Chapter One

RUE DU LAC

If I believe in anything, I believe this: Life is no chunk of cheese. Ask any guy over forty and he’ll tell you the same thing. Life is a goddamn feast. Everything that comes before is just a burger, the basics—a place to live, a job, a ball game on TV, getting laid. But crawl over that forty-yard line and, brother, that burger is just so much ground chuck. At a certain point, you want the finer things. If I didn’t, I’d still be stumbling around the kitchen in that cottage back in Connecticut, cutting out coupons. At least, that’s the conclusion I’d reached during an interminable flight to Milan. Alitalia had booked me in a seat next to the window, and as the plane banked over Mont Blanc, I attempted to zero in on the things that mattered to me now.

How, you might ask, did I wind up in this spot? Last seen, I was cooking for some friends in my kitchen back home; next thing I know I’m on a plane bound for Italy. It hadn’t taken much to set things in motion. The more I thought about it, a getaway sounded like the perfect tonic for the frustrations of midlife—my midlife, that is, a scene out of The Heartbreak Kid. Three or four months of barnstorming through Europe, working in fabulous kitchens, cooking alongside master chefs—at first, it seemed crazy, a fantasy run wild. I’d been dreaming about just such an adventure for a long time. Suddenly, it made perfect sense. The time was right; something told me it was now or never. Yes, I wanted to learn how to cook, but that well-made goal came wrapped in the more fundamental pursuit of a spiritual, soul-nourishing antidote to modern living. The previous few years had been a nightmare. Yet, I’d survived and managed to reinvent my life. So a trip through European cooking schools would be less an avenue of escape than an exploration—of life, of new opportunities, of misplaced passions and desires.

The pursuit of passion. It sounded like an Esquire article: what it is, how to get it, what to do with it once you have it. Most men my age are still obsessed with these questions. They’re still searching for the things that make life special—something extra, something more. Guys I know pursue countless flaky obsessions—a single-engine Cessna, a kitschy tattoo, that twenty-four-year-old trophy wife. Many of us today have the luxury and disposable income to pursue fantasies in ways our fathers never could. Somehow, with everything else falling apart around me, the one passion I was still sure of was cooking.

I love making food. It makes me happy, gives me pleasure, provides a source of creativity. The pull of the stove is very hard to resist. The urge to express myself, to prepare a great-tasting dish, is as good as it gets, and when all goes according to plan, I get as turned on as a teenager. Twenty years ago, a guy admitting that might have been treated as a crackpot. But somewhere along the way, cooking became a cool pursuit. Perhaps a culinary adventure would help me sort out my situation.

My Alitalia seatmate, however, didn’t see it that way. Discreetly, I had tried it out on Dan, a Fiat distributor on his way to Turin, who was convinced that European cooking schools were Interpol’s version of the Witness Protection Program.

“Where do you think they’ve stashed Ratko Mladic?” he asked, glancing up from a paperback page-turner. “Put a guy like that in a restaurant kitchen and no one’d ever find him.”

Omens are powerful mojo. Any person in his right mind would have regarded this nutjob as a sign from the gods and hopped the next flight back to the States. In the event that wasn’t incentive enough, the throbbing in my hand should have convinced me. Two days before leaving home, I had broken a fall, along with two small bones in my right—chopping, dicing, and slicing—hand, which had swollen to the size of a papaya, making cooking lessons all but absurd. A cast was out of the question. Between a truckload of luggage and essential kitchen paraphernalia, my limbs were already mortgaged to the hilt. Determined to flout the Fates, I paid no heed to either omen; instead, I thanked my seatmate for his insight, even shook his hand.

Nothing short of Armageddon was going to derail my adventure. In slightly under a month, working feverishly, I had managed to knit together an impressive itinerary that would take me from northern Italy through France and back to Italy for a nightcap. There were eighteen cooking schools where I could do what is called a stage, or internship, to learn basic skills from the masters, eighteen glorious kitchens in which to exercise my fantasies without fear that a fillet of fossilized cod would reach an unsuspecting dinner guest. It would be instructive beyond my dreams. Besides, I was going to have the time of my life, according to my friend Sandy D’Amato, who owned the restaurant Sanford in Milwaukee and happened to be one of America’s finest chefs. “Cooking schools are the new Club Meds,” he told me, during a break in the advance work. “Imagine the kinds of characters you’re going to meet along the way, not to mention a fair amount of horny single women.” Visions of Gauguin in Tahiti danced in my brain, quickly marginalized by the cold light of kitchen galleys presided over by stoop-shouldered women with mustaches better than my own. And anyway, I had finally talked Carolyn into joining me.

She seemed reluctant, at first. Her exact words, I believe, were: “You must be out of your mind.” The kind of trip I proposed, she said, was for dreamers and dilettantes, but in any case not her sort of fantasy. There were other issues, as well: She hadn’t spoken to me in more than two weeks, she hated to cook, and the prospect of spending three months on the road with me—and, god forbid, sharing a room with me—unsettled her. We fenced for days without resolving anything. Finally, in an effort to avoid a real confrontation, she ran off to Nantucket, hiding out there with friends until, ostensibly, I’d left the country.

Hurt by our inability to compromise, I was unprepared for Carolyn’s call in the days just before departure.

“I’m coming with you!” she cried, through the eddy of cell-phone static. I gingerly withheld a response, in case I’d mistaken what she had said. Yawn coming. Itch you? Oncoming witch ewe. Was my ear playing tricks on me? One thing was clear: The surface of her armor had cracked. I heard elation in place of her usual careful reserve.

A weight fell off my chest.

She’d just needed time to come to her senses. “I’ve been turning it over for days and realized this was the trip of a lifetime,” Carolyn said. “If I didn’t go, I’d probably regret it forever.” And? “Think about it: It’ll be just the two of us. Our own private world. Exactly what we’ve needed.”

Taxiing toward the Milan Malpensa terminal, I reflected on her excitement that afternoon, and mine. I could only imagine what it must have taken for Carolyn to arrive at that decision. Nothing, other than loneliness, came easily to her. Somehow I seemed to have breached security, and it must have unnerved her. The exposure made her unstable, as unpredictable as the weather.

In the interim, she had spent many days at the beach poring over maps, tracing our route for the next three months. On paper the trip seemed idyllic: a train ride over the Alps from Milan to Lyon, then farther into Burgundy, rural Provence, Nice, Bordeaux, Paris, and Cannes in succession before pushing back south into Italy. The details made her head spin. “I’ll never be able to pack in time,” she sighed. “But you go ahead. Do some cooking, get your feet wet, and I’ll meet you in Nice.”

Something else hung in the air, and it took some effort to pry it out of her. I can’t…. Just forget it…. Really, never mind…. Carolyn’s giggle was a smokescreen. After some exaggerated hedging, she broke like a dam. “I just got off the phone with my mother,” she confessed, “who, believe it or not, encouraged me to go with you. She only had one worry. She said, ‘Now don’t you two run off and get married while you’re in Europe.’”

So my hopes were high about Carolyn, but I was already missing the other woman in my life, the one who liked my food. Lily and I had endured separations before, when I’d traveled for work. Now it was happening again—only, this time, it would be for a few months. Through plenty of tears, we agreed to stay in constant touch. Ever loyal, she said she couldn’t wait to try my new recipes.

The itinerary had fallen neatly into place. As I sorted through websites devoted to culinary instruction, the loose fabric of a cooking-school circuit materialized in some of the most exotic locales in Western Europe. There were dozens of programs to choose from—one type in which you take classes with a group of like-minded enthusiasts; other classes I could arrange with great teachers in their homes. Using contacts I’d made as a magazine writer, I also set up some private sessions with master chefs at fabulous restaurants such as Arpège in Paris and Moulin de Mougins near Nice. I’ve been drooling over websites promoting a riot of cuisines, fabulously seductive menus. “Join us for five fun-filled days of cooking deep inside Provence….” “Our 18th Century farmhouse nestled in an olive grove provides a superbly-equipped kitchen….” “Authentic regional cooking developed and handed down over generations set in a restored Tuscan villa….” “Top chefs.” “Hands-on, one-on-one instruction with a Michelin-starred virtuoso….” “Cook with confidence and passion for your family and friends….” “Once back home, you will be able to reproduce what you’ve learned here with ease and style….”

The accompanying pictures bordered on the obscene. Plump little flans shuddered on antique saucers, casseroles burbled like Vesuvius, mussels oozed enough butter to clog the Alaska pipeline. One woman, her face surrendered in ecstasy, lowered a fat, juicy spear of asparagus into her mouth with a finesse that would have impressed Marilyn Chambers. This was Internet porn at its finest.

The come-ons and delicacies made it difficult to choose; everything was bathed in a soft-focus splendor. Many programs showcased groups of attractive, well-tanned couples holding wine glasses aloft on some candlelit terrace. Or at a picnic feast spread out in tall grass, awash in summer light that would move a poet to tears. A link whisked me unexpectedly to a cliffside retreat above Mykonos, where the dolmades looked like stubby Cuban cigars. With so much variety, how could I expect to limit a culinary odyssey to any one segment of the globe? I wanted it all and decided to hopscotch around Western Europe, hitting one fabulous school after another.

My approach was unorthodox, I knew. There are other ways to learn to cook. I could have stayed in one place and taken one long course, from basic to advanced, but I wanted to experience the best. I wanted to tap into the imaginations of great chefs. I knew my plan could get crazy. I’d risk running into some strange situations; some duds; some flamboyant, tetchy personalities—they were chefs, after all. When it worked, though, it could be amazing, life-changing. Who could use that more than I?

“Stick to France and Italy,” Sandy D’Amato had suggested. “The twin pillars of Western cuisine.”

That sounded a bit parochial coming from a world-class chef. I argued for stops in Spain, Greece, and Portugal, to say nothing of Japan, China, and India, where exotic spices challenged even the most experienced cooks. “You can’t jump-start a lamb kabob without curry,” I said.

“That may be so,” retorted Sandy, “but there has to be some focus to the cooking. Start with the basics. The French and Italians both have a grand cuisine and a peasant cuisine, unlike the rest of Europe, where there is only generic cooking. Their fundamentals of building flavors are similar, their lifestyles are complementary and intertwined. Moreover, their chefs share intimate relationships—and rivalries—that date back generations.”

The Italians, I learned, claimed credit for the prominence of French cuisine. Legend has it that Catherine de Medici, a figure of wide influence, brought her cooks and pastry chef from Florence to the court of Henri II on the presumption that the food in France was undistinguished, if not entirely inedible. As French kitchens began filling with such Florentine delicacies as butter and truffles, Catherine’s subjects had no choice but to embrace her haute cuisine. Which is why many Italians, to this day, believe that the French are basically eating Italian food.

No way was I wading into those bloody waters, but the aspects that were interchangeable in their cooking were intriguing as hell. Even after all the years at the cutting board, I could not tell the difference between a mirepoix and its ancestral soffritto, necessitating guidance to keep me from fouling up yet another ragoût (or, as the case may be, a ragú. I had never been sure).

France and Italy: I had been infatuated with both countries since childhood, cherished them as an adult. There wasn’t a custom, aside from maybe hairy female armpits, that didn’t enchant me. In the last two decades, I had never let a year pass without making a pilgrimage of some sort, whether it was holiday travel or a mad weekend of restaurant bingeing. My French was decent enough, I suppose. In preparation for the trip, I’d picked up an audio course that promised to make me fluent in Italian after just thirty days—and it might work at that, as long as the chefs limited their conversation to sentences like “Buon giorno, Carlo. It is a beautiful afternoon. What time does the bus depart for Livorno?” No matter, we’d find some way to communicate. In the meantime, I was memorizing such key words and phrases as: salt, extra-virgin olive oil, tourniquet, and resuscitator.

It has been my long-held belief that everything to be found in France and Italy is more intense and romantic than in any place else I know or care about. Of course, I am not entirely alone in this opinion. A great many people have said the same thing, perhaps in more expressive ways. People-watching from a seat in any French or Italian outdoor café is like theater; everyone has a surround of chic or clangor that is impossible to ignore. The food there is richer, more delicious, more alive on your tongue. Wildflowers seem more vivid, their musky essence as intoxicating as a highball. If you happen to stumble there, you feel more foolish than you would in, say, London, and if you soar, you fly higher than anywhere else. In the same respect, there is no place on earth where passions are more in play, which means that heartbreak, when it happens, is crueler and more tragic than one had imagined possible.

I was betting that France and Italy would work their magic on Carolyn and cast a golden spell over our relationship. So it seemed pointless or masochistic to take the train over the Alps alone. That little detour had been designed specifically as an aphrodisiac to put Carolyn in the mood. Without her, those breathtaking views would be nothing more than mountains and trees. So I cashed in my ticket for a seat on the next puddle-jumper out of Milan and arrived in Lyon before nightfall.

There was nothing coincidental about the gateway to my adventure. Most towns where cooking schools are located have some pivotal tie to cuisine: a three-star restaurant, a market, an indigenous crop, an Eiffel Tower. But only Lyon claims to be the capital of French gastronomy. The surrounding hillsides are simply infested with places to eat—a handful of groundbreaking restaurants and first-rate bistros, as well as the local version of down-home country-cookin’ joints, the bouchons that serve platters of transcendent Lyonnais specialties so buttery rich they could stop a man’s heart before dessert arrives.

Then, of course, there is Paul Bocuse. Word had it that the so-called Chef of the Century was rarely at his place down the road anymore, although it still dished up the most inspired food this side of the equator. I’d once had dinner with him in New York, and he was such a gnarly old bastard that I swore I’d never put another forkful of his food in my mouth. Then, again, I took a similar kind of oath when George W. was elected president and I hadn’t yet moved to that cliffside shack in Tierra del Fuego. I wondered if a table chez Bocuse was to be had. If a quenelles mousseline or tête de veau bourgeoise can only be savored as they were meant to be in his restaurant, then I was going to have to swallow my pride and book a seat right away.

Bocuse gave Lyon a guru. And two of France’s best-known wine-growing regions—Beaujolais to the north and the Côtes du Rhône to the south, both only a stone’s throw away—gave the city their blessing. There wasn’t a reason for anyone interested in food—serious food, that is—to set a big toe even a silly millimeter beyond the town line. The outdoor market stretched on for what seemed like miles, jammed with people picking through stalls of picture-perfect vegetables; fat saucissons; chickens the size of newborn babies roasting to perfection on the spit; mounds of wrinkly, sun-cured olives; cheeses I’d never heard of; to say nothing of the huge variety of local specialties that will never make it to the next region, much less to a Stop & Shop.

Lyon’s legacy of cooking was as old as its Roman heritage, which was still alive on the banks of the two great navigable rivers that run through the city. In 43 BC, Caesar ordered the city built where the Rhône and the Saône converged like an hourglass full of energy and bountiful light. Calling it Lugdunum, he invested it with the kind of practical Roman foresight that inspired rapid development: functional roads, a series of aqueducts and bridges, and an amphitheater where lions presumably dined as well as the emperors.

The sense of antiquity in Lyon is evident in and around the rivers, especially at night, when the castles, palaces, and cathedrals cast glowing reflections on the water’s slatelike surface. The romance and beauty of the nightscape are a magnet for crowds who promenade along the riverbanks with a formality that evokes the city’s glorious past. Saturday night, when I arrived and set out for a walk, the footpaths seethed with well-dressed couples making a slow, ceremonial procession. It resembled the set of a Merchant-Ivory film, and I supposed, with a little imagination, this was how Paris might have looked in the thirties, before the commotion of lights and technology arrived.

The next morning, I made a beeline for Old Lyon, the medieval quartier on the western bank of the Saône, preserved as it was when Agrippa designated it the starting point of the principal Roman roads throughout Gaul. I had been here twice before, dreaming of it often in the intervening years. Everything was exactly as I’d remembered: quaint and enchanted. I felt my spirits rise. The natural contours of the quartier made it seem almost miniature in scale, restricted by the backdrop of Fouvière hill, a steep cliff looming like unfinished sculpture above the terraced, rose-colored buildings. Beneath its expanse was a patchwork of narrow, brick-lined streets stacked one just above the other, running headlong into wide squares before snaking off again like those blasted concourses in modern airline terminals. Because of the tight, boxed-in façades, the streets surrendered to a current of ever-changing shadows reminding me of those early monster films when Rodan or Mothra flew overhead. But when the sun began to rise over the towers of modern Lyon, a brilliant glare blew away the cobwebs with blinding indifference.

On Sundays, the quartier slept late under a blanket of shade. It was a sultry August morning, already uncomfortable. Restaurants were shuttered until well past ten, the streets all but deserted. A brigade of scruffy cats patrolled the gutters in pursuit of scraps, while overhead a column of pigeons stood sentry on the lips of awnings, waiting their turn.

I had arranged to meet an acquaintance for brunch in the Rue St.-Jean, just around the corner from the Gothic cathedral. There were still a few hours before I was due to leave for Burgundy, where my first cooking instruction was situated, and a Lyonnais meal seemed the best way to fill the time.

David was like most expatriates who’d hitchhiked through Europe after college and had never gotten around to returning home. There was some long, sad story about a tyrannical father that I wasn’t prepared to hear. In the interim, he had carved out a new identity that owed nothing to his family—or to his country, for that matter. Tall and shaggy-haired, he had even lost the well-upholstered gloss that characterized other young American tourists, who now regarded him dismissively as if he were another baffling Frenchman.

Living practically hand-to-mouth in Lyon, David got by teaching English in a local university, and, as befits most instructors of a certain age and self-esteem, he had fallen for one of his students.

Lucy was the kind of French girl I’d idealized from boyhood: slim, high-breasted, sensual, and supremely confident, showing enough bare midriff to warrant the warning: This belly was specially reformatted to fit your television screen. The daughter of a local line cook, she was bursting with schoolgirl ripeness, a quality made evident by David’s lickerish stare; I could tell that she was amused by him but that it would soon grow old. At least her English was good; David had done his job well.

“Bocuse is shit, a turd,” Lucy said when I suggested a place to eat. “He couldn’t cook his way out of une papillote.”

“A paper bag,” David corrected her.

“Yes, exactly. That’s what I said.”

Lucy had her heart set on a bistro in Old Lyon where she predicted the breakfast would deliver an unforgettable experience. “We’ll have huitres and white wine and then something larger from the sea.”

David looked ashen. “I couldn’t put that in my mouth right now, Luce,” he said, checking his watch, which read slightly past ten. “How about later?”

“But it’s the perfect breakfast,” she insisted, her mouth drawn into a spoiled pout. “I bet Bob is more adventurous.”

Actually, oysters sounded heavenly no matter what the hour. There were few things able to make my saliva run at the very mention of a name. “But it’s August,” I sighed, “and about eighty-five degrees already. How about if we just swallow Drano instead?”

“What can be the matter? Ah, you Americans are such—how do you say?—chats.”

That could have gone either way. My money was on pussies, but David let it slide. He’s picking his battles, I thought admiringly, as Lucy led us around the corner like a streetwalker with two excited johns.

The restaurant was a typical Lyonnais boîte, the kind that revels in funky organ meat but serves a selection of tamer dishes for the tourists, with a small bar and five or six banquettes grouped below a mural of the Champs Elysées. The painting was yellow from smoke and hideously old-fashioned, but it didn’t matter, because no one other than the owner’s family ever sat indoors. We parked ourselves at one of the sidewalk tables just off the curb and waited while a blank-faced waiter took his sweet time rearranging the rows of chairs. We might as well have been invisible. There was no one else at the place, but his routine had been disturbed by our early arrival, for which the penalty was to be ignored.

I was starving. I had last eaten during the flight from New York, not counting a midnight raid on the hotel mini-bar, which I’d plundered in an effort to stanch my hunger. Over and above that (and being fairly exhausted), I felt an awful need for something satisfying, something simple and honest and unforgettable, to inaugurate my cooking odyssey. That is, if the waiter ever made an effort to acknowledge us.

“Bouge ton boule,” Lucy muttered under her breath, her eyes downcast and expressionless, as though she were talking to herself.

I looked at David, who grinned before translating. Literally, bouge ton boule means “move your ass.” But the proper phrase, according to him, should have been bouge tes fesses. “You see, in America,” David explained, “you have one ass. But the French—superior beings that they are—have two asses: a left ass and a right ass. So the only way you can properly express this is by using the plural, tes.” Even so, Lucy assured us, bouge ton boule was a much hipper way of putting it.

In due time, the waiter dragged his fesses, both of them, over to our table, propping a blackboard on one of the empty chairs. The daily special was cabillaud en papillote, cod wrapped in parchment, which sounded promising if reasonably safe. David ordered for the three of us, careful to include an appetizer that would keep his girlfriend happy.

As Lucy slurped down a dozen Belon oysters, we could only shrug with admiration. She had her own enviable technique, grabbing each slippery mollusk between the tips of her tiny Chiclet teeth, pulling gently, and then wrapping her tongue around it in a circular extracting motion. That girl was part gull, I decided. Or something else altogether.

As if reading my mind, David said, “I’m telling you, man, you ought to spend some serious time in Lyon. Aside from the tourists who swarm the streets on the weekends, there is plenty here to keep you entertained. Lucy’s got a killer group of friends. Take it from me, it could change your life.”

Watching Lucy’s kitten face dip childishly into the plate, an incentive of that sort couldn’t have been farther from my mind. She was an appealing girl, no doubt about that, but she had nothing on Carolyn, who had a gilded cameo quality about her that cheapened Lucy’s youth. And her friends had the appeal of a rice cake. I was careful not to let this show; the last thing I wanted was to hurt anyone’s feelings. Instead, I thanked David for the invitation and tried to explain why lingering in one place would be impossible for a while.

That first morning in France I was filled with expectation, but there had been times, I had to admit, when such an offer would have made me sweat. The temptation to disappear into another country, to reinvent myself, was powerful, especially at night when insecurity lurked in the shadows. Heart racing, I’d convince myself that the situations in my life, every last one of them, were completely and utterly hopeless. When that happened, all I could think about was the sudden freefall of my bank account, the screws turning in my never-ending divorce action, editors pounding on my door demanding that long-overdue manuscript, the failure of Carolyn to commit herself to my heart—every horrific responsibility and obligation pulsed through my body until only the prospect of flight from it all invited the refuge of sleep. I’d lock the door behind me and get on a plane, with only a change of clothes and that battered copy of Trollope’s The Way We Live Now to keep me entertained. There were always sirens like Lucy in those scenarios. And endless dinner parties in fabulous villas.

It occurred to me that perhaps the dream had gained some kind of purchase on my life, with cooking schools pinch-hitting for that elusive gold ring.

“I don’t know, man,” David said, as our plates of food arrived. “It sounds to me like you could stand a little fun. All those lessons are just gonna wire you in a different way. Really, how long is it going to be before you want to escape from those as well? Two weeks? Four? Listen, any time you get fed up with it, you can always come back here and crash on my couch.”

I felt sorry but said nothing to David, who seemed to sense what I’d gone through and was eager to help. But he had his own sorrows to contend with, and they clouded his judgment. He assumed we were brothers-in-arms, refugees from some train wreck of a life that needed a fresh start in a fresh place with a fresh set of dreams. He assumed that a young, saucy woman would cure all my ills. But he’d gotten me wrong. I wasn’t running away from my past, or even my heart, for that matter. I wanted to cook, but I wanted Carolyn with me, too.

“You know,” he said, with a sudden change of voice, “this might turn out to be an instructive meal for you. Hopefully, it’ll give you something to measure other meals against. Lyonnais cooking is a cut above the stuff you’re going to eat in other parts of France, like the cassoulets in Bordeaux that are so typical.”

He couldn’t have meant the lunch set in front of us. It was beautifully prepared, but unlike anything that usually came out of a Lyonnais kitchen. The papillote, for one thing, was aluminum foil rather than parchment, and the vegetables were straight from a Middle Eastern garden—a delicious sort of chickpea relish with roasted peppers and whole garlic cloves swimming in a cumin-infused olive oil. I began to peel away the fine layer of skin attached to the fish, but David and Lucy wolfed it down, skin and all. The French consume everything: eyes, knuckles, toes, the works. I half-expected them to eat the foil as well, but they either missed it or left it behind.

“This makes up for that awful airplane food you had,” Lucy said, looking approvingly at my empty plate.

The fish, as I had thought, was sufficiently satisfying, and the pastis we drank with it proved a cure-all for my blahs. A slice of very young Comté, the ubiquitous French hard cheese, acted like a stimulant on my tongue. I could feel my body coming to life again.

We talked until almost three, discussing my cooking-school odyssey in a vein that was as lively and refreshing as the rosé we were mainlining. Time was marked off by the waiter’s dagger stare. I could tell that beneath their veil of interest, David and Lucy surely thought I was tilting at windmills.

“You’re the embodiment of the galloping gourmet,” David said, struggling to swallow a smile. “With apologies to Graham Kerr, of course.”

“Maybe afterward,” said Lucy, “you can do something about the food chez Bocuse.”

We laughed easily, as the waiter delivered the check with an emphatic flourish. Several itchy looks passed between my friends. They were relieved when I covered it with my credit card.

“You must come back here and cook for us after you have had your instruction,” Lucy went on. “We will be very interested to see what you have learned. It is not often a ville like Lyon receives a chef who has trained in so many important kitchens. It will be a great treat for us.”

It took me a moment to realize she was poking fun at me. But, all things considered, I probably deserved it. In a place such as Lyon, a cooking apprenticeship was like entering the priesthood. I had to be careful not to take this thing too seriously.

“You can count on it,” I assured her. “Six months from now, I’m going to make you the best chili cheese dog you’ve ever tasted.”

On a warm Sunday evening at dusk, there are two types of people lurking in Lyon’s Place Bellecour: the honors class from the local mugger’s college—and their intended victims. I had the distinction of resembling the poster boy for the latter as I crept into the shadowy square dragging an overstuffed suitcase and a shoulder bag with a shiny new laptop peeking through the top. The instructions I’d been given were explicit; my liaison from the Robert Ash Cookery School would meet me by the statue of Louis XIV, a massive equestrian bronze depicting the Sun King in splendid battle attire.

When I arrived, the square was eerily deserted. From the comfort of my couch at home, it had seemed that the guidebooks must be exaggerating its grandeur as one of the best people-watching spots in France; now, the magnificent emptiness of Bellecour had a stomach-lurching power that caught me by surprise. It was indeed a beautiful site, surrounded on three sides by fortresslike buildings with classical façades. Underfoot, a coral-colored gravel carpet gave the square a ruddy warmth. The statue was located on a tiered platform, near the entrance to the subway. From its steps, I could keep a nervous eye out for the predators.

The first hour passed without incident. It was actually dark and peaceful. From where I stood, facing the city, the view across the river shattered any sense of antiquity. Modern Lyon was posed against the dying sky like Oz, its thousands of lights flickering in distant windows. But it was a calming radiance, unlike the restless neon skyline over cities—the City—back home. There was no loud soundtrack, no throbbing pulse, aside from the faint shuffling of gravel in the immediate vicinity. Nothing to worry about, though, as couples were merely cutting across the square like ghosts in the dark, on their way to and from neighborhood bistros.

The only dicey moment arose later, when a scrofulous-looking man in jeans and sneakers stepped out of the shadows and stumbled toward me. He had hair like a worn-out Brillo pad and the kind of bushy eyebrows that could have been mistaken for large furry insects. I stood perfectly still, my hand tightening around the shoulder-bag handle, mind racing in several directions at once, like any respectable victim. In the ensuing panic, I nearly missed his saying my name. “Hope you haven’t been waiting long,” he apologized, reaching for my suitcase.

I shot out an arm to stop him but recovered in time to make it seem like a handshake.

He was Roger Pring, a Brit who pronounced his last name with the same snappish accent his countrymen might have used to say prawn. I liked him at once. He was friendly and awkward, a big teddy bear of a man, like Jerry Garcia, I thought, without the buggy stare. Walking toward a parked van, I asked, “Student or cooking teacher?”

“I’m the general assistant, fake sommelier, jack-of-all-trades, and shit-shoveler,” he said quickly, making it sound rehearsed.

As Roger loaded my gear in the boot, a woman in the van made room in the back for me. Her name was Helen, another Brit, perhaps a few years older than I, with a dark-complected elegance that originated from somewhere between Greece and Egypt. She introduced herself as a longtime admirer of the chef’s food. I couldn’t help feeling surprised to learn that she was enrolled in the program.

She seemed almost wary of learning how to cook. “I’m afraid I won’t be much help with the nitty-gritty,” Helen confessed.

“That’s nothing to worry about,” I said. “We’re all pretty much in the same boat.” I glanced briefly at her face and noticed a flutter of uncertainty. “You are eager to learn, though?”

A smile played nervously at the corners of her mouth. “I’ll probably do better as an observer,” she said. “Besides, I’m not actually a full-fledged member of this team. My status is more guest than student.”

I wasn’t sure what she meant, but as we drove south along the autoroute, rattling from Lyon into Burgundy, a heavy foreboding hit me as Roger and Helen made little jokes about some minor dramas at the cooking school. The car became full of crossed parenthetical remarks. From what I could piece together, there were still many last-minute arrangements being ironed out, among them the food for tomorrow’s menu and room assignments and a shortage of burners on what the Brits called the cooker, which I took to mean the stove. It sounded as though they were feeling their way through the process.

“Is this the first session of the season?” I asked innocently, trying not to betray my concern.

“The first?” Roger echoed. “Oh…yes…definitely…you could say that.” He threw Helen a funny little glance.

“It’s the first one,” she said, smiling weakly, “…ever.”

It took me some time to realize this wasn’t a joke. This was their maiden effort, a test run to see if they could get the Robert Ash Cookery School off the ground. Somewhere in the back of my mind, I heard Donald O’Connor saying, “Hey gang, wouldn’t it be great if we could put on a show?” My heart sank. How could I have made such a colossal mistake? The website for the school had made it sound like a well-established affair. It described an eminent chef and his wonderful kitchen—no, a “main teaching kitchen,” which had impressed me no end—“equipped to a high standard, with every conceivable tool of haute cuisine.” There were gorgeous pictures of food and of previous classes, which, I was to learn much later, belonged to another cooking school in another country. In the calmest voice possible, I asked, “How many other students will be there besides me?”

After a long pause, Roger said, “I’m afraid you’re it for now, mate. But that shouldn’t be a problem. We’ve invited a few friends down from London to fill in the ranks. It’s going to be a lot of fun.”

Fun was nowhere on my list of perks. Fun was skiing the back bowl at Vail. Or combing the stalls of rural flea markets. Cooking school was supposed to teach the mastery of skills and discipline, perhaps be artistic, even a bit philosophical. Only fun in the sense that we could eat our mistakes.

I sat in the enveloping silence and tried to organize my feelings. There were reasons I’d chosen this particular school to begin my odyssey. The hills of Burgundy held a very special place in my heart. Years ago, I’d crossed them on a bicycle, drinking in the ancient beauty as well as the best of its wine. Nothing had prepared me for the experience. The landscape surrounding that weave of roads unlike any I had ever seen, the colors more dazzling and intense: the greens were greener, yellows yellower, with ripe fields of purple, brown, and red sewn like a big patchwork bedspread. The hills that plunged down to the flatlands were covered with gnarled vines. And its cuisine was in a category all by itself. A wanderer coming upon unexpected treasure, I had gorged myself on the rustic, hearty comfort food found in typical Burgundian kitchens—the beef stews and coqs au vin; the encyclopedic cuts of charollais slathered in rich wine sauces thick with onions, mushrooms, and lardons; the slices of jambon persillé; and the knuckle-size escargots roasted with garlic and oil.

It seemed fitting to start here. The food would be straightforward, honest, free of the long, elaborate preparations that complicate so much of French cuisine. I’d feel more confident learning to make reductions and pâtés and soufflés after a week or two with the basics. Besides, Robert Ash was English, which meant that I could ease into the instruction without having to hurdle the language barrier. My French was decent, not great; translating each drill would slow things down and exhaust me. And Ash himself sounded like a wonderful character. The website described him as “chef-patron of London’s legendary and award-winning Blythe Road Restaurant.” The place meant nothing to me, but I loved the sound of chef-patron, the whole idea of paying homage to a master.

I just wished to hell that he’d taught cooking before now.

Roger assured me that Ash was the real deal, but I wasn’t so sure. I was picturing myself as a guinea pig for these aspiring foodies, Chef Ash and his Merry Men.

I felt better when we turned off the highway onto a wobbly country road flanked by farms and vineyards. The land on both sides looked deep-set and hidden. I squinted through the dark into the shapeless night. It was only through some effort that I could glimpse a village. Beyond the rise of the hills, the treetops were tipped in silver moonlight; otherwise, it was difficult to make out much in the head-lamp’s pencil glare. My memory, such as it was, had to fill in the blanks. The last time I was here, they had just finished the grape harvest, the vendange. It was in the fall, right after the trees had turned color, and there was a soft rushing as dozens of farmers hurried from vineyard to vineyard with the stubborn preoccupation of accountants at tax time. Sunlight shot through the vines with tendrils of honeyed hues, and the scent of wine, faintly tart and tangy, hung over everything. There was so much to absorb. I had just gotten married, and it was difficult to reconcile my thoughts and feelings about this surfeit of beauty. From that point on, one thing was clear: My heart no longer belonged solely to the woman on my arm but to this glorious countryside as well.

I recalled all of this as the car trundled on, past the turnoff to Villefranche-sur-Saône and a skein of tiny villages nestled below the Beaujolais slopes. Through the open window, the night air felt cool and thick, with a peaty musk that suggested eternity. My spirits continued to rise with every mile.

“You’re going to love this place,” Roger said, and I couldn’t help but agree as we cruised through the intersection at Les Massonnays and turned onto a gravel road, beyond a gatepost that said RUE DU LAC.

Of course, I couldn’t see the lake through the copse of trees, but I could feel its presence. The house, however, was bathed in light. Far from the noble twelfth-century farmhouse promised by the cooking-school agent, it was a modest stucco affair framed with blue shutters and surrounded by a moat of gardens that appeared to be in full bloom. Its appearance, from what I could see, radiated bourgeois caution. A middle-aged man with a kind face opened the door, and suddenly I was in a bright, airy kitchen on whose counters stood perhaps two dozen bulging grocery-store bags tilting under the strain. “Forgive the mess,” said the man, Paul, herding us into a pleasant parlor. “Bob just got back from the local Carrefour, and we haven’t had time to unpack.”

“But you left four hours ago,” Roger said, fingering through one of the cartons.

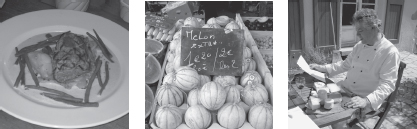

“Five, actually—not that it mattered. You should have seen him. Bob was like a kid in a candy store, marveling at melons and aubergine. ‘Look at this fennel! Smell this Époisse!’ I couldn’t get him out of there. If the store hadn’t closed, we’d still be shopping.”

I settled into a club chair and took off my jacket. “Is he here? I’d love to meet him,” I said, glancing about for a suitable suspect.

Not a chance, I was told, not tonight anyway. Chef Ash was secluded following his ordeal, resting up for tomorrow’s lesson. It crossed my mind that he might be off somewhere rereading the How to Teach Cooking manual.

I had a restless night’s sleep. The ancient pipes under the floorboards wheezed at a frequency so low and husky it sounded like snoring in the next room. Toilets flushed in SurroundSound. From somewhere in the snug house came a lullaby of ticking, perhaps a clock or someone’s ham radio making contact. Of course, none of these compared with the jangle in my head. I heard from the full cast of characters barnstorming through my life, their words of advice and warnings, their complaints, demands, opinions, ultimatums, even their recipes—for success and failure, Dr. Freud might have suggested—and for several hours insomnia coursed through my body nerve to nerve.

No one else was up when I crawled out of bed sometime after daybreak. The house was cold, clammy with rural damp. I took a short walk through the small, medieval village—a cluster of decrepit houses—and around the lake, where a few greedy fishermen had already thrown their lines in the water, hoping to surprise their catch. As I walked, the morning revived me. The cool air was refreshing and filled with a grassy extract that tickled my nose. When I got back a half-hour later, the kitchen was in full swing.

“We thought you might have hitchhiked back to Lyon,” said a pale, dainty brunette with a sort of Gainsborough brittleness who introduced herself as Susie Hands-Wicks. A neighbor of the chef from a London suburb, she and her husband, Paul, had offered up their vacation time to assist in the cooking school’s launch. “Roger suspects you are disappointed with the setup.”

“Not at all,” I lied.

“In which case I can promise that you won’t be disappointed with the food. Bob makes the single best guinea fowl I have ever tasted. And his duck confit…” she said it while touching her heart as if blessing a sacred fire…“his duck confit is a minor miracle. You could close your eyes and think you were eating…”

“Duck confit.”

The voice had come from behind me, and I turned to find a tall, wide-shouldered man battling schoolboy plumpness, his forehead jeweled with sweat. He had an impressive quiff of salt-and-pepper hair that appeared to be lacquered in place, making him look like a doo-wop star on the revival circuit. Above the pocket of the white chef’s coat, stitched in script, was Robert Ash. He gripped my broken hand with an excessive firmness that served as advance notice of our teacher-student relationship.

“Don’t believe anything Susie tells you,” he said affectionately, throwing a quick, professional glance at the vegetable she was chopping. “She’s paid to say that. Meanwhile, check out her scrawny waistline. Mother of two teenagers. Does it look like she’s eaten very much rich food lately?”

Susie rolled her eyes skyward and touched his sleeve.

A look of concern tightened on Ash’s face. Leaning over the cutting board, he said, “A little finer, darling.”

The attention to detail was reassuring. On first impression, it would be safe to say, his appearance didn’t inspire. Ash seemed young to be considered a chef-patron, let alone having the distinction of being called master, although I am sure he had tended his fair share of stovetops all over the world. And he had a restless spirit that made him seem distracted in regard to the rigors of French cooking. I stared with a kind of foreboding at his florid, rakish face, wondering if there wasn’t some excuse I could make to leave a few days early. The last thing I needed was to waste time studying with a guy who was only as good or as technically inventive as I was.

They were in the midst of some preparation for our lunch, which I was told we’d begin cooking in earnest during the morning class. In the meantime, Roger—who, it turned out, owned the house at Rue du Lac and was letting his friend Ash use it for the school—recruited me for a croissant run to the next town. The prospect of freshly baked French rolls was an indulgence I’d been craving, but the pâtisseries in Pontanevaux and Les Maisons Blanches were closed when we got there. Monday, apparently, was the baker’s day off. Supermarket baguettes loomed in our future until we stumbled across a hidden pâtisserie in Crêche-sur-Saône. In the main square of the town, we picked up the insanely sweet scent of butter and followed it into a side street, where we found the bakery.

The place was filled with desperate characters like us who had come looking for their morning fix. When it came our turn, Roger ordered a half-dozen bressans, peculiar breast-shaped loaves named after the town of Bresse, which are heavier than brioches and made from maize. The old woman behind the counter dumped them from her baking paddle into Roger’s hands, initiating a clumsy juggling routine. “Shit…Jesus!” he sputtered, shoveling them onto the glass. “She must have just taken them out of the oven.”

The woman regarded us with amusement. Roger gave her a look that verged on murder. She held out a bag, and for a moment I worried that he might hit her. He swept the loaves into the bag, grabbed a few baguettes, and paid. “Thank you,” he said, turning his head away before muttering, “Cheeky little fucker.”

To soothe Roger’s trauma, we shared a hot bressan in the car, eating the halves much too fast and knowing that we had never feasted on such dense, creamy bread. It fairly wept butter. A brief debate ensued, during which we swore an oath not to break into another one, although there came a point when it seemed that only manacles would keep us from tearing open the bag. We rolled down the windows, hoping it would help to discourage temptation. Still, the smell of the bakery followed us all the way back, making my stomach churn with hunger.

As we turned into the driveway of Rue du Lac, I commented on the unusual siting of the house. The property, which stood less than a thousand feet from the Saône, looked over a small lake on the other side. There was an unobstructed view of the Beaujolais hills: Fleurie loomed to the east; its northern edge tilted gently toward the vineyards of St.-Amour; and the westerly treeline was opened a hair, thanks to an obstinate wind, exposing the slopes of Chenas. Without even looking, I knew the back of the house faced the vaunted soil of Pouilly-Fuissé, whose grapes had fueled many a festive glass of mine. None of this, of course, had been visible upon my arrival. But in the daylight I could see the remains of the crumbling rock formation on which the house now stood proudly.

Roger explained that it had been abandoned in 1986 by a pork butcher from Mâcon who went a bit crazy, tried to shoot his wife, and ended up going bankrupt defending himself at trial. “In the time-honored English tradition, we bought the house from his creditors,” Roger said.

Built in 1820 and renovated by Roger and his wife, Sarah, the house was cozy, with rectangular low-slung rooms, chair rails and molding fashioned from apricot-colored woods, and worn irregular squares of terra-cotta on the floors. The upstairs hallways were lined with a warren of simple, monastic rooms. It was heartening the way the house invited lemony shafts of sunshine during all intervals of the day. Adjacent to the living room, Dutch doors opened onto a terrace, one of the most relaxing oases I had ever seen, with a reflecting pool and a few chaises longues and wisteria intertwined with orange vines dangling from trellises. If the wind was blowing in and you listened hard, very hard, it was possible to hear the slow lap of the lake, or at least a sound that could be reasonably interpreted as water.

The kitchen was spread out, with a tiled checkerboard floor and two windows over the sink looking out onto the pleasant little garden and a pond beyond that. An eye-popping supply of cookware teetered in the overhead cupboards. There was a light supporting symmetry to it all that seemed custom-made for cooking. As we sat down to coffee, I saw in one easy glance that the room had yet to be put to the test. The counters were still shiny, the sink a stainless white shell. The stove (or should I say the cooker?) seemed just to have come out of the box.

Robert Ash fussed through the kitchen noisily while we ate the bressans; he had apportioned the room into workstations by the time breakfast was finished. Chopping boards and utensils were laid out by each position, close enough together so that Helen, Susie, and I could observe each other’s work yet cook without bumping into each other. (Paul and Roger were content to hover, as opposed to cook.) Bowls stuffed with fragrant herbs rested on a trivet in the center, and in the sink was a metal funnel-shaped gizmo I’d never seen before. Each of us received a crisp white apron and a blue notebook full of sleeves into which we could slip our recipes. Like a symphony conductor delivering the score, Ash handed out an inch-thick sheaf of instructions for the upcoming session.

“Well,” he said, wiping his hands on his apron, “we ought to get started right away if we intend to have lunch ready by one.”

The menu was ambitious. If I read it correctly, we were making a salad of endive and roasted almonds garnished with bacon, avocado, and feta cheese, followed by that old Lyonnais standby, salmon cooked en papillote with braised vegetables, and a dessert of pears poached in port. To my thinking, it seemed like a wonderful way to begin our work. We were excited, the way that children get on the first day of the school year, when everything is new and the freshly scrubbed classroom looks like the backdrop for a Norman Rockwell painting.

If lunch alone had been our goal, we might have breezed through the preparations. But Robert Ash, as it turned out, was almost singlemindedly obsessed when it came to cooking, teaching cooking, and from the outset the workload was more than any of us had bargained for.

Our first order of business was to formulate a “house dressing” that Robert said becomes a cook’s signature—one used not only on salads but also as a base for almost every kind of dish, hot or cold. When made thoughtfully, dressings morphed into marinades, starters, jus, or dipping sauces. Naturally, this required certain basics—a good, fragrant olive oil and red-wine vinegar, a half-teaspoon of coarse-grain mustard, and plenty of salt (even a little too much for my taste). As for pepper, Chef demanded we use the stronger white variety on everything, for mostly aesthetic reasons, along with a little sugar to balance out the acidity. Although still fairly unaccustomed to each other, we decided to exert our independence by including a handful of chopped shallots, blended thoroughly with enough raspberries to give the mixture a decadent blush.

Ash didn’t seem pleased. He eyed the dressing suspiciously, as one might a dinner guest who showed up in a monocle and bow tie. The shallots didn’t bother him, but the creamy pink, he said, seemed prissy, undignified. And it made the dressing thick. To compensate, he drizzled a scant two tablespoons of it over a truckload of endive, then used his fingers to toss it, coating each leaf with dressing.

Helen wrinkled her nose at the jungle procedure. Instead of following suit, she mixed her portion with two soup spoons, clacking them like castanets against the metal bowl. Wordlessly, Ash took the spoons out of her hands and flung them into the sink, watching as she joylessly but grudgingly dipped her fingers into the brew, which, I suppose, was the same approach Helen might have taken the first time she went skinnydipping.

“From now on,” Ash announced, “everything we do is going to be hands-on, in the strictest sense. We’re working with food here, and that means we have to touch it, smell it, feel it, taste it. This kitchen is no place for the squeamish. Trust me. If you handle the ingredients timidly, it’s going to come through in the final result. Now let’s roll up our sleeves and have a go at it.”

Ash’s tactful rebuke blew right past Helen. After he demonstrated how to juice lemons and separate eggs through our fingers rather than the more conventional ways, she rushed to duplicate it, cooperating but also pointedly washing her hands after each procedure. Helen was a terrific sport, and so was Susie, who had good homemaker’s instincts for the practical, the efficient, the necessary. I had pegged them both as earnest British university grads who, forsaking any real ambition, had settled comfortably into the background of life. Had they been less congenial or part of a larger group, I probably wouldn’t have developed a rapport with either one of them. Our intimate cooking arrangement, however, was an excuse for me to appreciate their engaging lightness. Both women brought with them a style, an unself-conscious amiability that relieved the burden of formality.

Our long morning session, with Roger providing off-color commentary, gave all of us an appreciation for time management, considering Chef’s breakneck schedule. The four of us worked like mad, in constant motion. We made a big salad and began a preparation for duck confit that would stretch over three days, necessitating daily tweaks. After tea, Bob presented us with two whole sides of wild salmon, enough, I thought, to feed the French fleet, and explained that we would be using every inch of the fish for several different dishes.

I love salmon, but the kind I got back home was mostly farm-raised—as pale as a redhead on the beach, with only a suspicion of flavor to suggest its seaworthy origins. These babies announced their pedigree before they even hit the table. They smelled like honest-to-god fish, just briny enough to recall that last low tide at noon, leaving the faintest hint of sweetness on the nose. If I hadn’t had my glasses on, I would have sworn they were painted, they were that intense, a deep carroty orange streaked with red and rippled silver. They felt satiny after we washed them, with a spring to the touch, not the kind of fish that bent like a rubber hose.

Bob sliced six fillets, each about an inch thick, from the fattest ends of the fish. These we reserved for the next day’s lunch. We were instructed to skin another portion by holding the tail end with our fingers, making a small incision in the fish, and simply pushing the knife through, in the hairline crevice between the flesh and the skin, at a thirty-degree angle. Like magic, the two sides separated without leaving so much as a fleck on either piece. (I began keeping a list of things to do once I returned home, and at the very top I wrote: sharpen knives.) We cut these into half-inch slices and layered them in a Pyrex bowl, for an appetizer of salmon ceviche—Bob pronounced it sah-vitch—cured with a citrus fruit marinade. Leaving nothing to waste, we packed the tail ends under a thick bed of salt, sugar, and dill for gravlax, to be served a few days down the pike, alongside a honey-mustard dill mayonnaise.

As we prepared each of these recipes, Chef interrupted often with a bonanza of technical tips. For example, much later, when readying the ceviche, Bob showed me a nifty little flourish to enhance the presentation. We found a beautifully shaped cucumber, pulled the zester over it from stem to stern, then cut it in half lengthwise and scooped out the seeds. We then shaved each half into paper-thin moons, which we overlapped in the center of the plate to create an impressionistic flower shape, before mounding the fish on top. The pale green and orange provided a stunning contrast, in addition to the fashion statement the dish made when it was presented at table.

Those recipes would stay with us always, as convenient go-to options. We’d make them effortlessly, without much forethought, knowing they’d turn out as perfectly as a peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich, and with about as much originality.

The salmon en papillote, however, was a revelation. The exotic locale notwithstanding, it more or less justified the entire cooking-school experience—and this, as hard as it is to believe, on my first day out of the box. This was just what I’d had in mind. I congratulated myself for coming here—my fantasy was beginning to take shape. I had made this dish often at home, but my preparation was a car wreck. Roger, who hovered like an evil insurance inspector while we cooked, hit it right on the head when he said, “It seems like you just stuff all this shit in a paper envelope and throw it in the oven—bang, bang, bang!” My salmon at home wasn’t even that elegant. I used aluminum foil as my papillote and piled on any odd vegetable lurking in the kitchen. If the celery looked about shot, I chopped it up and chucked it in. A can of chickpeas left over from the last century? Sure, why not. I once even threw in a sorry-looking flap of roasted pepper I found floating in a jar of sulphur-yellow liquid. By the time I folded up the sides of the foil, it resembled a stealth bomb.

Robert Ash’s version carried with it the elegance that such a dish would embody were it ordered in a fine-dining establishment, and there are those brave souls who wouldn’t shrink from his rule of placing the unopened pouch in front of a guest and ceremoniously slicing through it so that everyone at the same time sees how it turned out. A stunt like that takes courage, considering the disasters I’ve turned out, but from all evidence based on our endeavors, it never fails to produce sensual delight. It required a little more effort than my lethal attempts, but the result was well worth it:

SALMONen papilloteWITH BRAISED VEGETABLES

4 Tbl. butter

½ cup carrots, shredded

½ cup leeks, shredded (white part only)

½ cup red onion, julienned

½ cup mushrooms, julienned

2 tsp. chopped fresh tarragon

4 sheets of parchment cut into 14-inch rounds olive oil

1 lb. 4 oz. fresh filleted salmon, cut into 12 equal pieces salt and white pepper

12 tarragon leaves

4 knobs (1–1 ½ Tbl. each) butter

4 Tbl. dry white wine

4 Tbl. chicken stock

4 tsp. finely chopped shallots

Melt the butter in a skillet and add vegetables with the chopped tarragon. Sauté gently until soft. Make this beforehand and set aside so it cools, to keep the vegetables from tearing the paper parcels.

Preheat the oven to as hot a temperature as possible—450° or hotter.

Fold each of the paper rounds in half and brush with oil. Lay the rounds flat and place one-fourth of the vegetables on the front half-moon of each disc, then lay three pieces of fish on top at a 45-degree angle to the fold. Season both sides of the salmon with salt and pepper. Press a tarragon leaf on each piece of fish, add a knob of butter, 1 tablespoon of white wine, and 1 tablespoon of chicken stock, then strew 1 teaspoon of the shallots over the top. Seal the paper parcel by folding over and crimping the edges—making a ½-inch fold, moving 2 inches up and folding over again, pressing down tightly, then repeating until fully sealed.

Set the parcels, well spaced, on a baking sheet, and bake 4 to 5 minutes, or until they puff up. Serve immediately by cutting them open. (Lots of steam emerges; use extreme caution.)

Serves 4

How in God’s name, you might wonder, are you supposed to measure a knob of butter? This is something that can’t be answered with any precision. Bob just lopped off hunks of the butter bar and judged them to be suitable specimens. “Smaller than a door knob,” observed Roger, “and larger than my wife’s.” To my eyes, on average, they looked about the size of a man’s knuckle. A reasonable knob of butter melts through the entire serving, layer upon layer, and delivers a sweet, richly flavored fillet that stands up to the savory combination of ingredients competing for attention.

The great thing about this recipe is its efficiency: It can be assembled ahead of time and slipped into the oven just as everyone is unfolding napkins. Bob encouraged us to improvise: Susie added fish stock instead of the chicken, and a splash of dry sherry; I replaced one piece of salmon with two shrimp for variety; and Bob said that monkfish or even halibut worked to great effect. Meanwhile, we attended to the other dishes in various stages of development and banged out our dessert.

We worked so furiously that morning, about as fast as my mind could follow, that when Chef announced lunch, it seemed more a reprieve than a reward.

Everyone gathered around a picnic table on the terrace, which had been set by Paul. Framed by the lovely garden, it was a most agreeable spot; we had sun on our faces and the thin scent of orange blossom swollen by heat and Carole King who serenaded us from hidden outdoor speakers. It was my impression that this group of friends sat down to eat often together. Everything revolved around Bob Ash’s cooking, but his virtuosity, rather than glorifying him, had a clubby, embracing effect. It was generous of them to include me in their gay familiarity, considering I’d known them for under twenty-four hours.

Paul, especially, seemed like a good sort. He was the type of middle-aged man I recognized from those quirky British TV mysteries, the kind who lives alone in a Midlands cottage, wears cardigans, smokes a pipe, maybe raises pigeons, and happens to overhear a neighbor confess to his wife’s murder. A surveyor by trade, Paul introduced himself to me as the sous-plongeur (Roger being our chief dishwasher), a noncook, “just an eater,” as he pointed out, who was prepared to handle any grisly job so long as he could gorge himself on Bob Ash’s food. “I’ve waited weeks to enjoy this lunch, even if a bunch of rank amateurs are preparing it,” he despaired.

Roger proposed a toast. “To our valiant chefs in the kitchen. Lord have mercy on us all.”

The meal, to our credit, had come together into a well-constructed affair, and we cleaned our plates with crusty bread from the bakery in Crêche-sur-Saône. I can’t remember now how many different wines we tasted with lunch, an endless supply of bottles from the area’s best producers, including a gorgeous sweet Muscat de Beaumes-de-Venise that accompanied a platter laden with special cheeses. By the time we got to dessert, I could only poke wearily at the plump-bellied Anjou pear lolling in a puddle of spices and port wine. It seemed indecent to leave it on my plate after all the care that went into making it:

POACHED PEARS IN PORT

6 Anjou pears, peeled

3 or 4 whole cloves

1 750 ml. bottle cheap port

4 cinnamon sticks

ground allspice, big pinch

sugar, to taste

chervil sprigs, for garnish

Choose good, well-shaped pears with fat bellies so they stand up in the pan; otherwise, take a little slice off the bottom to ensure they stay upright. About ½ inch from the top of the pear, make a small horizontal incision with a knife, being careful not to cut all the way through the pear, so that it can be cored without taking off the top. Then trace a circle in the bottom of each pear with the corer, following the circle inside, deeper and deeper, as you core it until you hit the incision and can remove the core.

Choose a pot that will hold all 6 pears yet is small enough so they fit snugly. (If necessary, add an extra pear in the middle of the pot.) Add the bottle of port and the spices and top with enough water so that the upper quarter and stem of each pear remains dry. (If there is any old red wine around, throw that in, too.) Bring to a boil and reduce to a trembling simmer until the pears are tender.

Remove the pears from the pan and bring the liquid to a rapid boil, reducing until it is the consistency of maple syrup and coats the pears. (Add a tablespoon or two of sugar if the reduction isn’t sweet enough.) Spoon the port reduction over the pears, drape a little chervil around each stem as a garnish, and serve warm.

Serves 6

After dessert, I made my way upstairs for a well-deserved nap. Everyone else, except the chef, tromped off to a wine tasting at a nearby chateau, where, after subhuman moans of indisposition, they reportedly drank more wine and ate more food. It is anyone’s guess what I dreamed about during that interlude, although it is safe to assume it involved at least three types of antacid and Carolyn, immodestly clad.

Stupefied though I was by food and drink, I slept fitfully. Lunch was fermenting in my stomach like an underground nuclear test, and I hadn’t heard from Carolyn since arriving in Europe. I checked in via Roger’s Internet setup and came up cold; she was either too busy packing or shopping for the trip. So I emailed Lily a description of everything I’d learned so far, even though we’d spoken on the phone a few hours earlier.

Around four o’clock, I heard a rumbling downstairs in the darkened kitchen and was surprised to find Bob ransacking the cupboards like a hungry raccoon. When he saw me loitering on the periphery, he thrust a glass of wine at me and bellowed, “Let’s get going. We’ve got a dinner to prepare.”

This turned out to be a stroke of wonderful luck: just the chef and I, one-on-one in the kitchen. The syllabus designated tonight’s menu as guinea fowl with pancetta in a cèpe sauce, and I offered my services like an obedient slave. Even squeamishness could not shake me from the anatomy lesson at hand. Ash taught me the proper way to remove the breast from any game bird: making an incision in the skin at the top of the breast and gradually paring the meat away from the bone, working my way down the breast with short, delicate strokes from a seriously sharp knife to separate the connective tissue. Once that was done, I clipped off part of the wing and then went through the joint at its socket and cut out the wishbone before removing the entire piece. It was much easier than I’d expected—and it paid dividends. For years, I’d watched the butchers at Stop & Shop take apart my birds with several flashes of their knives and admired how they made the trimmings disappear, like David Copperfield. Ash nearly tackled me as I attempted to launch our odds and ends into the trash bin.

“Are you out of your mind?” He cradled the spoils like treasure. “This gives us the start of a beautiful stock.” He wrapped the discarded chicken in butcher paper and returned it to the fridge. Then he leaned into the trash, sorting through it with ferocious vigilance, to make sure I hadn’t deep-sixed more of his precious waste. “Everything gets recycled. Nothing is thrown away until we’ve wrung every last use out of it.”

Before the serious cooking got under way, Ash clapped his hands sharply like a stern headmaster and waved me toward the door: “Would you go out to the car and get Pet Sounds, please?”

There was a longstanding tradition in his kitchen that prep work jumped to the tempo of the Beach Boys. As I cranked the volume, Bob left the stove to hammer out a few chords of “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” on the upright piano standing against one wall of the dining room. He played with the same flair with which he cooked: confident, graceful if a bit sloppy, with a nice economical groove that danced all over the incongruities.

“This is the album that did it for me,” he said, returning to the mise-en-place with almost post-coital pleasure. “Never fails. Those amazing Brian Wilson licks and harmonies give me such a charge.”

I protested only to myself, recalling how, for most musicians, this album was the Holy Grail. Paul McCartney once told me that his goal for Sgt. Pepper’s was to produce something as musically compelling as Pet Sounds, but truthfully most of it bored me silly. As “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” gave way to “Don’t Talk” and “Let’s Go Away for Awhile,” I was unable to hold my tongue any longer, railing at the whiny filler between a few glittering gems. This fired up Ash even more, and we sparred through the rest of the cooking session, talking about the things that mattered most in life: food and rock ’n roll.

As the afternoon wore on, the two of us developed a companionable rapport. We were exactly the same age and had spent most of the seventies in service to rock ’n roll: Ash playing guitar behind Jimmy Ruffin and Rick Wakeman, and me with Bruce Springsteen. “From the time I was eighteen, I played in a band that backed American artists, groups that had one hit and came to England for personal appearances without their own musicians,” he said, ticking off Martha Reeves, Doris Troy, and Desmond Dekker, to name a few. Performing invigorated him and brought in decent money, which provided the freedom to pursue other fancies. When I asked him why he gave it up, he just shrugged in that weary way only another musician understands.

Food—good food—had never entered into the equation. Being on the road, with all those wasted hours running from town to town, from gig to gig, from crazy scene to crazy scene, there was no time or even the inclination to eat a proper meal. We lived on a steady diet of fast food, the tasteless sandwiches grabbed on the way out of town from an all-night drive-in or the spare bag of chips someone had abandoned in the car. These were the days before limos and MTV, when life on the road felt like a long forced march.

“The food came later,” Ash said. He’d cooked as a kid, as I had, but nothing very serious. And his mother’s culinary undertakings verged on the criminal. She could take a gorgeous piece of meat, a well-marbled ribeye, for example, and turn it into a missile-defense shield. “That’s why I started cooking for myself; I figured I could make anything better than she did.”

He taught himself to cook, but all he wanted was enough experience, a few imaginative recipes, so that his own family would never have to suffer the gastronomic misery of his childhood.

When he hit his thirties, however, the strategy went awry. He took a couple of cooking classes in the downtime, between tours promoting Rick Wakeman’s Gospel album. “I was getting very adventurous, far from being just a home chef,” he said. “My kids, who were little at the time, used to sit on highchairs and watch me stuff game birds with pancetta and prunes.” His wife, Jackie, entered him in the Observer’s Château Mouton-Rothschild contest for amateur cooks. Bob made a filleted four-rib of beef in a coriander sauce with mussels in snail butter—and won first prize. “I thought they were joking,” he said.

Quite the contrary. The Observer sent him to Burgundy for a stage with cranky Claude Chambert, from whom he learned how to think like a chef. Then he parlayed the experience into apprenticeships at various upscale bistros until he became chef de cuisine at the Blythe Road Restaurant, which was on the cutting edge of London’s culinary renaissance.

“I thrive on the mayhem in a restaurant kitchen,” he said, while instructing me how to trim the breasts evenly so they were identical, as precise as petals. “It never stops—six or eight hours of absolute chaos. It’s like rock ’n roll to me. There is a rhythm to it that you hook into and it takes over your body. The background music is solid shouting—not anger, just everyone shouting back and forth. And then, suddenly, it’s all over and you down that beer in a flash.”

I could see the manic intensity percolating in Bob when he cooked. He handled the knife like a trusty, beat-up Strat, punishing its grip the way your hands bite into a twelve-bar blues. His fingers looked like cocktail franks, stubby, hardly what you’d expect of a flash guitarist, but he used them with assuredness. When he cooked, it was without the graceful body language that my friend Sandy displayed at the stove. There was no nimbleness or finesse, no expression of formal training. His expertise—like that of his guitar playing, I am certain—was learned on the street.

But he was good, damned good, the kitchen equivalent of an outsider artist. I loved his whole approach, his sense for the rhythmic mix of bluff and guess that distinguishes sumptuous cooking. In love with all things flavorful, he worked with an unchecked passion that seemed genuine even now, after all those nights on the line feeding hundreds of impatient strangers.

I knew enough not to interrupt with questions as we pieced together a cèpe sauce, but I could not help throwing sidelong glances at his stubby fingers as he sliced through an onion. He slid the knife blade smoothly forward and down through the onion’s slippery surface as opposed to my savage, choppy technique. His dark eyes twinkled as he caught me trying to imitate his moves.

“Here, try this,” he said. By now my bad hand was throbbing, but he grabbed my arm from behind and guided it in a steady sawing motion weighted by a slight arc. “You want to slice across the onion, pressing only slightly, and let the knife carry you through the flesh. Chopping, which we’ll do afterward, is an entirely different process.”

While the sauce simmered, we began making a chicken stock that would evolve in stages over the next few days. I had always wanted to make my own stock, one that was infused with tons of rich chicken flavor, but I despaired of the fuss that went into it. Bob, in his offhand way, made it a painless affair. He used everything he could get his hands on for stock—the guinea-fowl carcasses, any old bones that were left on dinner plates, wings, necks, feet, unmentionables, whatever enriched its flavor. “I don’t believe in artisanal stocks,” he said, articulating the word the way George W. said liberal. “My purpose is to give it an honest, homemade taste, as opposed to something to admire as if it were a delicacy.”

BOB ASH’S CHICKEN STOCK

Preheat the oven to 425 degrees.

Roast the carcasses of two chickens or any fowl until they are browned. Deglaze the roasting pan with a little white wine, scraping up the brown bits, and transfer everything to a bowl. Deglaze the pan a second time with water and throw that into the bowl as well.

Quarter 3 onions (with their skins on) and sauté in 2 tablespoons of vegetable oil, in a stockpot, along with 2 slim leeks, 2 carrots, and 2 stalks of celery, all sliced in ½-inch chunks. Throw in a handful of parsley stalks (minus the leaves) and 2 bay leaves. When the vegetables are softened, add the carcasses and deglazing liquid and cover with water (about 3 quarts).

Bring everything to a boil, cover, and simmer 2 to 3 hours, skimming the fat from time to time with a spoon. Season with salt to taste.

Makes 2 quarts

“Tomorrow, we’ll parse the bones in a colander, then strain everything through a chinoise [a fine-mesh conical sieve on legs—that funnel-shaped gizmo I’d seen in the sink] before putting the finished stock in the fridge,” Bob said.

I managed to pinch a ladle of soup and tasted it. It was exactly as he’d promised: not fancy, but honest and delicious, strong, well seasoned, redolent of roasted meat.

“Better than that canned stuff you use in the States?” he asked, smirking.

I admitted it was. He grinned and balanced a load of sizzling plates on my arms like the pigeons on the tourists in St. Mark’s Square.

“Let’s rush these to table, lest our friends think we’re jerking off in here.”

Even money says it never crossed anyone’s mind.

Dinner was a ridiculously happy affair. It was long and lazy outside on the flagstone terrace, with a chorus of ribbonlike laughter accompanying each amazing course. We ate well: thick slices of seared foie gras in a port gelée, followed by the guinea fowl cooked to a rosy perfection and buried in the decadent mushroom sauce. The cheese selection had grown even more expansive since lunch. I picked at it sparingly, feeling a wave of protest rising within me but knowing too that I might never enjoy such a luxury again. Afterward, guitars were dragged out, and Ash raced through what seemed like the entire Dylan songbook, singing such forgotten gems as “Hollis Brown” and “With God on Our Side.” He played spot-on, with unflinching easy brio though a little helter-skelter, with Paul strumming impishly behind. I even joined in on a few numbers until my damaged hand gave out.

Across the room, Susie and Helen harmonized to the teasing refrain of “I Shall Be Released.” There was a palpable thrill in their performance: “…any day now, any day now….” My voice, high and hard, burst through with all the hope the words intoned, but it was well past two in the morning and I was still hours from bed.