4

Dances with Death

What could you do, back in the 1920s, if you had a plane to spare, loved flying and extreme thrills, and wanted to earn a living at the same time? The answer is you could barnstorm. After the First World War a glut of aircraft came on to the market at bargain-basement prices. The US military was trying to offload a lot of the Curtiss JN-4 biplanes, known as Jennys, which had taken part in the conflict and were now surplus to requirements. Costing over $5,000 new, a Jenny could sometimes be found on sale for as little as $200. A good number of military pilots who had become expert at flying the Jennys in battle were now keen to snap up the planes for their own civilian use. Plenty more low-cost planes, some of whose designs were ahead of their time, were also going cheap as their manufacturers went bust, due to the fact that the civil aviation industry hadn’t mushroomed as quickly as some had hoped.

During the early 1920s, there were hundreds of talented American pilots who were prepared to fly their planes anywhere, and do whatever they could to make money. Some delivered mail; a few carried more illicit cargo, such as carrying whiskey across the Mexican border. But of all the flying activities, barnstorming was the most popular and profitable for those prepared to take the risks. It was encouraged too by the lack of federal regulations on aviation, which allowed all kinds of crazy stunts to be indulged in, without much thought to the safety of those either in the air or on the ground.

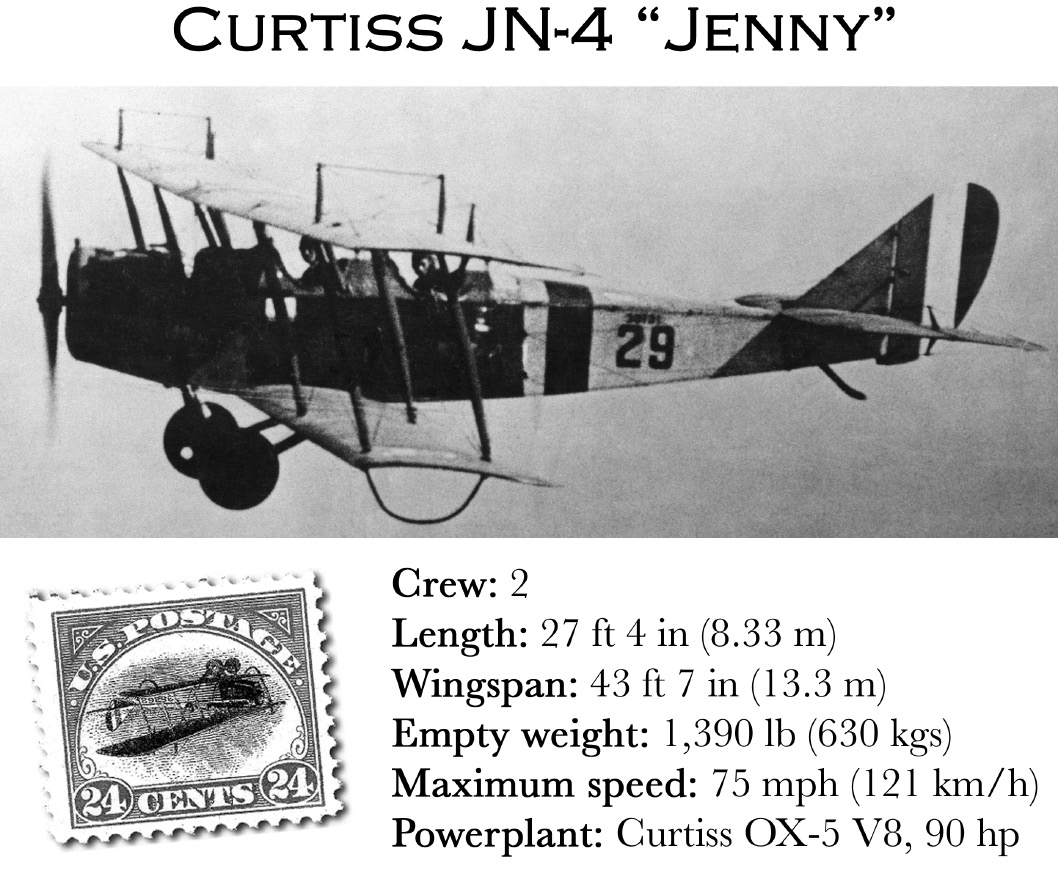

10 The Curtiss JN-4 (‘Jenny’).

Many young fliers who had returned home to America from Europe after the First World War took up a drifter lifestyle, drifting from town to town across America, offering rides for money, meals, or gasoline, and sleeping out in fields under the wings of their planes. They had to be jacks of all trades, including self-taught engineers, because no one else was around to fix their machines if they broke down or needed spare parts.

Aircraft were still a comparative novelty in those days and, especially in rural areas where there was plenty of space to fly in and few other attractions, people came in droves to watch the latest hair-raising aerobatic display. Not surprisingly, the most successful barnstormers were the ones who put on the most spectacular shows and, just as importantly, had a talented promoter working alongside them to pull in the crowds. One such star of the barnstorming era was Ormer Leslie (‘Lock’) Locklear.

Born to be wild

Born in 1891, one of ten children, Locklear spent most of his early life in Fort Worth, Texas, and got a grounding in carpentry, his dad’s profession. Even as a school kid, though, it was obvious he had far too much adrenaline for a quiet life of woodworking and construction. He proved he had a devil-may-care attitude towards his personal safety by doing wild stunts on his bicycle – pedalling furiously up a plank ramp onto a barn roof and then leaping off, Evel Knievel style, onto a platform below. His passion for aviation started when he saw his first planes.

Early in 1911, a team of international fliers, mostly French, had been putting on aerial displays in nearby Dallas. A group of businessmen persuaded them to travel the thirty miles or so to Fort Worth. For the two days of their show, stores closed, schools announced half-day holidays, and cheap streetcar rides were offered to the site of the big event. Ormer Locklear and some of his friends were among the 15,000-strong crowd that looked on, dazzled by the exhibition of piloting skills. In that same year, the pioneer flier Calbraith Rodgers landed at Fort Worth to fix a clogged fuel line during the first transcontinental flight across North America. Locklear was again watching, this time on the Hattie Street Bridge with his brothers.

Not having access to a powered aircraft, but inspired by what they had seen, the Locklear boys built a glider with fifteen-foot wings from bamboo fishing poles and shellacked linen. They pulled this behind a car so that it rose up to 150 feet in the air, each brother taking a turn at flying the fragile craft back to the ground, guiding it the only way they could – by shifting their body weight from side to side. In search of further thrills, Locklear graduated to a two-cylinder Indian motorbike and sped around his neighbourhood, popping wheelies and even standing on his head while steering the machine. On one occasion he shot across a busy street in downtown Fort Worth and ended up plunging through the doors of a saloon.

News of his exploits started to get around. The famous magician and escape artist Harry Houdini learned of them when he came to Fort Worth and did a series of shows at the Majestic Theatre. One day he struck up a conversation with Locklear’s younger brother in the sporting-goods store where he worked. Houdini reasoned there might be some good publicity to be had by teaming up with this local stunt kid, and was completely sold on the idea when he met the charismatic and good-looking Ormer – a crowd-pleaser if ever there was one.

The great escapologist proposed that Locklear drag him, hog-tied, behind his motorcycle down Main Street in Fort Worth. While hurtling down the road, with wide-eyed spectators lining the way, he would break out of his bonds and roll free. The young man, not usually averse to risk, wasn’t keen on the idea but Houdini won him round by insisting that he would take every precaution so as not to be injured. He chose Main Street because it was the only one in town that was paved, if wooden posts set into the ground to protect horses’ hooves counted as paving. To protect his body and legs he would wear thick, quilted overalls and have a hood round his head.

Locklear agreed, and the next day sat astride his bike while Houdini had his hands tied behind his back by volunteers and then lay down in the street. Revving his machine Locklear rolled forward, taking up the slack on the rope that was knotted around Houdini’s ankles, before opening the throttle and roaring away. Evidently, the stunt was a success because the magician went on to play the rest of his scheduled shows in Fort Worth – to packed audiences.

In the air at last

In April 1917 the United States entered the First World War and on 25 October of that year, a few days short of Locklear’s twenty-sixth birthday, he enlisted in the Army Air Service. To celebrate, he planned to ride his bike on the wall around the top of a new building in Fort Worth and, the night before, set up platforms so that he could take the corners more easily. He told the press of his intentions, and a few hundred locals gathered the next day to watch him. His plans were stymied at the last moment, however, because of a complaint by the Humane Society.

Any disappointment on Locklear’s part, though, was quickly forgotten. After ground training at the Texas School of Military Aeronautics he was assigned, with the rank of second lieutenant, to Barron Field near Fort Worth to finish his flight training, and now finally he got his hands on a real-life gasoline-powered aircraft. He flew a Canadian version of the Curtiss Jenny, with a ninety-horsepower engine and a top speed of ninety miles per hour, and right from the start he showed his true colours.

Flying seemed to come as easily to him as breathing, and before long, fearless as ever, he would occasionally clamber out of his pilot’s seat onto the wing or over the cowling, thousands of feet above the ground. The first time he did this was during a test in which the aim was to read ten words on the ground while flying at 5,000 feet. No one had ever achieved a perfect score because the plane’s lower wing always got in the way. Locklear’s solution was to climb onto the wing and look down in front of it while his instructor kept the aircraft on an even keel. He got all the words right – and everyone else who tried to copy his trick afterwards was reprimanded for their trouble.

On another occasion, Locklear was in the front seat of the Jenny when a radiator cap worked its way loose causing hot water to spray in his face. He climbed out of his seat, inching forward over the fuselage until he could reach the cap on the exposed engine and screw it back on. Dangling radiator caps, loose spark-plug wires – whatever it happened to be – the young flier thought nothing of unbuckling his safety belt and sorting out the problem right on the spot, in mid-air.

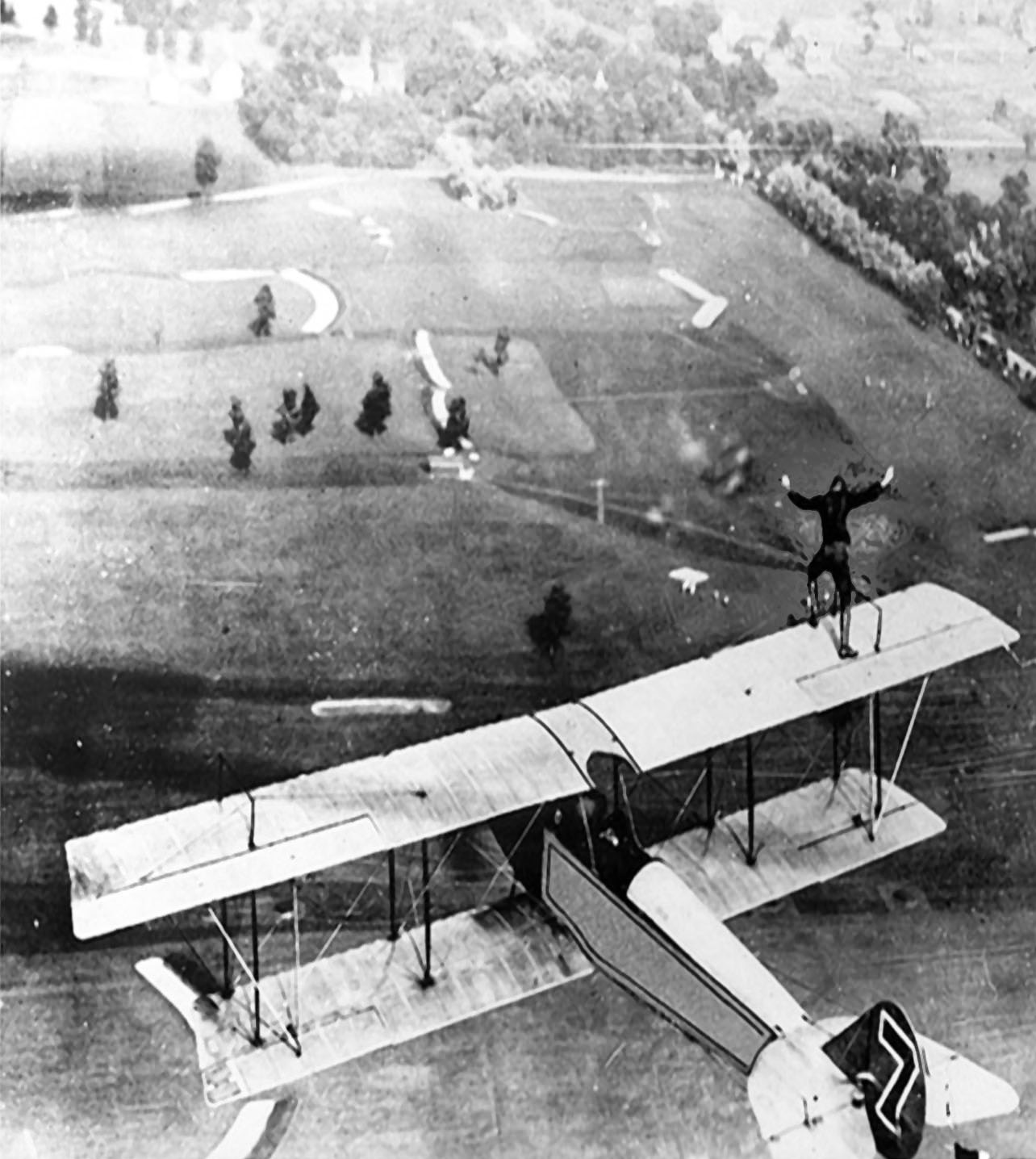

Ormer Locklear may not have been the first person ever to do ‘wing walking’ but he was the first to make a regular habit of it and, eventually, to turn it into a lucrative profession. One day he set out to prove his superiors wrong in their belief that no extra weight could be put onto the leading edge of an aircraft’s wing without seriously disrupting the plane’s aerodynamics. With a student at the controls, Locklear crawled out of his cockpit onto the Jenny’s lower wing and made his way to stand on the leading edge. Lo and behold, nothing untoward happened – an important discovery, from the military point of view, because it showed that guns could be safely mounted on the front of a wing away from the fuselage.

11 Ormer Locklear ‘wing walking’, c.1919.

Pretty soon, Locklear and a couple of like-minded friends, Milton ‘Skeets’ Elliot and James Frew, were doing aerial stunts on a regular basis whenever they got the chance. Word reached the commanding officer of Barron Field, Colonel Thomas Turner, and he went out to see the three men in action. Taking the smart option, instead of dressing down the reprobates he invited them to put on official demonstrations to show off the agility and stability of the Jenny. Their piloting skills led to their remaining at Barron Field as instructors instead of being shipped out to fight in France where, if they had survived, they would probably have become among the top aces of the war.

Not surprisingly, given that their stunting was now officially sanctioned, Locklear and his buddies pushed their luck to the limit. On 8 November 1918, Locklear made history by transferring between planes in mid-air, dropping from the undercarriage of Frew’s plane onto the wing of Elliot’s, which was flying directly below. Within months he had perfected a different kind of plane-to-plane transfer that was even riskier.

King of the wing walkers

Before leaving the Army Air Service in May 1919, Locklear met William Pickens, an experienced press agent who had already been successful in promoting Lincoln Beachey and some other outstanding young fliers. Locklear, Skeets Elliot, and another stunt-flying instructor from Barron Field, Shirley Short, signed a contract with Pickens to appear in aerobatic shows around the country. Within a few months, Locklear had achieved national and international fame as the ‘King of the Wing Walkers’.

The skills he had honed while wing walking for a serious purpose in the military, he now put before the public for entertainment. Together with Elliot and Short, he developed new tricks, including various ways of hanging from the lower wing by a rope ladder or trapeze bar, or, on the upper wing, performing handstands. It so happened that the Curtiss Jenny came as standard with over-wing struts that served ideally as braces for wing walking, although spectators who had never seen them before often assumed they had been added specially for doing stunts.

Of all Locklear’s aerial antics, none was more impressive and dangerous than his ‘Dance of Death’ – a manoeuvre so incredibly risky that it has never been attempted since. It involved Locklear flying one plane while Elliot flew another, right alongside, so that the wings of the two aircraft were almost touching. On a signal, the two pilots would lock their controls in place, climb out of their cockpits, scamper along the wings – passing each other along the way – and then hop into the cockpit of the other plane. Such audacity and breathtaking skill drew in huge crowds, thanks also to the deft handling of the media by Pickens. Soon Locklear grew wealthy from his escapades, earning up to $3,000 a day – the equivalent of about $50,000 today. This was in stark contrast to the hand-to-mouth existence of most barnstormers. But even Locklear, aerial megastar that he was, continually had to dream up new ideas and madcap exploits to keep his public interested.

It wasn’t long after Locklear became a global celebrity that Hollywood took an interest in him. One of his aerobatic displays in Los Angeles caught the attention of the movie-making community and was followed by a number of well-publicized exhibitions at an airfield owned by Sydney Chaplin, brother of the famous comic actor. In no time, Pickens had arranged for Locklear to appear as a stuntman in Universal’s film The Great Air Robbery (1919). During the shooting, in July 1919, Locklear made the first successful transfer between a moving plane and a speeding automobile below. In a later shot he did one of his trademark plane-to-plane hops, before rounding off his first venture into Hollywood escapism with another plane-to-car switch, in which he dropped into a car to wrestle with a villain before grabbing onto the undercarriage of the plane just feet above him and climbing away to safety, moments before the car flipped over and crashed in a ball of flames.

Falling star

Shortly after Locklear arrived in Hollywood, he met the vivacious young actress Viola Dana. At twenty-three she was already the star of dozens of films stretching back to her childhood, and was Buster Keaton’s off-screen leading lady. Locklear and Viola began a very public romance, becoming one of the celebrity couples of the time. They even, according to local press reports, became engaged, despite the fact that Locklear already had a wife, Ruby, from whom he was separated, living back in Texas. Viola worked at Metro Pictures (which later became part of MGM), and her high-flying lover would often buzz her on the Metro lot in his Jenny, sometimes ricocheting off the roof of a soundstage where he thought she might be filming.

In December 1919, while awaiting the premiere of The Great Air Robbery, Locklear and his flying partners put on a series of aerial shows in California. One in San Francisco, on the 19th, was a benefit performance – and for this Locklear pulled out all the stops. Hanging one-handed from a skid, he waved to the crowd while the plane flew so low that onlookers could see him grinning. Then he clambered onto the upper wing, made his way to the tip, and posed while balanced on the ball of one foot.

Soon Locklear was basking in the glow of Hollywood glamour, surrounded by titans of the industry such as Cecil B. DeMille (an aviation enthusiast himself and owner of an airfield), Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and Rudolph Valentino. In April 1920, the William Fox Studio (now Twentieth Century Fox) signed him to star in The Skywayman, on a wage of $1,650 a week, alongside the Australian movie queen Louise Lovely. As the title suggests, the film revolved around furious aerial-action sequences. There were two plane-to-plane transfers: one done by Skeets Elliot and a second by Locklear himself. This was followed by a gunfight in which Locklear perched on the landing gear of a plane in flight, while the crooks raced away in their car.

The movie’s climax involved a night-time action scene over an oilfield, which the director had wanted to shoot during the day and then darken with the help of filters, or use miniatures instead. But Locklear insisted on doing the whole thing live, and at night. Other pilots were successfully copying his stunts and coming up with new ones, and he wanted to prove that he was still ahead of the game. So, against the advice of the studio, on 2 August, the very last day of filming, he persuaded Elliot and Short to do the night-time shoot.

Searchlights lit up the skies above an oilfield next to DeMille Airfield. The plan was for the lights to illuminate the plane carrying Locklear and his pilot Elliot as it made a spiralling dive of more than 4,500 feet towards the oil derricks, then to switch off at the last minute to allow the plane to level off. Tragically, the lights stayed on, blinding Elliot and causing him to smash into a pool of oil next to the well, and the plane to erupt in a fireball. Both men died instantly. Somewhat gruesomely, Fox included the crash and its aftermath in the final release, together with a closing scene – shot earlier – in which Locklear and Elliot are seen walking safely away from the accident. Among those watching the horrific events of the night unfold was Viola Dana, who afterwards refused to fly for more than a quarter of a century.

Locklear’s funeral ceremonies – two of them, in Los Angeles and Fort Worth – would have been worthy of the greatest of movie icons. Thousands of fans gathered outside the funeral home where the aviator’s glamorous girlfriend wept over his coffin. In Texas, his estranged wife did the same, before Locklear and Elliot were both buried in their hometown. Years later, in The Great Waldo Pepper (1975), which Robert Redford directed and starred in, the life story of the main character was loosely based on that of Locklear. At its premiere, one of the honoured guests was Viola Dana.