CHAPTER 5 Dixie in Literature

Writing to her editor, Harold Latham, Margaret Mitchell recalled how she had once worried that the Macmillan Company “would be stuck with at least 5,000, if not more,” of the first edition of Gone with the Wind. She was now able to laugh about that, she told Latham, especially as the book had sold just more than 1 million copies. What was personally difficult for her, however, was the loss of privacy. Telegrams, special deliveries, and phone calls were a daily nuisance, and a constant stream of visitors came to her home. Even though her fellow Atlantans and local newspapers “begged” people not to bother Mitchell, it was all for naught, and it made her feel like a spectacle. “The out of town visitors and tourists . . . seem to feel that I am like the Dionne quintuplets and should be on view twenty-four hours a day.”1

Peggy Mitchell, as she was known to those closest to her, found herself pleased to be slipping off the best-seller list if it meant less scrutiny of her personal life. “I do not mean that I am unhappy over the marvelous success of the book. That is something I will never get over,” she wrote. “But the public interest in me as a person has been unendurable for some months. I cannot buy a new car or a new hat or pay a fine for improper parking or send a modest wedding present without it getting into the papers.” Gone with the Wind was a publishing phenomenon, and Mitchell’s frustrations about the loss of privacy were very real. The nation, not just the American South, was taken by her epic on the Civil War. The 1,037-page novel exceeded the success of previous novels set in the South. Her epic of the Lost Cause reached an enormous audience—the publisher estimated that 10 million people had read it by 1937—which extended far beyond the borders of the former Confederacy. This was accomplished with the help of a northern publisher, Macmillan, a company that promoted and sold the novel as not only a great story but an authentic portrayal of life in the Civil War South.2

The North had long been the center of publishing, and books about the South and the Civil War, as well as the region’s antebellum past, were a mainstay for publishing houses in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By contrast, as

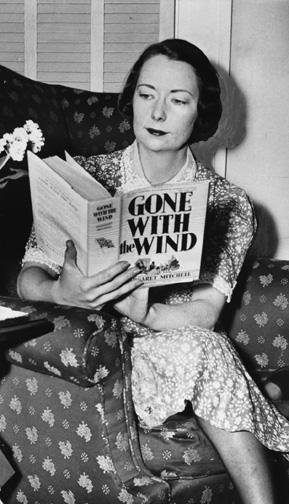

Margaret Mitchell, author of Gone with the Wind, 1936. (Courtesy Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center)

literary critic and historian Archibald Henderson put it, not only was the southern public the “poorest field for national publishing firms” but the region itself was culturally stunted by the “absence of publishing houses or even [an] influential magazine of national significance.”3 There were southern publishing firms, to be sure, but they tended to offer books and novels that justified the South’s role in the Civil War or promoted the concept of southern exceptionalism. Moreover, southern publishers did not have the marketing reach of firms like Macmillan & Company of New York or the J. B. Lippincott Company of Philadelphia. What northern publishers did was to provide the broader American reading public with books about the South on a grander scale, because they had the means to market and distribute books to a larger audience. Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus stories, Thomas Nelson Page’s books about the plantation South, and Thomas Dixon’s enormously successful trilogy on the Ku Klux Klan were printed and marketed by New York publishers. These books appealed to readers across the United States, and their success, as Henderson argued, did not depend on a southern audience. By the time Gone with the Wind came out, in fact, the American reading public was already primed for an epic tale set in the South, because such stories had long been part of their reading diet.

Scholars have written extensively about southern literature and its place in the American literary landscape, as a regional literature that has contributed to southern identity and memory and helped to define the South as a “place.”4 Yet it is significant that literature about the South and the definition of southern identity has often emerged from outside of the region, particularly from the North. Northern publishers marketed the writing of southern authors as authentic portrayals of the region, even when those portrayals included racist caricatures. Northern writers, too, have long held a fascination with Dixie and have helped to define the region for nonsoutherners, profiting handsomely from doing so.

In the period following the Civil War and extending well into the twentieth century, there was an entire genre of travel literature that described the region to the American reading public, whose curiosity about the South provided a niche market for northern publishers. After four years of war, many northerners—veterans, entrepreneurs, wealthy travelers—wanted to see the South for themselves, and they toured the region in droves. Certainly, Americans traveled to other parts of the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century, but, as Cindy Aron points out, the West “remained primarily accessible to those with substantial wealth.”5 Americans fantasized about what could be found on the national landscape, and tourism provided an opportunity to fulfill those fantasies. Moreover, tourism helped people to define “America as a place,” freeing them from their everyday constraints. This was especially true of tourists from the urban-industrial North, who ventured south in search of the nation’s historical and pastoral landscapes.6

Domestic tourism and vacationing increased steadily throughout the nineteenth century, especially by members of the emerging northern middle class, who had the leisure time and the means to travel.7 The South offered a place to unwind from the physical and psychological stresses that accompanied living in cities. Many northern tourists went south for health reasons, to seashores, mountains, and “watering places” (that is, hot and cold springs). Indeed, there were several popular health resorts in the region—from Aiken, South Carolina, to Hot Springs, Arkansas. Many believed disease could be prevented or cured at these places. Natural springs remained popular through the 1880s, but by the end of the century there was a movement toward visiting “natural wonders, historic places, and the numerous cultural attractions of cities.”8 Improved and additional rail lines, as well as the advent of steamships, meant increased travel to the region. The South was a cultural commodity, and travel literature helped to sell it as such.9

Northern tourists came to the South in part because they were, as historian Tom Selwyn argues, “chasing myths” about the American past. Tourist destinations tend to have their own “spirit of place,” and local people, especially in rural settings, serve as representatives of this “imagined world,” which is both premodern and preindustrial. For northern travelers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the South was that imagined world. In Dixie, they went in search of pastoral America and convinced themselves that when they traveled south they had exchanged the modern for the authentic.10

Throughout the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, journalists and travel writers published their views of the region in widely read magazines like Century, Scribner’s Monthly, and Harper’s Weekly, and northern firms published books giving the American traveling public firsthand accounts of the region and its people. This literature helped define the region and encouraged northern tourism to the South. And for southern entrepreneurs who sought to capitalize on the tourist market, northern travel literature helped them determine and develop the types of attractions that northern tourists hoped to see when they ventured below the Mason-Dixon Line.

In some ways, all types of literature about the South between the Civil War and World War II can be regarded as travel literature. Joel Chandler Harris’s stories of Uncle Remus not only offered readers descriptions of the Old South and what was commonly referred to as the “old-time southern negro” but also enticed travelers from the North and Midwest to visit the South in the hope of seeing a southern plantation and people like Uncle Remus. Margaret Mitchell’s complaints about visitors and tourists coming to her door in Atlanta also offer evidence that Gone with the Wind, published fifty-six years later, was more than a successful novel. It was a powerful piece of travel literature, which drew thousands of people to her hometown and to the state of Georgia.

Northern tourism to Dixie was certainly not a new phenomenon in the late nineteenth century; thousands of northerners traveled south prior to the Civil War. Historian Eric Plaag has argued in his research on northern travelers to the South in the antebellum period that the northern press was responsible for the creation of the national narrative about the region in the period leading up to the war—a narrative that attracted wealthy tourists to Dixie. That trend continued in the war’s aftermath. The southern press did not wield such influence nationally, and though the Lost Cause narrative took hold in the former Confederacy soon after defeat, it did not have the same traction in the North. Thus, the national narrative of the South in American culture continued to be defined by nonsoutherners, specifically by the northern press.11

Nineteenth-century tourists, most of whom were well-to-do and had the leisure to spend anywhere from a few days to a few months traveling, had to look no further than popular magazines to learn more about the South. Articles describing life in the region after the Civil War appeared with frequency in northern magazines. In 1874, for example, Scribner’s Monthly offered its readers an entire series on the former Confederacy. Journalist Edward King and artist J. Wells Champney wrote and illustrated the articles, all of which were eventually published as The Great South (1874). The record of their journey is almost 800 pages and covers the expanse of the former Confederacy from Texas and Louisiana in the west to Florida and Maryland along the East Coast. King’s travels took him to rice plantations in South Carolina and cotton plantations in Mississippi and from the French Quarter of New Orleans to the summit of North Carolina’s Mount Mitchell. Along the way, he spoke with various southerners, whom he placed in different categories of the “southern type”—for example, the planter, the Negro, and the poor white. Champney provided illustrations of each. King also observed what he regarded as the failure of Reconstruction in Georgia and of “negroes in absolute power” in South Carolina.12

Throughout, King’s observations provide a relatively impartial examination of the South, though he is not immune to stereotypical references. For example, he offers a poignant and sympathetic description of black field hands on a Louisiana plantation, who, because they were illiterate, had no choice but to go to the plantation owner with hat in hand to request that he read the letters they received. Later, King links the adjective “lazy” to “negro” in describing some black workers and writes with some surprise about an “intelligent-looking” black woman. Yet The Great South in its entirety offered a realistic portrait of the region in the years prior to sectional reconciliation.13

Philadelphia publisher J. B. Lippincott followed, in 1876, with the book Florida: Its Scenery, Climate and History, a volume that provided descriptions of Charleston and Aiken, South Carolina, as well as Augusta and Savannah, Georgia. Sidney Lanier, best known for his poetry and literary criticism, was the author. Although he was a Georgia native, Lanier’s descriptions of the South helped define what northerners could expect from the region. Like most nineteenth-century tourist accounts, the book focused on the landscape, health benefits of the region, flora and fauna, commerce and agriculture, and escape from northern winters. In Aiken, for example, “a considerable number of persons from the North [found] the climate so grateful” that they bought land and built homes, only to have to think about “those unhappy persons whom one has left in the Northern winter.” Charleston offered its visitors “genial old-time dignity,” and Savannah was awash in its “lavish adornment of grasses, flowers and magnificent trees” hung with Spanish moss. In a section on resort towns, Lanier emphasized the health benefits of the South in towns where even those tourists who were not sick sought “to flee from the rigors of the northern climate.”14

Books about the South did not simply make for good reading. They were also useful to northern travelers headed to Dixie. In fact, one of the preconditions for significant tourism to occur, according to historian Patricia Mooney-Melvin, is that enough information exists “to excite the imagination and encourage people to leave home for sites unknown.” Another is that there be a sufficient number of people with the disposable income and the leisure time needed to travel.15 In the immediate post–Civil War era, mostly only wealthy northern industrialists could afford to travel. But, as the century wore on, tourism in the United States became more affordable and a mass phenomenon. This trend continued in the twentieth century with the mass production of automobiles, beginning in 1908 with Henry Ford’s Model T, which forever changed tourism and who could tour. Thus, books about the South—whether fiction or travel literature—served an important function in promoting tourism to the former Confederacy.

Florida was considered the most exotic of southern landscapes and often the destination of many northern tourists, especially the wealthy, who early on wintered at the lavish hotels of St. Augustine, later abandoning them, in the early twentieth century, for the newly created resort of Miami. “We are soon en route for Florida,” one northern tourist exclaimed, “which is the kind of Mecca of our hearts’ desires. Florida! The very name is suggestive of sunshine and flowers, orange groves, and the sweet-scented air of ‘Araby the blest.’”16 Still, there were many destinations for northern tourists to explore along the way to Florida, and their descriptions offer insight into how they defined the South for the American traveling public.

In the years following Reconstruction, both northern and European travel writers explored the South, largely in an effort to describe how the region was recovering from four years of civil war. Richmond received considerable attention by travel writers in the 1880s. Virginia was the first state northern tourists saw of the South, and Richmond seemed to be particularly southern, as the former capital of the Confederacy. The city was a place of economic revival but one that was still battle worn. Scribner’s Monthly described Richmond’s rebound from the war as seen through its tobacco and iron industries, and Matthew Arnold described the “rather ragged streets of Richmond . . . which suffered terribly in the war.”17

More often, however, travel writers were struck by the differences between North and South. C. B. Berry, writing for New York publisher E. P. Dutton, described the South as “more homelike than farther north, if less luxurious.” For Berry, the hotels seemed quainter than those in the North, as they had fireplaces instead of steam pipes to heat the rooms. Lady Duffus Hardy, who toured the South in 1883, was more enamored with the southern people—white and black. Her observations, although insightful about white southerners, were racist when depicting African Americans. “It is at Richmond we get our first view of the South and the Southern people. Although we are only twelve hours from the booming, bustling city of New York . . . we feel we have entered a strange land,” Hardy wrote of Virginia. In this strange land, she swiftly sensed the spirit of the Lost Cause, noting that “it impregnates the very air we breathe.” In essence, Richmond’s whites lived as though “it is ever yesterday.” Richmond’s blacks, like other southern blacks described by travel writers, come across as exotic and pathetic creatures in Hardy’s account. The group of black men she saw whittling sticks while sitting on a fence were to her a “gathering of black crows,” and she likened them to “lazy cattle basking in the sunshine in supreme idleness.” As offensive as these comments are to the modern reader, it was these types of observations that furthered the idea of an exotic South and attracted tourists to the region.18

Lady Hardy’s fellow Englishman, Matthew Arnold, toured the United States two years later, and he, too, visited Richmond. In his letters to his sister back in England, Arnold’s observations were reminiscent of Hardy’s. He remarked on the vivid reminders of suffering caused by the Civil War and made a point to visit Hollywood Cemetery. Like Hardy, he wrote with curiosity about seeing “coloured children” and referred to them as “dem little things.” Before leaving Richmond, he remarked wistfully, “If I ever come back to America, it will be to see more of the South.”19

New York native and Anglophile Henry James saw little that was different in “melancholy Richmond” when he visited the city in 1907 and described it as “simply blank and void.” He was pointed in his criticism of the institution of slavery, calling it the “absurdity [that] had once flourished there.” The “old Southerners” of the Confederate generation were nothing more than “pathetic victims of fate.” Yet James’s criticisms of the city no doubt contributed to the romantic image of the Confederacy, a tragic romance to be sure. On his tour of Richmond, James visited what had quickly become an important tourist destination in the city—the Confederate Museum, founded in 1896 by the women of the Confederate Memorial and Literary Society. In describing his tour of the museum, he referred to it as an exhibit of “sorry objects” that told of a “heritage of woe and glory” and yet found that the old woman who greeted him at the museum embodied a certain southern charm. Clearly taken by her southern accent and fine manners, James wrote, “No little old lady of the North could, for the high tone and the right manner, have touched her.” His descriptions, even his critiques, likely aroused northerners’ curiosity and contributed to the increasing number of tourists that traveled to Virginia and the rest of the South.20

Southern writers, too, helped to shape an image of the South for popular consumption. Thomas Nelson Page and Thomas Dixon, for example, wrote novels that revived a mythological South. Dixon was successful, in fact, in helping the nation reconstruct its views about race and the region’s “Negro problem.” Page’s books were also profitable releases. In Ole Virginia (1887) and Social Life in Old Virginia (1897), both published and marketed by New York’s Charles Scribner’s Sons, offered readers an idyllic image of the plantation South. Dixon, a popular evangelist in Boston and New York well before Doubleday Press published The Leopard’s Spots (1902), was already considered by northerners and the northern press to be an expert on all things southern prior to the release of his Reconstruction trilogy, which assured its success in the marketplace. Even though Dixon’s work was intended to highlight the perceived threat of black men, which northern and southern whites shared, what his writing made clear was that the South had control of its “Negro problem” and thus was a safe place for the northern tourist to observe the black man in his exotic and “natural” environment.21

Savannah was a frequent stop for tourists on their way to Florida. As early as 1874, Sidney Lanier noted that the city was “much frequented by Northern and Western people during the winter and spring.”22 Bonaventure Cemetery was already a tourist attraction, as was Forsyth Park. In 1878, Philadelphia publisher J. B. Lippincott produced Georgia: A Guide to Its Cities, Towns, Scenery, and Resources, which claimed that Savannah was “well calculated to charm the stranger” and that it had become a favorite destination for northern tourists because it offered them the chance to “retreat from the din and confusion of larger and more bustling cities.”23 Indeed, escaping the modern city for one that was less congested was one of the appeals for tourists traveling south.

Lady Duffus Hardy, who was struck by the way in which Richmond lived and breathed its Confederate past, liked Savannah well enough but found “little architectural beauty in the city or its surroundings.” And although she complained that Forsyth Park was so diminutive that it would fit into a small corner of Kensington Gardens, it was balanced by the “warm southern breeze, and the oleander, orange, lemon, and magnolia.”24 The Reverend Timothy Harley, who toured Savannah a few years later, in 1886, sought to describe the city’s residents, whom he found to be representative of the heterogeneous nature of the United States. Harley noted that northerners had adopted the city as home for purposes of trade and observed that “the Hebrews are a numerous and wealthy class of residents.” He did not observe African Americans as exotic creatures; rather, he offered insight on the city’s race relations, commenting that “the coloured people are not treated there [Savannah] as equals.” Significantly, he noted that neither were they treated as such in the North.25

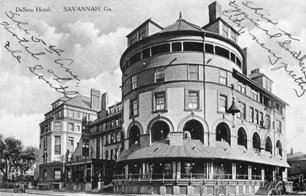

Postcard of the Hotel DeSoto, 1911. The hotel was a favorite of northern tourists, described by one as “the 5th Avenue hotel of the South.” (Author’s collection)

Tourists traveling from the North and Midwest found Savannah particularly southern—for its landscape and for its tourist attractions. Northern travelers admired the city’s Spanish moss and regarded it as “the mainstay of the Southern landscape.”26 Even more interesting to northern travelers was the opportunity to visit and see in person a true southern plantation—the Hermitage—and its former slave quarters. John Martin Hammond, a travel writer from Germantown, Pennsylvania, referred to the Hermitage as a place that survived as an example of life “befo’ da wa.’” The slave quarters had a “picturesque quality,” although they appeared to him to be “more like habitations for pigs than for human beings of any color or condition of servitude.”27

The Hotel DeSoto, which catered to northern tourists, billed itself and Savannah as a “natural resting place” for the traveler headed to the “extreme South” (that is, Florida). For the 1896–97 tourist season, the DeSoto published a brochure designed for the northern tourist, which emphasized the city’s “enticing scenery and balmy climate.” The brochure also included photographs of the slave quarters of the Hermitage plantation, as well as of a “negro cabin on Bonaventure Drive.” The cabin was a dilapidated wooden structure chinked with mud, and a black woman and her children were pictured sitting at the front door. Including photographs of such a cabin or the slave quarters of a plantation in a brochure to attract northern travelers indicates that the proprietors knew that this particular group of tourists had expressed an interest in seeing images of the “Old South.”28

Southern literature and travel accounts changed markedly in the second half of the nineteenth century, especially after the publication of Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus stories. Certainly, Harris did not invent the style of writing in black dialect—it had long been a part of American literature. However, Harris’s influence was pervasive and long lasting. He was respected by contemporary folklorists and inspired other writers to incorporate dialect, among them Mark Twain, but also lesser-known writers, who employed black dialect with much less success. Moreover, although ethnic dialects were often used as a device to portray other non–Anglo-Saxon people, especially German and Irish, the use of black dialect in portraying African Americans was the most common use of a non–Anglo-Saxon dialect.29

Harris’s folktales were a phenomenal success, attracting an international audience. The stories were highly regarded by folklorists for their dialect, and they appealed to adults and children alike. Moreover, one cannot underestimate the impact of Harris’s stories on the South’s tourist industry. There is no doubt that readers in the North and Midwest—the two regions that produced the greatest number of tourists for the South in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—were fans of the stories. In 1917, a travel writer who defined herself as a “true provincial New Yorker” described her impending trip to the South as going to “a place of sun, chivalry, romance and Uncle Remus.”30 What was it about these folktales that entertained readers and then motivated them to visit the region?31

Joel Chandler Harris re-created scenes from an antebellum southern plantation, and, although the stories were set in the post-Reconstruction South, his purpose was to open for readers a window onto the world of the “old-time negro” who had lived under slavery. Harris originally wrote the tales for publication in the Atlanta Constitution, and they were eventually published by New York’s D. Appleton & Company. As Harris wrote in his introduction to Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings (1880), “I have endeavored to give to the whole a genuine flavor of the old plantation.”

Title page from Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings, 1881. (Courtesy Special Collections, J. Murrey Atkins Library, University of North Carolina at Charlotte)

He also intended his stories to serve as a counterpoint to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Stowe, in his estimation, “attacked the possibilities of slavery,” but Uncle Remus portrayed former slaves who had lived under the system and who, according to Harris, had “nothing but pleasant memories of the discipline of slavery.”32

Harris’s use of dialect gave the stories a perceived authenticity, and, in the wake of Uncle Remus’s success, the use of dialect appeared with even greater frequency in articles, essays, novels, and travel accounts in which the South was the setting. That success had as much to do with the political and social landscape as it did with Harris’s talent for writing. Following the war, African Americans became players on the national stage of politics, challenging the Anglo-Saxon status quo. Immigration from southern and eastern Europe steadily increased throughout the nineteenth century and contributed to the size and diversity of America’s cities. Thus, Harris’s stories, like those of Thomas Nelson Page and others, offered readers a retreat from the anxiety of all that change by focusing on a time and place—the plantation South—where life was simpler and the “race question” was not a question at all.

Against this backdrop, scientists pursued Darwin’s theory of “survival of the fittest,” and white men, North and South, became brothers in the cult of white supremacy that emerged in the late nineteenth century. This Anglo-Saxon brotherhood was buoyed, in part, by sectional reconciliation—a reconciliation that celebrated white manhood while ignoring the most significant outcome of the Civil War—emancipation. In the South, moreover, the social and political backdrop to the bucolic imagery of plantation literature was an increasingly violent racism. Lynching escalated dramatically in the 1890s and was soon accompanied by race riots. Yet, through the culture of reconciliation, in which Confederate veterans were redefined as patriots, northerners turned a blind eye to that violence and left white southerners to their own devices to deal with “the Negro.” Veterans’ reunions were organized, and wealthy northerners spent their money touring the South to see the plantations described by Page and Harris and to meet any number of southern “types,” but most especially the happy-go-lucky blacks of literature.33

Southern authors undeniably contributed to this bucolic image of the South, which northerners bought into, but they were not alone. Northern travel writers complemented those works by describing the southern landscape and its people in a way that perpetuated stereotypes. Significantly, the northern publishing industry was most responsible for carrying out the construction of southern identity for American audiences. D. Appleton, of New York, sold and marketed the tales of Uncle Remus; and Charles Scribner’s Sons sold and marketed the stories of Thomas Nelson Page, including The Negro: The Southerners’ Problem. Without the support of the northern publishing industry, the circulation of these stories would have been severely limited.

What did the travel literature to the South say about the region? What was it that northerners and midwesterners hoped to see and experience while below the Mason-Dixon Line? In part, what attracted northerners were the differences between the two regions—urban versus rural, industrial versus agricultural, modern versus antimodern. During the late nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, the reasons for traveling south were clear. Cold northern temperatures were certainly a motivation. Rapid industrialization and urbanization, as well as immigration from southern and eastern Europe, produced feelings of anxiety among residents in northern cities and motivated people to travel to the South, where they might experience a preindustrial America. It was the same reason tourists traveled to the West. But the rural South, with its ties to the agricultural past, its slower pace of life, and its pliant servant class, was more easily reached from the East. The South offered northern tourists the antithesis of modernity, and the region served as the embodiment of the nation’s rural ideals well into the twentieth century.34

The South remained largely agricultural in the early twentieth century, except for some cities like Richmond and Atlanta, and visitors remarked on those differences in their travel accounts. “Everything is done with leisurely dignity and quietude in the South; there is no bustle or confusion, no general rush, even at the [train] depots,” noted Lady Duffus Hardy in 1883. Near the end of the century, Julian Ralph, a native New Yorker and longtime journalist for the New York Sun, offered a similar description in his book Dixie; or Southern Scenes and Sketches. Speaking of the South, Ralph wrote, “I could cast my lines off from the general world of today and float back into a past era, there to loaf away a week of utter rest.” He contrasted the urban-industrial North and Dixie by explaining that in the South he could while away the hours, “undisturbed by telegraph or telephone, a hotel elevator or clanging cable car, surrounded by comfort . . . and at liberty to forget the rush and bustle of that raging monster which the French call the fin de siècle.”35 New Yorker Mildred Cram, who in 1939 achieved fame for her screenplay Love Affair, later remade as An Affair to Remember (1957), noted these differences in her trip to seaport towns in 1917. “Charleston is perhaps the only city in America that has slammed its front door in Progress’s face and resisted the modern with fiery determination,” she wrote.36

Much of what made travelers to the South feel at ease was its rural landscapes, although it was not without its critics. Henry James caustically remarked that in the South “illiteracy seemed to hover in the air like a queer smell.”37 Most writers were much more generous than Henry James, and they tended to see a South he clearly was not looking for. John Henry Hammond traveled to and wrote about the South that intrigued many northern travelers, in Winter Journeys in the South (1916). “The ‘Old South’ has been clearly defined by sentimental historians and in works of popular fiction,” Hammond wrote. “According to this definition,” he continued, “the ‘Old South’ is a place of perpetual sunshine, large blooming, fresh-hued flowers, a balmy atmosphere, gardens, quaint walks hedges, big white houses embowered, and leisurely men.”38 Although Hammond appeared to acknowledge that the South was an imagined place, he still claimed to have found, in Camden, South Carolina, “more of the atmosphere of the ‘Old South’ than in any other place in the Southern States.”39

The South was often described as “romantic,” and what made it romantic was its landscape and, very often, the region’s history. During the nineteenth century, Americans were motivated to tour by their need to define America as a place, and, although tourists were attracted to a picturesque countryside, historic sites ranked high on their list of places to visit. Moreover, northern tourists sought to experience a way of life that was no longer contemporary. This proved to be especially true in the South, where, as historian Rebecca McIntyre has argued, the “old world landscape [of] crumbling plantations . . . turned southern losses into tourist attractions.”40

Since the early nineteenth century, plantation literature had drawn on descriptions of the region as a place where visitors could expect “romance, hospitality, and beauty.”41 This romantic image of the South in literature remained constant well into the twentieth century, as northern tourists sought to come face-to-face with antebellum mansions, where they might imagine chivalrous planters, beautiful belles, and faithful Negroes.42 New Yorker Mildred Cram’s descriptions of the Hermitage, a Savannah plantation frequented by northern tourists, provide evidence of how fiction about the South influenced her thinking. “The Hermitage seemed to us the realisation of a literary dream,” she mused. “[It] satisfied our longings, stirred up memories of dreams we had ever dreamed of the South, [and] filled us with satisfactions,” she continued, “as if the chimera we had been pursuing all the way from New York were captured at last. . . . It was all that a plantation should be.”43

A black driver, whom Cram referred to as her “chocolate chauffeur,” took her to see the Hermitage. What she did not seem to recognize was that the driver, as well as a former slave she met while at the Hermitage, understood their role in the tourist trade that came through Savannah and played it up for economic benefit. The driver, who was paid, took Cram to the old plantation, where he stopped and called out for a woman named Molly. “Who is she?” Cram asked. As he lit a cigarette, the driver responded, “She was a slave,” and then turned to Molly and said, “Molly, tell us about the ole times—befo’ the wah.” At first, Molly feigned illness, but then the driver said she always gave that response. Then he told Cram, “Give her a qua’tah and she’ll find her tongue.” Later, a group of young children came running over and shouted that they would dance for ten cents. Thus, the driver, the former slave with her stories of life on the plantation before the Civil War, and the children willing to dance for white people all provide evidence that African Americans, too, were keenly aware of being part of the South’s exotic tourist trade and used it to support themselves.44

Significantly, the driver wanted Mildred and her husband to also see the progress of his race and took them to see the homes and community that African Americans had created since the end of slavery. As she described it, “He wanted us to see what freedom and ambition had done for him and others like him.” Frame houses, women in white shoes, and children in sailor suits were a source of pride. The Crams were initially disappointed with this part of the tour, since it was the “martyrdom of his race” that had struck their imagination. “We had been demanding an eternal raggedness and poverty and picturesque ignorance for our own purely aesthetic enjoyment,” she admitted. And, indeed, she was not alone, as other northern travelers were in search of a similar experience.45

In addition to the romance of the South, northern travel writers seemed fascinated by southern blacks, and northern tourists expected them to be part of their southern tour. To that end, publishers like J. B. Lippincott offered readers what had long been a staple of literature about the South—descriptions of the “southern Negro.” From the “darkies” in South Carolina to the Florida Negro who had a “primitive” ear for music, southern blacks increasingly became stock characters in the travel literature of the South because they appeared markedly different from African Americans living in the North; southern blacks behaved more like the servant class that northerners expected them to be. Indeed, they were often described in terms of their labor and work habits, with the accompanying statement that the South “knows the Negro” and how best to supervise him.46

“Cotton Picking in the South,” postcard, 1930s. Northern travelers frequently commented on their desire to see blacks working in the cotton fields. (Author’s collection)

Post–Civil War travelers of the nineteenth century wrote about seeing blacks on southern plantations, and this trend continued into the twentieth century, even though southern blacks were now generations removed from the plantation. New Yorker Mildred Cram, who had expectations of being in the land of “Uncle Remus,” went so far as to proffer observations of southern blacks on a state-by-state basis as she visited the seaports of the South. “It seemed to us that the negroes were shabbiest in Baltimore and Charleston, that they were most likeable in Norfolk, that they were most offensive in Savannah and most picturesque in New Orleans and St. Augustine,” Cram wrote. “The upstart type [in the North] has crept further and further into the South to the great disadvantage of the self-respecting, infinitely better class that has not forgotten how to say ‘Yessah’ and ‘Yes’m.’” As if she were an authority on southern race relations, Cram further remarked that she “[knew] that the jaunty, overdressed, impudent and self-assertive negro cannot possibly be the result of paternal [that is, white] authority.”47

In a 1921 article for Century magazine, entitled “Quaint Old Richmond,” Mary Newton Stanard described the city as one in which the Old South could still be seen in the New. What she found “quaint” were members of Richmond’s black community. She found the “negro janitor” of Virginia’s Medical College to be “one of the most picturesque characters in Richmond.” She told readers that should the tourist “hear the singing of the negro ‘stemmers’ [from the tobacco factories], men and women, boys and girls, he might well wonder if he is not approaching a plantation instead of a factory.” Black women street vendors appeared equally exotic to Stanard, who described their “ebon skins and snow-white sparkling teeth,” as well as how they would “croon old melodies as they shell black-eyed peas or make up nosegays that charm coin from the most canny of purses.” The cover illustration for this article included a slave cabin superimposed on the front lawn of the Confederate Women’s Home.48

Even children’s literature about travel to the South included romantic descriptions of the region as well as caricatures of southern blacks. An excellent example comes from the series Bunny Brown and His Sister Sue. The Stratemeyer Syndicate, formed by New Jersey native Edward Stratemeyer, published the series. The syndicate was also responsible for such famous series as the Bobbsey Twins, Nancy Drew, and the Hardy Boys. In 1921, the syndicate published Bunny Brown and His Sister Sue in the Sunny South by Laura Lee Hope—a pseudonym for any number of authors who wrote for the Stratemeyers, including Stratemeyer himself.49 The premise of the story is that Bunny Brown’s father has business to do in Florida and takes the entire family on his trip to the South; as they travel, the characters comment on the landscape and the southerners they meet.

Throughout the story, Mrs. Brown communicates her desire—and the desire of many northern tourists to the South—to see a cotton plantation and blacks working in the fields. Even before the trip commences, she asks her husband if she will be able to see cotton growing, adding, “I have always wanted to see a cotton field with the darkies singing and picking the white, fluffy stuff.”50 The Brown family does visit a cotton plantation in Georgia, and there Bunny Brown and his sister Sue meet the children of the plantation owner. They go out into the fields, where “they could hear darkies singing.” Upon hearing them sing, Bunny exclaims, “It’s jolly!” The planter’s son Sam concurs: “Yes, the darkies always seem to be happy.”51

Later, they witness black men, women, and children dancing to the music of a banjo, perpetuating the myth of a happy-go-lucky race. The use of black dialect is employed to establish southern blacks as exotic and

Cover for Laura Lee Hope’s Bunny Brown and His Sister Sue in the Sunny South, 1921. (Author’s collection)

simple. “Golly dat suah mek me want to shuffle mah feet!” proclaims one black character, while the other chimes in: “Why doan you shuffle ’em den, Rastus? . . . Show de white folks how you kin cut de pigeon wing!”52 Here the author uses the name Rastus, commonly used as a name for black servants. Moreover, southern blacks who speak in dialect and dance for “white folks” serve as entertainment—not only through literature, but through children’s literature at that. Indeed, the thousands of northern tourists who ventured south traveled in the hope that they, too, might see blacks working, singing, and dancing for their benefit.53

Many authors writing about the South sought to emulate Joel Chandler Harris and attempted to write dialect for southern black characters—generally not to good effect. Travel writers and journalists used dialect, as did novelists, for local color. To black intellectuals, the use of dialect had a detrimental impact on the African American community. Sterling Brown, longtime professor at Howard University, said as much in an article entitled “Negro Character as Seen by White Authors.” Brown listed seven different stereotypes in literature perpetuated by white authors—many of which were southern, but certainly not all. “Authors are too anxious to have it said ‘Here is the Negro,’ rather than here are a few Negroes whom I have seen,” he argued. Of the several stereotypes he identified, the two most frequently used in travel accounts and popular literature were the Contented Slave and the Local Color Negro. The contented slave was the stereotype that appeared in the sentimental literature of Thomas Nelson Page. Like Harris, Page was a local colorist because he employed dialect. Even writers who were not southern, as in the case of Edward Stratemeyer, used dialect as local color, which Brown argued “stresses the quaint, the odd, the picturesque, the different.”54

Earl Conrad, a white author who wrote reams of material on race relations in the United States and who was a critic of Jim Crow, concurred with Brown in his assessment of the use of dialect. Conrad, as had Brown before him, even referred to southern writers of dialect as “neo-Confederates.” Not only did they use dialect to infer inferiority, Conrad argued, but “the neo-Confederate writer Jim Crows the Negro in his writing” and tries to maintain the status quo through speech. He accused Margaret Mitchell of being one of the worst offenders, because she employed black dialect but never used any nuances of language to illustrate a white southern drawl. Conrad found that northern writers were no better in their use of dialect. They, too, used words like “nigger” and “pickaninny” to describe southern blacks, “in the name of realism.” The result, according to Conrad, was that Negro dialect gave to blacks the “onus of inferiority.”55 Such valid criticism did not deter northern magazines or publishers from publishing books whose descriptions of the South were distinguished by their use of Negro dialect well into the 1930s.

By the mid-1920s, the genre of travel literature based on automobile travel by the upper classes had gone out of fashion. Middle-class Americans could afford their own cars and preferred to experience “motoring” for themselves. Rather than read travel accounts, the American reading public’s interest in the South was piqued by the work of novelists. The antebellum South continued to serve as a popular setting for both fiction and plays, which helped to perpetuate the “moonlight-and-magnolias” image of the region. Although not travel literature, per se, these books were important to perpetuating the fantasies that northern travelers had about the South and continued to draw them to the region. Indeed, as Stephanie Yuhl has shown, southern writers, like those in Charleston, South Carolina, “cultivated relationships with New York publishers,” which in turn were useful in promoting tourism to the region, even if this was not the authors’ intent.56

DuBose Heyward’s Porgy (1924) and Stark Young’s So Red the Rose (1934) were not simply successful novels—they were also instrumental in drawing tourists to Charleston, South Carolina, and to Natchez, Mississippi, respectively. Heyward’s story of southern blacks on Catfish Row, although considered racially progressive for its time, still appealed to nonsoutherners’ fascination with the exotic South. Similarly, Young’s portrayal of the Civil War South through the lens of the Portobello plantation was a publishing success, before Gone with the Wind eclipsed it in sales and popularity. Nonetheless, Young’s novel was made into a film and no doubt contributed to the success of the Natchez Pilgrimage, which, during the 1930s, attracted thousands of tourists to Mississippi to see its antebellum mansions.57

The Southern Literary Renaissance that emerged in the 1920s and 1930s certainly offered a new and even critical perspective on the region by native southerners, and their poetry and fiction represented a departure from the romance of the Lost Cause.58 Enter Margaret Mitchell, whose historical and romantic epic about the Old South and the Civil War refocused the nation’s attention on the “moonlight-and-magnolias” South. Significantly, Gone with the Wind was sought out by the most successful New York publishing firm of its day—Macmillan. Lois Cole, an associate editor for Macmillan in its Atlanta office, was aware that Mitchell had long been at work on a novel about the Civil War. Yet it was Harold Latham, Macmillan’s editor in chief, who convinced Mitchell to submit her manuscript. It is an oft-told story that Latham came to Atlanta in 1935 in search of southern authors and met Mitchell, who at their first meeting claimed she did not have a manuscript. Yet Latham’s persistence paid off, when Mitchell showed up at his hotel before he left town and gave him the manuscript of what would become Gone with the Wind. According to Latham, the “pile of sheets reached to her shoulders,” and he had to buy an extra suitcase to carry it back to New York.59

Margaret Mitchell was grateful to Harold Latham not only for her personal success but for pursuing the work of other southern authors. Writing in 1938, she told Latham, “You have done so very much for writing people here in the South.” It was not simply that he had published her manuscript, she told Latham. “For so long people in the South believed that a Southern writer did not have a chance without pull,” she wrote, adding that “now they know differently and it’s due to you.”60 These sentiments were confirmed in Mitchell’s correspondence with Thomas Palmer, president of the New York Southern Society—a group of southerners living in New York City. “As you know,” she wrote Palmer, “the South is not always fortunate in her visitors from other places. Many strangers come to our section with remarkable misconceptions about the South and Southerners. . . . When they go away they spread erroneous stories about us.” Mitchell’s reference to “strangers” and “erroneous stories” was a common complaint among southerners, who felt that since the Civil War northerners had defined the South for the nation’s readers—and poorly, at that. Latham, she assured Palmer, was different. He was in “sympathy” with the South, and she was impressed that “the editor of a great publishing house like The Macmillan Company [took] the trouble to come South twice a year hunting for manuscripts by new authors!”61

Gone with the Wind, more than any other novel of the early twentieth century, did much to encourage tourists from the North and Midwest to venture south, although the book had its detractors. A reader from Oak Park, Illinois, wrote Macmillan that much of what was to be found between the covers of the book was “coarse, vulgar, revolting and obnoxious to decency and refinement.” Another writer from East Pembroke, New York, concurred, saying that “it can only cause disgust and condemnation and a source of shame to both author and publisher.” The letter was signed “Yours for cleaner literature.”62 Even John Marsh, Mitchell’s husband, warned Macmillan that, because his wife had portrayed the South “with considerable frankness” and with a “heroine [who] is a hellion,” he might expect trouble from the United Daughters of the Confederacy. “The UDC ladies are a force to be reckoned with in these parts,” Marsh wrote. “If they should take out after Peggy, you wouldn’t have to worry about getting publicity, but it might not all be the kind you want.”63

African American journalists, undeniably, had different issues with Mitchell’s novel, especially after it won the Pulitzer Prize for literature. Frank Marshall Davis, in an editorial for the Kansas City Plaindealer, was incensed that the Pulitzer committee gave a prize to an author who “went out of her way to support the institution of human slavery [and] praise the Uncle Toms of that period.” Elizabeth Lawson, writing for the Cleveland Gazette, also condemned giving the award “to a novel which chooses Klansmen for its heroes, which describes its ‘Negro’ characters as ‘drunken black bucks’ and ‘monkeys out of the jungle’ [and] whose climax is the attempted rape of a heroine by a ‘black ape.’” As she saw it, Margaret Mitchell had done nothing more than to follow in the “rotten” footsteps of “Dixon’s odoriferous novel,” The Leopard’s Spots.64

Critics of Gone with the Wind, however, were certainly outnumbered by the millions who loved it. The book became a best-selling novel and arguably one of the best pieces of promotional literature the South could have ever imagined. According to a review in the New Yorker magazine, the book was a “masterpiece of pure escapism.”65 In fact, northern tourists, most of whom had read the book, traveled in search of the Old South of Mitchell’s imagination, in the hope of seeing plantations, southern belles in hoopskirts, contented and loyal blacks, and romantic landscapes. Mitchell had provided readers with a modern tale set in a premodern world. Constance Lindsay Skinner, a critic and writer from Canada, wrote as much to Lois Cole, Macmillan’s associate editor: “It is so very modern—and yet it is set in the most romantic period of America’s past.”66

Harold Latham once told Margaret Mitchell that she could expect “half the population of North America” to camp at her doorstep, a prospect Mitchell laughed at. She later wrote to Latham to apologize and to ask how long “all this” (the tourists coming to her home) would last. “For months I have been aroused every morning at five by telegrams and special deliverys [sic] and long distance phone calls,” she complained, and “there are usually visitors sitting in our living room waiting for us to get through our meals.” Mitchell learned that several “Taras” had emerged in Clayton County, Georgia, to satisfy the curiosity of northern tourists. The county served as the setting for her novel, but, as Mitchell was quick to tell anyone, Tara was not a real place. She also discovered that in Atlanta a sightseeing bus was taking out-of-town visitors on a tour that “pointed out the store where Frank Kennedy got his start, the site of Scarlett’s Victorian home, Miss Pitty Pat’s house, et cetera,” even though there were “monthly statements in the newspapers that no such places ever existed except in my mind.” Mitchell told her husband that she thought of taking the tour, and, when a site was pointed out as being from the novel, she would take the “megaphone in [her] hand and shout, ‘That’s a lie!’” He replied that the tourists would probably pay her a salary to do so on a regular basis.67 In a 1941 interview, Mitchell commented that the tourist invasion of her life in Atlanta had calmed down to the point where “the sightseeing bus now only comes to the corner of the block and children get out and pull up some shrubbery and leaves of one of my neighbors.” She added, “I live in an apartment and it isn’t my shrubbery.”68

Nineteenth-century tourists to the South relied on travel literature and fictional accounts to inform them about the region’s offerings—from health resorts in the mountain South to trees draped in Spanish moss in the Lowcountry to the factories in the emerging urban South. The elite tourists of the nineteenth century gave way to the middle-class tourists of the twentieth, just as train travel gave way to automobile travel. The increasing numbers of tourists to the South contributed to the expansion of the South’s tourist trade. Very few southern states committed resources to tourism in the nineteenth century, but by the twentieth century it was obvious to more than a few entrepreneurs that travelers from the Northeast and the Midwest represented a boon to the southern economy. By the 1920s, southern states were much more likely to invest in tourism and the roads and highways needed for travel. Moreover, southerners recognized what nonsoutherners expected to see of the South and were more than willing to give it to them. It is no surprise that the black driver in Savannah who took Mildred Cram to see the Hermitage plantation recognized that he was part of the South’s tourist trade, just as the hucksters in Atlanta sold out of towners tours of the sites found in Gone with the Wind. The South and southerners recognized that the region and its people were a cultural commodity—a commodity from which they intended to profit.