The lights inside the laboratory made it brighter than the overcast day outside. Zebra finches tooted at one another, scattered seeds, flitted up and down. A male, wired for research, hopped along the perch in his cage and cocked his head. He twisted around, faced backwards and then twisted back again. Ample food, water, predictable temperatures. Regular daylight. Regular darkness. The hum of computers, keyboards and human talk, all familiar sounds to generations of birds accustomed to life in the laboratory.

Outside, a flock of waxwings landed in a serviceberry tree, their plump bodies and crested heads scattered among the branches. A male called out a high zeee whistle. A female tipped her head, answered the call with her own, and flew up. With a red berry in his beak, the male hopped toward her, turned his head to the left and presented her with the berry. She leaned in and took it into her beak and then hopped away. At the end of the branch she turned and hopped back with the berry once more. The male inched closer, accepted the berry when she offered it, mimicked her dance to the opposite end of the branch and returned. Around them, the other waxwings made hissy, high-pitched whistles. The sun was low in the sky. The valley stretched beyond them. The two birds passed the berry back and forth a few more times, and then, quite suddenly, the male swallowed the berry and the entire flock took flight into the gray afternoon light.

Zugunruhe. From German. Zug meant movement or migration; Unruhe was for anxiety, restlessness. Zugunruhe was everything a bird did before migration. After the fat had been added to muscle, the restlessness began. It was the energy before flight, the anticipation of mating season. It was what made the robins crazy to sing. And then months later, when the days got shorter and the singing stopped, when the babies had—alive or dead—left the nest, zugunruhe described a bird’s behavior before it flew back to its wintering ground. It was an orientation towards a home, either north or south. It was a frenetic jumping, hopping, a mad fluttering of wings, birds in love with life.

Anton and Rebecca spent the next seventy-two hours together, walking to the laboratory after coffee, cleaning cages, setting up experiments, checking on “Blue 27.” Late at night, they raced, hungry and elated, down the hill to Anton’s house. He cooked dinner. They ate and drank with the eagerness of children and then afterwards, he put on traditional Südtirolean music and taught her to dance. She loosened her hair, laughed and mimicked his moves.

He told her about the book his mother had sent him. “The birds must pass through seven valleys before they get to their god. And one is the valley of love.”

“There’s a valley of love?” Rebecca leaned over his shoulder. Lemon. Always the scent of lemon. She nuzzled against his neck but she was too close to his ear and he couldn’t decipher her muffled words, only felt her gently bite down on his ear lobe. She leaned in and kissed him, holding her lips to his for a long moment and then they moved a few inches apart. She ran her hand over the scar on his cheek.

“What’s this from?”

“Guitar.”

“How?”

“I was sixteen, tightening a guitar string. It snapped and hit my face just here.” He didn’t tell her that his mother hadn’t even noticed. “Now I have sound vibration forever imprinted on my skin.”

“It’s not very obvious.”

He pulled her close. “I like to think it’s like the dots and dashes of Morse code, comprehensible only to those who bother to learn the code.”

They stared into one another’s eyes in the evening light, not speaking, just touching. There was a freedom in their togetherness, a mutual relaxation, an implicit understanding that neither had experienced before, as if they were a set of mirrors, seeing themselves anew, seeing how the other could see. They did not begin, as some lovers do, to tell each other of their pasts. Setting their conversations only in the hungry immediacy of the present, the past was left to involuntary recall.

When Anton turned eighteen, his father took him out for a night on the town. He would have avoided the evening if he’d been given some warning, but there was no one to warn him. His mother was in Africa, absent as she was so often during those years and his grandmother was surely oblivious to the plan. They were to go to dinner, which they did, and to a movie, which they did not. Instead of a film, he took Anton to a hotel outside the city, where he ordered more drinks, and as it turned out, women.

The women were in their thirties. Forward. Uninhibited. One woman sat on Anton’s father’s lap at the bar, her skirt high up on her leg, her lips red, as if she were acting a clichéd part in a movie. Anton disliked her immediately. He’d never seen his father with a woman and couldn’t imagine him liking a person so different from his mother, who was reserved, sophisticated, smart. The other woman drank, smiled, and laughed at whatever Anton’s father said. Anton didn’t speak.

Anton remembered protesting when his father told him they’d be staying the night. Pushing him into a room, he said, “What’s wrong? You a fag?” Anton remembered the woman, who both scared and excited him. Breasts. Wetness. The scent of fusty, overly-perfumed sweat. It was all over quickly. Afterward, she laughed and caressed his face as if he were a child. He slapped her hand away. She continued laughing and left the room. There was knocking on his father’s door. Anton got up, showered and then got back into bed, lying awake long into the night, overwhelmed by a rage that surfaced toward his mother. And then he fell asleep.

The next morning, the women were gone. He and his father breakfasted in the hotel restaurant, coffee and toast, read the newspaper and then drove back home in silence. The mutual, but awful, experience was concluded by a hard thud delivered by his father onto his back as they entered into the house. Anton could not say now what she had looked like. Whether she’d been tall or short, blond or dark. Until Rebecca, he had associated sex with that night, sex with shame and anger. The memories, fragmented by wine, whiskey and a will to forget, could still make him shudder.

Anton woke from a dream and found Rebecca beside him, her fingers lightly touching his arm. “I fell asleep,” he said.

“I was dreaming.”

“Was it bad?”

“Yes. How did you know?”

“You twitched. Your face was sad. What was it?”

“I think it came from the book I’ve been reading. In the dream, I was in the book, going through the valleys with the birds, but I got stuck in one place. It’s hard to explain now, but it was really frightening. There were parrots but they didn’t act like parrots; they buzzed around like flies and I kept having to duck out of the way so that they couldn’t bombard me.”

“Like Hitchcock’s movie?”

“Sort of, but the parrots were yelling. They told me that I would never be able to leave, that I would suffer, that I would have misfortunes, that I would fail.”

“You’re not going to fail. Besides, that’s why we say ‘it was just a dream,’ right?”

“Indeed,” he said. “Just dreams.” Strife and grief. What was the dream trying to tell him? That he had to stay in the United States? He couldn’t give up on the muting. That he didn’t really have a choice? He pulled her close. “Please stay with me tonight.”

She inched closer to him. “I’m going to stay with you every night.”

Rebecca spent the week at Anton’s apartment, but he didn’t want David to know.

“I think he is alone.” They were eating cheese and olives at the kitchen table. “Only the laboratory and birds, nobody at home. Someone told me that his wife moved out.” Anton leaned over and kissed her. “I am afraid David will be jealous.”

She laughed. “Anton, he doesn’t even look at me.”

“I am Italian and male. I know things you cannot.”

“I thought you were Südtirolean.”

“In this, we are all the same.” He held an olive up to her lips and she took it into her mouth. “Women, I think, understand very little about men. Like boys, we do not know how to handle feelings. Jealousy is a dominant gene. The weaker the man, the more he needs power. Our parents learned this during WWII: Hitler, Stalin, Mussolini.”

“Hard for me to see how Mussolini applies. We’re talking about a bird laboratory and a boss who doesn’t much notice me, not international history.”

“Very relevant.” He popped an olive into his mouth, talking around the pit. “Question of scale.”

“Scale?”

“In Tuscany, there is a village called San Gimignano up on a hill and surrounded by a stone wall. When you go there, you see towers.” He spit the seed into his fist. “There are maybe twenty towers today, but one time this village had one hundred towers. Each family showed their riches by building towers taller than their neighbors, and sometimes they had fights tower to tower. Everybody who goes to this village today laughs at those people, their small view and all that money put into building pointless towers, but I think nothing has changed.” He took a sip of wine. “Every man likes a tower.”

She rolled her eyes. Anton went into the living room, came back and handed her a book. She looked at the title. Theory of Sexual Selection. “What’s this?”

“Everything you need to know about men, and it will tell you why male California quail have the curled feathers on their foreheads, which you like.”

“Great. A guide book to birds and men.”

Anton left her at the table with the book while he began chopping an onion for dinner. “It’s what I’m telling you about San Gimignano. A biological explanation for men and towers. Why we should not say anything to David.”

She opened the book and glanced at the pictures of birds.

“Besides,” Anton continued, “American men are even more childlike than Europeans.”

“How so?”

“They play games. In the laboratory where I did my first post-doc they had this small basketball hoop stuck to the door. The students and the professor had competitions every day tossing a ball into the basket. They hooted and clapped and slapped each other.”

“Did you play?”

“In the beginning, yes. Later, I made excuses.” American men didn’t know how to sit and talk, share a story, a cup of olives and a beer. They passed one another quietly in the hallways, only coming verbally alive with their hoots during games, needing these physical activities to break tension, bond and reestablish dominance. He had always secretly chided them for their adolescent manners, but lately, he’d begun to think there might be advantages to their stunted maturity. A certain freedom. He’d written to his mother:

I like the Americans. They’re curiously free, almost childlike, not hemmed in by a sense of cultural history or historical responsibility. I wouldn’t want to live here forever, but there is a certain creativity that can come with this naiveté, this release from history. The food, by the way, is only good when I cook.

“Don’t you ever have the urge to let them go?” Rebecca asked.

Anton had lost himself in the memory of the letter to his mother. “Who? The Americans?”

She laughed. “No. The birds: zebra finches, sparrows, canaries, let them go.”

There was a sudden sting in his eyes so he stopped mincing the pungent onions and turned toward her. “Of course not. These are domesticated birds. They haven’t been free for generations. They would fly straight for the windows and break their necks.”

“Right, but maybe they shouldn’t be subjected to experiments and small cages.”

He turned back to the stove. “A cage is a cage.” He scraped the onions from the cutting board into the oil. There was a loud sputtering and then a low sizzle.

“What does that mean?”

“To some extent, aren’t we all in a cage?”

“I’m not talking metaphorically,” she said.

“Relative to what?” she asked.

“You’re questioning whether we have the…right?”

“Yes, I guess I am.”

He was silent for a moment. It seemed impossible to say it well in English, but really, it was simple. “Humans are a species, one of millions on the earth. We just happen to have unique technological and intellectual abilities. Big brains, opposable thumbs, curiosity and consciousness. We have the right to appropriate these abilities and skills just as any other animal does, just as any other animal would be expected to do.”

She took a sip of wine and was quiet for a few moments. “I don’t think that’s right.”

“What is right?” He added garlic to the pan, stirred and waited for her to answer, and when she didn’t, he turned down the stove, went over to her, lifted her chin and kissed her. “This is right, no?”

She smiled. He went back and added chopped tomatoes and basil to the sauce. A few moments later she asked.

“Do you think they’re saying anything to each other?”

“The birds?”

“Yes.”

“What do you mean saying something? Like humans? Talking?”

She nodded.

“No, I don’t think so. But you know, everyone wants to think they do. Aesopus, Democritus, Anaximander and Tiresias were all supposed to have understood the singing of birds. Francis of Assisi quieted loud birds. In the Talmud, Solomon is wise because God lets him understand bird language. There is the same idea in folk stories, the hero is given a gift so that he can understand birds, and the birds, like magic, save him from danger or lead him to treasure.” He poured the pasta into the boiling water. “There is something sacred about language, I think. We need to communicate. People hope that birds, because they sing and fly up to the heavens, will bring us closer to god. And god will help us understand.”

She cocked her head as she thought. “I don’t know. I think there is something more to them.”

“You’re not alone. In Sufism, the language of birds is magical.” He went to the living room, came back with the book his mother had sent and flipped through the first pages. “First the birds decide they need a king, but they don’t know how to find one. The hoopoe bird…”

“Hoopoe? Seriously, that’s the name of a bird?”

“Yes, a funny bird. Later I’ll show you a picture. You find it in Africa, and in summer, in Europe. This hoopoe wants to be leader, and he tells the birds that they must go on a long trip to get to their god. The birds agree that the hoopoe should be the leader, but then they all get scared and say they cannot go on the trip. The finch is frightened. The heron loves the sea. The nightingale can’t leave his love. On and on. The hoopoe says no, no, they must go. It’s funny. He tells the duck: Your life is passed/In vague, aquatic dreams which cannot last. Finally, after all the bird species have complained and the hoopoe has told them they must go, they agree to the trip.”

The poem could just as well be talking about doing science as finding the way to god.

How featureless the view before their eyes,

An emptiness where they could recognize

No makers of good or ill—a silence where

The soul knew neither hope nor blank despair.

As he read to Rebecca, Anton thought about the fact that he had no idea whether the zebra finches would tell him anything about memory. He had no assurance that the muting would be the tool he needed to demonstrate that engrams existed. He just hoped that it would be. He saw nothing of the emptiness ahead. Nor how that emptiness would obscure his ability to recognize the makers of good or ill in his life.

Rebecca crouched down and peered into the bird’s cage. She’d been checking on “Blue 27” every few hours for a couple of days and each time he seemed increasingly pathetic. He acknowledged her presence by hopping left and right and then sometimes by opening his beak to try to sing. Was he protesting what had been done to him? Or singing to her? What was he saying?

“Anthropomorphizing,” is what Anton and David called it but she didn’t care what they said. She knew the bird wasn’t human but that didn’t change anything. He was trying to communicate and she was trying to listen. It was much the same between people. Anton was trying to communicate and she was trying to listen, and in turn, he was listening to her and she was regaining her courage to speak. She wasn’t sure what to do with all these thoughts because on the one hand, she was thrilled. They’d done it together, and in the doing they’d become a team, spending every hour of every day together, and when she was with him she felt new and confident, the Chicago photographer far away. On the other hand, what they’d done together was in front of her with a backpack wired up and out the top of a cage, hopping and turning around on himself, perhaps struggling as much as she to understand. What they’d done together had made a bird mute.

Chicago. Sometimes she wondered whether she might have grown to like the city. She might have learned to withstand the biting wind that blew off the lake in winter, picking at her face and freezing her nose. Or the wet that chilled her even in bed. She would have accustomed herself to the skyscrapers, reticent soldiers along the lake, if it weren’t for that one night.

She had grown up with persistent feelings of constraint, spending her teenage years arguing loudly with her parents about vegetarianism, politics and the proper vocation for herself while making quiet plans to escape. During the summer, when the population in town tripled, she worked as a waitress. She listened to the tourists, the cadence of their German, French, Spanish, Japanese and other languages she couldn’t identify, and wondered what they were saying. She noticed how slowly they ate, how much they conversed, the way the women seemed to inhabit as much space as the men. She saved her money, and to her parents’ dismay and parting words of discouragement, she left to study photography at the university in the capitol city. Before long, though, she discovered that the city was really only a large town, and the art department had just two photography professors who happened to detest one another. Until the Chicago photographer arrived as visiting professor, she’d felt isolated.

He was famous, had showings in San Francisco, Chicago, Europe. He commented on her work and encouraged her in a way that no one ever had. She listened carefully and then spent days trying to do what he’d suggested before running back to ask for a new opinion. Her world opened into something different. She expanded in his presence to fit her own, secret belief in herself. Around him she believed she could be out in the world and become a photographer and she might take pictures that mattered. Two weeks after he left, she agreed to follow him to Chicago.

When she first arrived in the city, they spent days touring the Art Institute where he gave her tutorials in room after room. He saw the paintings in a way that was entirely foreign to her, stepping in close, peering at the work and then talking as if he was talking not only to her but to the artist as well. She pointed to one painting after another, and for each one, he told her about the painter, the technique, the reason it was special. He would slip his hand from the nape of her neck to her back and whisper lovingly in her ear. And then in the next moment, he’d turn to look at another piece of work, gone into a world of understanding that she hoped, with his influence, she might gain access to.

In those first weeks, they zipped around town in taxis from one reception to another, arriving late when the rooms were already full of happy, brilliant people. Artists and intellectuals. Gray-haired men with green eyeglasses, young students with ripped jeans and tattoos. He introduced her as his “muse,” which at first, flattered her but as the weeks went on, she noticed that people glazed over at her name, nodded their heads, but didn’t make eye contact. One night, she corrected him. “Not muse, nor concubine.”

She moved away from his side and situated herself within the younger group. She engaged a painter whose freckles matched her own. The photographer noticed her absence and raised his eyebrows to her from across the room. On the way home in the taxi, he laughed. “Concubine.”

The next night he went out without her, suggesting she take the time to use the dark room at the house to work on her pictures. What she didn’t know at first, was that he’d locked the door, but later when she’d tried to leave and realized she couldn’t, she became flush with anger and fear. Her only response, she realized, was to focus on her work. He would return, she told herself, and then she would get out and then they would talk. She focused on her negatives and their development, but then he came home drunk, not stumbling, but changed, vibrating, buzzing. He swung open the door of the dark room and flipped on the light switch. “How’s my concubine?”

There was a voracity about him as though he were expanding like bees spreading out from a hive and she instinctually backed away. He came toward her and reached for her face, taking her chin in his hand and raising it. “You’re so pretty.” He smelled of whisky.

She swatted his hand away. “You just ruined my pictures!”

He bent to kiss her and she tried to turn her head but he forced his lips to hers and pushed her mouth open, his fingers pulling hard against the corner of her mouth. He rubbed his unshaven chin against her chin. She pushed at his chest, tasting blood at the corner of her mouth. He stopped for a moment.

“What are you doing?” she said.

“I want you.”

His breath was bitter. She tried to get away, but he kept her against the countertop.

“Please,” she said. “You’re drunk.”

“I want you.”

“Okay, not here. Let’s go to the bed.” She thought in appeasing him she was making a choice but the bed didn’t soften his touch. She tried to call out but his hands clasped around her neck. She gasped. Her tongue flapped around inside her mouth. He clamped down on her throat, and then she didn’t think anymore. Denied air, choking on her tongue, she struggled to breathe. Finally, with a long low grunt, he stopped, and collapsed next to her, panting.

She took a series of shallow breaths. Too afraid to move, she lay motionless until she heard the congested breaths of his sleep. When she stood her legs shook and so she steadied herself against the wall. Liquid ran down her leg. She was raw inside and out. She wanted to scream, to muster tears and cry, but she couldn’t make a sound. She crept out of the bedroom, wrapped herself in a velour shawl on the couch and slept. When she woke a few hours later, she dressed and went out into the summer morning, walking for hours downtown. At midday she sat on a bench in Millennium Park and cried. How could this have happened? He had been charming and attentive and caring. She had never considered the possibility of him being cruel as well.

A male bird presented with a female, sings automatically, a hard-wired response, biology-speak for how the genetic code can govern behavior. In the experimentation room, Anton hooked up “Blue 93” by plugging wires from his transducer into a battery and a voltage meter and then he checked to see that the bird’s respiration was being recorded. He hoped “Blue 93” was a good singer. If he were, he would record his song now, mute him next week, and if he was lucky, the data would come fast. The muting was going extremely well. One more bird and he would be able to share it with David and then David would have to see how muting and auditory feedback could be used to find engrams.

He hummed as he turned on the microphone and recorder, and then whistled into the microphone to test that everything was connected properly. Satisfied, he went to collect a female zebra finch. When he slipped her into the box, she perched next to the male and gave him a peck on the head. The male made a single mee-mee call, hopped right and left. Anton stood back. Short calls were useless. He needed long songs. The female bird hopped to the male’s side again. He ruffled his feathers preparing for the dance that zebra finches often did right before they sang. The female ignored him and hopped away. The male responded to her withdrawal, as if automatically, with a long song bout, singing the same motifs over and over, his wings fluttering as he danced left and right. Yes! This one was a ready singer. The horizon might include the Alps after all. Switzerland, Austria, France or Italy. He had his preference, but he wasn’t going to be picky.

David returned from the symposium in Miami excited not about the prototypes for cochlear implants, but because a research group had revealed their findings on the FoxP2 gene. Known to be important, in some still undetermined way for human speech, FoxP2 had just been found in birds. Sitting in the auditorium at the conference, he’d experienced the tingling in his fingers and arms, an excitement he’d often felt as a graduate student and a post-doc, but one that had been absent for the past year, especially since Sarah had left. He in no way thought FoxP2 was “the” grammar gene in humans as the newspapers had reported it, distorting and exaggerating findings as they usually did, but its having been found in birds meant that the world of song and genetics was opening up. There was a new frontier to be explored. The “Decade of the Brain,” he realized, could be followed by one specifically for language. Soon, he thought, they might begin to understand the evolution of communication itself.

He heard Rebecca out in the main laboratory busy with the morning routine. His first inclination was to get up and say hello, but they were always a bit awkward around one another when they were alone. He would wait until Anton arrived.

While he’d been gone, the laboratory had been organized and cleaned as if they were preparing for an inspection. Research equipment had been put away in neatly labeled drawers, the black counters had been wiped clean, and the seeds swept up from the floor. The birds had never been cared for so well, the cages cleaned and lined with newspaper folded neatly into perfect squares at the bottom of the trays. The birds looked fit, their feathers healthy, colors lustrous, and they sang. He would make a point to tell her this.

An hour later, hearing Anton’s whistling, David came out of his office. “Do I hear that it’s coffee time?”

“Yes, sir. How was Miami?” Anton took down two mugs.

“Tropical breezes, girls in bikinis, mangos on the beach.”

“Like I thought,” Anton said, “you never left the hotel.”

David laughed. As it turned out, he hadn’t needed to leave the hotel. “What about here? You’re looking particularly happy and healthy.”

“Healthy?”

David stepped back and looked Anton up and down. “Yes. There’s a sort of glow to you. Anything new?”

Anton shrugged his shoulders and poured the coffee. “Just—what do you always say—baby steps that add up over years.”

David laughed again. Anton had taken on some of his expressions and they sounded amusing in his accented English. He told Anton about the newest results in deafness, implants and the genetics of birdsong, hoping that the FoxP2 might distract Anton from his interest in engrams and memory.

“I thought you weren’t interested in human applications,” Anton said.

It was true. FoxP2 and cochlear implants weren’t the only reasons for David’s enthusiasm. At the conference, he’d watched a woman interpreting for the deaf. Of course, this was nothing new; there were always interpreters at these conferences. He even knew a bit of Sign Language because he’d studied it at Sarah’s urging.

Sign language appeals to me, she’d said. It flips our assumptions, puts more effort on the person watching, or listening, than the speaker.

But there’s a reason no one chooses that form of communication, he’d told her, unless they’re forced to. It’s unnatural for us given we can speak and hear.

Come on, it can be our private language.

They’d gone to enough classes to pick up the basics, and he understood more than he could sign, but in the end he wasn’t motivated. Harder than learning a foreign spoken language, he knew there was no way he’d ever become fluent. Besides, they weren’t children and they didn’t need a secret language.

The young interpreter had coal black hair pulled into a short ponytail and was dressed in a white blouse, a beige knee-length skirt, no socks and red tennis shoes. Besides her odd tennis player outfit, what drew his attention was the way she used her body to sign. Her hands moved, of course, and often her lips. That was normal but she also used her cheeks, eyes and eyebrows too. His attention repeatedly slid away from the projector screen toward her in the shadows on the side of the stage. He listened to the speaker but watched her. She swayed left or right with the words. A zebra finch song became a jutting out of elbows. A canary’s long trill was a hand to her ear and then a fluttering of the eyes. When she meant to emphasize a point, she lightly stamped her foot. Her rising eyebrows alerted the listener to the main points, the summary statements, what the speaker believed were his most interesting results. She gave motion to the speaker’s intentions.

Afterwards, when he caught up with her outside the conference hall, her shirt was damp, beads of perspiration speckled her hairline as if she’d just walked off the tennis court after a strenuous match, which incidentally, he thought, she would have won.

“Is this your first time?” he asked. Guessing at her age, he interpreted the perspiration as nerves.

She laughed, her flushed face smiling. “No. I’ve been doing it forever.” She dabbed at her forehead with a tissue. “It takes a lot out of me, though.”

He was surprised at the slight lilt to her speech. “Not American?”

“Half-breed.” She plopped into a chair. “My mother is American, deaf. My father, Lebanese, deaf, but we left Lebanon when I was sixteen.”

“That explains it.”

She crossed one leg over the other, raised her eyebrows and waited.

“The native signing, the slight accent in English. You look thirsty. Can I bring you some water?”

She nodded. When he came back with the plastic cup of water, she took it and drank it in one swallow. People were still trickling out of the auditorium in groups of two and three. The importance of the FoxP2 paper from the day before was being debated around industrial-sized coffee pots. Camps were forming. There were those who believed FoxP2 to be the holy grail, the genetic tool that would allow bird research to flourish as mice research had, and there were the skeptics who cautioned restraint. Tomorrow there would be break-out sessions to discuss the implications of the gene. Normally, David would be standing side by side with them at the coffee pots, debating as well.

“I recognize most of the interpreters here. That’s why I thought you were new.”

She shook her head. “Not new, just lazy. I only work a few months a year.”

“What do you do the rest of the time?”

She laughed. “I live.” She glanced at her watch. “Show time.”

He hadn’t planned on going to the next session, but he followed her and watched her move with the words, mimic the sounds and lack of sounds with her body. Her trance-like exhaustion returned him to a nagging question, and he began to wonder about effort and cost. At the end of the session, David’s brain was in hyper mode. He often watched male zebra finches move down the perch toward a female, swinging their bodies left and right and grasping and then un-grasping their toes as they went. They would stop in front of the female, ruffle their feathers, cock their heads one way and sing. Did that hopping, courtship dance, which he’d always ignored, have anything to do with their song? How much energy might the dance take? Did it add to the cost of singing? These were the thoughts he was thinking when he noticed that she was also looking at him. When she signed “follow me,” he stood up and followed.

“You were watching me,” she said.

“Not a hard thing to do.” He blushed.

They made their way through the crowd of scientists, people identified by name, institution and rank with white nametags pinned to their chests. They waited at the elevator, looking at one another before glancing at the mirrors flanking the doors, each watching the other’s reflection.

“You understand sign language?” she asked.

“Some.” He hoped she didn’t ask why or where he’d learned.

Inside the elevator she pressed the button for floor ten. “It’s the perfect job for me. I sign better than I speak. The direction is natural.” They walked down the hallway and she stopped at the door of her room. “A drink.” It wasn’t a question, just the utterance of a confirmation, something already understood between them.

Once at her room, she gave him options: vodka, whisky or gin. He chose gin, she drank whisky. Quickly, he noticed. She excused herself to the bathroom. He took in the room, incredibly bland, marveling at how it countered his state, the excitement he’d felt during the previous day’s sessions about FoxP2 and now with her. When she came out a few minutes later, her hair still in a short pony tail, she was dressed in a robe and then, as if she’d known him for months, she slipped it off.

Shocked at her naked body in front of him, he began to speak, the beginnings of an utterance, but she quickly raised her fingertips to his lips. “No.” she signed. “Undressed, no talking allowed.”

She held out her hand for him. He stood. She smiled, unbuttoned his shirt, undid his belt, removed his pants, his shoes. She pulled back the bedspread and sheets, signed “lie down.” He stretched out cautiously on his back. She sat next to him on the edge of the bed. She spoke slowly, signing out what he should do, how he should touch her, how she planned to touch him. These were the words he understood. There were other phrases he was less sure about, and might have imagined: Mouth over you, your tongue in me. And there were movements he didn’t recognize as words, the way she brushed her fingertips over herself, touched her own breast, her lips. He reached out and took her hands in his, stopped her from saying more. They remained motionless for a moment longer, her sitting on the bed next to his prone body, hand in hand, eyes on eyes. Language rendered useless.

The intensity of this memory created a quick flush in David’s body. He took another sip of coffee, shook it off and focused back on what he’d been telling Anton.

“A family, the KE family, was brought to some British scientists. For over three generations about half the people in this family can’t speak properly. Their speech is essentially unintelligible and they’re taught sign language instead.”

“What’s wrong with them?”

“It’s incredible, a single mutated gene.”

“A single gene controlling speech?”

“That’s what the Brits said and so the popular press and science magazines were swarming all over the conference. They were calling it the language or grammar gene.”

“But you don’t believe that?”

“No, of course not. There can’t be one gene for grammar or language, just like there can’t be a single answer for memory.” David’s voice went up an octave, “Engrams do not exist.”

Anton didn’t respond.

“Seriously Anton. Anyway, it doesn’t need to be the language gene to be interesting. What’s cool is that this gene has a forkhead, and the fork codes for a transcription factor and because transcription factors turn things on and off, it has the potential to affect the expression of a lot of genes.”

“And?”

“Having a mutant means there’s the potential for experimentation. Once the research progresses a bit further, we might be able to use FoxP2 in our auditory feedback experiments.” David laughed. “You should have been there, though. It was a feeding frenzy. The reporters were saying they found the reason for the evolution of humans. Supposedly, this gene enabled us to speak, which in turn allowed us to evolve into the superior creatures we are. Utter rubbish, but I guess everyone, not just you, Anton, is looking for some kind of holy grail.”

“Not a holy grail, David. Just some data, a few published papers, maybe eventually a job and someday a vacation to one of those tropical places where I really will hang out on the beach.”

David laughed and set down his empty coffee cup. He thought of Sarah. “Vacations are overrated.”

David woke in the faint blue gleam of his office, taking a moment to remember where he was. He lay for a few more seconds allowing his eyes to adjust before unzipping his sleeping bag and getting up from the cot. He didn’t think that anyone knew he slept in his office two or three nights a week and he preferred to keep it that way, although if he were ever asked, he could always use the winter weather as an excuse for not driving up the snowy canyon to his home.

Outside there was a layer of late spring snow and the dark city was sparkling. From the institute, nestled in the foothills, he could see the flashing yellow lights of snowplows working their way through the streets. He loved the fleeting stillness of the laboratory when he woke in the morning knowing that in a few moments, when he flipped the light switch, the birds would come to life, fluttering and squawking. Silence to sound. And then later at night, when he turned out the lights again and there was only the glow of the computer screens, the birds would quiet once more, tucking their heads to the left or right to sleep.

He rolled up the sleeping bag, tied it, and stored it in a bottom cupboard. He folded the cot in half, balanced it against the wall and then opened his office door to keep it in place. He switched on the light and checked his watch. 6:30 a.m. He glanced at his calendar knowing already that Rebecca and the undergraduate students would come in two hours, and he noticed, once again, the unopened letter from Sarah postmarked from eastern Peru where she’d gone back in a futile search for Ed.

Taking a clean shirt and underwear from a drawer, he went through the dark lab, unlatching the double bolt quietly, careful not to disturb the sleeping birds. He walked down the hallway past the aviary and the experimentation rooms to the shower. When he returned a few minutes later, the dirty clothes bundled under one arm, the red light was flashing on his phone. He punched in his code to listen to the message.

“David, hi, it’s me. Sarah. Look, I’m worried. I’ve been calling for months and despite the time changes, I think I’ve managed to call at every hour of the day. And you never answer, which means you’re not at home even during the hours when you should be, which means you’re working absurd hours at the lab, but now I’m calling the lab and you’re not answering either.” There was a pause. “And well, I don’t know what that means. So please, send me an email or something and I’ll try again.” Another pause. “Okay?”

He heard the click of the phone and then pressed the number four so that he could listen again. Despite being in Peru, her voice sounded clear and crisp, as if she were in the next room, and as always, the clearness brought longing because it had been her voice, the timbre and cadence, that had drawn him first. As a graduate student he would arrive at class early, close his eyes and wait, trying to decipher if he could hear her coming down the hallway and entering the room. Usually she was laughing. In the beginning there was so much anticipation in knowing he would hear that voice and talk with her every day. After they’d begun living together, her verbal ease became the perfect counterpoint to his difficulties with expression, and he became so accustomed to her presence in his life that he’d never feared losing her, her voice, or the ease he felt with her. And then one day, she was gone. The machine’s recording came on and he listened again and this time when he was offered the option to delete or save, he hesitated, and then without choosing anything, he hung up the phone.

His stomach growled. He needed a coffee and something to eat, but that could wait. Sarah frequently complained about his thinness. There’s nothing on you, no reserves. How is your body to keep working when you get ill?

“I rarely get ill,” he said out loud.

Once, just before they’d begun living together, he had recorded her. He’d gone to the university library where she was leading a study session for undergraduates and hidden behind a shelf of books. It was the end of the semester, the undergraduates were nervous about the final exam, and Sarah, being Sarah, felt a great deal of responsibility for them. She had always given more than anyone asked. Even with him, he realized now.

Removing a book, he spied her through the shelves in jeans, a tank top and a man’s white shirt, unbuttoned, sleeves rolled up, her hair pulled back in a ponytail. He slid a small microphone through the space and then hunkered down on the stepping stool to record her speaking, then laughing. Later, he’d filtered out the other students and noises so that he was left with the purity of her voice. He had listened to it over and over late at night back then, like one listens to a great piece of music or a favorite song.

He hadn’t thought of it in years. Where was that recording now? He rummaged through cabinets in his office, emptied the contents of his desk drawers onto the floor. The tape had to be somewhere. Without cleaning up what he’d dumped on the floor, he went into the conference room to scan the bookshelves. He opened the glass cupboards and looked among the scraps of old recording machines he no longer used. There was a rising anxiety at not being able to locate the tape. He tried to remember when he’d last seen it. Had it been the year or two years before? He’d found it and played it for Sarah and they had laughed at his early shy approach to her.

“Not you, just your voice.”

“I should report you.”

Out in the main laboratory he heard the canaries and zebra finches making the first tentative sounds and he remembered that he planned to record their early morning songs today. He could do it another day. The tape was more important. He opened the door to the laboratory, flipped on the lights and the birds let out a single burst of sound, their songs overlapping, mixing and then echoing off the walls and windows, creating a dissonance that mirrored his anxiety. He pulled out drawers, fumbled through their contents before slamming them shut again.

Could Rebecca have filed the tape away? He moved from one laboratory bench to another, opening each of the cupboards below the counters and looking through the shelves. The birds called, sang and fluttered against their cages just above his head. Would Rebecca have known it was something precious, not to be thrown out in one of her organizational cleanings? What if the tape was there, on one of these shelves, but in his haste, he’d missed it? He went back and looked in every cupboard again. He was sweating now, not from exertion but fear.

The birds had quieted by the time he finally gave up his search. Next to the laboratory bench, his back against the wall, he shut his eyes and tried to imagine how her voice would look if it were digitized by the computer. He could call up visual images for at least a dozen birds: harmonic stacks for zebra finch songs, trills for canaries, whistles and buzzes for white-crowned sparrows, but not her. There was the soft call from the Inca dove, the one that said no hope, no hope. Sarah’s favorite bird. He stood and went to its cage, removed the food dish, dumped the old seeds into the trash and filled the dish to the brim with new seeds. Back in his office he sat down, and for the first time since he was a boy, he cried.

David remembered how much Sarah wanted them to visit Ed in Peru. There was no reason not to take the trip, but he hesitated. “I can’t. I’ve got all this stuff to finish. A grant deadline coming up. A paper to submit. You go.”

And so Sarah had flown to Los Angeles and from there to Lima. In Lima she boarded a small plane that went up, stopped briefly in the Andes and then down into the forest at Puerto Maldonado. For the first time in years, they did not have daily contact. David rose alone in the morning, fed the birds at home and went to the laboratory, relieved that he could remain there for however long he liked. Other than knowing the date and arrival time of her flight, he gave little thought to her return. He had assumed that the space between them was temporary.

When Sarah came back from Peru she said, “The forest sounds like a mess of jumbled noises, but Ed can distinguish them all.”

“I’m not surprised.” It’s the only place where I can forget myself, Ed once said. Everything falls away, and I simply become ears that hear.

“He’s so gregarious. You know the weird thing? He speaks Spanish, fluently. Of course, if I’d ever thought about it, I would have expected him to, but before getting off the plane in Maldonado, I’d never heard him say a word in anything other than English. Have you?”

“Come to think of it, no,” David said.

“It’s really beautiful. The first morning I went into the forest just as the sky was beginning to lighten and within a few minutes there was this explosion. A bunch of parrots came flying over me. You can’t imagine how loud they are. Skinner is one thing, but all of these together is quite another. A blitz of sound unlike anything I’ve ever experienced. Awful really. I don’t know how any animal can hear another.”

As he listened to Sarah talking about her trip, the towering trees, the mud, the jaguar tracks they saw early one morning, David’s mind kept shifting, two conversations merging, Sarah’s voice and phrases from Ed in the past.

“Intimacy is established so quickly,” Ed had said. “Perhaps it’s the humidity or the small groups, or the isolation. People come immediately closer.”

David imagined Ed, his eyes continuously scanning the skies, casually noting when a bird passed by. He imagined Sarah watching him as they motored up the river. He wondered about sudden intimacies.

“He asked about you,” she said, “and I told him that you’re focusing on neurons, trying to get to the smallest unit so that you can understand the initial generation of song.”

“And what did Ed say?”

“He said you’re the best at what you do.”

Once Ed had told David about the time he brought a wealthy man and his son up the Tambopata River. “Finnish or maybe Norwegian. I can’t remember. They were quiet, shy people, hardly speaking with one another and so I didn’t try to force the conversation. We’d gone about two hours upriver, the boat cutting through water, the sky hazy, the green forest to each side, when all of a sudden, the driver cut the motor and said my name. I turned and saw that a male jaguar had positioned himself out on a big snag over the water. He was relaxing with one paw over the other, eyes half closed. I could see his eyelashes. We were that close! In thirteen years in the tropics, seeing footprints occasionally, I’d never seen the real thing, and here he was. I took about five hundred pictures in thirty seconds. The Finnish. You know what they did? They took out their cameras, clicked a couple of shots, looked through their binoculars and smiled over at me. I don’t think they had any idea what they were looking at. I think they thought this was normal. You know, you go to the tropics and it’s like going to the zoo. You see animals. You take pictures. You buy a hotdog and go home.”

“Are you listening to me?” Sarah asked.

“Of course.” David refocused on what she was saying.

“I was saying that I felt weirdly lonely there. Small, but a different kind of small than I feel around mountains.”

“Ed once told me that the rainforest was the one place in the world where he didn’t feel lonely,” David said.

Sarah was silent for a moment and then she began to cry.

“Sarah, what is it?” He reached out for her, putting his hand on her shoulder, but she shook her head and stepped away.

“It’s nothing, sorry. I’m tired. It was a long trip. I think I need to get a good night’s sleep.”

That night she had slept in the spare bedroom.

In the small conference room off the laboratory, David sketched a diagram on the white board. Rebecca and the undergraduate students, Sasha and Stephanie, sat at the table, blank pieces of paper before them and waited while he drew. He turned to face them.

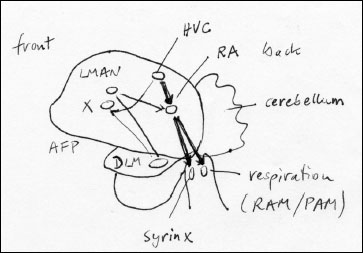

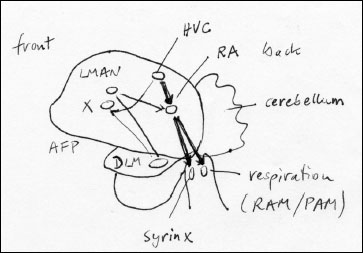

“Nerve pulses originate here in the HVC.” He circled the region on his sketch in red and drew arrows over what he’d just drawn, outlining the pathways that controlled vocalization. “What we hear as song starts out as information passed as action potentials from one group of cells to another. These electrical impulses travel in super speed down the axon from cell to cell.” He circled the HVC region again. “So, the action potentials start here in the HVC, pass to the RA, and then to the syringeal motor nucleus in the brain stem, which then sends a signal along this motor neuron to flex the muscles around the syrinx.”

He glanced at them. Stephanie and Sasha nodded their heads, but looked lost. Rebecca, as usual, was following without difficulty. He began to re-label the diagram, spelling out high vocal center for HVC, sketching out a new image of the trachea that branched into the syrinx.

“The bird’s syrinx is like your larynx,” he told them. “When you exhale to speak, air is pushed from your lungs past flaps of skin in your larynx. The flaps vibrate and create waves of sound.”

“Here, Rebecca,” he said, placing his fingers softly against the front of her throat. “Pretend you’re in a doctor’s office. Say ‘aaaa.’”

She voiced “aaaa.” He lifted her hand from the table and exchanged her fingers for his. “Do you feel the buzz?” She nodded. The other students began to “aaaa” as well.

“The buzz comes when the vocal folds partly cover the opening in the larynx called the glottis. Now make the sound lower. Now higher.”

The students did as they were told.

“For lower frequencies, the flaps are further apart, vibrating more slowly. For higher frequencies, they come close together and move very fast.”

Whether in humans or birds, every exhalation was a potential sound. The folds pulled in and vibrated. Or they did not. But unlike in humans, in birds the right and left sides of the syrinx could be controlled separately by nerves coming from left and right sides of the brain. David could snip a bird’s left syringeal nerve and instantly, the low frequency sounds were gone and the bird’s song shifted higher.

“From the syrinx,” he continued, “waves of air travel up and out the beak.” He drew a blue line for air from the syrinx, up through the trachea and out the beak. “Beaks function something like our mouth, tongue and lips to filter out certain frequencies, to create resonance.” He noticed that Rebecca had straightened herself in her chair. “Beaks held wide open enhance high pitched sounds. When the beak is more closed, the sounds are lower.”

His ultimate goal was larger. It was true that he wanted to know how a bird sang, how the impulse to make sound had been organized throughout millions of years of evolution, how air was pushed past the syrinx making it vibrate, but those were only the technical parts of the story, the relatively easy things to know, the questions he could pose in grant proposals and be sure, at least up until this year, to secure funding for. These were the questions that had kept his laboratory running for the last decade, kept the students busy with projects, but not the ones that kept him awake at night, not the ones that had drawn him to biology.

As a teenager he had walked a daily loop around his neighborhood. Behind the row of new houses, there was a field of undeveloped land bordered by a copse of trees, a small stream and a pond, the relics of a farmer’s property. He knew what he was likely to see and hear, knew at which spots the chipmunks and squirrels would rattle at him, which thrushes would flush from the ground as he approached. But some days there were surprises. Once he came upon the pond and found a purple gallinule standing still, one bright yellow leg bent, the other in the water. He stood frozen and watched as the gallinule made its way across the pond, poking its head into the water to eat, staying until the bird stretched its iridescent wings and took off. The next day he set out with great hope to see the bird again, but it was “an accidental,” a bird blown off course. He would have to wait until graduate school in the south before he would see a gallinule again.

“Rebecca, I have a project for you,” he said later that day.

“The aviary? I cleaned it yesterday.”

“No, a research project. You can do more than clean cages. You ask good questions and you’re good at handling the birds. I have to go to New York to give a seminar but when I return, I have a project for you about the cost of song.”

“What do you mean, cost?”

“Probably one of the biggest unanswered questions in birdsong. Imagine you’re a male bird singing to attract a female. How much oxygen and energy does it cost for you to serenade?

“It would depend on the lyrics, wouldn’t it?”

David smiled. She had the same freshness, ebullience, curiosity about the world, and raw smarts as Sarah.

“True. That’s what people have been looking for. Song structure, complexity, but what if structure doesn’t matter? I mean what’s probably more important are the indirect costs, not the oxygen consumed, but every moment spent singing is one less moment for foraging or nest building. Not to mention the fact that every time he sings, he’s giving up his location to the predators.”

“I get that, but what I meant was,” Rebecca said, “maybe a trill is more expensive than a whistle.”

David looked at her again. No one had ever considered the cost of different syllable types, and he didn’t have any idea how he’d test such a thing, but she’d made him think. “Interesting,” he said. “Very interesting. I’ll think about how to test that on the plane tomorrow and we’ll get started when I get back.”

At five hundred miles an hour, the plane burned through the clouds, the jet engines leaving a trail of iced water behind. Stanley Sommers, his friend from their post doc years, had invited him to New York for a seminar. Outside the window he saw white.

He had just read that women preferred men with lower voices, especially around their time of ovulation. A curious finding. The evolutionary psychologists would have had a field day with that, concluding in their strict Darwinian way, that the preference was easily explained. In ancient humans, low voice equated with bigger men and bigger men were bound to be better protectors. As easy as that. In birds, he didn’t think pitch had much to do with it but maybe trills. Yes, Rebecca reminded him of Sarah, only Rebecca was quiet where Sarah was expressive. And then he reminded himself that Sarah’s gift for verbalization next to his inability to talk about his feelings, was probably half the reason she was gone. The other half, he didn’t want to think about.

The airplane was trembling, bumps of turbulence, pockets of higher and lower pressure air shook the plane like a toy. He looked away from the window and closed his eyes to the shaking. Was a female bird really more attracted to one song than another? Could she tell the difference? If so, how did his singing bring her in? The shaking stopped. He opened his eyes and looked out. They had come out of the clouds and he could see the land below. At this time of year, the tilled fields of the Great Plains were dark brown sprinkled with snow. From the height of the plane it looked as though a gigantic starling in white-spotted winter plumage had spread its wings upon the earth.

David’s seminar was a success, only he made the mistake of agreeing to stay with Stan, his wife, Helen, and their two children in their small New York City apartment. He was required to sit through noisy dinners in the cramped space with pre-teenagers and answer Helen, who bombarded him with questions. She asked about Sarah first, of course. David answered that she was fine. And she was. He just didn’t see the need to explain that they were no longer living together, that Sarah was probably, right now, hiking through the rainforests of Peru, tanned and sweaty, some ruddy, equally sweaty man by her side. He was grateful that the two couples hadn’t known one another better in Pennsylvania, the post-docs having divided out neatly into those who had children and those who did not. A lie of omission was unlikely to be found out but Helen wasn’t satisfied with bland answers and kept on with more questions. Like a dog on the trail of a pungent wild pig, he wondered if she could smell his loneliness. Fortunately for David, Stan was bored with Helen’s personal questions too. “So, David, let me tell you about the spin-off we’ve set up. You remember the paper I published in 1985? About the configurational changes to neurons during memory creation and retrieval?”

Helen excused herself.

“You mean the theoretical one about engrams that you’ve never been able to shore up with data?” David asked. He reached for the bottle of wine. Perhaps he’d be able to tell Anton that Sommers himself was giving up on the idea.

Stan laughed. “Right, that one. Although that’s about to change too.”

David set the bottle down quickly, his glass still empty. “You’ve got them? You’ve seen it happen?”

Stan was nodding. “Crystal clear. I’ll show you tomorrow, but it’s under the radar. This time we’re going to be extra sure before we release it.” Stan was smug. He reached for the bottle, took it from David’s hand and refilled both their glasses.

“But that’s not what I’m talking about. I’m talking about business ventures. Ever since Bayh-Dole, it’s been worth our while to invest in business, only most of us didn’t realize it. Now there’s real incentive. On top of knowing you’ve found a way to beat big diseases, there’s actual money to be made.”

“I’ve never been interested in business spin-offs, Stan. You know that.”

Stan took another sip of wine, letting a brief silence precede what he was going to say next. “We’ve got a new drug that enhances memory. It’s passed Phase I trials and has been accepted for Phase II, and you know what, David, it really works. It’s going to revolutionize the way we treat all sorts of age-related memory loss. Attention deficit disorder, too. In a couple of years Ralph and his research team will be done, dried up.”

Ralph Krest, premiere neuroscientist, memory expert and Nobel Prize candidate, had said Stan’s configuration theory of neuronal memory—the existence of engrams—was nothing more than wishful thinking. David had always agreed with Ralph but he’d never voiced his opinion to Stan.

The wine had made Stan more exuberant than usual. He might be getting a little ahead of himself, but his vehemently competitive spirit reminded David how pleased he was not to be Stan’s direct competitor. As it was, he knew Stan felt him to be a non-threatening colleague, a smart one to be sure, but someone who’d chosen the wrong animal to study. Stan believed that unlike mice and rats, birds would never reveal the essence of the human mind.

After three days with Stan, David was sick of New York. He didn’t understand how people could make it through the winter locked in by the tall buildings, the sky as grey as the wet streets. He was relieved when he boarded the afternoon flight out of JFK. Weary of questions from undergraduate and graduate students, he looked forward to the comfort of his own lab. They had asked: Where would neuroscience be in ten years? Would there still be enough subject matter for a student today to build a career on? Did he think there would be a neurological cure for Alzheimer’s? He’d forced himself to answer politely, to not say what he really felt, which was he didn’t know anything about an Alzheimer’s cure and he didn’t care that he didn’t know. He didn’t care about human diseases or how neuroscience could make life better. All the while he was responding to their youthful eagerness, he was hearing Stan in his pompous way.

“I tell you what you do. Forget the post-docs. You get three grad students for the price of one post-doc, four depending how your department supplements the funding, and you put them all on impossible problems. You shoot buckshot and chances are you’ll bring down something.”

Buckshot. He wanted to tell the students about Stan’s philosophy. Don’t you know you’re nothing more? Go find a lab where your time and energy isn’t the whim of a gambler. Sarah had never cared for Stan. A classic narcissist. He talks about himself constantly, his research success, his new house, even his physical workout schedule!

David didn’t know whether Stan was a narcissist or not, but he definitely was a bore. What he thought now, as the plane passed over the Rockies, was that he might have told the students the truth—that the only question worth knowing was this: How much does it cost a bird to sing and why do females think that some males sing better than others?

Rebecca hadn’t touched her camera in months but today, after she left Anton sleeping in bed and scribbled a short love note to him on the counter, she’d gone home to get it and carried it with her to the institute. She swiped her identity card through the magnetic strip and when the green light flashed, she pulled on the door and entered the cold stairwell. With a flick of her head, she knocked back the hood of her spring jacket and went up the stairs, her footsteps echoing in the hollow space, the crisp air pushing at her back. Three flights up, she opened another door and stepped into a broad hallway flanked by massive windows. This six-floored, rectangular glass building felt like a fishbowl. Down the hallway she passed four black leather chairs set around a pink granite coffee table. In the months since she’d been hired, she’d never seen anyone sitting in the chairs. Three science journals lay in a fan across the table, the cover of the top journal showed a bird singing. Outside the laboratory door she dug into her jeans pocket for a key, but even with the door closed, she could hear the muffled calls.

“Uncovering the rules of speech,” was how David explained the work. She pulled on the heavy door, propped it open, and stepped around empty cardboard boxes and outdated electrical equipment.

The zebra finches, noisy, feathered holders of this speech secret, stacked two stories high along one wall of the laboratory, chattered loudly with her entrance, flitting on and off their perches, squawking, eating and fluttering, scattering seed grains everywhere. She was mesmerized by these small gray and white birds with their quick robotic movements, intrigued by their calls and songs, their necessity to make sound. Do they understand each other at all? Today when she was done feeding them, she would take some pictures.

She dug into her bag and pulled out the chocolate bar she’d brought for Anton. In his office, she drew a large heart on a piece of paper and placed the chocolate on top.

Back at her cubicle she took off her coat and looked out through the massive western-facing windows, glazed with gray film to protect against the afternoon sun. From this perch on the foothills she could see the entire valley: the university campus below her, the white dome of the state capitol, the Oquirrah Mountains to the west. The Great Salt Lake, on this clear morning, was a whitish blue line. She gathered her long red hair and twisted it up along the back of her head, holding it in place with two pencils from her desk, and tucked the shorter strands around her ear.

As she approached the row of cages a zebra finch opened his scarlet-orange beak to sing and the rest of the males, as if on cue, joined in, repeating the same nasal harmonic bleeps over and over. She watched them for a moment before she began to slide the cage doors up, one by one, to reach in and pull out the half-empty, plastic water containers. She drew out the seed containers too, tipping the seed hulls into the trash and then tossing all the containers into the large black sink for washing.

While the water filled the basin, she went back to one of the zebra finch cages, having noticed that one of the birds had a strange looking feather. Checking that he was okay, she raised the gate and inserted her hand. The four birds fluttered up and back, calling out against this intrusion. The entire laboratory of zebra finches joined in their anxiety. She easily cornered the bird in her palm and removed her hand, too quickly though, rubbing her wrist on the way out against a sharp wire on the cage door.

The room went quiet again. Flutter like shutter, she thought. The shutter of a camera, brought about by the pressure of her finger as she let out a breath, her left eye accepting the momentary blackness of a long blink. It had been a while since she’d assumed that posture, a while since she’d looked at the world one-eyed through a camera lens. She squinted now at the bird in her hand drawing out his wings to inspect each feather. A bead of blood had seeped from the scrape on her wrist and she brushed it away.

Being in a space with the birds these past months had made her realize how mysterious their world was. She’d become convinced that they had secrets to tell and not just about communication. She was sure of it. They were made of air. Air moving constantly through buoyant air sacs, waves vibrating through the syrinx, up the trachea and out the beak. Their hollow bones were light for travel. They were sound ruffling through feathers. Their physiology was more dinosaur than mammal. Beacons of the past, they were meant to be free.

What had Anton said? Humans had a brain and an opposable thumb and technology and just having all of that made it alright. She would ask David what he thought when he got home from New York, how he justified the rights he had and the work he did. Certainly he’d have a better way of explaining himself than Anton. More of a visual thinker than a talker, she couldn’t quite put words on her thoughts, but deep within her she felt that Anton was wrong about the birds. It couldn’t be as simple as he made it out to be. He had shrugged his shoulders, as if he didn’t care, and said, We’re all in a cage to some extent.

She stopped scrubbing the seed and water dishes and looked around the laboratory. She closed her eyes so that she could hear better. What were they trying so hard to say? That they should be free to live and die as they chose? Now with the muting technique, they wouldn’t even be able to make sound and so she couldn’t hope to understand. She felt the stirrings of a new, fiercely awful thought. A feeling of dread. She’d been wrong about someone before. What made her think that she had any more insight now? And if Anton was wrong about the birds, then was she wrong about him?