CHAPTER 8

Maintenance Phase

When I was young, someone told me that 20 percent of life is spent on maintenance. At the time I bristled at the idea. I was too busy for that.

As I have grown older, I find that I spend a lot more time maintaining everything, not the least of which is my dietary health. I cook most of my own food now, and I plan time for exercise and relaxation. It is my goal to convince you, even if you are still young, that health maintenance and disease prevention are essential, and it starts with what and when you eat.

I think of reflux maintenance as the stage when good, long-term habits are formed. The habits that are important in maintaining health involve aspects that are not specifically diet-related. For example, if you have reflux and your spouse gets home from work at 8:30 in the evening, then dinner together may be a problem. Negotiations have to take place between partners to reach consensus, a way of managing meals that works for you both.

You may also have to change your work schedule and your social life. A psychotherapist who works until 9:00 p.m., for example, might have to take a break from 5:00 to 6:00 for dinner.

You will need to take your work situation and family responsibilities into consideration. In my practice, the biggest fight my patients face is over dinnertime, specifically the time the patient can arrive home, prepare dinner, and eat. Dinner at 6:00 p.m. is no doubt one of the biggest adjustments for most people. Dinner should be your special meal, but it should not be the meal when you refuel for the day. You should try to obtain 75 percent of your calories each day before 5:00 p.m.

It is important to emphasize that late-night eating is the single most important risk factor for many refluxers. It probably does not matter how “healthy” you eat if you’re eating it late.

I have had many patients whose reflux remained recalcitrant until they were able to move dinner to an early hour. In addition, lying down right after dinner and late nights of heavy drinking are incompatible with reflux health.

The maintenance phase involves planning meals, cooking, bringing food to work, and training friends and family. You must establish routines for meals, snacks, and even dining out. Introduce your dietary needs to the server at restaurants: “Hi, I am on a special diet. I would like to know what grilled fish or fowl is available that does not have butter or sauce on it—olive oil is fine.”

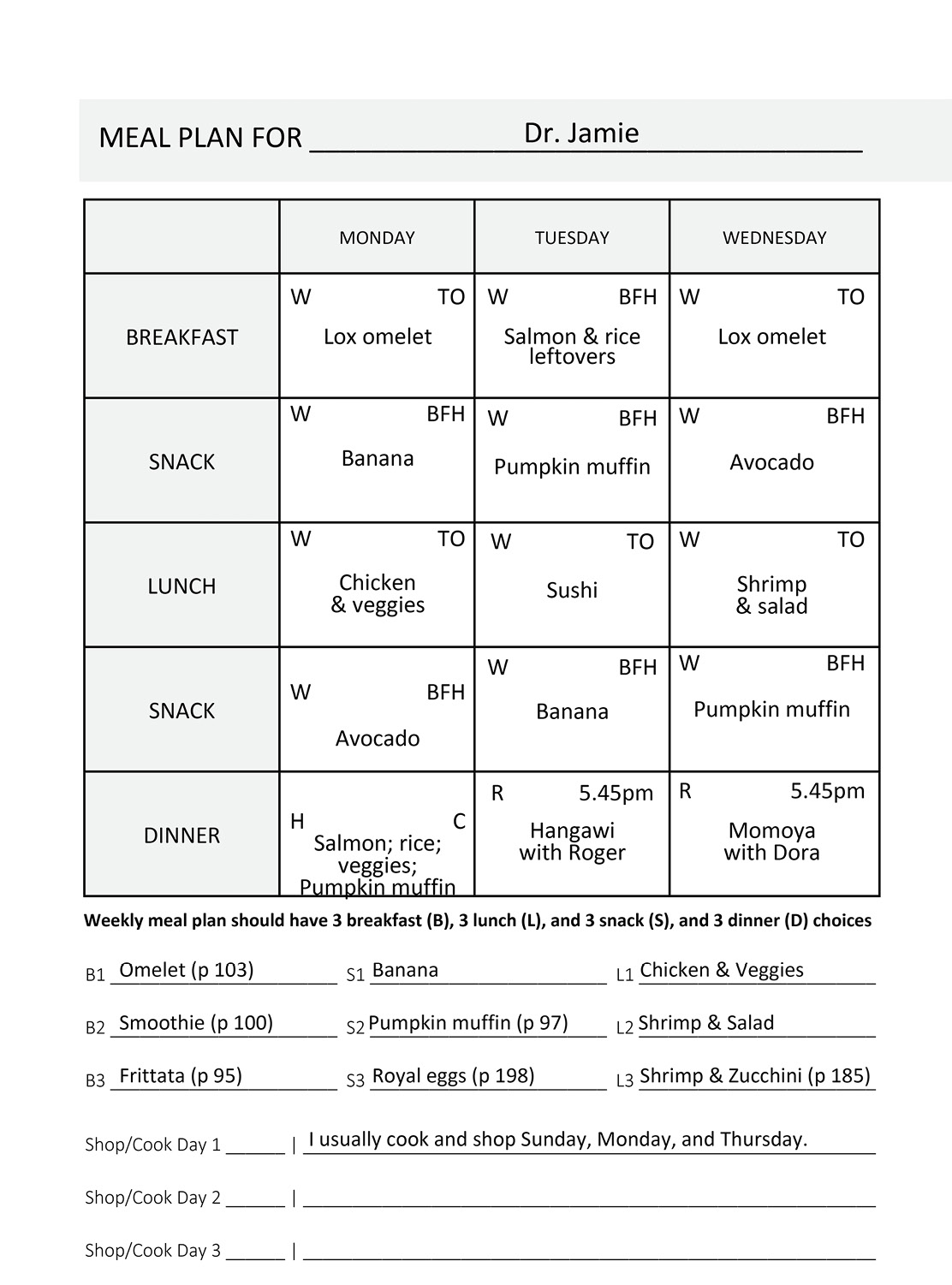

In order to achieve and continue maintenance, you must have a plan. You should have a variety of go-to meals. You should have at least three breakfasts that can be ordered from a restaurant and three breakfasts that can be made at home. Depending upon your work, you may have to bring lunch and daytime snacks with you. Figure out which lunch options work best for you and then make sure that you have a cooler and/or refrigerator to store your food. You will need proper food containers for transporting food. I double-bag; I have found self-closing plastic bags to be excellent for most foods, especially when smaller bags are placed within a one-gallon bag to prevent spillage.

You will have to cook, or at the very least prepare, some food. Options that work on-the-go include hard-boiled eggs, turkey burgers, chicken breasts, rice, fruit, smoothies, and salads. Make a list of all the snacks you like that fit within the reflux guidelines.

Pick your days for shopping and food preparation. I recommend that you have a standard cooking time set aside twice a week, plus at least one on the weekend. Personally, I shoot for Thursday and Monday evenings when I can cook at my leisure. Create a shopping list on your computer that’s easy to handle as a checklist. It is going to be important for you to keep staples that you like in your kitchen.

Part of maintenance is planning so that you have enough to eat. That said, every meal need not be a delight. On those days when I am faced with a demanding schedule, two hard-boiled eggs suffice for breakfast, a banana is the morning snack, and leftover soup or fish and rice are my lunch.

Learn to eat new things. Many of the recipes contained in this book are easily transported and can be used for additional meals during the week.

Planning, Cooking, and Meal Plans

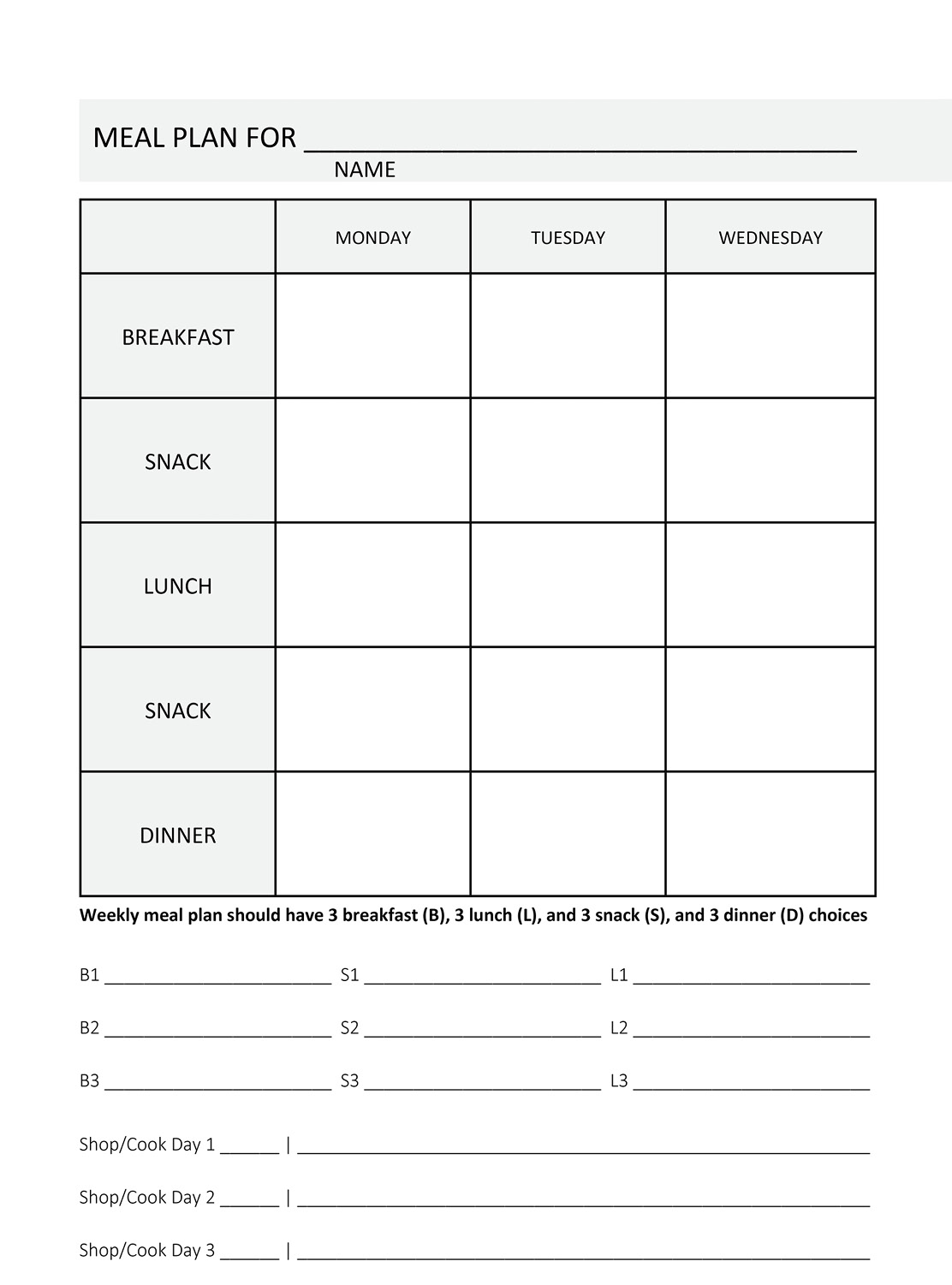

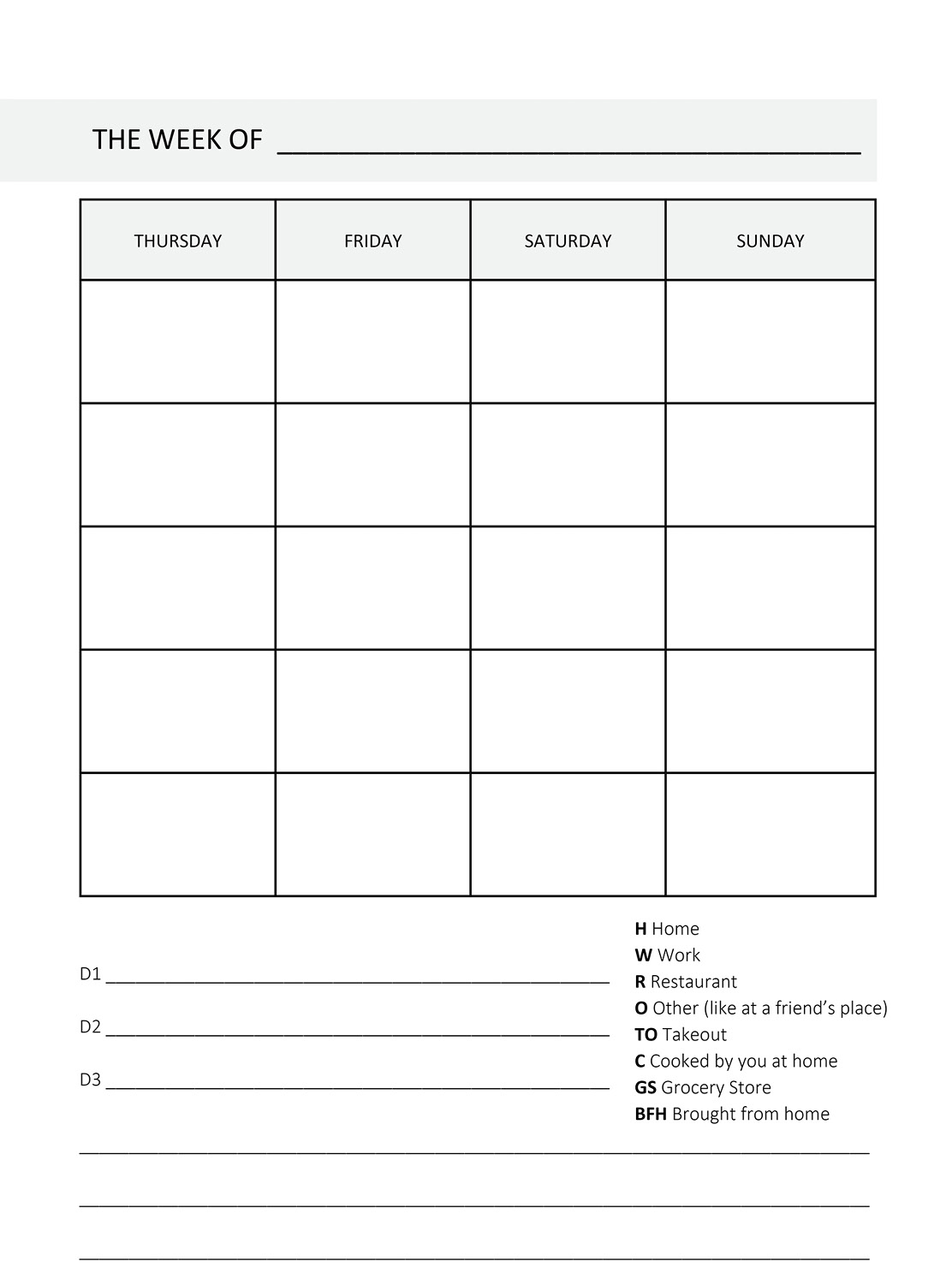

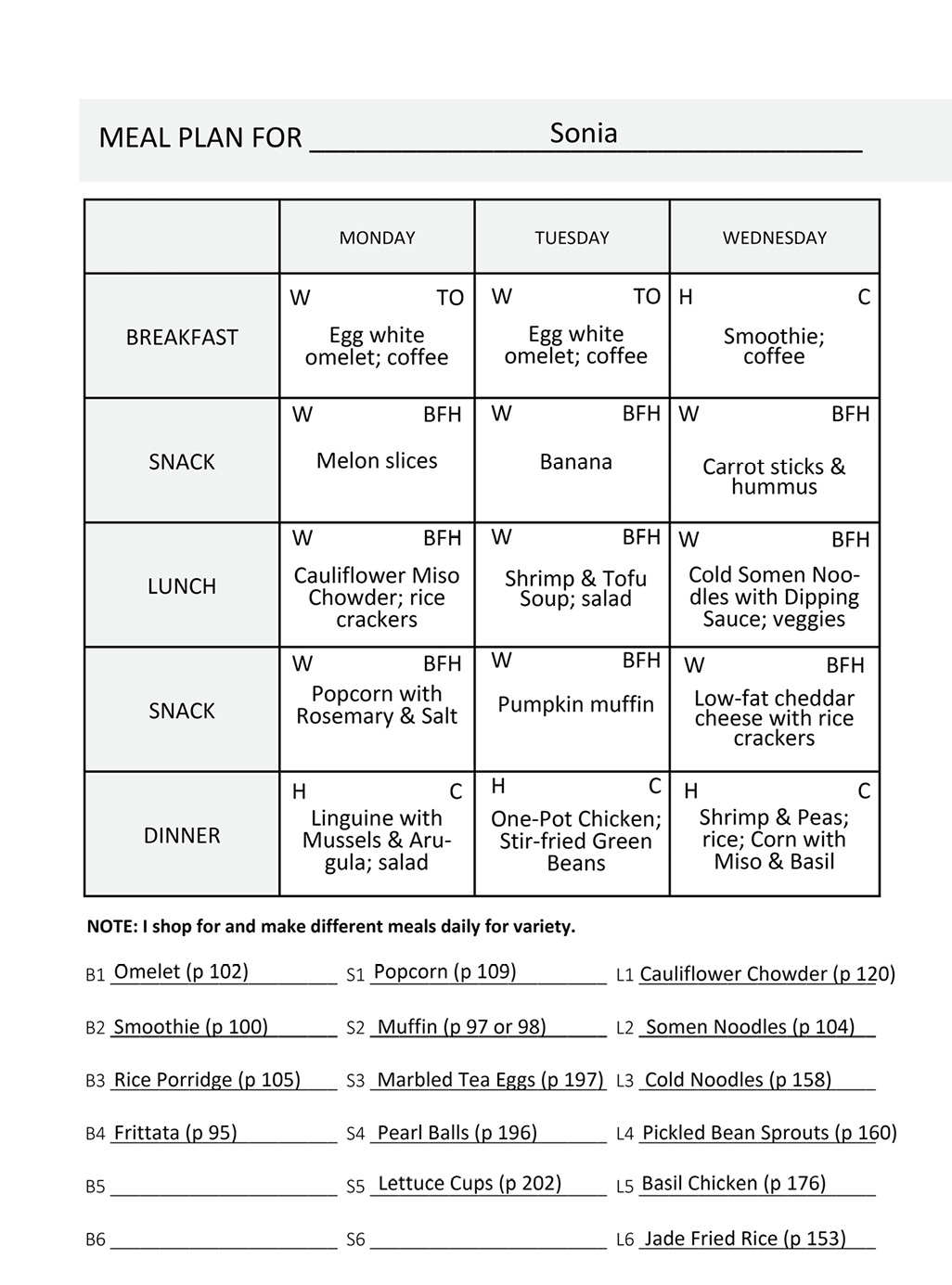

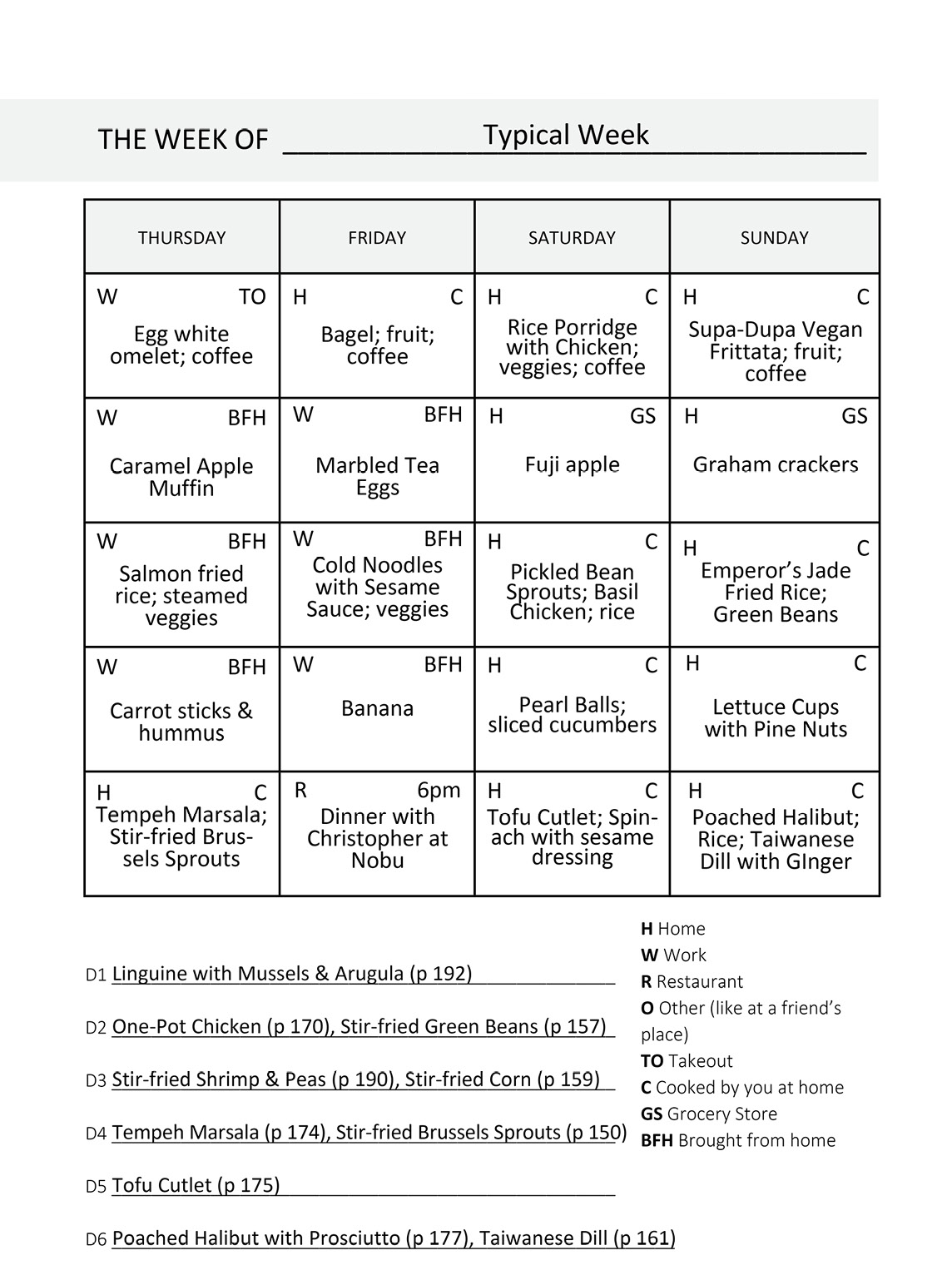

On the pages that follow, you will find the one-week meal plan template and three meal plans. Using the template to create your own meal plan is best. Try not to eat the same foods week after week. You should modify your diet periodically based on new discoveries, especially new recipes and new foods.

I discovered that I love the Roasted Cauliflower & Watercress Miso Chowder (page 120) for dinner and cold the next day for lunch. I also love the Gluten-Free Pumpkin Muffins (page 97), both in the morning for breakfast and as a sweet snack or dessert.

Planning and cooking are necessary if you are going to keep to Dr. Koufman’s Acid Reflux Diet. Think discipline and structure, but think fun and adventure as well. Creation of a meal plan a week ahead is—well—basic planning.

Before you start, there are several key variables: home-cooked vs. store-bought, and home or workplace eating vs. dining out. Store-bought means takeout from a restaurant, bodega, or grocery store. So you can cook it or have it cooked for you, and you can eat it at home or away from home.

To get the best results, you should make your own meal plan; the process of planning what you will do for the week ahead is key.

Now, each day, I recommend that you have three meals and two snacks, so to cover the workweek (Monday through Friday) plus the weekend (Saturday and Sunday), you will have to fill in 35 boxes.

Here is the sequence that I recommend to fill out your meal plan for the week:

- Fill in all eating-out dates and restaurants first. This includes breakfast, lunch, and dinner engagements, even coffee or “high tea.”

- Decide which days you will cook (designated “Cooking Days”) and prepare food and/or shop. Obviously, you can shop another day in advance if you like.

- Before you fill out the meal plan, fill out the B, S, L, D lines: B1, B2, B3 are three breakfasts; L1, L2, L3 are three lunches; D1, D2, D3 are three dinners; and S1, S2, S3 are three snacks. You can write in more, for example, B4, S4, L4, etc.

- With each, determine where it will come from: BFH (brought from home), TO (takeout), etc.

- Create a shopping list for the foods that you will need for cooking, as well as other brought-from-home items such as alkaline water, fruits, etc.

- Fill out the 14 snacks for the week first, and remember that if you need food at work, you are going to have to bring it. If you have a refrigerator at work, that’s great; if not, you will need a good-quality cooler.

- Finally, fill out the entire meal-plan grid, and then check to see if your shopping list matches your food requirements.

On the pages that follow, you will find the one-week meal plan template and three sample meal plans, one by each author. They are provided to demonstrate the different ways people eat. My meal plan is pretty close to

the detox diet. Sonia and Chef Philip cook most of their own meals.

Dining Out

Depending upon your stage of the reflux diet, you will have different degrees of freedom when dining out. If you are on the two-week reflux detox diet, you will have to go to a restaurant that serves grilled, baked, or broiled fish or chicken, a salad with no dressing, and grilled vegetables. There is no butter, cheese, or sauce during detox.

During the transition, maintenance, and longevity phases, planning is still necessary, but it gets easier as you gain experience and health. In general, ethnic restaurants (e.g., Mexican, Italian, Chinese) make it harder, but not impossible, to maintain your reflux diet.

If you are on a really limited diet, you’re going to have to think about where to eat out and what you can order before you go. Most restaurants have their menus online, so it is easy to see your options, even if you’ve never eaten there before. This awareness means communicating with friends, relatives, and business associates before dinner reservations are made. Tell your fellow diners in advance, “I am on a restricted diet, and I would prefer it if we could dine at a ____ restaurant (fill in the blank), and how about a 6:00 p.m. reservation?”

Furthermore, if you are on an especially restricted diet—gluten-free and dairy-free, for example—you have to negotiate with your server when ordering. You must specify that you do not eat butter, cheese, bread, or pasta (unless it is gluten-free), and you must ask how the fish/chicken/beef is prepared.

In an Italian restaurant, the grilled octopus and the branzino (sometimes listed on the menu as Mediterranean sea bass), prepared in olive oil (not corn oil or butter), are excellent menu choices.

I am gluten-free, dairy-free, and sugar-free, and one of my favorite restaurants in New York is a well-known French restaurant. On my first visit, I explained my diet. I was surprised when the response was, “No problem . . . no problem, except for desserts.” They would bring me an appetizer and sympathetically announce, “Instead of crème fraîche on your shrimp, there is a confit of melons.” As time passed, I became friendly with the servers and the chef so that when I went to the restaurant, the server would ask with a smile, “So, Doctor Koufman, are you still not eating desserts?” That was their code to let me know that they still understood the limitations of my diet and could still accommodate them.

It makes sense to begin creating consensus and familiarity among friends and co-workers, chefs and restaurants, about how you eat. It gets easier over time.

The key variables to successful restaurant dining are the front-end negotiations with your dining companions and with the restaurant staff. If you are shy and think special orders can be disruptive, consider that, today, almost half of people dining in restaurants have some kind of special order. Things have changed, and servers and restaurants are now used to accommodating “fussy” eaters. Get to know the staff, and you will find better choices, food, and service. And the upside is that you will establish a repertoire of suitable, maybe even terrific, restaurants that know you and will cater to you.

It is also important to keep people accountable. If you are gluten-free, for example, and you get sick after dining in a restaurant, call the restaurant and complain. Think of yourself as a consumer who cares about what you are consuming. If you took your car to a car wash and it was still dirty afterward, wouldn’t you say something? If you are a good consumer, act like one, especially when it comes to your food.

Again comes the question of what to drink. Water, coffee, and iced tea are your best basic choices. A discussion of alcohol as a trigger food can be found on page 58.

Now we return to the tricky part. Almost everything we have discussed so far might not rigidly apply to you. If you are in the maintenance and longevity phases of the diet, you are no longer really a refluxer, are you? You are in remission. So, the question becomes, how much can you cheat, and is it really cheating? Yes, you should probably continue to avoid your big trigger foods, as well as all bottled and canned beverages excluding water. However, “reflux-unfriendly” foods may be fine on occasion. As you will see in the recipe section, we sometimes use wine and vinegar and sesame oil, all potential trigger foods for some people, but not for most. This is one of the areas of reflux management that you must do for yourself—that is, identify your trigger foods (see page 53).

When you are healthy, you do not need to color within the lines all the time. The basics don’t change, but the details can. The key is to know your limits and avoid making unnecessary and costly mistakes. As you change how you eat and plan your meals, you will also change how you think about food. As you mature as a healthy eater, you will find that dining out is pleasurable and easy despite the fact that you order with care.