“A chilled plastic bottle of water in the convenience store cooler is the perfect symbol of this moment in American commerce and culture. It acknowledges our demand for instant gratification … and our token concern for health. Its packaging and its transport depend entirely on cheap fossil fuel.”

—Charles Fishman, journalist, Fast Company, 2007

YOUR LEAN AND GREEN PRESCRIPTION

zero-calorie beverages (Eat your calories, don’t drink them.)

ENJOY DAILY

Unlimited filtered or purified tap water

Fresh brewed coffee or tea (especially green, black, or herbal)

IF YOU CAN AFFORD THE CALORIES

Up to 6 ounces 100 percent fruit or vegetable juice

Up to one (5-ounce) glass of wine a day for women, up to two glasses for men

LIMIT

Sports drinks (unless you are an athlete exercising more than 60 minutes a day and not looking to lose weight)

Designer coffee drinks on the go

Yogurt drinks and commercially made smoothies (unless you can afford the extra calories and the ingredient list is clean)

AVOID

Bottled water

Canned or bottled sodas (even diet), juice blends, diet drinks, health waters, and all of the hundreds of “hybrid” drinks on the market

Any juice drink that isn’t 100 percent juice

Any drinks with artificial sweeteners

Energy drinks

Milkshakes

Single-serving or highly packaged beverages

Beer and spirits

For many people, the biggest obstacle to weight loss may be sitting in their glass rather than on their plate. Are you nursing a cup of something or other all day? Texting your barista? Deciding that 4:00 is the “new” 5:00 when it comes to pouring an acceptable glass of wine?

If so, then listen up. According to the 2004 scientific report that was the basis of the 2005 US Dietary Guidelines, “Available prospective studies suggest a positive association between the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain. A reduced intake of added sugars (especially sugar-sweetened beverages) may be helpful in achieving recommended intakes of nutrients and in weight control.”1

If that’s too techie for you, consider how one of my sassier clients put it: “The size of your glass determines the size of your ass.”

Here’s the skinny on getting lean: Liquid calories have to go. Or at least go down. A lot. How easy, because it’s one of the clearest and most precise overlaps with a greener diet as well.

The research is clear. Liquid calories do not register in your brain the same way that food calories do, which means your body doesn’t recognize them and adjust your intake accordingly. People who drink a lot of liquid calories tend to weigh more than people who don’t.2 Think you’re okay with diet drinks? Think again. Drinking diet soda has not been shown to help you lose weight; it may even contribute to weight gain.3

Perhaps more alarming is that our children are learning that tap water is something to be shunned, that designer coffee concoctions resembling caffeinated milkshakes are an acceptable (if expensive) late afternoon “pick-me-up,” and that there is no health downside to slurping on a sea of liquid calories all day long. And as you’ll soon see, the packaging coming from all these beverages is staggering. It’s the perfect storm for your hips, and it’s adding tons of carbon to your personal plume.

Water

If things such as fish are murky, thank goodness beverages are crystal clear. Drink cleanly. Skip the beverage aisle, and you’ll start trimming immediately. Stick to nature’s best—purified water.

LEAN BENEFITS LEAN BENEFITS

I’m sure the lean benefits of water are rather obvious, but here’s a quick review: Drinking water helps keep your skin looking great, your GI tract healthy and regular, your energy levels and focus maximized, your munchies at bay, your workouts going strong, and toxins flushed from your system, plus a host of other benefits. It’s made by nature, and it’s a renewable resource. Plus, it’s zero calories, so there’s no weight gain, which is especially important because liquid calories don’t register with your brain. As for other beverages, if you can afford the extra calories, small amounts of 100 percent fruit or vegetables juice and wine can provide numerous health benefits, too. I’ll give you a lot more direction on the best coffee and tea choices in the next chapter, but feel free to enjoy those, either hot or cold, as well.

So how much water do you really need? The answer may surprise you. While drinking water regularly throughout the day is a sound strategy, if you drink water, coffee, or tea with meals and snacks, plus anytime you feel thirst coming on, chances are you’re well hydrated.

Contrary to popular belief, you don’t need to force down 8 to 10 glasses of water in addition to all your other food and drink choices. In fact, researchers have recently taken a closer look at the myths around water intake and found that very little was based in actual science. The latest guidelines from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) state that “the vast majority of healthy people adequately meet their daily hydration needs by letting thirst be their guide.”4

Another easy way to see if you need to drink more water is to do a quick urine check—it should be clear and have no odor (as opposed to being darker with a strong smell). A few exceptions to this rule: Children, the elderly, and people who are ill should not let thirst be their guide because they may not have fully functioning thirst responses. Likewise, those at high altitudes, in very hot temperatures, or exercising hard for a long time may need more water than thirst dictates.

If you’re a regular soda or beer drinker, switching to water can be one of the easiest ways to lose weight fast. Several years ago, I was counseling firefighters and police officers throughout the state of Massachusetts. In the first days of our meetings, I brought in my “sugar tubes” showing how much sugar (about 10 teaspoons) is in a 12-ounce can of soda. Several of these guys were drinking two or three cans of soda a day! That visual alone was enough to get a couple of the guys to stop cold turkey, and the results were fast and furious. A few lost about 20 pounds in 6 months! I’ve seen similar results for nightly beer drinkers, too. Check out the table below for some other examples of the poundage you can lose by cutting back on your brews.

DRINKING RESPONSIBLY GETS YOU ON THE FAST TRACK TO LEAN

| CUT OUT THIS | FOR THIS MANY CALORIES |

AND LOSE THIS MANY POUNDS IN A YEAR |

| 12-oz beer a night | 150 | 15 |

| 3 (5 oz each) glasses of wine a week | 300 | 4.5 |

| 12-oz soda each day | 150 | 15 |

| 2 Starbucks venti lattes (using 2% milk) a week |

480 | 7 |

| 12-oz Gatorade (Performance Series) after workouts 4 nights a week |

1,240 | 18.5 |

GREEN BENEFITS

After beef, bottled water may represent the single biggest, fastest change you can make to shrink your carbon footprint. In the cluttered beverage aisle these days it’s easy to forget that all this stuff is completely unnecessary.

Next time you’re in the supermarket, take a good hard look at the beverage and juice aisle. You’ll see the immense “cost of convenience” in action, to your waistline and your waste-line. That daily love affair with your barista, office vending machine, or smoothie bar can add up, too: Cups, lids, straws, napkins, stirrers, coffee sleeves, and all the other accessories you get nowadays affect not only price but also the carbon footprint of your brew.

You see, premade beverages do several things: They foster an increased desire for sweetness, add big bucks to your food bill, pack lots of extra weight onto your shopping trips (which means more gasoline needed to pull them home), and come in overwhelming levels of packaging.

Of course, the nutritionist in me absolutely sees the benefits of zero-calorie beverages. Flavored waters, diet sodas, seltzers, and other low-calorie or zero-calorie sweetened beverages can add flavor and variety to a diet without pouring on extra calories. They keep life flexible and fun. And they free up some more calories to go back on your plate. So zero-calorie is certainly a better choice if your sole goal is lean. But this book is about the intersection of personal and planetary health, and here’s another green truth: Zero-calorie doesn’t mean zero-impact.

First drawback: Liquid is one of the heavier types of food calories to ship, so it requires more fuel to transport than many, many other areas of your diet. That’s why “drinking responsibly” begins to take on a whole new meaning.

Second drawback: the packaging. If every human being on the planet adopted the average American’s drinking habits, we’d need another planet to sustain it, and quickly. Every second Americans toss 694 plastic bottles, totaling more than 60 million a day, and every day we dispose of 100 million aluminum steel cans (that’s enough to build a roof over all of New York City).5 Since less than 30 percent of those products are recycled, it creates a glut in our waste streams and has a “double warming” effect of breaking down into planet-warming gases.

Luckily, the solution is easy. Simply put, bottled water is choking the planet with both greenhouse gases and trash. When you drink it, you land squarely in the hot zone. While it’s pretty much “ditto” for the rest of the beverage aisle (excluding the exceptions I made above), we’ll concentrate on the issues as they pertain to water. Just keep in mind that they ring true for other packaged beverages as well.

In 2006, Americans guzzled more than 31 billion liters of bottled water, shelling out more than $15 billion in the process—more than they spent on iPods or movie tickets.6 That’s perfectly good money that you can now put toward your new green cuisine. And that’s 28 gallons of water for every man, woman, and child living in America, water that required more than 900,000 tons of plastic to manufacture all those bottles to bring it to you. And who knows how many of those were chillin’ in a nice 40°F cooler in a mini mart, the airport, or the food court before you decided to buy them?

In the United States alone, roughly 1 billion bottles of water are shipped around the country each week in ships, trains, and trucks; that’s equivalent to a weekly convoy of 37,800 18-wheelers delivering something we could get for much less fossil fuel simply by turning on the tap. What’s more, it’s a fast-growing category. Flavored water sales alone have climbed 35 percent since 2005.

Gulp. Want some more? Here are some other facts that I personally find hard to swallow.

- According to the Earth Policy Institute, the annual fossil fuel footprint of bottled water consumption in the United States is equivalent to more than 50 million barrels of oil— enough to run 3 million cars for 1 year.7

- Just manufacturing the roughly 30 billion plastic bottles used for water in the United States each year requires the equivalent of more than 17 million barrels of crude oil; transporting these bottles and selling them from chilled machines can double that, depending on where you live.

- Almost 40 percent of all US bottled water sales is just filtered tap water—water that is already perfectly safe to drink—sold at a premium. It’s bottled in petroleum-rich plastic and shipped around the country.

- The United States is the world’s number-one guzzler of bottled water, despite having the absolute safest water supply in the world (one out of six people in the world has no dependable, safe drinking water).

- Americans are actually paying up to four times as much per gallon for their designer H20 as they are for gasoline, and about 1,000 times more than they pay for tap water.

- “Lighter bottles, carbon offsets, carbon negative”—these are all shades of greenwashing when it comes to water. At the end of the day, we can get water in a much greener, cheaper, and equally safe way—the tap.

PAYING MORE FOR BOTTLED WATER THAN OIL8

| ITEM | COST PER LITER* | COST PER GALLON* |

| Fiji | $2.08 | $7.90 |

| Dasani | $1.29 | $4.90 |

| Aquafina | $1.59 | $6.04 |

| Regular unleaded gasoline | $4.08 | |

| Average municipal water supply | $0.01 |

*Water prices from Shaw’s Supermarket, 71 Dodge Street, Beverly, MA 01915, on June 17, 2008.

Ironically, 30 years ago, bottled water barely existed as a market. Today, Americans drink more bottled water than anyone in the world—at an immense cost to the planet and our own pocketbooks.

If you don’t like the taste of your tap water, or want extra insurance that your water is safe, then by all means get a filter. There are some great filters available that can give you fresh-tasting, clean water from your tap, such as a Brita pitcher filter, a PUR filter, or a Culligan Reverse Osmosis (RO) filter that goes right on your faucet.

Is there a carbon cost to tap water, too? Of course. But unless Americans are willing to go without water piped into their homes, their gyms, their offices, and their malls (remember, no piped water means no flush toilets—how likely is that?), piped water is a fixed cost that will be there regardless.

Luckily, it seems that people are getting the message. “Back to the Tap” initiatives are filtering across some of the largest cities in the country—with places such as New York City and San Francisco now banning bottled water at meetings of public officials, recognizing that it’s quickly filling up precious landfill space and draining tax coffers in one fell swoop.

FIVE WAYS TO MAKE TAP WATER TASTY

- Fill an ice cube tray with water and then add whole berries. They add gorgeous color, flavor, and antioxidants to your glass. If you can afford the calories, add a splash of 100 percent juice to the cubes as well.

- In winter, steep some of your favorite herbal tea, cool in the fridge, and add a bit of raw local honey and some citrus wedges for a sustainable and seasonal sipfest.

- Stir in fresh grated ginger, a mint sprig, and a squeeze of fresh tangerine juice for zing, vitamin C, and digestive health.

- Think spa water: Float sliced cucumbers or lime for a cleansing, refreshing change.

- Make a DIY seltzer. If you can’t give up the fizz, consider buying a home seltzer machine that lets you turn up the fizz on your tap water. It’s much greener than buying, schlepping, and then disposing of all those bottles (and ultimately cheaper, too).

I find that food changes can sometimes be difficult to make for even the most dedicated do-gooder; beverage changes, by comparison, can sometimes be more easily and quickly adapted. Luckily, drinking from the tap in a reusable cup is one of the easiest, quickest ways to cut your carbon footprint and food bill, and drinking water in lieu of high-calorie beverages such as designer coffee drinks, juices, and sodas will have you treading more lightly in other important ways, too—namely your weight.

Bottled water is a wonderful safety net and a lifesaving resource in times of crisis or emergency. In other regions of the world, it is a critical insurance against questionable water sources. But here in the United States, our daily reliance seems symbolic of how careless and wasteful our lifestyles have truly become. Let’s make it a habit to leave it where it belongs. Alone.

TAKE ACTION NOW

- Purchase nontoxic, reusable water bottles for you and your family. Stainless steel is another good alternative. Get your kids on board, too, with their own nontoxic eco-friendly water bottles. If you’re comfortable using something from your current stash of plastic workout or camping bottles, then by all means do so. You can use one in your car, stash it in your gym bag, or keep one handy at work.

- Bring a glass, mug, or cup to work and ditch the plastic and paper cups by the water cooler.

- Make a tasty antioxidant-rich brew. Brew up a batch of green or herbal tea for a boost of antioxidants and flavor; stick it in the fridge to cool. Garnish with citrus wedges in the winter and berries and mint in the summer.

- Use your existing bottled water wisely; save it for critical times rather than consuming it daily.

Now that we’ve tackled water, let’s move on to the other “W” that might be in your glass, wine.

Wine

In 2008, Americans became the number-one wine consumers in the world, surpassing even our wine-loving amis in France and Italy. If you enjoy wine, it can remain a healthy and delicious part of your lean and green lifestyle because it has so many positive health benefits and adds a wonderful dimension to the flavor of your meals.

LEAN BENEFITS

A bottle of wine is alive, teeming with compounds for your health and your heart, not to mention your taste buds. You have probably heard by now that drinking red wine in moderation is a healthy habit; this is because it contains powerful compounds called polyphenols that help keep your heart, brain, and arteries working effectively into ripe old age. A study from the University of Bordeaux found wine drinkers had a 35 percent reduction in death rates from cardiovascular disease, and a 24 percent reduction in death rates from cancer, compared to people who didn’t drink wine.9 Regular, moderate wine drinking also seems to cut your risk of stroke, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease.10 Think of it as Roto-Rooter for your arteries.

The key here is moderation: up to one glass per day for women and up to two for men. Calories climb quickly. A 5-ounce glass of red wine has about 100 calories—about as much as a slice of bread. Even if you are “moderate” all week, but drink several additional glasses over the weekend, you may be imbibing in the caloric equivalent of half a loaf of bread.

So nix the temptation to tell yourself it’s “nutritionist-approved” while pouring that second (or third) glass, as there’s no additional health benefit. If you’re working hard to lose weight but still want to keep the wine in your diet, as many of my clients do, here’s the straight talk: To fit in those extra calories, you gotta be exercising. Really exercising.

Whatever you do, do not simply cut other foods out, especially healthy foods, in order to make room for wine. You are less likely to shed pounds, and you may be compromising your nutrition, your body’s metabolic rate, and your health. Especially if you are postmenopausal, you may find it difficult to maintain your current weight (and even harder to lose weight) if you include alcohol. Be sure to make the rest of your calories count, with nutrient-dense, moderate-calorie choices. If you do choose to include wine, watch your portions and be sure to keep active and exercise.

Note: If you choose not to drink alcohol, you can still reap some of the same cardiovascular benefits by enjoying 4 ounces of 100 percent grape juice every day, which is a great strategy for your kids, too.

Also, just an aside here for readers scouring the chapter looking for a discussion of other alcoholic drinks: Beer and spirits are not officially on my lean and green list. While both, when consumed in modest amounts, have some positive effects on “good” HDL cholesterol, the Go Green Get Lean Diet promotes wine instead because wine will give you those same benefits plus many others. And beer and spirits, like all alcohol, come in high-calorie packages, so they’re some of the fastest ways to pack on the pounds. From a green standpoint, the same production, shipping, transportation, and refrigeration (as well as packaging and marketing) issues all apply.

That being said, if you’re not a wine drinker and you can afford the extra calories (as both beer and spirits are classic “empty calories” from a nutrition and weight standpoint), then wet your whistle with a local microbrew (it’s much easier to find local beer dotting the country than it is wine) and use Your L.E.A.N. Cheat Sheet (see page 154) as a guide to greening your cocktail.

GREEN BENEFITS

Sipping a French Bordeaux or a California Cab may be heaven to your arteries and your palate, but which one is better for the planet? The answer may surprise you.

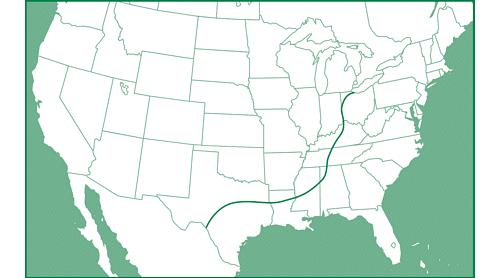

While obvious for the folks living in California or France, the answer becomes murkier for those of us who are landlocked. A 2007 study that looked at the carbon footprint of wine found that because of the weight of shipping glass bottles of liquid, transportation to the consumer was the single biggest carbon factor, even over whether or not the wine was organic. Which means that if you live east of Columbus, Ohio, drinking like a “locavore” means it’s greener to fill your glass with that French Bordeaux.11 Ooh la la.

Here are a few other tips to keep in mind.

- Magnums are more energy efficient; half bottles are much less efficient.

- Boxed wines are among the most efficient of all.

- Choose standard bottles rather than thicker ones (which you often find at the high-end premium range), because they are more energy efficient.

- Companies that ship wine in bulk closer to the consumer and then bottle are greener (this saves on the cost of transporting all the bottles), so when in doubt, ask.

- Buying wine directly from the vineyard is a high-carbon habit, as wineries often overnight cases to clients around the country via air (to minimize temperature fluctuations and ensure product quality).

- Organic, sustainable, or biodynamic wines make a small difference to overall carbon footprint when compared to transportation.

THE GLASS IS ALWAYS GREENER ON THE OTHER SIDE

This map shows the approximate break-even point between Bordeaux and Napa wines. If you live west of the line, California wine will likely have a lower carbon footprint. East of the line, and France is a better bet.

Of course, there are some practical realities to this new approach to choosing the greenest wines, such as the value of the dollar against European currency, for one. Or the marketing challenge of trying to persuade people to unscrew a box cap rather than pop open a cork. My husband, a self-proclaimed oenophile, visibly cringed at my suggestion for moving to a wine box in the name of saving the planet. Might people draw a line in the sand at the thought of getting their wine from a milk carton–like container (one of the other suggestions the study authors proposed)? I certainly know a few who would, and I believe I live with one of them. (Heck, if I’m really honest, I may even be one of them.)

CARBON EMISSIONS OF THREE WINES HEADING TO CHICAGO12

| Boutique Napa winery | 4.5 kg/bottle | (overnight air) |

| France | 2.12 kg/bottle | (boat, truck) |

| Australia | 3.44 kg/bottle | (boat, then train or truck) |

You may decide instead that you’re more than willing to cut back on a few steaks a year, or to really always pass on the bottled water at the office meetings from now on, or to bike to the wine bar instead of drive (probably a better idea anyway) and consider these savings a “balancing out” of your love of wine served the old-fashioned way. After all, the vast health benefits of wine in moderation make it worth including if you can. As for my house, we still drink our wine from a bottle, but we stick to wines from California and Oregon, and are now pairing it with much more vegetarian and green cuisine.

TAKE ACTION NOW

- Check out the US map and see what the greenest option is for you.

- Buy your wine from your local wine shop (ideally, stock up to maximize your personal trip) rather than having it shipped from the Internet or from a mailing list.

- If you live in a wine-producing region, try to sip like a local.

- Buy larger magnums if you can, don’t order or buy half bottles, and consider buying wine in a box.

ORGANIC, SUSTAINABLE, AND BIODYNAMIC WINES

Many wineries, from boutique to large well-known brands, are dipping their toes into sustainable, organic, and biodynamic practices, finding that organic agriculture can yield better results for the land and the wine. Most wineries don’t necessarily bang the organic drum loudly as a marketing tool, and many don’t even mention it on their labels, either because they may not be officially “certified organic,” or because they want to compete with the mainstream on the merits of the wine itself rather than be seen in only the “organics” category. While you will still reap health benefits from standard red wine, and these programs may not nudge the carbon count down significantly per se, they certainly provide other numerous benefits to the planet. Here’s a quick look at the terms and what they mean.

Sustainable: The wine producer follows a voluntary sustainability program established by the Wine Institute that has a step-by-step guide to “best practices,” where producers then receive a sustainability rating of 1 to 4 (4 being the best). So far, more than 1,100 wineries have evaluated their own practices, according to the Wine Institute. One key difference is that the application of synthetic compounds and pesticides is allowed but discouraged.

Organic: Wine has to meet federal organic guidelines and certifications. A very small percentage of vineyards currently have this certification, as it is costly and time-consuming. In addition to farming organically, no sulfur (a key component of the aging process) can be added to the wines.

Biodynamic: An approach to agriculture that treats the soil as a living entity and focuses on balancing the entire system, aligning with nature’s cycles, and using natural predator/prey systems. Part mystical, part practical, the philosophy has advocates who claim it brings the soil into perfect alignment, making for delicious and sustainable wine.

Juice

Truly fresh-squeezed fruit or vegetable juice tastes wonderful and can refresh and awaken you. Its live enzymes provide a powerful cocktail of nutrients. And juicing can be a great way to harness the power of foods that have been used medicinally in alternative medicine for centuries (e.g., beet juice for liver cleansing, celery juice for blood pressure, ginger to soothe your stomach).

LEAN BENEFITS

Juice is one of the classic “in moderation can be good for you” foods. For many people, 4 to 6 ounces of 100 percent juice can be a quick, easy, reliable, and nutritious way to sneak in an extra serving of disease-fighting fruits and veggies. And let’s face it: Americans are notorious underachievers when it comes to eating enough fruits and veggies; juice offers a valuable shortcut. But as with everything, the right kind, in the right amounts, is key to getting the results you want.

If you can’t afford the extra calories, are diabetic, or are especially prone to blood sugar swings, then definitely skip the juice. Eat the whole fruit instead. You’ll get more nutrition and phytochemicals in a lower-calorie package, plus loads of fiber, which slims you down and fills you up. The other advantage is that eating the whole fruit will work with your biology and your brain to help you eat less later (remember, liquid calories don’t really register with your brain).

Drink cleanly by choosing only 100 percent juice. Once you leave 100 percent juice, it’s a slippery slope down to “liquid candy.”

For children, stick with no more than 4 to 6 ounces of 100 percent juice per day. More may interfere with appetite, may push out other important beverages such as water and milk, and may be training them to like only sweet drinks. Even the American Academy of Pediatrics issued guidelines in 2001 advising no more than 6 ounces per day for kids, having seen an alarming increase in juice consumption.

Skip the added extras. These include vitamins, immune boosters, and mineral additions. For one thing, the juice is apt to be in a higher-carbon package. Second, you’re probably going to pay more for them, and often only small amounts are added for marketing purposes; ignore the hype on the labels and eat a healthy diet instead. Two possible exceptions: calcium (if you don’t take a calcium supplement, do not include calcium-rich foods regularly, and are at risk for osteoporosis) and plant stanols (if you have high cholesterol).

GREEN BENEFITS

Juice still tends to be a high-carbon part of your diet because of the waste associated with it (consider that it typically takes about four oranges to make 6 ounces of juice). And if your juice is made somewhere else and shipped to you (instead of buying it freshly made at a juice bar, for instance), there’s the added carbon of shipping heavy liquids. So here’s what you need to know for a more sustainable squeeze.

Buy 100 percent frozen juice concentrate as the gold standard, if it’s an option. It’s the best for nutrition, cost, and significant carbon savings (you’re not shipping all that water around).

Stick to American beauties for another winning lean and green overlap (revisit the list of American beauties on page 137 in Chapter 9). Exotic superfruit juices don’t give you any more help in soothing American stress, and likely have a higher carbon footprint and a higher price tag. Good old-fashioned Concord grape juice, pomegranate, cherry, and blueberry juice, in contrast, have ample research showing clear health benefits.

Check that OJ label. Avoid buying conventional juice that is grown in tropical areas such as Brazil or Costa Rica. According to the Rainforest Action Network, conventional oranges grown in Brazil and other South American countries are often grown on areas of rainforest that have been burned and cleared to plant these trees, removing a critical “carbon cooler”—a double carbon footprint whammy.

Shop for eco-chic labels. If you do decide to swig more exotic juices, or common juice that’s grown in exotic locales, be extra sure to sip sustainably and organically, so you’re not destroying tropical areas to fuel your zest for some zingy new brew.

Pick minimal packaging. Packaging in this category can be outrageous. Avoid single-serving bottles, juice boxes, and any “power juices” in annoyingly (to me) small sizes in the supermarket, sometimes shrink-wrapped to boot. (I can’t help but notice many of these exotic juices come in small bottles—probably so you won’t pay attention to how much you’re paying per ounce.) This ups the carbon cost of shipping the juice around, because the packaging-to-product ratio is so skewed. So buy in bulk if you can. And juicing yourself will minimize the packaging big time. And, of course, recycle that packaging!

Squeeze it yourself. If you’re an OJ or grapefruit junkie, consider investing in a hand-pressed juicer for amazingly fresh flavor, and then start squeezin’ the old-fashioned way. It’s super easy and kids love it! A great example of quality over quantity, it cuts your carbon footprint and packaging. (Two added pluses: You’ll burn a few extra calories while you’re at it, and it will be easier to stick to 4 to 6 ounces because you’ll be too busy to stand there and squeeze more.)

Soda

How can I put this lightly? Soda sucks.

There is no room for soda, diet soda, “health drinks,” or energy drinks on the Go Green Get Lean Diet. Ignore them. There’s no nutritional benefit to soda and there are lots of nutritional drawbacks: the added empty calories, the fact that they perpetuate a continued drive to seek sweetness, the possible interference with the calcium to phosphorus balance in your body, and their ability to zap your vitality and wreak havoc on your blood sugar. Unlike other high-carbon foods that at least provide a specific and measurable health benefit (e.g., fresh Alaskan salmon, a glass of fresh-squeezed juice), it’s harder to salve your eco-guilt by drinking greenwashed diet soda that is manufactured using wind power.

Energy drinks are even worse. Essentially the pimped-out version of sodas, they jack up the calories, the sugar, and the caffeine in a major way. They induce a high-stress state called fight or flight in your body that taxes your adrenal glands and can overwhelm your body’s stress response over time. Talk about an immediate place to trim; America’s food supply provides about 200 calories per person each day in soft drinks alone, in the form of high-fructose corn syrup. Soft drinks are the single biggest source of added sugars in the American diet today, composing about 33 percent of the carbohydrates in people’s diets. No wonder we have a weight problem.

Since 1978, soda consumption in the United States has tripled for boys and doubled for girls. According to the National Soft Drink Association (now renamed a more benign-sounding “American Beverage Association”), consumption of soft drinks is the equivalent of more than 600 cans (12 ounces each) per American per year. Young males ages 12 to 29 are the biggest consumers at more than 160 gallons per year—that’s almost 2 quarts per day.

LEAN BENEFITS

Drink diet soda, get lean, right? Wrong. Most people drink diet soda and “health” beverages to help control their weight. The problem is, the research actually points in the opposite direction—that people drinking these beverages aren’t any thinner, and that the more you drink, the more you may actually end up gaining. An 8-year study from the University of Texas found that for diet soda drinkers, the risk of overweight climbed by a whopping 41 percent for subjects who drank one to two diet sodas a day.13

To me, this group of products seems a particularly sneaky subset of the soda category. They appeal to your desire to lose weight. They may add a few vitamins, minerals, or exotic ingredients to make them seem healthy and convince you that they provide some advantage over, say, water. They may tempt you with “light” versions, which are essentially watered-down versions of the original that you pay the same price for, sometimes with a sweetener such as sucralose thrown in to fool your taste buds.

Diet soda and these “health” drinks are still a part of the global industrial food chain, requiring all that energy to bring to you, and you get little or no nutrition or energy in return. And remember that you can easily obtain the small smattering of vitamins any of these might provide by instead eating whole foods, taking your multivitamin, or having some whole grain breakfast cereal. So can the soda. And remember, zero calories doesn’t mean zero impact.

GREEN BENEFITS

A 12-ounce aluminum can is derived from metals mined halfway across the globe. The can itself, in fact, requires 1,643 kilocalories of fossil fuel energy to make, which is usually more than 10 times the food energy that’s contained in it (food energy, by the way, in the form of high-fructose corn syrup—nasty). Fill the can with diet soda instead of regular, and you’ve just spent more than 1,600 fossil fuel calories to bring you precisely zero.14 Zilch. Totally wasteful.

SKIP THE ARTIFICIAL SWEETENERS TO BE LEAN AND GREEN

I have changed my opinion of artificial sweeteners over the years I’ve been a dietitian. (Full disclosure, I once did some media work for aspartame, but withdrew after I realized that as I personally didn’t use it or give it to my children, I could not endorse its use, or the use of any other artificial sweetener for that matter.) Artificial sweeteners are not part of a lean and green lifestyle because they are industrial ingredients; they are often found in industrial foods; they keep your palate focused on sweet foods and beverages; and they don’t appear to provide a real advantage to weight loss (there is certainly much data that has found weight loss benefits of several artificial sweeteners, but these studies have subjects on a calorie-controlled diet that includes some artificially sweetened products; of course people are likely to lose weight when following a reduced-calorie plan).

“Artificial sweeteners may give you the illusion of doing something useful to avoid sugars and control your calorie intake,” writes Marion Nestle in What to Eat, “but it does not take much food to make up for the calories you save, and the sweeteners do not help with what really matters in weight control: eating less and being more active.” Exactly. Avoid them.

And though recycling just one aluminum beverage can saves enough electricity to power your TV for 3 hours, we can’t just “recycle away” the consequences of our soda habit; recycling still requires energy and water resources. Then there’s the teensie inconvenient fact that about $2 billion in recyclable aluminum beverage cans is tossed into landfills every year.15 It’s still taking from the system, using energy and gobbling resources. And if all that is happening just so you can “have your cake and eat it too” by sipping sweet soda without any caloric consequences, consider the size of your own carbon footprint to be a lot bigger than it should be. So take less—and start looking better, saving money, lightening your carbon footprint, and feeling more beautylicious because you know you’re doing right by yourself and the planet. In my experience, I have found that people often simply start feeling a lot better once they can the soda completely, even the diet stuff.

In the end, it’s pretty simple and straightforward, and deep down you probably know that you should be drinking less anyway. So stay focused on the benefits of greening your glass. It will go a long way toward simplifying your shopping trips; it will save your back from lugging all those liquids into your pantry; it will help rebalance your palate away from the constant craving for sweetness; and it will trim unwanted carbon and pounds from your life.

TAKE ACTION NOW

- When you do splurge on sodas, look for a locally made brand with clean ingredients. Buy in bulk and recycle every stitch of packaging.

- Choose fountain drinks rather than single-serving bottles.

- Choose glass over aluminum cans because they’re about twice as energy efficient to produce.

- Make a DIY soda/seltzer at home. You can save money and carbon by investing in a home soda-making machine. (But you won’t save any calories.)

- If you absolutely must flavor your beverage, buy the concentrated packets and add them to your own water. Not only is it more cost effective, but you’ll also be saving the carbon cost of shipping all that liquid volume.

Perhaps nowhere in the grocery aisles is it as clear just how troubled our calorie intake has become. Perhaps in no area of our diets is it as hard to ignore the clear intersection of weight and warming problems caused by the daily habits of the American consumer. Thank goodness that the way out of both is clear and straightforward. Your own best defense against belly bloat, and Earth’s best defense against frivolous waste and carbon burn, are one and the same: sip sustainably.

See? I told you it was easy.

Have you saved room for dessert? Good. Now let’s get talking about those green treats.

Notes - Chapter 13

1. http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/report/.

2. D.P. DiMeglio and R.D. Mattes, “Liquid Versus Solid Carbohydrate: Effects on Food Intake and Body Weight,” International Journal of Obesity (2000) 24: 794–800.

3. S.P. Fowler, 65th Annual Scientific Sessions, American Diabetes Association, San Diego, June 10–14, 2005; Abstract 1058-P, Sharon P. Fowler, MPH, University of Texas Health Science Center School of Medicine, San Antonio; and T.L. Davidson, “Artificial Sweeteners May Damage Diet Efforts,” Int J Obes (July 2004) 28:933–55.

4. Institute of Medicine, “Dietary Reference Intakes: Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate,” National Academies Press, February 11, 2004.

5. From National Geographic’s “The Human Footprint,” aired April 13, 2008. http://ngcblog.nationalgeographic.com/ngcblog/2008/03/. Accessed August 28, 2008.

6. C. Fishman, “Message in a Bottle,” Fast Company, Issue 117 (July 2007) 110.

7. Energy Information Administration: http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/oog/info/gdu/ gasdiesel.asp. Accessed June 17, 2008.

8. Janet Larson, “Bottled Water Boycotts: Back-to-the-Tap Movement Gains Momentum,” December 7, 2007, Earth Policy Institute: http://www.earth-policy. org/Updates/2007/Update68.htm.

9. S.C. Renaud et al., “Alcohol and Mortality in Middle-Aged Men from Eastern France,” Epidemiology (1998) 9(2):184–88.

10. T. Truelsen et al., “Intake of Beer, Wine, and Spirits and Risk of Stroke: The Copenhagen City Heart Study,” Stroke (1998) 29(12):2467–72; Swedish Research Council, “Wine May Protect Against Dementia, Study Suggests” ScienceDaily (2008, April 13). Retrieved June 15, 2008, from http://www.sciencedaily.com.

11. T. Colman and P. Pastor, “Red, White and ‘Green’: The Cost of Carbon in the Global Wine Trade,” American Association of Wine Economists, AAWE Working Paper No. 9. October 2007.

12. Ibid.

13. S.P. Fowler, 65th Annual Scientific Sessions, American Diabetes Association, Abstract 1058-P; T.L. Davidson, “Artificial Sweeteners,” 933–55.

14. Pimentel, 1979.

15. http://www.recycle.novelis.com/Recycle/EN/Educators/Benefits+of+Alumi.