When the wall of windows glazed with first light, the birds rustled, wings against wire, and stretched their scaly toes from wooden perches. The robin un-tucked his head, and with short shakes, ruffled his feathers. An aging Inca dove scratched at the newspaper lining his cage. A starling, in white-speckled winter plumage, probed the air before his yellow beak, remaining to one side of the cage, not quite sure of the hollow space at the center. Six canaries lined themselves up on a dowel. Side by side, they preened pale yellow feather after pale yellow feather.

There were Bengalese finches, Brewer’s sparrows, cowbirds, yellow-headed blackbirds. Hundreds of zebra finches, housed four or five to a cage, hopped up and down, on and off perches. A male zebra finch landed in a food dish. As if surprised, he sat immobile for a moment before fluttering out once more, scattering seeds like shotgun pellets onto the floor. When he called, the others instantly erupted into a chorus of nasal mee mees, their small striped heads and orange cheek patches jerking right and left. Dissonant bursts, sounds understood only by them, perhaps meant to warn each other or appeal to drab females nearby.

On the floor a white picnic cooler served as a soundproof chamber. The white-crowned sparrow inside could not see the morning sun nor hear his fellow birds rustling, calling and hopping in the brightening laboratory. He knocked his beak against the plastic wall and let out a short whistle. The sound was followed by silence. He pecked at a seed. He flew up to his perch. He cocked his head to one side. Conscious of the limits to his auditory space, the fact that nothing could hear him, he sang again and listened to the whistle, buzz and trill of his own, five-note song.

From the hallway, David heard the muffled chirps of birds. He inserted a key and pulled on the heavy door. When he flipped on the lights, the birds responded with an urgent burst of sound. The laboratory turned from night to day. Silence into song. Each morning began exactly the same way. Birds beckoned him. Light and chorus marked his arrival.

He put down his briefcase, rolled up his sleeves and set to work, taking his time going from cage to cage, ensuring that each bird was okay. He stopped in front of the Inca dove, opened the cage and took hold of it. The dove, which had been hand-raised by Sarah, settled easily into his palm, its small black eyes staring back at him with unusual calmness. David rubbed his finger lightly on its breast and then set it free on the counter. The dove flew up, perched on a light fixture and let out an almost inaudible call, one that had always sounded to David like “no hope, no hope.”

He glanced at his watch. He had an hour to clean before he was due to teach the first class of the semester. Pulling the water and food trays from the first row of birdcages, he filled the sink with soapy water and began to scrub.

Outside the window, the winter morning had brightened. Beyond his own reflection, he saw a flock of waxwings swoop up the hillside and land in a serviceberry bush. Seven, eight, maybe twelve plump birds, unmistakable in silhouette. Birds that settled into the valley during the winter months and then migrated north to breed in the spring, and odd for songbirds because male and female waxwings looked and sounded alike. Mirrors of one another. In most birds, the males sang and the females listened, deciding which male song sounded best. Singing was a sex-specific behavior traced to brain wiring, to physiology, to ecology and evolution. It made sense, except that in waxwings it wasn’t that way. An exception that remained unstudied.

David filled the now clean containers with water and seed, slipped them back into the cages and pulled another set from the next row. With his upper right arm, he leaned in and brushed a curl of his long hair away from his eye. Over running water and background calls of hungry finches, he could hear Sarah’s voice. Fundamentally, you’re shy. Not exactly insecure, but there’s a curve to your chest, a shyness imprinted along your upper back. He rolled his shoulders back, stood up straighter. You blush easily. I think it’s why you keep your hair long.

He felt the low-grade pounding in his head, the pulse and thud of a persistent headache that had been with him for some months now. The comfort he’d once enjoyed at being known so well by Sarah had switched to irritation and uneasiness whenever he heard her voice in his head. Had she never considered the possibility that he was too busy to remember to make hair appointments? Couldn’t there be a practical explanation, rather than an underlying emotional or psychological reason, for his longer hair? He finished the morning routine, collected his computer and hurried off to class, the sound of birdsong fading as the lab door swung shut behind him.

Though shy, David was a master teacher. In front of a class, he found it easy to cultivate a lively persona. He began the lecture by projecting images of a human baby and a bird chick. “These two might not look similar, but songbirds are very much like humans,” he said. “They both develop learned vocal communication and they do it in a similar way. Like humans, baby birds first listen. Later, they babble. Finally, they learn to sing.”

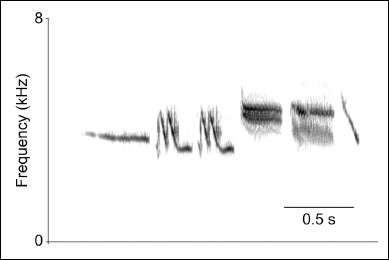

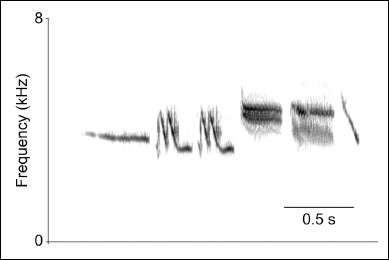

He played a recording of a bird learning to sing. “Listen and you will hear these sounds changing from a kind of babbling to a fully developed robin’s song.”

In the early years, David had managed remarkable success. He’d been the first to poke through a bird’s skull and insert fine wires into single neurons, a technique that allowed him to survey a new landscape, mark the places on a brain that could, and did, acquire a type of language. When these antennae-crowned birds sang, the sounds and electrical impulses were recorded. Numbers were sifted through software programs, analyzed and written up into scientific publications. He was called a pioneer and received grant after grant. His technique, now used internationally, allowed scientists to listen in on the unconscious thoughts of birds, the neuronal firings that triggered song. Songs, although he would never say it out loud, that might be a proxy for love.

He moved the class through the basics of birdsong, explaining the difference between calls that all birds made instinctually, and songs which they learned after hearing the males of their own species singing. And birds, too, had dialects. A white-crowned sparrow in Washington State had a different accent than one in Colorado. He told them that like humans, an isolated bird with no hearing could never learn to sing. And, like humans, if a bird went deaf later in life, it would lose its song just as deaf humans lose their ability to speak.

“When you talk your brain is paying attention,” he said, “comparing how you sound to a template for how you should sound in your head. If you lose the auditory feedback, you eventually lose your speech.” He played recordings, showed slides, paced across the lecture stage, answered questions, and then the hour was over.

“What’s the take-home message today?” He paused for emphasis. “To communicate with others, you must be able to hear yourself.”

After class he passed by the main office to retrieve his mail. There was a memorandum about a recent theft at the institute, another about a group of animal rights activists in Oregon. More and more sophisticated security measures were becoming necessary. Everyone was supposed to keep their lab doors locked at all times. Of course, there would be increased fees charged to researcher grants to cover these extra costs. Terrific. More overhead would be taken from his dwindling grant. He dropped both flyers into the recycle bin and then flipped through the table of contents of the new Neuroscience magazine. Cell, cell, cell. Reductionists, all of them. Searching for the smallest denominator possible, they wanted to find “the” cancer gene, “the” secret to cell-cell communication, or the holy grail: “the” memory engram.

Almost every neuroscientist dreamed of unraveling memory, of finding out where memories were stored. Back in the 1920s, the behaviorist Karl Lashley had come up with the word “engram” to name the place where he thought he would find evidence of memories imprinted on nerve cells. As if memories could be exposed like a photographic image on film. But so far, no one had found the physical engravings.

David rolled the magazine into his fist, clear on the fact that cell or engram, his lab had produced nothing for many months. The rate of success he’d enjoyed the past decade had abruptly decelerated. Shrinking research funds had forced him to let the animal care technician go. He had no undergraduate or graduate students, and was waiting for the arrival of a new post-doctoral fellow. Whereas before, his lab bustled with post-docs, graduate students, undergraduates and animal care technicians, now he was alone with no new resources in sight. How had the “Decade of the Brain” passed so quickly?

Ten years earlier, he and other neuroscientists had successfully lobbied Congress for funding, making the case that although the brain was composed of a hundred billion neurons, it could be and would be understood. Signal molecules had been retained throughout the millennia of evolution, they said. Electrical impulses and nerves connected all living beings. The brain was electricity. You flip the right switches, sections turned on. Flip other switches, and sections turn off. Everything that ails—Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, Huntington’s Chorea—not to mention drug addiction, epilepsy, even problems with speech, hearing and perception, could be cured if they understood the brain.

They promised to cut open the skull and tease meaning from pink fatty tissue. Studying neurons, they assured Congress, would allow them to create navigational maps much like early explorers did for Africa, the Amazon and the Arctic, maps that would help people find their way inward, from behavior to nerve to gene, helping them grasp the most elemental understanding of themselves and the sentient world. If nerves were like yarn, they said, they could loosen the skein, untwist the knots, find the beginning.

Congressional support was bipartisan: the brain and its diseases had no political enemies. A bill was passed and the president signed the “Decade of the Brain” into existence. Neuroscientists, buoyed by their swollen budgets, worked overtime in an exhilarating combination of collaboration and competition. Europe responded to the American investment with its own brain focus and everyone benefited from the increased funds, arriving early to work and trying to stay later than their competitors.

David became famous in those first years for teasing apart and piecing back together how a bird sang. He and his students showed that they could follow a molecule of air as it entered the nostrils and traveled down the trachea into the air sacs tucked behind a bird’s lungs. They figured out which nerves attached to which muscles, how the muscles expanded and compressed those air sacs like the bellows of an accordion, and how the sacs pushed breath out past the flaps of the syrinx to become waves that made sound. Their work was published in Science and Nature and every paper was celebrated with champagne, but unlike other laboratories, there were no cork dents in the ceiling, no uncontrolled frothing or spilling of cheap bubbling wine into plastic tumblers. In David’s lab, glass flutes were poured to perfection, a dry tangy drink to be savored, not gulped, a reward for good solid work, clever experiments, nifty techniques, and determined scientists. And always, they toasted the small, resilient singing birds.

Lately there had been no such successes. In the past eighteen months there had been dead birds and dead ends while the expiration date on his remaining grant advanced. There was an Italian post-doc set to arrive in a month and David hoped he’d be worth the balance of the funds. He walked faster down the hallway. If he didn’t have some sort of break through soon, he wasn’t going to be doing any research at all.

Back in his laboratory, he heard ringing and passed quickly into his office. The throb in his head had not lessened. As he leaned for the phone, he glanced at the caller ID and saw a jumble of numbers span the screen. An international call. Possibly Sarah. Probably Sarah. He let go of the Neuroscience magazine and it sprang open on his desk. He reached for the phone and then stopped, his hand hovering above the receiver. In the laboratory, a zebra finch tooted and a starling whistled. The ringing continued two, three, four more times and then it stopped.

He opened the top drawer of his desk and took out a bottle of aspirin. He popped the top, shook out two pills and swallowed them hard without water. He sat down at his desk and stared at the large glass jar of armadillo fetuses that Sarah had given him as a present. Four white armadillos with ridges on their backs, eyes closed, suspended in fluid, connected by a single umbilical cord, never to become adults. The babies we won’t have. Sarah. At every moment. Sarah. He closed his eyes. In twenty minutes the aspirin would be working, taking the edge off the pain. Thoughts and memories weren’t as easily dulled.

“It’s not as simple as that,” Sarah was saying. They were in their graduate school apartment in Louisiana and she was leaning against the armrest on the couch with her left leg bent, the other sprawled over David’s thigh. The evening was muggy and the rotating table fan did little to dry the perspiration beading on her tanned skin. Ed, their roommate and best friend, sat across from them on the wooden floor, back against the wall, his arms resting on his knees, a bottle of beer dangling from one hand. The room was mostly dark, only a pale fluorescence from the kitchen illuminated half of Ed’s face.

“Who said it was simple?” David asked.

“You did. You said there’s a signal, there’s a receiver, but…”

“That’s not the same thing as saying it’s simple,” Ed said. He set his beer down and pulled his long damp hair back into a tight ponytail at the nape of his neck and then took up his beer again.

David looked at Ed—bearded, rugged—and then back to Sarah. They’d been talking and drinking since dinner and now it was nearing midnight. Tomorrow Ed would be leaving again for four months in the tropics and neither David nor Sarah was anxious for him to go.

“All I’m saying is that signal and receiver are only part of communication, and only a small part at that. It’s more about collaboration.”

Both men took sips of beer, waited for her to keep going. Each loved it when she was like this, slightly drunk, excited and argumentative.

“Collaboration?” Ed said.

“Yes. Collaboration. And context and perception. A signal, or the perception of a signal out of context is meaningless at best, confusing and problematic at worst.”

David looked over at Ed. “I told you. Beware of a formidable woman.”

Sarah kicked David in the thigh with her heel. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

“Everything,” Ed answered. And then, looking straight at Sarah, “And… that he’s in love with you.”

Sarah rolled her eyes. David held his beer bottle up to the light and realized it was empty. “Last round.” He lifted her leg from his thigh, stood up to go into the kitchen. “Sarah?”

She shook her head no.

“Ed?”

“Of course.”

From the kitchen David heard Ed say, “And you intimidate him a little.”

“Don’t be absurd,” Sarah said.

Two days after Ed left Sarah came home late from the clinic and found David sitting on the couch surrounded by papers about birdsong. Immersed in a new research topic, he barely glanced up.

“Do I intimidate you?”

David looked up. She stood in the doorway, hands on her hips, thin arms jutting out at the elbows like a cormorant drying itself after a dive. “Terribly.” He turned the page on the manuscript he was reading.

“Ed’s full of shit.”

Sarah sat down next to him on the couch. David put his papers to the side.

“You’re not serious are you?” he asked.

“Haven’t you noticed that we talk more when Ed’s around?”

“Of course. Three mouths versus two.”

“No, I mean you and me. You talk more when he’s here.”

“That’s ridiculous.”

“I think we’re more honest with each other, too, when he’s around.”

“We’re always honest.”

“Are you?”

“It’s just,” he hesitated and smiled, “let’s just say I’m the opposite of a male bird. You sing. I listen.”

David hadn’t truly stuttered as a child, but as an adolescent he’d shown a lack of fluency when it came to putting emotions into words. His parents had assumed their son’s muteness in the face of feelings had more to do with teenage lethargy than anything else. It wasn’t until he met Sarah that he’d learned there was a name for his condition.

They lay in bed one night. “Alexithymia,” she said.

“What the hell is that?”

“Difficulty identifying feelings and describing them to others, lack of fantasies, operative thinking while appearing to be super-adjusted to reality.” She twisted a curl of his hair around her finger.

“So now people who are well-adjusted and don’t feel the need to blab about their feelings all the time have disorders?” But he knew she was on to something and was glad that the room was dark. He didn’t know how he felt about being seen so clearly.

“It’s not in the DSM as a disorder. It’s a personality trait. Patterns get set when you’re young. It’s like one of your birds that has learned to sing. You say that he’s crystallized his song, don’t you? Once he learns it, it can’t be changed.”

He felt her lips on his neck, her hand caressing his arm.

“It’s not severe, but noticeable. I think it’s why you gravitated towards nature and birds.”

Sarah was probably right. David had discovered his ability to hear and identify sounds the way some children learned they’re good at throwing a baseball. Bird watching gave him permission to be alone, a sense of exploration, emotions that didn’t require explanation. From the earliest time he could remember, whenever he heard a sound, he was drawn to its source. Whether it was a bird, insect or squeaky faucet, he listened, made a mental note, and then he never forgot the sound again. At eight years old, he was explaining to his mother the differences between bird, chipmunk and squirrel sounds. By ten, he could identify over fifty species of birds, five or six mammals and a good number of insects. On his twelfth birthday, his parents gave him a microphone and tape recorder.

As a teenager, he walked every morning before school through the wooded area behind his house. Setting out, his heart rate rose in anticipation of what he might see or hear. There was the feeling that he was sneaking up on something mysterious, seeing what no one else was seeing, hearing what others couldn’t understand. The world was a detail of sounds, and every year that world became more interesting, the soundscape more complex, his ability to hear subtleties more refined. He learned to distinguish a young robin from a seasoned singer. A mockingbird that migrated to Florida from one that flew instead to Costa Rica. People were impressed, but really it wasn’t so hard. Mockingbirds imitated songs from other birds, and only migrants to Costa Rica picked up songs from other Costa Rican birds. Before David met Ed, he didn’t know there was another like himself.

The next day Sarah went to a pet store and brought home a parrot which she named Skinner. When David came in from the laboratory, he found her assembling a five-foot cage in the kitchen. Her long brown hair, parted in the middle, hung over her shoulders and covered her face. The bird, nervous in its new surroundings, paced left and right on a perch.

“What’s this?” David asked. “A substitute for Ed?”

“Just making sure you keep talking,” she said over her shoulder.

David eyed the bird.

“He’ll grow on you.” She reached out and the parrot stepped onto her hand. She placed him in his new cage and turned to kiss David.

“Truth is,” she whispered, “I’m glad you don’t go off into the forest like Ed.”

David wondered whether she was just saying this for his benefit. What did she see in him when there were other men, ruddy and fit, smart and adventurous, like his roommate? He felt her fingers at his waist, unbuckling his belt. He slipped his hands underneath her tank top and let his fingers move across the waves of her ribs to her breasts. Her personality defied the slightness of her body. He knew he was slow to put words on his innermost feelings, knew he wasn’t the best conversationalist, nothing like Ed who could charm a group with his stories of the tropics. The parrot let out a squawk. He hoped he was enough.

“Like I was saying the other night,” she said between kisses. “It’s a lot more than signaler and receiver. It’s about context, perception and collaboration.”

A week into the semester, David returned from lecturing and found a young woman with bright red hair at his laboratory door. “Waiting for me?” Clearly, she had disregarded the sign in the stairwell that read: Researchers only. No students allowed.

“Yes. I’m in your class.” She fidgeted with her hands. “I want to work in your laboratory.”

He laughed at her forwardness. “What’s your name?”

“Rebecca.”

“Rebecca, I’m sorry. I’m not hiring, but come on. I can suggest other people.” He scribbled the names of two labs that he knew were in need of undergraduate help, and could afford it, and handed her the paper, but she shook her head.

“No, I really want to work in your lab.” She had a small diamond piercing in her nose.

“Why?”

“You said it in class, you know. Birds can tell us about the beginnings of language.”

The diamond glinted in the sun when she turned her head and her blue earrings matched her eyes.

“It’s more than that.” She was flustered. “They fly and sing and nest and seem, I don’t know, unbounded in the ways we are.”

“Unbounded?” It was an interesting thought, but at the end of it all, he could have told her, everything was bounded and bounded in exactly the same way. “Really, I appreciate your interest, but I truly don’t have any projects for undergraduates right now. I’d be happy to suggest some reading material to you.”

“I don’t mind what kind of work I do.” Her neck and face flushed red, and when she turned her head, there was the glint of her piercing again. “I’m drawn to them.”

Her honesty and vulnerability were charming. If only more undergraduates could be so moved. He wished he actually had research funds; certainly he could use the help. “That’s a sentiment I can relate to. I’ve always been drawn to them too. I promise to call if anything comes up.” But the paper on which he took down her number was promptly buried by other papers on his desk. For the next week he noticed her in the back of the auditorium listening attentively to his lectures, scribbling notes. Once again, she returned to his laboratory.

“You do get points for being persistent,” he said. He unlocked the door and they passed through his lab and conference room into his office. He moved a stack of papers from a chair and motioned for her to sit down.

“I just wanted to say,” she said. “I mean, what you said in class today.” She looked at her notebook and read: “Speech is a river of breath, bent into hisses and hums by the soft flesh of the mouth and throat.” She looked up at him. “That’s so poetic.”

David didn’t tell her the sentence wasn’t his, but Steven Pinker’s, a much more famous scientist.

“And you said, Birds might reveal the secrets of communication.”

Anyone who paid that much attention in lecture had the potential to be good in the lab. “Ok, you’ve convinced me. I’m putting you on the payroll.” He would ask the institute’s director for emergency bridge funds if it came to that.

A short time after she began working for him, he learned she wasn’t a student.

“So what were you doing in my lecture?”

“Crashing the course.”

“Why?”

She paused, as if unsure how to answer. “Like I said, I like birds. I’m drawn to them. I looked you up, was taken by what you’d written on your webpage. I thought your work looked fascinating.”

“You lied?”

“No, I never said I was a student, only that I wanted to work here.”

During the next few weeks David taught Rebecca to care for the birds. He taught her how to properly scrub their cages, how to give them the right amount of food, which supplements to use with different species. The zebra finches were fed peas and boiled eggs every other day. The robins, starlings and white-crowned sparrows got crickets. He showed her how to hold a bird in her palm, with the head between her second and third finger.

“Too firmly and you hurt the bird. Too lightly, and it will escape your hand.”

He stood beside her as she learned to put the colored identification bands on the birds. “Go palm up, it’s easier,” he said.

She turned her palm up and with a forceps slipped a red band around the bird’s ankle.

“That’s it. You’ve got it. Now squeeze the band completely shut with these pliers.”

She looked up when she finished.

“Well done. Now let’s do a few more.”

The thin pencils she used to hold her hair in place on the top of her head stuck out like misplaced chopsticks. It made him think of an African grey-crowned crane. Food for the eyes, Ed called it after his trip to Kenya. David remembered Ed saying, In west Kenya, I stayed with an African doctor who runs a small farm, does everything from making methane fuel from cow manure to gravity-fed water systems and organic vegetables. He had a couple of gray-crowned cranes too, loose on the property grazing back and forth in the grass between the cows, and when I asked him why he kept the birds, he said: “People don’t just need food for their stomachs; they need food for the eyes.”

Yes, food for the eyes. Rebecca was beautiful. There was a vibrancy about her, a confidence in the way she carried herself, though a distinct judiciousness to her speech. In the short time she’d been in the lab, she was proving to be a willing student, meticulous in bird care, always on time, all about the business of work, but she didn’t speak unless spoken to. As he stood next to her, he had two rapid, unrelated thoughts. She’s like a bird, and her quietness is unsettling. He didn’t know what to make of these thoughts. Was chattiness in humans tied to biochemistry? Recently, researchers in the Netherlands had shown that when injected with testosterone, the females of some bird species would begin to sing.

Regardless of her quiet nature, David was grateful that by the time Anton, the Italian post-doc, arrived in four weeks, Rebecca would be fully trained. David would orient Anton to the laboratory, the surgery techniques and the experimental protocols. By the end of the first month, with Rebecca’s clean, organized cages, and a new set of birds, they would be ready to begin a series of intensive experiments.

David’s conference room was really a library. There were hundreds of books on every shelf, as if he’d collected any title that included the word “bird.” Rebecca liked to spend time in the room, pulling books from their places, flipping through the pages and reading bits of information here and there. She was particularly drawn to the older volumes. She reached up on her tiptoes and took down one that looked quite old. The Zebra Finch: Notes on a Model Bird. She opened it to the beginning and read.

In the dry central grasslands of Australia, the small finch, Taeniopygia guttata, lives in colonies of one hundred birds or more. Gregarious and boisterous, these birds can be easily identified by even the casual naturalist. Their upper bodies are gray, their bellies white. The tail is striped black and white, presumably giving the bird its name. Males are distinguished by rust colored cheek patches behind each eye. Both sexes have bright reddish-orange beaks and legs.

Zebra finches feed in flocks, landing in one large swooping motion onto the ground, picking at fallen grass seeds, and occasionally, small insects. At the slightest noise or commotion, they rise as one and flutter back to the trees to empty their crops. Among them, there is an almost constant chorus of “tet tet” calls, resembling the beeping of a group of children softly tooting toy trumpets.

In the field, they say, birds pair for life and both males and females care for the young. In the field, they breed from October to April, the females selecting nest sites, the males gathering the dry grasses and sticks that the female then uses to construct the dome-shaped nest. In the field, a female lays three to six eggs per nest. After two weeks, the eggs hatch and featherless pink chicks are born. At five weeks of age, the nestlings leave home.

First, the zebra finch was collected because it was pretty, then, because they could be kept in captivity, breeding readily in a cage at any time of the year. They are easy pets and reasonably amusing companions to the curious naturalist. These birds are resilient and of great use to the experimental behaviorist. Bluntly put, one can accomplish a great number of experiments with the zebra finch and it will not die.

She flipped to the beginning to check its publication year. 1952. She shut the book. Australia. The birds were not even on their original continent. She wondered whether they knew this, or could sense it. They seemed happy enough in the lab but they would probably be happier if she stopped reading and gave them their morning peas and eggs.

During the first days, when Anton, the post-doc, arrived at the laboratory, he found Rebecca in the routine of feeding the birds. Zebra finches, flitting on and off their perches, chattered loudly, scattering seed onto the floor. There was the beating of wings against the wire cages, trills of canaries, high-pitched whistles from the starlings, and the sound of birdseed, like the frozen snow outside, crunching beneath his shoes.

He unwound the orange scarf from around his neck, leaving it hanging over his shoulders while he unbuttoned his overcoat, took if off and hung it on a hook over a lab coat that looked like it had never been worn. His body was warm, glowing from the past hour he’d spent in the gym. The scar on his left cheek, usually imperceptible, stood out as a series of small white traces after exercise.

He’d been sixteen, sitting in the living room tightening a guitar string. When he plucked it, the string snapped and hit his face just shy of his left eye. He sat stunned for a moment before he raised his hand and came away with a smear of blood. Setting the guitar aside, he went to the bathroom, washed, and then he stared into the mirror to study the damage. The string had slashed him at the top of his cheekbone. Sound vibration forever imprinted on his skin.

That night at dinner he’d expected his mother to mention the mark, but absorbed in reviewing her newest photographs, she didn’t notice. Now the scar was only perceptible to those who came really close, or, he liked to think, like the dots and dashes of Morse code, decipherable only to those who bothered to learn.

“Grüß Gott,” he said, directing the greeting at Rebecca.

She turned to him and smiled. “That doesn’t sound like Italian.”

“It’s not.” Her eyes were blue and intent. Most Americans, he noticed, didn’t hold eye contact for long, but she wasn’t afraid to look at him.

“I thought you were Italian.”

“Südtirolean.” He didn’t break the connection.

She raised her eyebrows in question. “So what do people there speak?”

“German mostly. Some Italian. A few people speak Ladin too.”

“Latin?”

“No, Ladin. Another language.”

“I’ve never heard of that.”

“You’ve never been to Südtirol.”

There was a moment of hesitation. She looked away, clearly frustrated. “But which country do you live in?”

“Depends. We go back and forth, depending on the year, the war, the government.” The words didn’t come out the way he wanted. Though completely competent in English, his accent sounded harsh and cumbersome to his ear. Although he practiced at night, try as he might, he could not make his mouth and lips move properly around the English words.

“Which war?”

“The latest. World War II.”

She didn’t say anything before she turned back toward her work. Her red hair was twisted up on her head. A few strands curled around the nape of her freckled neck and he had the urge to reach out and touch them. He removed his blue and orange knit hat. Below, his dark hair was sheared short and even now, in his early thirties, thinning.

“I thought you were Italian,” she said.

“I am, half. My mother’s an Italian speaker, my father’s a German speaker. On the streets people speak mostly German. I speak both but I like German more.” He was aware of the fact that whenever he was in her presence there was a tingling on his skin and his English became even more self-conscious. More than once, he’d found himself thinking about her in the middle of the day.

“Your parents don’t speak the same language?”

Anton laughed. “Of course, they speak German together.” He’d never thought of it quite like that, but maybe language had been the fundamental problem between them. His mother had always insisted on Italian with him, which his father couldn’t understand. Her German, though fluent, always seemed strained.

He watched Rebecca slide the gates up and reach into the cages, one by one, pulling out the half empty, feces-coated plastic water containers. She drew out the seed containers too, tipping the hulls into the trash and then tossing all the containers into the large black sink for washing. The insides of her wrists, when she dumped the containers, flashed pale white, the deep blue veins underneath the skin visible for just a second.

She hesitated in front of a cage. “One of the finches has lost his band.”

Without the band, the bird would be useless for experiments, there’d be no way to keep track of his movements, no way to follow his song.

“Do you need help?” He moved to her side.

She shook her head. She raised the gate, inserted her hand. The four birds in the cage fluttered up and back, calling out against the intrusion. The entire laboratory of zebra finches joined in their anxiety. She cornered the band-less bird in her palm and removed him. The laboratory went quiet again. She snapped a blue numbered band around the bird’s twiglike leg, raised him to eye level and stared at him for a moment before returning him to his cage. The small finch perched for a second, immobilized, as if taking in both his freedom and the confines of his cage once more. He bobbed his black and white striped tail as he balanced on the perch. His eyes were glassy and alert and the orange cheek patches below them jumped with every twitch of his head as if he were still considering Rebecca, only now from this new vantage point.

Anton was close to her and wanted to say something, but what? That he was good at dancing, a better conversationalist in German, Italian or even French than in English? He looked at the birds. She was quiet like his mother. No need to speak when a nod or shake of the head would do. He opened his mouth, but then closed it again without saying anything. She turned to him and smiled and in that second, there was a flash of energy. He felt his face flush. He waited for her to say something else but she didn’t.

He turned away to focus on “Red 31,” the bird for that day’s experiment, the finch that was going to provide the data he needed to publish his first solid paper. He noticed that David hadn’t yet removed the food dish from the cage, which violated the protocol he’d been taught, and so Anton pulled the food. Full stomachs didn’t go well with anesthesia.

From the other side of the laboratory he brought a cage with female zebra finches and held it in front of the cage with “Red 31.” The bird hopped, puffed up his feathers and sang a half-hearted version of his song. “You won’t win any contests,” he said to the bird in German, “but you’re ready for your backpack.” He returned the cage of females to their spot on the counter.

Anton took “Red 31” into his hand, slipped a white, elastic belt over the bird’s head and around his chest, just below the wishbone, and then, one at a time, he slid the bird’s wings free of the belt. Later, electrical wires could be connected to this belt, and then threaded out through the top of the cage, plugged into transformers and computers to measure nerve activity and breathing. He finished positioning the backpack and then released “Red 31” to his cage again, conscious all the while of Rebecca moving around the lab and the fact that both of them were glancing at one another intermittently.

He flipped on the microphone and recorder and went back to the cage with female birds. When he slipped the gate up and inserted his hand inside, the birds flapped hysterically. He cornered one and waited while it fluttered up and down into his hand.

“Males,” he’d heard David say, “aren’t choosey. Any female will do.”

Anton returned to the cage with “Red 31,” raised the gate and slipped the female inside. The drab gray female perched next to “Red 31” and pecked him on the head. “Red 31” let out a single, half-hearted bleep, and hopped left and right. Anton took a step back. Single bleeps didn’t count. “Red 31” needed to sing a whole song. The female hopped to his side again. Another peck. The male leaned into her. She hopped away. “Red 31” quickly righted himself, and then, with a ruffle of his feathers, he danced right and left blurting a bout of song, a series of harmonic bleeps repeated over and over. Lines of data streamed across the computer screen.

Convinced that the bird was going to perform, Anton left “Red 31” and went through the conference room with its library of books to David’s office to tell him that the bird was ready for surgery. He found David leaning back in his chair, eyes closed, his feet propped up on the desk next to the large glass with the grotesque armadillo fetuses. A strange thing to have in one’s office and Anton wondered why David had them. And, a strange position for David, who usually was moving around or at the very least, banging the keyboard of his computer writing another paper or grant proposal.

“Good morning, David.”

David swung in his chair, as if embarrassed at having been caught in stillness. “Ah, Anton. Finally!”

Anton noted sadness in David’s face and glanced away out of respect. “”Red 31” doesn’t sing a lot, but he is ready.”

“Terrific. I’ll meet you there in five minutes.”

Out in the laboratory Anton prepared the surgical table and David recounted the article he’d read that morning.

“I’ll say it again,” David said. “There’s no evidence for the engram. Even Lashley, thirty years after he first proposed the idea, concluded that he could not find memory traces. I’m sure you read the paper.”

“Of course I read it, David, but Lashley also said in the same paper, that even with evidence against it, learning occurs and it has to be recorded somewhere. And Lashley didn’t have the modern tools of molecular and cellular biology that we have.” Anton could tell he was having little effect on David’s stubborn thinking. He put the scissors and forceps into the pot to be sterilized. “Besides, David, just because you don’t see something doesn’t mean it isn’t there.”

“Right, like God?” David asked. He turned on the sink water, waited for it to warm and lathered orange anti-bacterial soap in his palms, allowing the suds to travel up his forearms.

“No, like gravity,” Anton said.

David rinsed and dried himself with industrial paper towels before he slipped his hand into the cage and encircled the male zebra finch with his palm. He positioned the bird on the surgery table, his hands gently holding its head while it jerked into anesthetic sleep. He didn’t answer Anton.

“Or atoms,” Anton said.

David sat down, rolled the chair toward the table and focused the microscope onto the bird. Anton positioned himself at his side and together they began to work on the bird.

“Or sonar of whales,” Anton said.

“Whales?” David chuckled. “Definitely lots of atoms there and I can see them.”

“But you can’t hear them singing. Just because you can’t see it or hear it doesn’t mean it’s not there.”

“What’s an engram?” Rebecca asked.

David spun around in the chair, surprised by her voice. “Excellent question!” She was nothing like the previous technician who hardly managed to feed the birds and clean their cages and certainly never asked a question. “An engram is wishful thinking.” He swiveled back to the bird.

Anton turned to Rebecca to explain. “Engrams are…hypothetical.”

David interrupted him, “Hypothetical is right!”

“Hypothetical right now,” Anton said, “but theoretically, easy to model. They’re shape changes on nerves that store memory—basically, they are memory imprinted on nerve cells. They are something we think, with the right tools, we can see.” He turned back to David. “Engrams are why Stanley Sommers will win the Nobel Prize and you won’t even be invited to the ceremony in Stockholm.”

David laughed. “I hate aquavit and pickled herring anyway.” He placed his eyes over the oculars of the surgical microscope and focused closer in on the zebra finch. “And you’re always welcome to go work for Sommers and search for invisible memories with him.”

“They are not going to be invisible for long.”

“Forget engrams,” David said. “Single neurons will not reveal memory. The sum of any animal’s recall, including a person’s, will always be much greater than its parts. Memory has to be a system that grows from emergent properties.”

Anton didn’t say anything.

David continued. “You’d need to have a way to watch the nerves take on and then lose shapes with different behaviors. If you could do that in an animal with learned language, which you never will, you might get invited to the herring fest. Besides, there are more important questions to be answered, like how and why does a bird learn to sing in the first place?”

“Well,” Anton said. “I happen to like herring.” He looked over David’s head toward Rebecca and gave her a wink.

Rebecca smiled back.

“Are the thermistor probes ready?” David asked.

Anton handed him a probe, and then stepped in to train his eye into the second ocular. David worked quickly and expertly, adding commentary only occasionally. He excelled at this part, the artistry of measuring every aspect of a bird’s song. Anton had come to David’s lab because he was known internationally for his ability to make birds sing. They sang with weights on their backs and magnets stuck to their beaks, or with half their air sacs packed with sponge. Despite the nerves he cut, the red, blue and green wires he threaded across their skulls, just below their skin, or the electrodes inserted above their hearts, or on their rumps, they sang.

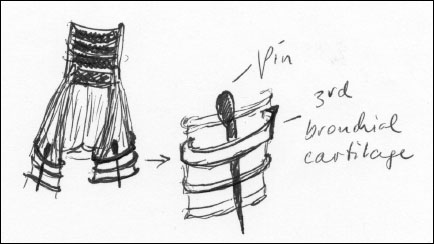

David spoke quietly as he inserted the tiny thermistors into the bird’s bronchi, thermistors that would measure airflow through the two halves of the syrinx, the bird’s version of a larynx.

“Herring,” David said. “You Europeans eat the strangest things. One time in Italy they gave me slivers of white pig fat and expected me to be happy.”

“Lardo?”

“Right, lard.”

“Not lard. Lardo. It is excellent,” Anton said. “Cured in marble caves in Tuscany.”

“This is the whole point I’m making, Anton. I’m trying to teach you good taste. If you want to be successful you’ve got to develop good taste in science. Not pickled herring or pig fat and definitely not engrams.”

“Lardo is considered a delicacy.”

“By whom? The Romans who ate themselves and their civilization to death?”

Like that of most Americans, David’s knowledge of history was mediocre, but Anton refrained from making any more comments.

“Pass me another probe,” David said.

Anton put it in his hand. David positioned the probe in place and began to sew up the bird.

“So is that what made you switch from mice to birds?” Anton asked. Like him, David had done his graduate work on mice.

“Is what made me switch?”

“Trying to find out how a bird learns to sing?”

“Well…yes, that and the fact that I took a bet.”

“A bet on what?”

“On whether birds would be as good as mice when it came to studying the brain.”

“Who did you bet?”

“A friend in graduate school.”

“And so, he lost?”

David stopped working on the bird and looked up.

“Indeed, he lost.”

“You don’t seem happy that you won.”

David was still for a moment, as if in a memory.

“Maybe we should make a bet,” Anton said. “I’ll take the risk and gamble. That’s exactly what I’m proposing to do with the engram experiments.”

David looked down at the bird again. “Damn it.” He pulled the bird from the anesthesia funnel. Anton stepped back. Rebecca rushed toward them. The bird lay limp on the table. David stood and the chair rolled out, hitting the laboratory bench behind him in a loud crash. He tapped his index finger in regular pulses on the limp bird’s breast, stopping for a second and then continuing the rhythmic tapping. His head an inch above the bird. “Breathe, Breathe.” Although it had been known to work, this bird didn’t respond to avian CPR. The three of them stood for a second looking down at the dead bird, until finally David, jaw muscles pulsing, turned and walked away.

Anton stared at the bird for a moment longer before he leaned over to flip off the flow of anesthesia, absentmindedly moving the funnel back into its place, scooting the bird to the right, collecting the surgical instruments in his hand. Rebecca didn’t move. A few moments later they heard the click of David walking back, his heels syncopating the tiah-tiah calls from the zebra finches.

“My fault. I’m sorry.”

“No one is at fault.”

“Another one on my conscience.”

Anton continued dusting up feathers. He raised his eyebrows slightly and tried to feign indifference. “It happens.”

“Yes, but we needed that bird. Now you have to start again.” Every death marked the premature end of an experiment, but some were particularly unfortunate, coming only days before the critical follow-up data had been collected.

Anton brushed the tiny feathers, which had stuck to his palms, into the trash can. “Before that, I would like another cup of coffee.” He reached out and squeezed David’s shoulder briefly on his way to grind the coffee beans.

David stood for another moment at the surgical table, unmoving, trance-like. Infuriating how quickly a zebra finch could go. One moment, the bird was under anesthesia, its heart beating slowly, the breaths regular, the surgery almost finished, and then suddenly, there were no breaths at all. “I don’t know what happened. I’ve done that surgery a thousand times. I had the anesthesia on low. It doesn’t make any sense.”

“Maybe the bird didn’t want to…” Rebecca said.

David waited for her to finish the sentence and when she didn’t, he asked, “Want to?”

“Maybe it didn’t want to be studied.”

A group of zebra finches erupted into a chorus.

“Of course it didn’t want to be studied, but that doesn’t explain why it died.”

“Maybe it chose to.”

“What?” David’s voice was curt.

“Chose to die.”

“Birds don’t choose to die. That makes no sense.” He took a deep breath and continued. “You’re anthropomorphizing, Rebecca. It’s a common mistake, projecting human emotions and agency onto animals.”

She shrugged her shoulders and continued cleaning the cages.

David stood still looking down at the bird. There was nothing natural in it, nothing of the struggle between predator and prey, no overt brutality or violence. And certainly no choice. Simply a heart going from slow to stop. The air sacs collapsing onto themselves; the neurons, already asleep, now fully arrested. He raised his voice. “How can you think there is choice in this? The bird didn’t choose to die any more than I chose to kill it.” This was a death for no purpose, and more than anything he couldn’t abide subjecting an animal to experimentation for no purpose.

“Do you want me to clean up?” Rebecca asked.

David nodded and walked away.

Rebecca rubbed the black surgical table with soap and then followed with alcohol. She picked up the zebra finch, and put him on a paper towel on the counter and went to find Anton in his office.

Anton was sitting at his desk, hands interlaced, head bowed, the small thinning spot on the top of his head exposed. He heard someone at his office door and looked up.

“Rebecca?” He emphasized the R.

“Sorry,” she said. “I didn’t mean to interrupt.”

“No problem,” he said.

“Were you praying?”

“Maybe. I do not know.” He forced a smile. A funny question. Most people assumed biologists weren’t religious. His eyes skirted to the window. “Thinking.”

The view from this office was not of the valley to the west and north, but of the snowy foothills behind the institute. At midday the white hillside reflected sunlight into the building. The Alps were never so bright in winter.

“I’m sorry.” She glanced out the window to where he was looking.

“Have you noticed?” Anton asked. “We can look out these windows, but no one can look in. From outside, the glass reflects sky, snow, trees.”

“Except at night,” she said. “At night, when the lights are on, these labs are like fish bowls.”

He looked back at her. “True. Except at night.”

“Was the bird really important?” she asked.

He shrugged. “Well, it’s not suffering anymore.” He was conscious of the fact that it wasn’t an honest response. Unlike David, the birds did not call to him in any special way. He cared about their well-being no more than he cared about the well-being of beef cattle, or chickens or pigs.

“Does it bother you, I mean, to work on them?”

He made eye contact with her, holding her gaze. “Of course.”

There was a flash from the diamond stud in her nose as she tilted her head. Her skin looked pale and perfect against her dyed hair. He wanted to say something to her about his frustration with the bird research, his search to find engrams, his quest—for lack of a better word—to discover how memories were made and where they were stored. Instead he gave another slight shrug of his shoulders. “Mice are worse.”

Rebecca placed the zebra finch in her palm, its head drooping between her thumb and forefinger. His body was still warm, a warmth that was expressly unsettling because she knew it was temporary. The hyperactive bird had been stilled and silenced. She held him closer and blew on the soft orange cheek feathers and then smoothed them down again with the tip of her finger. From a drawer she pulled out a plastic bag and shook it open. Why did she feel sad? Was she more sorry for Anton, who she could tell was upset, or for the bird? Was it so bad, the bird dying? Or was it her own discomfort with the conversation and David’s anger? She couldn’t say, but she knew that death could be a choice. Hadn’t she also made the choice to end a life? She slipped the limp bird inside the bag, labeled and stored it away in the freezer.

In the two years since college, Rebecca had been a lot of things: aspiring photographer, waitress, daycare substitute, merry maid, and then aspiring photographer once more before being hired as a technician in this laboratory. She didn’t count her other intervening occupation—girlfriend to the famous Chicago photographer. Didn’t count the months spent walking the windy streets of the city, confined by forbidding buildings and the glare of tempered glass. Didn’t count the blank moments she’d spent under his body or the time she’d been trapped in the deep red glow of the dark room.

A few weeks after she returned from Chicago, she’d found David’s lab as she was scrolling through websites related to vocal cords. Her voice had become breathy in Chicago and she wanted to know whether it would correct itself or whether she needed to see a doctor, but as usual, she’d gotten lost on the internet, her attention taken from link to link. A reference to vocal folds had brought her to videos of humans singing opera clips. Someone had stuck cameras down their throats recording grotesque and mesmerizing images of vibrating flesh. That website had taken her to another page that mentioned birdsong and she’d clicked from page to page watching birds sing in slow motion, their beaks moving exquisitely in a kind of ballet, creating songs more complicated than she’d ever thought possible from a bird. And then she’d landed on David’s page, which had, just as she’d seen for people, videos of the vibrating vocal folds of birds, and she realized that the lab was here in the city.

On the home page there were six birds on a background and as she scrolled over each bird, she heard its song, the melodies lovely and sweet. Could it be that she’d never truly listened to a bird sing? We study how and why birds sing. And below that: Our work bridges the neural control of a complex learned behavior to its evolutionary and ecological relevance in the natural environment. She didn’t really know what that statement meant. She clicked on David’s name and saw a round-faced man with dark curly bangs almost covering his eyes. Her first thought was that he needed a haircut and a better photographer. She discovered that he was teaching and on a whim, decided to go to the class. She sat in the back of a 250-person lecture room, and although she’d never been much interested in biology in high school, his animated lectures about birds drew her in. She returned for the next lecture and the next.

It took her a while to convince him to let her work in the lab, but he finally agreed. She was made to understand that punctuality was critical, and so she arrived at 8:30 sharp. He moved with ease within the regular spaces of the building. His clean-shaven face, quick boyish smile and equally boyish body had a disarming effect. The two of them spoke little but he was patient and kind and quick to laugh. Only now, as she’d just learned, he had a temper as well, a measured rage as he tapped his index finger in regular pulses on the limp bird’s breast, hissing a useless command to it to breathe. That outburst unsettled her, as did the conversation about choice afterwards. He seemed angry, and in her discomfort, she sought out Anton. She suspected Anton didn’t really want to research birds but the thought made no sense. If he didn’t want to research birds, then he wouldn’t be doing it, would he?

She looked around the lab. Black countertops, computers, wires, bottles of chemicals, cages stacked on top of cages. Theirs was the only laboratory at the institute that studied birds, the only one that smelled of dust and seed, the only one where feathers floated like snowflakes in a glass paperweight. The other neuroscientists studied mice which were kept in the basement. David had taken her down for a tour and she’d seen the rooms, each with hundreds of twelve by twelve-inch cages. Bred to express one gene or another, only their blood, cells and DNA mattered. Once the right strains were achieved, the mice were guillotined and frozen or ground in a blender. Liquid samples of blended skin or neat slices of brain could then be brought up to the laboratories for analysis. “Unlike our birds,” he said, “you don’t need to see or hear a mouse.”

She had loved what he’d said in a lecture. “Birds will tell us about the evolution of language. They might reveal the secrets of communication. Unlike you and me, a bird can be opened up. We can see what’s on the inside.” She liked that idea more in theory, as a metaphor, than she did now in practice.

She heard a white-crowned sparrow pecking inside his soundproof box, a repeated angry sounding tap. These are angry times, the photography professor had said with a shrug of his shoulders, excusing himself. Thinking of him brought on the usual frightening sense of defeat.

She made her way over to the birdcages, stepping around computers, microphones and amplifiers, mobile recording stations connected to one another by thick red, black and green wires. The stations were rolled about during the day, moved in front of one birdcage or another during experiments, rarely turned off or put away at night. She looked in at the Inca dove. He was the only one of his kind in the lab and she wondered whether he was lonely.

In the first days of the job, she had tripped again and again over the cables, and David, watching her untangling herself, had said nothing, only raised his eyebrows. Likely he had worried that, at best, her trips would unleash the machines, zero out the electrical signals, stop the collection of data. At worst, she might jerk the birds from their tethers, leave them hanging in midair, fluttering and panicked, undoing the hours of wiring surgery he’d done.

Forget it, she told herself when she returned from Chicago. Think of it as a bad picture, out of focus, poorly exposed, but she had not succeeded in destroying the memories. There were still frightful pushing, pulling dreams at night, followed by moments like now when she could hear him speaking and almost feel the heavy breath of his whisper in her ear. These are angry times. Days in which she worried a part of him had been left, forever imprinted on her body, that despite the cleaning out of her womb—the suction, scrape and bleeding that followed—he had not been totally removed.

She went down the hallway to the aviary, opened the door and stepped inside. She had no business in the aviary right now, nothing to do here, but she wanted to be alone. In this space, amidst one hundred flying, tooting zebra finches, she knew she wouldn’t be bothered because no one ever came in except her and the student who fed the birds on the weekends. She leaned against the wall while birds zipped around one another, the sounds of caged wings echoing off of the narrow, tiled walls.

Photographers should be seen and not heard. His eyes were dark green, waterless. He was a visiting professor, quite famous, who’d been brought to the university for a two-month course. He singled her out after he had seen her photograph and invited her to coffee.

It seems that you already understand that. A pause. Personality can only come through the photographs. He’d touched her arm gently. You don’t want people to notice you. It interferes with the work.

She smiled back, felt his leg muscle flex against her thigh under the table.

Quite remarkable to already know that at your age.

His fame excited her. His attention, in those months focused solely on her, meant she had true talent. He was her reason to leave, her gate to a real city, her introduction to working artists. By the time he left, she’d made plans to move to Chicago.

A zebra finch singing near her stopped suddenly. She watched him cock his head, approach his food container, and then eat a seed. Standing now in the aviary among the birds tooting and bleeping around her, she tried to quiet her mind and remind herself that she was as far away from Chicago and the photographer as she could get. The bird laboratory was a kind of refuge, a place where she was safely in the company of two scientists tapping away at computers, scribbling diagrams on white boards, fighting about whose hypothesis was right. Surrounded by birds. Beautiful, loud, trilling, squawking—but speechless—birds.

She took a deep breath and left the aviary. Back in the laboratory, she sat down at the main computer. Every day after the birds were fed and the cages cleaned, her job was to make three copies of all data recorded the previous day. She stored the cds in large, three-ring folders that were kept on bookshelves in the conference room. She inserted a blank disk, dragged the files and clicked on the green button. While the files were copying, she lifted her head and looked outside. The pink morning had turned blindingly bright, the sun reflecting off the frozen crust of a new snow.

She heard a zebra finch sing a series of songs and looked over at him. His backpack held wires that were woven up, through, and out the cage. Plugged into computers, they recorded his breaths, heart beats, and any songs he chose to sing. This one was a loud and prolific singer.

When the data were copied, she hit the eject button, removed the disk and used a fine black pen to write the bird’s number, the names of the files and the date. She inserted another, dragged, double clicked and stared at the lifeless screen while the computer worked. She heard Anton’s whistle and listened to him humming and moving around the lab behind her. She sat up straighter in her chair. He seemed to be in a better mood again.

There was something appealing about him, but she was struggling to put words on just exactly what it was. He seemed simultaneously accessible and inaccessible, strong and vulnerable, serious and light-hearted. The scar on his cheek had twitched as they’d spoken in his office. Was he winking at her again? Was that wishful thinking? She didn’t know him at all. They’d hardly exchanged more than a hundred words. She imagined his type was quite common in Italy, or wherever he was from, but she wasn’t accustomed to men like him. She didn’t trust her feelings.

Since starting to work in the lab, she had begun a new plan. She would save money so that she might travel and take pictures of birds. In her spare time, she read about them, their hollow bones, the air sacs pumping air through their lungs, their funny voice boxes imbedded in the middle of their chests, their ability to fly up and immediately away, migrating to a new place two times a year. She fed them, scrubbed their cages, scanned their nests for eggs. She did as she was told, positioned cages with female birds in front of those with males, tempted them to sing. She was a twenty-four-year-old woman at an interim job. Temporary and safe. And with Anton and his accent, the many species of birds, it almost felt exotic. She had no expectation that she would slip day by day, imperceptibly at first, and then obviously, into love with a man and the sound of his voice, or birds and the world of their bleating songs.

The week his bird died, Anton stayed late at work every night. On Friday he sat in his office, papers spread across the desk, staring down at printouts of songs. The building had mostly cleared out. Rebecca left at five and David had gone to dinner downtown.

Computers were powered down, doors pulled shut, the internal alarm system enabled. Even the post-docs were relaxing. In the bathrooms, women were hanging up their lab coats, pulling on winter boots and lining their lips with shades of red. Soon, like David, they would be stepping into restaurants humming with conversation, sitting down at tables, poring over menus, ordering lamb, pork or steak, clinking glasses of beer or wine. Anton liked to be alone in the lab at night with only the birds, quiet in their cages, and the hums and purrs of computers and machinery.

He was glad to have the space to himself, never inclined to join them because he usually ended up feeling confused like an old man who was hard of hearing. Crowds and background noise made understanding English, not to mention being understood by others, more difficult. Instead, he often worked late, returning to the laboratory after dinner, walking from his apartment up and across the empty campus in the dark. He would swipe his card through the security system, wait for the green light to flash, and enter the institute.

He took out a piece of paper and began to write an over-due letter to his mother. He could see the blue envelope of her last letter on the table at his house, where it had been for weeks, and tonight he finally felt like he could cross the distance and write. She wanted to know what this western American city looked like. He could have just taken a picture and sent it to her but he’d always refused to buy a camera. Instead, he wrote:

The city is constructed of boxes. The institute that houses our laboratory is a transparent, well-guarded rectangle. Inside this rectangle there are smaller spaces, mostly squares. The outer walls of the building are constructed of red brick and glass, the inner walls of the same. Rooms are delineated by plasterboard, doors and glass. Half-walled small spaces define work cubicles for students. My office is a perfect square. In the conference room, the walls are cut into parallel lines by the bookshelves and each book a small rectangle of its own. Down the hall, the aviary is a dirty, noisy square. The experimentation room, lined with thick, white Styrofoam, where I spend most of my time, is soundproof. Outside the walls, the desert is grey and flat and leads to another mountain range. I do not know what’s on the other side.

The problems with his research worried him. He didn’t know what it meant but lately there had been a lot of dead birds and the death of the bird this week was a major set-back. He took down the blue binder and flipped through the pages until he found the one for “Red 31.” In her neat handwriting, Rebecca had printed the date and next to that the word deceased. He studied the bird’s history looking for clues as to why it suddenly had died, and without finding any, he closed the binder. He wrote:

I’m not as sure as David, who came to neuroscience through a love of birds and their songs, that we are uncovering the truth of birdsong, and at times I doubt that it can even be done. Unlike him, I just want to understand circuitry, the wiring of memory. Truth is, I don’t care much for research with birds.

It was funny how the act of writing made feelings more concrete and the act of writing his mother, in particular, with whom he’d shared more words on paper than in person, brought out his loneliest self.

Birds. Anton didn’t like them much. Plain and simple, though they’d been a constant presence in his life. His grandfather’s nightingales. The storks he worked on for his master’s thesis. And now this work. He avoided looking at their eyes and at the sloughing epidermis where their beaks met their faces. He didn’t like the scaly feeling of their spindly legs or the way their toes sometimes curled around his pinky finger when he held them. He didn’t like the feeling of their quickly beating hearts or warm bodies in his hand, and the truth was, he resented them deeply when they died.

All I want to do is use the bird to understand how memory works. Measure it. Distill it. How does our brain memorize patterns of sounds? If we can memorize, does that also explain how we can forget? Is forgetting the opposite of learning?

The talking part, at least, was relatively easy for him. There were other, larger, problems. Computers crashed. Expertly placed electrodes failed to record a pulse. Some days his hands shook and he couldn’t be trusted to open a bird, or like this week, the bird died for no apparent reason.

Rebecca had suggested that the bird had died by choice.

“Surely, it’s an absurd notion,” David said to him later, “but I don’t have a better reason for that bird’s death.”

Choice. An interesting concept. He continued writing.

Everyone knows that birds don’t migrate east and west. South American species come north. European birds fly south. I feel I’ve been blown off course, like one of those confused “accidentals,” mistakes that bring delight to the bird fanatics who spot them. Just like those birds, I fear I’m destined to die of starvation, disorientation, or both.

What would his mother make of this letter? They’d never talked much when he was a boy, but since coming to the States, their letters, for Anton at least, seemed to function as a type of journal. They never responded directly to what each other had written, though they continued writing back and forth in an old-fashioned way with pen and paper and stamps.

He heard a soft whistle coming from a tiny microphone in one of the white-crowned sparrow coolers. Enclosed as they were, they didn’t know day from night. He listened for more. There was a buzz and trill, a tremolo of sorts, and then the descending sweep. No outside stimulus seemed to be needed. As it was, in its solid enclosure, this bird could only be singing to itself.

Anton had been in the States for almost five years and he was ready to go home. He’d come at the urging of a professor, and then finally, his mother.

“One of your professors stopped by today.” She was at the table sorting through photos while he arranged cold cuts and cheese on a plate.

“Which one?”

“Gianetti. He said he admired my work.” There was a slight smile on her face.

Everyone admired his mother’s photographs and he wondered what else Gianetti admired about her.

“He said that the USA is the only place to do neuroscience.”

Anton cut a slice of cheese.

“He said that here his technicians spend their days washing pipette tubes, but in the USA they use them and throw them away like bottle tops. A garbage can-full a day. He said his lab needs another fifteen years just to catch up to what they’re doing over there.”

Anton placed the plate on the table beside her, careful to not get the food too close to her photographs. Their lab was not fifteen years behind and he doubted Gianetti, with his quiet but constant ego, would have ever admitted such a thing even if it were true.

“He said you’re too talented to stay here. He needs you over there.”

The first post-doc, four years in St. Louis, got him a couple of scientific publications and landed him this second post-doc with David; but now he needed results worthy of publication in Science or Nature. Dead zebra finches were not a ticket home. He heard David say, This is how science is done. Baby steps that add up over the years. Anton didn’t have time for baby steps. He needed the elusive engram that David didn’t believe in.

The world of neuroscience had grown quickly. When David was a post-doc, there had been about six thousand neuroscientists, but by the time Anton went to his first meeting, attendance had doubled, and now they were predicting that there would soon be twenty thousand neuroscientists worldwide. Whereas David was on the forefront of the first wave, Anton was a late arrival. If he had any hope of a career in neuroscience, he needed to sprint. He needed a big win, a World Cup goal.

The white-crowned sparrow sang again, and Anton half-heartedly sketched how the song would look if digitized. Whistle, buzz, buzz, trill, trill, downward sweep.

Tremolo always preceded by a trill. Auditory awareness of one thing seemed to bring on the other. Was that fixed in the brain?

Everyone knew that auditory feedback was important. The definitive experiments had been done long ago. Take out a bird’s ears and not only does he go deaf, but slowly he loses his ability to sing. What if he could turn that tidbit of information about deafness into a tool to find engrams? What if Anton could take away the bird’s ability to sing, but not the ability to hear? What would happen if the bird sang but made no sound? He ought to, if predictions held, forget how to sing. Could he then see changes in the bird’s nerve cells as it began to forget its songs?

He reached for a piece of paper and began sketching the syrinx, the bird’s voice box, imagining how it might be possible to temporarily keep it from vibrating, devising how he might be able to mute a bird.

He labeled the parts. A syrinx was an awfully small place to work, no bigger than a rice grain. How would he keep the bird from making sounds?

He heard rattling at the window and looked outside. A storm was moving across the valley. Frozen rain pelted the windows and the glass blurred. He’d arrived in the city on a night much like this one, cold and black, huge snowflakes coating the road. David had picked him up at the airport and given him a quick tour of the downtown, bright and shiny in the nighttime snow, the Temple Square, still lit in red, blue, gold and green, though Christmas had already passed.

He looked back at the drawing of the bird’s syrinx again, and suddenly he saw it. If he could keep the labia from moving, then theoretically there should be no sound. He thought he knew how he might do just that. He jumped from his chair and went to fetch a zebra finch. Even though the finch’s song was less interesting than the white-crown’s song, he wouldn’t try to mute a white-crowned sparrow. Those birds were reserved for David’s syntax experiment.

He slid the finch into the plastic funnel and waited for the anesthesia to work. When the bird was asleep he sterilized the tools. He cut tiny pins from pieces of metal, flipped on the microscope’s light and lined up everything on the table.

A few weeks after he’d arrived in Utah, he met Francesco, who owned the Italian deli downtown. Francesco leaned over the counter and spoke in Italian as if he were revealing a secret. “The church cranks out married couples every Sunday like ravioli from a pasta maker. The pope is supremely jealous. The Vatican only dreams of practitioners like these—no sex, no wine, no coffee…”.

“No coffee?”

“And ten percent of your paycheck, too.”

The religion didn’t bother Anton. What did affect him was the openness of the desert, the space and barrenness of the West. If he kept his vision on the mountains he felt at ease, but looking across the flat, gray valley or driving into the desert was disorienting. Just west of the city the salty lake hovered like a mirage just inches above the horizon. If you were at its shore on a sunny day, the white salt reflecting sunlight could blind you.

Space seemed to be one of the main things that made Americans different from Europeans. Anton had come to believe that fundamentally, the American experience was based on just that: dealing with loneliness in vast areas of land. Where Europeans had high density, medieval cities and two thousand years of ruins to temper their loneliness, Americans, especially those in the West, had horizon, massive rocks, thorny bushes, and a few ugly cities that looked like they’d been constructed overnight.

“Don’t you feel lonely out here?” he asked David once.

“Often,” David said, “but I love space. It’s liberating to be on a frontier where no one can tell me what to do.”

David didn’t mind telling others what they could and couldn’t do though. He’d forbidden Anton to work on engrams. Not my lab, not my funding, not my birds.

The zebra finch lay on the table before him, breast exposed, slow pulses up and down, breaths in and out. He had made a small opening in the bird, pinned the skin back and now he was looking down at the syrinx, a forked section of cartilaginous rings, the valves inside no bigger than rice grains. He meant to weave the tiny pins in one side of this ring and out the other. Picking up a pin with the forceps, he steadied his elbow on the table, moved in closer and held his breath.

“What’s it like?” his friends at home asked.

“Like a giant Ferris wheel.”

They presumed he was making a joke, laughed, lifted their glasses and sipped their wine, but he’d been serious. Coming to the States for the first post-doc was like stepping into the small cabin and hearing the door click shut. He remembered the beginning weeks of panic, disorientation, loneliness. Forget the fact that he could read and write in English, he could only make out half of what they were saying. Everything in the American accent sounded garbled and mispronounced. Language, he learned quickly, was a clear line, and you either stood on one side or the other. Making out the words was not enough. You either understood what a person was saying, or you did not.

The big wheel had begun to turn and then he’d experienced something new, the freedom of leaving Südtirol, his life there, his old self, behind. On the way up there was one new perspective after another, the horizon always larger, his vista longer. There was a brief time when the wheel stopped at the top, and he’d been perched there, feeling the gentle swing of the cage, enjoying it all, but then the wheel had begun to turn again. Heading to the bottom once more, he wasn’t so enamored. He felt caged, saw the bars more than the horizon.

He looked down at the bird. It appeared as though he’d succeeded in placing a pin through each labium of the syrinx but he wouldn’t know until the bird tried to sing. He tied off the last stitch and doused the suture with a bit of surgical glue. While he waited for the bird to wake up, he cleaned the table and tidied up the instruments. He wouldn’t say anything to David. If it worked, he would have to see that this was the definitive test. The engram would appear.

By the time he trudged down the hill from the laboratory, head bent against the wet snow, orange scarf wound around his chin, eyes squinting into the shimmer and dim glare of streetlights, he was feeling almost giddy. He looked into the sky, felt the snow hitting his cheeks and blinked the drops away from his eyes. In a few more hours everything would freeze once more, the slush turning to ice in the early hours of the morning. Tomorrow he’d be slipping and sliding as he walked up the hill toward the institute.

When he opened the screen door to his house, a small box wrapped in brown paper tumbled out. He bent to pick it up and squinted in the dim light to make out the return address. It was from his mother. At least, she was in Südtirol. For months he’d been following the Italian newspapers and the stories of the unrest in Somalia, the battle of Mogadishu, looking as always, for her photo credits. Feigning ignorance on this side of the world, he’d written. Can you give me an update? Over here, the news is fifty percent weather report. She’d understood what he really wanted to know and said she wasn’t on this assignment, but Anton hadn’t known whether to believe her or not. Lately, as if trying to make up for his childhood years, she seemed to have become protective of him.