, and I like living my life that way. True, I had people like Jack Howard and Susan Meyer and Bill Coplin to help me, but I know that millions of Americans like them are waiting to help others who take the trouble to help themselves. There is no other country in the world like that.

America’s greatest weakness, I believe, lies in how it has drifted far from the love of family, at least as the Dinka understand that love. Among my people, a child can never know the world on its own, or even through the eyes of just a mother and father. Young parents cannot impart all of the wisdom necessary to raise a child. They are off cultivating crops, building huts, cooking—the hundreds of tasks required to keep food on the table and a roof overhead. Therefore, aunts, uncles, and grandparents help instruct a child about Dinka values. Even nonrelatives of a certain age are treated as family members, assuming the right to correct a wayward child; if strangers saw a Dinka boy or girl misbehaving, they would admonish the child and receive the parents’ thanks for doing so.

Special honors and respect go to all who have gray hair, especially grandmothers. They watch the little children all the time, teaching them how to speak, how to act, how to be good Dinka. When my grandmother in Duk Payuel saw me acting up, she would say, “Stop that! You will destroy the family name!” And then she would tell me what to do to bring honor to the family. Like children everywhere, I grumbled from time to time, but like every Dinka, I learned never to say a disrespectful word to her or any other elders. My mother will live with me in my house until she dies. She will teach the Dinka tongue to my baby, making it her first language. Grandmother will help raise my children to be good Dinka, while I will raise them to be good Americans.

Here in Syracuse, among my neighbors, fellow students, and co-workers, grandparents generally do not live in the same home as the children. Young families claim they want to live alone to assert their independence—but at what a cost! They lose the advice and support of grandparents, and they are not there to return the care their grandparents are due. I think with despair about old people getting sick alone or falling and breaking their bones (I witness their agony at the hospital), and I see how the pain of their bodies gets compounded with the anguish of loneliness.

I think America has lost much of the benefits of the tribe by putting its elderly in rest homes. And by clustering children in day-care centers—so many young calves mooing together in one pen! By separating the generations of a family, the circle of life gets broken.