CHAPTER 4

Cybernetics and Organisms: Fusions

SYSTEMS AND CYBORGS

The cyborg, it must be noted, is not a singular or simple figure. To assume either of these positions is to misunderstand that figure and to neglect the nuances of its critiques and alternative articulations, or to misconstrue them. Like the notions of the human that it interacts with, the cyborg has a complex genealogy. Indeed, the label ‘cyborg’ has been used to mean various things by different commentators and at different times, in response to the numerous ways of conceiving of human-machine fusions. Problematically, however, certain understandings of the cyborg have become more commonplace than others, and consequently, we are both overfamiliar and unfamiliar with the figure overall. This is attributable largely to SF and the popularity of characters such as the Terminator and Robocop. Such characters, though, interact with pre-existing notions of cyborgs, in turn continually changing our understandings of those figures.

At a rudimentary level, a cyborg can be defined as:

A self-regulating organism that combines the natural and artificial together in one system. Cyborgs do not have to be part human, for any organism/system that mixes the evolved and the made, the living and the intimate, is technically a cyborg.1

Although this is a basic definition, and it has been problematised in various ways by various theorists, it is important to see the (hi)stories of the term ‘cyborg’. The cyborg is a portmanteau of ‘cybernetic organism’, and it thereby suggests a meeting between the biological – that is, the organic – and the mechanical. What remains open to interpretation here is how much the two components are fused in this meeting, and to what extent they may retain their distinctness even in spite of their amalgamation.

The cyborg emerged out of the cybernetics movement associated with the work of Norbert Wiener, who in the mid-twentieth century appropriated early Hellenistic ideas about governance (deriving from ‘κυβερνητικη’), and combined them with new ideas emerging in the field of computer science to form a new, transdisciplinary approach to systems.2 As Davis writes, ‘cybernetics is thus a science of control, which explains the etymological root of the term: kubernetes, the Greek word for steersman, and the source as well for our word “governor”’.3 Cybernetic systems impose order and structure on phenomena by making self-regulating feedback loops. If criteria within a system reach certain levels, then other parts of the system are designed to be responsive in order to maintain pre-set thresholds. In these systems, more routinisation and efficiency is enabled.

Typically, it is humans who are the users of such systems, and so they are figured as the eponymous steersmen that the technologies are ordered-to. What this means, though, if humans are exempt from cybernetic systems as steersmen, is that any coming together of organic and cybernetic parts is not totalised. Human discreteness and specialness therefore remain in ways that connote functional-substantive readings of imago dei, where attitudes such as dominion are emphasised.

Yet equally, the focus in cybernetics is on flows of information across systems at various levels, rather than on discrete categories. Emphasis on these information flows means that fundamental differences between categories and beings are able to be undermined; ‘cybernetics proceeds on the assumption that however man and machine may differ in construction, the process of communication and control is identical’.4 The significance of this levelling through information flows is profound, as posthumanist theorist Katherine Hayles notes:

Of all the implications that first-wave cybernetics conveyed, perhaps none was more disturbing and potentially revolutionary than the idea that the boundaries of the human subject are constructed rather than given. Conceptualising control, communication, and information as an integrated system, cybernetics radically changed how boundaries were conceived.5

Cyborgs, then, have their roots in a movement that rendered previously embedded and fixed boundaries as altogether more plastic and malleable, if not entirely mutable. This opens up the possibility of a critique of the substantive mapping of the human that has been depicted as a Venn diagram throughout this investigation.

Yet I would question to what extent cybernetics truly radically changed how boundaries were conceived, especially given that the human remains as an elevated figure in/above these systems. For Wiener, ‘the world of the future will be an ever more demanding struggle against the limitations of our intelligence’.6 This corresponds not to a struggle of distinction between humans and machines, but one of their co-existence.7 Here, it is humans who are creatively responsible in such a way that, for scholars such as Hatt, the ‘enlargement of man in the cybernetic revolution’ can help to realise imago dei.8 This has led critics such as Hayles to note that, ‘for Wiener, cybernetics was a means to extend liberal humanism, not subvert it. The point was less to show that man was a machine than to demonstrate that a machine could function like a man’.9 In other words, Wiener takes the image of man, which highlights independence, freedom, and control,10 as his starting point.

For Davis, this principle in cybernetics conveys a Gnostic attitude,11 where humans are regarded as ‘strangers in a strange land’.12 This might on the one hand refer to how information liberates us from given structures and norms insofar as technologies, concordant with human nature, are allowing us to express that human nature in expansive ways unconstrained by corporeality or genetics. On the other hand, given that humans are not fully incorporated within cybernetic systems but remain the steersmen, there are grounds to argue that humans are strangers in a strange land of their own making.

To expand on this, in systems of increasing complexity, where different parts such as organisms and cybernetics (technologies) are brought together in hybrid assemblages, control over categorical distinctions becomes ever more difficult to maintain. Bruno Latour writes at length on this:

When we find ourselves invaded by frozen embryos, expert systems, digital machines, sensor-equipped robots, hybrid corn, data banks, psychotropic drugs, whales outfitted with radar sounding devices, gene synthesisers, audience analysers, and so on, when our daily newspapers display all these monsters on page after page, and when none of these chimera can be properly on the object side or on the subject side, or even in between, something has to be done […] It is as if there were no longer enough judges and critics to partition the hybrids. The purification system has become as clogged as our judicial system.13

While Latour notes the numerous hybrid beings that now proliferate in our world as a result of the widespread application of cybernetics,14 he also astutely notes that we continue to seek to impose order on them, by reabsorbing them into binarised categories such as subject and object.15 This suggests tensions within cybernetic systems between fusions and categorical separations that place strain on our models, or what Latour terms our clogged purification and judicial systems.

In my reading, these systems are clogged because of the (hi)stories that reveal them to us and that shape our attitudes to them. These stories encourage a dichotomised outlook where we seek freedom and control; we seek fusions and yet also discreteness. Although cybernetics opens new possibilities for circumventing substantive categories by introducing the fluid flow of information as a key concept, those categories ultimately remain intact because cybernetics emerges from the same humanocentric attitudes that preceded it.16 Indeed, the only boundaries that Wiener seems most comfortable to redraw are the ones that concern human knowledge, where it is our curiosity that impels us to push back these frontiers.17 This predicament connotes that of the evolutionary posthuman and transhuman, where the generation of the ‘other’ was used to vindicate the identity of the self.18 In both cases, the human seeks to control the threat of the mixed and to mark its own sense of discreteness and difference, yet as Latour notes, the classification system (which I have identified as being part of a substantive approach) is strained and unsustainable. An alternative way of figuring it is needed.

ASTRONAUTIC CYBORGS

Unsurprisingly, the substantive view remains prevalent even when cybernetic technologies that represent fusions are applied to human bodies and selves, as later developments in cyborg (hi)stories reveals. The first use of the term ‘cyborg’ to describe a human located within the technologically augmented, cybernetic systems was in astronautics. The cyborg was originally proposed by Manfred Clynes and Nathan Kline as a means of sending man (the gendered subject)19 into space by technologically augmenting his body. In Clynes and Kline's own words,

The purpose of the Cyborg, as well as his own homeostatic systems, is to provide an organisational system in which such robot-like problems are taken care of automatically and unconsciously, leaving man free to explore, to create, to think, and to feel.20

What is important to note here is that, although there is a physical fusion of man and machine in this notion of the cyborg, there remains a sense of distinction in that the machinic elements supplant workings of the body that are already regarded as robot-like. Cognitive elements become the seat of humanness and are involved in the drive to expansion, while the more blatantly machinic ‘organisational system’ takes care of the mundane things that are already automated in the body insofar as we do not need to exercise regular conscious thought over them.

Effectively, Clynes and Kline engage with a divided and Cartesian view of the human, where technologies are incorporated into the body and not the abstract sense of self which is cognitive.21 The incomplete sense of fusion that this signifies closely adheres to what I identify as an evolutionary posthumanist logic of cybernetics, where the human remains distinct from the system of fusions as a kind of steersman. Hayles writes of this tension of cyborgs: ‘the linguistic splice that created it (cyb/org) metonymically points toward the simultaneous collaboration and displacement of new/old, even as it instantiates this same dynamic’.22 This dynamic is one of continuity and discontinuity, of sameness and difference, where the binary parts dialectically encircle one another in an endless loop. Although the cyborg here, like the evolutionary posthuman of the previous chapter, presents a way of mediating and resolving these tensions, in its cybernetic and astronautic forms, it is absorbed into such dichotomisations.

To elucidate, the cyborgian technologies are either taken as ‘specifically an amplifier of human beings’,23 indicating sameness; or, on ‘the insidious side of the cybernetic equation, […] the human individual [risks being] merely a momentary whirlpool within larger systems of information flow; thus the steersman himself is subject to control’,24 which suggests a difference between humans and technologies. These attitudes strongly lend themselves to an uncritical embracing of or caution about technology as a general category. Common to both, then, is a substantive understanding of humans and technologies that either homogenises fusions under a human label, or rejects them in favour of an a-technological human nature. Neither of these positions enable us to fully address the hybrid beings that Latour discusses because our concern remains caught up with the welfare, discreteness and specialness of the human rather than its relationships with and responsibilities to others.

The astronautic cyborgs that Clynes and Kline present suggest sameness even where enhancements are made to human abilities: nothing is lost, and humanness is thereby sustained.25 The issue here is that such a vision of humanness is predicated on the idealised human subject, which has been typically defined by excluding others on the basis of sexism, racism, classism, heteronormativity and, more broadly, anthropocentrism.26 The cyborg theoretically offers a way of circumventing these issues by rethinking the separation of human and machine. This would call into question the ontological priority of ‘the (ideal) human’ as I am advocating, but such questioning is muted in Clynes and Kline's work in favour of an expansionist reading of technologies.27

On this point, the astronautic cyborg resonates with the transhuman and human, and this resonance can be extended to include how both figures are interpreted theologically. As Daniel Dinello writes:

Originally imagined to adapt the body for space travel and fulfil divine aspirations of reaching the heavens, the cyborg also reflects the religious desire for godlike perfection, immortality, and – as a weapons system – omnipotence.28

The context of space is significant here, because it represents a transcending of the earth and a literal and conceptual elevation of the human spirit.29 For Haraway, who is deeply critical of this position, this means that ‘the cyborg is also the awful apocalyptic telos of the “West's” escalating dominations of abstract individuation, an ultimate self untied at last from all dependency, a man in space’.30 The Gnostic vision of ‘strangers in a strange land’ is realised and fulfilled in this view, which Haraway parallels with Eden in terms of the escapism that they promote. Such escapism emerges from an ontological prioritisation of the human reflected in (first-wave) cybernetics and in astronautic cyborgs, where ‘space is not about “man's” origins on earth but about “his” future, the two key allochronic times of salvation history’.31 These places (that Haraway deems ‘allotopic’)32 fuel our humanocentric attitudes to technology, while overlooking our obligations to others closer to home, on earth.33 This underwrites the need to reinvestigate our (hi)stories in order to articulate a more responsible ethic that does not make prior assumptions about humans, natures and technologies.

To briefly reflect, the human seen primarily as central, but also as outwards-looking, knowledge-thirsty and ever-expansive, is firmly embedded in Clynes and Kline's astronautic cyborg. The way that the cyborgian technologies are figured in the astronaut's body without impinging on one's humanness suggests that our humanness is locatable in our minds, or at least in our passion and drive to further ourselves. As such, the cyborg is here assimilated to the human;34 cyborgian prosthetics and technologies are no more or less a part of our essential and cognitive selves than our clothes are.35 Parts can be changed,36 replaced, even upgraded, and yet the human remains human by virtue of an idealised, largely pristine and discernibly human consciousness. This reveals a set of narratives that reflect and guide our attitudes to technologies and self-conceptions. On this point, the physical form of cyborgian technologies is not enough to consider by itself, but the guiding principles and designs behind the technologies, indicative of larger attitudes to humans and technology, are crucial. Clynes and Kline's early conceptualisation of the cyborg evinces the evolutionary posthumanist and transhumanist tendency to leave certain tenets about the human largely intact. As with cybernetic systems, this allows for difference in spite of physical fusions, which might be surprising given that Clynes and Kline's cyborgs directly apply to the human body. Conceptually, however, these fusions are downplayed in favour of an affirmation of the substantive human.

‘HEALTHY’ CYBORGS

Moving from Clynes and Kline's emphasis on space travel and exploration in their transhuman cyborgs, the question next shifts to one about cyborgs closer to home and rooted firmly in the quotidian. The significance of the space setting, for Clynes and Kline, manifested in how the cyborg systems were designed and integrated into the body so that ‘man’ could explore a world beyond himself, in the pursuit of some form of transcendence. How does this translate on earth, though? What is there for the cyborg systems to enhance, improve, or transcend?

Finn Bowring muses on this:

What is desired by the cyborg enthusiasts is, in effect, the elimination or revision of those features of human existence which, being censored, repressed, harmed and alienated by modern social conditions, lead to disempowerment, frustration and suffering. The elimination of our capacity to suffer is not, however, a satisfactory answer to suffering – or at least not a human one.37

The cyborgian, transhumanist desire to transcend the human (although not in as complete a way as some claim,38 particularly in terms of the organic/machinic distinction that largely remains) is here, according to Bowring, mapped onto the deficiencies that we find within ourselves under social conditions.39 Although the context is notably different to astronautic cyborgs, it seems that the undergirding attitudes remain somewhat similar in terms of an attempt to improve, or rework a part of what it is to be human via a rigorous application of technologies.

The most common cyborgs that we experience on an everyday basis, though, are not technologically enhanced superheroes (or villains for that matter), as various comic series and SF works would have us believe,40 but rather they emerge from surgical theatres, hospital wards and even various clinics globally.41 These ‘cyborgs’ have any number of prostheses, ranging from contact lenses, to surgical scars, to pacemakers and transplanted organs.42 To what extent have these technologies changed the human?43 For Elaine Graham, ‘technology has moved from being an instrument or tool in the hands of human agents, or even a means to transform the natural environment, and has become a series of processes or interventions capable of reshaping human ontology’.44 This connotes Bowring's concern cited above that the ends, the teloi, of such cyborg amendments and augmentations are not in themselves human and perhaps thereby embody an element of fear and technophobia.

For Bowring:

Because the elimination of the human's capacity to suffer would mean the creation of a post-human being, the goal and beneficiary of this solution cannot be humanity itself. The need for the cyborg, in other words, is not a human need, a need whose satisfaction would reaffirm the essence of humanity. It is, rather a technological imperative, for the true purpose of the re-engineering of the human being is the abolition of the obstacles presented by people to the reproduction of machines.45

Bowring here perpetuates the organic/machinic distinction that was tacit in Clynes and Kline's transhuman cyborgs. As part of this, qualities of humanness are exclusively projected on to the organic side of the distinction, rendering machines as enemies of humans, and as a threat to the whole human enterprise. It seems that cyborgs far less remote than in space are too close to home for many, and the promise of fantastic cyborgian technologies becomes overshadowed by concerns over the status and the sovereignty of the human. Putting this in cybernetic terms, we find ourselves asking: are humans still the steersmen of these technologies; are humans still in control?46

Against this fear, though, there are strong ethical reasons for the employment of cyborg technologies on medical grounds, and theology can be, indeed it has been, an important contributor to these discussions. Where technology is accepted under medical grounds, in particular by theology, it is largely with a strict emphasis on therapy. For Lutheran theologian Ted Peters:

God has promised an eschatological transformation, the advent of the new creation. Our task this side of the new creation is to engage in the much more modest work of transformation in order to improve human health and flourishing.47

Peters advocates a future-oriented ethic, which he terms a ‘proleptic ethic’, that advocates a modest human participation, including technologies, in a larger eschatological schema. We are not trying to do God's work or efface him with our technologies, then, which is traceable in visions such as Bacon's to realise a New Jerusalem or utopia on earth.48 Rather, health and flourishing are the goals that Peters espouses. In this regard, ‘instead of thinking of cyborg brains as transhuman, we could think of them simply as fabulously human’.49 Health and humanness parallel one another in Peters' work, suggesting a normative view of both, into which cyborgs seem to be absorbed.

What is fraught in notions of medical cyborgs is the idea and ideal of ‘health’: it is a desirable state that we are in seemingly perpetual pursuit of. The trouble with the concept, particularly relevant to a discussion of cyborgs, though, is that technologies are constantly shifting the baseline of what we recognise as ‘healthiness’. Is health about having a fully functional body and mind in accordance with the model of how humans were originally made in God's image, in an originary Garden? Or is health about finding ways to improve that original design by using, for example, neural implants to enhance cognitive functioning? These questions expose, in a theological framework, ambiguous attitudes to technologies in a medical sense where ‘health’ can be taken to mean either ‘therapy’, associated with a reparative objective; or ‘enhancement’, associated with an evolutionary and developmental (even transhumanist) objective. Briefly, ‘therapy’ is about returning to a state of healthiness; ‘enhancement’ is about going beyond that state to improve upon it.

Common to both principles is an assumption about health as a normative state that is sought or that is improved upon: Peters' proleptic ethic, for example, ‘begins with a vision, a vision of the perfected human being residing in a new creation’.50 Although the setting is new, the vision cannot help but draw on previous narratives and (hi)stories, and so even a forward-looking ethic such as a proleptic one must involve a degree of looking back to Edenic models of human creation, perfection and perfectibility.

Here, the human as able-bodied is upheld, and cyborgian medical technologies can reinforce such norms by restoring ‘lacking’ conditions in the form of laser eye surgery, cochlear implants, prosthetic limbs and so on.51 The issue here is that, like all normative-based attitudes, certain users will be excluded; here on the basis of disability insofar as it is perceived as a lack in dominant ‘ableist’ attitudes, and something to be technologically corrected. Dan Goodley and Katherine Runswick-Cole note this: ‘many disabled people have been denied the opportunity to occupy the position of the modernist humanist subject: bounded, rational, capable, responsible and competent’.52 Alternatively, through a critical investigation of norms offered by the notion of the ‘dis/human’, which has much in common with the critical post/human, the stability, homogeneity and totalisation of such norms is undercut. Disability is thereby not figured as a lack against an able human self – in origin or telos – but is instead an opportunity to reflect on ways of rethinking normativity, in particular beyond ableist notions of health.53 Cyborgian prosthetics, such as those worn by Aimee Mullins in her creative collaborations with Alexander McQueen, as well as bioart from performers such as Stelarc and Orlan, can critique and subvert human norms by challenging the schism of replacement/enhancement, and instead use technologies to gesture towards alternative aesthetics expressions of the body.54 To be sure, Goodley and Runswick-Cole are more pragmatic and recognise that some norms are valued and to be left in place,55 but they nonetheless recognise that ‘becoming dis/human does not offer a prescriptive opposite to the conception of the norm, rather it works away at a norm that is always, and only can be, in flux’.56

This flux, in my estimation, relates to tensions between health as therapy and as enhancement that underline concerns about iatric technologies. These technologies are open to both interpretations, and they thus complicate our understandings of what it is to be both ‘normal’ and ‘healthy’. For Andy Miah, however, who theorises much on transhumanism, the question of therapy and enhancement in medicine is a trivial matter:

Medical technology is not able to support transhumanist ideals precisely because it normalises technology, bringing it under the humanist guise of therapy. In contrast, the requirement of the transhumanist is to make sense of these technologies as transcending humanism, as becoming something beyond humanness (not nonhuman, but posthuman).57

While I agree with Miah in part, noting the normalising tendency applied to medical cyborgs, I would dispute his identification of transhumanism as fully transcending humanism. I have demonstrated in the previous section that the transhuman draws out certain humanistic notions and attitudes, rather than transcending and surpassing the human entirely. Contrary to Miah's comments, I contend that transhumanism essentially normalises technology in the same way that humanism does, albeit by using technology to go beyond foundational norms of health in pursuit of new norms and ideals (such as Clynes and Kline's model of the astronautic cyborg to venture into space).

From this, we can see how the cyborgs explored thus far assimilate into, and thereby affirm, our structured notions of health, therapy and enhancement. Common to these cyborg iterations is a reluctance to lose sight of the human steersman at the helm of technological developments and fusions. Eugene Thacker characterises this particularly well in discussing transhumanism. For Thacker, the transhuman:

[…] necessitates an ontological separation between human and machine. It needs this segregation in order to guarantee the agency of human subjects in determining their own future and in using new technologies to attain that future.58

Pithily, Thacker underscores how the steersman is preserved, which is a trend reflected in all kinds of medical cyborgian fusions, contrary to Miah's argument of a difference between the two. There is a conceptual difference maintained between the human and the machine, even in spite of physical fusions.

With medical cyborgs, the fusions may be more commonplace and more intensive than those envisaged of early astronautic cyborgs, and they may be more permanent. They may extend even to that sacred and neurological seat of the self, but concerns about the human are commonly allayed by the sustenance of an ontological difference, out of which the human is preserved and is able to maintain at least a degree of ‘control’. Physically, then, the human body may undergo alterations, amendments and augmentations, yet conceptually, for Clynes and Kline's designs and for medical cyborgs, the human remains intact.

SF CYBORGS

In a world replete with images and representations, whom can we not see or grasp, and what are the consequences of such selective blindness?59

There seems to be something of a reluctance to fully accept mixity in all of these discussions of the cyborg that have been considered thus far. In part, this can be accounted for by popular culture, where, to reiterate, (generally limited) portrayals of cyborgs alongside those in the ‘real world’ inevitably impact our broader understandings of that figure. The images that we commonly have through SF tend to sensationalise and ‘other’ the cyborg in a manner akin to the evolutionary posthuman discussed in the previous chapter. Typically, this leads to an ‘anxiety in popular culture that robotic and technological implants or enhancements not only turn us into something other than ourselves but also put us under the control of outside agents’.60 Of course, there are examples of less hostile depictions of cyborgs in SF,61 but they are nonetheless portrayed as distinct from the human in one way or another.

To be sure, cyborgs are associated with fusions of organic and cybernetic parts, and this is reflected in SF, but through the narratives, a sense of separation is overall maintained. In Star Trek, for example, the ‘Borg’ amalgamate (and thereby fuse) genetic data from different species and incorporate it within their own species identity. On that point, however, they are portrayed as a sinister alien race that threatens to subsume humans on board the Enterprise, thus revealing their essential and antagonistic otherness. Similarly, in the Terminator films, Arnold Schwarzenegger's hyper-masculine character, although eventually coming to demonstrate more humanistic traits over the series, is consistently referred to as ‘other’ to the human, often leading to mildly comic scenes of misunderstandings and miscommunications. Even films that are adaptations of early modern fictions, or that draw more prominently on historical tropes and ideas, have a tendency to other the cyborgian as the menacingly not-quite-human.62

Some films raise deeper questions about human-machine identities and differences. In Spielberg's A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), for example, arguably a derivative of Shelley's infamous Frankenstein story, the main character, David, becomes the lens through which we are brought to critically consider the exclusivist and destructive tendencies of humans. David, who is also a contemporary techno-Pinocchio, is the robot who dreams of becoming a real boy, but humans reject him and his kind, seeking to destroy them in carnival-esque ‘flesh fairs’. Ironically, humans concomitantly live out hyper-technologised lives in dystopian cyber-cities. Similarly, Ex Machina (2015) subverts the Turing test that is used to determine whether a robot manifests human-like intelligence. In the standard test, if a machine, unseen by a human conversing with it, can convince the conversant that it is human, then it has ‘passed’ the test. In the film, though, even when visual cues are reintroduced, the differences cannot be fully ascertained, leading the human protagonist to doubt his own humanness and the criteria that he uses to measure the humanness of others. In these ‘techno-mirrors’, we are encouraged to ask: who is more human(e)? Who is (more) cyborg?63

Although SF may seem to raise such important questions as these, there is also a sense in which those questions are distilled and allayed by the technologies that convey them. Expressing this notion, renowned media theorist Marshall McLuhan wrote 50 years ago that ‘the medium is the message’.64 Here, McLuhan emphasises, in what was at the time a novel theory, that attention needs to be given not only to the content of media transmissions, but also to the form of the media technologies themselves. We are arguably distanced from any of the cyborgs on the screen, even the most humanoid and humane ones, because ‘nothing impedes the subtle integration of human, natural, and artificial systems more than the present crudity of our technological interfaces – whether keyboard, screen, data suit, or visor’.65 The implication here is that technological devices that we associate with cyborgisation are ironically too clunky to lead us to accept that we are cyborgs. In other words, as with cyborgs in space or in hospital beds, we do not find a convincing account of fusion between organism and machine as the label ‘cyborg’ implies. In this sense, media technologies may depict certain fabulated images and mediate the imaginary to us, but they also maintain a strong sense of distance by sustaining the conceptual space between virtual and actual.

Indeed, as esteemed SF writer and theorist Margaret Atwood notes, this distancing may even be a crucial ploy in maintaining the appeal of SF: ‘Perhaps, by imagining scientists and then letting them do their worst within the boundaries of our fictions, we hope to keep the real ones sane.’66 The element of distance surrounding us from SF functions here as a sort of safety valve, as a sort of magic mirror where we can act out our deepest nightmares so that we do not allow ourselves to let them become reality. (Can the same be said of our fantasies? How do we distinguish them, in some cases, from our nightmares?) It is this distinction, between virtual and actual that operates across the screen, that allows us the perspective of the allegedly detached. We are the spectators of these SF scenarios and, as spectators, we are chiefly observing, rather than being drawn into the drama.

McLuhan's views are now arguably dated, though, and may not correspond fully to the complexities of the technologies that we engage with. Maintaining McLuhan's emphasis on the media technologies themselves, given the pervasiveness of these technologies in everyday life (such as smartphones, ‘intelligent software’, or the internet more generally),67 the screen may no longer be sufficient as a clear divider. Jean Baudrillard develops McLuhan's theories here with a more contemporary, postmodern focus by emphasising the ‘ecstasy of communication’. According to this theory, our engagements with technologies are so immersive that ‘there is no more discrete subject as the distinctions between the real and the medium dissolve’.68 Through Baudrillard's work that reinterprets many of McLuhan's key principles, we realise that when we are watching cyborg images in SF, we are engaging both with the images or content, and also with the technology that presents them. This is cyborgian; yet, as with other iterations of the cyborg explored thus far, common parlance does not concede such fusions, and we remain decisively ‘human’.

There is, however, a key difference between McLuhan and Baudrillard's work on media technologies and the human that needs to be noted. For McLuhan, media technologies are prosthetic ‘extensions of [the hu]man’,69 which emphasises how the human is central to technological augmentation, in a similar way to how other cyborgs in this chapter have established a technological layer upon the foundational human subject. For Baudrillard, though, media technologies are ‘expulsions of man’70 in a process of transference of our identities to the machine. McLuhan's cyborg-like beings, annexed through prostheses, are based on a principle of augmentation; Baudrillard's on one of self-loss that may parallel SF narratives of humans succumbing to machines (consider here The Matrix, or RoboCop). What do we gain from either perspective, though? Is it better to see technologies as able to perfect the human, or is it better to fear them? What is the human at the centre of these questions?

I contend that the last question is the most overlooked, and yet is also the most important one in our relationships and engagements with technologies. Pushing beyond a celebrating or fearing of technologies allows us to reflect on questions about our self-understandings, our place in the world, as well as our ethical models that enmesh other species and beings. SF is equipped to deal with such questions, but only if audiences ensure that they are open to the reflection and interrogation of themselves that these stories demand. As media theorist Scott Bukatman notes, ‘SF frequently posits a reconception of the human and the ability to interface with the new terminal experience.’71 The ‘terminal identity’ experienced here is ‘an unmistakably doubled articulation in which we find both the end of the subject and a new subjectivity constructed at the computer station or television screen’.72 It suggests a more complex interaction of human and technological than either McLuhan or Baudrillard develop. The human, we find, is deconstructed rather than affirmed and/or transcended,73 and this marks a new, interrogative way – beyond that of humanocentric cybernetics – in which we can be considered cyborgs.

Bukatman figures cyborgs in this way by placing emphasis on both media technologies and the narratives that they convey, whereas McLuhan and Baudrillard give arguably greater weight to the technologies, and other SF commentators have focused more exclusively on the content. For Bukatman, there is a crucial narrative dimension not only to the content of SF but also to the media technologies.74 To illustrate this, Bukatman notes how ‘the illusion of subject empowerment depends upon the invisibility of the apparatus’.75 By highlighting this, Bukatman is able to deconstruct and critically investigate the complex relations at play between humans and technology, and between content and form. SF presents a powerful way through which to develop this deconstructive methodology because it recognises and reflects parts of our own culture while engaging in practices of fabulation by using alternative worlds and technologies to scrutinise our own. To be sure, Bukatman does not downplay the power struggles of subjects (i.e., tensions between self and ‘other’) as part of this bricolage of narratives, but he seeks to displace and refigure those subjects and their struggles by decentralising them.76 This is the groundwork for an alternative figuration of the cyborg that is particularly significant for the work of Donna Haraway and for theology, which I begin to elaborate in the next chapter.

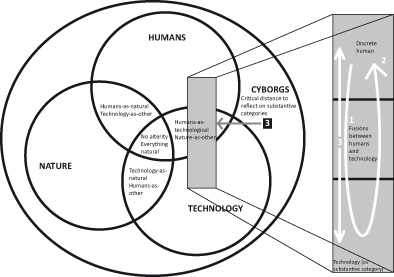

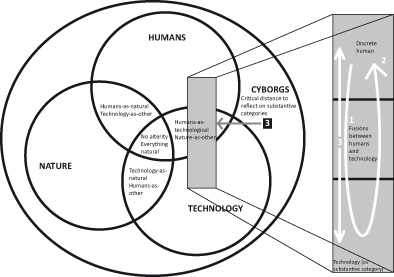

FIGURE 4.1 Venn diagram to show human–technology dynamics in different expressions and understandings of cyborg figures

We then have, from Bukatman's work on SF, a new conceptualisation of the cyborg, and with it, potentially a new way of conceptualising – or at least interrogating – the human. Cyborgs from their inception, as Figure 4.1 depicts, have explored fusions of technological and non-technological phenomena (1), yet such fusions are never totalised or complete insofar as the discrete human remains (2). This means that overlaps across categories are shifting and contestable zones that generate anxieties. Evidencing these, Major Motoko Kusanagi of Mamoru Oshii's anime sci-fi Ghost in the Shell (1995) declares, ‘I guess cyborgs like myself have a tendency to be paranoid about our origins.’ Cyborgs have multiple origins weaved in complex (hi)stories, including cybernetics and sci-fi. Notions of the human are embedded here, and these resonate with ideas discernible in Edenic anthropologies. While reflection on these (hi)stories is useful, when we seek to ‘fix’ or remedy our ontological anxieties by reabsorbing the contestable zones into pure categories that are easier to understand, manipulate and control, we continue to espouse a humanocentric ordering of the world. SF narratives can challenge this by allowing us to establish a critical reflective positioning alongside our technologies at the same time that we closely engage with them as audiences (and participants) in those narratives (3). This demands a new way of considering closeness and distance that takes us beyond the more simplistic models of early cyborgs that are predicated on a central, foundational human subject. I take this complex connectivity with technologies expressed in SF as the starting point for a way to usefully begin to rethink how we see ourselves in relation to technologies in ways that do not prefigure the (ideal) human through practices of exclusion.