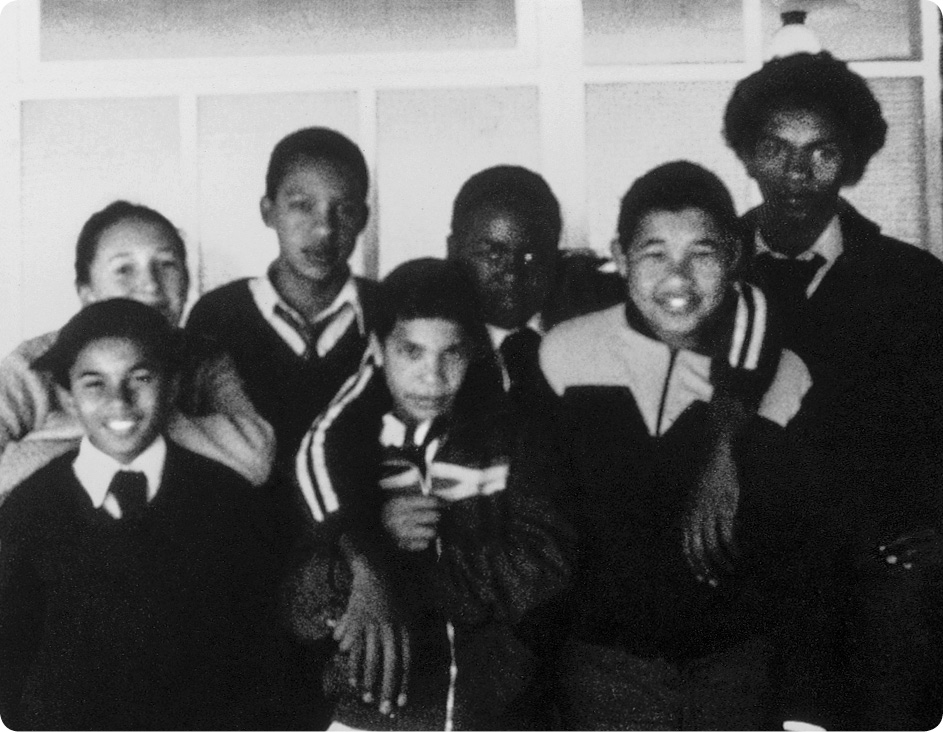

Bryan, me, and José from Ecuador, Grajagan, Java, 1979

SEVEN

CHOOSING ETHIOPIA

Asia, Africa, 1979–81

BRYAN LOATHED BALI. HE WROTE AN ARTICLE FOR TRACKS—IT carried, by tradition, both our names, though I only gave it a light edit—mocking the notion, then widespread among Australian surfers, that Bali was still an unspoiled paradise of uncrowded waves and mellow Hindu natives. In fact, he wrote, it was overrun with surfers and other tourists. It was a place where one could “see topless and bottomless Europeans of both sexes,” “listen to the lies of surfers from all over the world,” “hire a board carrier and experience the dizzying thrill of colonialism,” and “tell people you’re from Cronulla when you’re really from Parramatta,” the latter being a less cool Sydney suburb than the former.

I agreed that Bali was overrun, and the collision of mass tourism and Indonesian poverty was grotesque, but the place suited me nonetheless. We stayed in a cheap, clean losmen (guesthouse) in Kuta Beach, ate well for practically nothing, and surfed daily. I found a good writing spot in a college library in Denpasar, the provincial capital, catching a bus there each morning. It was a cool, quiet refuge on a hot, noisy island. My novel was rocking along. A street vendor with a little turquoise cart would show up outside the library at midday, my signal to knock off. He served rice, soup, sweets, and satay through the opened windows of campus offices. I liked his nasi goreng—fried rice. In the afternoons, if there was swell, Bryan and I headed out the Bukit Peninsula, where a brace of great lefts broke off limestone cliffs. There were good waves around Kuta too, even on small swells, and, when the wind blew southwest, in a resort area on the east coast, Sanur.

The spot that sank its hooks in me the deepest was a sweeping, already famous left called Uluwatu. It was out on the southwestern tip of the Bukit. There was an eleventh-century Hindu temple, built of hard gray coral, perched on the edge of a high cliff just to the east of the wave. You entered the water, at high tide, through a sloshing sea cave. Uluwatu got big, and on bigger days, when the wind was light offshore, the long blue walls did something I had never seen elsewhere. In discrete, well-separated places along the swell line, they gently feathered far, far ahead of where you were surfing—hundreds of yards ahead, and hundreds of yards from shore. There were apparently a series of narrow rock ridges running out to sea from the inside reef, formations shallow enough to make a big wave feather but not, at least on the swells we surfed, to make it break. It was unsettling at first, but then, after a few screaming rides on massive waves that did not close out, the sight of those distant feathering sections just heightened the joy of rocketing around in the breaking part of the wave, since those strange wafts of spray out in the bay would soon become, you came to trust, solid sections on the inside shelf.

Inside Uluwatu was known, unoriginally, as the Racetrack. It was shallow and very fast, with sharp coral that left its claw marks on my feet, arms, and back. One afternoon, it scared me badly. The crowd, which could be thick at Uluwatu, even in 1979, had thinned out, which I found mysterious, since the surf was excellent. There were maybe five of us still out. The tide was low. The waves were big and quick. I could see twenty or thirty guys on the cliff, all squinting into the dropping sun, which should have caused me to ask, Why are they watching and not surfing? I got a couple of sweet rides, and then a wave that answered the question I had neglected to ask. It was well overhead, dark-faced, thick, and I, sky-high on testosterone, made the mistake of driving hard and low into the Racetrack. All the water drained off the reef. The tide was too low to surf down here at this size. That was why everyone had left. I could not pull out. It was too late for that. I could not dive off. There was no water. I got the deepest backhand barrel of my life. It was very dark, very noisy. I did not enjoy it. In fact, even as it became clear that I might actually make it, I wished, with a weird bitter awareness of the irony of it, that I could be anywhere else on earth. It should have been a moment of satori, a thunderbolt of enlightenment after long, patient practice. Instead, I was miserable because fear, entirely justified, filled my heart and brain. I made the wave, but I escaped horrible injury, if not worse, by pure dumb luck. Pulling in had been a low-odds survival move. Stupidity had put me inside that tube. If I had a chance to do it over again, I wouldn’t.

There were so many surfers in Kuta, it was like attending a world conference of the wave-obsessed. They might all have been lying, but there were people talking surf on beaches and street corners, in bars and cafés and losmen courtyards, 24/7. Max, who had once mocked me and Bryan, would have had a field day with this mob. But I found it oddly moving, the intensity with which a group of guys could talk about the lines of a board standing up against a wall—its release points, its rocker—or the way that surfers often dropped to the ground to draw in the dirt the layout of their home breaks for guys from other places, other countries. Their stories, they felt, would make no sense if their listeners didn’t understand exactly how a reef back in Perth caught a west swell. They lost themselves in diagrams more detailed than anyone wanted. Some of this strange ardor could be put down to homesickness, or simply to the countless hours spent surfing and studying that particular reef, but a good part of it was also, it must be said, dope-fueled. Surfers in Bali, together with the legions of nonsurfing Western backpackers, smoked daunting quantities of hash and pot. Bryan and I were the rare abstainers. Cannabis had started making me anxious in college; I hadn’t smoked any in probably five years. Bryan liked to call everything except alcohol “false drugs.”

I had begun trying to interest magazines in travel pieces. My first assignment came from the Hong Kong edition of a U.S. military publication called Off Duty. I had never seen the magazine (I have still never seen it), but the $150 they offered sounded grand. They wanted a story about getting a massage in Bali. Massage ladies were everywhere in Kuta, with their pink plastic baskets of aromatic oils. I was too shy to approach one on the beach, where pale bodies were being kneaded by the dozen all day long. But as soon as I mentioned my interest, the family that ran our losmen produced a sinewy-armed old woman. The children of the establishment laughed as she eyed me with sadistic pleasure and ordered me down on my belly on a cot in the courtyard. I was actually frightened as she dove into my back muscles with her powerful hands. I had torn an upper back muscle on the railroad, while yanking on a rusted cut lever in Redwood City, and it had never properly healed. I imagined this macho masseuse tearing into the sore spot and doing more damage. I wondered uneasily if such an episode might at least make good article copy. The injury had a bittersweet history already. When it happened, my fellow trainmen advised me to take no money, and sign no papers, from the company. This could be my million-dollar ladder, they said—the piece of defective equipment that allowed me to sue the railroad, get rich, and retire young. I considered such thinking contemptible, and so a few days later, when my back felt better, I cashed a check, signed a release, and returned to work. Of course, my back started hurting again the next day, and had ached ever since. But the masseuse didn’t hurt me. Her fingers found the messed-up muscle, explored it, and worked it long and gently. It stopped aching that day, and the old throb didn’t resume for weeks.

At some point I got sick. Fever, headache, dizziness, chills, a dry cough. I was too weak to surf, felt too awful to work. After a day or two, I dragged myself to Sanur, lying in the back of a minibus, and found a German doctor in one of the big hotels. He said I had paratyphoid, which wasn’t as bad as typhoid. I probably got it from street food, he said. He gave me antibiotics. He said I would not die. I had almost never been sick before, which meant I had no experience of debility to draw on. I sank into a fretful derangement, sweating, listless, self-despising. I began to think, more desperately now, that I had wasted my life. I wished I had listened to my parents. (Patrick White: “parents, those arch-amateurs of life.”) My mother had wanted me to become a Nader’s Raider—one of the idealistic young lawyers working for Ralph Nader, exposing corporate misdeeds. Why hadn’t I done that? My father would have liked me to become a journalist. His hero had been Edward R. Murrow. As a young man, he had worked as a gofer for Murrow and his buddies in New York. Why hadn’t I listened to him? Bryan came and went from the room, looking dubiously at me, I thought, as I sloshed in self-pity. No, he said, the waves weren’t much good. Bali still sucked. Where was he sleeping? He had met a woman. An Italian, I gathered.

We were getting mail—poste restante, Kuta Beach. But I had not heard from Sharon in weeks. I began to feel forgotten, angry. One morning, when I was slightly stronger, I walked slowly to the post office. There were cards and letters from family and friends but nothing from Sharon. I thought about sending a telegram but noticed a group of tourists gathered by a set of old wall phones under a sign, INTERNASIONAL. The telephone—what a concept. I called her. It was only the second or third time we had spoken in a year. Her voice was like music from another life. I was entranced. She and I wrote a great many letters, but the vast, delicately balanced distance between us collapsed when she murmured in my ear in real time. She was alarmed when I said I was sick. I should get well. She said she would meet me in Singapore at the end of June. This was major news. It was mid-May.

I got well.

• • •

INDONESIA IS A BIG PLACE, with more than a thousand miles of coast exposed to Indian Ocean swells. Only Bali had been much explored by surfers. Bryan and I were ready to look for waves elsewhere. On the southeastern tip of Java, there was a fabled wilderness left known as Grajagan. An American, Mike Boyum, had built a camp there in the mid-’70s, but nothing had been heard from him recently. It seemed like a logical place to start. We sold our extra Aussie boards. From among the hordes in Bali, we found two accomplices—an Indonesian-American photographer from California named Mike, and a blond Ecuadorean goofyfoot named José.

It was a difficult expedition. We bought supplies in an East Java town, Banyuwangi, a long way from the coast. Vehement haggling seemed to be the local norm for every transaction, at least with orang putih—white men. Mike’s command of Bahasa Indonesia, which we had thought at first was good, disintegrated under pressure. I became chief haggler. (Bahasa Indonesia is an easy language to learn if you don’t mind speaking it badly. It has no verb tenses, and in much of the country it is—or at least was then—nobody’s first language, which helped level the field for a foreigner.) At the coast, in the village of Grajagan, we needed a boat to take us ten miles across a bay to the wave. More wild, sweaty haggling, many hours. The villagers had seen surfers before, they said, but none in the past year or so. I drew up a contract in my journal, which a fishermen named Kosua and I signed. They would take us across for twenty thousand rupiah (thirty-two dollars), and come back for us in a week. They would supply eight jerry cans of freshwater. We would leave the next morning at 5 a.m.

The boat we sailed in was nothing like the delicate, colorful little jukung outriggers that fished off Uluwatu. It was a broad-beamed, heavy-bottomed beast, powered not by a patch of sail but by a large, noisy, ancient outboard with a strangely long propeller shaft. It carried a crew of ten. Five minutes into our voyage, it capsized in the surf in front of the village. Nobody got hurt but everybody got upset, and a lot of stuff got wet. Kosua wanted to renegotiate our contract. He tried to argue that this trip was more dangerous than we had let on. That was rich, I thought, after crashing on a sandbar that he had to negotiate every time he took out his boat. So we haggled for another day or so, until the surf got smaller. Then we went.

Grajagan the surf spot, known locally as Plengkung, was way out on a roadless point where the thick jungle was said to be one of the last redoubts of the Javan tiger. Kosua dropped us in a cove about a half mile down the beach from some ramshackle structures that had been Boyum’s camp. It was low tide, and there were great-looking waves breaking off a wide, exposed reef beyond the camp. We started humping our gear in the heat, as Kosua motored away. The jerry cans were hideously heavy. It was all I could do to drag one along the sand. Mike couldn’t even manage that. Bryan carried two at a time. I knew he was strong, but this was ridiculous. Even more impressive: after we got to the camp and all fell prostrate in the shade, gasping for water, Bryan opened a jerry can, tasted the water, spat it out, and said calmly, “Benzine.” What was impressive was his calmness. He went down the line of plastic cans. Six of eight were undrinkable. They had been used to carry fuel, and had not been properly cleaned. Bryan dragged the two cans of potable water to the base of a tree. “Looks like strict rationing,” he said. “Want me to be in charge?”

Mike and José appeared to be in shock. They were silent. I said, “Sure.”

The whole Grajagan misadventure went like that. Screwups, mishaps, constant thirst, and Mike and José half-catatonic. Bryan and I seemed, by comparison, seasoned and resourceful. The pattern had started in Banyuwangi. As they got daunted, we divided tasks and took care of business. Bryan and I had been traveling together for more than a year now, and it felt good—redeeming, even—to know how completely we could rely on each other. The division of water, for that matter, would be fair, I knew, down to the drop.

Boyum had built several bamboo tree houses, all but one of which had collapsed. We slept, gingerly, in the uncollapsed one. We saw no tigers, but we heard large beasts at night, including wild bulls known as banteng and angry-sounding boars rooting around the trunk of our tree. Sleeping on the ground was out of the question.

Our bad luck continued during our first surf session, when Bryan came up from a wipeout holding the side of his head, his face white with pain. We suspected a burst eardrum. He was out of the water for the rest of the week.

I tried to assure him that the waves were not as good as they looked, and they really weren’t. They looked incredible—long, long, long, fast, empty lefts, six feet on the smaller days, eight-feet-plus when the swell pulsed. I now think that José and I were surfing the wrong place. For me, it was natural to move up the line, toward the top—to the first place where a wave was catchable. At Grajagan it was big and sectiony and mushy up top, but that’s where I went, and José followed my lead. I figured I could connect some of the racier parts of the wave farther down. Except I rarely could. There were always flat spots, then unmakable sections. I was misreading the reef completely. It apparently never even occured to me to move down inside, to try to find a corner in there where a makable takeoff led to a cleaner, better-peeling wave. On the biggest day, José wanted no part of it, and Mike, who had rarely left his mosquito net, convinced me to paddle all the way up to where it was genuinely huge. He even talked me into wearing a little white wetsuit vest he carried. It would make a nice contrast with the turquoise water and my brown arms, he said. I caught one monster wave, against my better judgment, barely making the drop on my trusty New Zealand pintail. Mike said he got the shot, though I never saw it.

In fact, the only time that I knew for sure that he even had film in his camera was a year or two later, when someone sent me a full-page photo, shot by Mike, from an American surf mag. There was empty low-tide Grajagan, with me standing in the foreground, pintail under arm. The waves, as usual, looked magnificent.

Frustration is a big part of surfing. It’s the part we all tend to forget—stupid sessions, waves missed, waves blown, endless-seeming lulls. But the fact that frustration was the main theme of my surfing during a week of big, clean, empty waves at Grajagan is so improbable to other surfers that I haven’t forgotten it. Bryan never believed it either.

• • •

MY PARENTS HAD SENT US a pair of baseball caps from a TV movie they had worked on, Vacation in Hell. People would ask what the phrase meant. My Bahasa Indonesia was not up to a good translation. Bryan took to saying, “You’re looking at it, friend.”

Mike, when we parted—he and José went straight back to Bali—had solemnly advised us, “Indonesia is a death trap.” That was melodramatic, but it was not easy traveling, on the super-cheap, up through Java and Sumatra, with surfboards. Every bus and van we caught was uncomfortably, insultingly overcrowded, as operators tried to squeeze more profit, literally, out of passengers. Still, I had to admire the heroics of the boy conductors, their incredible feats of balance, agility, and strength, clinging to doorframes at hair-raising speeds, their rapid-fire bargaining over fares, and in some cases their adroit public relations, keeping the customers at least half-satisfied. Barefoot, dressed in rags, these brilliant kids made American trainmen, always carefully dismounting locomotives and freight cars per our detailed instruction manuals, always wearing our steel-toed boots, look like pikers.

We caught a train across part of Java. Hanging out the window to catch the breeze, I was struck by how, for somebody seeing Indonesia from a train, the main business of the nation seemed to be defecation. Every stream, river, weir, and rice-paddy canal that the tracks crossed seemed to be lined with farmers and villagers placidly squatting. It was a tour of the world’s biggest, most picturesque toilet, and it reminded me that I had vowed to be more careful about what I ate and drank after my Bali paratyphoid follies. I was still eating at street stalls, though, and we were still staying in dives. I had contracted malaria, in any case, at Plengkung. But I didn’t know that yet. Bryan’s eardrum, meanwhile, was indeed burst, said a doctor in Jakarta. He gave him some drops, and said it would heal.

Rural Southeast Asia, in its intense tropicality, bore a superficial resemblance to rural Polynesia. But the differences between the two regions were far more pronounced. Vast civilizations had risen here on the surplus created by rice-based agriculture. Hundreds of millions of people lived and jostled here, in incomprehensibly complex caste societies. I took to interviewing people, semiformally—it was an odd thing to do, with no particular project in mind, but I was curious and they often seemed pleased to be asked—about their family histories, income, prospects, hopes. A rice farmer near Jogjakarta, who was a retired army captain, gave me a detailed account of his career, his farm’s operating expenses, his oldest son’s progress at university. Across nearly every story I heard, however, a thick veil fell around the period of 1965–66, when more than half a million Indonesians were killed in massacres led by the military and Islamic clerics. The main targets had been communists and alleged communists, but ethnic Chinese and Christians had also died or been dispossessed en masse. The Suharto dictatorship that emerged from the bloodbath was still in power, and the massacres were suppressed history, not taught in schools or publicly discussed. A pedal-taxi driver in Padang, a port city in western Sumatra, told me quietly about spending years in prison as a suspected leftist. He had been a professor before the great purge. He liked Americans, but the American government, he said, had aided and applauded the killing.

Sumatra was for us a refreshing change from Java. More mountainous, less crowded, more prosperous, less stifling, at least in the areas we traversed. We had a treasure map, given to us in the South Pacific by an intrepid Australian kneeboarder who said she had surfed a great wave on Pulau Nias, an island west of Sumatra. It was no longer a secret spot, apparently, but a key threshold had not yet been crossed—no photos had been published. We caught a small, spartan, diesel-powered ferry from Padang. It was about two hundred miles to Nias, and a storm clobbered us the first night out. We wallowed in total darkness. At times, terrifyingly, we seemed to lose steerage. Waves washed across the deck. The only cabin was a small, grimy plywood hut for the helmsman. Most of the passengers were sick. But people were amazingly tough. Nobody screamed. Everybody prayed. We were lucky no one went overboard. We were lucky the old tub didn’t sink. We putt-putted into Teluk Dalam, a little port on the south end of Nias, on a muggy gray morning. There was nothing about Teluk Dalam, I thought, that would have been out of place in a Joseph Conrad novel. Nias had a population of five hundred thousand and no electricity.

The wave was about ten miles west, near a village called Lagundri. The kneeboarder was correct. It was an immaculate right. It broke off a point, but it was really a reefbreak, since the wave did not follow the shoreline. It stood up distinctively, a ruler-straight wall, when it hit the reef, but then it peeled across, away from the shore, without sections, for probably eighty yards, barreling beautifully into the wind, before it hit deep water. A small company of tall coconut trees on the point leaned out over the water, as if they wanted to get a better look at the wave. It was a splendid sight, truly. Lagundri Bay was horseshoe-shaped and deep. The village, roughly a mile down from the point and separated from the beach by a palm grove, was a modest collection of fishermen’s shacks except for one imposing, rather ornate three-story wooden house with an elaborately peaked roof. This was the losmen. There were four or five surfers staying there, all Aussies. If the other surfers were dismayed that we showed up, they hid it well. We hung our mosquito nets on a second-floor balcony.

It was on that balcony that Bryan told me he was bailing. I remember, when he said it, that I was reading a biography of Mark Twain, by Justin Kaplan, that we had traded back and forth. It was a hot afternoon. We were waiting out the worst of the heat before a late-day go-out. The news was not a complete surprise. Bryan had been muttering about meeting Diane in Europe during her summer vacation.

Still, it hurt. I kept my eyes on the book.

It wasn’t me, he said, after I asked. He was just tired. And homesick. And sick of traveling. Diane had given him an ultimatum, but he was ready to go. He would look for a cheap flight in Singapore or Bangkok, probably head out in late July. That was six or seven weeks away.

• • •

WE SURFED. The swell was remarkably consistent for the first week or so. The brilliance of the wave seemed only to increase. It was ridable at all tides. It never seemed to blow out. There was a little reverse current running out to sea from the bottom of the bay that helped keep the surface groomed in all conditions. Paddling out was absurdly easy. You walked to the point, beyond the wave, slipped through a keyhole in the reef, and arrived in the lineup with hair dry. Except for being a world-class right, it was the categorical opposite of Kirra. There was no demonic current to fight. If every surfer within five hundred miles had been out at the same time, there would still have been no crowd. And where Kirra’s essential quality was breathtaking compression, the wave on Nias felt like pure expansion. It invited you to move farther up, get in earlier, take a higher line, pull in deeper. The takeoff was steep but straightforward. You just had to get over the ledge and be on the wave when it jacked. There was no time to carve big turns on the main wall. It was a run-and-gun wave, with a glorious tube if you took a high line and timed it well on a wave that opened up. It wasn’t a top-to-bottom barrel—it was what is known as an almond-shaped barrel—although it broke hard enough to snap boards. The wave wasn’t extremely long, like Tavarua, but neither was it dangerously shallow. And the wave on Nias had an extraordinary grace note. The last ten yards of the main wall, just before it hit deep water, stood up extra-tall. The face there was, for no obvious reason, often several feet taller than the rest of the wave. This great green slope, particularly the top third of it, begged for a high-speed flourish, a maneuver to remember, a demonstration of both gratitude and mastery.

I peaked, in some ways, as a surfer on Nias, although I didn’t know it at the time. I was twenty-six, probably stronger than I had ever been, as quick as I would ever be. I was on the right board, on the right wave. I had been surfing consistently for a year-plus. I felt like I could do almost anything on a wave that occurred to me. When the surf got bigger, late that week, I doubled down and surfed with more abandon. The extra-tall end-section let me bank off the top from a height that I had never before attempted, and mostly I came down cleanly on my board. I did know that I had never surfed so loosely in waves that size. I felt immortal.

• • •

ALTHOUGH IT WAS THE DRY SEASON, a two-day rainstorm flooded the village and filled the bay with brown freshwater, which seemed to kill the waves.

I went to bed feeling weird and woke up with a fever. I assumed it was a paratyphoid relapse. More likely, it was malaria. I started feeling less immortal. Maybe Indonesia was a death trap. Three Australian surfers had discovered the wave at Lagundri in 1975, and one of them, John Giesel, after repeated bouts of malaria, had died, reportedly of pneumonia, nine months later. He was twenty-three. One of the two guys who first surfed Grajagan, an American named Bob Laverty—the other guy was Mike Boyum’s brother—died only a few days after returning to Bali. He drowned at Uluwatu. Mike Boyum survived Indonesia but got into cocaine smuggling, went to jail in Vanuatu, and later died, while living under an alias, at a great wave he found in the Philippines.

I was also tired, and homesick, and sick of traveling. I wasn’t tempted to quit Asia with Bryan, but I was having trouble remembering exactly why I was here. There was surfing, but it wasn’t going to get any better than Lagundri. I simply couldn’t picture returning to the United States. I copied out a passage from Lord Jim: “We wander in our thousands over the face of the earth, the illustrious and the obscure, earning beyond the seas our fame, our money, or only a crust of bread; but it seems to me that for each of us going home must be like going to render an account.” I was not ready for that accounting. For one thing, I couldn’t return to the United States without finishing this novel. I thought about it constantly, filling journals with plotting, rethinking, self-castigation, and exhortations to greater efforts, but I hadn’t written any new material since Bali. Where could I hole up and get back to work? Writing felt like it justified, barely, my existence—this extremity of obscurity I had perversely chosen. But I was also starting to worry about money. We were living on a few dollars a day, but cities like Singapore and Bangkok would be a different story. Bryan had enough to get home. Running out of money in Southeast Asia could be grim. I doubted that Sharon had much saved. We would need to be frugal.

But it was farcical, gross, I knew, for me to be fretting about money in Lagundri, where the ambient ironies of the Asia Trail were never far away. The Asia Trail was the great snaking overland route from Europe to Bali, slogged down by thousands of Western backpackers since the ’60s. It was being broken into pieces in 1979 by the Iranian revolution, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was about to remove another poverty-ridden, dope-rich Shangri-la from the itinerary. But the trail, which included a main stop at Lake Toba, in north Sumatra, also had a tiny tributary that ran out to Nias. This had little to do with surfing as yet. It existed, apparently, because of the local culture, which had developed in relative isolation and included stone megaliths, spectacular ironwood architecture known as omo sebua, war dances, and hilltop villages with houses modeled after the Dutch galleons of slave-trading days. And so an odd collection of European hippies and tourists wandered up the coastal road through Lagundri. The villagers looked askance at them all, particularly the bedraggled backpackers. It was not hard to see why. Here was a large, awkward member of the global ruling elite who had probably spent more in an air-travel day than anyone on Nias could make in a year of hard work, all for the pleasure of leaving an unimaginably rich, clean place for this desperately poor, unhealthy place. Here he was struggling blindly down the road under an enormous pack, disoriented and ignorant and sweating like a donkey. He wanted to see Asia from the ground, not from the Hilton height of some air-conditioned resort that any sane person would prefer. The complex ambitions and aversions that brought the poor backpacker seven thousand miles to struggle and suffer from dysentery, heatstroke, or worse in the equatorial jungle—anything to be a “traveler” and not a “tourist”!—were perhaps impossible to untangle, but it was well known that he brought so little money that he was hardly worth hustling.

Bryan and I were in the same economic bracket, of course. And being a rich orang putih in a poor brown world still sucked irredeemably. We, that is, sucked.

The family that ran the losmen in Lagundri was Muslim, which made them unusual on Nias, which is predominantly Christian. In the nearby villages, the churches shook with fervent song. On the jungle paths, small unsmiling men with machetes tucked in their waistbands carried enormous jute bags of coconuts. Our hosts were affable, and relatively cosmopolitan—they came from Sumatra—and they warned us against going beyond the village at night. The local Christianity was strictly nominal, they said. During World War II, when the island was cut off from the outside world, congregations had swiftly reverted to precolonial practice and eaten the Dutch and German missionaries among them. I was unable to verify this gory gossip.

My fever alternated with chills. A headache was constant. I was taking chloroquine, a popular malaria prophylaxis, unaware that it was useless against many local strains of the disease. Indonesian villagers often asked for pills without specifying what kind. Vitamins, aspirin, antibiotics—there seemed to be a general faith in pills. At first I thought the requests might be for sick relatives or friends, or for stockpiling against illness, but then I saw perfectly healthy-looking people pop whatever was handed over, no questions asked. It would have been funny if it weren’t so ominous. Now that I was sick, people left me alone. Babies wailed. I listlessly read a collection of Donald Barthelme stories. Lines stuck in my head. “Call up Bomba the Jungle Boy? Get his input?” Boney M’s execrable, inescapable “Rivers of Babylon” wheezed from a village teenager’s tape deck.

I listened to Bryan and the Aussies shooting the breeze. Bryan was on a roll. He had them blowing Sumatran coffee through their noses. I heard him say, “Oh yeah, if a surf spot’s too far from town in the States, we just call up the Army Corps of Engineers and they move it. Takes two or three days, a lot of trucks, they have to close the whole highway. Sometimes they bring the whole bay, other times just the reef and the wave. You should see it going down the road—guys still surfing it and everything. They have to go really, really slow. It’s quite an operation.”

I would miss him unspeakably. He said it wasn’t me, but I knew it partly was. We pulled together nearly effortlessly now, and we hadn’t quarreled in months, but the subterranean dynamics of our partnership had not changed. I was after something, whatever it was. And the chemistry of my brashness and what Bryan called his passivity, which he had been noting since Air Nauru and the Guam Hilton, was not doing him any good. He did not want to feel like he was along for the ride. He had to get away. But what would this long, strange trip be like without him? He and I spoke a language no one else understood. “Oh, wow, a new experience”—that was what we were supposed to say after an earthquake, or if someone stole our car, according to Teka of Tonga. But we said it after smaller fiascoes—hell nights on leaky ferries, days of unslaked thirst brought on by dirty jerry cans. “Radio Ethiopia”—that was an unlistenable Patti Smith song, some secondhand Rimbaud trope. But it stood for all faux-exotic hipster posing—names dropped in New York of places never visited, let alone lived through. We felt superior to, if also vaguely threatened by, all that. Those were the people getting on with careers in the arts, having what Bryan sometimes called Suckcess. Now he was going back to the United States. I was staying in Ethiopia. I was silently envious.

I started feeling stronger, started taking little walks. On a jungle path I met an old man who reached out and silently patted my belly. It was his way of saying good morning.

“Jam berapa?” What time is it? That was the question kids loved to ask, pointing at their watchless wrists.

“Jam karet.” Rubber time. It was a stock joke answer, meaning that time was a flexible concept in Indonesia.

People I met would often demand, “Dimana?” Where are you going?

“Jalan, jalan, saja.” Walking, walking, only.

Everybody in Indonesia always wanted to know if I was married. It was rude to answer, “Tidak”—no. That was too blunt. It disrespected marriage. Better to say “Belum”—not yet.

I wondered what Sharon would make of Nias. She had been dauntless in Morocco, game for any casbah detour. I began telling people in Lagundri that I was going to Singapore but would be back in a few months. They put in their orders: a man’s silver Seiko automatic watch; a Mikasa volleyball; a guestbook for the losmen. I started a list of things I wished we’d brought: honey, whiskey, duct tape, dried fruit, nuts, powdered milk, oatmeal. More protein would be welcome. Meat and even, oddly enough, fresh fish were rarities in Lagundri. Our meals were mostly rice and collard greens, with hot chilies to help fight bacteria. Like everyone, we ate with our hands. A fisherman in Java had taught me the best way to eat rice with your fingers. You used the first three fingers as a trough and the back of the thumb as a shovel. It worked. But I needed more food, more vitamins. My boardshorts were falling off my hips.

The sun came back out. The mud in the bay cleared up.

I caught a ride into Teluk Dalam on the back of a motorbike. I had heard that there was a shop in town with a generator and an icebox. I found the shop, and put two large bottles of Bintang, the Indonesian version of Heineken, in the icebox. I wandered around town, sent Sharon a telegram reconfirming our plans to meet. Then, when the beers were cold, I packed them in sawdust and raced back to Lagundri. I presented them to Bryan on the second-floor balcony, still icy. I thought he might weep with joy. I nearly did. Few things in my life have tasted better than those beers. Even we were speechless.

Everything had a valedictory feel. Bryan asked me to take a picture of him “for the grandkids.” He stood on the beach with his board, looking mock-heroically into the sunset. He was wearing a sarong, which everybody, including both local men and foreigners, normally did, but Bryan normally didn’t.

The surf got good again. But it always seemed to be late afternoon, the golden hour. On our last evening, without any discussion, Bryan and I took off on a wave together—something we never did. We rode for a while, then straightened off and rode the whitewater on our bellies, side by side, across the reef, giving each other a fist bump as we glided into the shallows.

• • •

SINGAPORE WAS A SHOCK after three months in Indonesia. It was so orderly, rich, and clean. Sharon, when we met at the airport, was shocked by how aggressive Bryan and I were with cabdrivers and street porters. I tried to explain that we were suffering from post-Indonesia stress syndrome, and didn’t know how to act around people who weren’t trying to haggle us into the ground. It was true, but she seemed unconvinced.

Our hotel room was air-conditioned. Sharon had brought an old-fashioned nightgown, elaborate, white, with a Victorian number of small buttons down the front. The gown could be simply thrown off upward, but the buttons were genius.

Bryan went to Hong Kong to see friends, and we stole off to Ko Samui, an island in the Gulf of Thailand, where we stayed in a bungalow on the beach. It was quiet, lovely, Buddhist, cheap. (Later, I heard, hundreds of hotels got built there. At the time it was just fishermen and coconut farmers.) There were no waves, no electricity, good snorkeling. Sharon, fresh from Northern California, seemed a bit dazed by rural Southeast Asia—the ferocious heat, implacable insects, the lack of creature comforts. And yet she was in high spirits: relieved to have finished her doctorate, happy to have flown the academic coop. When we first met, she had been a Chaucer specialist, but she had ended up writing a dissertation on the samurai figure in recent American fiction. “The latitudes of tolerance are immense,” she liked to say, quoting Philip K. Dick—referring here to her flexible dissertation advisers, there to arcane sexual practice, and most often to a general philosophical effort to comprehend the unfamiliar. She had deep reserves of adaptability herself, and a kind of romantic interest in preindustrial life that I knew well, although in me, I realized, it had faded. I was glad, and very grateful, she had come. She announced that she was keen to go to the hill country in northern Thailand, and to Burma—Rangoon, Mandalay—and she said yes to Sumatra and Nias. Her skin began to lose its fogbound pallor. Her laugh kicked back in—that high-low laugh, with its throaty, theatrical ending that drew you in.

I felt somewhat lost, truth be known. After Indonesia, I found the absence of hassling, the unbegrudged privacy on Ko Samui, unnerving. There was almost too much time and space in which to concentrate on each other. I was accustomed—deeply accustomed, by that point—to a different type of companionship. Also to constantly chasing waves, or at least slogging toward them. So this was my new life. We were both being careful—if anything, too polite. But we had brought a bottle of whiskey from Singapore, and when we broke that open we got more reckless. I had changed, apparently, become leaner and darker, and not just physically. I was more measured, even reserved, which Sharon found discomfiting. She, meanwhile, made pronouncements I found annoying. “These people have a very special love for children,” she said one day, watching a family pass down a dirt track. It was a sweet, or at least an innocuous, thing to say, but it gave me heartburn. She seemed to mean the Thai people—all forty-six million of them, perhaps three of whom she had met. It was just a style problem, I told myself. I had been speaking a different language—more cutting, ironic, masculine, permanently on guard against sounding silly—for a long time. I was fluent in that dialect, which had its lecherous crudities. I just needed to learn, or relearn, a new shared language. Sharon demanded to know why I got so particular with her—“hypercritical” might have been the word she wanted—after she had a few drinks. Was I so intolerant with Bryan when he got tipsy? The answer was no. So I bit my tongue when I had mean thoughts. It didn’t help that I was feeling vaguely unwell. I had been felled briefly in Singapore by another fever, which a doctor had said was malaria. It must have been a mild case, I figured, when the symptoms passed. Sharon urged me to eat more rice and noodles. I was all ropy muscle. A body needed some fat reserves. And it was lovely, I realized, to have somebody looking after me, looking at me, like that.

We headed to Bangkok, where we reconvened with Bryan, staying in a big, seedy place called the Station Hotel. The city was hot, chaotic, exciting, exhausting, with bright river taxis racing up and down the canals, stunning Buddhist temples, great street satay, and a rather European-looking palace. An impressive amount of drug consumption and petty drug trafficking seemed to be taking place at our hotel, among both Westerners and Asians. The presence of multiple criminal underworlds was palpable in certain quarters of Bangkok. I had a couple of assignments from Tracks—pieces about Indonesia beyond Bali—and I worked on those. Bryan’s byline would also be on them—Australian youth expected no less—after he gave my copy a light edit. But the fees would be meager, whenever they found us, and I was increasingly worried about money. With an income tax refund received, incredibly, from that worker’s paradise, Australia, I had just over a thousand dollars. Sharon had less than that. A cherubic German hustler in Sibolga, Sumatra, had offered to buy all my traveler’s checks for sixty cents on the dollar—all I had to do, he said, was report them stolen and I would get a complete refund—and I now wished I had thought more seriously about doing it. The Station Hotel had more Asia Trail hustlers per square foot than any place we’d been. Maybe I could sell my traveler’s checks here. Bryan and Sharon both rejected the idea. It was risky and wrong and I would be out of my league. All true, of course. But our stints as illegal alien laborers in Oz had worked out well, had they not?

The news was full of a humanitarian crisis on the Thai-Cambodian border. The Vietnamese army had driven the Khmer Rouge from power early that year, and a large number of refugees had been driven over the border. The Khmer Rouge had gone back to the bush and had forces in the same area, fighting the Vietnamese and increasing the general misery. I found myself poring over maps and news stories, wondering what it would take to get down there as a relief-agency volunteer. It was only a day’s drive away. Two young Frenchwomen I met at a café were going. One was a photojournalist, the other a nurse. There would be no money in it for me, and I hadn’t broached the idea yet with Sharon, but she had read Robert Stone’s Dog Soldiers—indeed, it was in her dissertation. The literary action was in Vietnam, or at least in its endlesss aftershocks. Amid this scheming and war dreaming, I made up my mind and went to the local American Express office, where I reported that I’d lost my traveler’s checks. The clerk who took my false report seemed skeptical, causing my mouth to go dry with fear, but the German hustler turned out to be right. I had a full refund in a day or two. Still, I had no idea what to do with the original checks, which were now hot goods. Defrauding American Express apparently seemed to me a fine, Robin Hood–ish thing to do. I was sticking it to a corporation that normally stuck it to everyone else. Indeed, it seemed wimpy compared with the derring-do of some of my literary idols. Dean Moriarty stole cars for kicks. William Burroughs! Bryan and Sharon were unimpressed when I told them about my caper. They suggested I flush the old checks down a toilet if I didn’t want to end up in a Bangkok jail.

All this went away the following night, in any event, when I ended up instead in a Bangkok hospital. It was an excellent little garden hospital, the best my friends could find. My memory of that night, and of the subsequent days, is watery and dim. I know I developed a high fever, began to rave, and was too weak to walk across a hotel room, let alone resist the decision to hospitalize me. I know I was horrified by the fanciness of the place they took me to—it was a clinic for foreign diplomats, apparently—but was told firmly to shut up. The doctor was German. She said that my blood was “black with malaria” and that I should be flown immediately to the United States. At that point, my friends hesitated. I was able to make my absolute opposition to such a drastic measure understood, and they were reluctant to overrule me. There was discussion of my survival chances, and of all the malaria cases the doctor had seen in forty years in Asia. They did not put me on a plane.

Dark days ensued. Wild, aching fevers turned into rattling, arctic chills. I lost a startling amount of weight, bottoming out at 135 pounds. (I’m six foot two.) The old doctor—her name was Dr. Ettinger—was severe but kind. She said that I was a lucky boy and would survive. Small nurses gave me big shots in both hips. I was so listless that I did not leave my bed for a week. Paranoia and depression annexed my brain. I couldn’t bear to think about the unpayable bill that was mounting up. Bryan and Sharon came daily and entertained me with stories from the Bangkok beyond the quiet lawns and hedges I could see. But it was hard for me to laugh or smile. I felt lost, spiritually, and the growing suspicion that I was wasting my life came back with a vengeance. I wished my father would appear and give me some concrete, comprehensive advice. I would follow it to the letter. Not that I wanted my parents to know I was ill. And they didn’t know.

Then Bryan stopped coming to visit. Sharon was vague about his reasons. He was meeting with some people. I decided that the two of them were sleeping together. I went over in my mind, many times, an incident at the Station Hotel. Bryan had been sitting in our room. Sharon was taking a shower. She had strolled out of the bathroom naked, and Bryan had bellowed and covered his eyes. She laughed and called him a prude, while he groaned and begged her to put something on and kept his eyes covered. At the time, I had thought it was funny. She knew she looked great nude, and she got a kick out of shocking him. They were good friends and she knew that under his macho bawdiness was a certain primness and a strict sense of boundaries. So she enjoyed teasing him. That was all. There was no sexual tension between them, I thought.

But maybe I was wrong. Or maybe she was having her revenge on me for being a selfish jerk, leaving her hanging forever while I chased waves. Once, exasperated by my travels with Bryan, she had shocked me by saying, “Why don’t you two just fuck each other and get it over with?” It was so off the mark and, in its fatuous literalism, not like her. But how well did I really know her? How well, for that matter, did I know him? I had never told him she said that, but I could imagine his reply if I had—“Right on, Tom.” It was his go-to quip, which I alone understood, when the subject was male homosexuality. But I had misjudged my friends before, and had been sexually betrayed.

The nights were the worst. I felt trapped in a tropical version of Goya’s Pinturas Negras. Ghouls seemed to surround my bed, their shadows on the walls. My headache filled the world. I couldn’t sleep. I knew, rationally, that Bryan and Sharon had done the right thing by bringing me here. They had probably saved my life. I was getting good care. But the bill was now so far beyond my means, I would be lucky if they—and did that mean the hospital? the U.S. embassy?—let me buy an air ticket home. I would return to the States in disgrace—penniless, my health broken, a failure.

Late one night, long after visiting hours, Bryan showed up at my bedside. He was carrying a large shopping bag. He didn’t say a word. He turned the bag upside down and dumped its contents—many fat, dirty bundles of Thai baht, the local currency—on my lap. It was a lot of money. It would be enough to cover most, if not all, of my hospital bill, he said. He looked exhausted, triumphant, angry, a bit crazed.

I never got the full story, but I got the gist from Sharon. Bryan, seeing that my situation was desperate, had looked through my bags in our room and found the checks I had reported lost. (I had long forgotten, in my delirium, that they existed.) Then he had gone out and sold them, for sixty cents on the dollar, to Chinese gangsters. It had not been a straightforward transaction. He had refused to hand over the goods until he had payment in full in hand. The whole thing had taken days, and had turned into the haggle to end all haggles. It was all totally unlike Bryan, from beginning to end, and yet he had prevailed. For the two of us, it was a full role reversal. He took a huge risk, freed me from the hospital, and in the process freed himself from me.

• • •

SHARON AND I did make it to Nias eventually. It was monsoon season by then, though, and the rains messed up the waves. There were also fifteen surfers in Lagundri, and the reason why was presented to me on arrival: a ravishing photo of the ravishing wave had appeared in an American surf magazine. The era of semisecrecy was over. Fifteen guys would soon be fifty guys. Many people in the village, including children, seemed to be sick. It was endemic malaria, the losmen owners said. People begging for random medicines was even less funny now. I was taking a new prophylaxis for malaria—two, in fact—and still hobbling from the big injections the little nurses had given me months before in Bangkok. There were a few days of good waves. I found I had regained enough strength to surf. The volleyball, guestbook, and watch were graciously received. But these little tokens of exchange now felt, to me, gruesomely beside the point.

We pushed on, always edging west. We caught a ship from Malaysia to India, sleeping out on the deck. We rented a little house in the jungle in southwest Sri Lanka, paying twenty-nine dollars a month. Sharon was ostensibly quarrying articles from her dissertation. I resumed work on my novel. We got Chinese bicycles, and each morning I rode mine, board under arm, down a trail to the beach, where a decent wave broke most days. We had no electricity and drew our water from a well. Monkeys stole unguarded fruit. Sharon learned to make delectable curry from our landlady, Chandima. A madwoman lived across the way. She roared and howled day and night. The insects—mosquitoes, ants, centipedes, flies—were relentless. At a Buddhist monastery down the hill, young monks held rowdy parties, blasting taped music and banging on cowbells till dawn. I heard a lot of anti-Tamil talk—we were living in a Sinhalese district—but this was before the civil war.

I wonder now if Sharon had any interest in my grand travel plan, or if she even knew what it was. It was corny, so I never mentioned it, my ambition to go, without too many shortcuts, around the world. I remember, back on the morning I left Missoula, telling a friend there. We were standing on the sidewalk, surrounded by dim snowy mountains, outside the café where she worked. That day, I said, I was heading west, to the coast. When I came back—pause for hokey effect—it would be from the east. She cocked her head and laughed and dared me to do it.

Sharon was interested in Africa, so our notions were still in step. We kept going west. We looked for a ship to Kenya or Tanzania, but both countries required visas that weren’t available in Sri Lanka. We ended up flying to South Africa. In Johannesburg we bought an old station wagon and made our way to the coast at Durban. We car-camped down through Natal and the Transkei to Cape Town. I surfed. This was 1980, still the heyday of apartheid. I continued to do my informal interviews of randomly encountered people. Here those yielded great hauls of weirdness: inscrutable evasions from polite black workers and country folk; the most relaxed and profound racism from white fellow campers. Sharon and I were on a steep learning curve, reading Gordimer, Coetzee, Fugard, Breytenbach, Brinks—their unbanned work, anyway. Every surfer was white, which was no great surprise. For the next leg of our rambles, we had a bold idea: a huge tack to the north, “Cape to Cairo,” overland. But we were running out of money.

In Cape Town we heard that the local black schools suffered from a perennial shortage of teachers, and that the academic year was just beginning. Someone gave me a list of township schools. At the second school I visited, Grassy Park Senior Secondary, the principal, a blustery fellow named George Van den Heever, hired me on the spot. I would teach English, geography, and something called religious instruction, starting immediately. My students, who wore uniforms and ranged in age from twelve to twenty-three, seemed gobsmacked to find a clueless white American standing in their classroom, wearing brown plastic loafers from Sri Lanka and a three-dollar striped tie bought that morning at Woolworth’s, but they swallowed their doubts and called me “sir” and were for the most part helpful and kind.

Sharon and I rented a room in a damp old turquoise house overlooking False Bay, on the Indian Ocean side of the Cape of Good Hope. The Cape Peninsula is a long, spindly finger pointing south at Antarctica. At the peninsula’s base—its north end—sits a spectacular high massif, and the city of Cape Town wraps itself around that. The north face of the massif is Table Mountain, which overlooks the city center. The black people of Cape Town had been banished en masse from the city to a scrubby wasteland to the east called the Cape Flats—one of apartheid’s signature acts of rabid and remorseless social engineering. Grassy Park was a “coloured” township on the Flats—a poor, crime-ridden community, and yet far less wretched than some of the shantytowns that surrounded it. We lived, by law, in a “white area.” Since Grassy Park was only a few miles from the False Bay coast, my commute actually wasn’t bad. Out in front of our dank mansion, there was a wide, shapeless beachbreak, which I surfed when I wasn’t too busy grading papers or planning lessons.

My job became all-consuming. Sharon considered teaching too, but she had paperwork problems with the bureaucracy. Then word came that her mother was seriously ill. She threw her things in a bag and flew to Los Angeles. I muttered about going with her, but I didn’t seriously consider it. It had been a year since she came to Singapore. We had found a good rhythm together—our curiosities overlapped; we rarely quarreled. But I had projects: a novel, a circumnavigation, places I wanted to surf, and, now, teaching in Grassy Park. Sharon’s goals were less immediate, less evident. With my usual one-eyed thoughtlessness, I never asked her what she wanted. We never talked about the future. She was nearly thirty-five. The truth was, we were mismatched. I had somehow kept her interested for years, but I wasn’t what she wanted. Meanwhile, I took her for granted. We made no plans or vows when she left Cape Town.

• • •

ONE OF THE REASONS teaching became so engrossing was that it was impossible to teach using the textbooks we were given. They were rank with apartheid propaganda and misinformation. The geography curriculum, for instance, included a section on South Africa’s neighbors that depicted them as peaceful Portuguese colonies. Even I knew that, in fact, Mozambique and Angola had both fought long, bloody wars of national liberation, had thrown out the Portuguese some years before, and were both now fighting desperate civil wars in which South Africa was arming and training the rebels. Our curriculum’s version of South African urban geography was, in its way, worse. It treated residential racial segregation, for instance, as if it were a law of nature, peacefully evolved. Presenting this regime-serving fiction as fact in a community that existed only because of violent mass evictions from downtown neighborhoods designated “white” was clearly not on. So I buried myself in research, trying to quickly learn up these and other topics, which turned out to be harder than expected. Many of the relevant books were banned. I found my way to a special section of the University of Cape Town’s library where some banned publications could be consulted, not checked out, but I was still, of course, playing hapless catch-up when it came to local and regional politics and history.

Not that my students seemed particularly concerned about my expertise or lack thereof. They nearly all declined to be brought out on political subjects—whether from indifference or wariness of me, I couldn’t tell. The exceptions were among the seniors I saw, ostensibly for religious instruction. At their insistence, we never cracked the Bibles that were our sole textbooks, but passed our class time in free-ranging discussion. Their favorite topics were careers, computers, and the pros and cons of premarital sex. Among the seniors not averse to talking politics was a brooding, worldly boy named Cecil Prinsloo. He knew somehow about my efforts to teach my academic classes something other than the government syllabus. He started staying after class to talk, questioning me closely about my background and views, testing my feeble grasp of the situation in South Africa. The only real resistance to my efforts to end-run the syllabus came not from my students but from my more conservative colleagues. They too had heard that I wasn’t simply preparing my classes for the standard examinations they would eventually face, and they let me know that this was unacceptable. I couldn’t see what to do. Luckily, none of my students in the exam subjects I taught were facing standardized national exams that year. Those were another year or two away for them. So my abandoning the toxic syllabus wasn’t putting them in immediate academic peril. I tried to reconcile myself to the good chance that I would soon be fired. I had no job security—just the principal’s goodwill. And the principal was quite conservative himself. But I really, really didn’t want to stop teaching.

Some of my students, Grassy Park High School, Cape Town, 1980

Everything changed one April morning when our students suddenly started boycotting their classes, protesting apartheid in education. I say it was sudden because it stunned me. In truth, the boycott had been long and carefully planned. The school was plastered with banners: DOWN WITH GUTTER EDUCATION; RELEASE ALL POLITICAL PRISONERS. The students were marching, singing, fists raised, roaring the Zulu call-and-response of the liberation struggle:

“Amandla!” (Power!)

“NGAWETHU!” (To the people!)

At a mass meeting in the school courtyard, Cecil Prinsloo told the crowd, “This is not a holiday from school.” He emphasized every word. “This is a holiday from brainwashing.”

Other Cape Flats high schools were also boycotting, and the protest quickly went national. Within weeks, two hundred thousand students were refusing their lessons, demanding an end to apartheid. At Grassy Park High, the students continued to come to school each day, organizing, with the help of sympathetic teachers, an alternate curriculum. I was among the sympathetic teachers. With revolution-minded students now in charge, my previous deviations from the syllabus no longer seemed like derelictions, and I stopped fearing for my job. My classes on the U.S. Bill of Rights were packed. It was a chaotic, exhilarating period.

But the exhilaration was short-lived—a matter of a few weeks. The authorities had been wrongfooted. The prime minister, P. W. Botha, blustered and threatened, but the state’s enormous machinery of repression seemed slow to lurch into gear. Once it did, however, the atmosphere darkened fast. Student leaders, including some from our school, and revolution-minded teachers, including my colleague Matthew Cloete, who taught in the classroom next to mine, began to disappear—some into hiding, most into the regime’s jails. It was called detention without charges, and the number of known detainees quickly soared into the hundreds.

The confrontation escalated. In Cape Town it climaxed in a general strike in mid-June. For two days, hundreds of thousands of black workers stayed home. Factories and businesses were forced to close. The police, now armored and fully mobilized, attacked illegal gatherings—and all gatherings of black people were effectively illegal now, under something called the Riotous Assemblies Act. Burning and looting began, and the police announced that they would “shoot to kill.” The Cape Flats became a battlefield. Hospitals reported hundreds of maimed and injured. The press reported forty-two dead. Many of the dead and injured were children. The schools were all closed now, along with all the roads into Grassy Park. Information was hard to come by. When the roads reopened, I drove to Grassy Park. The destruction in some areas of the Flats was extensive, but our school was fine. I found three of my students. They said that they had stayed inside their houses throughout the violence. It seemed that none of our students had been hurt, which felt like a miracle.

Three weeks later, classes resumed. We were only halfway through the school year and, as the principal kept reminding us, there was a great deal of extra work to do now.

• • •

DID I SURF while my world abruptly compacted into a township high school and a few dozen teenagers there? Some. There were good waves on the Atlantic side of the Cape, where the water was surprisingly cold—my parents sent me my wetsuit. Heavy swells rolled in from the Southern Ocean as winter commenced. Most of the better spots were in rocky coves, some of them right in the city, hard by swanky apartment blocks. Others were farther down the mountainous, windswept Cape. My favorite spot was a quiet country righthander called Noordhoek. It broke at the north end of a magnificent sweep of empty beach: an A-framed peak with a lovely inside wall, good on southeast winds. The water was often a luminous blue-green. I sometimes surfed it completely alone. One afternoon I climbed the hill back to my car and found it full of baboons. I had left a window open. The monkeys had made themselves comfortable and did not scare easily. I ended up having to use my board as épée, club, and shield when they staged frightening mock attacks, teeth bared, before ambling off.

The place I was waiting on, though, was in the Eastern Cape, some four hundred miles up the Indian Ocean coast from Cape Town. It was called Jeffreys Bay, and no circumnavigation on a surfboard would be complete without a stop there. The Endless Summer, a 1964 film that warped the career goals of many young surfers, including me, climaxed near Jeffreys, when two American surfers found “the perfect wave” at Cape St. Francis. The spot featured in the film turned out to be a fickle creature, not often ridable, but Jeffreys Bay was the real thing: a long right point of the highest quality, with heaps of swell in the winter and frequent offshore winds. I tried to keep my eye on conditions, and I made a couple of quick trial runs from Cape Town without catching it especially good. Then, in August, I went for a week on a promising weather map: two big low-pressure spirals in the Roaring Forties. They looked like wave-generating storms spinning right in the window for Jeffreys.

And they were. The surf pumped all week, peaking on a day so big that only one guy made it out—a number of us tried and failed—and he caught only one wave. Jeffreys Bay was a tiny, tumbledown fishing village with a few stucco summer houses scattered through the aloes. I stayed in a weatherbeaten boardinghouse in the dunes east of the village. There were four or five Australians also staying there, and it was comforting, I found, to be back in the easy company of Aussie surfers. The great wave was just down the beach, farther east. There were few people around—rarely more than ten surfers in the water—and with the size of the waves and the length of the rides we were generally scattered up and down the point. On a couple of mornings I was the first one out, slipping through a keyhole that I’d seen the locals use near the top of the point. There was often an icy offshore wind, and at sunrise the waves approached out of a blinding sea. As soon as you caught one, though, the wave threw a deep green-and-silver shadow inside which, as you rose to your feet, everything became radiantly clear.

It was an astoundingly long ride. Longer even than Tavarua. And it was a right—on my frontside. The two spots are not actually similar. Jeffreys is rocky but not especially shallow. It’s a facey wave, a broad canvas for sweeping long-radius turns, including cutbacks toward the hook. It’s fast and it’s powerful but it’s not particularly hollow—it has no bone-crushing sections à la Kirra. Some waves have flat sections, or weird bumps, or go mushy; others close out. The rule, however, is a reeling wall, peeling continuously for hundreds of yards. My pale blue New Zealand pintail loved that wave. Even at double-overhead, dropping in against the wind, it never skittered. Some of the biggest sets that week nobody wanted, at least not out at the main takeoff spot, where the walls on the big days were massive and intimidating. You want it? No, you go! And the moment would pass, the beast unridden. Farther down the line, at a less scary juncture, somebody might jump aboard. These were the best waves I had ridden since our first trip to Nias, more than a year before. It was different, surfing in a wetsuit, and the famous Jeffreys was nothing like the equatorial obscurity of Lagundri, but technically it was as if my board and I picked up almost exactly where we had left off. Big right wall, power over the ledge, jump up, pick a line, pump for speed, run and gun. Try to keep from screaming from joy.

In the evenings we threw darts, played snooker, drank beer, talked surf. The owner of the guesthouse was an older man, a British colonial blowhard who had been chased south from East Africa by decolonization. He liked his gin and loved to boast about all the Africans he had “taken down from the tree” and taught some useful skill—boot polishing or how to use a broom. I couldn’t listen to him. The Aussies didn’t mind him, though, which reminded me of my least favorite thing about Australia. In the casino kitchen where I had worked, the other dixie bashers all talked disdainfully of “wogs,” a vast category of humanity that included southern Europeans. Refugees were pouring out of Southeast Asia then—“boat people”—and the caustic racism that suffused the subject in nearly every discussion I heard in Oz was startling.

As things turned out, I made it back to Jeffreys the following winter—1981—and caught it good again. By then, I had been in South Africa eighteen months—far longer than I had ever expected to be. And yet I never found anyone in South Africa to surf with. I got to know surfers in Cape Town, but their familiar obsession with scoring waves felt, under the apartheid circumstances, vaguely embarrassing, almost ignominious. I had no right to judge how South Africans, black or white, dealt individually with their extraordinary situation, but working on the Cape Flats, seeing the workings of institutionalized injustice and state terror up relatively close, was deeply affecting me—was making me impatient with, among other things, myself. There was simply no escaping politics, and I found no common political ground with any of the surfers I met. So I chased waves alone.

• • •

MY PARENTS CAME TO CAPE TOWN, on short notice, uninvited. I didn’t want them to come. I was exceptionally busy at school, but it wasn’t that. I was homesick, chronically, particularly now that Sharon was gone, and I was worried that seeing my mother and father—seeing their faces, hearing their voices, particularly my mother’s laugh—would shatter my resolve to stay on this lonely expat track and complete my chosen projects: teaching, the novel.

It was also the cognitive dissonance between the world I was living in now and what I imagined to be their world. Not that I had anything like a clear view of their lives. They wrote letters faithfully, and I did too. So I knew the outlines, even the details, of my family’s projects, mishaps, interests. My siblings were in college now, and they also wrote. But my parents’ reports of movies made, vacations taken, sailboats bought, seemed to arrive from a particularly distant planet. My father had been on the ropes, professionally, a few years before. He and my mother had started their own production company, and then had shows canceled, deals fall through, financing vanish. I only understood how bad it was when I discovered that they were attending trendy neo-Buddhist “est” seminars offered by an authoritarian charlatan named Werner Erhard, who briefly charmed much of Hollywood. This discovery had frightened and, I am ashamed to say, disgusted me. It suggested desperation and seemed so egregiously L.A. (Actually, “est” was popular in New York, Israel, San Francisco, and many other places—even white Cape Town!) My parents’ New Age nadir now seemed to have occurred very long ago, though. In the intervening years, their company had prospered, their horizons widened. They were making pictures they were proud of, working with people they liked. This was all to the good, of course. The problem was, I had been gone so long, their lives now sounded very glossy and foreign, while my life in Cape Town was so funky and modest. I was not ready for some spiffed-up jet-set version of my parents to come crashing into my humble schoolteacher’s daily slog. They understood that, I’m sure. But enough was enough—it had been two and a half years—and I didn’t have the heart to ask them to stay away.

That was lucky. It was unambivalently terrific to see them. And they seemed elated to see me. My mother kept grabbing my hand and kneading it between hers. They both seemed younger, more bright-eyed and spry, than I remembered them—and there was nothing spiffed-up about them. I showed them around the Cape. They seemed fascinated by every Cape Dutch gable and WHITE PERSONS ONLY sign, every shantytown and vineyard. I was living at that point in a room near the university, on the eastern slopes of Table Mountain. With two of my housemates, we climbed the mountain—not a small hike—and picnicked on top. From up there, we could see, out in Table Bay, Robben Island, where Nelson Mandela and his comrades were imprisoned but not forgotten. (Their words and images were strictly banned.) Then we descended the western slopes to the coast.

My folks insisted on visiting Grassy Park High. My students double-insisted that I bring them. And so we went, on a day that I had taken off. The principal was an enthusiastic host—he loved Americans. He took my parents on a campus tour, and I made sure that we stopped in on my students, whose schedules moved them always in a group. Each time we entered a classroom, they all sprang to their feet, staring, bellowing, “Good afternoon, Mr. and Mrs. Finnegan.” I didn’t know what to do, so I introduced them individually, running up and down the rows—Amy, Jasmine, Marius, Philip, Desiree, Myron, Natalie, Oscar, Mareldia, Shaun—eliciting grins and blushes as I went. After five or six classes of this, the principal claimed he had never seen such a prodigious feat of memory, but it actually was effortless and, I realized, an easy way to show my parents, without belaboring it, the extent of my involvement with these kids. My own classroom, New Room 16, had been taken over by a group of senior girls who had prepared a banquet. There was a huge pot of curry, and a great array of Cape Malay specialties: bredie, samoosas, sosaties, frikkadels, yellow rice with raisins and cinnamon, roast chicken, bobotie, buriyani. School had let out by then, and the other teachers were invited. June Charles, my youngest colleague—she was only eighteen yet teaching high school—guided my father through the strange and tasty dishes. My mother, meanwhile, hit it off especially with a math teacher, Brian Dublin, and complimented him more than she knew when she said that with his beret and his beard he reminded her of Che Guevara. Brian was an activist whose seriousness and dedication I had come to admire.

My parents, it occurred to me, were proud of me. Okay, it wasn’t the Peace Corps—my mother’s early ambition for me—and it certainly wasn’t Nader’s Raiders. But I had become their son-who-was-helping-oppressed-black-kids-in-South-Africa, which was not bad. They were particularly taken with an ad hoc career-counseling project I had started, which they heard all about from my biggest fan, the principal. The project had grown from my first conversations with seniors, who were full of big career dreams but seemed to have almost no information about colleges and scholarships. We had written to universities and technical schools all over South Africa and received armloads of booklets, brochures, and applications, including a great deal of encouraging news about financial aid and “permits” that would allow black students to attend formerly all-white institutions. The material eventually filled a whole shelf in the library, and proved to be popular reading, and not only among seniors. With the seniors, I had worked out applications plans and strategies that seemed to me quite promising. What I didn’t know was that the “permits” we needed were fiercely controversial in the black community and had become, indeed, the object of a liberation-movement boycott—nobody could bring themselves to tell me. Actually, what I didn’t know was far more than that. Very few of our seniors, for instance, would ultimately qualify after their final exams for entrance to most of the universities we were interested in, including the University of Cape Town. There were already, of course, existing networks, invisible to me, for graduating seniors to make their way into the worlds of work or further study. In the end, I came to see my careers program as an enormous American folly, even in some cases quite destructive, where it encouraged false hopes or encouraged kids to defy boycotts that I knew nothing about.

But my parents, who were even more clueless than I was, thought my work looked grand. Which felt great, in a rueful sort of way.

• • •

THE REMEDIATION of my cluelessness—my ground-level education in progressive South African politics—came largely from activists like Brian Dublin, Cecil Prinsloo, and others who eventually decided to trust me. My main interlocutor turned out to be a senior from another high school. Her name was Mandy Sanger. She was a friend of Cecil’s, and she had been one of the regional boycott leaders. She took special pleasure in puncturing what she considered self-serving liberal illusions. As the school year wound down, and I saw nothing—after the ragged and violent end of the great student boycott—but discouragement and retrenchment for what everybody called the Struggle, Mandy set me straight about lessons learned, commitments deepened, and national organizations strengthened. “This year was a big step forward, and not only for students,” she said. She was only eighteen, but she had the long view.

There was no graduation ceremony, no end-of-year ritual. My students drifted away after their exams, wishing me happy holidays, hoping to see me next year. I wasn’t going to teach another year, though. I had saved enough to resume, on the super-cheap, my travels—but only after I finally finished, I decided, my poor old railroad novel. Before I buckled down to that, I planned to spend Christmas in Johannesburg with friends. My ancient car wasn’t up to the long drive, so I would hitchhike. To my surprise, Mandy asked to come along. It seemed that she had business, unstated, in Johannesburg. I didn’t see how I could say no. The trip took us several days. We dodged cops, slept out in the veld, squabbled, laughed, got burnt by the sun, chapped by the wind, and met a wild miscellany of South Africans. After Christmas, we hitchhiked to Durban, where Mandy had more student-activist business, again unstated. The phones, the mail were no good—the Special Branch, as it was called, tapped phones and opened mail. Resistance activists needed to meet face-to-face. After Durban, we hitchhiked down the coast. In the Transkei, we camped on the beach. I borrowed a surfboard and pushed Mandy into gentle waves. She cursed nonstop. But she was athletic, and she was soon popping to her feet unassisted.

Mandy was interested in my plans—whether I would just keep traveling around forever. Not a chance, I said. I would soon head back to the United States. But I asked her advice. Did she think there was anything useful that I could write for American readers about the situation in South Africa? She had, I knew, a hardheaded, utilitarian view of what foreigners could do to help the Struggle, and I had taken on enough of that view myself that the idea of entertaining my compatriots with appalling tales of “apartheid” now felt inadequate, or worse. Obviously, my readers would do nothing. The cause would not be advanced. Maybe I would do better just to write about—hell, something I actually knew about. Surfing. We debated this question intermittently on our long looping hitchhike from Cape Town to Cape Town. Mandy complained that I had complicated her view of America, which she normally thought of as a capitalist ogre hell-bent on destroying progressive movements around the world, with my stories of the brakeman’s life on the railroad in California. Then, on a sun-drenched point in the Transkei, watching Xhosa fishermen pull in galjoen with bamboo poles, she encouraged me to return to the United States and figure out there what I could usefully write. I could probably write about subjects other than surfing. “And I say that as one surfer to another!”

• • •