– From Mr Bunnsy Has An Adventure

THE CROWD CLUSTERED into the Rathaus’s council hall. Most of it had to stay outside, craning over other people’s heads to see what was going on.

The town council was crammed around one end of their long table. A dozen or so of the senior rats were crouched at the other end.

And, in the middle, was Maurice. He was suddenly there, leaping up from the floor.

Hopwick the clockmaker glared at the other members of the council. ‘We’re talking to rats!’ he snapped, trying to make himself heard above the hubbub. ‘We’ll be a laughing stock if this gets out! “The Town That Talked To Its Rats”. Can’t you just see it?’

‘Rats aren’t there to be spoken to,’ said Raufman the bootmaker, prodding the mayor with a finger. ‘A mayor who knew his business would send for the rat-catchers!’

‘According to my daughter, they are locked in a cellar,’ said the mayor. He stared at the finger.

‘Locked in by your talking rats?’ said Raufman.

‘Locked in by my daughter,’ said the mayor, calmly. ‘Take your finger away, Mr Raufman. She’s taken the watchmen down there. She’s making very serious allegations, Mr Raufman. She says there’s a lot of food stored under their shed. She says they’ve been stealing it and selling it to the river traders. The head rat-catcher is your brother-in-law, isn’t he, Mr Raufman? I remember you were very keen to see him appointed, weren’t you?’

There was a commotion outside. Sergeant Doppelpunkt pushed his way through, grinning broadly, and laid a big sausage on the table.

‘One sausage is hardly theft,’ said Raufman.

There was rather more commotion in the crowd, which parted to reveal what was, strictly speaking, a very slowly moving Corporal Knopf. This fact only became clear, though, when he’d been stripped of three bags of grain, eight strings of sausages, a barrel of pickled beetroot and fifteen cabbages.

Sergeant Doppelpunkt saluted smartly, to the sound of muffled swearing and falling cabbages. ‘Requesting permission to take six men to help us bring up the rest of the stuff, sir!’ he said, beaming happily.

‘Where are the rat-catchers?’ said the mayor.

‘In deep … trouble, sir,’ said the sergeant. ‘I asked them if they wanted to come out, but they said they’d like to stay in there a bit longer, thanks all the same, although they’d like a drink of water and some fresh trousers.’

‘Was that all they said?’

Sergeant Doppelpunkt pulled out his notebook. ‘No, sir, they said quite a lot. They were crying, actually. They said they’d confess to everything in exchange for the fresh trousers. Also, sir, there was this.’

The sergeant stepped out and came back with a heavy box, which he thumped down onto the polished table. ‘Acting on information received from a rat, sir, we took a look under one of the floor-boards. There must be more’n two hundred dollars in it. Ill-gotten gains, sir.’

‘You got information from a rat?’

The sergeant pulled Sardines out of his pocket. The rat was eating a biscuit, but he raised his hat politely.

‘Isn’t that a bit … unhygienic?’ said the mayor.

‘No, guv, he’s washed his hands,’ said Sardines.

‘I was talking to the sergeant!’

‘No, sir. Nice little chap, sir. Very clean. Reminds me of a hamster I used to have when I was a lad, sir.’

‘Well, thank you, sergeant, well done, please go and—’

‘His name was Horace,’ added the sergeant helpfully.

‘Thank you, sergeant, and now—’

‘Does me good to see little cheeks bulging with grub again, sir.’

‘Thank you, sergeant!’

When the sergeant had left, the mayor turned and stared at Mr Raufman. The man had the grace to look embarrassed.

‘I hardly know the man,’ he said. ‘He’s just somebody my sister married, that’s all! I hardly ever see him!’

‘I quite understand,’ said the mayor. ‘And I’ve no intention of asking the sergeant to go and search your larder,’ and he gave another little smile, and a sniff, and added, ‘yet. Now, where were we?’

‘I was about to tell you a story,’ said Maurice.

The town council stared at him.

‘And your name is—?’ said the mayor, who was feeling in quite a good mood now.

‘Maurice,’ said Maurice. ‘I’m a freelance negotiator, style of thing. I can see it’s difficult for you to talk to rats, but humans like talking to cats, right?’

‘Like in Dick Livingstone?’ said Hopwick.

‘Yeah, right, him yeah, and—’ Maurice began.

‘And Puss in Boots?’ said Corporal Knopf.

‘Yeah, right, books,’ said Maurice, scowling. ‘Anyway … cats can talk to rats, OK? And I’m going to tell you a story. But first, I’m going to tell you that my clients, the rats, will all leave this town if you want them to, and they won’t come back. Ever.’

The humans stared at him. So did the rats.

‘Will we?’ said Darktan.

‘Will they?’ said the mayor.

‘Yes,’ said Maurice. ‘And now, I’m going to tell you a story about the lucky town. I don’t know its name yet. Let’s suppose my clients leave here and move down river, shall we? There are lots of towns on this river, I’ll be bound. And somewhere there’s a town that’ll say, why, we can do a deal with the rats. And that will be a very lucky town, because then there’ll be rules, see?’

‘Not exactly, no,’ said the mayor.

‘Well, in this lucky town, right, a lady making, as it might be, a tray of cakes, well, all she’ll need to do is shout down the nearest rat hole and say, “Good morning, rats, there’s one cake for you, I’ll be much obliged if’n you didn’t touch the rest of them”, and the rats will say “Right you are, missus, no problem at all”. And then—’

‘Are you saying we should bribe the rats?’ said the mayor.

‘Cheaper than pipers. Cheaper than rat-catchers,’ said Maurice. ‘Anyway, it’ll be wages. Wages for what, I hear you cry?’

‘Did I cry that?’ said the mayor.

‘You were going to,’ said Maurice. ‘And I was going to tell you that it’d be wages for … for vermin control.’

‘What? But rats are ver—’

‘Don’t say it!’ said Darktan.

‘Vermin like cockroaches,’ said Maurice, smoothly. ‘I can see you’ve got a lot of them here.’

‘Can they talk?’ said the mayor. Now he had the slightly hunted expression of anyone who’d been talked to by Maurice for any length of time. It said ‘I’m going where I don’t want to go, but I don’t know how to get off’.

‘No,’ said Maurice. ‘Nor can the mice, and nor can norma— can other rats. Well, vermin’ll be a thing of the past in that lucky town, because its new rats will be like a police force. Why, the Clan’ll guard your larders – sorry, I mean the larders in that town. No rat-catchers required. Think of the savings. But that’ll only be the start. The woodcarvers will be getting richer, too, in the lucky town.’

‘How?’ said Hauptmann the woodcarver, sharply.

‘Because rats will be working for them,’ said Maurice. ‘They have to gnaw all the time to wear their teeth down, so they might as well be making cuckoo clocks. And the clockmakers will be doing well, too.’

‘Why?’ said Hopwick the clockmaker.

‘Tiny little paws, very good with little springs and things,’ said Maurice. ‘And then—’

‘Would they just do cuckoo clocks, or could they do other stuff?’ said Hauptmann.

‘– and then there’s the whole tourism aspect,’ said Maurice. ‘For example, the Rat Clock. You know that clock they’ve got in Bonk? In the town square? Little figures come out every quarter of an hour and bang the bells? Cling bong bang, bing clong bong? Very popular, you can get postcards and everything. Big attraction. People come a long way just to stand there waiting for it. Well, the lucky town will have rats striking the bells!’

‘So what you’re saying,’ said the clockmaker, ‘is that if we— that is, if the lucky town had a special big clock, and rats, people might come to see it?’

‘And stand around waiting for up to a quarter of an hour,’ said someone.

‘A perfect time to buy hand-crafted models of the clock,’ said the clockmaker.

People began to think about this.

‘Mugs with rats on,’ said a potter.

‘Hand-gnawed souvenir wooden cups and plates,’ said Hauptmann.

‘Cuddly toy rats!’

‘Rats-on-a-stick!’

Darktan took a deep breath. Maurice said, quickly, ‘Good idea. Made of toffee, naturally.’ He glanced towards Keith. ‘And I expect the town would want to employ its very own rat piper, even. You know. For ceremonial purposes. “Have your picture drawn with the Official Rat Piper and his Rats”, sort of thing.’

‘Any chance of a small theatre?’ said a little voice.

Darktan spun around. ‘Sardines!’ he said.

‘Well, guv, I thought if everyone was getting in on the act—’ Sardines protested.

‘Maurice, we ought to talk about this,’ said Dangerous Beans, tugging at the cat’s leg.

‘Excuse me a moment,’ said Maurice, giving the mayor a quick grin, ‘I need to consult with my clients. Of course,’ he added, ‘I’m talking about the lucky town. Which won’t be this one because, of course, when my clients move out some new rats will move in. There are always more rats. And they won’t talk, and they won’t have rules, and they’ll widdle in the cream and you’ll have to find some new rat-catchers, ones you can trust, and you won’t have as much money because everyone will be going to the other town. Just a thought.’

He marched down the table and turned to the rats.

‘I was doing so well!’ he said. ‘You could be on ten per cent, you know? Your faces on mugs, everything!’

‘And is this what we fought for all night?’ spat Darktan. ‘To be pets?’

‘Maurice, this isn’t right,’ said Dangerous Beans. ‘Surely it is better to appeal to the common bond between intelligent species than—’

‘I don’t know about intelligent species. We’re dealing with humans here,’ said Maurice. ‘Do you know about wars? Very popular with humans. They fight other humans. Not hugely big on common bonding.’

‘Yes, but we are not—’

‘Now listen,’ said Maurice. ‘Ten minutes ago these people thought you were pests. Now they think you’re … useful. Who knows what I can have them thinking in half an hour?’

‘You want us to work for them?’ said Darktan. ‘We’ve won our place here!’

‘You’ll be working for yourself,’ said Maurice. ‘Look, these people aren’t philosophers. They’re just … everyday. They don’t understand about the tunnels. This is a market town. You’ve got to approach them the right way. Anyway, you will keep other rats away, and you won’t go around widdling in the jam, so you might as well get thanked for it.’ He tried again. ‘There’s going to be a lot of shouting, right, yeah. And then sooner or later you have to talk.’ He saw the bewilderment still glazing their eyes, and turned to Sardines in desperation. ‘Help me,’ he said.

‘He’s right, boss. You’ve got to give ’em a show,’ said Sardines, dancing a few steps nervously.

‘They’ll laugh at us!’ said Darktan.

‘Better laugh than scream, boss. It’s a start. You gotta dance, boss. You can think and you can fight, but the world’s always movin’, and if you wanna stay ahead you gotta dance.’ He raised his hat and twirled his cane. On the other side of the room, a couple of humans saw him and chuckled. ‘See?’ he said.

‘I’d hoped there was an island somewhere,’ said Dangerous Beans. ‘A place where rats could really be rats.’

‘And we’ve seen where that leads,’ said Darktan. ‘And, you know, I don’t think there’re any wonderful islands in the distance for people like us. Not for us.’ He sighed. ‘If there’s a wonderful island anywhere, it’s here. But I’m not intending to dance.’

‘Figure of speech, boss, figure of speech,’ said Sardines, hopping from one foot to the other.

There was a thump from the other end of the table. The mayor had hit it with his fist. ‘We’ve got to be practical!’ he was saying. ‘How much worse off can we be? They can talk. I’m not going to go all through this again, understand? We’ve got food, we’ve got a lot of the money back, we survived the piper … these are lucky rats …’

The figures of Keith and Malicia loomed over the rats.

‘It sounds as if my father’s coming round to the idea,’ said Malicia. ‘What about you?’

‘Discussions are continuing,’ said Maurice.

‘I … er … I’m sorr … er … look, Maurice told me where to look and I found this in the tunnel,’ said Malicia. The pages were stuck together, and they were all stained, and they had been sewn together by a very impatient person, but it was still recognizable as Mr Bunnsy Has An Adventure. ‘I had to lift up a lot of drain gratings to find all the pages,’ she said.

The rats looked at it. Then they looked at Dangerous Beans.

‘It’s Mr Bunn—’ Peaches began.

‘I know. I can smell it,’ said Dangerous Beans.

The rats all looked again at the remains of the book.

‘Maybe it’s just a pretty story,’ said Sardines.

‘Yes,’ said Dangerous Beans. ‘Yes.’ He turned his misty pink eyes to Darktan, who had to stop himself from crouching, and added: ‘Perhaps it’s a map.’

If it was a story, and not real life, then humans and rats would have shaken hands and gone on into a bright new future.

But since it was real life, there had to be a contract. A war that had been going on since people first lived in houses could not end with just a happy smile. And there had to be a committee. There was so much detail to be discussed. The town council were on it, and most of the senior rats, and Maurice marched up and down the table, joining in.

Darktan sat at one end. He really wanted to sleep. His wound ached, his teeth ached, and he hadn’t eaten for ages. For hours the argument flowed back and forwards over his drooping head. He didn’t pay attention to who was doing the talking. Most of the time, it seemed to be everyone.

‘Next item: compulsory bells on all cats. Agreed?’

‘Can we just get back to clause thirty, Mr, er, Maurice? You were saying killing a rat would be murder?’

‘Yes. Of course.’

‘But it’s just—’

‘Talk to the paw, mister, ’cos the whiskers don’t want to know!’

‘The cat is right,’ said the mayor. ‘You’re out of order, Mr Raufman! We’ve been through this.’

‘Then what about if a rat steals from me?’

‘Ahem. Then that’ll be theft, and the rat will have to go before the justices.’

‘Oh, young—?’ said Raufman.

‘Peaches. I’m a rat, sir.’

‘And … er … and the Watch officers will be able to get down the rat tunnels, will they?’

‘Yes! Because there will be rat officers in the Watch. There’ll have to be,’ said Maurice. ‘No problem!’

‘Really? And what does Sergeant Doppelpunkt think about that? Sergeant Doppelpunkt?’

‘Er … dunno, sir. Could be all right, I suppose. I know I couldn’t get down a rat hole. We’ll have to make the badges smaller, of course.’

‘But surely you wouldn’t suggest a rat officer could be allowed to arrest a human?’

‘Oh, yes, sir,’ said the sergeant.

‘What?’

‘Well, if your rat’s a proper sworn-in watchman … I mean, a watchrat … then you can’t go around saying you’re not allowed to arrest anyone bigger than you, can you? Could be useful, a rat watchman. I understand they have this trick where they run up your trouser leg—’

‘Gentlemen, we should move on. I suggest this one goes to the sub-committee.’

‘Which one, sir? We’ve already got seventeen!’

There was a snort from one of the councillors. This was Mr Schlummer, who was 95 and had been peacefully asleep all morning. The snort meant that he was waking up.

He stared at the other side of the table. His whiskers moved.

‘There’s a rat there!’ he said, pointing. ‘Look, mm, bold as brass! A rat! In a hat!’

‘Yes, sir. This is a meeting to talk to the rats, sir,’ said the person beside him.

He looked down and fumbled for his glasses. ‘Wassat?’ he said. He looked closer. ‘Here,’ he said, ‘aren’t, mm, you a rat, too?’

‘Yes, sir. Name of Nourishing, sir. We’re here to talk to humans. To stop all the trouble.’

Mr Schlummer stared at the rat. Then he looked across the table at Sardines, who raised his hat. Then he looked at the mayor, who nodded. He looked at everyone again, his lips moving as he tried to sort this out.

‘You’re all talking?’ he said, at last.

‘Yes, sir,’ said Nourishing.

‘So … who’s doing the listening?’ he said.

‘We’re getting round to that,’ said Maurice.

Mr Schlummer glared at him. ‘Are you a cat?’ he demanded.

‘Yes, sir,’ said Maurice.

Mr Schlummer slowly digested this point too. ‘I thought we used to kill rats?’ he said, as if he wasn’t quite certain any more.

‘Yes, but, you see, sir, this is the future,’ said Maurice.

‘Is it?’ said Mr Schlummer. ‘Really? I always wondered when it was going to happen. Oh, well. Cats talk now, too? Well done! Got to move with the, mm, the … things that move, obviously. Wake me up when they bring the, mm, tea in, will you, puss?’

‘Er … it’s not allowed to call cats “puss” if you’re over ten years old, sir,’ said Nourishing.

‘Clause 19b,’ said Maurice, firmly. ‘“No one is to call cats by silly names unless they intend to give them an immediate meal”. That’s my clause,’ he added, proudly.

‘Really?’ said Mr Schlummer. ‘My word, the future is strange. Still, I daresay everything needed sorting out …’

He settled back in his chair, and after a while began to snore.

Around him the arguments started again, and kept going. A lot of people talked. Some people listened. Occasionally, they agreed … and moved on … and argued. But the piles of paper on the table grew bigger, and looked more and more official.

Darktan forced himself to wake up again, and realized that someone was watching him. At the other end of the table, the mayor was giving him a long, thoughtful stare.

As he watched, the man leaned back and said something to a clerk, who nodded and walked around the table, past the arguing people, until he reached Darktan.

He leaned down. ‘Can … you … un-der-stand … me?’ he said, pronouncing each word very carefully.

‘Yes … be-cause … I’m … not … stu-pid,’ said Darktan.

‘Oh, er … the mayor wonders if he can see you in his private office,’ said the clerk. ‘The door over there. I could help you down, if you like.’

‘I could bite your finger, if you like,’ said Darktan. The mayor was already walking away from the table. Darktan slid down and followed him. No one paid any attention to either of them.

The mayor waited until Darktan’s tail was out of the way and carefully shut the door.

The room was small and untidy. Paper occupied most flat surfaces. Bookcases filled several of the walls; extra books and more paper were stuffed in between the tops of the books and any space in the shelves.

The mayor, moving with exaggerated delicacy, went and sat in a big, rather tatty swivel chair, and looked down at Darktan. ‘I’m going to get this wrong,’ he said. ‘I thought we should have a … a little talk. Can I pick you up? I mean, it’d be easier to talk to you if you were on my desk …’

‘No,’ said Darktan. ‘And it’d be easier to talk to you if you lay flat on the floor.’ He sighed. He was too tired for games. ‘If you put your hand flat on the floor I’ll stand on it and you can raise it up to the height of the desk,’ he said, ‘but if you try anything nasty I’ll bite your thumb off.’

The mayor lifted him up, with extreme caution. Darktan hopped off into the mass of papers, empty teacups and old pens that covered the battered leather top, and stood looking up at the embarrassed man.

‘Er … do you have to do much paperwork in your job?’ said the mayor.

‘Peaches writes things down,’ said Darktan, bluntly.

‘That’s the little female rat that coughs before she speaks, isn’t it?’ said the mayor.

‘That’s right.’

‘She’s very … definite, isn’t she?’ said the mayor, and now Darktan could see that he was sweating. ‘She’s rather frightening some of the councillors, ha ha.’

‘Ha ha,’ said Darktan.

The mayor looked miserable. He seemed to be searching for something to say. ‘You are, er, settling in well?’ he said.

‘I spent part of last night fighting a dog in a rat pit, and then I think I was stuck in a rat trap for a while,’ said Darktan, in a voice like ice. ‘And then there was a bit of a war. Apart from that, I can’t complain.’

The mayor gave him a worried look. For the first time he could remember, Darktan felt sorry for a human. The stupid-looking kid had been different. The mayor seemed to be as tired as Darktan felt.

‘Look,’ he said, ‘I think it might work, if that’s what you want to ask me.’

The mayor brightened up. ‘You do?’ he said. ‘There’s a lot of arguing.’

‘That’s why I think it might work,’ said Darktan. ‘Men and rats arguing. You’re not poisoning our cheese, and we’re not widdling in your jam. It’s not going to be easy, but it’s a start.’

‘But there’s something I have to know,’ said the mayor.

‘Yes?’

‘You could have poisoned our wells. You could have set fire to our houses. My daughter tells me you are very … advanced. You don’t owe us anything. Why didn’t you?’

‘What for? What would we have done afterwards?’ said Darktan. ‘Gone to another town? Gone through all this again? Would killing you have made anything better for us? Sooner or later we’d have to talk to humans. It might as well be you.’

‘I’m glad you like us!’ said the mayor.

Darktan opened his mouth to say: Like you? No, we just don’t hate you enough. We’re not friends.

But …

There would be no more rat pits. No more traps, no more poisons. True, he was going to have to explain to the Clan what a policeman was, and why rat watchmen might chase rats who broke the new Rules. They weren’t going to like that. They weren’t going to like that at all. Even a rat with the marks of the Bone Rat’s teeth on him was going to have difficulty with that. But as Maurice had said: they’ll do this, you’ll do that. No one will lose very much and everyone will gain a lot. The town will prosper, everyone’s children will grow up, and suddenly, it’ll all be normal.

And everyone likes things to be normal. They don’t like to see normal things changed. It must be worth a try, thought Darktan.

‘Now I want to ask you a question,’ he said. ‘You’ve been the leader for … how long?’

‘Ten years,’ said the mayor.

‘Isn’t it hard?’

‘Oh, yes. Oh, yes. Everyone argues with me all the time,’ said the mayor. ‘Although I must say I’m expecting a little less arguing if all this works. But it’s not an easy job.’

‘It’s ridiculous to have to shout all the time just to get things done,’ said Darktan.

‘That’s right,’ said the mayor.

‘And everyone expects you to decide things,’ said Darktan.

‘True.’

‘The last leader gave me some advice just before he died, and do you know what it was? “Don’t eat the green wobbly bit”!’

‘Good advice?’ said the mayor.

‘Yes,’ said Darktan. ‘But all he had to do was be big and tough and fight all the other rats that wanted to be leader.’

‘It’s a bit like that with the council,’ said the mayor.

‘What?’ said Darktan. ‘You bite them in the neck?’

‘Not yet,’ said the mayor. ‘But it’s a thought, I must say.’

‘It’s just all a lot more complicated than I ever thought it would be!’ said Darktan, bewildered. ‘Because after you’ve learned to shout you have to learn not to!’

‘Right again,’ said the mayor. ‘That’s how it works.’ He put his hand down on the desk, palm up. ‘May I?’ he said.

Darktan stepped aboard, and kept his balance as the mayor carried him over to the window and set him down on the sill.

‘See the river?’ said the mayor. ‘See the houses? See the people in the streets? I have to make it all work. Well, not the river, obviously, that works by itself. And every year it turns out that I haven’t upset enough people for them to choose anyone else as mayor. So I have to do it again. It’s a lot more complicated than I ever thought it would be.’

‘What, for you, too? But you’re a human!’ said Darktan in astonishment.

‘Hah! You think that makes it easier? I thought rats were wild and free!’

‘Hah!’ said Darktan.

They both stared out of the window. Down in the square below they could see Keith and Malicia walking along, deep in conversation.

‘If you like,’ said the mayor, after a while, ‘you could have a little desk here in my office—’

‘I’ll live underground, thank you all the same,’ said Darktan, pulling himself together. ‘Little desks are a bit too Mr Bunnsy.’

The mayor sighed. ‘I suppose so. Er …’ He looked as if he was about to share some guilty secret and, in a way, he was. ‘I did like those books when I was a boy, though. Of course I knew it was all nonsense but, all the same, it was nice to think that—’

‘Yeah, yeah,’ said Darktan. ‘But the rabbit was stupid. Whoever heard of a rabbit talking?’

‘Oh, yes. I never liked the rabbit. It was the minor characters everyone liked. Ratty Rupert and Phil the Pheasant and Olly the Snake—’

‘Oh, come on,’ said Darktan. ‘He had a collar and tie!’

‘Well?’

‘Well, how did it stay on? A snake is tube-shaped!’

‘Do you know, I never thought of it like that,’ said the mayor. ‘Silly, really. He’d wriggle out of it, wouldn’t he?’

‘And waistcoats on rats don’t work.’

‘No?’

‘No,’ said Darktan. ‘I tried it. Tool belts are fine, but not waistcoats. Dangerous Beans got quite upset about that. But I told him, you’ve got to be practical.’

‘It’s just like I always tell my daughter,’ said the man. ‘Stories are just stories. Life is complicated enough as it is. We have to plan for the real world. There’s no room for the fantastic.’

‘Exactly,’ said the rat.

And man and rat talked, as the long light faded into the evening.

A man was painting, very carefully, a little picture underneath the street sign that said ‘River Street’. It was a long way underneath, only just higher than the pavement, and he had to kneel down. He kept referring to a small piece of paper in his hand.

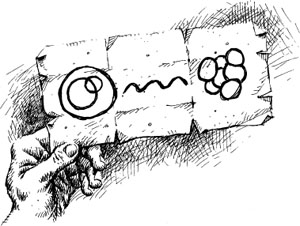

The picture looked like:

Keith laughed.

‘What’s funny?’ said Malicia.

‘It’s in the Rat alphabet,’ said Keith. ‘It says Water+Fast+Stones. The streets have got cobbles on, right? So rats see them as stones. It means River Street.’

‘Both languages on the street signs. Clause 193,’ said Malicia. ‘That’s fast. They only agreed that two hours ago. I suppose that means there will be tiny signs in human language in the rat tunnels?’

‘I hope not,’ said Keith.

‘Why not?’

‘Because rats mostly mark their tunnels by widdling on them.’

He was impressed at the way Malicia’s expression didn’t change a bit. ‘I can see we’re all going to have to make some important mental adjustments,’ she said, thoughtfully. ‘It was odd about Maurice, though, after my father told him there were plenty of kind old ladies in the town that’d be happy to give him a home.’

‘You mean when he said that wouldn’t be any fun, getting it that way?’ said Keith.

‘Yes. Do you know what he meant?’

‘Sort of. He meant he’s Maurice,’ said Keith. ‘I think he had the time of his life, strutting up and down the table ordering everyone around. He even said the rats could keep the money! He said a little voice in his head told him it was really theirs!’

Malicia appeared to think about things for a while, and then said, as if it wasn’t very important really, ‘And, er … you’re staying, yes?’

‘Clause 9, Resident Rat Piper,’ said Keith. ‘I get an official suit that I don’t have to share with anyone, a hat with a feather and a pipe allowance.’

‘That will be … quite satisfactory,’ said Malicia. ‘Er …’

‘Yes?’

‘When I told you that I had two sisters, er, that wasn’t entirely true,’ she said. ‘Er … it wasn’t a lie, of course, but it was just … enhanced a bit.’

‘Yes.’

‘I mean it would be more literally true to say that I have, in fact, no sisters at all.’

‘Ah,’ said Keith.

‘But I have millions of friends, of course,’ Malicia went on. She looked, Keith thought, absolutely miserable.

‘That’s amazing,’ he said. ‘Most people just have a few dozen.’

‘Millions,’ said Malicia. ‘Obviously, there’s always room for another one.’

‘Good,’ said Keith.

‘And, er, there’s Clause 5,’ said Malicia, still looking a bit nervous.

‘Oh, yes,’ said Keith. ‘That one puzzled everyone. “A slap-up tea with cream buns and a medal”, right?’

‘Yes,’ said Malicia. ‘It wouldn’t be properly over, otherwise. Would you, er, join me?’

Keith nodded. He stared around at the town. It seemed a nice place. Just the right size. A man could find a future here …

‘Just one question …’ he said.

‘Yes?’ said Malicia, meekly.

‘How long does it take to become mayor?’

There’s a town in Überwald where, every time the clock shows a quarter of an hour, the rats come out and strike the bells.

And people watch, and cheer, and buy the souvenir hand-gnawed mugs and plates and spoons and clocks and other things which have no use whatsoever other than to be bought and taken home. And they go to the Rat Museum, and they eat RatBurgers (Guaranteed No Rat) and buy Rat Ears that you can wear and buy the books of Rat poetry in Rat language and say ‘how odd’ when they see the streets signs in Rat and marvel at how the whole place seems so clean …

And once a day the town’s Rat Piper, who is rather young, plays his pipes and the rats dance to the music, usually in a conga line. It’s very popular (on special days a little tap-dancing rat organizes vast dancing spectaculars, with hundreds of rats in sequins, and water ballet in the fountains, and elaborate sets).

And there are lectures about the Rat Tax and how the whole system works, and how the rats have a town of their own under the human town, and get free use of the library, and even sometimes send their young rats to the school. And everyone says: How perfect, how well organized, how amazing!

And then most of them go back to their own towns and set their traps and put down their poisons, because some minds you couldn’t change with a hatchet. But a few see the world as a different place.

It’s not perfect, but it works. The thing about stories is that you have to pick the ones that last.

And far downstream a handsome cat, with only a few bare patches still in its fur, jumped off a barge, sauntered along the dock, and entered a large and prosperous town. It spent a few days beating up the local cats and getting the feel of the place and, most of all, in sitting and watching.

Finally, it saw what it wanted. It followed a young lad out of the city. He was carrying a stick over his back, on the end of which was a knotted handkerchief of the kind used by people in story circumstances to carry all their worldly goods. The cat grinned to himself. If you knew their dreams, you could handle people.

The cat followed the boy all the way to the first milestone along the road, where the boy stopped for a rest. And heard:

‘Hey, stupid-looking kid? Wanna be Lord Mayor? Nah, down here, kid …’

Because some stories end, but old stories go on, and you gotta dance to the music if you want to stay ahead.

THE END