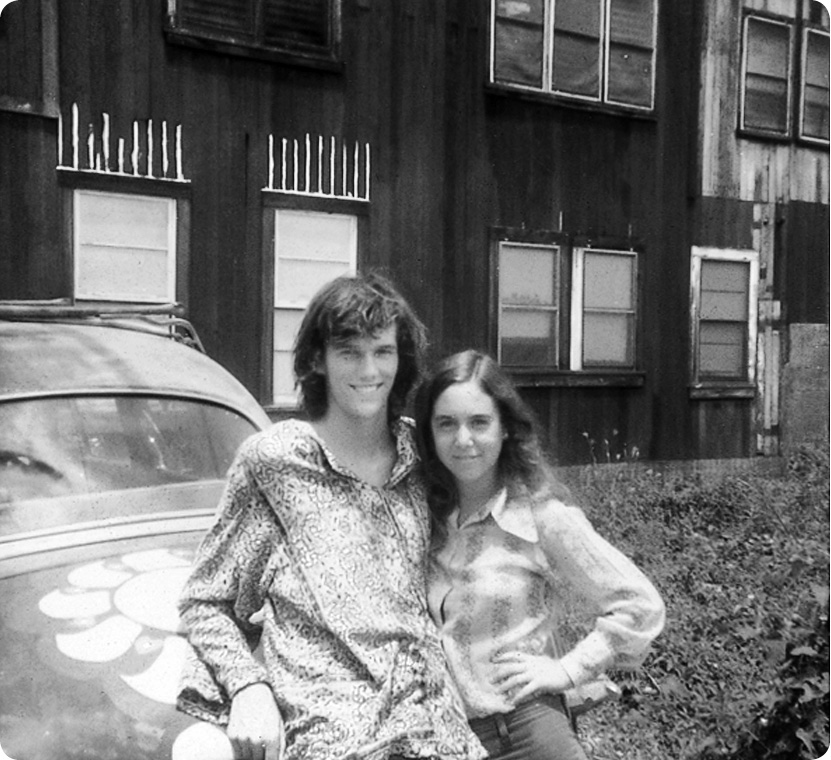

With Caryn Davidson, in front of Kobatake’s rooming house, Lahaina, 1971

FOUR

’SCUSE ME WHILE I KISS THE SKY

Maui, 1971

“YOU KNOW WHAT YOUR PROBLEM IS? YOU DON’T LIKE YOUR OWN kind.”

This blunt assessment of me came from Domenic in 1971. Our respective politics, it seemed, were diverging. We were eighteen. It was springtime. We were camping on a headland at the west end of Maui, sleeping in a grassy basin under an outcrop of lava rocks. A little pandanus grove helped block the view of our campsite from the pineapple fields up on the terrace. This was private property, and we didn’t want the farmworkers to spot us. We were raiding their fields at night, trying to find ripe fruit they had missed. We always seemed to be camping on somebody else’s property in those days. Here, we were waiting for a wave.

It was late in the season, but not too late for Honolua Bay to break. That was our hope at least. Every morning at first light we would stare out across the Pailolo Channel, toward Molokai, trying to will the north swells to appear, their dark lines latticing the warm gray waters. It felt like something was stirring, but that could have been wishfulness on our part. After sunrise, we hiked around the point into the bay, studying the shorebreak against the red cliffs. Did it seem stronger than yesterday’s?

Our lives, Domenic’s and mine, had been like an unraveling braid for the past couple of years. The proximate cause of our disengagement was a girl: Caryn, my first serious girlfriend. She and I had found each other as high school seniors. My plans to bum around Europe with Domenic after high school became plans to bum around Europe with Caryn. We all ended up going, but we didn’t see each other over there as much as we had planned. Then I went back to start college, at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and Caryn came with me. Domenic stayed on in Italy, living with relatives in the village where his father was born, in the eastern Appenines, working in a vineyard, learning Italian. (Domenic liked his own kind fine. I envied that.)

Now Domenic was living, for reasons that undoubtedly made sense then, in a converted milk truck at a beach park on Oahu—scraping by on odd jobs in paradise. I was on my freshman spring break, and my family was living in Honolulu again, so Domenic and I had reconvened there. Both of us had, like everyone who grew up on surf mags, dreamed since childhood of surfing Honolua Bay. But it was odd, in a way, that we were here, waiting on waves, since we had both quit surfing years before.

It happened when I turned sixteen. It wasn’t a clean break, or even a conscious decision. I just let other things get in the way: car, money to keep car running, jobs to make money to keep car running. The same thing happened with Domenic. I got a job pumping gas at a Gulf station on Ventura Boulevard, in Woodland Hills, for an irascible Iranian named Nasir. It was the first job I had that wasn’t devoted exclusively to the purpose of paying for a surfboard. Domenic also worked for Nasir. We both got old Ford Econoline vans, surf vehicles par excellence, but we rarely had time to surf. Then we both fell under the spell of Jack Kerouac and decided we needed to see America coast-to-coast. I got a job working graveyard shifts—more hours, more money—at a grubby little twenty-four-hour station on a rough corner out in the flatlands of the San Fernando Valley. It was a place where Chicano low riders would try to steal gas at 5 a.m.—Hey, let’s rip off the little gringo. I got a second job parking cars at a restaurant, taking “whites” (some kind of speed—ten pills for a dollar) to stay awake. The restaurant’s patrons were suburban mobsters, good tippers, but my boss was a Chinese guy who thought we should stand at attention between customers. He badgered and finally fired me for reading and slouching. Domenic was also stacking up money. When the school year ended, we pooled our savings, quit our gas station jobs, said good-bye (I assume) to our parents, and set off, zigzagging east, in Domenic’s van. We were sixteen, and we didn’t even take our boards.

We got as far south as Mazatlán, as far east as Cape Cod. We dropped acid in New York City. We subsisted on Cream of Wheat, cooked on a Coleman camping stove. It was 1969, the summer of Woodstock, but the flyers for the festival plastered around Greenwich Village mentioned an admission charge. That sounded lame to us—some kind of artsy-craftsy weekend for old people—so we skipped it. (My newsman’s intuition, never great, was then unborn.) I kept uninteresting journals. Domenic, a nascent photographer, was in his Walker Evans period, shooting white street kids in South Philly, runaway girls asleep on the banks of the Mississippi. Years later, Domenic’s first wife, a worldly Frenchwoman, refused to believe that we slept chastely side by side all summer in that van. We did, though, and our friendship flourished in the daily onslaught of the unfamiliar. I felt less compelled to self-mock; Domenic seemed relieved to be rid of the popularity that defined him at school. We relied on each other completely; the perils and the laughs were shared. In Chicago we met a scary guy who we later decided must have been Charles Manson. I got served my first drink in a bar—it was a Tom Collins—in New Orleans. I read Edith Hamilton’s translation of The Odyssey propped on the steering wheel while driving across North Dakota. We got too close to grizzly bears in the Canadian Rockies. We surfed only twice that summer—once on borrowed boards in Mexico, and once in East Coast slop in Jacksonville Beach, Florida.

This is what I mean by quitting surfing. When you surf, as I then understood it, you live and breathe waves. You always know what the surf is doing. You cut school, lose jobs, lose girlfriends, if it’s good. Domenic and I didn’t forget how to surf—it’s like riding a bike that way, at least when you’re young. We just diversified, and I, for my part, plateaued. That is, I had been steadily improving since I started, and at fifteen, while hardly a contender, I was a little ripper. My rapid progress stopped when I got interested in the rest of the world. We didn’t surf in Europe. Santa Cruz, a beach town in Northern California, has good waves, so I had been getting in the water, but on my own schedule, not the ocean’s. The old nothing-else-truly-matters obsession was in abeyance.

• • •

HONOLUA BAY was about to change that. We didn’t hear the swell start to hit in the night because the trades were offshore, blowing the rumble of waves striking the headland’s boulders back out to sea. But Domenic, taking a piss at first light, saw the surf. “William! We got waves.” He called me William only on serious occasions, or as part of a joke. This was a serious occasion. We had run out of food the night before, and had been planning a run to Lahaina, the nearest town, which was twelve miles away, for provisions. That plan was postponed indefinitely. We scavenged for nutrients—gnawing old mango rinds, scraping out soup cans, choking down bread previously rejected as moldy. We grabbed our boards and jogged around the point, screaming “Fuck!” and hooting nervously at each gray set that passed the headland, darkening on the final turn into the bay.

We couldn’t tell how big it was, even after we got there. The bay itself was unrecognizable, at least to us, who had only seen it flat. There were waves breaking clear from the point to the cove, hundreds of yards, waves so beautiful that, as they hurled themselves into the offshores, they made me a little queasy. But this was not a classic pointbreak, in the mold of a Rincon. There were big sections, especially outside, that looked unmakable, and a rock bluff maybe fifty feet high that stuck out into the surf line, with a narrow beach that had formed just above it, at the bottom of the cliffs. There was certainly no obvious place to paddle out. Too impatient to hike all the way to the palm grove at the bottom of the bay and paddle from there, we picked our way down a steep trail to the narrow beach between the point and the bluff. The surf looked solid but not huge. The sun was still not up. We waited for a lull, dancing in the broken coral rocks rolling in the shorebreak. Then we sprint-paddled into the lines of whitewater, angling away from the point but keeping a wary eye on the bluff just downcoast.

We made it out to clear water. Slapped fully awake by the few sharp blows of whitewater received on the push-through, we paddled around in circles, trying to see the reef in the still-faint light. Where was the takeoff spot? We seemed to be straight off the big bluff, but the water depth was hard to gauge. Faint boils appeared around us as small sets rolled through, exploding against the cliffs. Then the first real set arrived. It came straight to us. Meaning: the waves, visible from half a mile off, first stood up and broke near the point, reeling but uneven, and then formed a long, unmakable wall, at the downcoast end of which was a broad, heartstopping hump—a great bowl section that feathered for a good while before it broke. And that was where we were waiting, straight off the bluff, in the middle of the big bowl section. It was the prime takeoff spot.

We each caught a wave in that first set, each pushing bug-eyed over a heaving ledge. The drop was challenging, the acceleration intense—there was a moment of unwanted weightlessness—but the faces were smooth and there was actually time, in the course of a drawn-out, skittering first bottom turn, to get a good look down the line. And the wave tapered cleanly away from the takeoff section, flawless as a nautilus shell. It was exactly what you hoped to see after such a drop. We each rode far down into the bay. The wave, as it stood up along the reef, bent sharply toward the cliff but never seemed to get any closer to it, speeding up across shallow slabs, slowing down in deeper water, then speeding up again, getting glassier and smaller all the way, though still with a light offshore plume. Domenic must have been on the second one, because I remember pulling out far inside and seeing him half crouched in a peeling, gray-blue hook, dragging one hand in the face.

Honolua Bay was, of course, a famous spot. That was why we were there. But no one else showed up, and as the sun rose we continued to surf alone. The waves weren’t big—six feet on the sets—and the swell probably wasn’t showing up yet in those populated parts of the Maui coast where the surfers lived. Forecasting surf had not become the popular, computerized science it is today—most people just got up and looked at the waves, as we had. Still, surfing a great wave like Honolua on an immaculate day with only two people out was very unusual, which made it hard to relax. For hours we windmill-paddled from the cove out to the takeoff spot, desperate not to miss a set, too tired to speak, just shouting odd imprecations. “Jesus fucking Christ!” “Murphy, Murphy!” Once we were in the lineup, if we had a lull, we might rehearse our rides and pool our research on the reef, which had some scary parts, especially as the tide began to drop.

Domenic was riding a small blue twin-fin. It seemed to love the waves. But he didn’t know the board well, and it turned out that at high speeds one of the fins began to hum. It was a homemade board, and twin-fins were a new thing, and there seemed to be an alignment problem that had not been evident in slower waves. The hum was distracting for him, and got so loud that I could hear it as he surfed past me. He didn’t think it was as funny as I did—this fly in the ointment of perfection—and he begged me to switch boards. I rode a couple of waves on the horrible hummer and gave it back. Eventually, even Domenic was laughing, trying to sing along with his underfoot zither as he rode. He always had a well-developed sense of the absurd—even, I would say, a philosophy that was anchored in a sense of imperfection, in a classical sense of the possible, and of the gods toying with us. I’ve never known where he got that.

Why did he say that thing about my not liking “my own kind” while we were camping at Honolua? He was saying lots of critical, dismissive things about me then. I had become, to be sure, an obnoxious, pretentious college student, taking a backpack full of books by R. D. Laing, Norman O. Brown, and other fashionable authors of the day even on a surf-camping trip. (I was studying literature with Brown in Santa Cruz.) I had probably just bored him with a lecture lifted from Frantz Fanon. (At least he didn’t call me a self-hating white boy.) I had certainly developed a weak spot for anticapitalist, even Third Worldist politics. All this made me an impractical egghead, as far as Domenic was concerned, and he never tired of pointing out my (real, but not exceptional) mechanical incompetence. He exulted in the contrast with his own ingenuity around engines and other contraptions. I imagine he was feeling competitive, even insecure, as I increasingly went my way and he his. Also, perhaps, hurt. I thought he had been incredibly understanding and uncomplaining, though, after I took up with Caryn, throwing so many of his and my long-established habits and plans in the dustbin. Separation is a bitch. He and Caryn had even become friends.

In fact, Domenic, who was about to turn nineteen and was not in school, was having trouble with his draft board, and he had settled on a scheme to avoid conscription that involved a quick trip to Canada, and Caryn, who was also not in school, had volunteered to hitchhike up there from California with him. I, in my innocence, thought that was damn nice of her.

Finally, around midday, other people started showing up at Honolua. Cars appeared on the cliff top, guys scrambled down the trail. The crowd never got bad, though, and the waves, if anything, got even better. I was riding an odd-looking, ultra-light, homemade board. It was odd-looking mainly because the deck was full of big dents. In a misguided attempt to reduce weight, some backyard glasser in Santa Cruz had glassed the deck so lightly that my chest and knees when I paddled, and even my feet when I stood up, left permanent impressions. But the bottom, the planing surface, was smooth and hard, the rocker subtle and sure, and the shape was clean, with undented, slightly downturned rails and a gently rounded tail, and the board turned quickly and flew down the line and the fin held in the barrel, and those were the things that mattered. The board was actually too light for Honolua, especially when it got bigger and windier in the afternoon. But fighting it down the late drops, and banking it through the slight chop, and then setting it into the face under the high, screamingly fast, backlit hook, I was unusually conscious of the technical challenges involved in each maneuver. More generally, I knew I had never ridden waves so powerful on equipment so flimsy before, and while I might have preferred a different board out there, I could not imagine a more soul-stirring wave. I wanted more of it. All I could get. Plato could wait.

• • •

THREE MONTHS LATER, I had dropped out of college and moved to Lahaina. UC Santa Cruz was an exciting place, but it was easy to leave. It was a new campus, a hotbed of academic experimentation. There were no grades, no organized sports. Professors weren’t authority figures but coconspirators. Maximum self-direction was encouraged. All of this suited me, but the place had no institutional gravity.

Caryn, although dubious, came along. She had zero interest in surfing, but she was adventurous, and I could not live, could not breathe, I believed, without her. Fortunately for me, she had no other plans. The flight from Honolulu to Maui cost, as I recall, nineteen dollars, and the hard fact was that on arrival we could not, between us, afford a single plane seat back to Honolulu. We slept on the beach that night, wrapped in beach towels, with crabs scuttling across us. The crabs were harmless yet weirdly terrifying. Then it rained, and we shivered till daybreak. My parents, when we’d passed through Honolulu, had made their unhappiness with my decision to leave school painfully clear. Now Caryn made her unhappiness with me clear as well, in the Lahaina dawn. In the year and a half we had been together, I had dragged her around on the basis of cracked ideas and whims of mine quite a lot. Now she was supposed to become a homeless, hungry surf chick?

I knew a guy, I told her. And I did, very slightly. I had met him on the street three months before, while on a supply run to town with Domenic, and he had pointed out where he lived. Now, by trial and error, through the muddy back blocks of Lahaina, I found my way to his place. I went inside. Caryn waited in the alley. She was surprised, I think, when I emerged with a set of car keys. I know I was. But the car’s owner—a surfer, scholar, and stunningly kind older gentleman of twenty-two named Bryan Di Salvatore—had welcomed me like an old friend and, hearing about our tenuous situation, had immediately loaned us his 1951 Ford. All the waves this time of year were in town, he said, and he worked in town, so he didn’t need a car. We could live in it while we looked for jobs. The car’s name, he said, was Rhino Chaser. It was the turquoise beast parked under the banana tree.

If Caryn had been in a better mood, she would have said, with a grin and a smirk, “God provides.” But she was still feeling suckered and skeptical. I took her on a car tour of the old whaling town turned tourist town, including the food-stamp office, where we collected an emergency monthly ration for two—thirty-one dollars, as I recall—and a series of hotels and restaurants, all of which were taking applications. Caryn quickly scored a job as a waitress. I had my eye on a bookstore on Front Street. We couldn’t afford the gas to drive out to Honolua Bay, but I promised her she would love it.

“Why, because it’s pretty?”

Among other reasons, I said.

In the meantime, we had to park at night in dark farm roads near town, with Caryn trying to sleep in the front seat, me in the back, and my board under the car. (I slept with one door open and a hand on the upturned fin, to discourage thieves.) We used the facilities at public parks, Caryn washing her waitress uniform in the sinks. I surfed a couple of the town breaks; she read, and seemed to relax. I was still in the doghouse, I could tell, though, from the sex we were not having. Fortunately, I landed the job at the bookstore.

It was a strange place, called the Either/Or, after Kierkegaard, although more immediately after a larger store in Los Angeles, of which it was an offshoot. The owners, a nervous couple, were on the run from the law, and so was their one employee, a red-bearded draft dodger who went by a variety of names. They needed help, but all regarded me warily. Did I look like a federal agent? I was eighteen, rail-thin, with scraggly shoulder-length hair, a sardonic girlfriend, worn-out flip-flops, sun-faded trunks, a disintegrating T-shirt. They decided to take a chance. They had a comprehensive book-knowledge test, imported from the L.A. store. All prospective workers had to pass it. (The retail book business has changed since then.) The test was written, and was not take-home. Caryn spent an evening drilling me on titles and authors. It occurred to me that she had a better chance of passing the test than I did. (She later worked in a French-language bookstore near UCLA.) She was, in fact, the most widely read teenager I knew. As I surfed in the afternoon glare off Lahaina Harbor, she curled up on the seawall with Proust, in French. Still, I took the Either/Or test, and I got the job.

On my first day behind the counter, Bryan Di Salvatore rushed in. He was leaving town, he said. Something about a letter from an old friend on a ranch in the Idaho panhandle had made him realize his time on Maui was up. He scribbled an address on an Aloha Airlines ticket folder. I should pay him for the car when I had the money, send it care of his parents in L.A. Whatever I thought it was worth. He had paid $125 for it a year before. With that, he was gone.

With paychecks, Caryn and I could afford gas, though not yet rent. We started camping on the coast out west and north of Lahaina. It was a serpentine series of bays and headlands. There were rows of old cane shacks—worker housing, red paint peeling—at the edges of cane fields that ran up a long terrace to sheer, rain-dark mountains. Puu Kukui, the highest peak of the West Maui range, was the second-wettest spot in the world, people said. We found secluded coves where we could build campfires, and beaches with water as clear as gin. I showed Caryn how to find ripe mangoes, guavas, papayas, wild avocados. We scrounged masks and snorkels and explored the reefs. I still remembered the names of some Hawaiian fish. Caryn especially liked the humuhumunukunukuapua‘a—not the fish itself, which isn’t much (a blunt-nosed triggerfish), but the name. She would surface from a dive, pull out her snorkel, and ask, “Humuhumu?” The word developed many meanings. I might look at the angle of the sun and answer, “Hana hana.” That means “work” in Hawaiian. We had to get to our jobs. Caryn did like Honolua Bay, as it turned out, which was a relief. The bay was too far from town for every-night camping, but the diving was good, with brilliant fish. And the place was undeniably pretty. There would be no waves there till fall, but neither of us had anywhere else to be.

Caryn should by rights have been a stability freak—an ant, not a grasshopper (or gracehoper, vide Joyce). Her mother and her mother’s parents were German Jews and Holocaust survivors. Caryn’s own life had imploded when she was thirteen, after her parents got into LSD and split up. She and I had been school friends at the time, and what I pictured was a suburban wife-swapping party presided over by Timothy Leary. Caryn disappeared into something called the Topanga Free School, the first of the “alternative” schools in our part of the world. When I next ran into her, she was sixteen. She seemed sad and wise beyond her years. All the giddy experimentation with sex, recreational drugs, and revolutionary politics that was still approaching its zenith in countercultural America was ancient, unhappy history to her. Actually, her mother was still in the midst of it—her main boyfriend at the time was a Black Panther on the run from the law—but Caryn, at sixteen, was over it. She was living in West Los Angeles with her mother and little sister, in modest circumstances, going to a public high school. She collected ceramic pigs and loved Laura Nyro, the rapturous singer-songwriter. She was deeply interested in literature and art, but couldn’t be bothered with bullshit like school exams. Unlike me, she wasn’t hedging her bets, wasn’t keeping up her grades to keep her college options open. She was the smartest person I knew—worldly, funny, unspeakably beautiful. She didn’t seem to have any plans. So I picked her up and took her with me, very much on my headstrong terms.

I overheard, early on, a remark by one of her old Free School friends. They still considered themselves the hippest, most wised-up kids in L.A., and the question was what had become of their foxy, foulmouthed comrade Caryn Davidson. She had run off, it was reported, “with some surfer.” To them, this was a fate so unlikely and inane, there was nothing else to say.

Caryn did have one motive that was her own for agreeing to come to Maui. Her father was reportedly there. Sam had been an aerospace engineer before LSD came into his life. He had left his job and family and, with no explanation beyond his own spiritual search, stopped calling or writing. But the word on the coconut wireless was that he was dividing his time between a Zen Buddhist monastery on the north coast of Maui and a state mental hospital nearby. I was not above mentioning the possibility that Caryn might find him if we moved to the island.

• • •

WE RENTED A ROOM in town from a crazy old man named Harry Kobatake. One hundred dollars a month for a roach-infested sweatbox with a toilet down the hall. We cooked our meals on a hot plate on the floor. The rent was high, but Lahaina had a housing shortage. Also, Kobatake’s rooming house was directly across Front Street from the harbor, where two of the best local waves broke. Bryan had been right—the good summer waves were all in or near town. One spot, called Breakwall, needed real swell to be ridable. Over four feet, it could produce sweet lefts and rights on a jagged reef straight off a rocky breakwater that ran parallel to shore. The other spot, known as Harbor Mouth, was a crisp, ultra-consistent peak on the west side of the harbor entrance channel. It was good even at one foot, crowded, and picked up every hint of south swell. The crowd was largely haole, not local. That became my bread-and-butter spot.

I would get up in the dark, tiptoe down the stairs barefoot with my board, and jog across a little courthouse park to the wharf, hoping to be the first one out. I often was. A lot of mainland surfers had fetched up in Lahaina that year, but they were a hard-partying lot, which cut down on the number of guys ready to hit it at dawn. Caryn and I were by contrast a sober pair, and knew few people. I closed the Either/Or at nine. From her job she brought me tinfoil packages of aku and mahimahi that customers hadn’t touched. And those were our evenings, eating and reading and killing cockroaches that got too bold. We named the geckos that patrolled the ceiling. I was so indifferent to bar life that when a tourist asked me the legal drinking age in Hawaii, I had to admit I didn’t know.

Harbor Mouth had a short, hollow right that got longer and more complicated as the surf got bigger and the takeoff moved farther out the reef. Still, it never got very complicated. It was a wave that one could get wired—could come to understand deeply—in a summer dedicated to the task. I loved it at five feet and up, when, with clean conditions, the outside wall presented a perfectly even face and people often got fooled, moving too deep or too far out on the shoulder, unsure where to take off. There was a deep spot from which a six-foot wave, caught early and ridden correctly, could nearly always be made, and I got to know where that was, even though it gave no visual clues. Harbor Mouth’s signal feature, though, its claim to whatever fame it had, was the end-section on the right (there were also longer, less shapely lefts, running away from the channel). It was a very short, thick, shallow, highly reliable chunk of wave that almost always stayed open. If you timed it right, that section was as close to a guaranteed barrel as any wave I’ve seen. Even at two feet, you could squeeze through it and come out dry. For the first time in my surf career, I became accustomed to the view from inside, looking out from behind a silver curtain toward the morning sun. I had sessions where I got tubed on half my rides. I would trot back to Kobatake’s, where Caryn was still asleep on our pallet on the floor, my brain aflame with eight or ten brief, sharp glimpses of eternity.

I took to surfing Harbor Mouth in the black of night, after work. The tide had to be high, and the swell good-sized, and a moon could help. Even so, it was a fairly insane thing to do. It was basically surfing blind. And I usually wasn’t the only one trying to do it. But I thought I knew the break so well, after a while, that I could feel—from the shadows, from the pull of the current—where to be, which way to go, what to do. I was often wrong, and spent a great deal of time hunting for my lost board in the shallows. That was the reason it had to be high tide. The lagoon inside Harbor Mouth was broad and shallow, with sharp coral covered with cruel sea urchins. In daylight I knew the little rivulets in the reef that one could float down, eyes open underwater, chest full of air for maximum flotation, skimming over the purple urchin spines, even at lower tides, in pursuit of a lost board. At night, however, one could see nothing underwater. And a search for the faint glistening ellipse of one’s board, bobbing in the lagoon among all the bathtub chop dancing in the glare from the seafront streetlights, could take a whole different type of eternity from the one glimpsed in the tube. Giving up was not an option, though. I had only one board, and I always found it.

• • •

THE BOOKSTORE WAS three small rooms on a rickety old pier at the west end of the seawall. There was a bar next door. Ocean sloshed under the floorboards. The couple who owned the store trained me and, having picked up danger signals from local authorities, fled Hawaii for the Caribbean, leaving me to run the place along with the draft dodger, one of whose names was Dan. It was a terrific store for its size. Its fiction, poetry, history, philosophy, politics, religion, drama, and science sections were lively and thorough, with room for only single copies of most titles. Every book ever put out by New Directions or Grove—my favorite publishers in those days—seemed to be there. And we could get almost any title we didn’t have in a matter of days, on special order. All this stock and capacity were courtesy of the big store in L.A.

And yet nobody wanted to buy all the wonderful books we had. What we mainly sold were coffee-table volumes to tourists: high-markup fifty-dollar monsters, stuffed with bright photos of coral reefs and local beauty spots. Then, every two weeks, tall stacks of Rolling Stone and, every month, even taller stacks of Surfer. Those were our profit centers. Our occult, astrology, self-help (though we may have called it self-realization), and Eastern mysticism sections also sold smartly. Some of the authors we had to order in bulk were old-school frauds like Edgar Cayce; others were nouveau gurus like Alan Watts. Then there were the counterculture bestsellers, which we ordered by the case and sold out quickly. One was Be Here Now, by Baba Ram Dass (formerly Dr. Richard Alpert), which came from Crown and, I recall, sold for the occult sum of $3.33. It counseled a heightened consciousness, with many diagrams. Another major seller was Living on the Earth, by Alicia Bay Laurel, which was large-format, hand-illustrated, and offered practical guidance to people trying to live gently and penniless in the countryside, without electricity or flush toilets.

There were many such people on Maui at the time, virtually all of them newly arrived from the mainland. They were living up narrow mountain valleys, off dirt roads or jungle footpaths. Or they were living somewhere on the broad slopes of Haleakala, the enormous old volcano that defined the eastern half of the island, or out on remote beaches along the bone-dry southeast coast. Some were making a serious go of commune life and organic tropical farming. Some surfed. There were also plenty of new arrivals scraping by in towns and villages, like us in Lahaina. Or like Sam at his monastery, which was reportedly on the north slope of Haleakala.

What about local people? Well, none of them came into the Either/Or, that was certain—when I told Harry Kobatake I had a job there, he said he’d never heard of the place, and he’d lived in Lahaina, which was a very small town, for sixty years. Our customers were all tourists, hippies, surfers, and hippie-surfers. Without particularly thinking about it, I began to dislike all four groups. I found myself proselytizing from behind my little bookstore counter, trying to get people interested in reading literature, history, interested in anything besides their souvenirs, their chakras, their pit latrines. I got nowhere, and my college-kid arrogance began to harden into disgruntlement. I felt suddenly old, like some kind of premature anti-hippie. Caryn, who had been there ideologically for years, thought it was funny.

The beautiful people were also starting to make appearances locally, mainly by yacht. Here came Peter Fonda’s ketch, there went Neil Young’s schooner, with “Cowgirl in the Sand” blaring from the deck speakers as it sailed off toward Lanai at sundown. Caryn felt intimidated by the leggy groupies who stalked off these luxe vessels until she had a reassuring experience in a public restroom at the harbor across from Kobatake’s. Someone was giving the loudest, most fetorous performance ever in one of the women’s stalls. Caryn tried to hurry her own ablutions to avoid the embarrassment of encountering the woman, but she wasn’t quick enough, and, of course, the blushing starlet who emerged was straight off some rock god’s boat.

The rock star who cheered me up, socially speaking, was Jimi Hendrix, as he appeared in a curious film called Rainbow Bridge, about a concert he had given the year before on Maui. The film was rough, and the sound bad, as Hendrix and his band played in a scrubby field in a howling trade wind. There was a sketchy, cinema-verité romance between Hendrix and a willowy black woman from New York. She was holding the Maui hippie commune scene at arm’s length, and Hendrix was holding it farther away than that. His slurred, throwaway lines made me laugh. A passive-aggressive commune leader named Baron got so annoying that Hendrix was obliged to pick him off a balcony with a rifle. The movie ended with a no-budget sequence about “space brothers” from Venus landing in the crater at Haleakala. I took the ending as pure spoof. But the more talk I heard, in the bookstore and elsewhere, about “Venusians,” the more I realized that mine was a minority interpretation.

We weren’t entirely at odds with our little makeshift community, Caryn and I. There was another movie, a hard-core surf film, that I dragged her to. Hard-core surf films are essentially meaningless to anyone who doesn’t surf. An old ramshackle movie house in Lahaina, the Queen Theater, played them occasionally, always to sold-out, stoned-out crowds. I remember a few sequences (though not the title) from this particular film. One sequence was of giant Banzai Pipeline, and the filmmakers, lacking a soundtrack, played the Chambers Brothers’ slow-building anthem “The Time Has Come Today” full blast. Everyone in the movie house seemed to be on their feet screaming with disbelief at the screen. It was electrifying, for people like us, to watch guys pulling into such apocalyptic waves. But I remember being surprised to see Caryn also on her feet, her eyes popping.

Then there was a sequence of Nat Young and David Nuuhiwa surfing one of our local spots, Breakwall, to a much gentler score. Nuuhiwa had been, a few years before, the world’s best nose-rider, and Young had been the first great shortboarder, and it was moving to the point of tears to see them surfing together, both on shortboards now, both still absolute maestros—the last dauphin of the old order and the strapping, revolutionary Aussie, playing a kind of sun-drenched duet in waves we all knew well. I doubted that Caryn got all the implications of the Nuuhiwa-Young set, but she definitely got the bit that followed. The filmmakers had, on poor advice, tried to include some comic land segments—always a bad idea in a hard-core surf film. One involved a villain running around wearing a face-distorting mask made from a nylon stocking. The crowd groaned and somebody bellowed, “Fuck you, Hop Wo!” Hop Wo was a Lahaina shopkeeper with a reputation for surliness and tightfistedness. The bad guy in the nylon did bear a resemblance. Caryn laughed along with the surf mob, and “Fuck you, Hop Wo” became a complex, sweet refrain between us.

• • •

I SENT BRYAN DI SALVATORE $125 when I had it. I didn’t hear back from him directly, but an elegant woman named Max often came by the bookstore and sometimes had news of him. He was in Idaho, then England, then Morocco. I couldn’t figure Max. She was boyish, in a fashion model sort of way, with a low voice and an amused, direct gaze. She seemed out of Lahaina’s league—like she should be in Monte Carlo or somewhere. She and Bryan had clearly been an item, but she seemed quite cheerful about his absence. I wondered what she thought when she saw his old car. Caryn had painted a huge flower on the trunk, at my instigation. It was a well-painted flower, but still. It was no longer a car you could call Rhino Chaser. I say I was becoming anti-hippie, but I retained certain tendencies.

I heard very little from my parents. Their objections to my leaving school still rang in my head. My father had insisted that 90 percent of all college dropouts never returned to get a degree—“Statistics show!” They were probably also worried, understandably, about my draft status. What they didn’t know was that I had never registered. My sense of civic obligation, never strong, was nonexistent when it came to the military. Maybe, if the feds came looking for me, I’d end up in the Caribbean with the Either/Or’s owners. In the meantime, I never thought about it. My folks had also insisted that Caryn and I sleep in separate rooms while we stayed with them in Honolulu. That had been the crowning insult.

Our neighbors at Kobatake’s were a rowdy, dope-smoking crew, prone to skateboarding in the hall, loud music, and louder sex. They seemed to be constantly playing Sly and the Family Stone; I would never enjoy the band’s albums again. I embarrassed Caryn by frequently flying out of our room, book in hand, to glare at noisy debauchees. Actually, I didn’t know then that she was embarrassed. She only told me years later. She even showed me her journal, and there I am, “our fervent scholar” sticking my “crazed head out in the hall” and causing her “endless chagrin.” I didn’t mind being disliked, but she did—yet another inconvenient point I didn’t trouble to notice.

Everybody at Kobatake’s got food stamps. Indeed, everybody who had ever lived there seemed to have gotten them. “At the usual time of the month, the pink came,” was how Caryn’s ever-mordant journal put it. She meant the dozens of pink government checks that arrived for residents both current and departed. This mass reliance on food stamps carried, among our loose group of peers on Maui, no particular assumptions, I thought, about the welfare state. Food stamps were viewed as just another hustle—strangely legal and easy but decidedly minor. I later lived among young able-bodied dole bludgers in England and Australia (some of the latter were surfers) who saw their government checks as essential sustenance and a type of right.

One day when we were both off work, Caryn and I went out in dribbly surf at a spot called Olowalu. It was a shapeless little reef southeast of Lahaina, off a flat part of the coast where the road ran next to the shore. Caryn had no interest in learning to surf, which I thought sensible. People who tried to start at an advanced age, meaning over fourteen, had, in my experience, almost no chance of becoming proficient, and usually suffered pain and sorrow before they quit. It was possible to have fun, though, under supervision, in the right conditions, and today I had talked her into trying the slow, tiny waves on my board. I swam alongside, propelling her out, getting her into position, pushing her into waves. And she was in fact enjoying herself, getting long rides on her belly, yipping and hooting. I was just trying not to get cut on the rocks—the water was shallow and did not look or smell particularly clean. There was no one else around, only cars whizzing by on the road to Kihei. Then, as Caryn finished a ride, slipping down the wave’s back as it passed into the inshore lagoon, I saw four or five dorsal fins beyond her: sharks cruising parallel to the shore.

They looked like blacktips—not the most aggressive local species but still an extremely unwelcome sight. They didn’t look big, though it was actually impossible to tell from where I was. They were right next to shore; I was thirty yards out. Caryn, who was just a few yards from the beach, obviously didn’t see them. She was splashing, trying to turn the board back out toward sea. I put my head down and swam in her direction as hard, without thrashing, as I could. Caryn was saying something, but the blood roaring in my ears drowned her out. When I reached her, I saw that the sharks had turned around. They were still cruising close to shore, now coming back toward us. I stood up, in waist-deep water, trying to see their bodies, but the water was muddy. I kept my face averted as they passed us. I didn’t want Caryn to see my expression, whatever it might be. She was surprised, I imagine, when I turned her toward shore and started a fast march for the beach, ignoring the rocks I had been so careful about not touching on the way out. Still, I don’t recall her saying a word. I angled the board so that I blocked her view of the sharks, and so that we would reach the beach well behind them, assuming they didn’t turn again too soon. They didn’t turn, at least not while we were crossing the lagoon or scrambling onto the sand. I didn’t look back after that.

Caryn and I were in weird territory. I was deeply involved with my old mistress, surfing. I was waiting with passionate expectation for Honolua Bay to start breaking in the fall—tuning up, tuning up, surfing every day. Caryn, who had never seen me in this state, didn’t seem jealous. In fact, she began making discreet inquiries about the technical aspects of my ideal Honolua board. This was a line of questioning so unlikely that she was forced to confess her plan: she wanted to get me a new board for my birthday. With our food-stamp-qualified incomes, this was no small gift. So I was waiting for Honolua, and she accepted that. But what exactly, again, was she doing on Maui? She had quit her waitress job and was now scooping ice cream at an awful new resort outside Lahaina called Kaanapali. We had made some effort to find her father, driving over to Kahului and Paia, asking around at a monastery and an outpatient clinic, but we hadn’t followed up on the slim leads we got. I had started to wonder if she really wanted to ambush him. It could be painful, to say the least. Lahaina had its charms. They were subtler than those of the west Maui coast and countryside—old Chinese temples, some amusing eccentrics, coral-block prison ruins baking in the sun—and yet Caryn was alive to them. She even made a few friends among the other surf migrants—what she called “the bands of blond suncreatures.” But the weirdness between us began with our failure—my failure, really—to make any serious distinction between her desires and mine.

We had been merged, fused, our hearts’ boundaries dissolved, at least in my mind, since we got together in high school. Physically, we were an unlikely pair. I was more than a foot taller. Caryn’s mother, Inge, liked to call us Mutt and Jeff. But we felt like one body. I experienced our separations deep in my chest. When we were still in high school, and Inge’s nights had seemed to be one long middle-aged orgy, Caryn and I were the resident young Puritans—quaintly monogamous, devoted entirely to one another. Their apartment was an unusual household even then—a place where the kids were free to have sex yet pitied for their unadventurousness. It took me a while to get used to that freedom, after an adolescent love career of dodging (or failing to dodge) watchful, sometimes irate dads. My parents never did get used to it, throwing fits, after I took up with Caryn, when I failed, as I often did, to come home at night. Their ire surprised me. For years I had felt like what Caryn called, with mock solemnity, “a free agent of God.” Now, at seventeen, I suddenly had a curfew? My own sullen diagnosis: parental sexual panic.

Then Caryn and I got in a car accident. We were on a camping trip up the coast when a speeding drunk rear-ended my van. The van was totaled. We were both unhurt. But we got a small insurance settlement, and we took that money, bought dirt-cheap charter-flight tickets, and split for Europe, skipping our high school graduations. This abrupt exit settled my parents’ hash, I thought. Its potential cruelty never crossed my mind. Had my parents been looking forward to the graduation of their firstborn? If so, they didn’t mention it. Inge, for her part, seemed to wake up and freak out just as we left, making me promise to take care of her little girl.

I didn’t really do that, though. We had started to quarrel, Caryn and I, and we didn’t fight well. On the road, moreover, I turned into a tyrant, setting a merciless pace as we bummed around Western Europe, living on crackers and fresh air, sleeping under the stars. There was always someplace new, someplace better, we had to be. I dragged her on grueling pilgrimages to rock festivals (Bath) and surf towns (Biarritz) and the old haunts (and graves) of my favorite writers. Caryn, less callow, did not see the reason for all the hurry. She pressed dried flowers in her journal, went to museums, and, already fluent in French and German, undertook to learn each language we encountered. She finally dug in her heels on the western Greek island of Corfu after I announced that I had a burning desire to see more “Turkish influence.” I could go hunt for Ottoman minarets on my own, she said. And so I up and left her on the remote, mountain-backed beach where we were camping au naturel. Neither of us, I suppose, believed I would really do it, but I had become adept at, if nothing else, moving quickly through strange territory at low cost, and within a week I was in Turkey itself, newly intent on traveling overland to India. Motion, new companions, new lands were my drugs in those days—I found they did wonders for the adolescent nerves. Turkish influence fascinated me for about half an hour. Then only Tamil influence would do.

Istanbul, 1970

This folly came to a grubby halt on an empty beach on the south coast of the Black Sea. Mediocre surf, brown and misty and blown out, was rolling in from the general direction of Odessa. I was stumbling along through brushy dunes. What, exactly, was I doing? I had left my true love alone in the boondocks of Greece, abandoned her on the roadside. She was seventeen, for Christ’s sake. We both were. My lust for new scenes, new adventures, vanished in a bitter puff as I sat there in the Turkish scrub, not bothering to make camp. Dogs barked and darkness fell and I suddenly saw myself not as the dauntless leading lad of my own shining road movie but as a hapless fuckup: deadbeat boyfriend, overgrown runaway, scared kid in need of a shower.

The next morning I started back toward Europe. Europe turned out to be harder to reenter than it had been to leave. There was a cholera scare, and the borders with Greece and Bulgaria were reportedly closed. I bounced around Istanbul, walking along the Bosporus, sleeping on hotel roofs (cheaper than a room). I tried to go to Romania, but Ceausescu’s sentinels reckoned I was a decadent parasite and refused me a visa. Then the police raided a flophouse where I was staying. They arrested three Brits, who were convicted the next day of hashish possession and sentenced to several years each. I moved to another roof. I wrote brave, boastful postcards: Hey, no photograph could do justice to the beauty of the Blue Mosque.

But I was frantic about Caryn. Although she had said that she would find her way to Germany, where we had friends, I kept imagining the worst. I bought her a cheap purse in the Grand Bazaar. I befriended other stranded foreigners. Finally, I broke down and phoned home. It took all day, hanging around the vast old post office, to get through. Then the connection was awful. My mother’s voice sounded terribly frail, as though she had aged fifty years. I kept asking what was wrong. I told her I was in Istanbul, but I still hadn’t asked for news of Caryn—nor mentioned that I hadn’t seen her in weeks—when the line went dead. Now the post office was closing. I wrote many cards and letters, but that was the only call home I made that summer.

In the end, I teamed up with other desperate Westerners, bribed some Bulgarian border guards, made my way through the Balkans and over the Alps, and, with the help of an American Express office message board in Munich, found Caryn in a campground south of the city. She seemed fine. A little wary. I was scared to ask too much about what she’d been up to. Yes, I said, I’d got my fill of Turkish influence. She accepted the purse. We resumed our rambles: Switzerland, the Black Forest, a supremely strange visit to Caryn’s mother’s hometown on the Rhine. There, old people kept mistaking her for her mother, and then denouncing neighbors in whispers to us as ex-SS. In Paris we spent our first night sleeping on the ground in the Bois de Boulogne. In Amsterdam we heard that Jimi Hendrix would be playing in Rotterdam. We planned to go. But then the show was canceled and, five days later, Hendrix was dead. (The Maui film about him had been shot just a few weeks before.) Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison, two more heroes of mine, were also dead by then.

We flew back to California and camped together, Caryn illegally, in my tiny dorm room in Santa Cruz. It was a funky arrangement, with me stealing food for her from the cafeteria, but we weren’t the only hippie outlaw freshman couple doing it. For me, at least for a while, it was ideal. I was awash in books and great teachers, pacing barefoot through the redwoods, arguing Aristotle, with my beloved never far away. Caryn was auditing classes, hitchhiking here and there (L.A., fornicating Canada), and starting to think about her own college career. Then I got the luminous, numinous idea of Maui, and dragged her there.

We were bound together tightly, inevitably, during those first months. When Kobatake tried to raise our rent—or to fine us over some imaginary theft of his chickens, or to evict us when he thought he had some suckers on the line willing to pay more—we fought back together. When people we knew talked, straight-faced, about Venusians, we had each other. We were fellow skeptics—rationalists, readers of books in a world of addled, inane mystics. Still, we were quarreling again. It was usually hard to say about what, but arguments would escalate, spin out of control, and one of us would storm off into the night. Makeup sex could be sublime, but that was starting to be all the sex there was.

The weirdness deepened after Caryn got pregnant. We never discussed having the child. We were still children ourselves. I was also immortal, I secretly believed. There would be time for all that—many lives from now. Caryn got an abortion. In those days, that involved a night or two in the hospital in Wailuku. After the procedure she looked awful, curled in a ball in a ward bed, her face drawn, her eyes injured. We drove back to Lahaina in silence. That, as I understand it now—I was nowhere near understanding it then—was pretty much the end of us.

• • •

ONE OF THE FLOWER-CHILD tendencies I retained, even in this period of antiutopianist reaction, was a closet communardism. I wanted, in an ill-defined way, to gather a group of friends in some soulful place and all live happily ever after. Maui, which seemed to be getting sillier and more touristy by the day, didn’t entirely fit the bill, but I enticed a series of friends, including Domenic and Becket, to come stay with us in Lahaina nonetheless. They came, and squeezed in with us for weeks at a time on the floor at Kobatake’s. It seemed clear, later, that I was unwittingly hoping to reconstitute a kind of family circle. I had left home, effectively, at a very young age, and for many years felt a poorly understood compulsion to build myself a new shelter from the world—even as I declined to start a biological family with Caryn and seemed to roam the globe under an opposite compulsion. Still, in Lahaina I made no real effort to find digs more suitable for a bigger group, probably because I knew a communal house wouldn’t really work. Caryn and I were too shaky. Also, she was the only girl.

Certainly Domenic knew it wouldn’t work. It became obvious, when he stayed with us, that something had happened on his and Caryn’s draft-evasion lark to Canada in the spring. Obvious to me, that is. They already knew all about it. I never asked for details. I was horrified, and furious, but I tried to put the best face on things. Maybe we could comprise a ménage à trois. Hadn’t we all seen Jules and Jim? Sung along with the Grateful Dead, “We can share the women, we can share the wine”? Domenic, with his Senecan grasp of the possible, bowed out and went back to Oahu, where he now had a job working for my father, who was producing the TV series Hawaii Five-0.

Domenic was a gardener on the show’s set on Diamond Head Road—hot, nasty work—but he and my father seemed to have an understanding. I was vehemently uninterested in the film business; Domenic did not share my antipathy. My father, who admired Domenic’s readiness to work, wanted to help him get a leg up in Hollywood’s tightly closed craft guilds. Domenic took the help gladly. He eventually moved back to Los Angeles, became a film editor, then a cameraman, then a director. Many years later, in a Godfather moment at his wedding, his father, Big Dom, thanked my father with tears in his eyes. He was happy, I think, that his son had not gone into his business. Did young Domenic see the career opportunity when he moved back to Oahu? I doubt it. I know I watched him go with mixed feelings, which included astonishment that he could bear to leave Maui before Honolua Bay had started breaking.

I should say something here about Los Angeles, moving back to. It was an article of faith among our circle of young ex-residents that L.A. equaled living death. If Ireland was the sow that ate its farrow, L.A. was the John Wayne Gacy of cities, smothering its children with a toxic beach towel of poisoned air, mindless growth, and bad values. Whatever we were looking for—beauty, wisdom, uncrowded surf—it wasn’t there. Or so we believed. (When I later learned that Thomas Pynchon, one of my undergraduate literary heroes, had apparently lived in Manhattan Beach, in the dreaded South Bay, in the late ’60s and had found its grubby, bleached-out vitality inspiring, I suddenly saw it differently. I felt brought up short by my own shortsightedness, my unoriginality. Then again, I loathed the novel that his South Bay research ultimately produced.) The persistent nostalgia that infected most surfers, even young ones—the notion that it was always better yesterday, and better still the day before—was related to this dystopian view of Southern California, the suburban megalopolis that was, after all, the capital of modern surfing and head office of the nascent surf industry. But we took this nostalgia with us wherever we went. In Lahaina my imagination was captured by the news that the town had once contained a great river, big enough for whaling ships to sail up and take on freshwater. It made sense. If Puu Kukui, straight up the mountains, was the second-rainiest spot in the world, where was all the runoff? Diverted for irrigation by the corporations that grew the sugarcane all over west Maui, of course. Modern Lahaina was, as a result, parched, dusty, and unnaturally hot.

By the time Becket joined us, Caryn and I, exhausted from fighting, were practically on the rocks. She got a room of her own in a collapsing warren of worker housing next to an old sugar mill on the north side of town. Lahaina had a gender imbalance, at least among its young arrivistes—there were way more men than women—and I was certain I saw a lot of the dudes around town taking note that the tasty little dark-haired haole girl from the ice-cream parlor was now living alone. Even Dan, the simpering draft dodger at the Either/Or, started putting the moves on her. I had been writing an epic poem, full of stormy tropical imagery, called “Living in a Car.” Now I turned my hand to a short story about a Filipino canecutter in Hawaii who spends his best years in a single-sex barracks, then falls in love with a blow-up sex doll. My situation wasn’t quite that dire, but I was not happy.

• • •

CARYN, WITH HER SOFT HEART, was still intent on getting me a new board. So I settled on a shaper, Leslie Potts. He was the reigning monarch of Honolua Bay, a leathery, soft-spoken surf wizard and blues-rock guitarist. I tried to tell him what I wanted—something light, quick, fast—but found myself tongue-tied. He wasn’t interested anyway. He had seen me surf Harbor Mouth. More than that, he knew Honolua in all its moods, demands, and supreme possibilities. He was going to shape me a thick, unfashionably wide 6'10" that would handle the drops, carve short-radius turns, and go like the wind. It was not the shape or length I would have chosen, but I trusted Potts. He was the consensus best surfer on Maui, and people said that when he could be bothered, he shaped as well as he surfed. Surprisingly, he delivered my board in good time. And it did look like it might be magic. Something about the arc of the rocker made the shaped blank look alive.

I had more control over the glassing. Potts’s glasser was a quiet, bespectacled guy named Mike. I wanted a single layer of six-ounce glass on the bottom, six and four on the deck, with a rail overlap. This was considered foolishly light for a Honolua board, if only because of the terrible punishment that the cliff administered to lost boards, but I wanted to compensate for the bulk in the foam. Mike followed my directions. I ordered honey-colored solid pigment for the deck and rails, with a clear bottom. There would be no sticker: Potts was strictly underground.

Becket and I checked the northwest shore daily. It was now early fall; the North Pacific was starting to stir. Some people said there was never a Honolua swell before the humpback whales arrived in November. We prayed they were wrong. Becket had shown up on Maui looking wan—easily the palest I had ever seen him. He had had a difficult couple of years. A caper in Mexico had gone wrong and left him with amoebic dysentery, ending both his high school and his basketball careers. More recently, kidney surgery had kept him in bed for months. He was now good to go, he said, but he was obviously weak. We surfed around Lahaina, and he slowly seemed to regain strength. He was riding a little pintail only a couple of inches longer than he was tall. He had developed a forward-leaning, dropped-hands style that was new but seemed to work. It wasn’t clear if he was in Hawaii on vacation or intended to stay. He had a few shekels saved, as he put it, and was not yet looking for a job. It was clear, though, that the islands suited him, temperamentally, down to the ground. He would shamble along the Lahaina waterfront, looking in the buckets of fishermen, just as he had as a kid on Newport Pier. The town had yachts and groupies, two of his favorite things, in healthy numbers. More generally, the pig-roasting, ukulele-picking, sea-centered rhythms of rural Hawaii appealed naturally to a child of San Onofre, now pursuing his own PhD in having fun. Like the rest of us, Becket was in spiritual flight from Southern California—Orange County was growing even faster and more grossly than L.A. Domenic had taken to saying that Becket would end up a fireman, like his dad. In fact, he had inherited his father’s woodworking talent, and that would be his trade.

Honolua began to break, in a marginal sort of way. Becket and I surfed it stupidly close to the cliff, keeping death grips on our boards. I started getting used to the Potts, which snapped smoothly out of the hardest turns I could conjure. Indeed, it turned so sharply off the bottom that in small waves I often wasn’t quick enough to change rails—shift my weight off the inside rail, the toe rail, to my heels—and unintentionally flew out over the top. It wasn’t a big-wave board—the shape was too rounded, too ovoid—but it was plainly built for fast, roomy, powerful waves.

One day I saw a heart-stirring thing in a surf mag. It was a photo of Glenn Kaulukukui at Pipeline. I had heard nothing about him for years, and now here he was, instantly recognizable in silhouette on a glittering, extremely serious wave. You couldn’t see his expression, but I was sure it contained none of his old irony, no playful ambivalence. This wave was the big time. Very few surfers would ever ride anything comparable. No one could take it lightly. The picture meant that Glenn had grown up, had survived, and was now surfing at a very high level. His stance in the closing jaws of the Pipeline beast was stylish and proud—almost Aikau. Years later, I saw another shot of him in another mag. Again, he was in silhouette, this time surfing Jeffreys Bay, a pointbreak in South Africa. It was a great picture, classically composed, expressively lit, with strong offshores raking an endless wall, and it had a powerful subtext because Glenn, in profile against the backlit wave, looked African, and these were still the bad old days of apartheid. According to a story that accompanied the photo, a Hawaiian team, which included Eddie Aikau, had gone to Durban for a surf contest and had been barred from a whites-only hotel. I showed the Pipeline picture to Caryn, who, with my narration, studied the image closely. “He’s beautiful,” she said finally. Thank you.

• • •

SOMETIME IN OCTOBER, Honolua started breaking in earnest. The setup was the same one we had surfed in the spring: long outside wall with warbles and sections, then the big bowling section of the main takeoff, then a roaring blue freight train all down the reef, deep into the bay. It was, once again, a glorious wave, with hues in its depths so intense they felt like first editions—ocean colors never seen before, made solely for this wave, this moment, perhaps never to be seen again. To surf the place intelligently would require long study, clearly, an apprenticeship of years. But the Honolua local guild was no longer taking applications: the spot already had an outsized coterie of devotees. They came from all over Maui and, on big swells, from Oahu as well. The crowd at Honolua had more dark faces than Lahaina lineups did. In fact, not many of the regulars from the town spots appeared out there once the winter season got under way. The surfing was of a much higher caliber. At times, particularly when a swell was peaking, the action in the water felt completely frenzied as amped, excellent surfers pushed their limits, wave after wave, and pushed each other. It was a tough crowd. Nobody gave a newcomer a wave. But successfully picking off sweet ones was less a matter of pure dogfight aggression, I found, than of getting into the rhythm of the sets and of finding the seams in the crowd. The whole scene had the feeling of a religious shrine overrun by passionate pilgrims. I half expected people to start speaking in tongues, to flail and foam at the mouth, or monastery monkeys to bomb us with guavas.

The top guys were astonishing. Some were big names from the mags, some were local hotshots. I saw Les Potts out in the water only once that fall. He was riding a wide white board the same shape as mine. The surf was midsized, the wind light, the crowd pretty bad, and Potts stayed away from the pack at the main takeoff. He lurked instead on the inside, and used some form of advanced personal marine radar to dodge the sets and slip across the reef at improbable moments to catch large numbers of clean, fast waves that nobody else saw coming. His surfing was subtle and sure, and radical only when he saw the right moment—which did not by any means occur on every wave—to unleash some fierce maneuver. His knowledge of the reef appeared to be encyclopedic, and he concentrated on tucking himself into spiraling barrels over the shallowest inside slabs. I moved far down into the bay to watch him. The usual mob on the cliff, having come out to watch the show, couldn’t even see Potts, I realized. He was down around the corner, basically surfing alone.

My new board worked well. Watching Potts, I could see what he had in mind with the shape. I would never surf with such precision, but I found I could draw rounder lines, sharper curves, going higher under the lip than I would have thought possible on a racetrack wave like Honolua. Surfing hard, putting my board up on edge, also put other people in the lineup on notice that I was not out there to watch them surf. It was a long trek up the pecking order, and I would never reach the first rank, but I began to take a place in the second rank. On certain days I was catching as many waves as anyone, and people I didn’t know were even hooting me into drops—encouraging me to go hard. If my surfing had plateaued when I was fifteen, it was now on a new upward track. I probably couldn’t ride small Malibu any better now than I had as a grommet, but the size, speed, and soul satisfactions of Honolua Bay were greater by orders of magnitude than any spot I knew in California, even Rincon, could offer. The wave was far more intimidating, for a start, as well as more rewarding. And my obsession with it was well timed, given how badly my life on land was going.

Caryn took up with Mike the glasser. I couldn’t believe it. She told me to call him Michael. He was nicer, smarter than I knew, she said. They even turned up at Honolua together, in his shit-brown van. She sat on the cliff while he paddled out. It was windy and big—one of those rip-roaring, high-amp days. I had been in a wave-catching, mindless groove. Now I sourly watched “Michael” paddle cautiously up the bay. A set rolled through and he headed for the horizon. He was, I realized, a kook. That improved my mood. I went back to work, battling the scrum in the main bowl, intent on center stage. Maybe, if Caryn saw me ripping on the board she gave me—or at least surfing competently—she’d come to her senses and take me back. After making a high-line screamer that no one in west Maui could possibly have missed seeing, I looked for her on the cliff. But the shit-brown van was gone. Michael had somehow reached shore alive, evidently. That seemed both improbable and unfair.

• • •

TOWN WAS FLAT. The whole island had been flat for a week. I had the day off work; Becket had some acid. We dropped (that was the strange, sinking, truncated phrase people used for ingesting LSD) before daybreak, then stood around a fire in Kobatake’s backyard and waited for dawn. Old Kobatake never seemed to sleep. He jabbed the fire with a crowbar, his face a golden oval against the velvety blackness of his yard. He cackled when Becket joked about the roosters waking up his wife. Maybe our scheming, bewhiskered landlord wasn’t such a bad guy. We took my beflowered car, the former Rhino Chaser, and headed north.

Our plan was to trip in the country, away from the madding town, until our madness subsided. Out past Kaanapali we saw the sun’s first rays strike, extra-softly, the crenellated battlements of Molokai’s highlands across the channel. There was a faint reddish haze in the air—from cane fires, probably, or maybe it was volcanic smoke drifting up from the Big Island. Maui people called it vog, which seemed such a bad coinage that we laughed ourselves sick. Then Becket noticed, out on the ocean’s surface beyond Napili, a weird corduroy pattern. It was weird partly of its own accord, like everything else that morning, but mainly because it was so unexpected. It was, in fact, a huge north swell, steaming past the west end of Maui. Not a trace of it was showing in Lahaina. I found I couldn’t catch my breath. I couldn’t tell whether I was thrilled or frightened. I put the car on automatic surf pilot. It carried us swiftly down red-dirt roads through pineapple fields to the cliffs above Honolua.

The swell might have bypassed the bay if its angle were a bit more easterly. But it was swinging massively around the point, with sets breaking in places I had never seen waves break before, filling the whole north side of the bay, the entire arena we normally surfed, with whitewater. There was nobody around. I don’t remember much discussion. We had our boards on the roof. We were both hardwired to surf when there were waves. We waxed up and tried to study the lineup. It was hopeless. It was chaos, unmappable, closing out, and we were now tripping heavily. Peaking, as it was said. At some point we gave up and clambered down the trail. I picture us both giggling nervously. The roaring down on the narrow beach was constant, operatically ominous. I was sure I had never heard anything like it before. The bad news, some remaining rational part of me knew, was the good news. We would never make it out. We would be driven back onto the sand, quickly defeated by the multiple walls of whitewater stacked against us

We launched from the upper end of the beach, in the lee of some big rocks. It wasn’t a wise place to enter the water, normally, but we wanted to stay as far as possible from the bluff at the other end, which had a cave on its upcoast flank that ate boards and bodies on nice days, and was now being battered nonstop. We started paddling, scrambling in an eddy alongside the rocks, and then got swept counterclockwise like ants in a sucking drain, out into the broad field of big walls of whitewater. Struggling to hang on to my board, I lost track of Becket. My thoughts turned toward survival. I would spin and try to catch the next wall of whitewater, then try to hit the beach above the bluff. The imperatives were suddenly simple: stay out of the cave, don’t drown. But no whitewater presented itself. I was being swept sideways across the bay, past the bluff, paddling over the shoulders of big, foamy waves. This was apparently a lull between sets. I kept paddling toward open ocean. The bad news had turned good, which was bad. I was going to make it out. Becket, for his sins, also made it. We paddled far outside, into sunlight, stroking over vast swells still gathering themselves for the apocalyptic festivities inside the bay.

Our colloquy, sitting out in the ocean on our boards, would have seemed incoherent to an onlooker, had there been one. To us it made perfect, fractured sense. I remember lifting double handfuls of seawater toward the sky and letting them cascade through the morning light, saying, “Water? Water?” Becket: “I know what you mean.” I had dropped acid probably six or eight times before, and had usually had an awful time. The drug tended to reduce me after a while to molecular fascinations. These were okay as long as they stood at a certain angle to everyday perception, revealing its hilarious pomposity, its arbitrariness—this was the great promise of psychedelics, after all—but they were less funny when they locked into personal psychodramas, actual feelings, much distorted. Domenic had once had to carry me to a nurse we knew to get me pumped full of Thorazine, an antipsychotic, after I fell down a rabbit hole of guilt about deceiving my parents about my high school pot smoking. Caryn liked to say, quoting Walpole, that life is a comedy to those who think, a tragedy to those who feel. That pretty well nailed my problem with LSD. The cerebral part was terrific; the emotional part, not so much.

With this huge swell, the Maui surf grapevine worked faster than it did the first time I rode Honolua, when Domenic and I caught that modest new swell by camping there, and nobody turned up all morning. This time cars started appearing on the cliff not long after Becket and I got out. Nobody joined us, though. We must have looked like what we were—two fools, having made a major mistake, bobbing way beyond the waves, too scared to move in. The surf was much too disorganized to ride. Maybe it would clean up later. My fear, however, was not the usual, frantically calculating kind. It came and went, while my thoughts bounced between the troposphere and the ionosphere, with occasional swooping Coriolis detours down to the sea surface heaving beneath us. I knew I wanted to be back on shore, but couldn’t seem to hold that thought long. I began to edge in toward the point, having a vague idea that I could catch a green express train there, bound for dry land. Becket watched me recede with an expression of puzzled concern.

My Potts was not a big-wave board, but it was a fast paddler. I soon found myself in front of a broad green wall sweeping around the point and crisscrossed by backwash coming off the cliffs upcoast from Honolua. I was by then straight out from an area where people surfed on good days, although I had never surfed there myself—it wasn’t the classic spot, but the outer point, where swells first entered the bay. One of the backwash warbles ghosting across the big green unbroken face spoke to me. It was my door. It was a small tepee of dark water moving sideways across a huge wall of water headed shoreward. It would form a pocket of steepness where a small board could catch a big wave early. I turned and chased it. We met in the spot I envisioned. While the big wave lifted me unnervingly, I caught the small wave cleanly, jumped to my feet, and rode it over the ledge, down the big face, nice and early. The paradox did not end there. Although this was probably the biggest wave I had ever ridden—a bit hard to tell, on LSD—I surfed it like a small wave, making hard short-radius turns, never looking much beyond the nose of my board. I was completely involved in the sensations of turning—“entranced” would not be too strong a word. I might as well have been skateboarding, at an unusually high speed, when in fact I was trying to connect the outer point and the classic takeoff bowl, riding all the way through, something I had heard about but never seen done, and I probably had the wave to do it on. As it was, I arrived at the bowl, or at a very big bowl section directly out from the usual takeoff spot, still on my feet. I failed completely, however, to draw the shoreward line, to make the charge toward the bottom that might have let me keep going. Instead, I carved up the face and under the lip, still hardly looking beyond the nose of my board. I got launched, my board drifting sadly away from my feet as we fell awkwardly through the air together.

I must have got a good breath, because the wave beat me viciously and long but could not convince my body to panic and suck water. I took several more waves on the head, diving deep and feeling myself get swept into shallower water. Soon I was being thrown against the rocks on the downcoast side of the bluff. I got a handhold and clambered out of the water, but climbed only a few feet before sitting down to inspect my shins and feet, which were battered and bleeding. A wave swept me off my perch. Incredibly, I did the same thing again a few waves later. I couldn’t seem to grasp that I needed to get higher up the cliff, onto dry rocks. The third time I scrambled up, a kind man who had climbed down the cliff to help grabbed me by the arm and escorted me to higher ground. I was too tired and disoriented to speak. I made my thanks known by sign language. I also inquired, by pantomime, about my board. “Went in the cave,” he said.

I decided to take a nap. I climbed the cliff, ignored the stares, found my car, got in the backseat, and lay down. Sleep wouldn’t come. I flew out of the car, increasingly disoriented. I looked for Becket. He was still out there, halfway to Molokai, still alone. I decided to go down to the innermost part of the bay, where the ocean was always calm, to wait for him. Caryn and I had used to picnic there. You had to walk through creek-bottom jungle from the road. But I decided to drive. Somehow I crashed the old car through the jungle to the beach. But then the beach didn’t feel safe. There were very tall coconut palms, and falling coconuts were dangerous. I waded out into the water, up to my chest, but still felt the threat of coconuts. I decided to go see Caryn at the ice-cream parlor in Kaanapali.

She seemed surprised to see me. I was still using sign language. She asked for a break, and took me outside to a small, round table. She set a sundae glass filled with water in front of me. The morning sun seemed to concentrate all its brilliance inside the water in the sundae glass. Staring into it, I could see Puu Kukui floating upside down in the sky. I told Caryn, inside my head, that the water in Honolua Bay was no longer clear, the way it had been when we snorkeled there in summer, that it was now all stirred up and murky. She took my hand to show that she understood. I told her, still inside my head, that we would find her father. She squeezed my hand. Then I remembered that I had left Becket in peril, and that I had never found my board. I found my voice and said I had to go. She did too, she said, nodding toward her place of work. “Hana hana.”

“Humuhumu.”

I set off again for Honolua. On the side of the road, near the Kaanapali entrance, Leslie Potts was hitchhiking. I stopped. He had a surfboard and a guitar. I didn’t seem to be imagining this. He slid his board into the car, on the passenger side, and sat directly behind me. I drove on. He began to pick out little bluesy riffs on his guitar. We started seeing lines out at sea, marching south, from the swell. Potts whistled quietly. He hummed a few bars, sang a few lyrics. He had a keening, breathy singing voice, well suited to country blues. “How’s the board?”

“It went in the cave.”

“Ouch. Did it come out?”

“Don’t know.”

We didn’t pursue the matter.

Back at Honolua, I saw that there were now a dozen guys in the water, and a dozen more waxing up. The surf looked far more organized than it had earlier. Still huge. I parked and hurried to the beach trail. Sitting on the rocks far below, his board beside him, was Becket. I made my way down. He was relieved to see me—not angry at being abandoned, as I expected. If anything, he seemed abashed, preoccupied. Then I followed his glance to a mangled board sitting propped on the rocks behind him. It was, of course, mine. I went over to it. The tail was smashed, the fin snapped off. There were too many dings to count. A flap of fiberglass hung from the underside of the nose. It could all be fixed, Becket murmured. It was amazing it hadn’t snapped in half. I wasn’t amazed. I felt light-headed and ill, inspecting the damage. The board would never be the same. Becket directed my attention to the lineup, where some of the local heroes were starting to perform. The swell was dropping, the surf improving. Becket, whose board was undamaged, paddled back out.