Chapter Five: Another Bloody Murder

When we crossed the cattleguard that put us back on the ranch, I felt a change come over me.

In town I had been just another happy-go-lucky dog without a care in the world. But back on the ranch, I felt that same crushing sense of responsibility that’s known to people in high places, such as presidents, prime ministers, emperors, and such. Being Head of Ranch Security is a great honor but also a dreadful burden.

I remembered the chickenhouse murder. I still didn’t have any suspects, or I had too many suspects, maybe that was it. Everyone was a suspect, well, everyone but the milk cow, and I had pretty muchly scratched her off the list. And the porcupine, since they only eat trees.

But every other creature on the ranch was under the shadow of suspicion. Except Drover. He was too chicken to kill a chicken.

When we got home, I trotted up to the chickenhouse and went over the whole thing in my mind. While I was sitting there, lost in thought, a chicken came up and pecked me on the tail. Scared the fool out of me just for a second. I snarled at her and made her squawk and flap her wings.

That’s another thing about this job. Every day, every night you put your life on the line, and for what? A bunch of idiot birds that would just as soon peck you on the tail as tell you good morning. Sometimes you wonder if it’s worth it, and all that keeps you going is dedication to duty.

In the end, that’s what separates the top echelon of cowdogs from the common rubble . . . rabble, whatever the word is, anyway the dogs that don’t give a rip, is what I’m saying.

Well, I had nothing to work with, no evidence, no case. There wasn’t a thing I could do until the killer struck again. I could only hope that me and Drover could catch him in the act.

I decided to change my strategy. Instead of throwing a guard around the chickenhouse, we would use the stake-out approach.

“Stake-out” is a technical term which we use in this business. Webster defines “stake” as “a length of wood or metal pointed at one end for driving into the ground.” It comes from the Anglo-Saxon word staca, akin to the Danish staak.

“Out” is defined as “away from, forth from, or removed from a place, position, or situation.” It comes from the Middle English ut.

That’s about as technical as I can make it.

In layman’s terms, a stake-out is basically a trap. You leave the chickenhouse unguarded, don’t you see, and watch and wait and wait and watch until the villain makes his move, and then you swoop in and get him.

It’s pretty simple, really, when you get used to the terminology.

At dark, me and Drover staked the place out. We hid in some tall weeds maybe thirty feet from the chickenhouse.

Time sure did drag. The first couple of hours we heard coyotes howling off in the pastures. Drover kept looking around with big eyes. I thought he might try to slip off to the machine shed, but he didn’t. After a while, he laid his head down on his paws and went to sleep.

I could have kept him awake, I mean, pulled rank and demanded that he stay awake, but I thought, what the heck, the little guy probably needed the sleep. I figgered I could keep watch and wake him up when the time came for action.

Then I fell asleep, but the funny thing about it was that I dreamed I was awake, sitting here and standing guard. I kept saying, “Hank, are you still awake?” And Hank said, “Sure I am. If I was asleep, you and I wouldn’t be talking like this, would we?” And I said, “No, I suppose not.”

Seems to me it’s kind of a waste of good sleep to dream about what you were doing when you were awake, but that’s what happened.

I heard something squawk, and I said, “Hank, what’s that?”

“Nuthin.”

“You sure?”

“Sure I’m sure. You’re wide awake and watching the stake-out, aren’t you?”

“I think so, yes.”

“Then stop worrying.

The squawking went on and the next thing I knew, Drover was jumping up and down. “Hank, oh Hank, he’s back, murder, help, blood, we fell asleep, oh my gosh, Hank, wake up!”

“Huh? I ain’t asleep.” And right then my eyes popped open and I woke up. “Dang the luck, I was asleep! I was afraid of that.”

We dashed out of the weeds and found a body south of the chickenhouse door. The M.O. was the same. (There’s another technical term, M.O. It stands for Modus of Operationus, which means how it was done. We shorten it to M.O.)

A pattern began to emerge. The killer had struck twice and both times he had killed a white leghorn hen. (Actually, that might not have been a crucial point because there weren’t any other-colored hens on the place, but I mention it to demonstrate the kind of deep thinking that goes into solving a case of this type. You can’t overlook a single detail, even those that don’t mean anything.)

But the most revealing clue was that the murderer hadn’t dragged his victim off. That meant that he hadn’t killed for food, but only for the sport of it. In other words, we had a pathagorical killer on the loose.

This was very significant, the first big break in the case. At last I had an M.O. that narrowed the suspects down to coyotes, coons, skunks, badgers, foxes . . . rats, it hadn’t eliminated anybody and I was right back where I started.

I hunkered down and studied the body. It was still warm. Warm chicken. My mouth began to water and I noticed a rumble in my stomach. This fresh evidence was pointing the case in an entirely new direction.

“Uh Drover, why don’t you run on and get some sleep? You’ve had a tough day.”

“Oh, I’m awake now.”

“You look sleepy.”

“I do?”

“Yes, you do, awful sleepy. Your eyes seem kind of baggy.”

“Don’t you think we should sound the alarm?”

“Not just yet. I need to do a little more study on the corpse.” My stomach growled real loud.

Drover perked his ears. “What was that?”

“I didn’t hear anything.”

He waited and listened. I concentrated on making my stomach shut up. You can do that, you know, control your body with your mind, only it didn’t work this time. My stomach growled again, sounded like a rusty gate hinge.

“What is that?”

“Rigor mortis,” I said. “Chickens do that. Run along now and get some sleep. We’ve got a big day ahead of us.”

“Well, okay.” He started off and heard my stomach again. He turned around and twisted his head and stared at me. “Was that you?”

“Don’t be absurd. Good night, Drover.”

He shrugged and went on down to the gas tanks. I gave him plenty of time to bed down, get comfortable, snap at a few mosquitoes, and fall asleep. My mouth was watering so much that it was dripping off my chin.

When everything was real quiet, I snatched up the body, loped out into the horse pasture, and began my postmortem investigation. It was very interesting.

I didn’t hurry this part of the investigation. I labored over my work for several hours and fell into a peaceful sleep.

When I awoke it was bright daylight. I could feel the rays of the sun warming my coat. I glanced around, trying to remember where I was, and when I figured it out, my heart almost stopped beating.

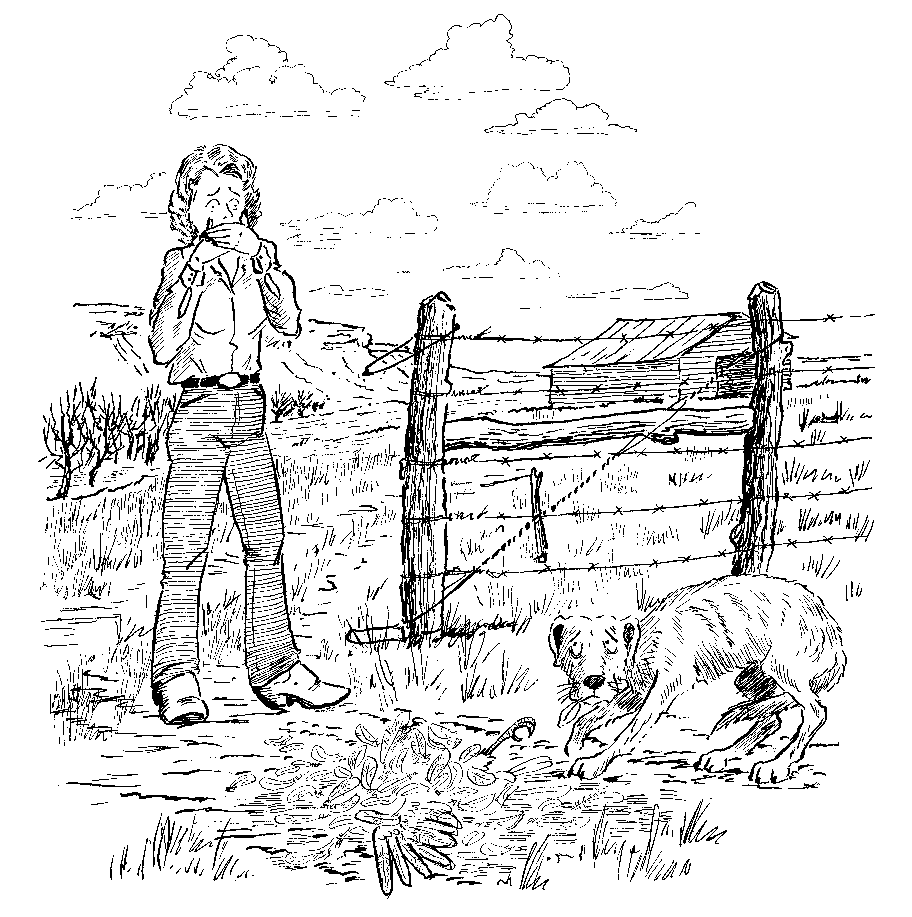

I was lying in the center of a circle of white feathers, and several more feathers were clinging to my mouth and nose. My belly bulged, and Sally May was standing over me, a look of horror on her face.

“Hank! You’re the one! Oh Hank, how could you!”

Huh? No wait, there had been a mistake. I had only . . . well, you see, I just . . . the chicken was already dead and I thought . . . hey, listen, I can explain everything . . .

It must have looked pretty bad, me lying there in the midst of all that damaging evidence. Sally May headed down to the house, swinging her arms and walking fast.

I didn’t know what to do. If I ran, it would look bad. If I stayed, it would look bad. No matter what I did, it would look bad. Maybe eating the dern chicken had been a mistake.

I was still sitting there, mulling over my next course of action, when Sally May returned with her husband.

“There, look. You see who’s been killing the chickens? Your dog!”

I whapped my tail against the ground and put on my most innocent face. Loper and I had been through a lot together. Surely he would know that his Head of Ranch Security wasn’t a common chicken-killing dog. He had to trust me.

But I could see his face harden, and I knew I was cooked. “Hank, you bad dog. I never would have thought you’d do something like this.”

I didn’t! It was all a mistake, I’d been framed.

“Come here, Hank.” I crawled over to him. He picked up the chicken head which was lying on the ground. I hadn’t eaten it because I’ve found that beaks are hard to swaller. He tied a piece of string around the head and tied it around my neck. “There. You wear that chicken head until it falls off. Maybe that’ll help you remember that killing hens doesn’t pay around here.”

They left, talking in low voices and shaking their heads. I tried to bite the string and get that thing off my neck, but I couldn’t do it. I was feeling mighty low, mighty blue. I was ashamed of myself, but also outraged at the injustice of it.

I headed down to the corral to find Drover. Instead, I ran into Pete the Barncat, just the guy I didn’t want to see. He was sunning himself in front of the saddle shed—in other words, loafing, which is what he does about ninety-five percent of the time. The mice were rampant down at the feed barn, but Pete couldn’t work a mouse patrol into his busy schedule. It interfered with his loafing. That’s a cat for you.

He saw me before I saw him. He yawned and a big grin spread across his mouth. “Nice necklace you got on, Hankie. Where could a feller buy one of those?”

You have to be in the mood for Pete, and I wasn’t. I made a dive for him and he escaped instant death by a matter of inches. He hissed and ran, and I fell in right behind him.

I chased him around the corrals. He hissed and I barked. There were several horses in the west lot and they all started bucking and kicking up their heels. It was my lousy luck that Slim happened to be riding one of them—a two-year-old colt, as I recall—and he started yelling.

“Hank, get outa here! Whoa, Sinbad, easy bronc!”

Nobody around here ever yells at the cat. Why? I don’t know, I just don’t understand.

I gave up the chase. I would settle accounts with Pete some other day. I loped over to the gas tank, looking for Drover. He heard me coming, sat up, saw the chicken head around my neck, turned tail, and sprinted for the machine shed as fast as he could go.

“Drover, wait, it’s me, Hank!”

He kept going. I guess he didn’t want to get involved with a criminal.

I went down to the gas tank and lay down. Boy, I felt low. I tried to sleep but didn’t have much luck. That chicken head was starting to smell, and it reminded me all over again of the injustice of my situation.

Off in the distance, I could hear Pete. He was still up in the tree he had climbed to escape my attack, and he was singing a song called “Mommas, Don’t Let Your Puppies Grow Up to Be Cowdogs.” Now and then he would stop singing, and I would hear him laughing. Really got under my skin.

I lay there brooding for a long time. Then I pushed myself up and all of a sudden it was clear what I would have to do. They had left me no choice.

I took one last look at my bedroom there under the gas tank, and started up the hill. As I passed by the machine shed door, Drover stuck his head out.

“Psst! Where you going?”

I trotted past. “I’m leaving.”

He crept out, glanced around to see if anybody was watching, and came after me. “Leaving?”

“That’s right. I quit, I resign.”

His jaw dropped. “You can’t do that.”

“You just watch me. This chicken head was the last straw. I’m fed up with this place. I’m moving on.”

“Moving . . . where you going?”

“I don’t know yet. West, toward the setting sun.”

He was quiet for a minute, then, “I’ll go with you.”

“No you won’t.”

“How come?”

“Because, Drover, I’m starting a new life. I’m gonna become an outlaw.”

The breath whistled through his throat. “An outlaw!”

“That’s right. They’ve driven me to it. I tried to run this ranch, but it just didn’t work. I’m going back to the wild. One of these days, they’ll be sorry.”

“But, Hank . . .”

“Good-bye, Drover. Take care of things. I’m sorry it has to end this way. Next time we meet, I won’t be Hank the Cowdog. I’ll be Hank the Outlaw. So long.”

And with that, I trotted off to a new life as a criminal, outcast, nomad, and wild dog.