3

Confinement at Cape Adare

9 February 1911–4 January 1912

THE NORTHERN PARTY – as it was now permanently and properly known – set sail again on 9 February 1911. Ponting described their departure: ‘We stood on the shore watching them until the boat was hoisted aboard. Then the good ship dipped her ensign, and, with three blasts of her whistle in salute, she stood away to the northward.’ Those left at Cape Evans would not see the familiar outline of Terra Nova on the horizon for a long twelve months.

Campbell’s instructions from Scott had been clear and unequivocal: ‘The main object of your exploration in this region [Robertson Bay] would naturally be the coast westward of Cape North.’ This was because no one had yet succeeded in landing on this outpost of South Victoria Land, where the great Admiralty range of mountains plunges down to the sea. Pennell, once he had dropped them off there, had been instructed to explore the shoreline still further west until forced to leave for his overwintering in New Zealand.1

In 1841 Ross had thrown down a tantalising gauntlet: ‘We had a very good view of Cape North whilst close in with the icy cliffs, and observed that a high wall of ice … stretched away to the westward from the Cape, as far as we could see from the mast-head, and probably formed a coast line of considerable extent: a close, compact, impenetrable body of ice occupied the whole space to the northward and westward.’ Behind, ‘the lofty range of mountains appeared projected upon the clear sky beyond them beautifully defined.’ Exploration here would be a reasonable compensation for the loss of King Edward VII Land.

The Northern Party had to reach their destination with all possible speed, as the ship’s supplies of coal were running low. But their run of bad luck continued: from 12–15 February the ship was lashed by gales and pushed nearly 100 miles north of Cape Adare, opposite Smith’s Inlet. Dickason commented breezily: ‘Hove-to in heavy sea, ship rolling very heavy, good old tub, heavy snow at times, we must be some way to the N.W. of Cape Adare by now, things are a bit more lively now.’ The following day: ‘Tonight it looks as though it would like to ease up a bit, if it don’t and at this rate we shall soon be back in New Zealand again.’

They found nowhere to land on the precipitous and heavily glaciated coast from Smith Inlet to Cape North. Ross, scanning the coastline from the crow’s nest, had thought the two deep adjoining bays of Smith’s Inlet and Yule Bay promising. He had soon been disabused: ‘The line of coast here presented perpendicular icy cliffs varying from two to five hundred feet high, and a chain of grounded bergs extended some miles from the cliffs.’

In the third major volte-face in the story of the Eastern-cum-Northern Party journey, Terra Nova was forced to retrace her steps and work her way anti-clockwise round Robertson Bay. There was no possible landing place on the ice tongue of the Dugdale Glacier;2 Duke of York Island was inaccessible. Time was running out. Cape Adare was the only place where they were assured of finding a base, and then at a single spot – Ridley Beach, a flat basalt area strewn with pebbles, nestling against the sheer 1000-foot cliff face. They now faced an unpalatable choice: either they could settle for Cape Adare, or they could take a gamble and head back towards Cape Evans, aiming for the virtually unexplored and geologically interesting Coulman Island or Wood Bay. But if they were unable to land at either of those two places within the next three days, they would have to return with Pennell to New Zealand for the whole of the winter.

It was a dilemma, but there was no real contest. Their decision – or rather the decision taken by Campbell after consulting first Levick and then Priestley – was unanimous. They would go the farthest north they could beneath the great bulk of the Admirality mountains in Victoria Land and hope to build up a respectable body of research and exploration. It was a decision that Campbell was despondent about at the outset, and that he came bitterly to regret.

By 1911, Cape Evans and McMurdo Sound had become indelibly associated with the names of Scott and Shackleton, of Discovery and Nimrod. Cape Adare and Robertson Bay had their own ghosts – those of the Southern Cross expedition of 1898–1900, which had made polar history by being the first to overwinter voluntarily on the Antarctic continent. The Norwegian Carsten Borchgrevink had led the ten-man team, with Louis Bernacchi, a young Australian meteorologist and magnetist, as his second-in-command. Ghostliest of all was the party’s zoologist, Nicolai Hanson, who had died during the expedition and been buried in the lee of a large boulder on the high plateau of Cape Adare.3

Borchgrevink was thus well known in polar circles, although rather more as a liar, mountebank and trouble-maker than as an explorer. He was an incorrigible fantasist – about his education, his qualifications and his achievements – and had made powerful enemies. Early in Borchgrevink’s chequered career, Dr H. R. Mill, Librarian of the Royal Geographical Society, described him as ‘of the most irrepressible persistency in gratifying his ambitions’, while Dr Roy Lankester, Director of the Natural History Museum, called him ‘a person with whom one would gladly have no dealings’. Most unfortunately for Borchgrevink, he also put up a black with Sir Clements Markham, President of the RGS, whose word in polar circles was law, and who evidently regarded him as a cross between a knave and a fool. Yet at the time his dogged determination and undoubted courage won him some admirers, and in 1930 the President of the RGS, Sir Charles Close, belatedly awarding him the Patron’s Medal, was to acknowledge that Scott’s Northern Party had made them realise that ‘the magnitude of the difficulties overcome by Mr. Borchgrevink were underestimated … we were able to realise the improbability that any explorer could do more in the Cape Adare district than Mr. Borchgrevink had accomplished’.

Borchgrevink’s account of the winter spent at Cape Adare was criticised, by Campbell among others, as lightweight and inaccurate, and for leaving out facts which might have been useful to future expeditions, whereas Bernacchi’s fuller and more considered narrative was widely praised.4 Scott and other members of the Discovery group, including Bernacchi,5 had landed at Cape Adare in 1902 on their way to McMurdo Sound, visited Borchgrevink’s hut and read his letter to the commander of any subsequent expedition. Already prejudiced against the Norwegian, they had ridiculed his claims, his sentiments and his grammar. Bernacchi, who was of the party, had remained loyally silent about his erstwhile leader.

Cape Adare lies at the end of a 20-mile-long peninsula sticking out like a bony thumb at the eastern end of the Admiralty Range, 2,500 miles from Australia and subject to every vicious weapon in the Antarctic armoury. Bernacchi had been struck by its dramatic topography, exposed to every freak of weather:

As the Northern Party’s predecessors had warned, however, the dramatic beauty of their surroundings was a colossal drawback. The mountain range encircling the Cape Adare peninsula and Robertson Bay justified its formidable reputation: ‘Rising to an average height of about 7,000 feet, and partly free of snow on its northern slopes,’ Bernacchi had commented ruefully, ‘it presents an impassable barrier to a sledge party.’ The inland ice plateau visible beyond was tantalisingly inaccessible, as Campbell was fully aware: ‘I was very much against wintering here, as until the ice forms in Robertson Bay one is quite cut off from any sledging operations in the mainland, for the cliffs of the peninsula descend sheer into the sea.’ Viewing the scene from Ridley Beach, Levick corroborated this pessimistic assessment:

Although Borchgrevink and two companions had succeeded in penetrating some way into the interior, both on Cape Adare and at the southern end of Robertson Bay, where they had used the glaciers as escalators to gain the land mass behind, their sorties had been limited in duration and extent. Above all, they had failed to explore the area around Cape North, the conspicuous snow-covered bluff noted by Ross in 1841. He had (erroneously) thought it to be the northernmost point of the region, and it would make a satisfying area of study for that reason alone. This had been Borchgrevink’s fault. Bernacchi, delivering a paper to the Royal Geographical Society on the topography of Victoria Land in March 1901, had replied to a question from the floor: ‘I am very sorry to say that no expeditions were undertaken towards Cape North. I do not know for what reason. The commander was requested to allow permission to undertake expeditions to Cape North by various members of his staff, but for some reason he did not grant that permission. There is no doubt we could have undertaken these expeditions, because the surface of the ice was not hummocky in that direction, and was perfectly secure, and remained so until late in December.’

Borchgrevink’s failure to explore Cape North provided the Northern Party’s dream and great opportunity. Although they could not expect to fare any better in the territory around Cape Adare, locked as they were out of the interior of Victoria Land, they could set their sights on making a valuable survey of the coastline west of Robertson Bay, as Scott had intended. Levick was to write in his diary: ‘There will be satisfaction in our journey across the sea ice, because, rightly or wrongly, Borchgrevink decided when he was here, that the risk made the attempt unjustifiable.’ Priestley was decidedly less sanguine about their opportunities, either scientific or exploratory. He had written in his diary on 17 November, when the Northern Party were forced off King Edward VII Land: ‘I have no doubt that I can find enough work at Robertson’s Bay but Campbell’s surveying work will be terribly reduced, if not cut off altogether by the difficulties of transport. I am much afraid my sledging here will be decidely local & confined to geology.’

Levick described the tantalising view from Ridley Beach:

First they had to batten themselves down for the polar winter.

The Northern Party approached Ridley Beach at 3 a.m. on 18 February. The tide was running strongly in the bay, pockmarked with pack and fringed by pancake ice. Levick recorded their uncomfortable landing: ‘Campbell & I pushed off in one of the whaleboats with a few seamen and pulled off for the shore. We found considerable surf breaking over a fringe of stranded floe ice along the beach, so we had to set our teeth, and at the word “jump” from him, he and I jumped from the bows, up to our waists in icy water, and after hauling the boat up a little way and leaving the men in her, we ran onto the little peninsula under the cliff.’

The ship carried with her the carcass of the hut that they had intended to erect on King Edward VII Land. They were also to make use of what remained of Borchgrevink’s living and storage huts – the first of many tangible reminders of the Southern Cross expedition.6 Ridley Beach was a triangular 400-acre gravel spit created by the strong tidal eddies swirling round Cape Adare. The flat, pebbly surface seemed a perfect place for a base camp; deceptively so, as it was plagued by winds from the cliffs behind and currents breaking up the ice in the bay in front. To the million penguins which colonised the area, however, it was an annual refuge. ‘Campbell’s men’, wrote Teddy Evans, ‘might for all the world have been erecting their hut on Hampstead Heath during a Bank Holiday, for the penguins gathered in their thousands around them in a cawing, squawking crowd.’ Before they laid the floor of their new hut, Levick tried to bleach out the pungent smell of guano7 with chlorine, nearly temporarily blinding himself in the process.

That first day, the six men and the ship’s crew, especially Davies the ship’s carpenter, worked like dogs for 22 hours, during which time they unloaded the components of the hut, plus 30 tons of stores; the next day work started shortly after 7 a.m. and continued till dusk. Then, with little ceremony but heartfelt thanks, at 5 a.m. on 20 February the company stood on the beach to wave Terra Nova off. As a souvenir, Wilfrid Bruce took away with him a heavy brass dog chain left behind by Borchgrevink’s expedition.

hours, during which time they unloaded the components of the hut, plus 30 tons of stores; the next day work started shortly after 7 a.m. and continued till dusk. Then, with little ceremony but heartfelt thanks, at 5 a.m. on 20 February the company stood on the beach to wave Terra Nova off. As a souvenir, Wilfrid Bruce took away with him a heavy brass dog chain left behind by Borchgrevink’s expedition.

Scott’s final instructions had laid down what would happen a year hence: ‘You will not be expected to be relieved until March in the following year, but you should be in readiness to embark on February 258 … Should the Ship have not returned by March 25 it will be necessary for you to prepare for a second winter … In conclusion I wish you all possible good luck, feeling assured that you will deserve it.’

9. Hastily relocated to Cape Adare after finding Amundsen encamped on the Great Ice Barrier, the Northern Party waved goodbye to the ship and its crew on 18 February 1911 in the knowledge that they would not be picked up again for nearly a year. Terra Nova’s fragile lines shows clearly beneath her formidable hull and iron sheathing.

Although twelve years separated Borchgrevink’s and Campbell’s expeditions, the two parties arrived at Cape Adare in the same month, February, within a day of each other, and only a month separated their departures.9 The long year divided itself naturally into four seasons. From their arrival in mid-February until mid-May, the continent was moving from autumn to winter, with sinking temperatures and dwindling sunlight progressively curtailing outside work. From mid-May until the end of July, the sun disappeared and winter bit deep; the men’s world shrank into the interior of their huts. Then, during the first week of August, the sun’s globe showed itself entirely above the horizon for the first time for almost three months, ushering in a series of spring sledging journeys to the farthest corners of their circumscribed kingdom. Finally, in mid-November came the short and blessed Antarctic summer.

After disembarkation, the priorities for the Northern Party were to stow the stores and finish the hut. They hollowed out an ice house for their supplies of frozen meat, but although their first effort disappeared out to sea, Campbell recorded on 1 March: ‘We managed to save the inmates and carried 40 stiff little corpses up to a new and still more beautiful icehouse Priestley built out of cases built in a hollow square, the inside all ice blocks.’10

Although the bones of their new home were assembled that first day, insulation and lashing-down were carried out after the departure of Terra Nova. Their carpentry efforts were workmanlike rather than professional, and made more difficult by the buffeting the components had received on board. ‘Matchboarding’, in Abbott’s view, ‘is excellent stuff if it has not been kicked about; but after being severely handled, as ours was, it makes the air turn a bit blue as it is put up, with cold hands.’ But although it bulged oddly in several places, the hut stood up valiantly against the cyclonic winds sweeping down upon them almost continuously from the heights of Cape Adare, accompanied by tons of drift. They tied the building up like a parcel, with hawsers sunk into a barrel of oil and three anchors cemented into the gravel, which secured it to the ground on all four sides. These cables were their strongest lines of defence: Borchgrevink had noted nervously how the metal stays ‘sang lustily during the fierce squalls … had they snapped we would probably have been shaken up like so many dice in a box’. Sure enough, on 20 March 1911, the Northern Party lost their magnetic observation tent, carried away by gusts of over 80 mph,11 but this was junior league compared with some of the gales that struck just before the disappearance of the sun and the abrupt descent into winter.

The day following the loss of the tent was beautifully calm on land, but a tremendous surf was rolling up the beach – ‘the biggest we have had since we came here’, wrote Levick, ‘and it has brought up enormous blocks of pack ice which are wedged along the beach and form a solid wall in some places over which the waves, laden with brash ice, break, hurling up blocks up to a hundredweight twenty or thirty feet high’. Whatever the disadvantages of Cape Adare as a location, the dramatic changes in weather gave it a never-ending fascination.

Campbell was determined to make the most of the time available before the encompassing darkness arrived. As soon as the hut was completed, the six men quickly assumed their various scientific roles. Campbell put himself in charge of surveying their territory12 and undertaking magnetic observations. Levick was appointed photographer, zoologist and stores officer – and, of course, doctor, although at this stage, as Campbell pointed out, ‘his medical duties have been nil, with the exception of stopping one of my teeth, a most successful operation; but as he had been flensing a seal a few days before, his fingers tasted strongly of blubber’. Priestley’s main duties were geological, meteorological and microbiological. Abbott was carpenter and kayak-builder, Browning assistant meteorologist and assistant cook (and took over from Levick the responsibility for keeping the acetylene gas lights burning13), and Dickason was cook and baker.

Priestley was generous in his praise of his own three ‘adaptable helpers’, Abbott, Browning and Dickason, who threw themselves enthusiastically into the laborious work of data collection, acquiring new skills as amateur scientists. In the foreword to his report on the physiography of the Robertson Bay and Terra Nova Bay regions, published by Harrison & Sons in 1923, he was quite specific about their contribution: ‘The very complete Meteorological and Auroral Record, the collection of thousands of geological specimens, the gathering of a botanical collection which has made possible a Memoir on the lichens and mosses, the compilation of a continuous ice record, have only been accomplished at the expense of a great portion of the little leisure time which they might well have claimed for themselves.’

Spirits began to rise after the depressing circumstances of their arrival had given way to a regular programme. After they had been established for a few weeks, Campbell noted with surprise: ‘It is wonderful how quickly the time is passing. I suppose it is our regular routine, and the fact of all having plenty to do.’ Although not as arduous and exhilarating as the existence they might have had on King Edward VII Land, it was pleasant and fulfilling enough. Campbell’s report in Scott’s Last Expedition gives a reasonable idea of the range of their activities one Sunday in early March: ‘This afternoon Abbott, Priestley, Levick and I climbed to the top of Cape Adare, and certainly the view over the bay was lovely, the east side of the peninsula descending in a sheer cliff to the Ross Sea. We collected some fine bits of quartz and erratic boulders14 about 1000 feet up, and Levick got some good photographs of the Admiralty Range. On the way down I found some green alga[e] on the rocks.’ On that occasion they failed to locate Hanson’s grave, but much later Browning cleaned and levelled it, and worked an inscription in quartz on basalt as a mark of respect to the first explorer to die on Antarctic soil.

Skiing, climbing and walking were other enjoyable ways of passing the time while the light held. Abbott wrote on 31 March: ‘In the evenings I have been up the mountains for exercise, it is simply grand. There is one place I go to every evening, high up amongst the rocks – I sit down & just feast myself on the glorious scenery.’ (Decidedly there was something of Wilson in the petty officer’s make-up.) Another handy walk was to The Sisters, two rock stacks – one tall and slim, the other portly and short – lying about 250 yards offshore from the Cape; the return trip could be made in an hour. The name was derived from a music-hall song:

We are the sisters wot won the Prize

The sisters Hardbake with the Goo-goo eyes

My name is Gertrude and mine is Rose,

We shan’t be single long I don’t suppose.

The meteorological measurements taken by Priestley, Browning and occasionally Dickason were the most time-consuming part of their scientific programme, occupying many waking hours each day with thermometer and barometer. As in Borchgrevink’s time, measurements were taken every two hours. In fine weather it was just another chore, but in blizzard conditions the observer was lucky if he escaped a lambasting from stray objects hurled at him by the wind. Sometimes it took the unfortunate on duty fifteen minutes to struggle the 800 yards back to the hut, and then only by hanging grimly onto a guide rope.

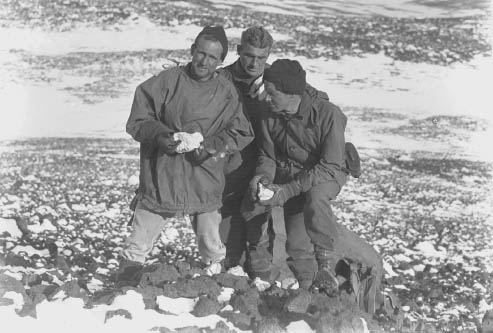

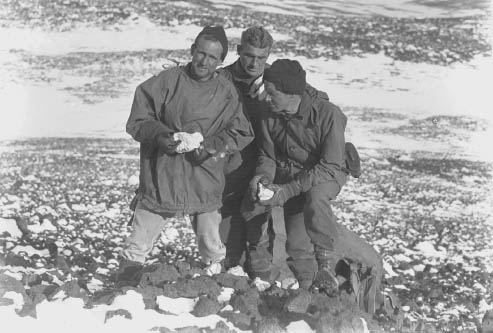

10. Raymond Priestley holding a geology class at Cape Adare. His two ‘adaptable helpers’, Petty Officers Abbott and Browning, became both adept at and interested in the work. They were also called upon to take meteorological readings (chilly) and trawl for marine specimens (unsuccessful).

On occasion Levick helped Campbell with his magnetic observations. He did not enjoy the experience. ‘We do this in a tent under which we have dug a pit, to make room for the legs of the instruments. It is a cold business as you can’t move for fear of moving the Barrow dip circle. If you stir this the whole thing has to be started again. Campbell stood in the middle & I had to squat, half sitting on the snow at the side of the tent. After an hour without moving my position, I could have sat on a spiked iron railing and never felt it.’ Under the pseudonym ‘Bluebell’, Levick later contributed a poem to the in-house Adélie Mail. Entitled ‘The Barrow Dip Circle’, the ending expresses the poet’s opinion of his task:

Then on our frozen limbs we rise

and fill the air with joyful cries.

We’ll go and make a huge repast

the beastly thing is done at last.

The meteorologists of the Northern Party had been taught their trade by an exacting taskmaster, the expedition meteorologist ‘Sunny Jim’ Simpson.15 He had single-handedly raised the money for their state-of-the-art equipment, borrowed other instruments from major meteorological offices, set up the screens around Cape Evans on which the thermometers were mounted, and instituted a rigorous hourly programme of wind speed and temperature measurements which earned him the admiration of his colleagues, a future position as Director of the British Meteorological Office, and the abiding respect of his peers. Simpson’s assistant at Cape Evans, Charles Wright, described him as having ‘a supreme contempt for everything but Meteorology’.

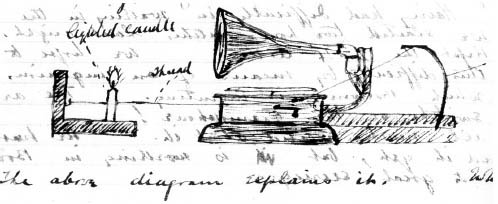

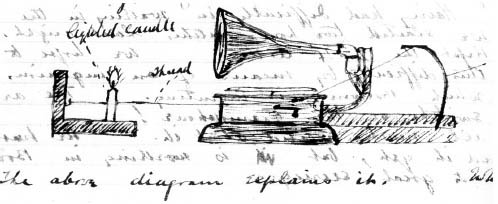

11. Browning’s ingenious musical alarm clock, the ‘Carusophone’, as drawn by Levick in his diary.

The three amateur weather men were later to invent their own unorthodox meteorological aids. Wanting to duplicate Bernacchi’s observations, Priestley decreed that the two-hourly shifts should continue throughout the winter months. Since Levick, who took the 2–4 a.m. shift, regularly overslept, Browning came up with an ingenious musical alarm clock of which Heath Robinson might have been proud. On 17 May Levick reported that they were all agog to find what Browning was working on ‘in great secrecy’ in Borchgrevink’s hut. When the ‘Carusophone’ was unveiled by its inventor a week later, it was found to consist of a candle marked out in hours, a piece of thread and a bamboo cane, all linked to the gramophone. The device was activated by the person taking the midnight observations. Levick described its operation thus: ‘When the candle burns down to the thread, it snaps it, releasing a piece of bent cane which pulls the catch off the gramophone, and starting Caruso off on the “Flower Song” from Carmen which I guarantee to wake the dead, or a man with his head in a sleeping bag, which is much the same thing … This invention works so well that I haven’t worried about producing my own, though think it is really more scientific and exact.’

During an autumnal lull on 27 March they launched their Norwegian ‘pram’ (a light rowing boat) in order to try their hand at dredging for marine life. At this the Southern Cross party had been notably successful, catching all manner of weird and wonderful crustacea and fish. Their own efforts could have formed an extra chapter in Three Men in a Boat, involving a snow-shovel and a wooden bucket to sweep away or smash the ice, a net, a tangle of fishing lines, muscle cramps and swear words. Priestley also made a fish trap, which they lowered under the sea ice baited with penguin meat; this struck bottom at eight fathoms, but they caught nothing. Their total haul for the season being eight whelks, one sea urchin, one polychaete worm and a sea spider, they abandoned marine biology without regret.

Campbell was responsible for improvising the most successful effort in the nautical line – two kayaks, which were built to order by the nimble-fingered Abbott during April and May ready for their spring sledging journeys to the west side of Robertson Bay. Each consisted of a cover laced onto a standard sledge, the first made from canvas tenting material, the second from cotton curtain material. The canvas was dressed with blubber and remained reassuringly watertight. Levick took one out on a trial run, and she rose magnificently to his 12-stone challenge.

They also took soundings, and the beauty of their surroundings made up for the tedium and discomfort of the work. Abbott wrote after one morning’s effort:

Levick was also hard at work photographing the men, the hut, their environs and the magnificent icebergs making their erratic journeys across the bay. He discovered a blanket-lined cupboard in Borchgrevink’s hut which he appropriated for his own use, although it was so cold in this primitive darkroom that he lost all feeling in his fingers; when he was loading slides he had to keep holding his breath or blow it away out of the corner of his mouth, to prevent it crystallising on the surface of the plates and ruining them. However uncomfortable, it was absorbing and rewarding. On 6 April he reported: ‘For the last few days I have been working hard at photography, chiefly illustrating the different formations and curiosities of the ice foot, and at last I have taken a few dozen plates which are quite perfect. Fortunately they are also very beautiful, which is lucky as I have been taking them chiefly for Priestley who wants geological pictures. Altogether I have been at work from early niner till frosty eve, Sunday included.’

Levick was unable to resist continuing his rather bizarre experiments, the precise significance and usefulness of which were unclear. In mid-March he started making a weekly recording of the hand-grip of each man with a dynamometer, boasting with childlike pleasure: ‘and I head the list by a good deal’. He even beat Abbott, the physical training instructor. More usefully, he instituted a weekly weigh-in, ‘as it is very important for us not to get soft’, and proposed to hold a regular Swedish exercise class. Later he and Campbell took to jogging before breakfast, although the combination of rough ground and worn-out boots made this a bit of a trial. Other martial arts were contrived. A punching ball was rigged up in Borchgrevink’s hut, ‘which is a good thing to warm oneself up before starting work in the morning’. Fresh from his triumph with the kayaks, Abbott devised two tin helmets made from biscuit boxes, worn over a woollen helmet, and made some sabres out of split bamboo. Leather mitts protected their hands. ‘I think’, concluded Levick modestly after one bout, ‘I am a slightly better fencer than he is.’

It was a civilised time in the hut. Although the bother of heating water curtailed their washing activities, Levick reckoned that they kept themselves ‘pretty clean on the whole’, and they carried on the Edwardian tradition of dressing for dinner. ‘My favourite costume for this’, he wrote, ‘is sea boots (to the top of my thighs) and my old blue naval blazer with brass buttons, which Priestley declares gives me the appearance of the “Admiral of the Dogger Bank Fishing Fleet”.’ After listening to a concert on the gramophone or dipping into a book plucked from the library shelves,16 they retired to eiderdown sleeping bags reinforced by an inner lining of blankets.

The Sunday service was another fixed point. Campbell and Levick chose two weekly hymns from their limited repertoire of known tunes. On one adventurous morning they tried a new one, ‘Hark, Hark, My Soul’, which Levick recognised from home – ‘some cottagers used to play [it] on the harmonium all Sunday afternoon’. Alas, they had over-reached themselves. ‘When the tune came, after the first few lines I found that my own beautiful bell like voice was singing all alone, the others having dropped out of the running.’ He soldiered on, and the others chimed in intermittently in later verses; they struggled to the end ‘with just the occasional disagreement in the harmony’.

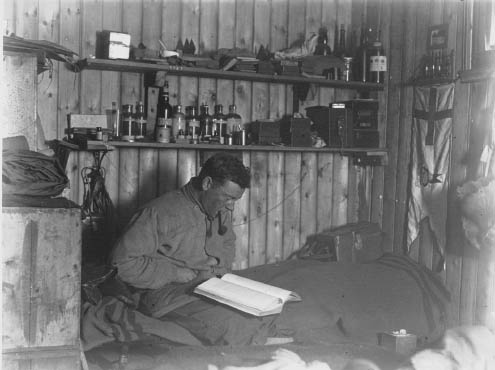

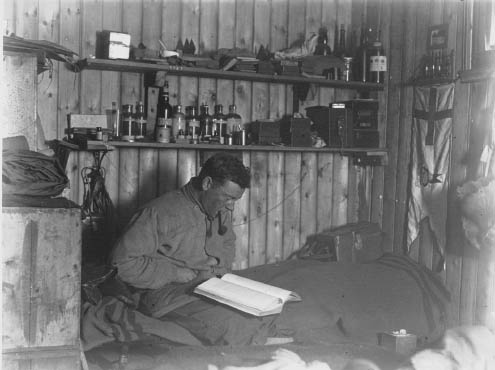

12. Levick at ease with book and pipe in his cubicle at Cape Adare. The naval tradition of segregating the ranks obtained even in these cramped conditions, and would do so when they moved to their final billet underground. The doctor is surrounded by the tools and medicine bottles of his trade, with the sledging flag given to officers at the start of the expedition as decoration.

As autumn began to yield to winter, the temperature dropped and frostbites increased (still a novelty, they were not treated with due deference – Dickason’s rallying-cry was: ‘Just the sort of weather to keep one on the move, “what ho” the noses!’) and tensions began to surface. In early April, Levick reported Priestley in a sulk over Campbell’s decision that all photography must be done in Borchgrevink’s freezing cold hut, where the blubber stove made a mess and was apt to ruin plates. Levick persuaded Campbell to rescind this edict, but had to use his peace-keeping skills a few days later.

Levick dealt with this spat with no-nonsense common sense: ‘I spoke pretty plainly to P. and told him he had put himself absolutely in the wrong, and got him to promise me that if ever he was going to have trouble with Campbell, over complaints or anything else, he would do it privately and not in the presence of men.’ He continued: ‘I have tried as far as possible to make my position rest between Campbell and the others, which seems right as I am no. 2 of the party and ought to act as a buffer to both sides in case of unpleasantness arising.’ It was doubly fortunate that Levick was possessed of a placid, easy-going nature, and that, Campbell excepting, he was older than the rest of the group. Would-be combatants accepted his stepping in with good grace; neither Priestley nor Campbell seems to have felt inclined to shoot the peace-maker on that occasion.

Given Campbell’s irritability, Priestley’s tendency to sulkiness and Browning’s observed shortcomings (‘Browning though very clever and useful, I have already commented on in my account of our ski trip to Hut Point’), Levick was consciously evolving a way to maintain the group on a psychological even keel. He allotted Abbott a key part in this. He recognised the large, gentle and intelligent petty officer’s worth, just as Wilson had done: ‘He is quite one of the most splendid men I have had the luck to know, and I am quite fond of him.’17 Ruminating on the implications of the Campbell–Priestley spat, he wrote: ‘With Abbott to keep the two other men in their place we ought to get on all right, and there isn’t much chance of their losing their heads through living and messing with officers.’

Levick’s strategy was evidently geared to defusing unpleasantness firmly and fairly before personal dislikes took hold and ruined the harmony of the group – he would mediate between Campbell and Priestley, while Abbott prevented unseemly behaviour from the junior seamen incurring the officers’ displeasure. It seems to have worked. On 6 April, after Campbell had been rude to him several times, Levick recorded: ‘as it occurred one morning at breakfast I followed him out of the hut, and as soon as we were alone fairly let him know he had overstepped the mark, and things have been different ever since. We are both excellent friends now.’ He added kindly: ‘He means to be a decent chap and is, on the whole, although rather small minded and lacking in guts.’

It is rare to find such frank comments on record in Antarctic diaries of the period (although Oates’s letters to his mother, for example, are equally revealing about Scott); most are much more discreet, if not downright misleading. It comes as no surprise that neither Campbell nor Priestley mention these two quarrels, and Levick no doubt excised them from his own account in his fair-copy journal.

A fortnight later, he noted with relief: ‘We are all getting along very peacefully now, and C. getting reconciled to P., I think. The latter had been moping a good deal for some time [probably at the thought of the winter soon upon them], but I started pulling his leg continuously at meals, which bucked him up quite a lot, & he has now started to pull mine in return and is altogether quite another person. He works like a nigger at his job I must say.’

He even enlisted Campbell in his therapeutic Priestley-baiting exercises. On 25 April, Campbell and Levick were enjoying an after-breakfast pipe when the doctor noticed Priestley, the only non-smoker of the party, looking disgusted at a habit he considered both revolting and a waste of time. Levick winked at Campbell, who twigged at once, and the following conversation, with a strong whiff of Lewis Carroll about it, took place:

I |

‘I think pipes have distinct characteristics like human beings.’ |

Campbell |

‘Undoubtedly. I once had a pipe that was continuously getting lost. I never had any trouble that way with my other pipes, but this one in particular got itself mislaid nearly every time I smoked it. My keeper knew it by sight, and whenever I smoked it out shooting he kept a special eye on it and as I walked away from each drive, he would pick it up from the ground where I left it behind, & restore it to me.’ |

I |

‘This pipe I am smoking now won’t draw. I cursed it some time ago as it wasn’t drawing properly, and it has never worked well since.’ |

Campbell |

‘That would account for it. One should be very careful how one speaks to one’s pipes, they are so sensitive.’ |

I |

‘Do you think they have souls?’ |

Campbell |

‘Undoubtedly. I think they probably first came into this world as common or garden shilling pipes, and then if they behave themselves well, they re-exist as Benlays’, Loewe’s or B.B.B. own make.’ |

At that juncture, Priestley got up and walked away.

It is interesting in this context to read, in a book written by Louis Bernacchi’s granddaughter, his intimate and revealing diary kept during the Southern Cross expedition.18 Any hint of animosity was expunged from Bernacchi’s own book, but his personal notes laid bare a riveting story of high farce and high drama. Bernacchi took to referring to Borchgrevink as ‘the individual’ or ‘the booby’, and his disgust at his leader’s truly staggering displays of incompetence, cowardice, greed, drunkenness, bluster, lies and egotism rose to a crescendo of fury. Eventually he came to the conclusion that Borchgrevink was, quite simply, mad. Bernacchi’s writings reveal the contemporary lack of knowledge and understanding of the effects of cold, anxiety and boredom on the psychology of the individual and the group. This applied throughout the Southern Cross expedition because of the singular character of ‘the booby’, but the onset of winter was clearly beginning to threaten the harmony of the Northern Party too. Levick was wise to be both concerned and vigilant.

He stuck to his guns over less explosive matters too. He became convinced of the importance of keeping the hut well aired, and insisted from mid-April on opening the inner and outer doors for a few minutes each day, only letting the fug rest unmolested when a blizzard was blowing. Two months later he was still fighting his corner: ‘I have been insisting on our keeping the hut at a decently low temperature … Campbell likes it at a fearful heat. However I got him to agree to 45°F though he wanted it at 50° … unfortunately he really feels the cold more than we do and says he cannot write or do anything in that way at the lower temperatures. What he will do during spring sledging the Lord only knows. Priestley is as hard as nails & doesn’t care how cold the hut is.’

From mid-April, the freezing of the sea – the gradual transformation of evanescent ice crystals into more stalwart saucers of pancake ice and finally into an impenetrable block – marked another milestone in the approach of winter, although individual gales were still able to blast the solidifying ice out of the bay. On 15 April (Easter Sunday), for example, a gale tore in without warning – beautifully fine at noon, fifteen minutes later it was gusting at 60 mph. ‘This is most typical of the Antarctic climate,’ wrote Levick. ‘When the air is still, the sun shining, and everything looking fine and wonderful, nature is simply lulling you into a false sense of security, and crouching ready to spring on you when you can be taken unawares.’

In 1911, as in 1899, the disappearance of the sun in mid-May – the true harbinger of winter – was preceded by an almighty blizzard. On 5 May Borchgrevink had recorded a terrific natural upheaval: ‘The ice-fields were screwing, and at the beach the pressure must have been tremendous. Already a broad wall some 30 feet high rose the whole length of the N.W. beach, and coming nearer we saw that the whole of this barrier was a moving mass of ice-blocks, each several tons in weight. The whole thing moved in undulations, and every minute this live barrier grew in height and precipitated large blocks on to the peninsula … The roar of the screwing was appalling.’ The prolonged blizzard which struck the Northern Party, coincidentally also on 5 May, was of equal ferocity. Levick described it as ‘the most tremendous hurricane we have had yet, or any of us experienced before. The din outside kept us awake half the night, & very often small stones hit the side of the hut with a crack. Some of our outside wall of cases blew down. In the morning … it was impossible to stand up straight in the wind, and one had to drop to all fours in the squalls.’ The 14-stone Abbott was tossed against one of the hawsers securing the hut like a piece of sacking. ‘Lately’, wrote Levick, ‘we have all been laughing a great deal at Borchgrevink’s descriptions of the conditions he met with here, thinking that he was simply piling on the effect, but now we are beginning to feel a little more respect for what he says.’

For Borchgrevink the departure of the sun on 15 May had been an apocalyptic moment: ‘The refraction of it appeared as a large red elliptical glowing body to the north-west, changing gradually into a cornered square, while the departing day seemed to revel in a triumph of colours, growing more in splendour as the sun sank, when the colours grew more dainty, and surpassed themselves in beauty. It imprinted itself upon the minds of us ten so strongly that it made life possible for us through those dark days and nights to come.’

The Northern Party lost the sun on 17 May, but the darkness was not absolute. At midday each day the reflection of the sun’s rays reached them even though the sun itself was below the horizon, and they were granted a period of daylight; only Midwinter Day was absolutely pitch-black. Levick described the scene on 27 May: ‘The skies lately have been perfectly beautiful. Towards noon, we get the appearance of a most wonderful sunset over the region of the horizon where the sun reaches its highest altitude. These “sunsets” have been, lately, various shades of amber, burnt sienna, and gamboge, fading at the edges into delicate apple green and blue.’ Their nights were also lit up by the cold glow of the moon. ‘Imagine’, wrote one observer, ‘a perfectly still evening with forty degrees of frost, the air perfectly dry, and a brilliant moon surrounded by a halo in which the colours of a rainbow are represented twice over, and which shows up perfectly clearly against an indigo sky, while the light of the moon is doubled by the reflection from every point of every ice and snow crystal.’ Bernacchi’s earlier description of these nights had revealed a powerful chiaroscuro element: ‘There is something particularly mystical and uncanny in the effect of the grey atmosphere of an Antarctic night, through whose uncertain medium the cold white landscape looms as impalpable as the frontiers of a demon world.’

The clear skies prevailing during winter also gave the best opportunity to observe the spectacular fireworks of Aurora australis, to which they were treated on most nights. At Cape Adare – situated on the northern rim of the continent (at 71° 185’ latitude) and fairly close to the South Magnetic Pole, where the magnetic activity which generates the displays is at its most intense – they had the best seats in the whole of the southern hemisphere. The show might last from 6 p.m. to 3 a.m., and the 8–9 p.m. slot provided most of the drama.

The officers of the Northern Party would almost certainly have gone through The Antarctic Manual of 1901 – required reading for all polar explorers of the period – and the chapter on auroras must have gripped their imagination. The phenomenon is catalogued in all its guises – an arch of tender light pricked through with stars, a band twisted into intricate convolutions, broad flaming streamers, narrow stripes of red and green enclosing a brilliant white centre, rays flashing and flaring around the magnetic Pole, slender threads of gold woven into a veil, a sea of red, white, green flames … Accompanying the pyrotechnics of light and colour, the author noted the uncanny silence, and also the sense of desolation at the aurora’s departure:

Priestley, who had experienced ‘colourless displays’ at Cape Royds, was not holding out high hopes for Cape Adare. In the event, he could not contain his excitement when describing in his diary what was unanimously voted the finest display of the winter. Although not as extensive as others, it was

These auroras left those who observed them a unique and priceless legacy of movement and colour, but they could not eradicate the boredom and discomfort that was winter life at Cape Adare. Borchgrevink had demonised it as ‘the dark period’, when ‘the sameness of those cold, dark nights attacks the minds of men like a sneaking evil spirit’. At a moment requiring inspired leadership, he was, needless to say, found wanting. For the Southern Cross group, dirt and idleness, punctuated by quarrels and insults, were the order of the winter day. Even in his expurgated version, Bernacchi was unenthusiastic:

By contrast, Campbell’s strategy for dealing with the cold and tedium smacked of his public-school past: firm discipline and immutable routine. Each man had a bath once a week and a brisk snow-wash every morning, although Priestley admitted: ‘I fear it was only a spirit of emulation and a desire not to be outdone by Campbell which kept me up to scratch for the greater part of the winter.’ The daily pattern was described by Levick as follows:

Meals consisted of many of the same staples as those enjoyed by a middle-class Edwardian household, with porridge, potted meat and plum duff putting in regular appearances among the seal and penguin steaks and cold roasted skua. Alcohol was strictly rationed to a glass of sherry or port on Saturdays in which to drink the traditional naval toast of ‘Sweethearts and Wives’. On birthdays the allowance was more liberal, and Campbell was certainly stretching things when he ordained that a bottle of sherry be opened to celebrate the Fourth of June. But on 22 June all the rules were waived for Midwinter Day. There were parcels from home, decorations, a formal and satisfyingly large champagne, brandy and crême de menthe dinner, with cigars and crystallised fruits on the side, and an extended sing-song.

On Saturday mornings the ‘men’ scrubbed out the hut, while the afternoons were devoted to running repairs. On Sundays work was suspended. Breakfast was put forward an hour to give the cook a lie-in, a church service followed at 10.30 a.m., and, moonlight permitting, a brisk walk took them along the coast or up to the icebergs stranded near the beach, all under the clear winter sky lit up by a succession of magnificent auroras. On 4 July Abbott and Dickason enjoyed an afternoon’s skiing down the slopes near the hut in bright moonlight.

The occasional accident also added spice to life. On 15 June Levick was playing chess with Campbell in the hut, ‘when suddenly, in burst Browning, staggering a few steps towards his bunk, and then fell senseless on the floor’. Levick got him in a squatting position, forced his head between his knees and, when he came round, put him on his bunk and dosed him with brandy and water. ‘I then got the following history out of him. He had been sitting at work [in Borchgrevink’s hut], with stove on and doors tight shut. The fire smoked a lot, and burned dully, and after a time his candle went out. He relit it, and it went out again. Then he felt sick, and came over to the hut, where he collapsed. Diagnosis – carbon monoxide poisoning. So simple, my dear Watson!’19

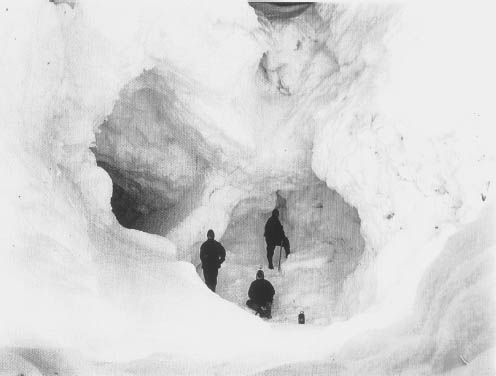

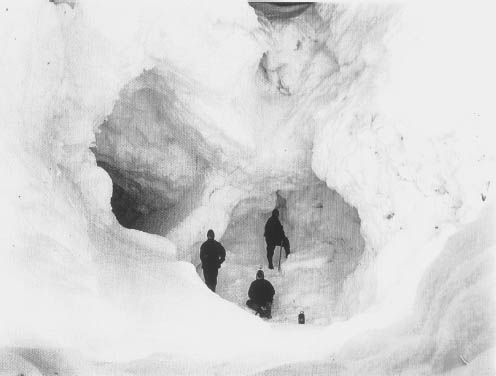

13. Exploring one of the magnificent ‘cave-bergs’ stranded in the sea ice after the freezing of the sea and watching the kaleidoscopic aurora displays were unforgettable aspects of the winter at Cape Adare. Experimenting with magnesium flashlight, while photographing inside a berg, Priestley succeeded in singeing off his eyelids and eyelashes and burning his face.

Campbell’s insistence on creating a framework of order and structure undoubtedly helped to combat the lurking demons of depression and lethargy. Debenham had already categorised him as ‘an instance of that rarity, an officer who could be a martinet on deck and a good companion on his watch below’. The ability to instil respect bordering on fear was a useful tool for an officer, but Tryggve Gran disclosed to Huntford that Campbell had ‘a very nasty temper, and the nickname “the wicked mate” was a right one’. He was certainly a good man in a crisis and good company when things were going well, but long spells of boredom and discomfort were likely to tell on him more than on a man of slower pace and more even temper, such as Levick. By nature extremely shy and reserved, Campbell was a natural target for the sort of dark introspections suffered by Scott. In his obituary, Priestley commented on the considerable mental strain Campbell was under at this time, given the shock of the Bay of Whales and the frustrating limitations presently imposed on the party at Cape Adare. A remark made by Cherry-Garrard about Scott might be applied also to Campbell: ‘Temperamentally he was a weak man, and might very easily have been an irritable autocrat. As it was he had moods and depressions which might last for weeks.’ Like Scott, he kept his feelings bottled up, divulging them neither to his diary nor in his public writings. Priestley was equally uninformative about personal matters. Levick and Dickason alone, in diaries not intended for publication, suggested that there were undercurrents. It would have been strange if there had been none.

There is a hint at this time that Campbell had taken against Levick for some reason – perhaps a legacy of Levick’s reprimand back in April. There is not much to go on, and what little there is takes the form of snide remarks in his diary, such as ‘Levick spends most of his day at photography the results, I am afraid, doubtful as he usually forgets to wipe the lens or puts the plates in the wrong way.’ This might have been meant as a joke, but comments like these are significant because they are not applied by Campbell to any other member of the team. Perhaps Levick’s slow and thorough approach to life and decision-making irritated his mercurial superior; perhaps, as second-in-command, he seemed a legitimate target for Campbell’s pent-up frustration. But the imperturbable good humour which had endeared ‘The Old Sport’ to his shipmates stood him in good stead now, and during the hard times to come.

Priestley was entirely different in character from the two naval officers. Charles Wright, another member of Scott’s expedition and later to be Priestley’s brother-in-law, wrote of him after his death: ‘He had the common touch and he had learned how to obey and to command, a legacy of his days in World War I. But his character was not altogether a simple one. He was unassuming and not without ambition. He was very prompt to inform me whenever he had received any special advancement …’ He was also a good raconteur and a natural diplomat; on many occasions he helped Levick to supply the glue which held the disparate band of men together during the long winter months. He was also enlightening about the character of the Abbotts, Brownings and Dickasons of the period, calling them ‘naval seamen of the long service type, caught young and meticulously trained for many years in a specialized environment … Naval men of that particular vintage were the salt of the earth but they needed knowing and sympathetic and firm handling under the unusual Antarctic conditions.’ He added: ‘I sometimes used to think that he [Campbell] was occasionally too hard on the men for what seemed to be very minor peccadilloes’ – although he went on to retract this remark. Priestley was thinking especially of Abbott, ‘who was always getting into what I thought was too hot water for mislaying gear of all sorts’. Campbell’s handling of his subordinates during that long winter was certainly firm – but knowing? sympathetic? That was Levick’s forte.

The ‘men’ became adept at deception to avoid incurring ‘Mr C’s’ displeasure. Dickason recorded gleefully on 14 June: ‘I very near caused a sensation in camp this morning, instead of turning out when called I lay on and dropped off to sleep again, when next I woke it was a quarter past eight and I had to have breakfast ready by half past, so by flying around and putting the clock back twenty minutes I had things ready when the others turned out. Of course I readjusted the clock at the first opportunity, or at least “Rings” [Browning] did the trick whilst I screened him, very narrow shave. “You blighter”.’

By the end of July all six men, in the prime of life and peak of fitness, deprived of light and cooped up like battery chickens, were sick and tired of their sedentary existence. It was with profound relief and palpable eagerness that they prepared for the spring sledging journeys that would follow hard on the heels of the returning sun. Levick, still concerned about his relationship with his superior, was relieved that winter had passed off with no major confrontations. He confided to his diary on 2 July: ‘On the whole we are getting on quite well together. Priestley and I are really good friends. I am, I think establishing an ascendancy over Campbell, which has been a good thing in many ways, as I am gradually getting him out of many of his fads. He is not a bad chap but hopelessly out of place as a leader, being much too self-conscious and lacking most sadly in guts.’ He added: ‘I feel rather a beast sometimes when Priestley and I get away together and crab him to each other, whilst all the time he and I remain outwardly friendly. Campbell and I have more in common to talk about on general subjects than Campbell and Priestley, and as the latter can’t stand having Campbell with him on his peregrinations, C. and I generally take our walks together, though I would rather go with Priestley. That pretty well sums up our general relations I think.’

Levick was also concerned about Dickason (‘a fine chap’), whose duties as cook confined him indoors far more than the others, and who might therefore be out of condition for the start of spring sledging. Once again Levick had his way, writing on 12 July: ‘I have after a good deal of difficulty got Campbell to arrange for Browning and Dickason to take turns over the cooking, so that now Dickason gets outside work on at least three days a week.’ Abbott was not enthusiastic about the arrangement: ‘Had a day’s cooking, relieving Dick so that he could work in the open – have just finished the business – I wouldn’t be a cook for any money.’

The following day came a bad bout of polar ennui (a medical complaint diagnosed early on in Arctic and Antarctic exploration), the first for many months thanks to Levick’s vigilant defusing of potentially inflammable situations. It started, trivially enough, with an absurd argument about the number of times Levick had trimmed coal aboard Terra Nova. Campbell evidently feeling that his status as the ship’s first mate was being impugned, got into a tremendous sulk and refused to speak to Levick. The doctor bore this for two days, but when he realised Campbell was starting to get into ‘a sort of neurasthenic condition’, he decided something must be done. When Campbell left the hut to get some exercise, he followed him out, caught him up, and tackled him.

Ironically to present-day readers, Levick went on: ‘I have given him a tonic with strychnine in it [nux vomica] and he has been better and much more cheerful ever since.’

Levick’s sensible treatment of a disagreement that had threatened to fester into a serious breach was in character. But it took some courage to lecture his superior officer, and some nerve to suggest that Campbell was marking time while he and Priestley were achieving useful and fulfilling work. On the other hand, mentioning spring sledging journeys to their leader, and promising a tonic to a man with hypochondriacal tendencies, were both masterly touches.

Levick’s return to favour suffered a set-back when they nearly fell out again over the vexed question of ventilation.20 Although Campbell vetoed Levick’s proposal to extinguish one of their two stoves, he permitted the door to be left open for longer periods, and even promised to have a small kind of cat flap made in the inner door. Perhaps the fact that he was putting lap bindings onto his skis in preparation for their forthcoming trips had put him in a good mood.

While the Northern Party were still in the grip of winter, Levick had pondered on the sledging plans master-minded by Campbell. These focused on two major journeys to the westernmost end of Robertson Bay – Cape North and Cape Wood – which Scott had been so anxious for them to explore. Levick wrote: ‘Our only chance of success in this direction, lies in making the whole journey in the spring, and in getting back before the sea ice breaks up. We must thus start in the very early spring, which is the most trying time for sledging, owing to the very low temperatures, frequent hurricanes, and short periods of daylight.’ Campbell may have been raring to go, but Levick was looking forward to this period ‘with much the same sensations that I used to feel when looking forward to exams’.

There were to be two separate sledging parties, the first consisting of Campbell, Priestley and Abbott, the second of Levick, Browning and Dickason. Levick summarised the plan of campaign thus:

Levick’s party, in other words, was to be to a large extent nothing more than a support party, ferrying supplies for the major exploration effort. He was, however, also intending to pursue his zoological researches. ‘During the summer, and the end of spring, if I get back in time, I am hoping to put in great work among the breeding penguins here, and the other birds and seals etc.’ So, ‘this is our programme, and it will be interesting to see how it develops.’ Not as planned, inevitably.

Sledging fever was upon them. On 24 July Dickason tramped out to The Sisters to get himself fit. Whiskers were shaved off, since they would become uncomfortable as their owner’s breath froze on them during hauling. Levick lectured the party on breaks and fractures, and Dickason listed a hundred and one other things to do: ‘sledges and harness, canvas “kayaks” to go with them, weighing up food, each man’s allowance per day, what clothes to wear on the march and in the sleeping bag, which is lightest and best …’

An immense amount of preparation and meticulous attention to packing went into each sledging trip – unsurprisingly, since on one of the two major journeys made by the Northern Party during the spring of 1911 the total weight hauled (including their two sledges) was 1,163lbs. All the gear had to be stowed so that it could be unloaded or reloaded in order of need and at top speed – essential on foul-weather days. The rapid provision of shelter, light and hot food, in that order, took precedence. So the tent was carried on top of the load, and the primus lamp and the stove were also ready to hand. Then the delicate scientific instruments had to be boxed up out of harm’s way, and the weight distributed evenly over the centre of the sledge. As the rations disappeared down ravenous gullets, the space released would be filled up by the same volume of geological and other specimens. Other bulky items were gallon tins of oil and the shovel and ice axes needed to erect the tent on frozen ground. Each man was also allowed to squeeze in 10lbs of spare clothing. These mighty loads were pulled by harnesses of canvas and leather – shoulder straps buckled onto a waistband, one for each man – stitched together by the deft fingers of Abbott and Browning.

Given Campbell’s orderly mind and organisational skills, the Northern Party and their laden sledges probably looked reasonably tidy as they set out each day, compared, say, with the Western Party under the leadership of Griffith Taylor. ‘Old Griff on a sledge journey’, wrote Cherry-Garrard in a delightful passage, ‘might have notebooks protruding from every pocket, and hung about his person a sundial, a prismatic compass, a sheath knife, a pair of binoculars, a geological hammer, chronometer, pedometer, camera, aneroid and other items of surveying gear, as well as his goggles and mitts.’ And, just like Lewis Carroll’s White Knight, he also carried his own lethal weapon: ‘in his hand might be an ice-axe which he used as he went along to the possible advancement of science, but the certain disorganization of his companions’.

‘The question of clothing for these spring journeys’, wrote Levick as their preparations were in full swing, ‘has been occupying us a great deal, and everyone is using his own judgement entirely in clothing himself.’ As they were to discover, the major and insoluble problem was the cumulative build-up of sweat during the march, which then froze and thawed alternately, so that after a few days the men were lying in pools of water. ‘The misery of turning out in the morning with wet clothes, into a temperature … on an average between –20° and –30°F, and sometimes colder, is no joke, and it is this that makes spring sledging what it is.’

The Northern Party’s rations owed much to those previously worked out by Shackleton for Professor David’s Magnetic Pole Party – a judicious combination of protein and carbohydrate. Pemmican – a mixture of 40% dried meat and 60% fat – decanted from dozens of frozen tins (a frightful job) and mixed with biscuits put through the mincer was the staple of their diet, supplemented by whole biscuits, cheese, raisins, sticks of chocolate, sugar, cocoa and tea. The pemmican mixture was served hot for breakfast and dinner, washed down with hot cocoa or tea. ‘Cheese at –20°F’, Levick was to note later, ‘is peculiar stuff, & cracks in your mouth like toffee, and the emergency biscuit is so hard as to require very careful worrying, and I realized then, with months of sledging before me, how lucky I am to have a magnificent set of teeth. I shall always be most particular in future, if ever I have to examine candidates for these expeditions, to see that their teeth are strong.’

Cooking was itself fraught with dangers. Writing as ‘Primus’ in the Adélie Mail, Dickason’s light-hearted account of the tribulations of a sledging cook lists the hazards: incinerating the tent, knocking over the lamp, causing the pemmican to boil over into the stove, dropping a pot of hoosh21 onto the filthy floor. He concluded: ‘I could write several paragraphs on the subject of the inconvenience due solely and simply to the low temperatures … I have not forgotten the blisters on my fingers, the result of grabbing the cooker with my bare hands.’22

Before the two major journeys outlined by Levick were undertaken, Campbell had decided on making a couple of trial runs to break in the sledgers. Campbell, Priestley and Abbott set off first, to the southern end of Robertson Bay. The Southern Cross party had made several journeys there and had warned of the perilous nature of sledging on the sea ice, due to the early and uncertain break-up of the pack. This outing, which lasted from 29 July to 4 August (several days longer than anticipated, owing to bad weather and worse surfaces), took them as far as Duke of York Island, and brought a taste of the blizzards which they could expect to descend upon them without notice. Pulling for home near Warning Glacier on the eastern side of the bay, Campbell was ‘awakened by a terrific din and found the lee skirting of the tent had lifted the heavy ice blocks we had piled on it and in another minute would have gone. I had just time to roll out of my bag, grab the skirting of the tent and shout to the others to do the same’. While he and Priestley sat on the skirting, the unfortunate Abbott had to crawl outside to pile on more ice blocks. He had much the worst of the night, climbing back into the tent sopping wet and being disturbed at regular intervals in an absurd sequence of events:

Meanwhile, Levick and his two companions remained at Cape Adare. At 11.15 a.m. on 31 July they saw the sun for the first time since the autumn. ‘There was at that time a great mirage effect all round, and bergs, sea ice, and mountains appeared jumbled about in a very queer manner … It was infinitely cheering to see it again. I took its photograph.’

They kept themselves busy. Levick set Browning and Dickason to scrubbing the hut, and himself to ‘a great feat of engineering, consisting of hewing a road through the ice boulders on the South beach, for sledges to pass on & off the sea ice. With the debris from the boulders I have made an embankment leading down in a gradual slope to the sea ice, and both cutting & embankment look most imposing.’ With their own sledging journey in sight, Browning overhauled his skis and sleeping bag, and Levick made himself a nose guard from a piece of red flannel he discovered in a case of wax matches – ‘tonight in consequence my nose is dyed a brilliant vermilion’.

On 2 August they were struck by the same blizzard that was pinning Campbell’s party into their tent. As the weather worsened, Levick went out to retrieve a lantern he had placed at the top of his new slipway to guide the others in. He soon lost his bearings in the thick drift.

As with so many others, the White Death had come close to tapping him on the shoulder.

With winds up to 100 mph and the barometer at 28.126 and still falling, it was the worst hurricane they had yet encountered. Levick was not yet anxious about the sledge party, thinking (correctly) that they had probably holed up to wait out the gale; instead he read up on Scott, Shackleton and Borchgrevink, ‘picking up as many tips as possible’. On 4 August he was sufficiently concerned to go out looking for Campbell’s group, and met them walking back, having depoted their sledge, tent and most of their gear. That night he weighed the three travellers. Campbell had lost 3lbs, Priestley 5lbs and Abbott 9¼lbs.

The first major western journey had originally been scheduled to leave on 20 August, but as with all the Northern Party’s plans – to date, and to come – this now had to be changed. They had discovered just how difficult the surface was in Robertson Bay, alternating between high pressure ridges and salt-flecked ice (the most difficult sledging surface imaginable, since the granules stuck to the sledge runners). The conclusion they had been forced to draw was that any notion of an extended journey over the sea ice was impossible: travelling was so slow that they could not carry enough provisions to last them out. ‘There is nothing like the Antarctic for sending the schemes of mice and men all to blazes,’ wrote Levick.

Campbell decided to add Dickason to his team to help with the hauling. Dickason wrote on 5 August: ‘I was informed by Mr. Campbell that I should be attached to his party for the long trip to the W., as three men was not enough to pull a loaded sledge over the bad surface, which greatly alters his plans … now us four will have to take as much as possible and get as far as we can.’

It had proved a tough introduction to sledging for Campbell and Abbott, and even for the seasoned Priestley, an experienced spring sledger from Discovery days. It cannot have done much for Levick’s pre-exam nerves, since he was to be in charge of the second trial expedition. He was relieved that Priestley had been loaned to them by Campbell ‘to show us how to look after ourselves, as none of us have had any previous experience’.

They set off on foot on 8 August, making for the depot left by the earlier party, which they would adopt for their own four-day journey. Levick found himself lumbered with some 37lbs of gear, which he carried on his shoulders, slung between two ski sticks; Browning ended up carrying his on his head; Dickason was sure his load was getting heavier with every mile. Reaching the abandoned tent and sledge at about 4 p.m., they pitched camp under Priestley’s tutorial gaze.

In essence the procedure was very like that on any field trip, with a few minor differences. The steam from the cooker froze solid to the walls of the tent, as did the sweat on their clothes and the medicinal brandy in its bottle, although their brisk post-prandial walk was made in a (relatively balmy) temperature of –15°F. Then it was time for bed. Levick removed his day clothes, all frozen stiff as boards, donned his night gear: woollen pyjamas, rabbit’s wool helmet, dry socks and finnesko,23 and snuggled down into his reindeer sleeping bag, into which he had sewn a blanket bag. No boy scout could have been more comfortable.

His enquiring mind had led him to decide that the pools of water accumulating in sleeping bags on sledging journeys was due to breath rather than sweat, and proved this to his satisfaction by sleeping with his head outside his bag, contrary to established custom. ‘I was a little nervous about it, as Priestley assured me I should lose my nose while I slept!’ In fact he did wake up in the middle of the night wondering if his nose was frostbitten; however, a quick rub reassured him that it was still there, and ‘in the morning my bag was dry inside, & so it was the next night, whilst all round my face on the outside of the bag, was a thick layer of ice from my frozen breath’.

The following day Levick was introduced to the discomforts of photography on the march – ‘whenever you touch any metal part of the camera with bare hands … you get a “burn”, the tips of my fingers being now well blistered owing to this’. Still, Warning Glacier, with its hanging wall of ice, was dazzlingly beautiful: ‘it would be profanity to attempt any description of it’. Although hauling the sledge on the return journey was as troublesome as it had been for Campbell’s party (‘the beastly thing felt as if it had about six ice anchors out’), they returned to Cape Adare in great spirits on 11 August. For them at least it had been a most satisfactory introduction to spring sledging.

The following day the party gathered around the fire by Abbott’s bunk (he was suffering painfully from rheumatism of the knee), ‘and had a very lively conversation on the chances of Capt. Scott & Amundsen getting to the Pole’. Their conclusions were somewhat bizarre: that Amundsen would have to use manual power for getting his sledges onto the Barrier ‘as the dogs will not be able to do it’ and would have to man-haul all the way to the Pole, while their four British rivals ‘will not be required to pull sledges, the extra hands doing this for them’ and should therefore win the race. ‘The final result of our consultation was that it would be a near thing. I say jolly good luck to those who get there whoever they are.’

Their revised plan suffered a further set-back on 15 August with another almighty gale; at one point during the night they feared for the safety of the hut. The next morning, ‘lo & behold! All the sea ice has gone out of the Bay, leaving just a narrow strip, from half a mile to a mile or so in width, at the very end, under Cape Adare; and in place of our usual white expanse, wavelets of black ice were beating on the ice foot.’ Dickason could hardly believe that the wind could shift ice like that – ‘it was between three and four foot thick and much thicker at the ridges, and stretching across a distance at the narrowest part of twenty miles or more’. As Levick realised, the implications were serious: ‘This was the most awful blow to our hopes of sledging along the coast, but if it had happened ten days later, Campbell, Priestley, Abbott & Dickason would certainly have been dead men, as they would have gone out on it.’

Inspecting the damage, they found that their outer wall had suffered but that their gear and provisions remained intact, while Borchgrevink’s store house had lost its roof and a 20-ton beam had been hurled 20 yards away.

Levick continued his enjoyable routine of photography and zoology: ‘Have been reading up all I can find about penguins … My great ambition now is to work them up thoroughly and write a book on them when I get back.’ Campbell meanwhile was assessing the chances of succeeding in the sledging ambitions for which he had been waiting all winter. They would now have to add on hundreds of extra miles to reach their destination, skirting right round Robertson Bay on the strip of safe ice which fringed the steep coasts. On 21 August, harking back to their original decision, he wrote gloomily: ‘Altogether the outlook made me wish more than ever that the ship had had sufficient coal to take us back to Wood Bay’ – conveniently forgetting that they themselves had decided on their present location.

Levick recorded yet another set-back on 25 August: ‘This morning on going out of the hut we found that the ice had gone out right up to the end of Cape Adare, and the open Ross Sea was beating on the edge of the narrow strip of sea ice which remains with us, extending only a few hundred yards from the edge of the beach. The noise of the breakers was distinctly audible, and a dense bank of dark “sea-smoke” was rolling away off the open water.’

It was not until 8 September that Campbell, Priestley, Abbott and Dickason finally set off. They were to be away for ten days. Dickason was clearly apprehensive: he added a note to his diary: ‘In case I should not return from this sledging trip … I entrust this log to the care of F. V. Browning who will cause it to be delivered to my mother, failing her my Brother. Address 42 Hazelhurst Rd., Lower Footing, London S.W. No letters. H Dickason.’

Levick and Browning travelled with them as far as Warning Glacier, due south of Cape Adare, to photograph and geologise for a few days, before returning to the hut on the 13th. That first night the two men camped some seven miles from Cape Adare, and were joined by Abbott, who had been sent back to the hut to retrieve his ski boots (no doubt with a flea in the ear from Campbell). Although it was –30°F, Levick recorded that they spent a convivial evening in their sleeping bags, smoking and singing shanties. ‘The atmosphere in the tiny little tent, with three pipes going and every means of ventilation lashed up tight, can be easily imagined, and we all coughed a good deal. Abbott remarked “my word, it is so thick you can hardly breathe – it’s lovely”.’ The following morning, Levick and Browning returned Abbott to his group, and set off to photograph the glacier and mountains which surrounded them. Then started three days of terrifying weather, ‘which’, admitted Levick later, ‘I remember more as a bad dream than anything else’. It started with a warning cloud over the top of the glacier. This they treated as an interesting photographic subject, but, accompanied by puffs of wind, soon started to make their way back to their tent. At first ‘it was a dignified retreat, as we stopped several times to take photographs of interesting parts of the glacier as we passed them, even up to the last moment, when our retreat had broken into a run’.

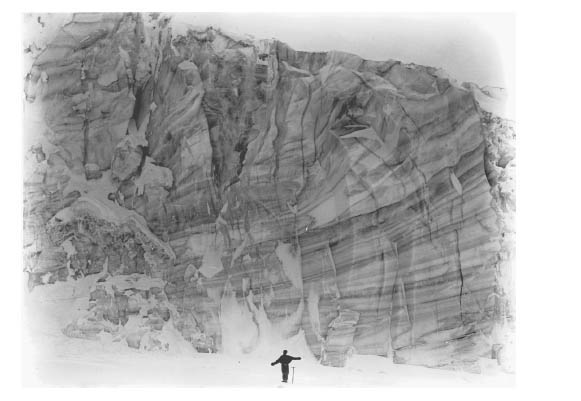

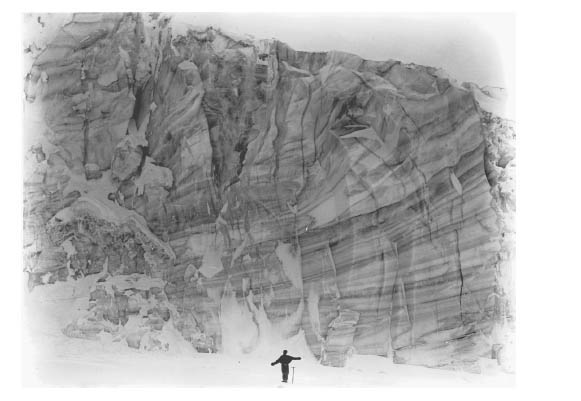

14. Given scale by the tiny figure semaphoring at its foot, the spectacular ‘marbled’ face of Warning Glacier – so named by their predecessors at Cape Adare because the clouds of drift blowing off its top was the reliable herald of a blizzard to come. Levick and Browning made many excursions there to photograph and collect geological specimens.

They decided to stay with their tent, which was impossible to shift in the gale-force winds, rather than to take their sleeping bags to the shelter of the cliff, although they kept ready to ‘make a hop for it’, as Browning euphemistically put it. Levick described the ordeal which followed:

The tone of Levick’s account might have been light-hearted, but the two men were in serious trouble. Effectively, they were quite alone, since the other four were out of reach and hearing, and most probably in equally dire straits. The cup of tea provided by Browning, that ‘most indefatigable cook and general “bucker up”’, although encrusted with reindeer hair, was as welcome as a glass of vintage champagne.

They decided to head for Cape Adare with all speed – although not before Levick had taken two more photographs for Priestley’s benefit. Exhausted and hampered by salt-flecked ice, they struggled homewards, to find the topography entirely altered:

During their dash for safety Levick had strained his leg, and Browning was suffering from some undiagnosed complaint, so they did not move far from the hut. ‘I think we both feel a little lonely,’ wrote Levick on 17 September, ‘but Browning is a cheerful companion and is working like a nigger. He is an excellent cook and lays himself out to please me with all sorts of surprises in the way of dishes. He is a Devonshire man, having spent his boyhood on a farm before he entered the Navy. He is a qualified torpedo instructor, and first class petty officer, and is certainly gifted with brains, and runs the meteorological observations exceedingly well and intelligently during Priestley’s absence.’

Meanwhile, the senior sledge party had travelled anti-clockwise round the bay past Dugdale Glacier, before curving north-west across the three bays which looped into the coast on the way to Cape North: Relay Bay, the Bay of Bergs and Providence Bay. The scenery of glaciers backed by mountains was magnificent; Priestley described it as their chief solace during the frustrating time that followed. They then pushed on past Cape Wood at the northern end of Providence Bay, only to be halted at Cape Barrow by a dangerously thin surface, to which they were alerted by the alarming noise of a seal gnawing the ice beneath their feet.

They had no choice but to retrace their steps to Relay Bay, camping in the spectacular cave at Penelope Point. Since it was a Sunday, they loosed off a volley of hymns. ‘I turned in my bag without swearing tonight,’ revealed Dickason, ‘the first time this trip, I suppose the hymns had something to do with it as I was turning in whilst singing.’ The next day they struck out for home across Robertson Bay – the ice able now to bear their weight. The two watchers at the hut spotted them approaching on 18 September, and learned over a glass of champagne that they had had no wind at all while Levick and Browning were being pounded by the blizzard 30 miles away.

A few days later Levick returned to Warning Glacier with Priestley, Browning and Dickason, to be subjected to the same wearing winds and snowstorms as before. A gale on the 25th kept them in their tent – ‘this laying up business shakes the tobacco pouch up a bit’, complained Dickason, ‘as I cannot go to sleep every time I turn in so I get the pipe under weigh [sic] and read a little’. Even so, Levick felt that the thirty photographs he had taken of the glacier made the journey well worth while. The geologist concurred, and Levick reported with modest pleasure on 2 October: ‘Priestley says that his notes and my photographs of Warning Glacier make up the most valuable piece of work we have done since we came.’ He was kept so busy that he had no time to wash any clothes, and set out as part of the support group for Campbell’s second big sledging journey on 4 October in the same things he had been wearing for the past three weeks. ‘It can’t be helped.’

Levick and Browning travelled together, for the following ten days, and as before encountered severe weather and bad surfaces while making their way across the bay to Penelope Point. They then split from the other party, and having made a trip on skis westwards to Cape Wood and photographed from afar the major landmarks that the others would encounter, they turned eastwards towards the Dugdale, Murray and Newnes Glaciers at the southern end of the bay. Levick was still suffering leg pains and his diary entries are notably less cheery than before. The pair were relieved to reach Cape Adare and the hut just before another blizzard struck on 13 October. ‘We are both as hard as nails’, crowed Levick, ‘though our noses have suffered by sun & frost!’